The revitalization of Greco-Roman classics and the rise of humanism in the 17th century brought with it a renewed interest in an ancient branch of medicine known as humorism. Humorism conjectured that four bodily fluids—blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm—were the root of all illnesses, and that emotions were triggered by a surplus or deficiency in one or more of these humors.1 Numerous philosophers and scientists recorded their own observations of how the balance of the humors was experienced and exhibited by the human body. According to René Descartes’ Passions of the Souls (first published in 1649), there were only six basic emotions or ‘passions’ that could be produced by the human body: wonder, love, hatred, desire, joy, and sadness. Regarding the passion ‘sadness’, Descartes wrote: “In sadness I observe that the pulse is weak and slow, and we feel as if our heart had tight bonds around it and were frozen by icicles that pass their cold on to the rest of the body. But sometimes we still have a good appetite and feel our stomach doing its duty, provided there’s no hatred mixed with the sadness”.2 Descartes continues to explain the reasons for certain physical representations of sadness, such as weeping being a combined product of the cooling of the blood and constriction of the eye’s pores, and groans as a reaction of the lungs as they are “swollen by the abundance of the blood that enters them and [expel] the air they [contain]”.3

These explanations and subsequent categorizations of the passions were commonly used by creatives, particularly those in the performing arts of drama and music. In their attempt to imitate nature and recreate the sensations felt in the body by certain passions, composers were creating works that not only moved their original audiences emotionally but would also continue to do so for centuries to come.

5.1 A hormonal-harmonic experience

While we may now view the 17th-century explanations of the humors and passions as outdated, present-day scientists are still investigating how and why we feel certain emotions. As the act of listening to music stimulates multiple areas of the brain simultaneously,4 it can often cause an involuntary emotional response as the memory centres of the brain are triggered. Some of us may even find ourselves moved to tears: a response to intense emotion that some theorize is both an attempt for the body to regain hormonal balance and a visual signal to others of a mutually shared experience or the need for assistance.5 This activation of emotion not only allows us to live through the stories being portrayed; it also triggers a secondary hormonal response that occurs after the music has ended. When experiencing feelings of sadness or other intense emotions, the levels of hormones within the body shift out of their normal state. The body then sends a delayed release of endorphins (hormones responsible for feelings of pleasure, such as serotonin and dopamine) in order to re-balance. This is why we often feel better after crying during a moment of grief—the hormone prolactin, which is released when we cry, enhances the secretion of dopamine in what is known as a “negative feedback loop”.6 The same principle can be applied to the emotional and hormonal events that happen within our body when listening to a piece of music – an emotional response fueled by the release of different hormones occurs; the body rebalances its hormonal levels by releasing endorphins; and we are left with a feeling of euphoria that stays with us after the music has ended. This is a possible explanation for why particularly emotionally charged works of music, such as Laments, leave a strong impression on their listeners.

While 17th-century composers of Laments did not know these biological reasons for why humans respond emotionally to music, their compositional components were perfectly tailored to illicit these feelings.

5.2 The bass as a guide for grieving

In 1601, Giulio Caccini published a set of monodic songs and madrigals entitled Le nuove musiche: a collection that is now used to mark the “inception of genuine monody”.7 In the preface to this collection, Giulio Caccini remarks on the declamatory and emotional benefits of the new stile moderno, remarking: “Having thus seen, as I say, that such music and musicians offered no pleasure beyond that which pleasant sounds could give—sorely to the sense of hearing, since they could not move the mind without the words being understood—it occurred to me to introduce a kind of music in which one could almost speak in tones, employing in it (as I have said elsewhere) a certain noble negligence of song, sometimes transgressing by [allowing] several dissonances while still maintaining the bass note […] Thus originated those songs for a single voice (which seemed to me to have more power to delight and move [one] than several voices together) which I composed […].”8

This style of vocal music, featuring a prominent solo line and simple accompaniment, was quickly adopted by other composers of the time and became standard for dramatized musical works. Although not all the Laments in this study are strictly written in the stile moderno, the importance of setting text to convey emotion carries throughout, as does the use of basso continuo.

The flexibility of basso continuo provides a perfect base for text-driven compositions, as it enables a higher level of dramatic freedom for the performers. Certain words can be given an agogic accent by the soloist and supported by a textural change in the accompaniment to better emphasize the chosen interpretation of the narrative. This, as a vocalist, also enables one to live in the music making as there is room for individualized expression within the score and the performance. To better analyze the benefits of specific basslines styles, the Laments in this study have been divided into three sub-categories: recitar cantando, chaconnes, and hybrids and anomalies.

5.3 Recitar cantando

Defining the parameters of what constituted a Lament in the recitar cantando category proved a difficult task, particularly when the Lament in question was an excerpt from a larger work, as defined sections within a scene were rare. Recitar cantando features a vocal style rooted in regular speech patterns, with an unaffectedly paced delivery of text and selective use of textual repetitions. As such, it is perfectly suited to carry an ongoing narrative and offers an ideal medium on which to project quick and decisive dramatic shifts, either from the perspective of a single character or with the interjections of others. The overall simplicity of the accompaniment highlights the text, and all involved in the music making must be aware of the narrative and emotional impulses to make decisions regarding declamation and musical texture. There are, however, clear signals as to when a colour or textural shift may be needed—for example, the rate of harmonic change, the inclusion of rests or fermatas, or a change in meter. The compositions within this study that predominately utilize recitar cantando are the excerpts from L’Orfeo, “Lamento d’Arianna”, the excerpt from Historia di Jepthe, “Ferma, lascia, ch’io parli”, and the excerpt from Cephale et Procris.

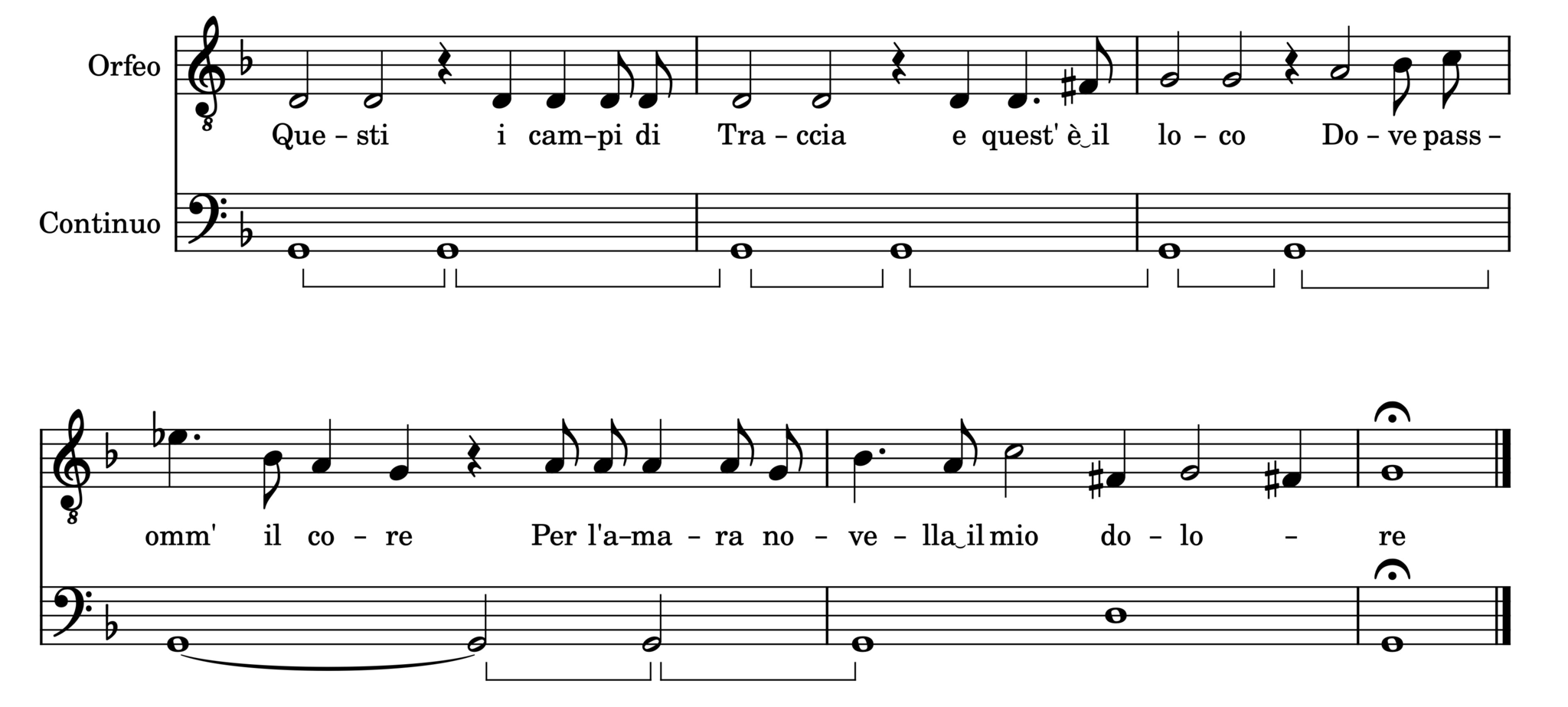

The excerpt from Act V, Scene I of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo begins with an extended drone in the bass. The relative inactivity of the accompaniment gives the singer ample opportunity to colour the language with declamatory efforts and the stressing of the notated dissonances. This simplicity also allows the colours of the voice to be audible, as the singer navigates several vocal registers within the short passage. The sudden harmonic change on the word “dolore” is a clear indication of the overarching subject of grief within the excerpt.

As the Lament progresses, the harmonic rhythm increases with sections that move rapidly to accompany a great influx of text, and pulls back to create a sense of subdued emotion.

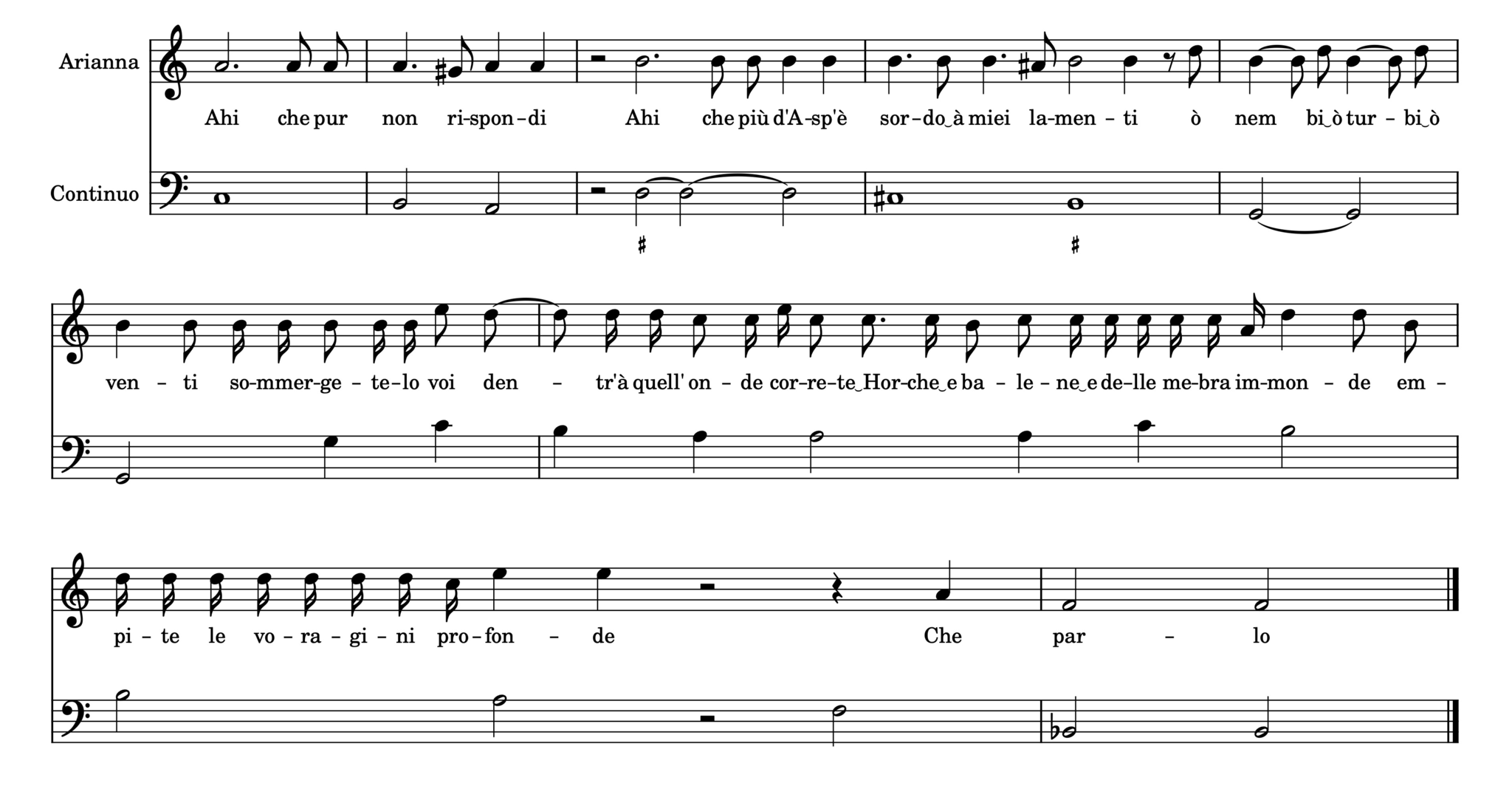

In the “Lamento d’Arianna”, Monteverdi utilizes the same techniques, beginning with a slow rate of change in the bass and later developing the accompaniment to match the increased urgency of Arianna. Example 2 is taken from the emotional climax of the Lament, as Arianna calls on the forces of nature to sink the ship on which Theseus sails away from her.

Here, there is a dramatic change in the activity of the bass coinciding with an increased rate of textual articulation. A moment of silence is introduced to mark the end of the heightened emotional episode before the normal rate of harmonic change is restored as Arianna reflects on her sudden outburst.

5.4 Chaconnes

Although chaconnes may have a clearer harmonic structure than pieces utilizing recitar cantando, they too offer dramatic benefits to the presentation of the text. The stability of the repeated bass pattern acts as a pensive medium that allows one to mentally process the narrative without the distractions of harmonic anticipation, particularly since the entirety of the chaconne pattern is usually played before the entrance of the voice.9 The realization of the bass is still adaptable to the needs of the vocal part, whether harmonically or texturally, but as its foundation repeats with little to no alteration, more precedence is placed on the vocalist to emphasize the emotive qualities of their solo line. The compositions within this study that predominantly utilize a chaconne bass are “Lamento della Ninfa”, “Dido’s Lament”, and “The Plaint”.

In “Lamento della Ninfa”, the simplicity of the repeated four-note chaconne bass complements numerous register changes for the soprano. These changes are strategically aligned with the text to shift the vocal colour in a manner that reflects the emotional intention of the respective passage. For example, the line “Se ciglio ha piu sereno colei ch’el mio nó è” begins in a register that is low for a soprano voice, resulting in a colour that is serene and only possible when the accompaniment can offer support that does not overpower this softer timbre. The vocal line then climbs upwards, repeating ‘colei’ several times before the utterance of “ch’el mio non è” at its peak. An accompaniment that is able to wax and wane with the solo voice is imperative to not only allow the text to be heard, but also to protect the overall vocal health of the singer as they navigate more difficult registers.

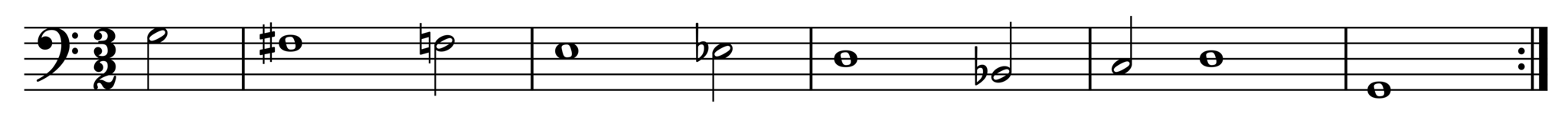

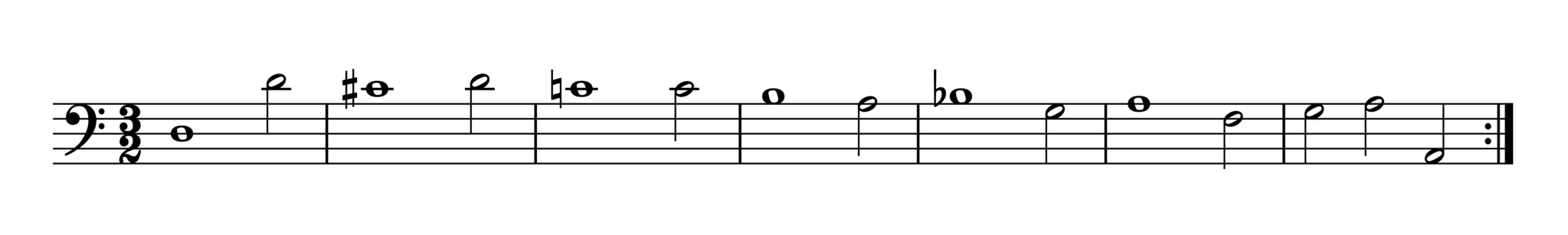

Both of the works by Henry Purcell in this study use a more complex, chromaticized chaconne bass. The extensive chromaticism creates an overarching sense of tension that is still adaptable to the needs of the vocal line. In both works, the amount of sung text is reduced to only a few repeated lines, furthering the need for thoughtful declamation. Declamatory practices and other methods of vocal expression will be further explored in Chapter 7.

Although it is not necessarily the most used bassline, the chaconne is the setting most commonly associated with Laments, and a chaconne bass can also be referred to as a ‘lament bass’. This is perhaps due to its memorability, as the continuous repetition of the bass is easily absorbed and recalled.

5.5 Hybrids and anomalies

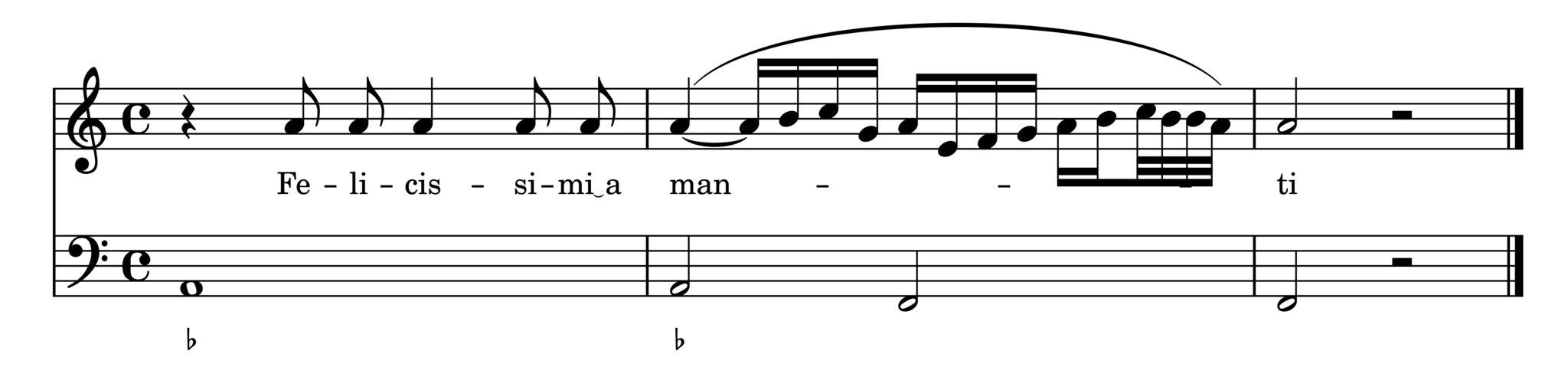

Within this study there were four pieces that did not fit into the categories of recitar cantando and chaconnes. Barbara Strozzi’s “L’Eraclito amoroso” includes substantial sections of both styles, utilizing each for a different dramatic affect. The opening lines, which utilize the recitar cantando style, act as an introduction to the story:10

A simple four-note chaconne bass is then used to accompany a passage that actively describe the act of lamentation, and a short segment of recitar cantando ties off the piece. “Misero Apollo” from Cavalli’s Gli amori di Apollo e Dafne follows the same structure: a recitar cantando recapitulation of what has occurred, a chaconne bass to accompany the lamentation itself, and a return to recitar cantando at the end. The chaconne bassline in the second part of “Misero Apollo” includes a simple four-note unit but regularly deviates from this ground bass, offering increased harmonic variety. The other Strozzi work in this study, “Lagrime mie”, also includes a small portion of chaconne bass with the text “Se dunque è vero ò Dio che sol del pianto mio”, although not for the purpose of distinguishing a moment of heightened emotion. Instead, the short section takes the impetus of the story out of the hands of the narrator and refers to the will of destiny.

Francesca Caccini’s “Lasciatemi qui solo”—although vaguely recitar cantando in its textual setting—has a clear, repetitive stanza structure not seen in the other works. Each of the five parte are of roughly the same length and follow a similar harmonic progression, with slight lengthening in certain phrases to accommodate the written-out variations in the vocal lines.

In Example 5, the basic melody is presented. Example 6 shows a written-out ornamentation of the original melody, supported by the lengthening of the basso continuo accompaniment by two beats. This maintains the harmonic integrity of the stanza pattern while allowing an intensification of the vocal line and a shift in the energy of the character. Each of the first four parts is also concluded with the exact same harmonic and melodic setting of “Lasciatemi morire”. The end of the fifth and final part, although it uses a different text, also uses a similar setting that cements the uniformity of the stanza pattern.

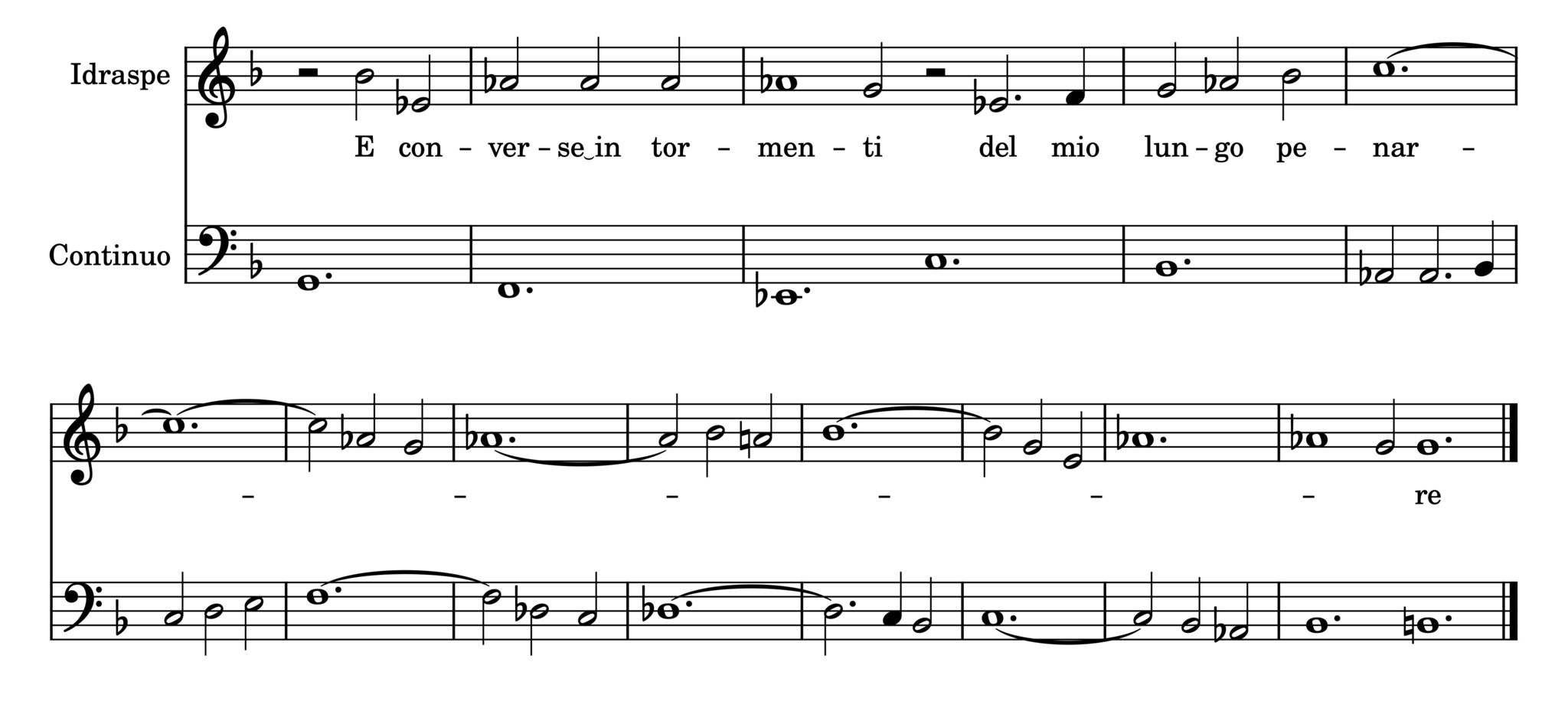

“Uscitemi dal cor lagrime amare” from Cavalli’s opera L’Erismena proves an anomaly with its legato vocal lines and use of ritornello sections. Although the interweaving ritornellos are reminiscent of 16th-century choral works, the use of basso continuo grounds this Lament in 17th-century compositional practice. This aria also utilizes a call and response motif between the voice and continuo not seen in the other works studied, providing numerous opportunities for timbral changes and emotional nuance on the singular word ‘penare’.

5.6 Writing new basslines

While the bass was the starting point in setting my chosen texts, I found it to be the least creatively inspiring part of my compositional process. Due to the importance of exploring diverse avenues within the project, I choose four different bassline styles for the compositions. The basslines themselves were assigned after a discussion with the librettists about what they enjoyed from their Spotify listening assignment, as well as considerations regarding what voices I wished to use for the initial recording. “Carry Me” is written in the recitar cantando style, “Sharks” draws heavy influence from Cavalli’s “Uscitemi dal cor”, “Autumn Oud” follows a stanza-derived pattern similar to that of “Lasciatemi qui solo”, and “something pulls me up” was assigned a simple four-note chaconne bassline to best fit with the musical style of Actual Human People—the musical duo collaborating with librettist Tanisha Nuttall on the song.

1. Faith Lagay, “The Legacy of Humoral Medicine,” AMA Journal of Ethics (July 2002), accessed August 25, 2022, https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/legacy-humoral-medicine/2002-07.

2. René Descartes, Passions of the Souls, trans. Jonathan Bennet (2017): 28, 2017, accessed August 26, 2022, https://www.earlymoderntexts.com/assets/pdfs/descartes1649part2.pdf.

3. Ibid, 36.

4. TED-Ed, “How playing an instrument benefits your brain – Anita Collins,” YouTube video, 4:44, July 22, 2014, accessed August 25, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R0JKCYZ8hng.

5. TED-Ed, “Why do we cry? The three types of tears – Alex Gendler,” YouTube video, 3:58, February 26, 2014, accessed August 25, 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=keMF8YzQoRM.

Michael S. A. Graziano, “The origin of smiling, laughing, and crying: The defensive mimic theory,” Cambridge University Press, March 3, 2022, accessed November 21, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1017/ehs.2022.5.

6. “Prolactin,” You and your Hormones, accessed August 19, 2022, https://www.yourhormones.info/hormones/prolactin/.

7. Nigel Fortune and Tim Carter, “Monody,” Grove Music Online, 2001, accessed August 28, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.18977.

8. Giulio Caccini, Le nuove musiche, trans. H. Wiley Hitchcock (Madison: A-R Editions, 1970), 44-45.

9. One should note that, while this is often the case for vocal works, the entirety of a chaconne pattern may not be played as an introduction before the entrance of the melody in instrumental works.

10. See Appendix A for the full texts and translations—all textual quotes from Laments are copied as they appear in the score.