I move the rough-edge of the plastic tube to my mouth and whisper something about the dark. I move it back to my ear and hear someone asking if I am alright repeatedly. Someone else answers over my words. I send out a ‘help me’ request in a voice slightly higher pitched than usual and receive what sounds like a national railway announcement in return.

A low hum […] mmmmmhhh, a low hummmmmmmh.

I give up trying to communicate or to speak to anyone. I feel the tube vibrate, I draw my mouth close adding my own voice to the vibrations.

The voices grow in volume, the pitch alters to accommodate my sound.

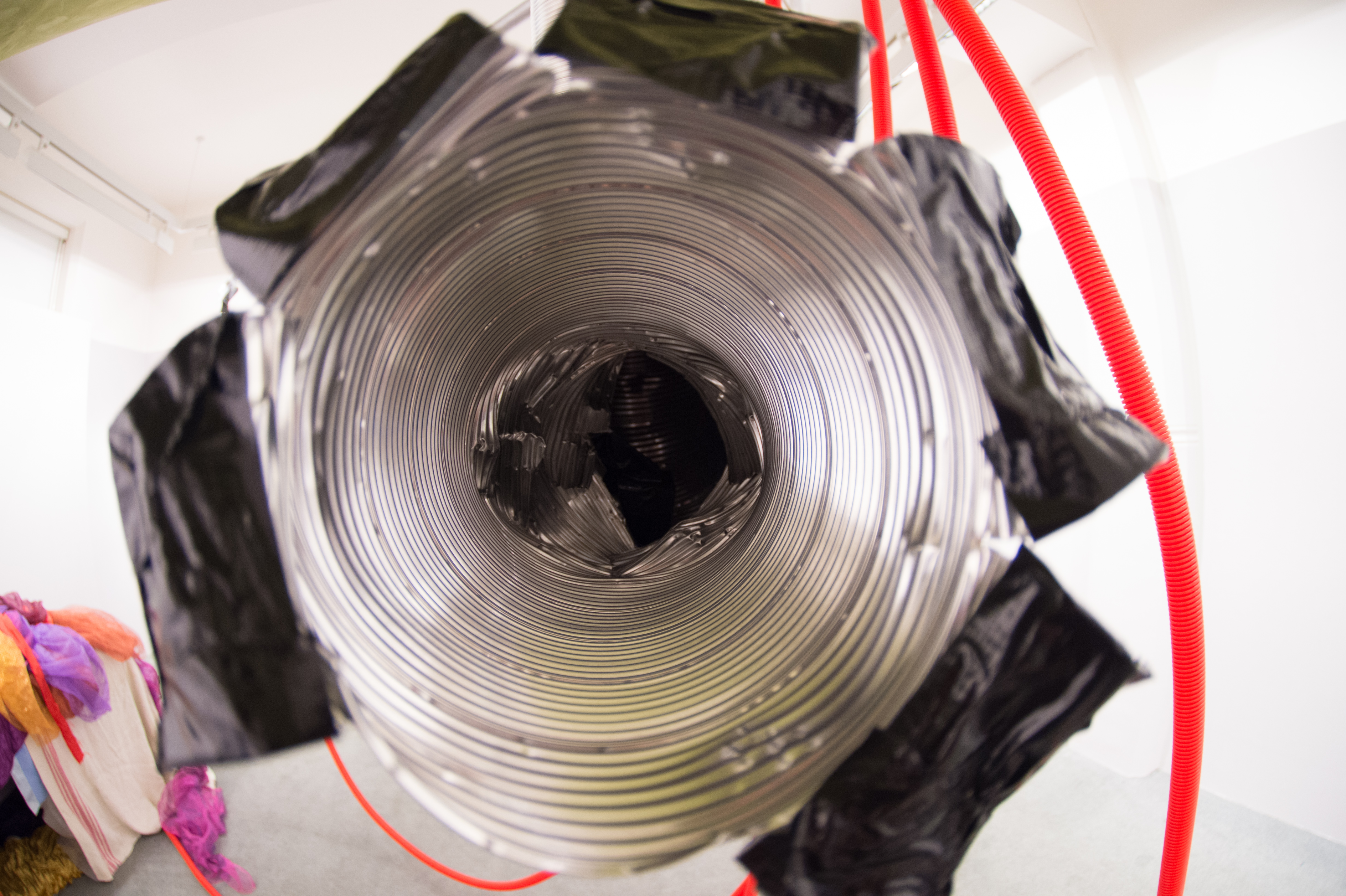

The hum grows and alters; it carves a shifting relational landscape between us, covering areas we can negotiate together without a pre-agreed trajectory to follow. It is ‘no longer a question of intercepting a sound and decoding or interpreting it, but rather of responding to a unique voice that signifies nothing but itself’ (Cavarero 2005: 7). We join together in sound, in what Philosopher Adriana Cavarero describes as ‘the maintenance of a relation that communicates no other meaning than the relation itself’ (ibid.: 195). There is no intention to communicate or to make sense. We are not only connected through sound but also via the red-ribbed plastic tube vibrating in our hands. We are a shifting sonorous landscape that puts us in common outside the voicing of language verging on ‘dangerously bodily, if not seductive or quasi-animal’ (ibid.: 13). A space for being opens, a space for vocal theatre that as soon as the mouth closes, is gone.