Entangled Fibres - an examination of human-material interaction

Doctoral Dissertation by Bilge Merve Aktaş, Aalto University, School of Arts, Design and Architecture, 2020.

Defended on 26.10.2020

Opponent: Prof. Elvin Karana, TU Delft, Netherlands

Custos: Prof. Maarit Mäkelä, Aalto University

The dissertation is available for download at https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/handle/123456789/47034

More information about the event: https://www.aalto.fi/en/events/defence-in-the-field-of-design-ma-bilge-aktas

Lectio Praecursoria

Since being in the womb and after being born into this world, we are always surrounded with materials. For instance, right at this moment, all of us are covered with textiles. I am covered with a woollen garment that keeps me warm. Only recently, I discovered that wool creates an itchy feeling on my skin. And whenever I wear a woollen garment, I want to move my body, touch my neck and scratch it. This simple reaction of my skin is a result of the dry weather in Finland and can be avoided by applying another material in-between my skin and the woollen garment, a moisturizing lotion.

This mundane and daily experience simply shows that our actions emerge through material interactions and these interactions can emerge differently under various circumstances. Although our bodies and minds react to these experiences, we are not always explicitly aware of how interacting with materials is an embedded and intrinsic part of our every day lives to the extent of shaping us. Perhaps for designers and craftspeople, this interaction is more recognizable since their practice significantly relies on being in contact with materials throughout the process of making. Makers need to understand how the material can behave since only after this realization they can join in the transformative flow of the material to make artefacts.

In this research, I examined human-material interaction in making processes to investigate how this interaction shapes the ways in which we make, think, and experience the world. In order to conduct a meticulous examination of this topic, I worked with felt making. Felting is based on unifying wool fibres to create a textile surface. Through applying friction and warmth between wool fibres, a nonwoven textile surface is created.

Wool fibres can be considered as sheep hair. And just like how all humans have different hair types, different breeds of sheep also have different kinds of fibres, such as long, short, thick, thin, curly or straight. When the maker begins working with raw wool, they begin their interaction with a distinct smell. The thick sheep oil covers the hands and leaves a feeling of heaviness while making them shiny. But if the maker begins by using the treated wool, which is already processed to be applied in felting, like this one here (the fourth example in the image), then they won't be able to recognize the length, curliness, the oil, or even the smell but only the softness and fluffiness.

If touching these different types of wool can create different sensorial experiences, can felting them also create various interactions while making an artefact? Indeed, every engagement with the material is an ideocratic togetherness of the maker, the material and making environment. These distinctive assemblages provide various possibilities of engaging with materials. For this reason, material’s role in design has been studied extensively. These studies identified making as a dialogue, a conversation, negotiation or even dance through which the maker does not force a preconceived idea but let herself and her ideas evolve with the material.

While examining making and designing processes with materials, despite identifying the process similar to a dialogue, the way it was studied often prioritized how this dialogue was perceived from the designer’s or the maker’s perspective. However, a dialogue means that there are at least two participants that make a point or an action and based on what one participant says the other one responds and this continues throughout the interaction.

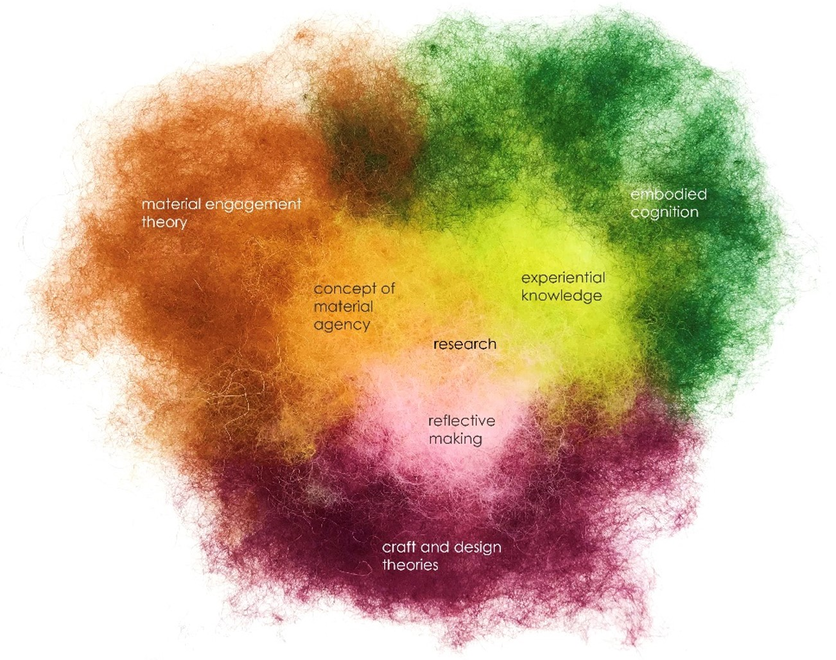

In this research, the other participants of the dialogue, specifically the material is investigated to empirically outline how making takes place in the intersection of reflective making, material agency, and experiential knowledge.

Bringing the material agency discussion proposes going beyond the experiences and expectations of humans. In this way, the relationship between humans and materials can be understood as an interaction that contests the instrumentalized perception of nonhumans. Through this lens, material agency as a concept enables investigating humans and nonhumans as equally significant partners of making. Acknowledging human material relationship as a dynamic process also enables new proposals about the practice beyond its utilitarian and functional boundaries. Following these ideas, this research tackles our participation in the world through making to emphasise the reciprocal transformations. What is particularly interesting in this discussion is to reveal how human agency entangles with material agency in and beyond making. To answer this question is to understand how we work, learn and live with materials by paying more attention to the embedded vitality of the material.

I developed four studies in the case of felting to examine how human-material interaction occurs and how material actively affects the making processes, this also became the main question of the research. Three of these studies focused on hands-on felt making processes on a personal level while linking to more general issues. The fourth study was designed to examine the extension of making to other practices and fields.

Rather than studying the material interaction as an observer, the research was designed in a way to study with the material, to become an integral part of the interaction. Accordingly, this research was conducted in the case of felting with a practice-led research approach. The practice-led research approach enabled participating in the vitality and activeness of the material while theoretically reflecting on these experiences. For this reason, the research relied on my own and other people’s personal experiences with the material. These personal experiences with wool and reflections emerging from them significantly informed the evolution of the research, the research questions, the studies and the theoretical positioning. The reflections entangled thinking with making while translating the implicit observations on the material into explicit insights.

In the first study, I worked with expert felt makers to examine how maker-material interaction shapes the bodily movements and the material movements in felting. Observing experts at their studios while participating in their everyday activities demonstrated the coupling between their body and wool. When we are making, we are essentially transforming materials in certain ways to manipulate their forms and create the ones that we initially intended. For instance, in the video, Gencer, who was one of the experts in the studio that I visited, is curving the sharp edges of his carpet. In each movement of his body, the material transforms and with each transformation, he continues moving his body in new ways. Throughout this process, the maker evaluates the design ideas or the emerging form in-action in order to make the next move. In this process, the body becomes united with the material so that the maker senses how the material is transforming and anticipates their own movement.

The first examination with expert makers showed that this coupling of the body and the material resembled negotiation: both the material and the body want to move in various directions however, they need to follow each other. The body needs to respond to the material transformations and movements so that an artefact of a common understanding can be created. Thus, the maker constantly reviews their pre-conceived intentions while the action is taking place.

Examinations on human-material interaction within various conditions indicated that humans and materials are entangled in ways that all participating entities, regardless of their being human or nonhuman, actively affect each other’s formation and transformation. Just as in a felted artefact, in an entangled organism, things come together to transform relationally. Similarly, in this research, the entanglement between the mind, the body and matter generated multiple understandings based on how entities come together.

With this research, I argue against the perception that humans lead their actions on their own. Rather, through their embedded agencies, things significantly shape the ways in which we think, act, experience and live. Humans and materials form a situated and relational coexistence. In our situated everyday experiences, we become one with materials, design with materials and think with materials. By discussing the togetherness of the human and the material, this research challenges established human values and fixed structures and proposes more fluid understandings of materials and their meanings, practices, responsibilities, and ways of being with the world. This also shows that we learn and grow with materials. Thus, materials can stimulate cultivating new models for teaching new skills: skills of crafting artefacts as well as crafting empathy towards building inclusive relationships with humans and nonhumans. This approach prompts an acknowledgement of other kinds of agencies and our dependencies on them. By embracing the coexistence of human and the nonhuman, the dissertation proposes valuing experience-oriented explorations over goal-oriented ones as well as processes rather than the outcomes in a way that distributes the agencies and actions among various stakeholders and spaces as well as overtime.

For a harmonious way of participating in the world, we need to focus on our relational emergences and be with the world. In this understanding, both human and material agencies emerge from their engagement. Our thinking and actions are embedded in dynamic relations with things that surround us. It is through the time we spend with this flux that we can understand how materials are shaping us.

Entangled Fibres - an examination of human-material interaction, Doctoral Dissertation by Bilge Merve Aktaş, Aalto University, School of Arts, Design and Architecture, 2020.

Contact: bilge.aktas@aalto.fi - bilgemerveaktas@gmail.com - researchgate/Bilge_Aktas

The dissertation is available for download at https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/handle/123456789/47034

The first two studies indicated that the material agency was actively affecting thinking through making on various levels such as thinking to develop pattern designs or to produce an artefact. Following these studies, in the third study, I examined how material interactions can extend everyday material experiences. For this examination, I designed a course to work with novice makers as they provide a valuable opportunity to observe early interactions with materials and their possible impact on shaping future experiences and conceptualizations.

As novice makers started interacting with materials and reflecting on these initial experiences, they also challenged themselves and questioned if they were able to control the material or if they were travelling with the material. By focusing on how materials can lead interactions, the participants of the third study, who were the students of the human-material interaction course, questioned established human values such as aesthetics or functionality. For instance, the student in the image explored materiality with the space and environment around her by following the sound created with her movements and the wool.

These reflections showed that when we try to understand our early experiences not merely from our point of views but from the coupling of the material and the maker, we can develop a relational perspective. This perspective can bring an understanding of being with the world, rather than only being in it.

In the second study, I examined how materials lead makers to develop their own ways of making and designing. For this study, I examined my own making processes to understand the material’s role in the ideation process when there are no preconceived ideas for the artefacts. The only intention in the process was to make artefacts that would look less like its designer and more like its material. Since the material was an active participant of the process, visiting it on its own environment became an ethical concern to understand it in its own way without human presence.

To start the dialogue of making beyond the design studio, I visited the countryside. Wool being part of sheep a living moving creature with a distinct smell, shades of colours and fibres covered with sheep oil as well as natural waste provided different experiences than working with the treated wool. Because once wool travels to the designer’s studio it is already treated for certain actions: for instance, it is washed and cleansed off from its natural features and carded well to put the fibres in line. Transforming the raw wool into treated one facilitates certain actions and certain types of experiences to work with it.

From observations on the wool the fibres became more visible than the wool lumps. In this study, a three-dimensional pattern design project was developed that played with tangling the fibres in order to create an artefact that would resemble the capacities of wool. The main approach was to prevent some parts from entangling. And here in this image, you can see how layers were created by not entangling all fibres.

At the end of the study, it also became clear that although initially, I started with following rules, as I gained more experiences with the wool’s activeness the material became the main informant of the process. The second main informant was my reflections on how I was experiencing the material. At this stage, the observations and reflections became tools to translate the material’s agency into the maker’s experiences. This study showed that making environment and the conditions of the material significantly shape how we perceive them and how we contextualize their meaning.

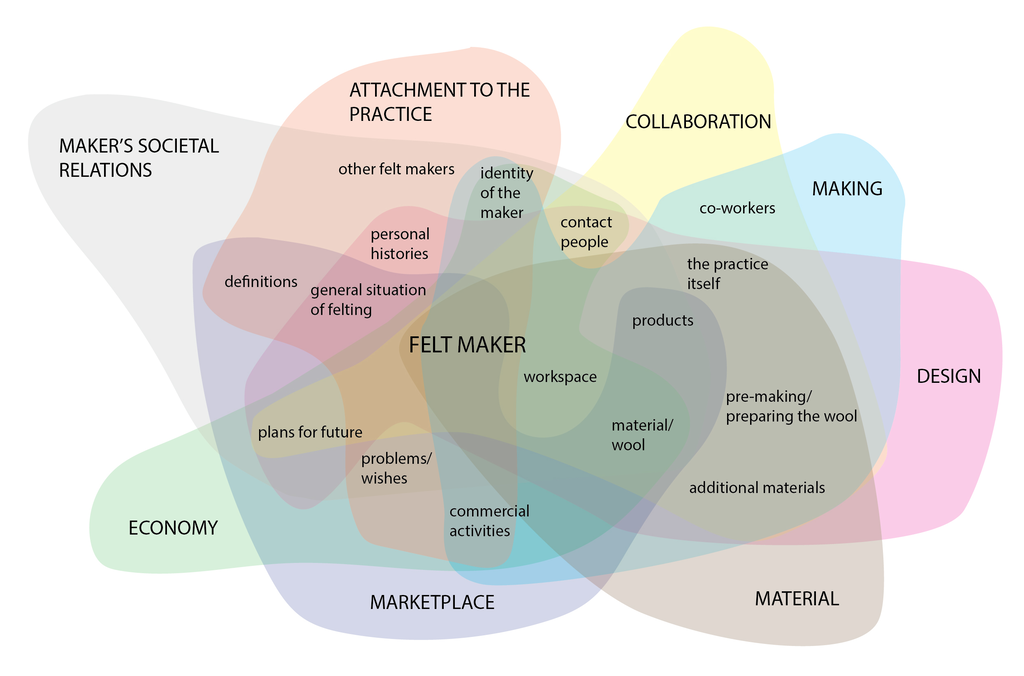

After examining how material shapes hands-on engagements, in the fourth study, the examination moved beyond the making process - I examined how material interactions shape various ways of becoming a maker. With this study, the aim was to understand how materials affect practices that are not only about making. By looking at significant aspects of everyday material and social engagements of felt makers, such as two expert makers who collaboratively run a studio, I was able to map how a felt maker needs to be in contact with a variety of people, materials, tools and spaces in order to continue their participation in felting.

This examination demonstrated that practices are materially connected and the relationship that the maker builds with the material shape their other relationships to such as: the workspace, making processes, designs, social relationships in terms of audiences or users, economic conditions, participation in the marketplace, collaborations and attachment to the practice. This connectedness and relatedness showed that despite identifications like craft practice or design practice, making is often a fluid experience that is in constant becoming in unification with materials.