As the flamencologist Faustino Núñez affirms, it is not easy to distinguish the soleares, since their aroma permeates almost all flamenco music, and the variants are very numerous. Without going too deeply into the intricate variety of styles that exist when we refer to soleares and the characteristics or qualities that one and the other possess since this would be a subject for a doctorate, I would like to briefly summarize what some authors state about the different soleares. Firstly, there is a core of soleares between Cádiz- Jerez- Alcalá and Triana. It is commonly said that those of Cádiz are more spoken and direct and that they have a low level of melodic development, being sometimes more told than sung. Those of Jerez are not very well known, while those of Alcalá are the most sung and well-known today. Those of Triana are attributed with the greatest melodic development, as well as with the creation of the 'soleá apolá1'. These characteristics, affirmed by various flamencologists and singers, did not arise because there was a school, but because of the first solea singers and the characteristics of their cantes.

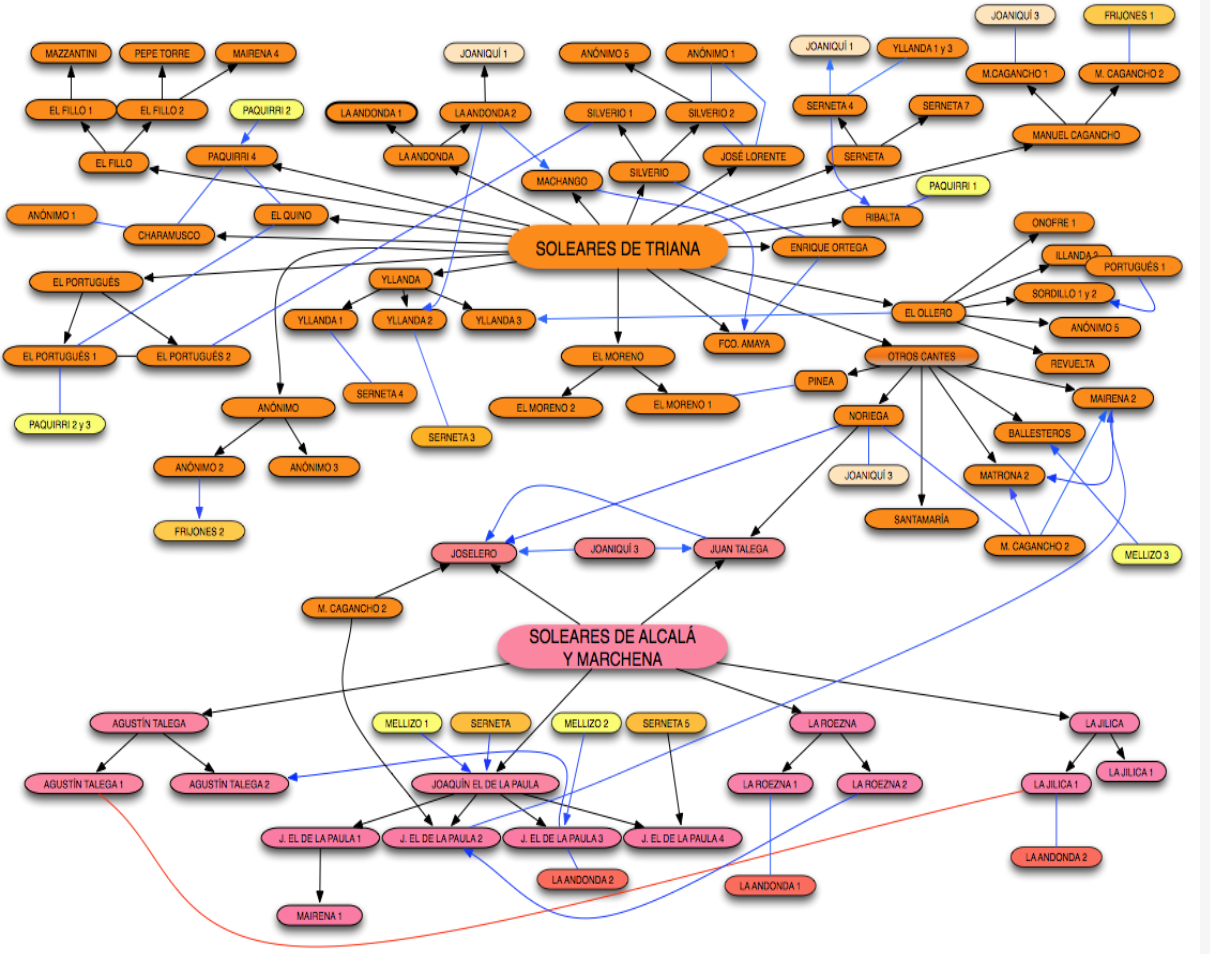

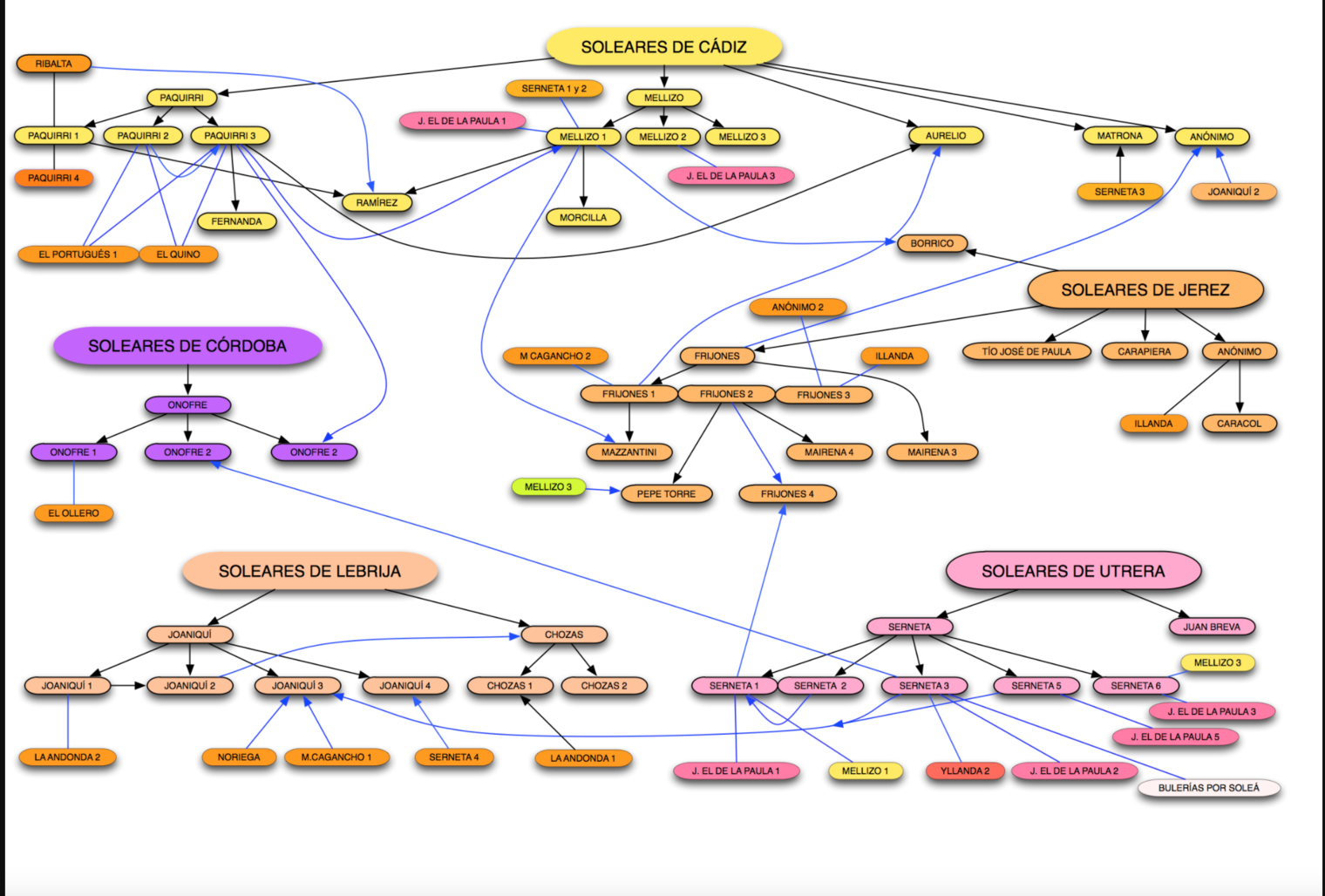

Some experts contend that by living in the same place, the singers influenced each other, and similarities can thus be appreciated in their songs. But it is also possible that we do not find these similarities so clearly, as José Blas Vega asserts; in his book, he elects to classify soleares according to purely musical aspects and concludes that soleares should be classified according to the melodic range that they display. Going back to the classification by geographical area and taking as a reference the book 'Antonio Mairena en el mundo de la Siguiriya y la Soleá', we must take into account that in addition to the classification by geographical area, there is a sub-classification by singers and typology of the soleares that they show. Take as an example the soleares of Paquirri de Cádiz. Initially, they would be classified by geographical area in Cádiz, but then again classified into three blocks: Paquirri 1 (songs to begin with), Paquirri 2 (transition songs), and Paquirri 3 (transition or closing songs). Therefore, the classification of soleares becomes extensive. This classification is summarized in the following graphs by Faustino Núñez, which are based on the conclusions that Luis Soler Guevara and Ramón Soler Díaz point out in 'Antonio Mairena en el mundo de la Siguiriya y la Soleá'.

As in classical music, there are different types of vibrato which classifications may attend to the variations in frequencies and amplitude. Here we are going to study a specific type of vibrato that is commonly used in soleares singing: the Vibrato marcado (marked vibrato). This kind of vibrato is defined by its low frequencies and big amplitude. Consisting in the repetition and emphasis of one note, creating a climax that normally resolves in a descendent way.

This way of doing it is very useful if bebeo is used in a small range and slow tempo, but if the singer uses it in a bigger range and faster tempo, as in the audio of Fernanda de Utrera I find it better to imitate it using a fast portato glissando in the left hand.

Two different suggestions. The first one is imitating Alba Guerrero's vibrato which is more clear and marked. The second one is immitating Manolito de María, who does a faster and more 'dirty' vibrato.

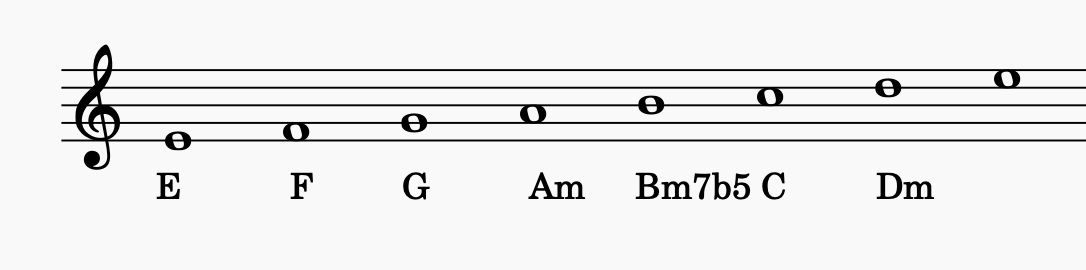

Although in the flamenco language the minor and major modes are used, the soleares are based on the so-called Flamenco Phrygian mode or Andalusian modal tonality. (nota Faustino) This mode collapses characteristics of the Major and Phrygian modes since it uses the chords of the Phrygian mode but with a major chord on the first degree. Thus in E Phrygian, we would use the chords from C Major, except with a major chord on E.

Alba Guerrero defines an attack as the beginning of a note, no matter if this note is at the beginning or in the middle of a musical sentence.

The blown attack:

In the Andalucian phonetic is commonly found the pronunciation of a sounded blown that is produced through expiration. In flamenco singing is commonly used and is also known as 'arrastre' (drag).

Ornaments will not be translated to cello in this chapter but they will be through the playing because I don't need to learn new skills in order to do them. They are exactly the same than in classical music playing so I didn't find it really interesting to show how to translate them to the cello playing.

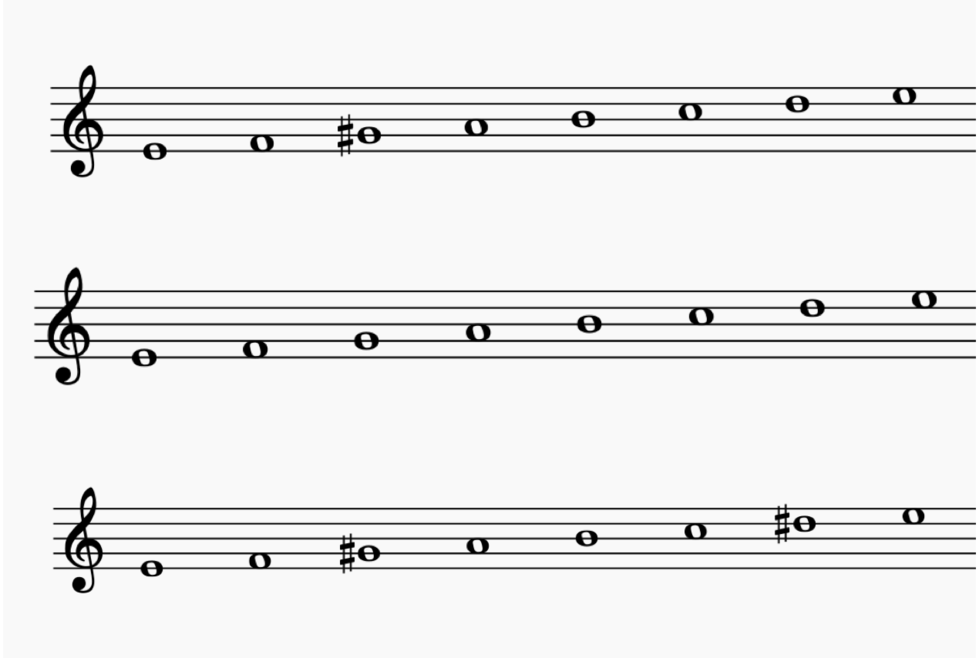

To these chords are usually added the 9th or 11th, the most common and characteristic being the minor ninth that is usually included in the tonic chord. The G# in the tonic is something like a 'blue note', as it may or may not be used in the melody, but the chord will always be major. From this harmonic base, different scales can be used (both in falsetas and in the cante), the most common are the following2.

In the original accompaniments, there were two ways of developing the cadence: what is traditionally called por arriba (or flamenco mode in E) and por medio (or flamenco mode in A). The later incorporation of the capo (cejilla in Spanish) gave decisive support to these positions or postures and retained them in order to greatly expand the number of modes with different names and heights that can be developed, without losing any of the unique sound characteristics. The names of the flamenco tones are due to the movement of the capo along the neck. It is important for any musician who wants to start in the flamenco language to know this, since in flamenco the movement of the capo is used to communicate the decision of the tone. Below is a table with all the tones, taken from the book ‘Flamenco Method for melodic instruments’ by Juan Parrilla3.

Due to this, guitarists are able to adapt to the singer's tone without having to think about different chord positions. So, in flamenco it is very common to transpose depending on which singer is singing, what style he is singing, or how his voice is that day; therefore, we must develop agility in transportation and knowledge of different scales, just like jazz musicians. The book mentioned above ('Flamenco Method for melodic instruments' by Juan Parrilla), offers a series of exercises in different keys for melodic instruments and also the various scales.

Finally, because the guitar has adapted to the cante, it is easier to understand this last one if we also investigate what the chords are and where are they placed while the singer sings. Below is a video that helps greatly in understanding the movement of the chords on the guitar during the soleares, as well as theirstructure.

It is one of the effects used to 'break the voice' in flamenco singing (although it is not the only one). For the singer's technique is a combination between the superior mordent- but more accentuated and therefore with more energy- and the blown attack.

We can differentiate several types of 'jipio', although the one that Alba Guerrero studies in her thesis and the one I am also experimenting with is the one that sounds like what we usually call a 'roster'.

The effects in flamenco singing are characterized by being noises that are emitted with the speech apparatus and that are used to add expressiveness to the sentence.

Bebeo

It is the technique of putting the letter /b/ within a syllable or in front of each one of the notes of a scale to cause an effect similar to vibrato, being an effect that is produced in a labial way for flamenco singers

Before going into the analysis of the different cantes and their own structure, it is convenient to be aware of the articulation of this cante, which, like others in flamenco, is as follows:

- Guitar Intro

- Ayeo de salida

- Cante de preparación (preparation singing)

- Cante de transición (transition singing)

- Cante valiente (brave singing)

* cantaores add as many ‘cantes’ as they want, depending on how long they want the solea to be, and interspersing lyrics guitarists do their falsetas.

It is also worth knowing that there are various types of soleares classified in the flamenco world as follows:

- ‘Solea Grande’ four octosyllable verses with consonant/assonance rhythm.

- ‘Solea Corta’ three octosyllable verses with consonant/assonance rhythm.

- ‘Solea Apolá’ clear references to another cante called polo and its creation is attributed to Paquirri el Guanté although it is related to the soleá de Triana, as we said before. (It will be analyzed with more details in the next chapter)

- ‘Solea Petenera’ influenced by the cante with the same name.

It is important to take into consideration that this is one basic example of how to accompany a solea (in this case, solea de Alcalá). There are other different ways of doing the accompaniment (especially since the guitar started to gain importance with Paco de Lucia) but as a standard, this one can be very helpful to understand the harmony of the soleares.

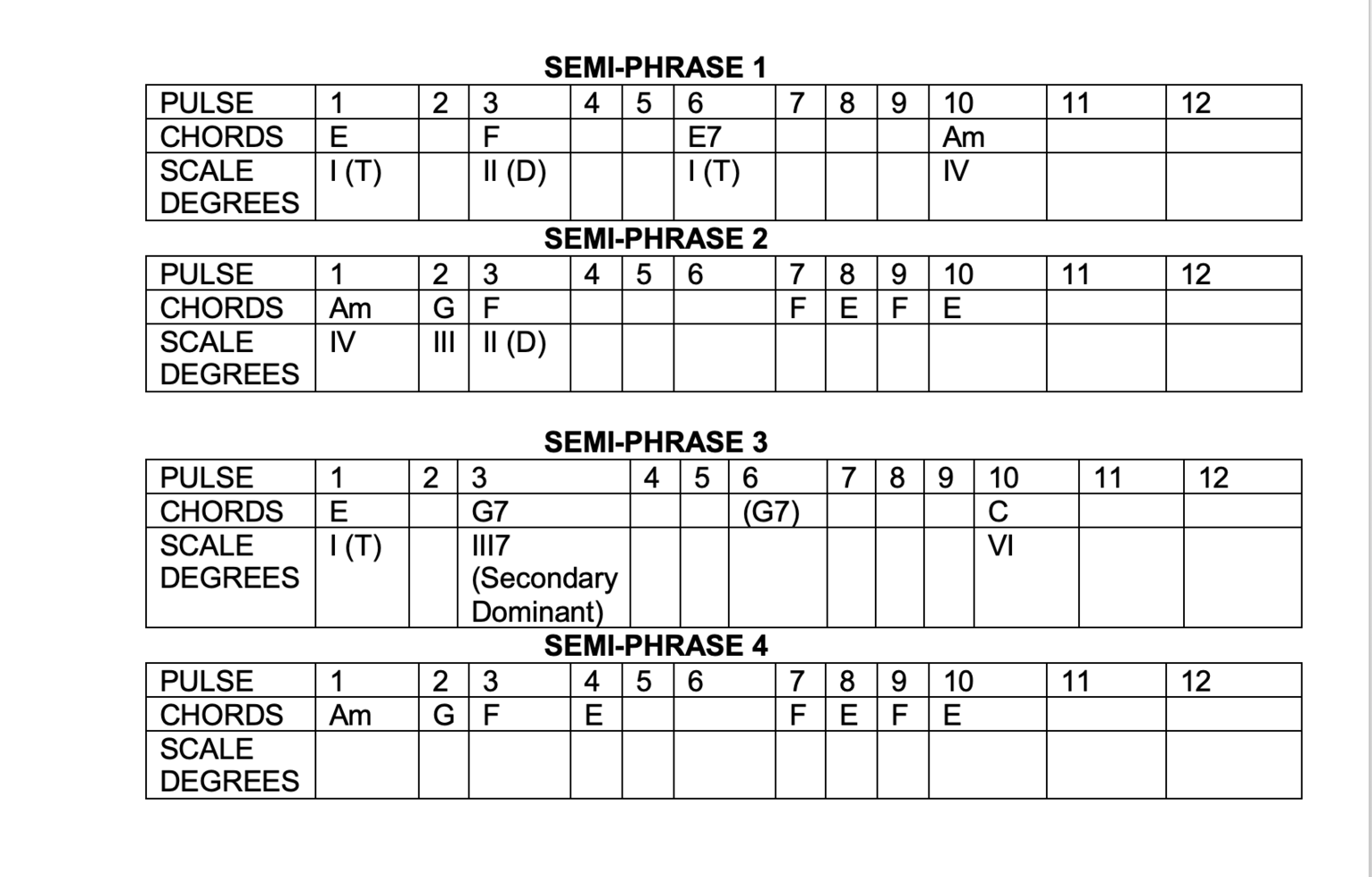

The conclusions are the following:

- Each stanza is divided into four semi-phrases of 12 beats each.

- On beats 11 and 12 there are never guitar chords, so we can say that the phrase ends there and that the two most important beats are the 3 (with the tension) and the 10 with the closing. In bar 12 we can find a slap moment that marks beat 12 and can be useful as a reference for the singing.

- Semiphrases Phrases 2 and 4 bear a certain resemblance since both have the Andalucian cadence (Am-G-F-E).

- Semi-phrases 1 and 3 are similar in terms of harmonic rhythm, although the chords are different. In the second semi-phrase, we find a secondary dominant G7 that goes into C Major, so we could say that even though the soleares are based on the Phrygian scale harmony is also a characteristic in the second part there is a change to the Major.

- We could therefore say that musically is made up of two parts:

A (semi-phrase 1 + semi-sentence 2) B (semi-phrase 3 + semi-phrase 4).

Following the classification of vocal resources of flamenco singers made by Alba Guerrero4, the following classification does not include each and every one of the existing vocal resources, but some of the most used. Others will be found and transferred to the cello as they appear in the various transcripts. Below are various suggestions to imitate these resources with the cello, with the aim of being able to apply them when playing various soleares.

The classification is the following:

1.Vibrato

1.1 Marked vibrato

2. Ornaments

2.1 Superior mordant

2.2 Inferior mordant

'Although it is far from being proven that it is the main cante, the truth is that the immense range of soleares […] contains […] the essence of flamenco art. […] Musically it is based on the Andalusian scale5.’

‘El cante por soleares is considered one of the fundamental pillars of flamenco art. […] Also the mother of cante6.’

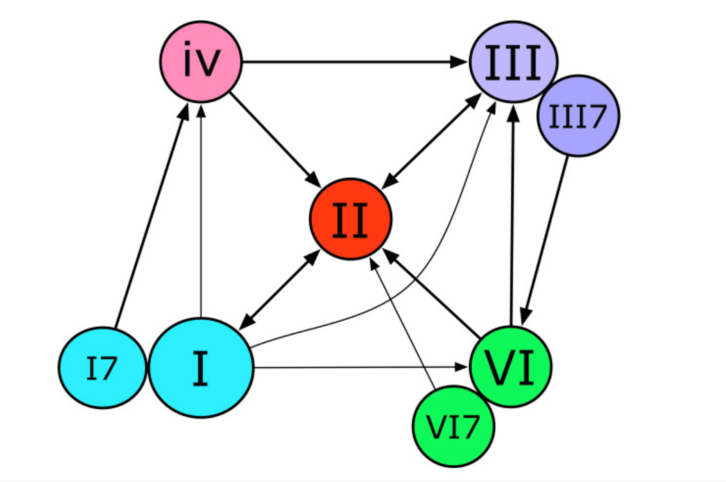

On the other hand, the flamenco language cannot be understood without discussing the famous flamenco cadence, since the chords that form it are essential to the sound that we hear and identify as flamenco, and it is one of the most common patterns in the cantes. This cadence is created by harmonizing the I, II, III, and IV degrees of the Phrygian scale in the following way: Am-G-F-E. It is characterized by the fact that between the first degree E (modal tonic) and the second degree F (modal dominant) there is a halftone, as occurs in the Phrygian melodies of flamenco singing.

These graphs by Faustino Núñez will help us understand the movement and importance of grades: