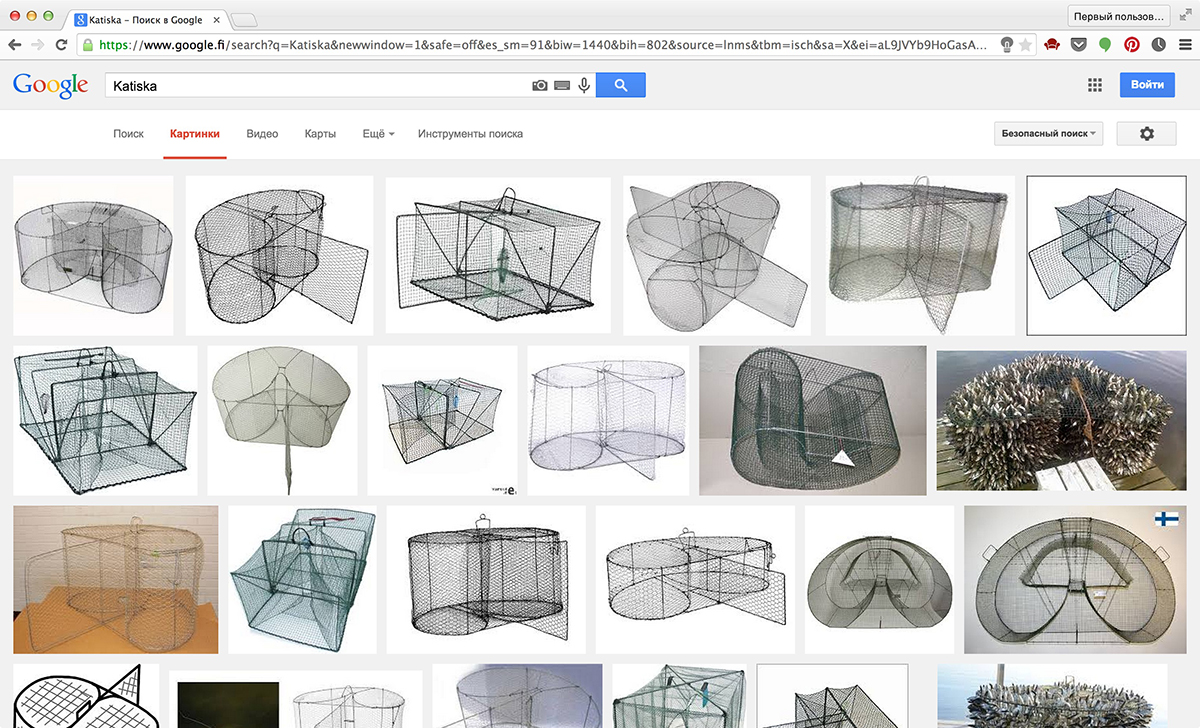

During the visit I was paying particular attention to the comments of the city planning officers that came out between the slides. At one point, the course of the talk drifted towards the fish catching practices that were popular in Pori. One of them was connected with the so called fish traps (Katiska in Finnish). To illustrate this word, one of the officers opened a google image search for Katiska.

My first urge was to create a big version of a native-american dream catcher and place it near the river.

On a very basic level, Dream Catchers symbolise protection and were originally created to drive away evil spirits from a newborn baby’s cradle. Additionally, some people believe it its ability to save good dreams and filter out bad ones. In relation to the Kokemäenjoki river, I saw a dream catcher as a reminder about the properties of the river beyond its physical characteristics: feeling of the constant flow, invisible life inside and a changing character.

In a fast changing and technologically advanced city of today one hardly notices all the subtle events that happen in the river. Yet it’s a perfect analogy of a life — a chain of random and fast changing moments that are lost forever the second after they appear.

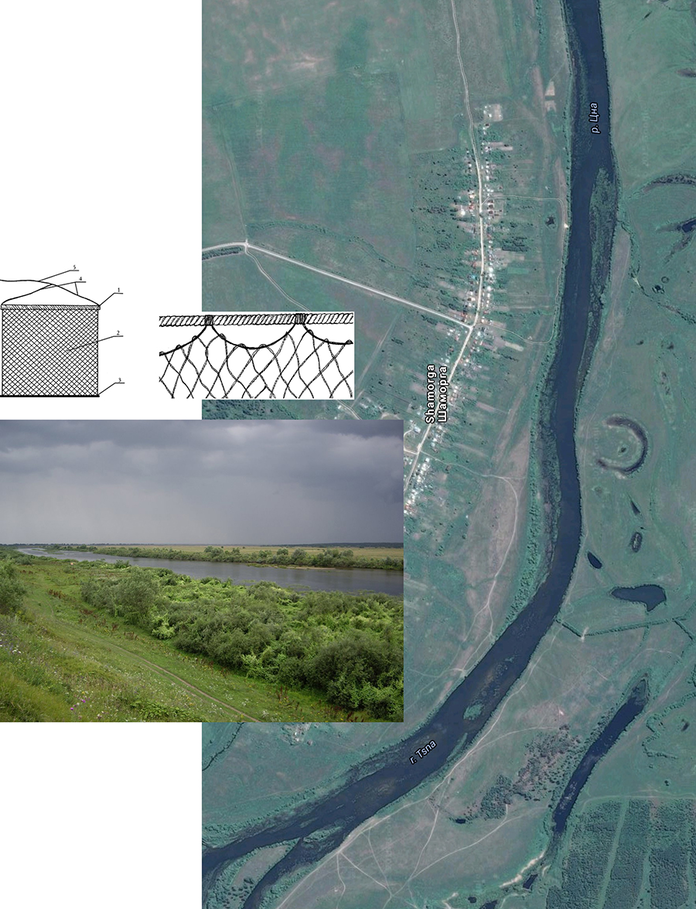

Most of my memories connected with fishing come from my early teens, when I was spending Summer in a small village in the southern part of Russia, a home to my father’s ancestors. It is a very authentic village located on the shore of the river Tzna, with its original look and feel still in the air apart from rare cars and electricity pols. During my time there I used to go fishing together with a woman who lived nearby and taught me the basics of this craft. Instead of the road, we used the so called “televisor” — a device consisting of a net and floating elements on top that prevented it from drowning. The “televisors” were usually installed in the river in the late evening and collected early in the morning, with the fish trapped in the nets.

During our exploration of the Kokemäenjoki river I was looking at its character and specific features that contribute to it. One of the most interesting observations from our walks was how fast the river changes from an “official” landscape — with embankments, bridges and elevated shoreline to “wild” and private one, full of natural details.

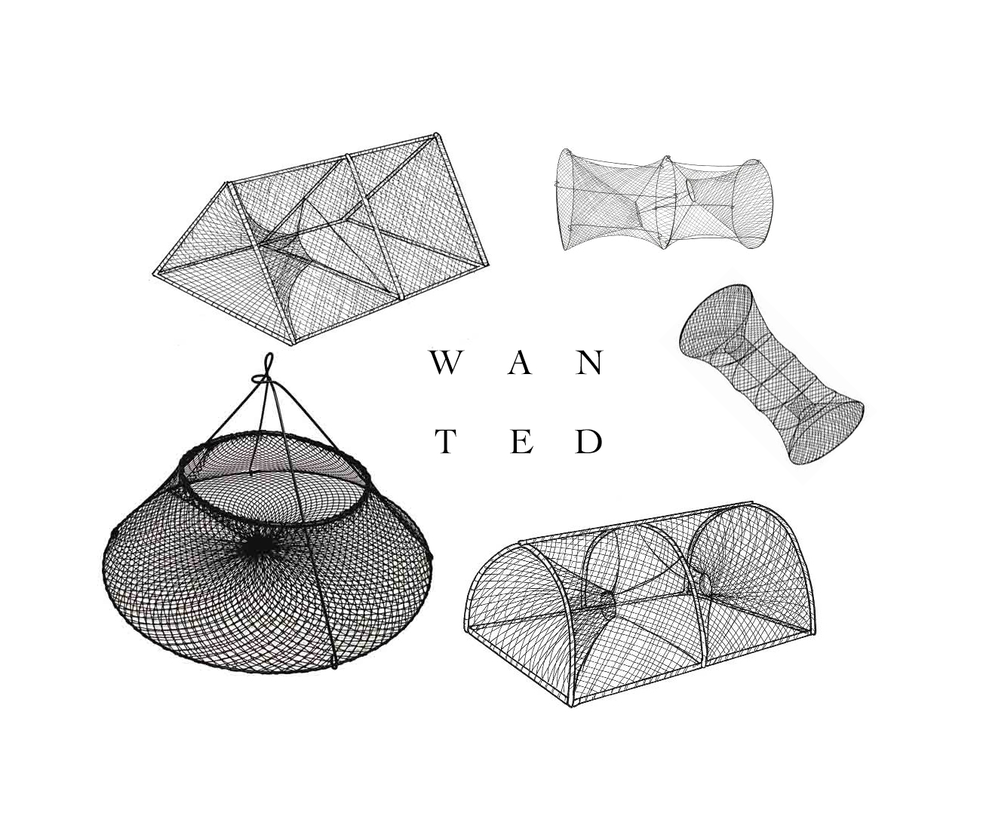

The resulting array of images displayed beautiful metal structures of different shapes and sizes. They looked as though specially designed as art objects and I decided to incorporate one or several of them into the dream catcher. On one hand, that would allow me to establish associations with the fish, and on the other hand, distance from the direct copying of the native-american artefact. On this stage I could create a first sketch of the artefact and embed it into the landscape.

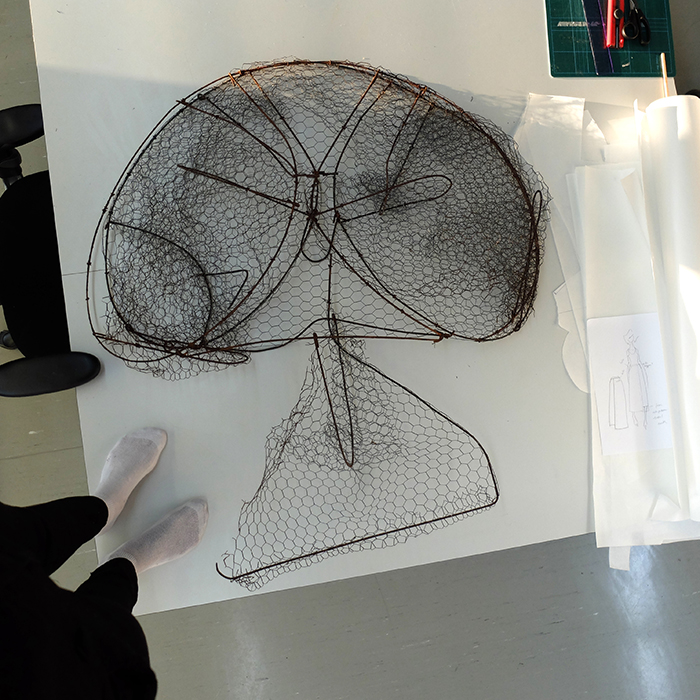

One of the most difficult part of the project was to find an old fish trap that could be used for the installation. Despite the expectations, a search in online shops and a request in social networks didn’t produce any results. Fortunately, one of the professors at the Department of Design heard about my search and told that her family has an old fish trap. She was happy to give it to me since the trap wasn’t in use for a long time and occupied a lot of space. Her fish trap was indeed large in size and had a hole in it from a bird that was stuck inside and was eventually saved by sacrificing the trap.

This practice was accompanied by lots of memorable experiences: the smell of the fish and the river, sunrises early in the morning, calm and almost mirror-like water, the process of untangling the wet nets after the fish was taken out. The river fish was full of small bones, and it was a bit dangerous and therefore slow to eat. So if the fishing process wasn’t about the food, than what made it special? In my case, the possibility to interact with the river and the person who taught me new skills and passed to me her embodied knowledge. I haven’t been in this village since I was 14 years old and I’m not sure if I ever have a chance to come back. The river has probably changed: the weeds might have overtaken it, and it will hardly be the same as in my memories.

The shrinking boundary between a person and the river made the experience of walking along it very private and intimate. However, it didn’t seem that other people share my excitement with this change: Pori citizens were not drawn to the river, but rather passing by it in pursue of other activities. My intention therefore was to create a setting that would emphasise the river as something that can be appreciated, observed and enjoyed in its “wild” character.

The message that I wanted to create was about noticing and appreciating the constant subtle changes that happen in the river that are gone and lost unless someone catches and remembers them.

In order to use the trap as a part of the artefact, it first had to be cleaned and flattened. Because of the weight of the trap and its large size, I could not follow my original plan to hand it below the main circle of the dreamcatcher, but had instead to use the trap as the central element. This compromise had an upside: the silhouette of the trap reminded a stingray or a jelly fish and was easily associated with water. To finalise the object, I added the net and some stylised feathers, and chose a bright orange colour to make it appear brighter among the trees.