It is common to point out the enigmatic nature of the origin of flamenco. In fact, although there are various speculations and theories, the truth is that we lack old written references in which flamenco is mentioned as such until the 18th century1. Despite, we can affirm that the first indications were gestated previously, as a result of the combination of different cultures that coexisted in Andalusia, specifically in the area between Seville, Jerez and Cádiz and that the arrival of the gypsies (emigrants from India who were mistaken with Egyptians) was decisive for its creation, since there was an assimilation and integration of all these cultures, that was expressed as an echo of their sufferings in reduced family environments. ''As a consequence, the first cries were born, a prelude to what later became the cante2 and its subsequent professionalization3''.

Examples that shows the similarities between African rhythm and flamenco clapping (in this case tango clapping).

Indeed, these café cantantes were very important for the professionalization of flamenco, since the gypsies went from singing for free and disinterestedly in a family environment to having a fixed schedule and being paid for it and above all, to being listened to by an audience, which forced them to form a varied and structured repertoire. In the words of López Ruíz: “The cantaor/a learns to build a recital, the bailaor/a gets used to measuring herself with others and the guitarist also learns to give consistency to his style thanks to the harmonical obligation to accompany the cante and the rhythmical one to accompany the dance ”4.

On the other hand, there was flamenco in the theatres, combining gypsies with other people from the classical scene which was also helpful in a way to the professionalization of flamenco, despite the mixing and the loss of the more pure tradition.

We must be aware that we are talking about music that has always been developed orally, transferring from one to another, from generation to generation and in private settings, without initially presenting a specific form or structure and, therefore, there are no scores that help us understand the evolution it has had over the years.

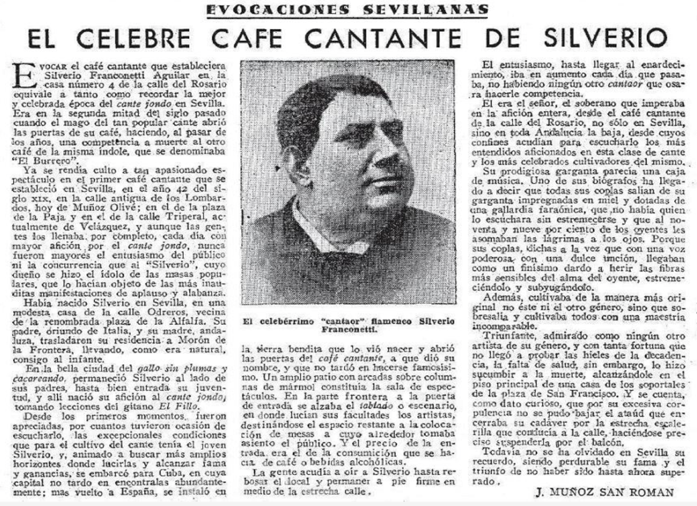

Undoubtedly, there is a long process from these ‘complaints’ to the first recording made in 1898 by Canario Chico and Niño de Cabra5. In this process, some places called the Cafe cantante (singing cafes) (1860-1920) played a very relevant role. Although it is not the object of research, it seems essential to underline the importance they had in the conformation and professionalization of what we currently call flamenco. In this sense, Julián Pemartín synthesizes the atmosphere of these places in the following way: “The singing cafes were installed around a general pattern: a room, as spacious as possible, and decorated with mirrors and bull posters, in which from the chairs and tables intended for the public, the tablao, where the flamenco group performed, was raised'' to which Faustino Nuñez adds:'' but the cafes were not only for flamenco, there could be dances of all kinds, magic and even calf fighting6''

Therefore, we could say that this music was germinating naturally in the homes of people belonging to the lower classes of Andalusia, as a need to express the difficulties in which they lived. As a consequence, we can appreciate characteristic songs of the Jewish synagogues, Gregorian songs, Arabic and African rhythms, and others; a manifestation of personal contact between the miscellany of cultures that coexisted.

Let's see some examples:

These are two examples that show the similarities between how melismas are used in moriscos culture (using it to call for the praying) and cante jondo.

The soleares are currently one of the main palos flamencos, perhaps because, as Faustino Núñez points out, “in its musical structure it keeps a good part of the guiding elements (melodies, rhythms, harmonies) of the musical aesthetics of the flamenco genre […] in such a way that no other air has had the capacity to add specific values and qualities of jondo art like soleares 7''.

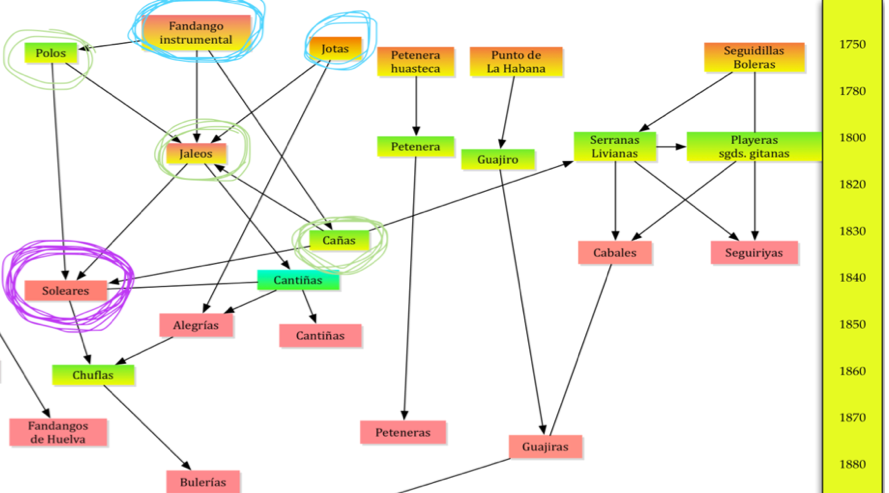

Despite being one of the most played and known flamenco styles and having specific values and qualities of jondo art, we can affirm that it is not the oldest style, since the soleares arose from the contribution of different cantes, including the one with which the greatest similarities have been found: the jaleos. In this graph prepared by Faustino Núñez, we find those that seem to have been of great influence for the creation of the genre that today we call soleares.

As of 1860, it is common to find soleares in the repertoire of flamenco singers. However, it should be noted that the term cante por soleares appears in a documented way in 1851 although it refers to the soleares which took place in the bolero theater environment8. The more academic soleares, therefore coexisted in the theatre and in the more flamenco typical of taverns and street settings. As it is logical to think, there is more documentation of the ones played in theaters, due to the advertisements in newspapers and therefore, there is still no certainty as to whether the solea flamenca came before the academic one or the opposite.

Of all the existing jaleos, there is one that suggests it could be one of the oldest soleares. We refer to the Gariana jaleo that a very young Paquirri el Guanté sang in Cádiz 1847, accompanying himself on guitar. On the other hand, the flamenco tradition points to La Andonda (Seville) as the oldest soleares 9. Flamenco memory has bequeathed us four cantes por soleares by Paquirri and three by La Andonda.

Indeed, there is a certain consensus among flamencologists referring to the idea that the soleares owe a large part of its essence to its direct antecedent, the jaleos. In its beginnings (early 19th century) these cantes encompassed a large number of styles and musical variants, subject to dance, with a lively musical air, a ternary measure, three verses, a joyful theme, and played both in Phrygian, Major, and Minor modes.

Apparently, these jaleos lead to other styles that are better known to us today, such as the soleares or bulerías that were, in that time, gaining importance in the repertoire of the cantaores/as. As is logical, the change in nomenclature was due to the introduction of differential elements between one and another. Specifically, the transition from jaleo to soleá seems to have its origin in the theme or feeling of sadness10. When the jaleos had melancholic lyrics and were played in the Phrygian mode, while the tempo slowed down, giving the cantaor/a much more importance and ceasing to be dependent on dance, they were called solea. There was even a time when those that we know today as soleares were called ‘coplas de jaleos’, due to their happy theme, so there was a moment in history in which both cantes coexisted.