Above: a drawing of portage crossings leading to Mesa Lake in the Tłı̨chǫ, region by elder Edward Camille.

Illustrations from the land

After the excursion into the bush, youth from the community participated in an image-making workshop consisting of watercolour and collage activities using materials found on the land. Young participants interpreted Tłı̨chǫ landscapes, and represented moments from the story of Whanikw'o (Ruiz 2013: 64). Participants were encouraged to apply collage techniques – an approach that, historically, rejected stable materials and the ‘mystified act of painting’ in favour of ‘cutting, placing, and gluing’ impermanent materials (Antliff and Leighton 2001: 160). Unlike the cubist practice of collage, however, youth in this workshop made use of leaves, pinecones, twigs, and other material found on the land instead of mass-produced printed components.

During an initial demo showing this technique, participants were also introduced to rudimentary forms of printmaking using the veiny side of leaves. The combined use of land-based materials and watercolour as illustration media provided a new context and approach through which to communicate this traditional narrative. This hands-on image-making session offered a range of tools for visualising cultural knowledge by making use of material derived from the Tłı̨chǫ terrain.

The story of Whanikw'o: The Woman Who Came Back

Whanikw'o: The Woman Who Came Back is an oral story that tells of the first Tłı̨chǫ to make contact with Europeans in the late eighteenth century. The presence of this historic individual is documented by English explorer Samuel Hearne – in his 1772 journal he refers to an encounter with a Tłı̨chǫ woman who shared information that coincides with oral versions of the event (Scott 2012: 236).

Events conveyed through the narrative include the woman’s successful escape from subjugation and her contact with a European trading post. Her historical importance revolves around the new knowledge and technology that she brought back to her home region, as well as her possession of the Tłı̨chǫ notion of dǫ edàezhe, which translates to ‘a person who is capable, skillful and knowledgeable: a person who has the skills needed to survive in the world in the traditional Dene sense’ (Lafferty 2012: 217).

She has been referred to as Whanikw'o, as John B. Zoe and the late Jimmy Martin have indicated. Her resilience, along with her skills and knowledge that are adaptable to the Dene and Euro-Canadian world, make her a highly respected figure, embodying the Tłı̨chǫ educational philosophy of being strong like two people. Her story conveys a bicultural experience and captures a key moment in Tłı̨chǫ history when the presence of Europeans transformed the north.

Maintained within the context of regional storytelling practice for almost two centuries, Whanikw'o’s journey has only recently been recorded and translated. In Talking Tools, Patrick Scott (2012) includes three versions of the story, including one documented as part of a traditional knowledge project in March 2000, along with a version recorded by anthropologist June Helm and told by the late Vital Thomas in 1966.

As part of the research described in this exposition, five versions of the story were recorded in April and July 2012 – these were told by elders Melanie Lafferty, Liza MacKenzie, Monique MacKenzie, Robert MacKenzie, Rosalie Mantla, Elizabeth Rabesca, and Francis Willah (Ruiz 2013). Although details varied from story to story, the basic succession of events and overall theme conveyed through each version remained consistent throughout this project.

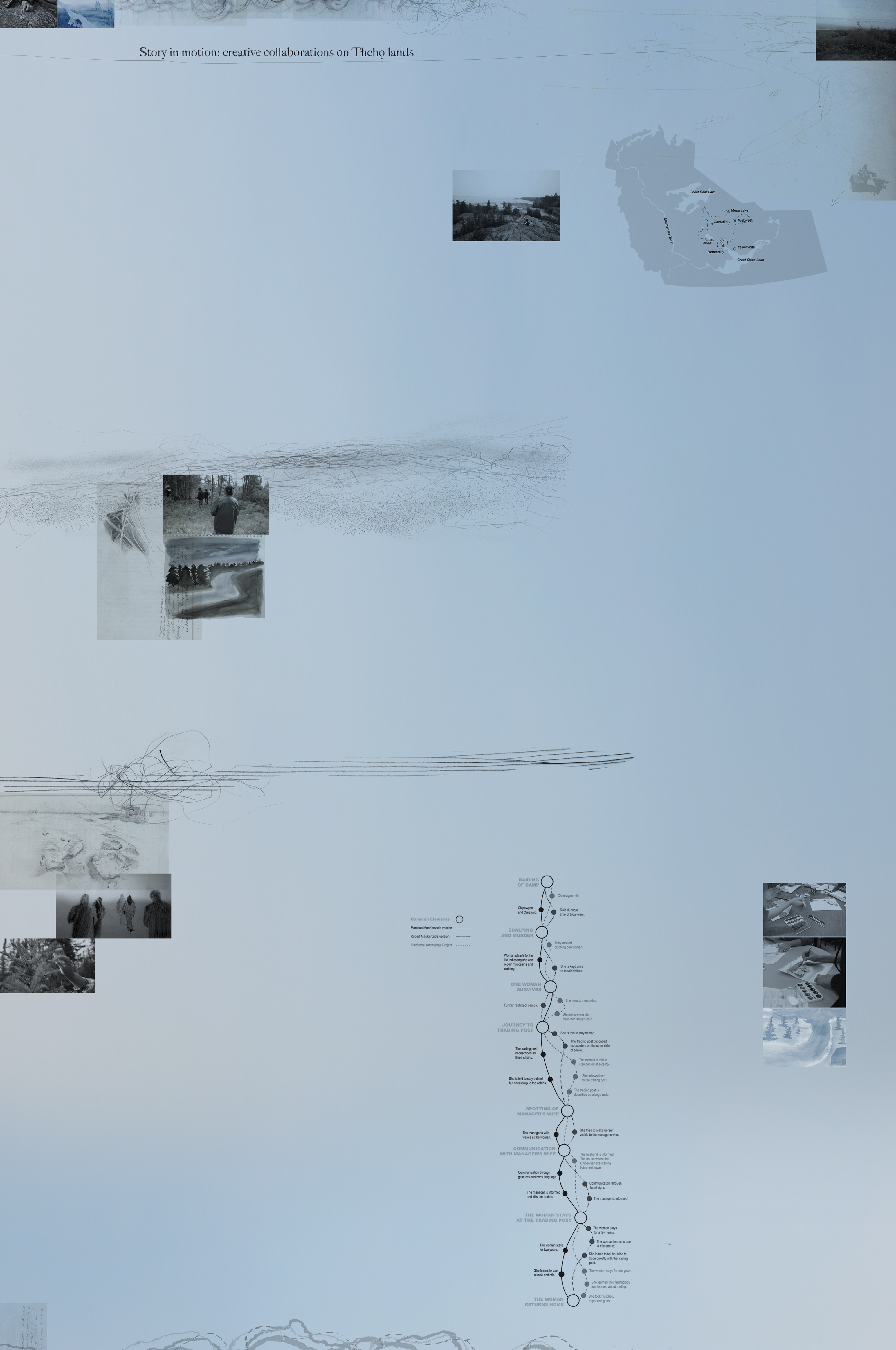

To visualise the range of similarities and differences between versions of the story we present a diagram that illustrates the points in the narrative where events diverge and coincide. This diagram (on the right) shows similarities and differences between three oral versions of Whanikw'o: The Woman Who Came Back (covering events from the raiding of the camp, at the start of the story, to the protagonist’s return home). As indicated in this diagram, the common elements across the many versions of the story consist of eight key events: 1) the story beginning with the raiding of a Tłı̨chǫ camp; 2) the scalping and murder of people in the camp; 3) the survival of one woman who is kept alive to repair clothing; 4) the woman’s journey, with the captors, to a trading post; 5) the woman spotting the trading-post manager’s wife inside a house; 6) the woman conveying her situation to the manager; 7) the woman staying at the trading post, where she learns of new technology; 8) the woman’s return home (Ruiz 2013; Scott 2012).

Events from this story were shared during a visit to Behchokǫ̀ on 23 April 2012 (all research during this visit took place in and around Chief Jimmy Bruneau High School in Behchokǫ̀). This storytelling session was initiated by elder Robert MacKenzie. He talked about the time of tribal wars – the world in which Whanikw'o lived (Ruiz 2013: 17). During the rest of the morning, three versions of the story were shared with rotating groups of students. Elders took turns being the primary storyteller. Usually, additional knowledge was filled in at the end of a session. This filling in of knowledge by another elder often involved additional information about the traditional way of life and technology that existed at the time of this story.

Following the storytelling sessions, Behchokǫ̀ youth participated in the revitalisation of the narrative through image-making workshops (24–27 April 2012). Thirty-six students from grades ten, eleven, and twelve participated in this part of the research – visualising landscapes and events from the story shared by elders (Ruiz 2013).

All landscapes depicted in the final animated version of the story, including trees, hills, and sky and water textures, were produced by students. The idea of providing students with the opportunity to be active participants and contributors to this project is derived from IRM, as well as Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy. Through his work, Freire (2007: 86) aimed to resolve the teacher–student dichotomy by involving students in the learning experience as ‘critical co-investigators in dialogue with the teacher’.

The image-making component of this workshop provided creative tools through which young people contributed to the translation of a regional oral story into animation. The notion of being strong like two people was addressed throughout the week when describing the importance of elders working with youth, and also when explaining how this project aimed to merge traditional knowledge with design and animation media.

Drawing lines

The journey of Whanikw'o, shared by elders in Behchokǫ̀ illustrates the fundamental role of walking in traditional Tłı̨chǫ society. As described in this and other oral stories, the act of walking was an essential part of traditional life that produced ‘visible . . . well-worn footpaths’ throughout the Tłı̨chǫ region (Andrews 2011: 37). Today, footpaths and trails remain visible across the land, as physical evidence of how previous generations ‘walked almost everywhere in all seasons’ (29).

The image of a vast geographic area made up of ‘interlaced trails’ or ‘entangled lines’ embodies the traditional practice of travelling and acquiring knowledge on the land (Ingold 2011: 71). Using drawing as a methodology, the first author attempted to reflect on Whanikw'o’s journey, and the enduring trails embedded in the land, through repetitive gestural hand movements. Thousands of sketches, rendered by hand, were brought together and used to visualise the story of The Woman Who Came Back in the form of an animated film. Like the Dene wayfarer, whose walking is ‘rhythmic and repetitive’ but constantly adapting to the flux of the surrounding environment, the repeated execution of drawn material requires manual gesture with continual corrections and adjustments to an evolving story world (Ingold 2011: 53). The drawings were made on transparent sheets, and are at times sketchy and imperfect, revealing eraser marks and damages to the paper surface. Collectively, these drawings tell a story, but also reveal the evolving relation and tension between ‘practitioner, tool, and material’ (ibid.: 58). As David Pye has stated, there is ‘continuous attention and correction’ involved in working with hand-held tools (quoted in ibid.: 58). Through this research, the use of traditional drawing media (as opposed to the exclusive use of computer-generated graphics), was considered an appropriate embodiment of an oral story that reveals human movement, the use of manual tools, and adaptation to a changing environment.

Presenting these sketches in a time-based context reveals a sense of movement that is often initiated by lines that appear and disappear against changing background imagery. Twenty-four drawings were made for every second of character movement as the protagonist of the story is shown walking through Tłı̨chǫ landscapes painted by Behchokǫ̀ youth. Reflecting one of the concerns of this project – that of narrative revitalisation – this film often makes formal reference to the methods of ‘early animations’ from the first decade of the 1900s, in which ‘giving life to things’ through the drawing of lines was an essential aspect of this emerging art form (Telotte 2010: 29). In one of the earliest examples of traditional, hand-drawn animations (Emile Cohl’s Fantasmagorie, 1908), the work reveals how ‘a single point or line can quite literally become the starting point for all sorts of new . . . images’ (Telotte 2010: 28).

In contemplating Arctic culture, Rudy Wiebe writes that ‘as soon as a person moves he or she becomes a line. People are known and recognized by the trails they leave behind’ (1989: 15). Tim Ingold (2011) describes ‘the texture of the lifeworld’ (70) as a ‘meshwork of entangled lines of life, growth and movement’ (63). Similarly, the texture of an animated story world, made using a traditional, frame-by-frame technique points to what Telotte (2010) refers to as the ‘governing principle’ of ‘the line’ (31) and ‘the power of transformation’ (27).

In saying that ‘drawing is fundamental to being human,’ Ingold refers not only to mark-making on paper, but also to walking and human gestures that ‘leave traces or trails, on the ground or some other surface’ (2011: 177). It is this expanded notion of linework that is central to Ingold’s writings, Tłı̨chǫ ways of knowing, and traditional hand-drawn animation.

Research on the land

Later that year (in July 2012), a two-day on-the-land workshop was organised. During this event, elders shared further information about the story of Whanikw'o. This event provided another opportunity for youth from the community to participate in storytelling and image-making activities. The first author travelled to Behchokǫ̀ in early July. Upon arrival he met with the second author to organise the schedule for the workshop, which was to begin with the setting up of camp at Russell Lake, about 5 km from Behchokǫ̀ (Ruiz 2013: 61).

The following day, most of the time was spent in a large tent near the lake where storytelling sessions took place. After elders covered the floor area with spruce boughs, we entered and sat inside the tent (the following were in attendance: elders Robert MacKenzie, Liza MacKenzie, and Monique MacKenzie, along with Tony Rabesca and community youth) (Ruiz 2013: 61). After an opening ceremony, another version of the story was shared by Monique MacKenzie (Ruiz 2013: 62). This storytelling session provided further information about Whanikw'o.

The next day, a walk into the bush complemented this narrative research by exploring the journey of Whanikw'o through the eyes of elders. Guiding us into a forest area near the Russell Lake camp, elders described traditional knowledge that Whanikw'o could have used in the 1700s. Hands-on demonstrations included the use of a traditional trap for catching small game (see left image) – this knowledge was recorded, subsequently animated, and used in the film (Ruiz 2013: 62).

Elders also described how the light, soft wood from balsam poplar trees was used as a tool. Liza MacKenzie provided a brief explanation of a traditional approach combining the use of this wood and caribou bone to scrape animal hide (Ruiz 2013: 63). Explorations of traditional knowledge during day two of this workshop were reflective of how ‘Tłı̨chǫ culture is tied directly to the landscape’ (Andrews and Zoe 2007: 23). During this part of the research, material located in the forest area near the camp elicited knowledge of tools, traps, and memories of life on the land.

This excursion into the bush expanded the narrative-based research with elders − from oral storytelling to geographical explorations. Walking and talking on the land generated further knowledge to be included in the animated film. Working with members of the Behchokǫ̀ community in a meaningful geographical context provided an opportunity for information to emerge through a process of travelling by foot. Knowledge gathered in this part of the research produced further insight into Tłı̨chǫ oral history through conversations on the land.

Hybrid animation

The production of Whanikw'o: The Woman Who Came Back animation involved three key steps: the illustrated work of student participants (as described above), the technique of rotoscoping to create character movement, and the use of Adobe After Effects to edit the film. This eclectic combination of methods reflects the merging of traditional and contemporary knowledge (an important theme in this research). Through the production of this film, traditional, hand-generated illustrations were contextualised within a digital story world.

Artwork produced by participants consisted of illustrations of Tłı̨chǫ landscapes using watercolour and collage. All landscapes shown in the film were made using images created by young participants from Behchokǫ̀. Within the animation, landscapes are separate layers behind human figures – a rotoscoping technique was used to bring human figures to life.

Rotoscoping is described by J. P. Telotte (2010: 17) as a form of ‘hybrid animation’ involving the manual tracing of recorded live-action movement. To animate character movement in Whanikw'o: The Woman Who Came Back, the first author began by recording live-action footage of actress Reneltta Arluk (who interpreted Whanikw'o’s gestures, walking, and tool-use) (Ruiz 2013: 80). Footage of Reneltta Arluk was then exported in a computer as JPEG frames (24 per second). Afterwards, each frame was manually rendered by drawing over a sheet of tracing paper (placed over the computer screen). Once traced, further coverage with Prismacolor markers, graphite, and at times pencil crayons was used to add detail, texture, and volume to each drawing.6

The results of this technique, involving the tracing of movement, rendering of form, and subsequent photographing of each image, provided a sense of figure motion that is realistic. The choice of using a realistic approach is based on references by Behchokǫ̀ elders to the truthful nature of the story of Whanikw'o. Elders referred to this narrative as history.7

Following the frame-by-frame rendering, student artwork and rotoscoped footage were brought together and configured in Adobe After Effects. This program was used for its ability to animate layers of rasterised imagery, and the availability of a camera and light tool that facilitates the rendering of environments that appear to be three-dimensional. The positioning of the camera tool at different points, and using varying focal distances on the After Effects timeline, also allowed for the creation of footage in which the viewer appears to enter and travel through the illustrated landscape. The final edit of the film was executed in Adobe Premiere, where the latest movie and sound files were merged. The audio primarily consisted of a spoken narration along with traditional drumming and singing recorded during the July culture camp.

Introduction and research methods

This exposition revolves around a creative collaboration in the Tłı̨chǫ region of Canada’s Northwest Territories. Since 2012 the authors of this paper have worked with elders, youth, and government workers in projects that involve the visualisation of oral history through moving image production.1 This exposition describes our first collaboration.2

In presenting this co-authored exposition, we recognise this work as a rich and humbling learning experience, made possible through the hospitality and friendship of people in the Northwest Territories. The support of community members and scholars whose work involves the revitalisation of Dene cultural knowledge has also made this work possible. The most notable community members who participated in this work are Tłı̨chǫ elders who are acknowledged in this exposition. The impetus and inspiration for this project also comes from Gavin Renwick (former Canada Research Chair for Design Studies) and Patrick Scott, whose research in Dene storytelling informs this project. These individuals facilitated knowledge and guidance throughout this research. Gavin Renwick and Patrick Scott also share a common approach to working with communities. This approach involves respect, sensitivity, and the integration of cultural protocols within research – in short, Indigenous research methods (IRM).

IRM is a qualitative method that is built on relationships, and grows from respectful adherence to cultural protocols, while creating positive change for members of a community (Absolon and Willett 2005; Kovach 2005; Smith 1999; Wilson 2008). The relationship between researcher and community members is foundational to this method.

Through IRM, researchers situate themselves within the context of their inquiry – this is an important first step in the relationship-building process (Absolon and Willett 2005). This first reflexive step also helps build awareness of cultural assumptions while shedding light on the socio-historical locations that shape an investigation.

Through this opening section, we acknowledge our place within this project – the first author is a non-Indigenous researcher/film-maker, and the second author is a Tłı̨chǫ citizen working as cultural practices manager for the regional government. The first author shares a brief positionality statement to further describe location in relation to this research.3

Ongoing dialogue has also been essential to the development of this

research – allowing for a respectful approach to community activities and bringing together a diverse range of contributions. Ideas and imagery shared in this exposition are the product of an intercultural collaboration – combining, among other things, oral history shared by elders, artwork generated by youth, along with skills in knowledge translation that the first author facilitated through participatory approaches to art practice.

The Tłı̨chǫ educational philosophy of being strong like two people has also informed this research. Being strong like two refers to educational experiences that combine two ways of knowing (Zoe 2007). Throughout this exposition we will further reference the significance of this philosophy.4

References

Absolon, Kathy, and Cam Willett. 2005. ‘Putting Ourselves Forward: Location in Aboriginal

Research’, in Leslie Brown and Susan Strega (eds), Research as Resistance: Critical, Indigenous, and Anti-oppressive Approaches (Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press/Womens’ Press), pp. 97–126

Afonso, Ana Isabel, and Manuel João Ramos. 2004. ‘New Graphics for Old Stories: Representation of Local Memories through Drawings’, in Sarah Pink, László Kürti, and Ana Isabel Afonso (eds.), Working Images: Visual Research and Representation in Anthropology (London: Routledge), pp. 72–89

Andrews, Thomas D. 2011. ‘“There Will Be Many Stories”: Museum Anthropology, Collaboration, and the Tłı̨chǫ’ (unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Dundee) <https://discovery.dundee.ac.uk/en/studentTheses/there-will-be-many-stories> [accessed 3 March 2023]

Andrew, Thomas D., and Zoe John B. 2007. ‘Trails: Archaeology and the Tłı̨chǫ Cultural Landscape’, in John B. Zoe (ed.), Trails of our Ancestors: Building a Nation (Behchokǫ: Tłı̨chǫ Government), pp. 20-28

Antliff, Mark, and Patricia Leighten. 2001. Cubism and Culture (London: Thames & Hudson)

Antoine, Asma-na-hi, and others. 2018. Pulling Together: A Guide for Curriculum Developers (Victoria, BC: BCcampus) <https://opentextbc.ca/indigenizationcurriculumdevelopers/> [accessed 3 March 2023]

Archer, Bruce. 1995. ‘The Nature of Research’, Co-design: Interdisciplinary Journal of Design (January): 6–13

Archibald, Jo-ann, Jenny Lee-Morgan, and Jason De Santolo. 2019. Decolonizing Research: Indigenous Storywork as Methodology (London: Zed Books)

Coulthard, Glen Sean. 2014. Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press)

Freire, Paulo. 2007. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, trans. by Myra Bergman Ramos, 30th anniversary edn (New York: Continuum)

Ingold, Tim. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description (Abingdon, UK: Routledge)

Jacobs, Donald Trent. 2008. The Authentic Dissertation: Alternative Ways of Knowing, Research and Representation (Abingdon, UK: Routledge)

Kovach, Margaret. 2005. ‘Emerging from the Margins: Indigenous Methodologies’, in Leslie Brown and Susan Strega (eds), Research as Resistance: Critical, Indigenous, and Anti-oppressive Approaches (Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press/Womens’ Press), pp. 19–36

Lafferty, Dianne. 2012. ‘Dǫ edàezhe: Building Resiliency among Aboriginal Youth’, Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health, 10.2: 217–30

Manzini, Ezio. 2016. ‘Design and Dialogic Culture’, Design Issues, 32.1: 52–59

National Film Board of Canada. 2017. ‘Indigenous Filmmaking at the NFB: An Overview’ <https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/nfb-onf/documents/pdfs/plans-action-autochtones/en/Backgrounder-NFB-IndigenousFilmmaking.pdf> [accessed 3 March 2023]

Conclusion

The final animated version of Whanikw'o: The Woman Who Came Back was initially screened in Behchokǫ̀, on 15 May 2013. This first screening was organised exclusively for the group of elders who shared versions of the story during research in 2012. Approval of the film by community elders was required before further screenings could take place in the community. As part of their post-screening feedback, elders shared additional oral versions of the story, and discussed the importance of connecting generations through research activities (Ruiz 2018: 139). This further sharing of the story acknowledges the animated version of Whanikw'o’s journey as one among many other oral versions of the narrative.

The value of this animated film primarily resides in its pedagogical potential – as a teaching tool for community members. The film is ‘communicable knowledge’ – used in cultural and educational contexts throughout the region (Archer 1995: 11). The value of this project also resides in community-based experiences and the intergenerational activities through which the story was shared and translated into moving pictures. The project described in this exposition offers an example of how elders and youth may work together in the visualisation of oral history. The methodology behind this research was carefully considered to provide community engagement and an outcome that was meaningful and valuable to the Tłı̨chǫ community.

Beyond the film, however, there are other, equally important results that developed through this project. Most importantly, the very process of making this film (through storytelling sessions, sharing of traditional knowledge, and intergenerational activities) helped strengthen relationships. The connection between elders and youth, as well as the first author’s relationship with community members, was strengthened through this research – the first author emphasised this important, intangible outcome of work on Tłı̨chǫ lands through PhD research (Ruiz 2018: 201).

As we conclude this exposition, we acknowledge the generosity of elders and other knowledge holders from the Tłı̨chǫ region. Their participation in this project helped situate regional oral history within the present. Knowledge holders from the region played a vital role in making Whanikw'o: The Woman Who Came Back a valuable pedagogical tool through which to discuss the ongoing significance of ancestral knowledge in contemporary Tłı̨chǫ society.

Revitalising oral tradition

Based in Behchokǫ̀ (the largest community in the Tłı̨chǫ region), the research discussed in this exposition revolves around the sharing and collective visualisation of an oral story (the story of Whanikw'o: The Woman Who Came Back). The process and knowledge generated through this research responds to the need for cultural revitalisation in the Tłı̨chǫ region as articulated by, among others, Patrick Scott, who has described the need to find tools that sustain oral tradition in Dene communities. For Scott, a ‘central issue has become how to ensure stories from the past will continue to color the present and shape the future’ (Scott 2012: 253). Developed through participatory design and animation, this research provides an alternative to the conventional ‘documenting, recording, and preserving’ of oral stories (225).

Storytelling by elders, along with creative contributions by youth, has provided a context in which a narrative was discussed, interpreted, and visualised during visits in 2012, and brought back to the community in the form of an animation in 2013.5 Sharing the outcome of this research with people in Behchokǫ̀ was essential to the overall process of collaborating and exchanging knowledge. In discussing the collaboration and material that emerged through this research, we will continue this exposition by providing an overview of Whanikw'o: The Woman Who Came Back (the oral story on which this research is based). We will then refer to the first storytelling and image-making workshop, in April 2012. Following this section, we will discuss the importance of the land in generating knowledge during this inquiry (involving an excursion led by elders, and outdoor image-making activities designed for youth). The final two sections of this exposition include a description of the animated production Whanikw'o: The Woman Who Came Back, and a final reflection on the role this film plays in regional educational contexts.

Right: Similarities and differences between three oral versions of Whanikw'o: The Woman Who Came Back.

Indigenous animation in Canada

This section provides a brief overview of Indigenous animated film production in Canada – focused on work from the Arctic and subarctic (the area where the Tłı̨chǫ region is located). Reference is also made, however, to contemporary artists from across the country. This overview helps contextualise the Tłı̨chǫ film described in this exposition within a history of animation production involving collaborative projects in the north. Participatory and Indigenous-led film production in Canada began in the late 1960s, through the National Film Board of Canada (NFB). One of the early directors from this time is Alanis Obomsawin (National Film Board of Canada 2017: 4).

There is also a history of collaborative animation production in Canada that revolves around regional stories. Initial collaborative works in the north took place from 1971 to 1975 between Inuit and non-Inuit artists (also initiated by the NFB). During this time, Inuit artists provided art direction, narration, sound design, music, and scripts for several short films, including Animation from Cape Dorset (1973), the first animated film created by Inuit artists. The film features the work of Solomonie Pootoogook, Timmun Alariaq, Mathew Joanasie, and Itee Pootoogook Pilaloosie (St-Pierre 2022).

The next major animated film partnership between the NFB and Inuit artists was the Nunavut Animation Lab. This project resulted in four films in 2010:

Qalualik (Ame Papatsie); Lumaajuuq (Alethea Arnaquq-Baril); The Bear Facts

(Jonathan Wright); and I Am But a Little Woman (Gyu Oh) (St-Pierre 2022). Beyond the north, and in recent years, Indigenous animation has also emerged outside the NFB, through the work of artists such as Skawennati, Christopher Auchter, Terri Calder, and Amanda Strong.

Projects referenced in this section were made using a range of animation techniques – including cut-outs, sand, stop-motion, photography, and digital compositing. In terms of content, the films depict oral history, traditional practices, memories of home, and lived experiences, as well as future-oriented themes. Films emerging from early NFB collaborations present a dynamic picture of home – where people, animals, and land coalesce in a web of relations. Many recent projects reveal similarly innovative methods of storytelling through rich visual language that combines land-based experiences and digital media.

1. Residing within a self-governed area (39,000 km2) in the Northwest Territories of Canada, the Tłı̨chǫ are a group of Athabaskan-speaking Dene people – see map on the right. The geography of the region consists of boreal forest as well as Precambrian rock and tundra in the north. Behchokǫ̀ is the largest community in the region (where all research discussed in this exposition took place).

2. Imagery and events presented in this exposition emerged through graduate research in the Department of Art and Design at the University of Alberta (Ruiz 2013).

3. As a member of the Euro-Canadian settler population in Canada, I situate myself by recognising the privilege I hold within intersecting institutional and cultural contexts. I also recognise the extent to which my worldview is shaped by Western epistemologies. Part of my ongoing work in the Tłı̨chǫ

region involves recognising the limitations of my cultural perspective while walking the land, listening, and learning through continuous dialogue.

4. In addition to IRM, this research is also based on what the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (2021) describes as research-creation. This type of research ‘combines creative and academic research practices’, supporting ‘the development of knowledge and innovation’ (ibid.). Scholarship from the field of design (specifically, design literature that discusses the role of participatory activity within research) has also informed this project. This scholarship includes the notion of ‘dialogic design’, as described by Ezio Manzini (2016: 58): ‘a social conversation in which everybody is allowed to bring ideas and take action’. Tools developed by Elizabeth Sanders (2006), who discusses the role of co-creation and collaboration within research, have also led to many of the approaches described in this exposition.

Community knowledge and production

The animated film presented in this exposition emerged from various sources of knowledge and creative production situated in Behchokǫ̀. As with the hybrid approach to the technical production of this project, multiple voices contributed to the making of Whanikw'o: The Woman Who Came Back. The inclusion of elders and youth – each making unique contributions to this project while often sharing the same space – reveals how participatory artistic practice can facilitate rich educational experiences in the teaching of regional oral history. This section provides a description of contributions provided by Behchokǫ̀ community members.

Tony Rabesca, the second author of this exposition, played a vital role throughout the production of this animated film – especially during the initial stages of community-based research. The two authors worked closely in planning and organising community-based workshops – Tony Rabesca’s knowledge of the community, its resources, and culture of the region made this project possible. Tony brought together knowledgeable elders (mentioned above) who shared multiple versions of the story on which the animated film is based. He also identified translators – James Rabesca, Mary Seimens, and Tammy Steindwand-Deschambeault – who played an important role in translating Tłı̨chǫ narratives to English during storytelling sessions.

Tony Rabesca also connected with staff at Chief Jimmy Bruneau High School in Behchokǫ̀ to engage art students in visualising landscapes from the story. The following students contributed artwork to the film: Blade Bishop, Shane Campbell, Nathan Drybones, Nathan Football, Andy Gon, Julian Gon, Candance Lafferty, Sharon Lafferty, Deanna Mantla, Dien Rabesca, Nathan Rabesca, Laina Steinwand, Courtney Wedzin, Nicole Wetrade, Noland Weyallon, Oliver Weyallon, Ketrick Whane, Rachel Yakenna, and Desmond Zoe.

In terms of the audio components of this project, Tony Rabesca’s singing and drumming serve as the soundtrack for the film. Rosa Mantla (language, culture coordinator) narrated the film presented in this exposition.

Ruiz, Adolfo. 2013. ‘Sharing Stories and Moving Pictures: Animating Oral History in the Tłı̨chǫ Region’ (unpublished master’s thesis, University of Alberta)

———. 2018. ‘Tracing Memories: Collaborative Research in the Tłı̨chǫ region’ (unpublished PhD dissertation, University of Alberta) <https://era.library.ualberta.ca/items/95c73a10-49cc-487b-9fbb-a75d9ff15133/view/1f472268-b558-4423-9772-adec44c0f7e5/Ruiz_Adolfo_201809_PhD.pdf> [accessed 2 March 2023]

———. 2022. ‘A Place We Call Home: Curriculum for Land-Based Education’, in Dan Lockton and others (eds.), DRS2022: Bilbao <https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2022.161> [accessed 3 March 2023]

Ryan, Joan. 1994. Traditional Dene Medicine Part One: Report (Lac La Martre, NT: Dene Cultural Institute)

Sanders, Elizabeth B.-N. 2006. ‘Scaffolds for Building Everyday Creativity’, in Jorge Frascara (ed.), Designing Effective Communications: Creating Contexts for Clarity and Meaning (New York: Allworth Press), pp. 65–77

Scott, Patrick. 2012. Talking Tools: Faces of Aboriginal Oral Tradition in Contemporary Society (Edmonton, AB: CCI Press)

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. 1999. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London: Zed Books)

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. 2021. ‘Definitions of Terms’, Government of Canada <https://www.sshrc-crsh.gc.ca/funding-financement/programs-programmes/definitions-eng.aspx#a22> [accessed 2 March 2023]

St-Pierre, Marc. 2022. ‘Inuit Cinema at the NFB | Curator’s Perspective’, NFB Blog, 25 March <https://blog.nfb.ca/blog/2022/03/25/inuit-cinema-at-the-nfb-curators-perspective/> [accessed 6 March 2023]

Telotte, J. P. 2010. Animating Space: From Mickey to Wall-E (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky)

Warner, Linda Sue, and Gerald E. Gipp. 2009. Tradition and Culture in the Millennium: Tribal Colleges and Universities (Charlotte, NC: Information Age)

Wiebe, Rudy. 1989. Playing Dead: A Contemplation Concerning the Arctic (Edmonton, AB: NeWest)

Wilson, Shawn. 2008. Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods (Halifax, NS: Fernwood)

Zoe, John B. 2007. ‘Trails of Our Ancestors: Building a Nation’, in John B. Zoe (ed.), Trails of Our Ancestors: Building a Nation (Behchokǫ̀, NT: Tłı̨chǫ Community Services Agency), pp. 97–126

Zoe, John B., Jim Martin, and Nancy Gibson. 2012. ‘The Story That Was in Danger of Being Left Behind: Restorying Tłı̨chǫ Culture with Land Claims and Self-Government; A Conversation with John B. Zoe’, Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health, 10.2: 149–50

5. It has been ten years since the start of this research and film production. This exposition provides an opportunity to reflect on the ongoing significance of Whanikw'o’s journey in contemporary Tłı̨chǫ society. More recent collaborations speak to the importance of this story or the value of traditional knowledge embodied by Whanikw'o (Ruiz 2018; Ruiz 2022).

Furthermore, as we discuss in the following sections, an important aspect of this research involved the very process of sharing stories in Behchokǫ̀. The creation of workshops through which oral history could be conveyed by elders provided opportunities for transmitting information to youth, while recontextualising a historical event in contemporary Tłı̨chǫ society.

The retelling of narratives is an important aspect of oral tradition through which stories continue to be a living part of a community. As Donald Trent Jacobs (2008: 2) writes, stories are ‘living information systems’.

Stories, however, are alive inasmuch as they continue to be shared by multiple knowledge holders – an idea expressed by Tłı̨chǫ elder Philip Zoe (quoted in Scott 2011: 140): ‘A Tłı̨chǫ story has many, many parts and no one person has the full story. To really know and use the story, and explore all of its meanings, you have to hear many versions and add your own parts.’

Elder Zoe’s insight is suggestive of an adaptable knowledge system – unlike the notion of history as a ‘totalizing discourse’ (Smith 1999: 30). According to Linda Tuhiwai Smith (ibid.: 30), ‘The idea that history can be told in one coherent narrative’ is a key characteristic of colonial ideology.

Left: The lakeside near Behchokǫ̀ (recorded by Scott Portingale during research in 2015).

Bottom left: time-lapse photography of Mesa Lake in the north of the Tłı̨chǫ region (by Scott Portingale in 2014), and a description of the use of resin from spruce trees by elder Monique Mackenzie (during the July 2012 workshop).

Demonstrations provided by elders during the July 2012 workshop were based on traditional ecological knowledge: ‘a body of knowledge built up . . . through generations of living in close contact with nature’ (Ryan 1994: 20). This understanding of the land revolves around a system of ethics that governs use of resources, as well as empirical observations, relationships of reciprocity, and systems of classification (ibid.).

Writing in 1994, anthropologist Joan Ryan indicated that (at the time) this knowledge continued to provide the basis for regional medicine. A holistic worldview is integral to this domain of expertise. As Joan Ryan (1994: 20) notes, this form of medicine is based on ‘understanding that the parts of the natural world all have their own life force, are interconnected and flow in cycles of birth and rebirth’.

6. A makeshift animation stand was created to photograph each illustrated image. A Canon Rebel XSi camera (approximately 140 cm off the ground) was fixed to a tripod, and with the lens pointing down toward a table surface (50 cm from the ground) rapid photographs of each frame were taken using a shutter release.

7. The first author worked with a realistic approach in order to reflect the factual nature of the story as described by elders. This stylistic approach is also referenced in social science research. As part of their research exploring local memories in rural Portuguese villages, Ana Isabel Afonso and Manuel João Ramos (2004: 87) describe the ‘aesthetic and representational power’ of realistic drawings in addressing aspects of their inquiry.

Challenging colonial history through storytelling and artistic practice

In this subsection, we offer a brief overview of political developments that shaped contemporary Tłı̨chǫ society. These developments are foundational to many present-day cultural projects – including the storytelling work discussed in this exposition. We begin with an overview of economic and social changes that transformed northern Canada in the twentieth century.

Aggressive industrial expansion in the north had a profound impact on Tłı̨chǫ and other Dene communities during the late 1960s. In an effort to protect the interests of Athabaskan-speaking peoples, northern Indigenous leaders established what became known as the Dene Nation – a political body that, in 1973, claimed an interest in over one million square kilometres of land in the Northwest Territories (Coulthard 2014: 57). This claim challenged colonial interpretations of history – specifically the presumption that Indigenous lands had been surrendered through the signing of treaties (between the Crown and Dene chiefs) in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. According to oral interpretation, Dene elders understood Treaty 8 (signed in 1899) and Treaty 11 (signed in 1921) not as agreements to surrender land but as expressions of peace and friendship (Coulthard 2014: 58).

After extensive oral testimony, the Supreme Court of the Northwest Territories stated, in 1973, that ‘it was unlikely that the Dene had knowingly extinguished their title to the lands covered by Treaties 8 and 11’ (Coulthard 2014: 58). This significant legal acknowledgement of oral history opened a new chapter in the north – prompting events that eventually led to regional land-claim agreements, including the establishment of Tłı̨chǫ self-government, which came into effect in 2005.

For the Tłı̨chǫ, the pathway to self-government was based largely on oral storytelling. During negotiations in 1995, elder Alexis Arrowmaker articulated the importance of remembering the verbal agreement: ‘We want to make sure that the modern treaty reflects our oral version of the original treaty’ (Scott 2012: 213). After 2005, the mission of various Tłı̨chǫ Government agencies, as senior advisor John B. Zoe notes, has been ‘to see if the story can be retold, giving recognition to our language, culture and way of life’ (Zoe, Martin, and Gibson 2012: 148–49).

Oral storytelling continues to be a vital part of contemporary Tłı̨chǫ culture (Scott 2012). Similar to the initiatives of previous generations, storytelling today remains an essential tool through which to assert identity while transmitting ancestral knowledge. The work described in this exposition offers an example of how this traditional know-how may be combined with artistic practice – making for a unique educational experience that is situated outside dominant Euro-Western culture.

This work also aligns with scholarship on the Indigenisation of education (Jacobs 2008; Warner and Gipp 2009; Antoine and others 2018; Archibald 2019). For Linda Tuhiwai Smith (1999: 4), stories from the past can be important educational resources while also providing spaces ‘of resistance and hope’. The community-based visualisation of oral history generated through this research builds on the resistance of previous Dene leaders who used regional stories to challenge colonial narratives of the north. Artistic practice offers a unique educational tool through which to continue challenging colonial interpretations of history. Such a tool is strong like two people – combining ancestral memory with the image-making skills of young people, oral storytelling with moving image production.