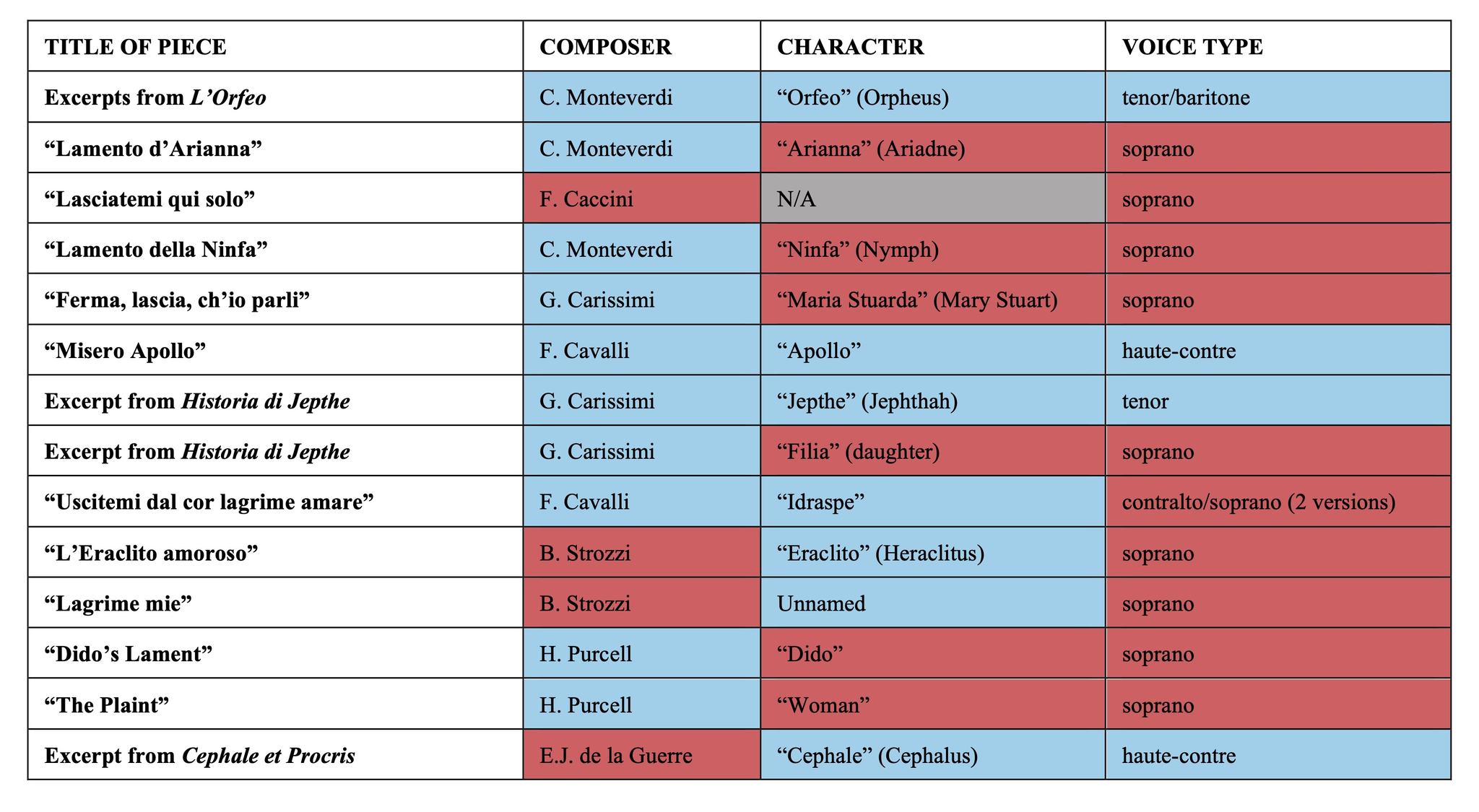

While the number of Laments written in the 17th century is substantial, the repertoire is not evenly distributed among the standard voice types of the time. The majority of Laments were written for the soprano voice,1 and even when the characters were listed as male, it was not uncommon to cast the Lament for a female singer. The search for Laments written from the perspective of male characters proved difficult, resulting in the expansion of the parameters regarding what constituted a Lament to include excerpts from large works. Table 2 lists the pieces included in this survey of 17th-century Laments, identifying the genders of their respective composers, character, and voice types.2 Blue denotes the male gender, and red the female.

Although the gender of the character usually matched the gender of the voice type for which it was originally set, there are several exceptions within this study: Eraclito (the male philosopher Heraclitus) is sung by a female soprano; Idraspe (a male prince) is sung by a female contralto; and the unnamed speaker of Strozzi’s “Lagrime mie” is sung by a female soprano. In the case of “Lagrime mie” the speaker can be inferred to be male, as object of their love is given the feminine name ‘Lidia’, and it is unlikely that a homosexual relationship would have been used as the narrative base for this musical composition.

The gender of the composer has been included to demonstrate the correlation between composers and the characters for which they choose to write Laments. The majority of works written by male composers included in this study were composed for a female character, while all the works composed by a woman in which the character’s gender was identified were designated as men. The reason behind this correlation is currently unknown.

6.1 The emotional voice: society and biology

With the societal expectation for men to restrain their expressions of grief, as well as the relegation of active lamentation to women both in literature and in professions such as keeners and other hired mourners, it is unsurprising that most Laments were intended to be performed by women whether or not the characters themselves were female. The conventions of Greco-Roman classics had previously established an association of laments with a feminine voice, and Plato described “tragic laments as womanly”.3 Although this uneven casting of voices can largely be explained by the gender conventions of the time, there are also several biological factors as to why a female voice may have been favoured for use in this aural craft, as well as why certain compositional elements are more frequently connected with a specific voice type.

When we are experiencing an intense negative emotion, our body attempts to increase the amount of oxygen taken into our lungs by keeping the glottis open.4 In order to achieve this, the muscles of the throat constrict, creating the feeling of a lump in your throat, known as the “globus sensation”.5 This constriction can also contribute to a rise in pitch when speaking under emotional strain. As the female voice is naturally higher than the post-pubescent male voice, it is able to more readily replicate this rise in pitch. Women are also more likely to be seen crying than men—according to a study conducted in the 1980’s by biochemist William H. Frey, “women cry an average of 5.3 times a month, while men cry an average of 1.3 times per month, with crying defined as anything from moist eyes to full on sobbing.”6 The hormone associated with the release of tears, prolactin, is seen in higher levels in women than in men, and the hormone testosterone (which is seen in higher levels in men than women) may inhibit crying.7 Physical emotional displays are therefore more often associated with women, and, as such, Laments for women often include motivic elements that imitate these actions.

Between these biological factors and the societal norms of the 17th century, it is easily conceivable why the majority of Laments are slated for the highest of the female voice types: the soprano.

6.11 The soprano

The Lament repertoire available for sopranos is widespread and varied, often serving as the emotional climax in large scale works, or else existing in stand-alone song settings. As all of the Laments for sopranos surveyed in this study are triggered by an event outside of the speaker’s control, the text is set to emphasize the internal feelings of grief felt as opposed to expressions of regret or remorse. The grief itself is coloured by a combination of various styles, motifs, and tempos included in the score, or else by declamatory choices made on the part of the soloist. The result is a collection of Laments that range anywhere from angry disbelief to melancholic reflections on an unfortunate situation. “Ferma, lascia, ch’io parli” and “Lasciatemi qui solo” fall at either end of the spectrum, with the former presenting a fiery and enraged noblewoman, and the latter a more gentile acceptance of a woman’s all-consuming feelings. “Ferma, lascia, ch’io parli” utilizes the entire height of the soprano range in displays of virtuosic ferocity, with energetic melismas that appear out of the recitar cantando texture. “Lasciatemi qui solo” stays in the mid-to-low range of the voice, resulting in a softer vocal quality that can bring both an elegance and natural fragility to the singing. The final line of each stanza sits at the lowest point of the utilized range, exhibiting the inescapability of the grief even amidst the presence of beauty.

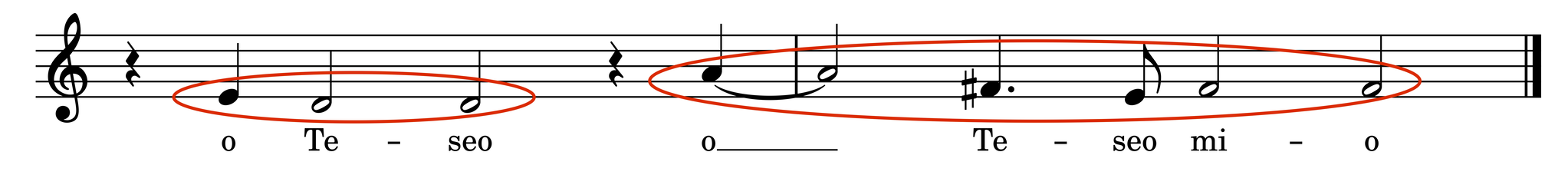

Motivic tears, wails, cries, and the like are clearly featured in the “Lamento d’Arianna”, “L’Eraclito amoroso”, “Lagrime mie”, and the Laments of Filia. “Lamento d’Arianna” has two distinct versions of wails and sighs: the first a pained expression of overwhelming grief, and the second a remembrance of her love for Teseo. The grief-fueled wails are created with a dissonant ascending chromatic line stretched over a single syllable and appear several times within the Lament.

The moment of remembrance is easily identifiable within the text (“o Teseo”), and the respective sighs are created by two notes moving a downward movement. This gesture is also borrowed for an utterance of “morire”, resulting in a heartbreaking association between Arianna’s love for Teseo and her misery at having been abandoned by him.

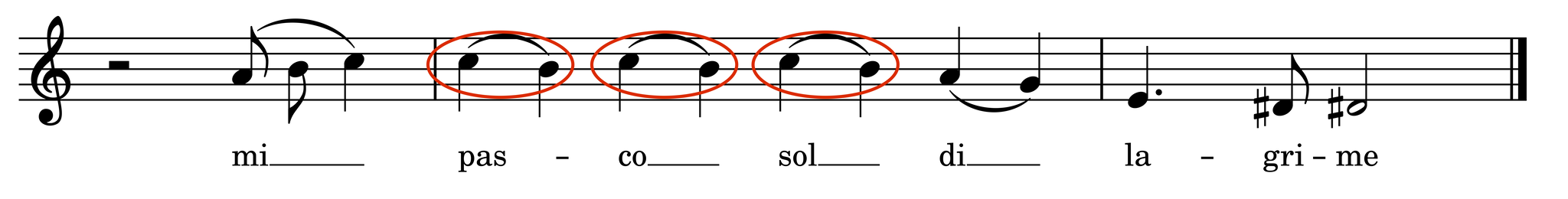

“L’Eraclito amoroso” presents the tears simply yet effectively with the use of a repeated descending semitone. In “Lagrime mie”, the opening line acts as a series of sobs that leads to—but does not complete—the first cadence, painting only the words “my tears” before the phrase is concluded with the line “why do you hold back?”. This sequence is emblematic of the entire Lament, which centres around the absence of tears in the presence of grief.

The cries of Filia are uttered as short sets of ascending sixteenth notes which are echoed (by two additional sopranos) in the caves as she wanders the mountains. These short gestures offer a direct physical correlation with the act of sobbing, as their executions require the same type of abdominal engagement that would naturally occur in an autonomous sob.

“The Plaint”, “Dido’s Lament”, and “Lamento della Ninfa” each utilize numerous textual repetitions set to their chaconne bass. The relative simplicity of the melody requires the singer to make decisions as to how to colour the repeated texts. In the foreword to “Lamento della Ninfa”, Monteverdi gives his permission for the singer to take liberties with the notated rhythms, and suggest that the solo should instead be sung “at the time of the soul, and not at that of the hand”8 (‘hand’ in this instance meaning ‘tactus’). As such, each performance of the Lament is intended to be felt as it is sung, requiring the singer to recreate emotional impulses in the moment.

6.12 The contralto

Only one work within the study, “Uscitemi dal cor lagrime amare” from Cavalli’s opera L’Erismena, was intended for the low female voice. Although Idraspe is the leading male character of the opera, he is not the main protagonist; the hero of the opera is its title character Erismena, a woman disguised as an Armenian soldier. The weaker characterization of Idraspe against the strong Erismena (slated as a soprano) could be a contributing factor in the casting of a female voice for the prince. Unlike the pieces written for sopranos, which generally emphasize natural speech patterns in their deliveries, “Uscitemi dal cor lagrime amare” is built on incredibly long melodic lines and an interplay between the bass, ritornello, and singer. The central range of voice enables the ritornello and continuo to surround the melody, creating a feeling of restraint and containment of the solo line. While the regularity of the form and harmonic pacing may inhibit the stark emotional shifts seen in recitar cantando Laments, it allows for a more constant play of dissonance and resolution as melodic lines are exchanged between the contralto and the instrumentalists. The aria therefore achieves its emotional core through the creation of harmonic tension and restraint; a practice that is not only appropriate for the societal expectations placed on the men of the time, but also foreshadows the melodic style of the operatic Laments in the 18th century and onwards.

Two versions of the aria “Uscitemi dal cor lagrime amare” are now used: the original low-voice version, and a higher transposition suitable for a soprano. It is common in modern productions for the role of Idraspe to be sung by a countertenor, likely due in part to the rarity of the true contralto voice.

6.13 The haute-contre, the tenor, and the baritone

The roles of Apollo and Cephale are both intended for haute-contre; Jephte is billed as a tenor; and Orfeo is suitable for a tenor or high baritone. The absence of the bass voice within the Lament repertory may be due in part to the biological associations of higher voices with expressions of grief, but is more likely a result of the operatic trope-casting in which basses were often set as unwavering political forces, such as kings and gods.9

“Misero Apollo” from Gli amori di Apollo e Dafne bears many similarities to the other Cavalli work on this list, “Uscitemi dal cor lagrime amare”. Just as with Idraspe, Apollo is the male lead, but not the main protagonist; Apollo is directly responsible for the source of his grief, as he himself chased the nymph Dafne until her only possible source of escape was to be turned into a laurel. The melodic portion of Apollo’s Lament and “Uscitemi dal cor lagrime amare” both include the long, fluid vocal lines characteristic of Cavalli’s operas. Where the two works deviate from one another is in the latter half of “Misero Apollo”, when Apollo calls on Jove to relieve him of his duties as the sun god and to allow him to sink into the ocean—a form of masculine action to combat grief, as was earlier explored in Shakespeare’s Hamlet!. A stark change to accompany this call to action is achieved through the switch from a chaconne bass to an impassioned recitar cantando.

The remaining four Laments written for the male voice exclusively use a recitar cantando style that lacks the defined forms seen in many of the recitar cantando settings for sopranos. The presentation of the respective texts generally follows a more regular speech pattern, with less shifts in overall emotional colour. The passages of Jepthe and Cephale are both incredibly short and leave their female counterparts, Filia and Procris,10 to amplify the emotional aspects of the given scene.

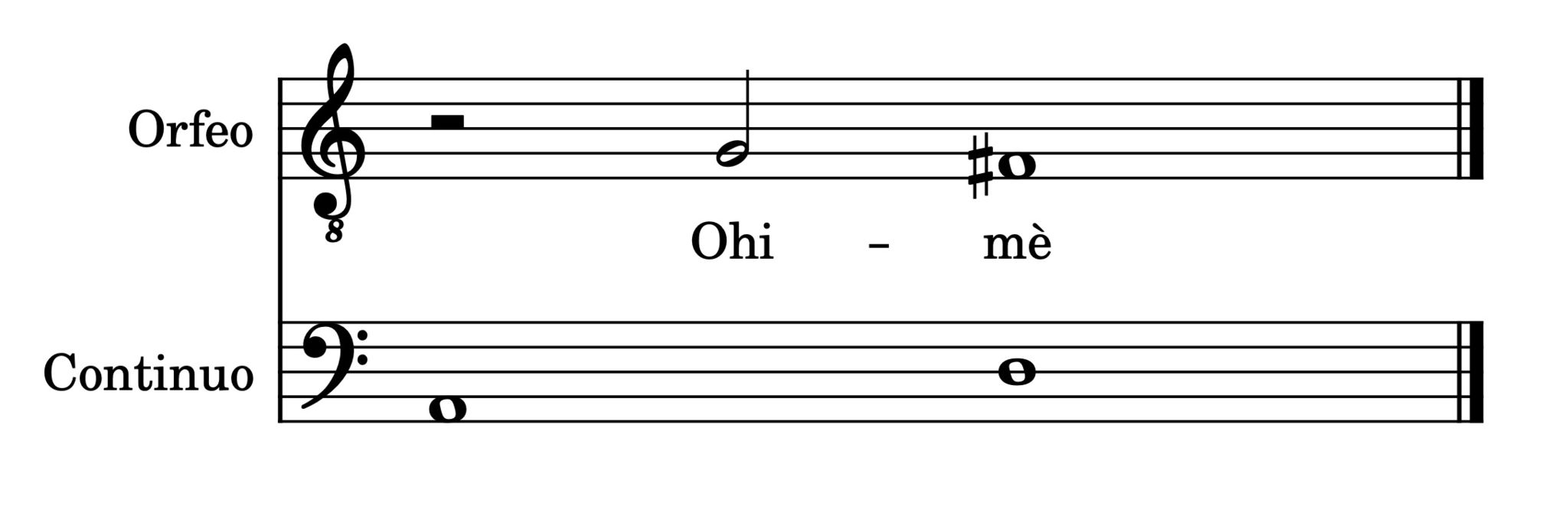

The excerpts from L’Orfeo, the oldest of the works used in this study, hold great influence over subsequent Laments, particularly the “Lamento d’Arianna”. Orfeo’s single ‘ohimè’ upon learning Euridice has died is most certainly a forebearer to Arianna’s many sighs.

Intense emotional colour is achieved through numerous dissonances, and variations in the pacing of the text suggest psychological shifts (although the contrasts are not nearly as dramatic as those seen in the “Lamento d’Arianna”). Orfeo too presents a masculine call to action, as he announces that he will retrieve Euridice from the underworld. This call, unlike Apollo’s, is a necessary convention to further the narrative as opposed to just a representation of grief. Specific rhetorical techniques used in the Laments of Orfeo, as well as their subsequent relation to the “Lamento d’Arianna”, will be further explored in Chapter 7.

6.14 The question of the castrato

The absence of the castrato within this genre is due in part to the casting traditions of Baroque opera. Towards the latter part of the 17th century, castratos were primarily slated as the leading male protagonist in operas and their characters were often members of the nobility. The heroic nature of their roles required with it the emotional stability dictated by society for upper-class males, negating the option for an immensely emotional piece like the Lament.

There is the possibility that, at times, the soprano roles in operas could have been sung by a soprano castrato en trevesti,11 as the two were occasionally interchanged in the Italian operatic works. It is, however, unlikely that they were used in the operas of Henry Purcell, who favoured the countertenor voice and made a clear distinction between the two when setting vocal music. The castrato voice was also unlikely to be the preferred choice for any of the Laments set as independent songs, as their large and present sound was better suited to the operatic and oratory repertoire.

6.2 Casting Arianna: ‘La Romanina’ and ‘La Florinda’

With the patron-musician system of the 17th century came close partnerships between composers and the persons that would perform their works. Composers often knew who would be premiering their works while they were still being written, thanks to the established network of court musicians. In some cases, an entire work or role was centered around a specific musician, and many composers of vocal music would favour a specific singer when casting their operas.

The title role of Monteverdi’s L’Arianna was originally created for Caterina Martinelli, a young virtuosic singer who was mentored in Monteverdi’s own household. Martinelli, or ‘La Romanina’ as she was often called, was an important status symbol of the Manutan court, as she had been discovered by the Gonzagas12 and brought to Mantua to be educated by the Monteverdis and to perform at court.13 Tragedy struck when, on March 7th, 1608—less than three months before L’Arianna was to be premiered—La Romanina died of smallpox, leaving the opera without its leading lady.14 A replacement was found in Virginia Ramponi-Andreini (known as ‘La Florinda’), a celebrated actress who possessed a good-singing voice. La Florinda’s performance was a great success, and she later sang the title role in Monteverdi’s Il rapimento di Proserpina.15 With her background in theatre, and accounts praising her moving performance, La Florinda’s ‘Arianna’ was likely grounded in thoughtful emotive and declamatory practices, as opposed to a demonstration of virtuosic singing. As the “Lamento d’Arianna” served as major source of inspiration for subsequent laments, this grounding in declamation is a key component in unlocking the emotive core of Laments and will be further examined in Chapter 7.

6.3 Casting Laments for a Modern World

As a major motivation of Laments for a Modern World was to create works that are relatable and accessible to a wider audience, it was important to represent the versatility of the compositions within the premiere presentation. Special care was given to diverse casting, not only in terms of the nationalities and ethnicities of the performers, but also their musical styles and individual timbres.

For “something pulls me up”, Tanisha Nuttall was interested in melding Laments with a folksier style, resulting in the collaboration with Actual Human People. Anna Eastland, having heard my own recordings online, requested that I sing “Carry Me” for its debut performance. For “Autumn Oud,” singer Kaan Yazıcı was invited to add his traditional Turkish folk inflections to the inaugural recording. Since the inception of “Sharks” has a strong tie to Hong Kong, I asked Edmond Chu—a tenor from Hong Kong who is currently based in the Netherlands—to be one of the two voices premiering the work. Canadian soprano Shanice Skinner was chosen as the second voice as her vocal quality was a good match for Chu’s, and I knew her singing to be incredibly expressive and emotionally moving. Both Chu and Skinner are classically-trained operatic singers with voices that can carry well over an ensemble—a necessity as the piece was given a slightly more robust instrumentation for its debut. While these Laments were composed with certain singers in mind, I refrained from composing anything overly virtuosic within the score in order to keep the works accessible and adaptable.

1. As many of these Laments sit very low for the modern classification of a soprano range, they are commonly sung by mezzo sopranos; a term that did not exist in the 17th century.

2. Referring to the traditional gender-voice type parings of the time.

3. Blair Hoxby, “The Doleful Airs of Euripides: The Origins of Opera and the Spirit of Tragedy Reconsidered,” Cambridge Opera Journal 17, no. 3 (2005): 260, accessed June 18, 2022, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3878297.

4. Josh Hrala, “Why Do We Get a Lump in Our Throat When We’re Sad?,” Science Alert, June 6, 2016, accessed September 3, 2022, https://www.sciencealert.com/why-do-we-get-a-lump-in-our-throats-when-we-re-sad.

5. Ibid.

6. Lorna Collier, “Why we cry,” American Psychological Association, February 2014, accessed September 10, 2022, https://www.apa.org/monitor/2014/02/cry.

7. Ibid.

8.Translated by Ai Horton.

Claudio Monteverdi, Madrigali guerrieri, et amorosi, libro ottavo [Basso Continuo] (Venice: Alessandro Vincenti, 1638), 55, https://vmirror.imslp.org/files/imglnks/usimg/c/c2/IMSLP37046-PMLP82381-Monteverdi_Madrigals_Book_8.pdf.

9. There are, however, 17th-century sacred Laments written for the bass voice, but they were not included in this study due to their potentially liturgical nature. One such example is Johann Christoph Bach’s cantata Wie bist du denn, o Gott, which is often labelled as a Lament.

10. While Procris’ final text before dying is not defined as a Lament under the parameters set in Chapter 1.5, her substantial recitar cantando passage carries the emotional impetus of the scene, as it occurs onstage directly before Cephale’s short Lament passage.

11. A role in which the gender of the character is opposite to that of the respective actor.

12. The ruling family of Mantua (‘The House of Gonzaga’).

13. Edmond Strainchamps, “The Life and Death of Caterina Martinelli: New Light on Monteverdi’s ‘Arianna,” Early Music History 5 (1985): 156, accessed Septermber 13, 2022, http://www.jstor.org/stable/853922.

14. John Whenham, “Arianna,” Grove Music Online, 2002, accessed September 13, 2022, https://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/grovemusic/view/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.001.0001/omo-9781561592630-e-5000900175.

15. Tim Carter and Anne MacNeil, “Andreini [née Ramponi], Virginia,” Grove Music Online, 2001, accessed September 14, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.41032.

NEXT SECTION:

Chapter 7: Painting the picture

JUMP TO: