For Finnish: NOKKAKOLARI – TAIDE JA TUTKIMUS KOHTAAVAT

10th version1

TEEMU MÄKI

QUESTIONS

What is research, what is knowledge, and does the former only aim at producing the latter? Why are (some) artists trying to combine art and research? What can be gained by it? What are its possible dangers or failures? What is it needed for? What is ‘artistic knowledge’ or ‘art's own knowledge’? What is included in it, what separates it from so-called scientific knowledge? In what sense is art research? How and to what extent should art and research be combined in the university context?

WHAT IS THIS TEXT FOR AND WHAT IS ITS PERSPECTIVE AND CONTEXT?

This is a text, an exposition written by an artist. It’s about art’s relationship with knowledge and about the nature of artistic research. Even though I often write in a very general, nonpersonal manner – for example, about definitions of knowledge and research – my perspective is all the time that of an artist. Also, my goal is that of an artist, because I’m looking for the kind of definitions and uses of knowledge that would help artists and artistic researchers in their work – be that work art making or non-artistic building of theory.

At the beginning of the text I contemplate what would be reasonable definitions for knowledge and research in the context of art and research. After that I make a list of what the most common motivations are – according to my own experience in the arts and in academia – that tempt artists to combine research with their artistic practice. Then I write about artistic knowledge and suggest that it could be divided into four subcategories. In the following chapter I attempt to justify art as a good form of research and explain why I see art as a special form of philosophy and politics. In the chapter ‘Not Only for Knowledge’ I deal with how artistic research differs from other types of research and what its special features are. Then I return to a more inventory-like writing and make a list of five categories, within which I think the various traditions of combining art with research can be grouped. In the ‘Conclusions’ chapter I sum up what the facts and views I’ve presented in the text might mean if applied to the university system. All in all the dramaturgy of my text, my monologue, is that the amount of artistic matter (images, sounds, poetry, etc.) increases during the presentation – and that the whole blabber finally even ends with a poem. I hope that this form embodies the deliciously schizophrenic position of an artist who jumps like a bunny rabbit back and forth between ‘pure research’ and ‘impure art’, and whose heart in the end belongs to the art side of that gap.

Some may find the tone of my text inappropriate, because a rather objective and value-neutral tone alternates with an openly prescriptive and opinionated one. This, however is precisely the way I wanted to write, because if I have anything special to say about the relationship of art and research, that specialness arises from my own personal perspective and experience as an artist.

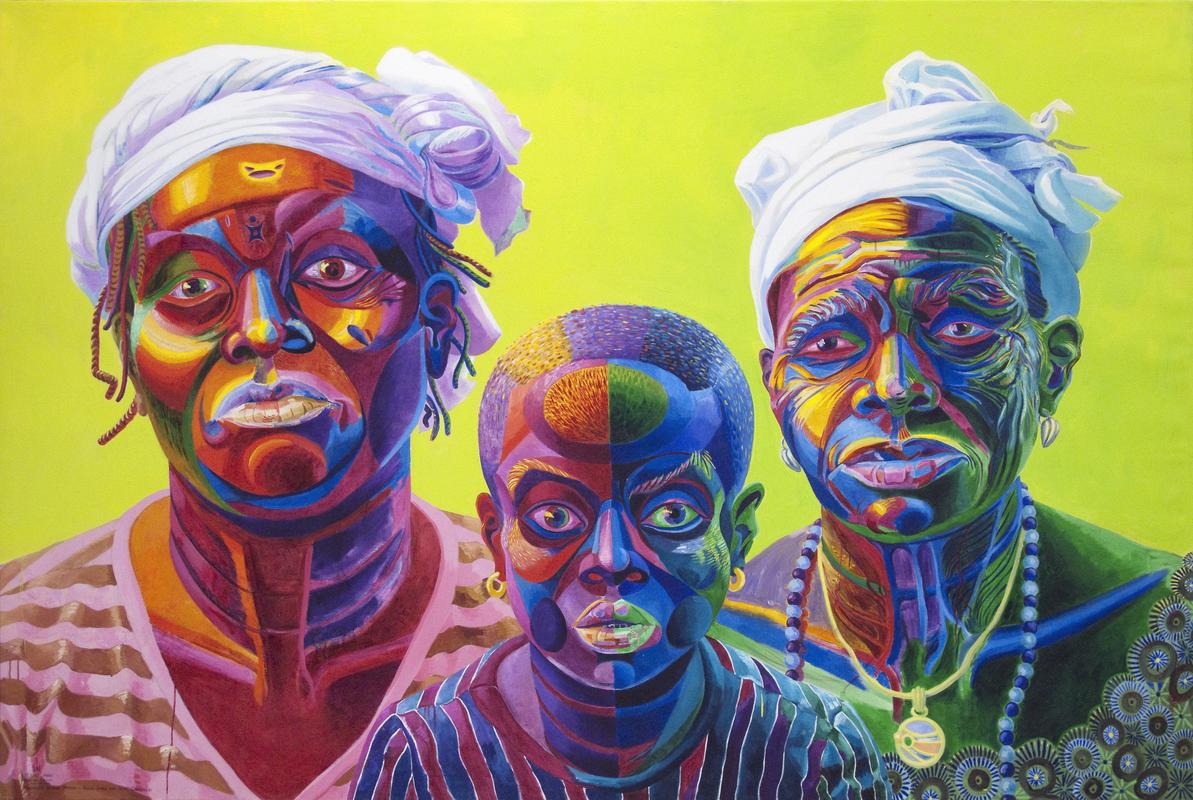

As my artistic research is so organically glued onto and a part of my artistic work, the presentation – especially the latter part of it – also contains many samples of my art. Some may think that this is embarrassingly egocentric and wrong, that one should not write about the definitions of art, knowledge, research, and artistic research on a general level if one uses the deeply personal – that is, the author’s own art – as examples. In my defence I want to note that I don’t claim that my artworks are in any way ‘exemplary’. And I don’t even claim that they are especially apt, effective, and informative as examples of the genres of artistic research that I write about. Despite that I use my art as a source of samples, because I want to show the roots of my text, in order to make my text more understandable. And, as I am an artist, the roots of my research are always in my art. My art forms the perspective and context from which my research texts grow. The biggest challenge of artistic research in my opinion is how to deal with the gap that separates artistic experience from verbalised theory. No bridge can be built to connect them, but some kinds of jump and intercourse are possible. Attaching my artworks to this presentation is an attempt to continue and share this intercourse. If readers find the artwork samples unhelpful, they should just skip them and focus on the text.

I’ve avoided specialist vocabulary and striven for language that would be easy to read for anyone, anyone who happens to be curious about the intersections of knowledge, art, and research. There are three reasons for this. First, I’m not one of those thinkers (maybe not a thinker in general) that say that philosophy and other modes of theory building primarily concern creating new concepts or new uses for old concepts. I’m one of those who try to use plainspeak, who try to say something new with the familiar, to change the world, instead of mainly trying to expand the vocabulary and arsenal of concepts of those who speak about the world. Second, artistic research is such a marginal field that I don’t think it should weirdify itself any further by concentrating on internal discussion with the sect’s own language. And third, as I can, in my art, use a specialised, ambiguous, and dissonant language, in my straightforward research texts I’d rather go after the opposite.

I’ve written this text for myself, to clarify the various types of knowledge and their meaning to me as an artist and as a consumer of art – and now my intention is to share my thoughts about it with others. I’ve had many people test-read this text and due to their comments I have had to lengthen the text quite a lot. Test readers have been my colleagues or my doctoral students or my master’s degree students and some of them know very little about art. I’ve tried to take into account all the feedback, to make this exposition as understandable and enjoyable to all as possible.

I don’t name many sources or use many references. Some may think that this pulls the rug from under my feet, but I hope not. The categorisations I propose are mostly my own and completely voluntary, I do not claim they are the only ones possible. When, for example, I divide ‘artistic knowledge’ into four categories, I use the categorisation I created in my doctoral dissertation and point out that it’s just one possibility. I don’t have time and space here to go through the many other categorisations launched by others.

Some readers my wonder why I attach so many artworks in this exposition and yet write so little about them. The reason is that I tried to write a text that would be meaningful without any image, poem, or sound attachments. And on the other hand a text whose ideas the reader could immediately test with the attached artwork samples. The testing itself I have mostly left to the reader, in preference to telling how each attached artwork, in my opinion, is connected to and testifies in favour of what my argument in the text is.

THE DEFINITIONS OF RESEARCH AND KNOWLEDGE

There is no single universally agreed definition of research and knowledge, not even in the university world, apart from their mutual link, perhaps, which claims that ‘research is the (organised) search for knowledge’.

What, then, can be said about knowledge? For example, knowledge is the theoretical or practical understanding of something. It does not have to be verbalised or verbalisable or even conscious: skills and silent knowledge are knowledge as well.

If we stretch the definition of knowledge to such an extent, what separates knowledge from superstition and random beliefs? What is the understanding mentioned above and how can it be measured? I propose the following:

We can detect knowledge by its usefulness: it is mental or physical understanding or a skill that makes us better able to do something, use something, or predict the future activity of something. So, the old saying, ‘the proof of the pudding is in the eating’,2 can be pragmatically applied here as well. Any systematic procedure that either (A) increases empirical, logical, or other type of verbalisable knowledge or (B) improves our performance in the function in which we try to excel can be defined as research. And as the research procedure and knowledge obtained through it can be nonverbal and even subconscious, we cannot always detect or test how systematic the research method is; we just have to look at the research results and conclude that if they work in the intended manner, the process with which they have been achieved must have been systematic, not random or failing.

For most people, this pragmatic view is probably relatively easy to accept. It only becomes problematic in the contexts of science and the university, where the validity of research methods, the verifiability or falsifiability of research results, and the reliable shareability of knowledge are of utmost importance. Moreover, in both these contexts, gatekeeping is an important function that prevents charlatans and incompetent people from gaining undeserved respect and doing actual harm. This is mainly a good and understandable thing, since I need to be able to trust a surgeon already before s/he slices my belly like a pudding.

However, in the philosophy of science, definitions of research and knowledge have become more and more pluralistic: various, strongly contrasted definitions are simultaneously in use, and although there is competition, friction, and even conflict between them, science is not collapsing. The versatility of the new definitions of research and knowledge are a bigger challenge to the university system than to the scientific community or anyone else. On the one hand, universities do realise that there is a need for definitions of research and knowledge that are more versatile and flexible, but on the other, they find it difficult to create quality control systems that reliably tackle things such as silent knowledge or artistic research (I will define that peculiar term artistic research a bit later). For universities, gatekeeping is such an important function that they may be stuck with rigid and narrow definitions and practices that hinder education and research.

Perhaps a proof of this is the critical feedback my university received when it recently carried out a Research Assessment Exercise to find out what kind of research is done in the university and how successful it is. In their final report, the assessment panel complained about the narrowness of the definition of research used in University of Art and Design Helsinki (now a part of Aalto University):

The definition of research was too narrow. It did not take into account the significant contribution that practice based work and ‘artistic’ work in art and design makes to the academic research culture. The current instrument of measurement, based on ‘scientific’ achievement (i.e. traditional published materials) does not adequately reflect or monitor the processes and outcomes of ‘artistic’ practice endemic to the staff’s work.

As a result of this, many Units have self-censored much of their own sometimes excellent work. If the new university wishes to include art and design in its international agenda it will need to address the more modern international paradigms, as already practiced in other European countries.3

The word ‘research’ is used [by the assessment panel] to cover a wide variety of activities, with the context often related to a field of study; the term is used here to represent a careful study or investigation based on a systematic understanding and critical awareness of knowledge. The word is used in an inclusive way to accommodate the range of activities that support original and innovative work in the whole range of academic, professional and technological fields, including the humanities, and traditional, performing, and other creative arts. It is not used in any limited or restricted sense, or relating solely to a traditional 'scientific method'.4

The views of the research assessment panel come as no surprise to professionals of artistic research, but I quote it nonetheless here, because to the vast majority of the world and university world it is weird. In the field of artistic research it is common to frown at the ‘infidels’, who are not familiar with the field, and at their ‘backward’ thoughts. However, I think it would be better to acknowledge that most people consider art and research to be polar opposites and that only very few universities have the door open to other points of view on this. After the acknowledgement of facts one can then try to change things by speaking in a language that the opponent understands.

WHY ARE (SOME) ARTISTS TRYING TO COMBINE ART AND RESEARCH?

Adopting new, flexible definitions of research and knowledge can be difficult for the university system. It is in part because of this that the university is often an uncomfortable or even hostile environment for artists who are willing to embark on doctoral studies or post-doctoral research. It is also true that, in general, the art world does not care whether an artist has academic degrees or not – it is normal to think that academic efforts are things that some artists do instead of and at the expense of their art, not as part of it or to improve it. So, what is the point, then, for an artist? Why are (some) artists trying to combine art and research?

1.

To make better art. ‘Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) was okay, but he would have been much better if he had known more about art theory and the world outside his studio, too.’ Better artworks can perhaps be made, if:

- Artists become more conscious of their motivations and methods and of the impact of their art on audiences.

- Artists develop their practice in a more rational, orderly, and informed way.

- Artists gain greater knowledge of the non-artistic aspect of their themes and subject matter. Portrait painters or filmmakers interested in psychological insights gain much when they are educated in that field beyond what is taught in high school. Artists especially interested in global politics can make better art if they actually study economic theories instead of just scrolling through the Wikipedia articles on Karl Marx (1818–83) and Milton Friedman (1912–2006).

- Artists extend the potential subject matter of their art by acquiring new theoretical knowledge. This happens in two ways. First, becoming aware of theories previously unknown is like extending one's capability of hearing or seeing – the reality expands and becomes more perceivable. Second, theories are not just tools for the observation, evaluation, and modification of hard facts and reality, since theories themselves are also a significant part of our reality and existence. Theoretical knowledge is not just a way of seeing more and hearing better but also a part of the substance that we try to detect, understand, mould, and enjoy. Our existence, our lifeworld, is a totality in which the physical reality and hard facts mix with our poetic or rational interpretations of them and with visions of that which could or should be. Theories enrich and expand our lifeworld as much as modifications and extensions of the physical reality: we often experience theories intellectually and emotionally with the same intensity with which we experience external and physical reality. Thus, theories are an important part of our lifeworld even when they remain mere theories, without practical usage. Both of these ways lead to enrichment. Thanks to theory, we are able to see better, but theory in itself is also worth looking at. Thus, through theory we find and create new things to see and think about as well as things from which we can extract emotional experiences and make art.

2.

To understand and enjoy art more. ‘It feels good to watch Andrei Tarkovsky's (1932–1986) The Mirror (Zerkalo, 1974) again and again, but I'm unable to verbalise why. I want to learn to analyse it and dissect it verbally, to understand more, to open aspects of it that have thus far remained closed to me. I not only want to understand why I feel like this, I also, and especially, want to feel more, more variety, greater intensity.’

Two goals: to become more conscious (i.e., to understand more) and to get more pleasure (from art). Good theoretical knowledge and other modes of verbalised inquiry enable us to derive greater meaning and nourishment from a piece of art. This seemingly obvious notion must be repeated again and again, since many people – both in audiences and among art professionals – still mistake theory for some kind of antidote to art experience, as if an artwork was a crossword puzzle that can be solved with theory and thus made useless.

3.

To explain art better. ‘I can paint and I know a good painting when I see one, now I want to learn to verbalise my conviction.’

This is a narrow version of the previous motivation. Artists focusing on this do not strive after richer insights into art or more ravishing art experiences (or they don't believe that theory/research would yield these), they are just after better communication abilities. Their convictions are already cemented by intuition and emotion, and they no longer want to question them. Instead, they want only to construct a verbalised, rational justification for their beliefs and to be able to convincingly communicate them to others.

It is a mode that often produces no new knowledge about art, and also a mode in which it is rare that an artist's personal view and artistic practice develop further during the research process.

This mode clearly lacks the self-critical awareness that is an essential part of any serious study. Yet, we do not have to see it as a mere travesty of serious research; the lack of a self-critical ability is not necessarily fatal, as it does not automatically prevent an artist/researcher from producing shareable knowledge about how the disciples of a particular artistic style, genre, school, practice, or philosophy see and think. It just prevents the artist/researcher from evaluating the premises, the core assumptions of that school of thought, and from critically testing them with the arguments of its rivals.

Artists who don't want to question their beliefs seriously, but just want to learn to verbalise their convictions in a way that sounds rational, fail as critical researchers but can nevertheless produce useful knowledge. Often this knowledge is mainly of a pedagogical or social value. For example, just verbalising some of the core principles, practices, and goals of each genre can relatively easily expand the circle of those who are able to enjoy contemporary dance or free jazz or performance art. These core ideas and practices are often so obvious for practitioners and avid fans of a genre that they do not feel any need to articulate them verbally or theorise about them. For outsiders, however, the verbalised knowledge of the genre may be the essential key without which the whole genre remains off-putting, incomprehensible, and suspicious.

4.

To understand more of the world through art and then to change it with art. In a way, this is, of course, a variation or part of the motivation I listed first; the one in which an artist tries to combine art and research to make better art. Yet, the mode and goal of this more politically oriented motivation is perhaps distinct enough to be listed separately. The first motivation on my list was based on the idea that knowledge in general is helpful for an artist, too, while the fourth is based more on the idea that knowledge of the world is essential for artists if they want to tackle political issues. As Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956, or perhaps actually Leon Trotsky, 1879–1940) said: "Art is not a mirror that reflects the reality but a hammer which shapes it.”5 If we see art in this way, mainly as a philosophical-political activity, then gaining greater knowledge of the world becomes as important for an artist as gaining greater knowledge of art. To hammer the world into a better shape one has to know where to hit and why.

5.

To gain respect and better pay: ‘I'm good but I want to have some academic proof of it, too.’ This motivation is not good for art, research, science, or understanding.

–

Some form of research process is part of practically all art making. Most artists are not satisfied with merely absorbing the knowledge that is already out there, but also want to test it, modify it, connect it with their art making, and produce new knowledge, new values, and new experiences through artworks. On the other hand, the five reasons for combining art and research mentioned above do not automatically lead to research in the sense that the word ‘research’ is used in science and universities. If research is a natural part of practically all artistic processes, when is it reasonable to give it a special mention and talk about a ‘combination of art and research’ or about ‘artistic research’?

KNOWLEDGE OF WHAT? – THE FOUR CATEGORIES OF ARTISTIC KNOWLEDGE

All combinations of art and research use and strive for knowledge. Nevertheless, there are often other goals as well. Many artists focus mainly on the creation of new moral or aesthetic values or experiences; however, the hunt for knowledge is always a crucial part of the process, either as a tool or as an end in itself.

Non-artistic knowledge can be used, for example, to improve the practices of research of art or to develop artistic techniques. For centuries, psychological and sociological knowledge have been the sources of art historical and theoretical analyses of artworks. Moreover, advances in electronics have given birth to video art, or at least made video art possible, and they have since done the same for ever-new forms of media art. In these processes, imported non-artistic knowledge is not only used with artistic knowledge, it is also partially merged into artistic knowledge.

Artistic knowledge is knowledge about art or knowledge about something else produced by art or by researching art. In the introduction to my doctoral dissertation,6 I proposed that artistic knowledge could be divided into four categories in the following way:

1.

How to make art? – Knowledge about how art is made: knowledge of the process of the creative act, such as painting methods, composition systems, various traditions of how to train an actor and how to create a play for the theatre stage, and so on and so on.

When artists produce this type of knowledge, they often have a concrete need for developing better artistic methods: to make better artworks. Because of this, their focus naturally is different from the focus of those researchers who are not artists themselves. Both do mostly qualitative or interpretative research, but pure researchers usually strive for a more neutral, informative, and inventory-like knowledge than artists, who not only want to know how art is made but also take a stance on how art is made well.

2.

How to view art? – Knowledge about how art is interpreted, used, and consumed. How to view Kazimir Malevich's (1878–1935) Black Square (1913) and find it meaningful? How to read Samuel Beckett's (1906–89) Malone Dies (1951) as an especially rich form of existential philosophy?

Again, when artists are striving for this type of knowledge, their research interest is usually different from that of other scholars. The two opposing poles of research interests can be described as follows. One is mainly concerned with art history, such as in the family tree of artistic movements, and in creating an informative view of what happened in the arts and why. The other is more interested in how to get the most out of artworks, how to squeeze an artwork of all the potential knowledge and passion that it carries. I assume that artists are usually more interested in the latter – in the nourishing potential of artworks. Their research mode is more practice-led in this sense as well, as it aims to use art and to maximise the sensual and intellectual rewards of artworks rather than to explain art or maximise art historical knowledge.

3.

What did the artist mean? – Knowledge about the artist's conscious intentions and unconscious aspirations. What did the artist try to do, express, or achieve with the song, painting, or film s/he made?

An old-fashioned way of writing art history considered that knowledge of an artist's intentions was crucially important; thus, it misunderstood intentions, mistaking them for the actual content of the artworks or the ‘correct’ or best interpretation of the work. Today, the author is no longer thought to have that kind of authority, and therefore, unlike earlier, knowledge of the artist's intentions is not considered such a central key and guideline to the interpretation of artworks. Now all interpretations are allowed, and the artist's own suggested meaning is just one of them. Pragmatically, most of us think that the interpretation that yields the most interesting things from the artwork is the best one – no matter how close or distant it is to the artist's own intentions and the experiences s/he aimed at.

However, even though knowledge of the artist's intentions is less important to art historians and the audience than before, it can still be very useful to the artist. An artist researching his/her own intentions and the intentions of other artists has a special, practice-based approach and also a special, practice-led goal: to produce artistic knowledge that is useful for artists in art making.

The more that artists are aware of their intentions and motivations, the better enabled they are to question, adjust, and develop them, and the better enabled they are to achieve their goals, make the kind of art they want to produce, and achieve the desired impact on the audience. Also, comparing the intentions and end results of other artists is often extremely helpful for artists when they are trying to adjust their own working methods. For example, an artist may research how a colleague's finished work differs from that colleague's ideas concerning the form and content of the work before it was finished. Alternatively, s/he can study how the actual, proven impact on the audience differs from the one the colleague was after; but this comparison is, of course, only possible if knowledge of the artist's intentions is available – if artists share the ideas they have had while making the work at the studio.

The audience, of course, reads a work in a way that is different from what the artist intended. The artist has written a message that differs either a little or a lot from what the audience actually finds in the work and believes to be the artist's message. Knowledge of this discrepancy can be useful if and when an artist wants to become understood, but it does not mean that art is shrunk into mere communication of exact, locked, and unambiguous meanings, because only a part of an artwork's content and meaning can be translated into a commonsensical, verbalised argument – and artists are always only partially aware of their motivations and aspirations and of the content they have planted into their work. If we agree to use the word intention to describe a conscious effort towards a verbalisable goal, it is important to remember that only some of the motivations and goals of artistic practice fulfil these criteria. Moreover, a part of the unconscious can be migrated into the realm of the conscious (the intentional) through self-reflection, but only a part. Keeping this limitation in mind, artists may still want to become as aware as possible of their own aspirations, of the intentional and the verbalisable part of the content of their art, and may also want to know what the audience makes of that art in order to develop both the content and the form of their art further.

4.

Art's knowledge about society and humanity. Art uses special tools, methods and languages, and may thus produce knowledge and insights about society and us that would be hard or impossible to produce by other means and in other spheres. Art makes observations, analyses, and claims about the world; it tests and evaluates ways of living, it creates and proposes new values, new ways of living and experiencing. Art is thus constantly interfering and overlapping with and contributing to non-artistic knowledge.

Combining art and research means importing non-artistic knowledge into art, but this does not have to be a one-way street. Often, the process is reciprocal: non-artistic knowledge is imported into the research or the art making process in the field of art, after which the research results or artworks are shared, exported, and offered as knowledge or moral philosophical reasoning that can be useful or rewarding in some other sense, not just to the arts but to society in general.

The four categories of artistic knowledge are not clearly separable. For example, it is clear that art's knowledge of the society and humanity that surround it not only resides in the artworks but also in and throughout the interpretations of artworks and ways of experiencing them. The third category of artistic knowledge – knowledge about how art is interpreted, used, and consumed – can be fairly neutral knowledge about how to listen, how to look, how to read; but, on the other hand, it is with this interpretational toolbox that we open the artworks' philosophical-political content. The content of the toolbox can therefore have a crucially important influence on what we find and create and on what – through our art-related discussions – the social impact of our art experiences is. Thus, knowledge about how art is interpreted, used, and enjoyed is, in the end, rarely even close to neutral. It is a type of knowledge, in which it is almost impossible to stick to a merely descriptive and seemingly neutral verbal analysis of artworks. Indeed, an analysis cannot be done properly, at least not in the deeper sense of the word, without assessing the artwork's social, political, and philosophical meaningfulness and value. And when one of these aspects is taken into consideration, the argument is not anymore only about the artwork; instead, it expands into a philosophical-political argument about the world.

As we digest all art into a sort of nourishment through some kind of interpretational process inside us, we could think that we do not need the fourth (‘art's knowledge of society and humanity’) of the aforementioned categories at all and that three would be enough, because, in a way, the third category partly includes the fourth. However, I think that it is important to mention the fourth category separately, as it is the most important of all these categories. By mentioning it separately, I also want to point out clearly that art as such produces, contains, and spreads knowledge, including when it does not go through any academic machinery that produces theory-grounded explanations of it.

The fourth type of artistic knowledge stretches definitions of knowledge and research in a fruitful way. In artworks, knowledge of facts is mixed with knowledge of values. The mixture is ‘impure’ knowledge, and the research process that leads to it is ‘impure’ research in the sense that it does not pretend to be objective or impersonal. However, it is not random or solipsistically subjective either. Instead, it is just an attempt to create and use knowledge and values together. Its starting point is the idea that knowledge cannot be clinically separated from values or the perspective and context where it is created and used.

WHATEVER WORKS – THE JUSTIFICATION OF ART AS RESEARCH

Should the combination of art and research aim at creating knowledge about art or about the world through art? Should it produce more knowledge in general or more knowledge about art in particular, or should it focus on producing better artists and better artworks? Furthermore, should this type of research be neutral (descriptive) or should it openly demand change (prescriptive)? The list of open questions concerning the connection between making art and doing research goes on and on. In society and in the art scene, as well as in science and university circles, there is no consensus on what the combination of art and research should aim at.

In these discussions, the fourth type of artistic knowledge is often altogether forgotten, but for me, as an artist, it is the most important of all. I am more interested in the valuable insights that art or artistic research can produce about the world and in the kinds of changes it can cause in society than in what research of art can tell me about the family tree of artistic movements, the structure of artworks, or the way some of the players in the field manage to steer the art world according to their own agendas.

I hope the combination of art and research will lead to better artworks: works with a deeper understanding of the world and a more insightful commentary about how the world is and how it could and should be.

If we accept that art can produce knowledge about society or other philosophically or politically meaningful insights, then we must also, quite radically, accept art as a potentially valuable mode of research in general. We should be able to detect a significant research tendency in much of art, not just in the kind of scholarly writing or art making that labels itself as a combination of art and research.

Brecht's poem ‘Traveling in a Comfortable Car’ is an extremely simple yet illuminating example of art as research, an example of the attitude where an artist tries both to see the world as it really is and to change it:

Traveling in a comfortable car

Down a rainy road in the country

We saw a ragged fellow at nightfall

Signal to us for a ride, with a low bow.

We had a roof and we had room and we drove on

And we heard me say, in a grumpy voice: No,

we can’t take anyone with us.

We had gone on a long way, perhaps a day’s march

When suddenly I was shocked by this voice of mine

This behavior of mine and this

Whole world.7

It may not be normal to think of this poem as a combination of art and research, but if we assume that Brecht had first acquired social, political, statistical, and economic knowledge and on this basis built his philosophical-political statement in the form of this poem, then the process as a whole can surely be seen as research. Moreover, the theoretical component of the poem is evident not only in the preparatory stages of its writing – that is, in Brecht's investigation of what is going on in the society – it is present also in the lines, or between the lines, of the poem itself, as a self-critical analysis of how we tend to react to those in need. In other words, this little poem can be regarded as qualitative research and a critique of our habits of moral reasoning. Research can be totally embedded into artworks such as this; it does not always have to take the form of a theoretical text written by an artist to accompany or explain his or her artworks.

If we accept the art-as-research option and acknowledge that art making as such can be a form of research, this does not remove the constant need to feed artistic activity with non-artistic knowledge. Especially when art and research are purposely combined, one of the main aims is to import a great amount of non-artistic knowledge and methodological tools into the four types of artistic knowledge production in order to nourish and empower them. Without this kind of external input, artistic knowledge can hardly be developed very far.

For example, if we were to study, research, and develop portrait painting – either through painting, photography, or writing about paintings and photos – we would not get very far if we paid no attention to what contemporary philosophy, psychology, and social theory have to say about the structure of the self.

It is difficult for an artist to become a real specialist in any non-artistic field of knowledge, but combining art and research inevitably means that this is something one has to try – one has to try to juggle with a number of separate balls from various fields of knowledge. This juggling act is the very essence of most forms of artistic research, especially of those in which art is seen as a politically active practice. And this political activeness and philosophical alertness is of course precisely what not only Brecht but also Theodor Adorno (1903–69), Michel Foucault (1926–84), Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908–61), and numerous others demanded from contemporary art.

ART AS A PHILOSOPHICAL-POLITICAL PRACTICE

I have proposed that we should acknowledge art (at least potentially) as research. I have also proposed that we can, in principle, organise artistic knowledge into four categories, one of which is ‘art's knowledge about the world’. I have also claimed that this knowledge can be verbal or nonverbal, conscious or subconscious, but I will now try to define more closely what kind of knowledge it is, how it relates to other types of knowledge, and what its function in society is.

Art can be a flexible and extended form of philosophy and politics. Art does not have to be content with ‘asking good questions’ only – it can also try to answer them.

Immediately we hear a bunch of sceptical questions: With what muscles can art supposedly answer the ‘good questions it proposes’? After all, aren't the answers always created elsewhere – for example, in the fields of science, technology, or philosophical theories and their political applications? If art tries to step into the fields of knowledge and ethics, can it adopt roles other than those of a communicator and copywriter; can art be anything more than just illustration, communication, and the persuasion technology of, say, the Enlightenment and human rights philosophy?

For the answer to be ‘yes, it can’, and for art to be seen as a form of critical thinking and action that deserves to be taken seriously, we must redefine art’s relationship to knowledge, values, worldview, and pleasure. For example, like this:

(A)

Art also creates, tests, and spreads quite regular knowledge, that which can be verbalised, verified, and distributed with precision. In this function, art can use either methods that are more general or, alternatively, methods that are characteristic only of art. It is because of the latter kinds of methods that art is also able to create knowledge that would otherwise not be created at all. For example, the methodology used in a research survey can also be used in art. Moreover, it is possible to carry out, say, a preliminary statistical study for an artwork, but in addition to these methods – or in their place – art can make use of various other methods, including participatory intervention in a public space, performance, or a false advertisement. These can also be used to acquire knowledge of people’s behaviour and values or to communicate to them different points of view and their rationales. It is often acknowledged that art is an effective form of communication and that it is able to convey values and knowledge in a particularly dense and heartfelt form. However, it should also be recognised that art is not only a communication method but also a method for creating knowledge and understanding. In this sense, so-called political art by its aspirations and goals is often very close to everyday journalism, discourse, and politics.

(B)

Art may spread regular, verbalisable knowledge in a very compact and striking form. It's an efficient form of knowledge distribution, when it wants to be.

... but what is even more special and valuable is the fact that:

(C)

Art makes experientially true values and knowledge that we otherwise would often adopt only superficially.

One can have, for example, mathematical-rational, factual knowledge of how to create and nourish reciprocal trust and love in human relationships, about how and to what extent buying Fair Trade bananas reduces exploitation,8 or about how to fight climate change, but this knowledge does not necessarily lead to action. Why? The usual explanation is that knowledge is not enough if one does not have the courage, diligence, and moral drive to do in practice what one supports in theory. However, we can also extend the definition of knowledge and say that the mathematical-rational knowledge described above is merely one breed of knowledge and that the aforementioned passivity is not so much a case of emotions defeating knowledge, which would leave knowledge unused, but instead a case of knowledge remaining merely an incomplete stump, a mere list of information or principles, which we do not take seriously because we have not really internalised it.

Knowledge that we have learned but which we have not fully digested, knowledge that we assume we know but do not take seriously and do not put into action, is not really our knowledge, but just an antecedent, a grain of knowledge that only becomes nourishing when it's cultivated into a fully grown plant. Of course this is partially a matter of figures of speech: Is knowledge that does not lead into the action it necessitates just knowledge I've decided to leave unused, or is it knowledge that I mistakenly believe I know but which has not grown into anything more than a helpless stump? On the other hand this is more than just a matter of metaphors, it's about how we should define knowing. I'm in favour of the version where knowing includes internalising the knowledge so physically or holistically that one cannot leave it unused, but is forced to behave in the way the knowledge demands or to counter it with some other serious bit of knowledge or moral reasoning.

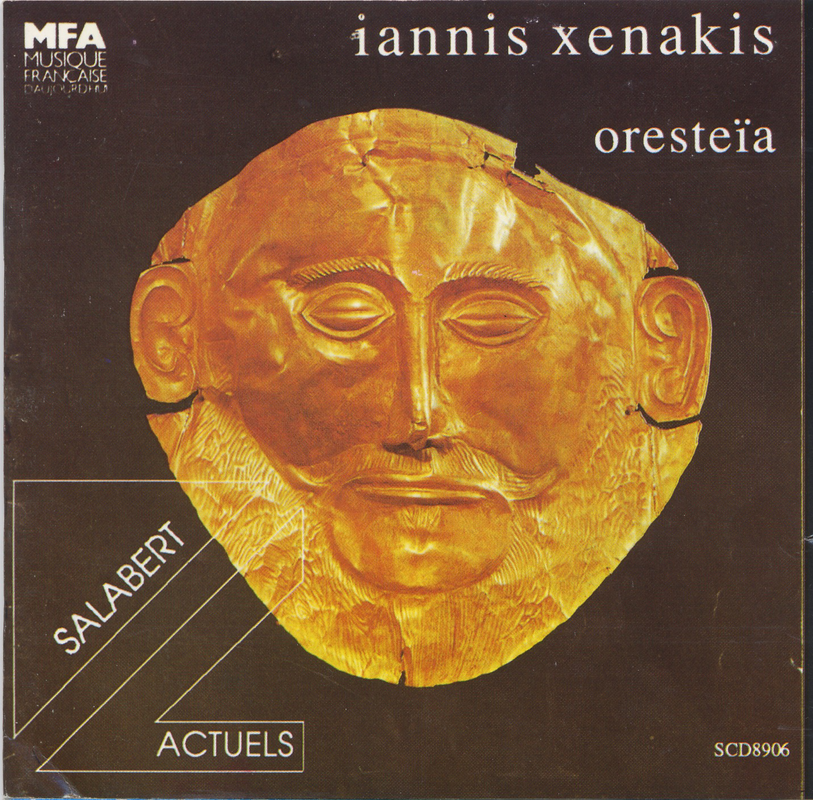

A large part of what we know is of this type – we have not really digested it. We also put into practice only a few of the values that we praise in principle. Knowledge and the raw material of values tend to pass through our mental digestive system without actually being absorbed, leaving a trace, or having an influence on our behaviour. Correcting this failure is one of the basic functions of art. We can do this, for example, by following the teachings of virtue ethics, by using art as a way of training and intensifying our positive emotions and personal characteristics. Shoah (1985), a documentary by the philosopher-artist Claude Lanzmann (1925–), forces the viewer to ponder the Holocaust in a more embodied, experiential way than history books do. And the Oresteia trilogy (Agamemnon, Choephoroi, and Eumenides, 458 BC) by Aeschylus (525–456 BC) can intensify our sense of compassion and make us understand the relativity of justice more efficiently than any non-artistic method.

These works guide us to sympathise with all the characters, thus making us understand the conflict from several points of view simultaneously. On the other hand, they distance us from individual perspectives and agitations and challenge us to consider the conflict more rationally. Works such as these are an important form of moral philosophy because in them we can think of values in a way that on one hand is passionate, compassionate, and assimilative, but on the other hand clearheaded and analytic, as if the entirety was simultaneously examined from a bird’s eye view too.

(D)

Art creates and distributes the kind of silent, tacit, or experiential knowledge and values that are only partially verbalisable. Art (and philosophy) are essential, because values cannot be derived from mere facts. In other words: from how things are we cannot directly draw any conclusions about how things should be. David Hume (1717–76) formulated this idea compactly as "there is no ought from is" in his Treatise of Human Nature (1739–40). Moral realists, ethical naturalists, and many utilitarians disagree on this, of course, but it is still fair to say that for many or for most in contemporary philosophy and politics the central dilemma is: How to make the leap from facts to values? What can moral reasoning be based on, how can we make moral choices without pretending that all that is needed to support them is objective reasoning with pure facts? On the other hand, how is it possible to prevent moral reasoning from collapsing into mere matters of taste? The challenge is especially fierce today, when conflicting moral systems and traditions collide in our globalised world, more and more often without a shared or objective measuring stick or an authority that could solve their conflicts. Moral discourse is more necessary than ever, but unfortunately it is increasingly often avoided by delegating value statements to the ‘blind hand’ of market forces.

Values float somewhere between facts and subjective statements, so in testing and creating them, neither sheer feeling nor clean, clinical reasoning is enough. Art operates in this unclear territory, dwelling on questions, such as ‘how does it feel?’, ‘how is it?’, ‘what do I really fear, and what do I really want?’, ‘why should we keep on living, and what makes my life worth living?’, ‘how does one make a life out of mere living?’, ‘how should we live?’, ‘how does one be a man or a woman and why?’, and ‘what is good life?’.

Art includes much verbalised or verbalisable reasoning, but art's greatest strength is in the continuation of thinking beyond verbalisable reasoning. Especially when perceiving, testing, and creating values, this is an essential dimension, since the ability to appreciate things, the will to live, and the joy of living are mainly experiences, not conclusions of rational pondering. Art is the most efficient (though not the most used) human-made method for moulding our lifeworld, and thus an excellent form of innovative and embodied moral pondering.

(E)

In art we shape our worldviews in their most complete and full-bodied form. A person's philosophical-political conviction is not just a collection of verbalised propositions and their rationale. It is a more extensive, holistic thing: a worldview, an outlook on life, some kind of multisensory vision of what has been, what could be, and what one would like the world and the self to become and how.

When this full-bodied visionary form of the philosophical-political conviction is then tamed into neutral, matter-of-fact, fully verbalised argumentation, a secondary form of worldview is created. It is an attempt to condense the primary form into something more easily manageable, into something that can be communicated with fewer misunderstandings and justified more easily.

In art, there is room for straightforward philosophical-political argumentation, but of greater importance is the creation, testing, and expression of worldviews as artistic visions, without any pressing need to translate them clumsily, step by step, into a verbalised argument.

(F)

Art is a good method for dealing with questions and problems for which there is no final answer or solution, but that we still have to face in one way or another.

For example, the previously mentioned ‘what is good life?’ is a question that cannot been solved like a mathematical equation. Mortality is another, similar challenge. On the one hand, it is simply an enemy that we fight when trying to reduce the infant mortality rate. On the other hand, it is something very different. We can philosophically reason that mortality is a part of life, not an enemy of life, and that if one wants to live well, then one has to come to terms with one's mortality somehow, maybe even learn to praise mortality as the ultimate source of all passion and the creation of values.

Yet no matter how hard one intellectually toils away with either, the challenge of mortality will not be resolved. We cannot solve it like a crossword puzzle – not even if infant mortality was reduced to zero – as our relationship with death is contradictory and filled with tension in such a fundamental way.

In art, we try to adjust and compose this relationship and this tension, so that it will be as pleasurable, meaningful, and life-affirming as possible. Of course, art does not have a monopoly on this kind of adjustment. Surely, for example, politics is also often about facing the same kinds of problems, which cannot be permanently solved in the way problems caused by technical obstacles can. Polio can be totally eradicated from the world, but balancing rights and responsibilities is a permanent challenge for societies and individuals as well. Nevertheless, in art, this adjustment of life often reaches its most complex form: that in which the question is no longer about solving problems in the technical sense, nor is it about composition in the simple sense of balancing a few elements on a horizontal equilibrium, similar to scales or a seesaw, it is about composing the whole of a life, without rules and without any other clear goal than good life – the criteria of which remain permanently open.

(G)

It is harder to read a good poem than to write it.9 This is the opening line of a poem of mine, and it is my honest opinion that one of the special features of art is that consuming art is often as difficult as making art: it requires as much effort, expertise, patience and enthusiasm. This is why three things – work, the fruits of one’s labour and the enjoyment of these fruits – come together differently in art than in normal production and consumption. In a culture that focuses on possession and consumption, these three aspects are sharply divided from one another: the enjoyment you get from your work is measured by your pay, the fruits of your labour are the things you can acquire with the money you get, and the enjoyment of these fruits means that you lie down on a flying carpet – the opposite of labour.

In art, however, this division is invalid. In art we try to learn to live our lives in a different way: to love existence and mental struggle and to accept that building and owning the instruments of pleasure and the external preconditions of pleasure is, at best, only half the journey. To know how to enjoy things and to practice one’s skills of enjoyment require at least as much effort.

NOT ONLY FOR KNOWLEDGE – THE SPECIAL FEATURES OF ARTISTIC RESEARCH

There is often strong resistance against acknowledging art as a potentially valid mode of research. Of course, many find the idea of art as research laughable, but the more moderate mode – where art is made, not instead of written theory, but together with it as a holistic form of research – is also widely dismissed.

Perhaps the most typical argument against the broadening of the acknowledged, art-excluding paths of research and definitions of knowledge is the one that can be called the objectivity argument. It goes approximately like this: ‘Science is objective, or at least objective enough, so that its achievements and progress can be regarded as undeniable and its proposals tested in a reliable, nonsubjective manner. Artworks and artistic practice are far removed from these principles and should therefore not be included in the repertoire of valid research.’

The claim is false, because

(1)

Artistic research can use the same qualitative and interpretative research methods that have already been widely tested and approved in science, and which can thus produce relatively reliable knowledge. Moreover, as far as reliability is concerned, it is important to see, on the other hand, that most if not all knowledge is always only relatively objective and relatively reliable. Proof of this is easy to find not only in philosophy but also in the fields of the ‘hard sciences’ and economics. Art is not less reliable or controversial than, for example, economics: again I bring up Milton Friedman, perhaps the most influential economist of the last one-hundred years, who received the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1976. Already in the 1970s some economists, and nowadays many more, saw Friedman's basic claims, arguments, and conclusions as disastrously false; yet, equally, there are many economists who still consider the same claims to be valid. No consensus is in sight – sounds a lot like art.

(2)

Artistic research does not necessarily aim at objective, value-free knowledge. Quite the contrary, it often aims to produce situated, perspectival, knowledge and ‘impure’ knowledge, which is not about objective, value-free facts, but instead about testing and creating values. Art is often able to deal with philosophical-political questions precisely because it is not limited by so-called objectivity.

Another typical argument against the combination of art and research is the shareability argument, which claims that ‘Even if art could produce research results that are undeniably enlightening and useful for its maker, it is still mainly just personal knowledge, which cannot be reliably shared as nonsubjective, written theory can. Art can perhaps produce subjective knowledge, but it cannot share it reliably and thus cannot be research or even part of research.’

The claim is false, because

(1)

Research results can often be successfully expressed not only by declarative sentences but also and more efficiently by other means. When a musician joins a band led by a more experienced master, s/he often learns about the technique and content of the music mainly or only by playing, without any verbal communication or writing. This kind of learning-by-doing is just one example how real, not mysterious, tacit knowledge and its sharing can be. Often, observers who do not participate in the act they witness – a musicologist in this case – can surely detect and verbally describe what the tacit knowledge is and how it was passed on from one person to another. Yet, in this case, the verbal description is secondary knowledge, mostly just a description of the primary knowledge – and the essential knowledge remains in its wordless and experiential form. The musicians have the knowledge, and even though they do not necessarily verbalise or even verbally describe it, it is still reasonable to call it knowledge rather than random acts, not just habits or matters of taste, not just shared emotion or something like that, because from the results we can positively detect a systematic, goal-oriented process and progress.

(2)

Artistic knowledge does not always have to be shareable – it is enough that artworks are. When an artist is able to improve the artistic results of his/her artistic practice clearly, it is reasonable to assume that it is not accidental, but instead a result of some kind of research, no matter whether s/he can verbally share the research process. In the technical or purely theoretical sciences, this lack of shareability would be fatal, as they are instrumental sciences where the results are useful only if they can be shared as exact knowledge. However, many people can use an artwork as such, and in this sense it can be shareable and usable as it is. It is thus fundamentally different from purely theoretical knowledge, which has to be precisely verbalisable, and which through this verbalisation can be put to practical use (or reliably combined with other bits of theoretical knowledge). Let us imagine a scientist who invents and makes a pair of scissors but is unable to explain how he did it and is even unable to make another pair. Let us also imagine that there are other people who can use the scissors but who are somehow unable to figure out how they work and how more scissors could be made. There would be only one pair of scissors in the world. This unshareability of knowledge would make the invention fairly insignificant, because the most valuable thing, the transferable idea and the blueprint of the scissors, would remain a mystery. In the arts, things are different, because even knowledge that remains completely personal can lead to the creation of significant things. James Joyce (1882–1941) was able to write Ulysses (1922) and Robert Musil (1880–1942) Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften [The Man without Qualities] (1930–42). These are great achievements, no matter how much we can know about the writing process and the intentions of their writers. The fourth type of artistic knowledge, art's knowledge about the world, is there in the artworks and can be shared and used by an endless multitude of people, not as a fixed, cemented body of knowledge but as a flexible source that can be used with various personal approaches and interpretations – and that is enough.

I have tried to prove that there is knowledge in art and in artistic processes and that they can also produce new knowledge, but what I have said is not quite enough, something more is needed to fully understand the function and justification of artistic research.

First, it is fairly obvious that in making and in consuming art we do not only strive for knowledge. I propose that art essentially has four widely accepted functions:

- Giving pleasure (including both the pleasure of escaping/forgetting reality and the pleasure of facing the reality as intensively as possible)

- Sparking discussions (that is, ‘asks good questions')

- Striving after wisdom (including both solvable problems and eternally open questions – for example, the definition of good life)

- Cultivating our emotional life10

Knowledge may be the main ingredient in only one of these four functions. Even in that function knowledge is not valued and used only as a problem-solving tool, it is regarded as having a worth equal or higher as a tool for testing and creating values. Yet, success in each of the four proposed functions of art require organised, systematic, goal-oriented artistic processes – in other words, research. At the beginning of this essay, I defined research as a systematic procedure that either (A) increases empirical, logical, or other type of verbalisable knowledge or (B) improves our performance in the function in which we try to excel. I have also said that knowledge is a mental or physical skill, which makes us better able to do something, use something, or predict a future activity of something. The traditional definition would have stated that research is an organised pursuit of knowledge,11 but with these new, flexible definitions, research is set free to pursue other things too.

Thus, to sum up, the most obvious special features of artistic research are:

- Its processes and research results are only partially verbalisable.

- The knowledge used and produced by it does not always have to be shareable if the resulting artworks are instead.

- It aims at producing knowledge both as artworks and as theoretical texts, but it also aims at other things: ethical, aesthetic, and experiential values and holistically rewarding experiences.

VARIOUS TRADITIONS OF COMBINING ART AND RESEARCH

Thus, attempts to combine art with research are now taking place in a kind of battlefield where various definitions of art, knowledge, and research are constantly wrestling with one another. The struggle is inevitably leading toward a wider acceptance of the extended concept of knowledge because the research conducted in universities has so effectively revealed the limitations of purely verbalised knowledge and thus created a need for a wider spectrum of knowledge and research. Another reason is that the world outside the universities has pragmatically expanded the definition of knowledge and the methodology of research – in this matter the universities have by no means been a spearhead. For the arts, it is essential to implement this expansion also in the university context so that the university becomes as good a place to practice art as it is to practice science. Paradoxically, however, the prime movers of this change in universities have not usually been departments of art or art universities, but rather departments of philosophy and sociology. Art universities have often clung on to the old academic criteria much more steadfastly than the university field in general, although certainly the average university scene can also frequently try to prevent artistic research from spreading; for example, in Germany, only Weimar and Hamburg have thus far opened their doors to artists for practice-based doctoral studies.

The process seems to advance in a direction where, one by one, new combinations of art and research are added to the list of valid forms of research; but the process will not necessarily ever reach such extremes that art as such – just art – would commonly be considered to be research in the academic sense of the word.

To make an inventory of the situation, I want to step back and look more moderately and closely at the various ways in which art has been included in research practices and regarded as a part of research. I will also try to evaluate the plusses and minuses of each form.

The disagreement and confusion over how to combine art with research is, of course, a result of the great variety of methods used to make the combination. However, as I have tried to show, the variety itself is explained by the many separate directions that the combination of art and research can take. Artists themselves can have many kinds of aims when they combine art and research and, for their part, the academic world also sees the function of the combination in many different ways.

There are at least five separate and partly conflicting basic views on how art and research should be combined:

1.

RESEARCH FOR ART (research as a tool for making art)

Research-for-art is a basic part of almost any artistic practice. Most artists feel the need to gather non-artistic knowledge about the themes of their artworks or about the techniques they use to feed their artistic practice – and some of the techniques are non-artistic or have only become artistic through their adoption into the artist’s toolbox. For example, painters (even today) are required to learn about human anatomy and optical colour theory as a vital part of their studies – fields of knowledge that are not artistic as such, but purely scientific. This, of course, merely adopts existing knowledge and appropriates it for artistic use, but it is research nonetheless as it is a process where old knowledge is used in a new situation and context.

Sometimes this urge to acquire useful knowledge and develop new methods has even made the artist a pioneer in a non-artistic discipline as well, as happened when Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) studied the human anatomy so intensively that he was able to produce actual new knowledge about it, not just new knowledge about how to represent and use it in painting and drawing.

Artists also often come up with technical innovations that extend their toolbox (or palette). Leonardo, of course, is also the archetypal example of this, due not only to his research on anatomy and its pictorial representation but also, for example, to his relentless attempts at developing new painting techniques, which, while they often failed, still produced knowledge that was valuable for the later developers.12 When it comes to such developments, we should not merely stare at the Renaissance in awe – similar developments are now even more common in all the arts because technical progress is everywhere so rapid. For example, in electronic arts, the artists themselves often lead the development of the devices and software they need in their video art, VJ practice, and interactive media art and in the composition of electronic music.

The positive potential of model 1 (art using research as one of its tools):

- Most artists need non-artistic knowledge of their themes, and as the world is getting technically, politically, ethically, and ecologically more complex, this need is constantly growing. Without it, art as a philosophical-political practice easily ends up being naive and confused.

- When artists develop their own techniques and technologies from scratch, or when they develop existing technologies further, they empower themselves instead of remaining imprisoned by the boundaries and the implicit worldview of what the technological industry has produced.

- The university system has no problems with this kind of combination of art and research. As long as the concept of knowledge is as clear as it is in the case of technical problems and technical innovations, the traditional university system can feel that the research and art game is played on the university's home turf.

Risks and downsides of model 1 (art using research as one of its tools):

- The knowledge gathered as thematic raw material or background information does not automatically lead to better artworks, although it makes better artworks more probable.

- Technical innovations do not automatically lead to better artworks. They do not even make them more probable.

- This way of joining research with art can unintentionally participate in the upholding of the simplistic opposition between research and art. This is similar to the pattern where research is seen as the hunt for ‘hard facts’ and art as only the search for ‘semi-subjective, aesthetic pleasure’.

2.

RESEARCH OF ART

Art can be researched like any other phenomenon. Not only art historians but also researchers of aesthetics, psychology, sociology, general history, philosophy, politics, and anthropology have often focussed on art. Sometimes the aim has been to understand and explain art, but at least equally often the goal has been to understand, explain, claim, and prove something about our society and human behaviour in general. And now artists themselves are researching art as doctoral candidates or post-doctoral researchers.

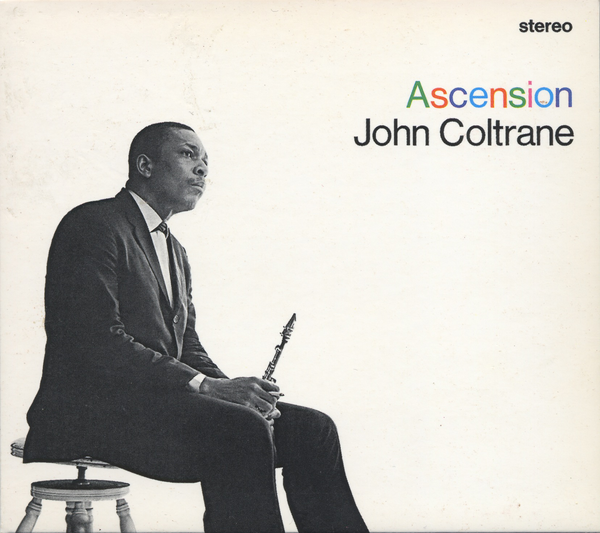

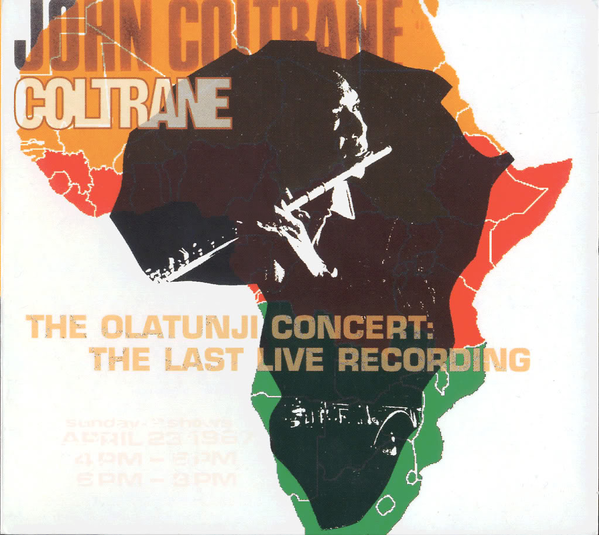

On the other hand, it is probably obvious to all that artistic practice is always based on some kind of intensive study of what has been done before (in the arts), and also that right now there are far more tenor sax players dissecting and analysing the music of John Coltrane (1926–67) than there are musicologists focusing on the same subject – and that potentially both are doing research with similar intensity and insightfulness. The difference is, of course, that the end result of the musicologists' research is a written analysis and theory, whereas the end result of the musicians' research often remains unverbalised and private. If it is shared, this will take place in workshops where the musician shares his/her findings by playing the music with his/her students or fellow musicians. We can even go as far as to say that the act of playing the music is already in itself a way of researching its antecedents and that the end result, the music which is heard and possibly recorded, is thus the result of this method of research.

But I am now getting ahead of things, since the example and comparison above belong to the realm of so-called artistic research instead of conventional academic research practices of art. The conventional academic understanding of how art should be researched has been created by the kinds of learned people who do not make art themselves and for whom the normal or the only valid mode of doing research and stating research results is writing. Because of this, it is quite understandable that when artists now attempt to research art also in the academic context, they are often automatically expected to use the same research practices that non-artists have found useful.

However, one concession has recently been made to this strict academic definition of research practices. It is now common to think of an artist’s hands-on experience of art making as an asset rather than an obstacle that hinders ‘objective’ research. This ‘insider's knowledge’ is now seen as a valuable, additional research instrument or as a source of insights. Thus, it is now reasonable even to encourage artists also to take up academic research.

Nevertheless, the concessions usually end there, and artists are required to carry out their actual research with the same writing-centred methods used, for example, by art historians, or concentrate on analysing statistical data similarly to an economist. In other words, the research result must be an academic dissertation in the pure form of a verbalised, written text.13

3.

ART FOR RESEARCH (Research using art as one of its tools)

Sometimes art is used as one of the tools of research, as a research aide, and the research topic is non-artistic. The aforementioned ‘research for art’ and ‘research of art’ are branches of research that focus on art and aim to produce knowledge about art or develop better methods for artistic practice. In the ‘art for research’ branch this is reversed: now the goal is to know more about a non-artistic topic and use art, art-based practices, or the artist's special perspective as a tool of enquiry subordinate to non-artistic research.

Art for research can be made, for example, by using the researcher's own artworks and artistic processes as raw data or as research tools, which would be comparable to interviews or lab experiments used in normal academic research. We can, for example, think that participatory performance art or collective painting workshops – in conjunction with observation and interviews of its participants – could be especially rich ways of gathering data in qualitative and interpretative research.

However, in this model the actual research, the development of a theory and argument, is still conducted mainly, or only, through writing. The artworks included in the research process are seen merely as tools, and their quality as independent artworks is considered irrelevant to the research. This is the most fundamental difference between ‘art for research’ and the kind of art or combinations of art and research that also try to investigate non-artistic topics, such as social, political, or philosophical concerns. In ‘art for research’, artworks are never regarded as research results, nor are they considered to have any explanatory or argumentative power of their own.

Thus, in this branch, too, the expected research result is a dissertation in the form of a verbalised text. Artworks may ‘accompany’ the research result, as a bonus element that illustrates the thoughts developed in the written theory or in the technical innovations created. Whether this enables the artist-researcher to make better art or not is thought to be beside the point, as the aim of research has been to accumulate written, theoretical, or technical knowledge.

An example of model 3: Matti Tainio (1967–); Art and Sport: Similarities in Cultural Practices (research title).

Tainio is an artist and a doctoral candidate at Aalto University School of Art and Design. His doctoral research project mainly investigates how aesthetic and artistic practices and ways of seeing, experiencing, and evaluating have trickled into the field of sports. He calls this process the ‘artification of sports’. His research method is based on his experience as a professional artist, an amateur sportsman, and a spectator of sports. Simultaneously with his research project, he makes artworks that deal with artification, but he does not include any of these artworks in his actual research and will not include any artworks in his research results. He wants to keep his research interest, at least the academic research interest, and his art-making almost clinically separate.

The positive potential of models 2 (research of art) and 3 (research using art as one of its tools):

- The scientific methods used have proved reliable through centuries of testing.

- It was only a short while ago that art became dissatisfied with its role as merely the object of research, where it was just languishing helplessly under the microscope. Because of this, art is still inexperienced and confused about what to do with its new prospects, with the ‘lab and its equipment’ that suddenly fell on its lap. Methods numbers 2 and 3 are sensibly cautious ways of developing new methods in this new situation.

- When artists make this kind of research, because of their special insider's view, they may produce knowledge that is different from what conventional art history, aesthetic theory, or cultural studies produce – different and thus valuable.

- These models of research also provide a safe escape for artists wanting to leave behind their artistic identity and adopt the identity of a researcher or a scholar. For some artists, and for art in general, it is good that the option of switching to academic research exists; an artist may lose interest and/or ability to make more artworks, but the love of art may still remain. Moreover, the ability to use artistic knowledge for something else might remain or be born. Ex-artists can then use their artistic expertise to produce written knowledge about art, the interpretation of art, methods of art, or art-based knowledge about something non-artistic.

- It is easy for the university system to deal with this type of research, to understand it, to evaluate it, and to share and distribute its results.

Risks and downsides of models 2 (research of art) and 3 (research that uses art as one of its tools):

- These modes of research are limited because they understand research and knowledge in such a narrow way.

- They also do not directly aim at making better art. From the viewpoint of the artists and art audience, this can be a pity.

- Moreover, they often lapse into a simulation of conventional academic practices. An artist might make a dissertation that would be considered embarrassing if a doctoral student of art history, aesthetics, cultural studies, sociology, or philosophy made it.

- Written theory may enslave art and non-written theory.14 Artists might lose interest and the courage or ability to make art and artistic choices that they cannot safely explain and justify with the verbalised theory they now completely espouse.

- Theory (instead of art) may become the real creation, the place where ingenious constructions are made, where radical statements are made, where the real substance of the whole thing is. Artworks are thus reduced to illustrative elements and stepping stones: less and less time and energy is spent with the actual artworks, while more and more time is put into reading and discussing art theory. This, of course, can be acceptable, but only when theory is indeed more insightful and pleasurable than the artworks on which it rides and to which it refers.

- Art may lose its ability to challenge and inspire rational thought or offer alternatives to theoretical texts. The living space or language divide: Jean-François Lyotard (1924–98) in a way spoke about this when he wrote about the différend, which disappears when art is forced to speak in languages that are not its own. Art may then obediently learn the languages of thoroughly verbalised systems – start using them like a good pupil – and thus give away its potential of creating languages of its own, languages that might be able to understand and express things that other languages cannot detect.

- The connection between the artwork and written theory may vanish or become a question of belief. An uncommunicative lump of something is thrown on the museum floor, after which the artist spends five-hundred pages explaining how the lump embodies all Merleau-Ponty's ideas in a physical form and even improves upon them.

- Artists concentrate on producing texts that make their artworks look better, deeper, and more insightful, instead of concentrating on making better art. If this happens, the quality of the artworks suffer, and theory may turn into solipsistic self-suggestion or scientific-sounding propaganda.

- If the propaganda of clever explanations succeeds, the art scene may, at least for a while, mistake mediocre or lousy artworks for great ones – and the combination of art and research may turn into a supporting crutch or even an overtaking lane that mediocre artists use to advance their careers as artists rather than as researchers.

4.

ART + WRITTEN THEORY = (artistic) RESEARCH

In this branch, both art making and theory writing are seen as research methods, and research results also include both artworks and theoretical texts. For example, a doctoral dissertation would consist of artworks and theoretical texts – and the artistic quality of the artworks is at least as important as the quality of the reasoning in the theoretical text. Art is considered to be research as such, but written research is practiced along with it. This is done to make the combination of research methods more comprehensive, to test the methods and findings of art-as-research, and to communicate the results. This is artistic research in the most versatile sense of the term, and to use the term meaningfully we have to give up the hierarchical structure where written theory was seen as the real knowledge and artworks just as the raw material for the theory – mere illustrations or field work tools – and replace it with a flexible view, where unverbalisable and partially verbalisable forms of knowledge can have the same status as verbalised knowledge. In this tradition, art is seen as a holistic attempt at understanding the self and the world better and as an activity that aims to change them both. The holistic principle requires the mixture of theory and practice and the simultaneous use of both verbalised and unverbalised thinking, means, and forms.

Five examples of model 4 (art + written theory = artistic research):

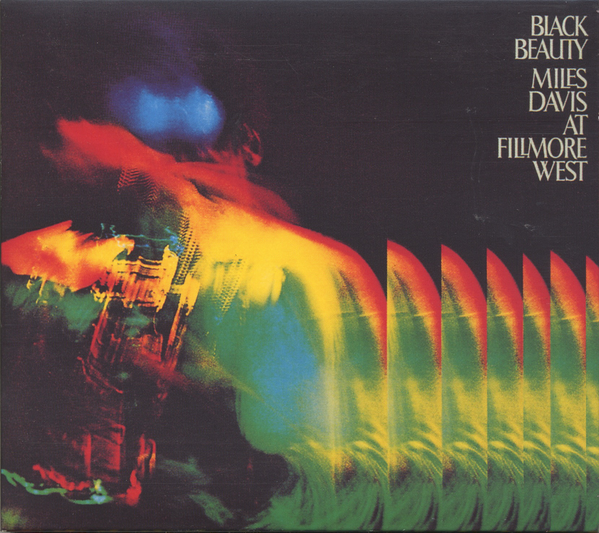

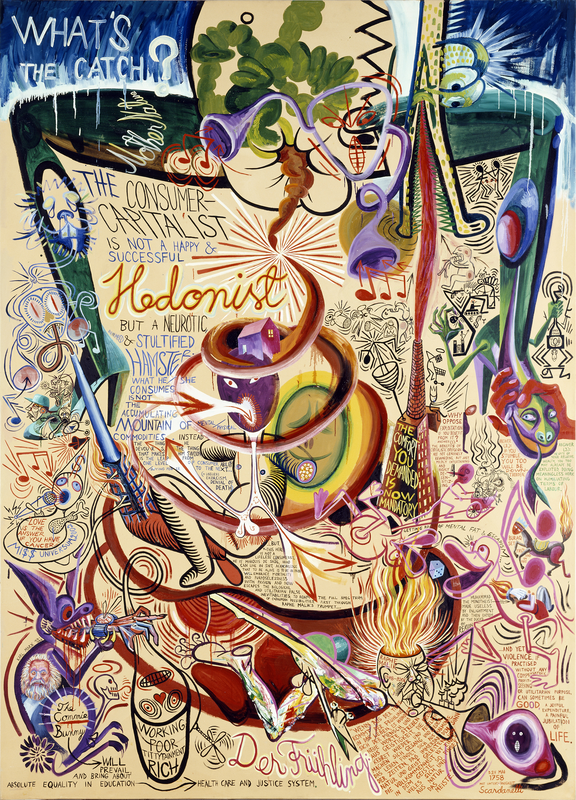

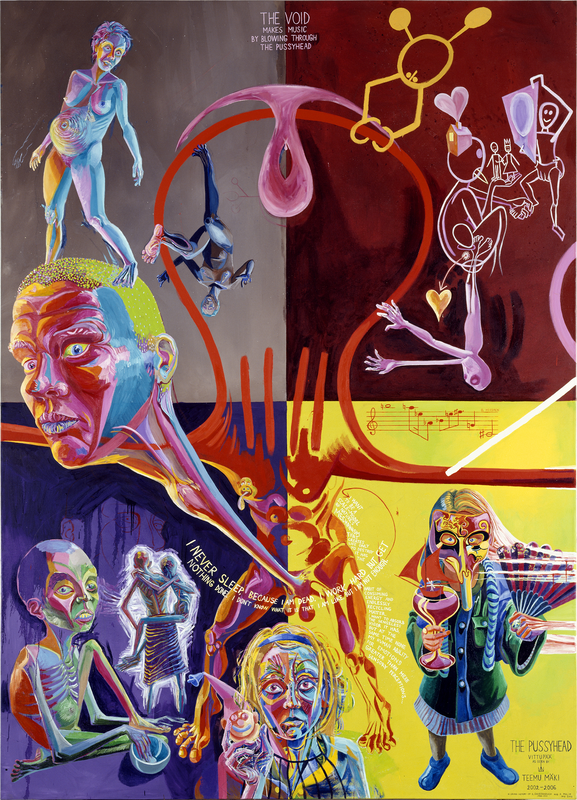

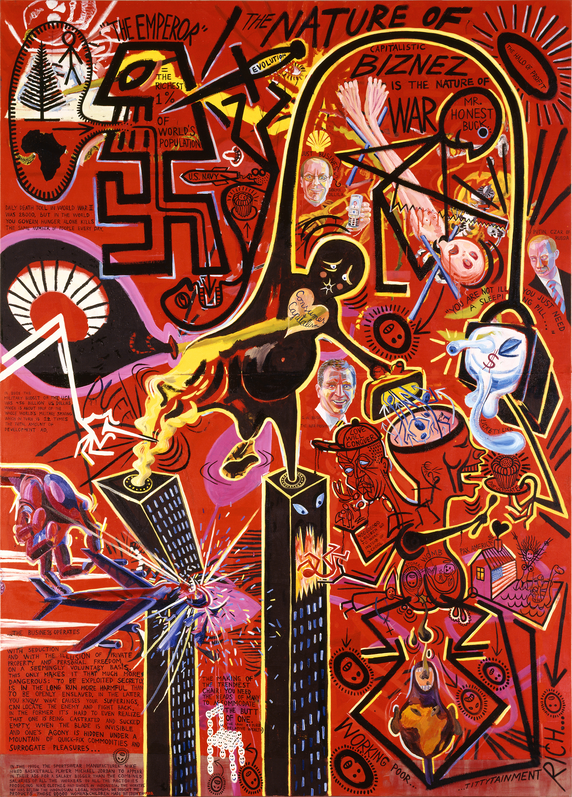

Example 1: paintings where texts and images intertwine or blur together

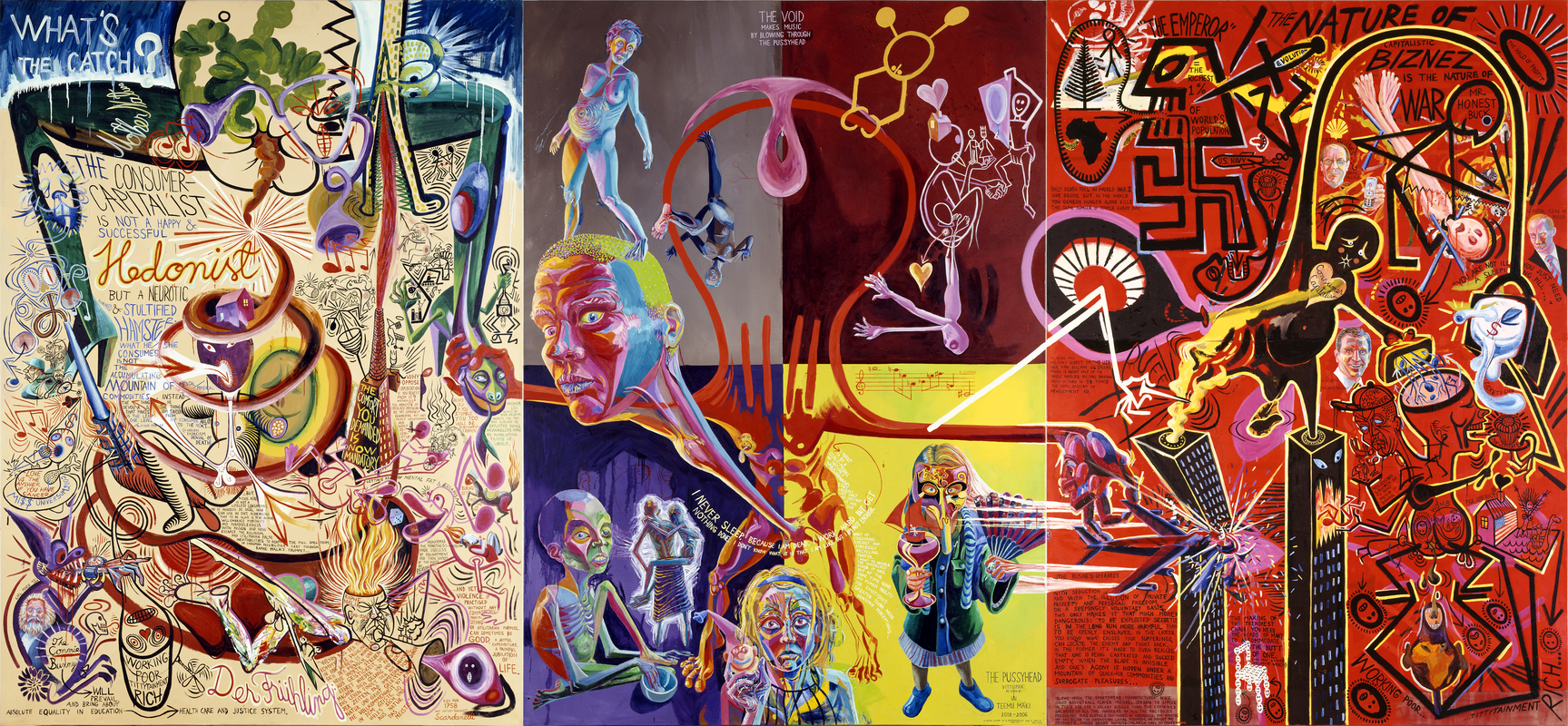

Teemu Mäki, The Pussyhead/Vittupää, 2002 – 1 December 2006, oil on canvas, 360 × 782 cm. An allegorical painting, which contains verbalised theory as arguments that are simply written directly onto the canvas among the more visual elements. A straightforward, crude way of cramming the nonverbal and the verbal argument into a single piece by force. Does this merge art and research? I think so, and it is part of a long tradition.