My central concern in this exposition is to appropriate the function of listening and our ability to tune in as a challenge to the specific given order in which we experience the world, or more specifically, in relation to what philosopher Jacques Rancière designates as ‘the distribution of the sensible’ (2006: 85). Rancière uses ‘the distribution of the sensible’ in an attempt to capture our collective environment, its contents, people, and places so as to describe how they are rendered seemingly stable and known. According to Rancière, what gets divided and how is determined by a pre-established mode of perception, a sensible order, based on what is deemed visible and audible. In addition to this, Rancière also includes what can be ‘said, thought, made, or done’ (2006: 85). In cultivating attention towards aural attention, I argue that our focus can fall on what can be made audible that would otherwise lie outside the ‘distribution of the sensible’. The main essence of my enquiry is foregrounded in sound’s potential to take us away from, and beyond, apparent given stability, an approach in accordance with Maurice Blanchot’s concept of literature, whose aim is ‘to interrupt the purposeful steps we are always taking toward a deeper understanding and surer grasp on things’ (Blanchot 1982: 3 cited in Shapiro 2013: xv).

I am interested in how a motivated phenomenology, as necessarily affective, might enable us to experience the world in a different order, thereby purporting distinct sensible modes of being. Accordingly, throughout this exposition, I re-interpret comparative literature scholar Rei Terada’s concept of the figure of the phenomenophile and phenomenophilia as invitations to develop works that both in their object format and in their documentation enable the investigation of aural attention. In Looking Away (2009), Terada develops the ‘phenomenophile’ (ibid.: 18) to describe a figure who prefers to look away at the coloured shadow on the wall, or who wishes to linger longer in looking, exhausting the semantic value of what is seen. In re-visiting debates on appearance and reality, Terada highlights the difficulties of dealing with ‘the given’. By suggesting a phenomenophilic mode of being that promulgates a sense of lingering in perception, Terada seeks to avoid acceptance of the world ‘as is’. She posits the possibility of ‘looking away’ as an alternative to the coercive imposition to know and to classify. In doing so Terada challenges Kantian aesthetic ideals. According to Terada, in the Critique of Judgement, fleeting and undefined perceptive encounters do not feature as they do not uphold the singular ideals of commonality and beauty. To counter this Terada indicates the appeal of perceptions that cannot be shared, and therefore also not appropriated. In Terada’s description, persistent looking stems from dissatisfaction with the classificatory nature of the world, highlighting a reluctance to endorse what is perceived in words. The act of phenomenophilia and Terada’s figure, ‘the phenomenophile’, promulgate an experience outside what is directly available, using selective inattention such as a look away to avoid what lies directly in front or what is made directly accessible. Though Terada’s discussion of the term is framed in relation to Coleridge’s preoccupation with phenomenal spectra (2009: 6), I adopt her term and apply it both critically and practically throughout the exposition. I propose the figure of the phenomenophile as key to thinking through the structure of sonorous relations, as such a strategy purports a counter-aesthetic and, by engaging the imagination, suggests the possibility of ‘doing things differently’ from the prescribed norm (ibid.: 8).

In attempting to articulate and draw attention to that which is just beyond reach of our perceptive capabilities, or what audio theorist Steve Goodman describes as the ‘not yet audible’ (2010: xvi), by practising and writing through instances of aural attention I aim to make tangible that which might be at work in the production, transmission, and mutation of affective tonality. My enquiry pursues examples of such occurrences taking place even at a micro-level. As philosopher Michel Serres states, ‘practically all matter, particularly flesh, vibrates and conducts sound’ (2008: 47). I adopt a critical agential position that locates a horizontal understanding between human and non-human relations. I make use of political theorist Jane Bennett’s argument in Vibrant Matter (2010) that agency is located in all matter. Expounding a Deleuzian-inspired sense of horizontality across all beings and things, Bennett defines life as ‘an interstitial field of non-personal, ahuman forces, flows, tendencies, and trajectories’ (ibid.: 61). Though Bennett’s argument, as she herself admits, overemphasizes the active powers issuing form to non-subjects to an extent that almost begins to marginalize human agency, she is able to highlight ‘what is typically cast in the shadow: the material agency or effectivity of nonhumans or not-quite-human things’ (ibid.: ix). For my own purposes within this investigation, instead of considering such relations as equally contributing agentic forces, I contemplate how affective forces residing in seemingly inert matter, e.g. objects or things, when turned towards, through either a physical positioning of the body, or by adopting an attitude that allows itself to be disorientated from habitual forms, a state of mutual attunement can be reached.

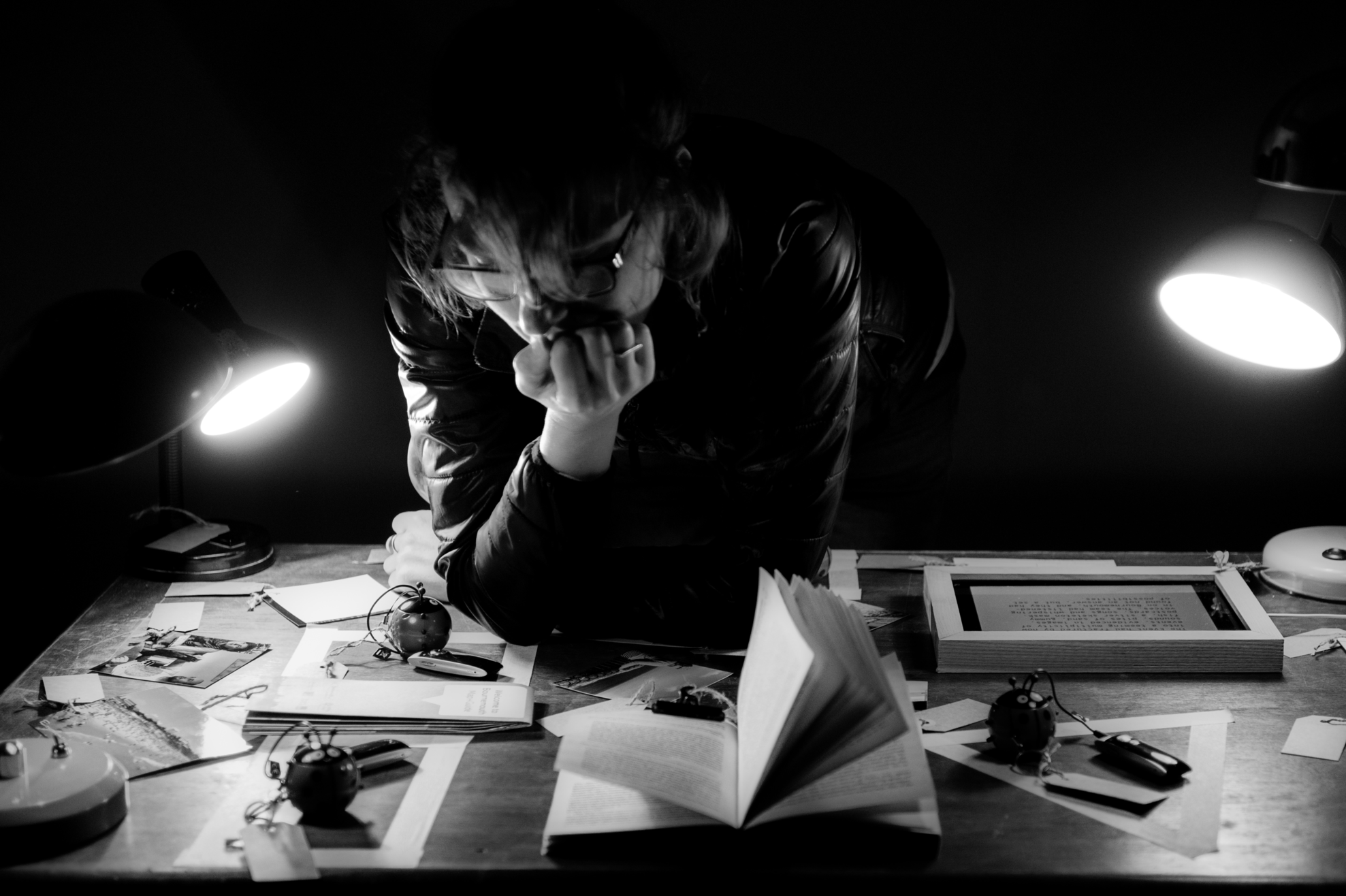

By experimenting with distinct writing registers I aim to draw the reader in close, encouraging them to linger longer within the pages of this exposition, extending the moment of perception as attention is suspended allowing interpretation to deploy itself in multiple dimensions, principally between the process of developing the work and encounters as gallery-goer / itinerant artist with a view to ultimately develop an understanding of sonorous relations.