sand: (noun) a collection of fragments, each grain moves individually, but there is also a collective movement

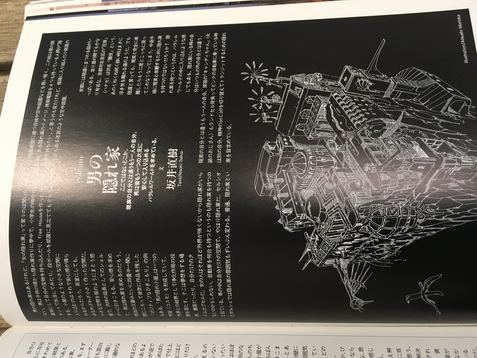

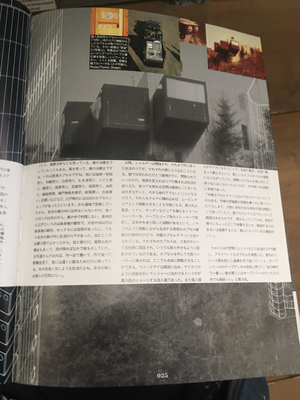

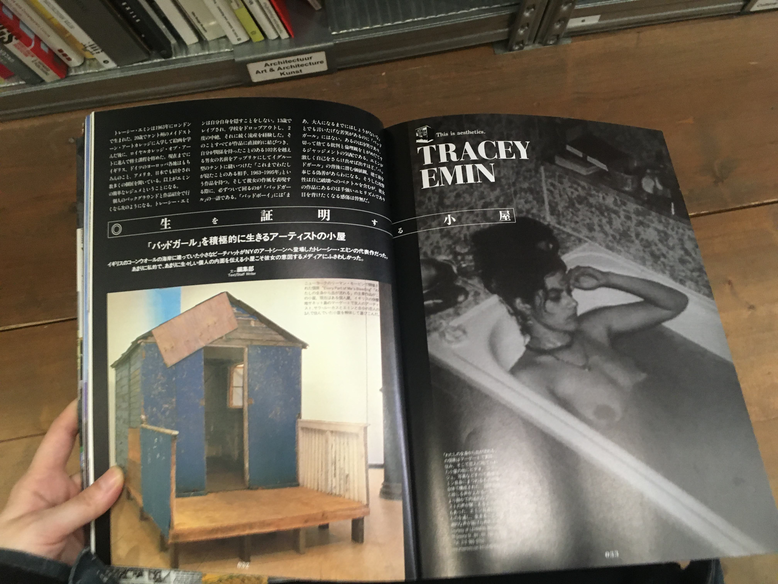

...Kyoto has many stories surrounding the hermit. A place famous mong drivers, 花背 (hanase) in Sakyo district of Kyoto city, is also called 離世 (hanase). That curved pass is very much like a road that departs from 浮き世 (the world/floating world/sad world/human society). But even if you say hermit, if you completely separate from reality, you can never return again. So, don't people need hideaway spaces to seclude themselves from the world only halfway? To have a hideaway is also like entering a parallel universe. The self in the hideaway is different from the usual self outside...

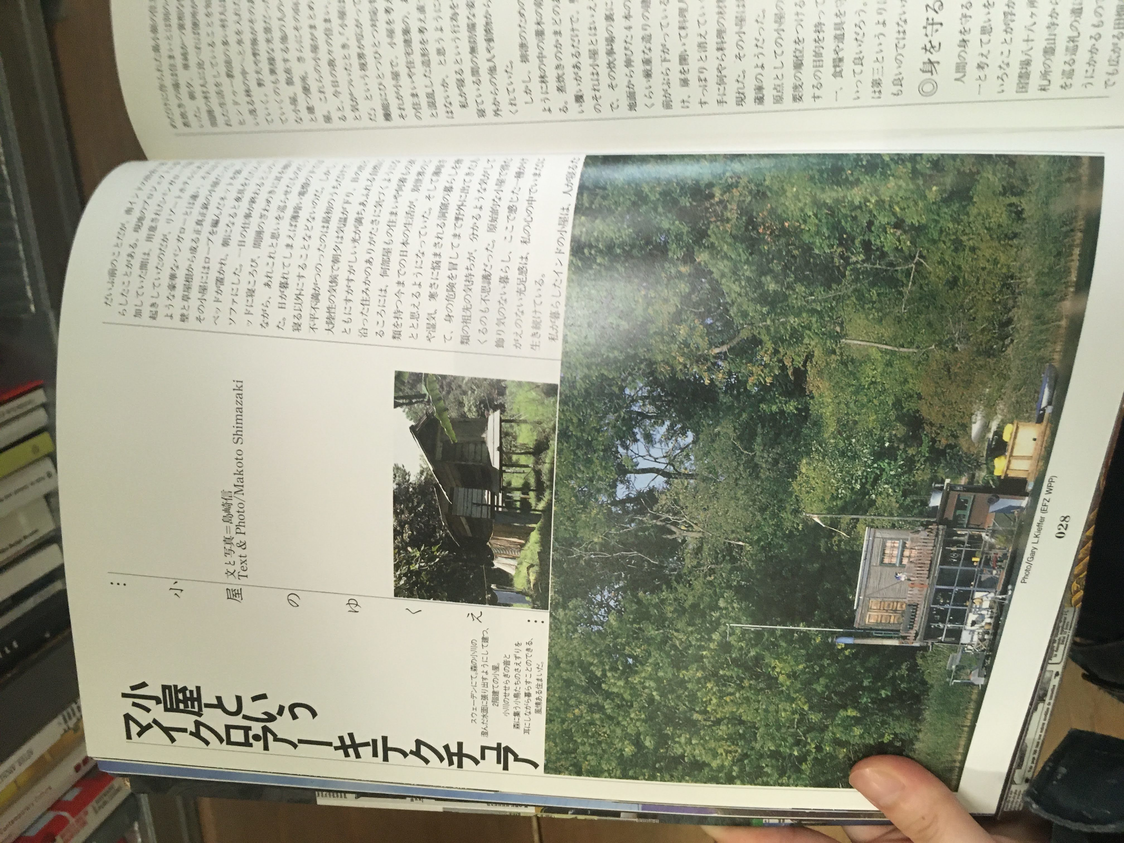

..."A hut(小屋) exists as well in America and Europe, but the characteristic of the Japanese hut is that it is not a place to cook or shower. It is originally meant to be a protection against rain and wind. For the toilet, you go out and wipe with a leaf. It's sometimes called 雪隠 (hiding with snow). Cool. To hide in the snow is a very Japanese way of calling it. In the book The Era of the Nomad, I made a paradoxical statement that the Edo-period was one of the most nomadic lifestyles in the world, but the core of the lifestyle in this era was flooding in the town"...

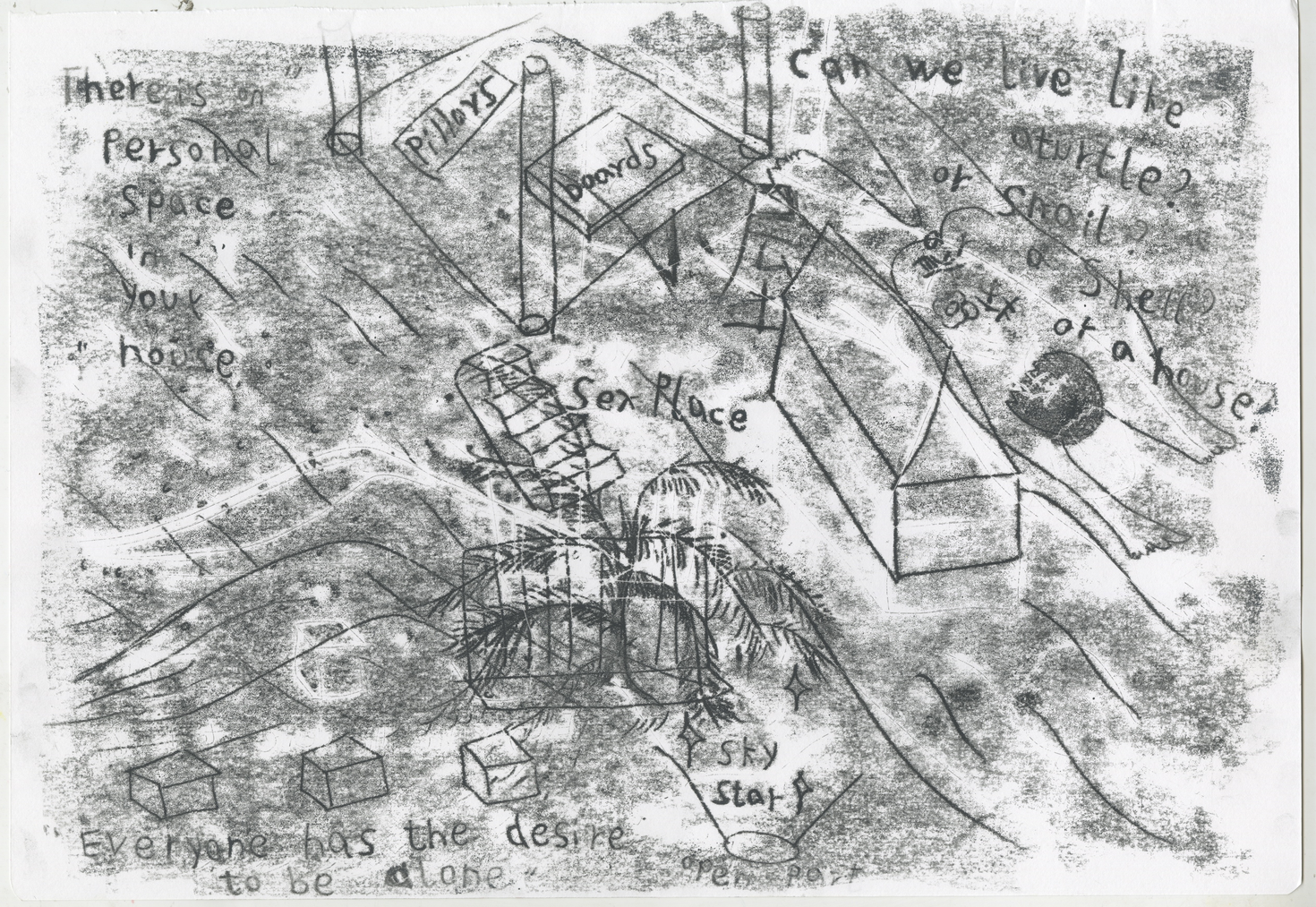

..."Then, the essential core for living were the market stalls... it is said that there were about 500 capsule shops in the Edo-period. Because everyone was running their business in the streets, you didn't need anything in the house. You eat out so you don't cook in the house. Basically, Edo was the city for single people, everyone except for Samurai and Daimyo was singles. For sex there was Yoshiwara, so the core of the life was outside the house. The living place could be minimal so it was just pillars and boards. Sometimes the roof also just a board and you would open the umbrella when it rained. When the sun comes out you go out to work, eat out, watch Kabuki, and come home late at night just to sleep. Like the young people nowadays. There is no personal space in your house."

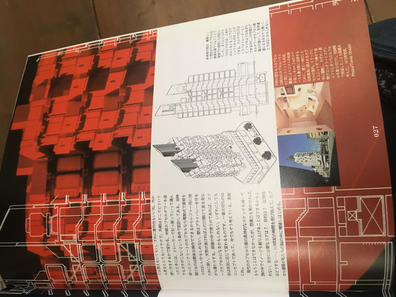

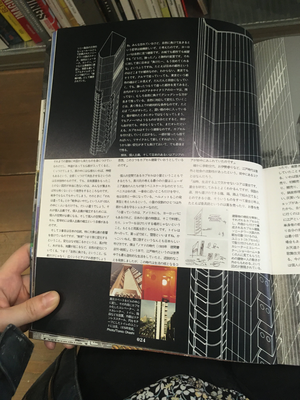

Then on, the shelter is reinforced and the core of the life that was outside enters the house... Mr. Kurokawa has the experience of driving around Japan in a Jeep and a trailer for a Jeep with a kitchen, bathroom, and toilet that he designed. The idea of the nomadic life is alive in one of his representative works, the Nakagin Capsule Tower. Each capsule is held with two bolts to the main pillar, and it can be taken out at any time. If you take out the capsule and load it on a trailer, you can move freely. Living in Ginza on the weekdays and going out for leisure dragging your home like a hermit crab was the resident figure Mr. Kurokawa imagined. In addition, when individuals become hermit crabs, they can move freely and gather freely to live. It connected to a proposal for a new lifestyle...

..."In the Nakagin Capsule Tower there are things called capsule tailers. Writers and critics use it to write. Or a company in Osaka uses it as accommodation in Tokyo. Everyone has the desire to be alone. Even if you have a house, you might want to rest on your way home from work, or study, or nap, it is convenient to have one in the city center"...

..."The capsule I am thinking of is that you can change it freely, so it is up to the resident on how they want to arrange the inside...When I made the Nakagin Capsule Tower, I designed it so it is strong enough to withstand being pulled by a trailer. The concrete capsule I used is electrically powered and opening the roof is easy so it might be good to use for leisure. The walls for protecting the privacy, and when it's a clear sky, opening the top to watch the stars and sleep. If you use it inside a room, it might become a sleep capsule. Either way the shape changes with the situation. The most important thing is the concept, and I still think so. Flexibility."...

translation:

Wanting to be the "person of wilderness," I head to the field

but it is past the time of stepping into the unknown wilds

and the "person of wilderness" cannot be completely alone.

Even if in the company of machines or animals,

complete solitude is impossible.

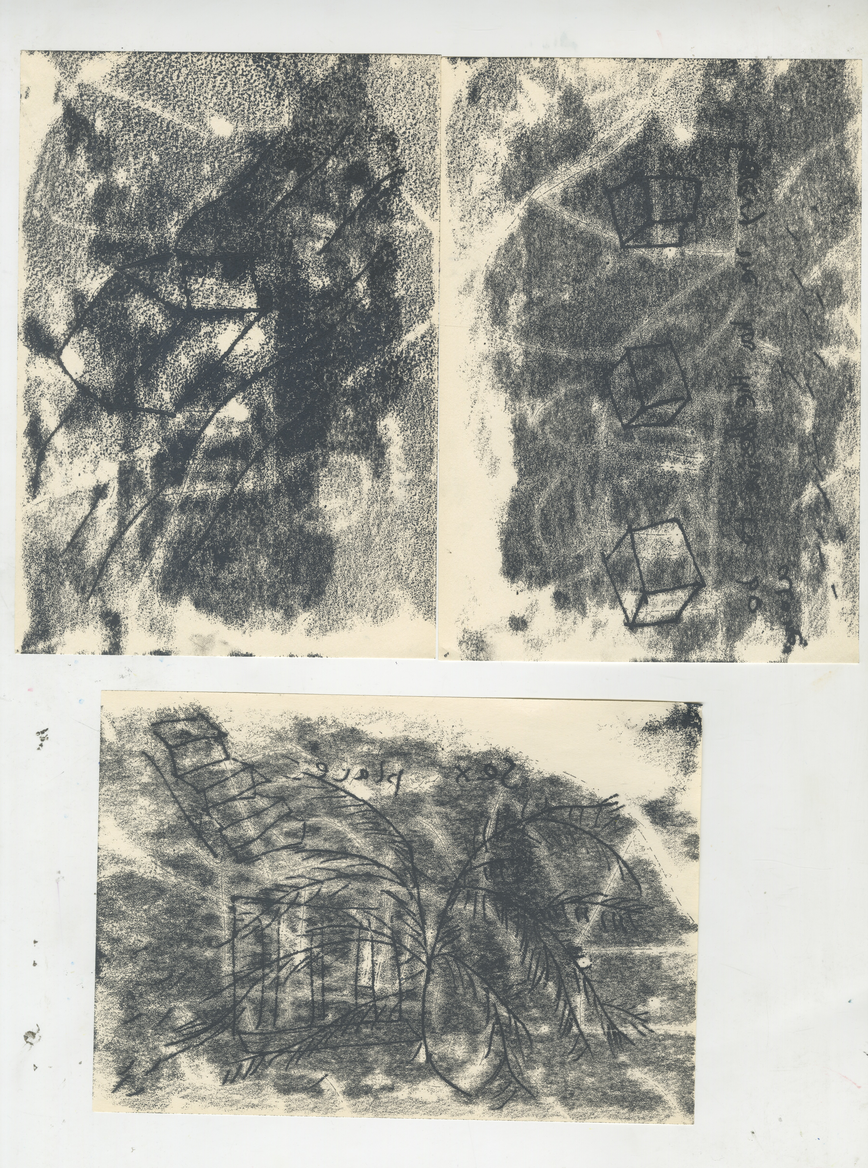

From then on, 小屋 became a container where the "person of wilderness"

can be dreamt of for a brief moment.

the 小屋 displays its power in the want for the impossible solitude

Making the fantasized 小屋 appear, and become pregnant with dreams in the closed space.

The shape of the 小屋 at the end of cocooning,

heads to a spread, or would it shrink?

As the era acceleratingly becomes more complex

the polarity of city vs. nature increases and

the shape of the 小屋 continues to work as the device of the dream.

It aims at a more radical shape and

bonds us to the dream.

That is why the 小屋 does not lose power.

It protects us anywhere in the world and pushes us to live.

Notes:

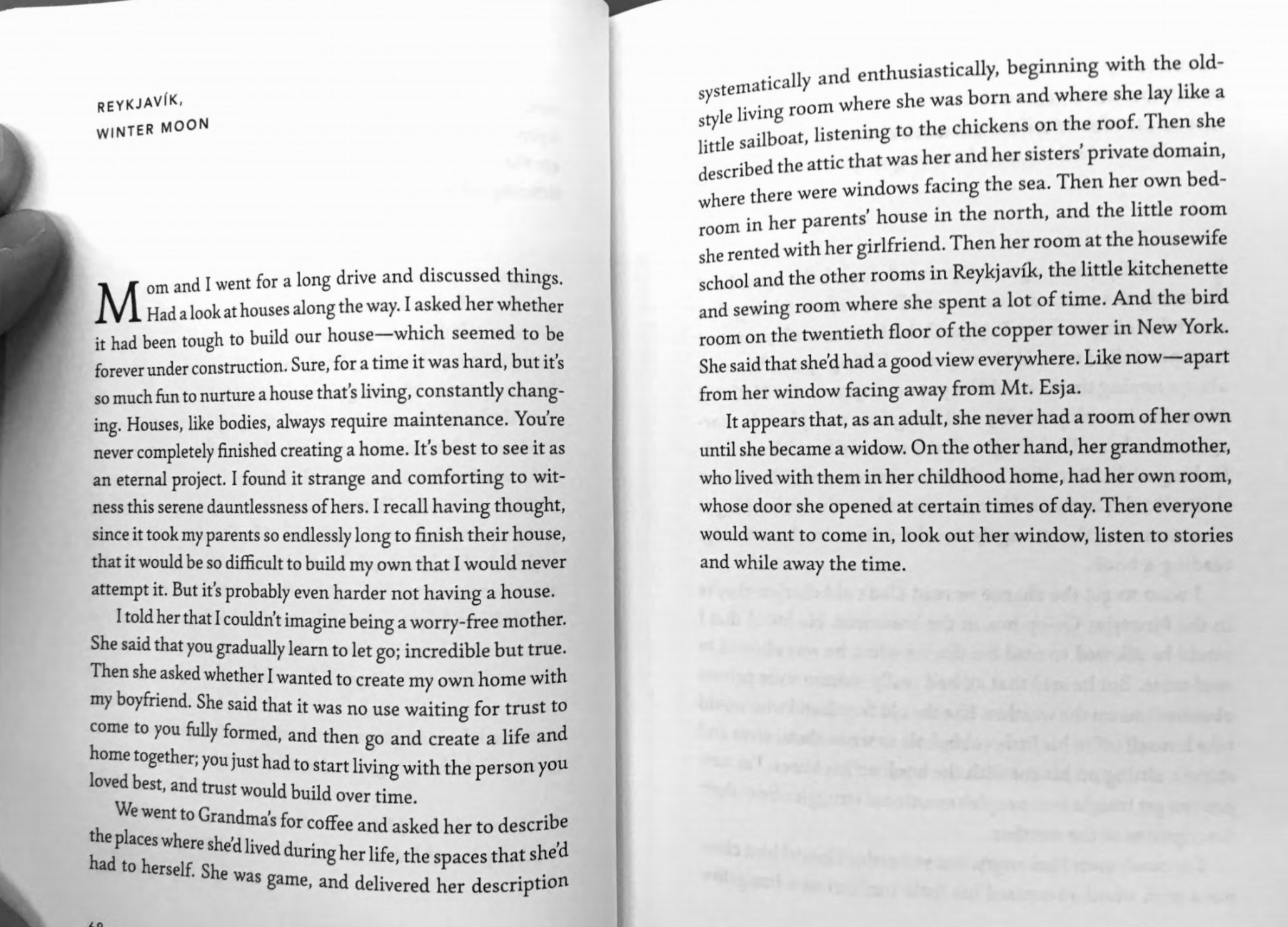

- Why must I situate my body within the construction of poetics? If the passage between traumatic silence and poetic silence could be named, it might be in this question.

- It was under the hazy sun, in the dimness similar to sleep. This was what I had called the edge, upon my arrival. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1xWglQ14bx7qMEV_ZC-exToZzGEXfwDM5YHJBVMdcnik/edit?usp=sharing

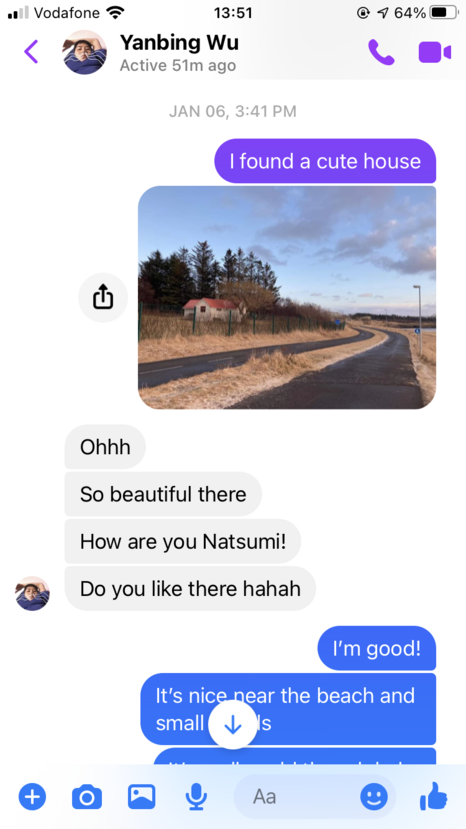

- I had come to Djúpavík, with the faint hope that it was possible to live in the middle of nowhere. It was indeed one of the happiest moments in my life, to distance myself from society to that extent. Perhaps it was only possible because it was a two-week stay.

- When I returned to the Netherlands and had two therapy sessions with a psychologist, I was pointed out my mistrust towards society and the possibility that it comes from my upbringing.

- I liked Djúpavík because of the slight hint of escape from the clasps of narrative that it gave. Narrative means society, it means being woven into the network. There is no reason for me to trust society or want to contribute to it. I dream of the buffer zone of poetics because the demands of reality in regard to social life are too uncomfortable.

- But maybe I can be ‘treated.’ I need to, anyway, if I am to find comfort in economic activity, which essentially means social activity. (Or else, I cannot convince myself that work is a positive thing.)

- And then, if the need for poetics were to remain, what is it? Or, is it that trauma is inherent in life and some amount of resistance towards society will never die out?

- And then, it was already disgusting when I meant someone from Djúpavík, once again in Reykjavík.