i see composition as the literal definition “to compose”, meaning placing things together. this means that mediums including sound, theatre, art and media are directly involved in my practice to contribute to the whole work.

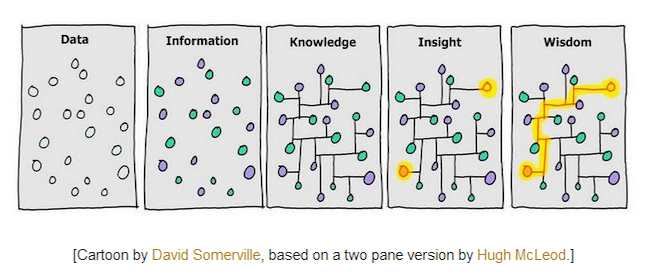

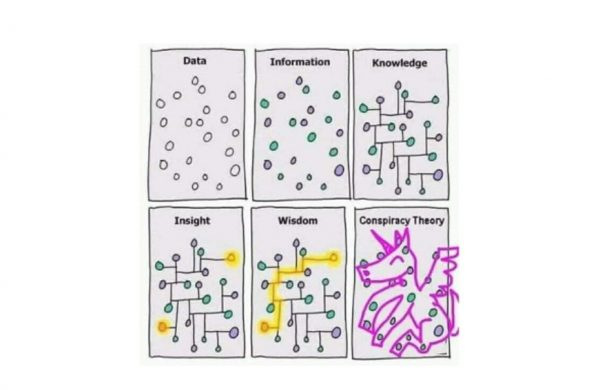

my work as a composer deals with information and data that i then process and disseminate into a composition. however, through processing it i usually find a way to infect that information with misinformation. the accompanying diagram represents how i view this process(fig.1). the work i make is therefore situation and observation based. i make work based on the situation i am in. because of this relationship between situation and observation, improvisation is an intrinsic part of my compositional and performance based practice, as I am processing information about my situation, observing that and providing a response. as a free improviser, this is how i deal with performing with other performers, by observing and processing what sounds they make, and that informs my decisions on how to proceed and perform myself. either i can observe something they are doing and provide something to antagonise it, or something to support, leaving them space to continue, try and instigate change etc.

literature review

my practice and aesthetic are usefully contextualised by several key areas of the twenty-first century canon of music, theatre, art and technology; the new discipline, new music theatre, devising, imaginary musical radicalism, verticalisation, free improvisation, language in music/language as music, internet art and video art, cabaret, sampling and plunderphonics,

the new discipline, a term coined, but not fully owned by composer/performer jennifer walshe (2016) is associated with composers such as neil luck, andy ingamells, elaine mitchner, james saunders and laura bowler. this is born out the work of mauricio kagel and new music theatre (heile, 2017) the new discipline is a blisteringly exciting genre of new music. described by eric salzman and thomas desi (2008: 5) as:

theatre that is music driven (i.e, decisively linked to musical timing and organization) where at the very least, music, language, vocalisation and physical movement exist or interact or stand side by side in some sort of equality but performed by different performers and in a different social ambiance than works categorised as operas (performed by opera singers in opera houses) or musicals (performed by theatre singers in “legitimate” theatres.

new music theatre is music that fully incorporates collaborative and devising methods of making music that fully incorporates visual theatre and theatre that fully incorporates music. i can draw parallels to my own work where in principle the visuals are as important as the audio, and my work is created through devising, shaping and refining what happens in the rehearsal room. in conventional classical music, the score is the dictator of every decision, with conductors and musicians employed to interpret it.

scores are not approached in the same way as conventional music when devising new music theatre. salzman and desi (2008: 34) claim: “notation is not necessary or is, at most, a mnemonic device to remind performers of ‘how it goes’”. without the score, modes of performance drifted into open forms of performance which led to a liberation of the constraining nature of musical notation. in devising with fewer boundaries, the more something devised is repeated the more they start to take on a fixed form.

imaginary musical radicalism (reuben, 2015) is the idea of using once-radical forms of artistic performance and rebellion as protest, as an aesthetic without the actual embodied protest. for example, taking the action of destroying a single violin by nam june paik (one for solo violin 1962), johannes kreidler’s version is hysterical and hopeless by smashing one hundred violins at the same time (kreidler, audio guide, 2014). kreidler has taken the original performance of protest and has repurposed the gesture as an artistic and politically futile event. “their radicalism is imaginary in that they operate within the mimetic barrier of today's contemporary music and art practices”(reuben, 2015). i take a free approach to structure and how i approach performing the material. i disrupt myself by using and embracing actions not normally associated with professional music performance, like; burping, stuttering, falling over, failing and distortion of information. by using these elements of performance that sit outside the normal approach to performance for aesthetic reasons rather than political reasons, relates my performance practice to imaginary musical radicalism.

a new form of sonic composition called verticalisation arose in the late twentieth century through breakthroughs in audio technology (gottschalk, 2017: 159). verticalisation is the layering of multiple audio sources at once to create a deeply polyphonic and complex new sound. jennie gottschalk (2017: 158) describes verticalisation as:

'the density at which sonic information is presented negates the possibility of finding a single path through it and has an initially bewildering effect. it could be likened to being dropped in the middle of a dense forest and trying to find a way out with no guidance.'

what interests me is the multiplicity of information and the potential of how the vast sonic information could be comprehended by the audience. this could potentially be a positive thing rather than a negative. “what initially feels like an oppressive situation becomes empowering” (ibid).

free improvisation involves responding to other musicians freely with sounds and having conversations within sounds to create an abstract performance. this practice has been extended by vocal practitioners to include language as part of their instruments. gottshalk (2017: 175) summarises:

'language itself can be a source of music. there are many methods of focusing attention on the spoken word as organised sound. speech patterns are full of sonic information as they are of linguistic information.'

this duality is something i am constantly battling within my work. i play with the meaning of words and language, while also using speech as a sonic instrument in a free improvisation context. by dealing with both simultaneously, the empirical information within the language i use gets disrupted by my sonic exploration of the sounds of the words.

this technique of using voices as pitch material is evidenced in alvin lucier’s piece, i am sitting in a room (1969), as the voice’s pitch content is revealed through the feedback resonance of the room he is in, gradually turning his words into sound, devoid of language. paul demarinis uses technology to analyse the melodic information within his speech to produce synthesised tones (songs without throats, 2019). in look how/where the lens lies (figure 0) i use a live puredata patch that detects the pitch of my voice and plays the pitches back as sine tones in real-time. i also use certain words for their sound and not their meaning, though this is not made clear to the audience. this aspect creates an additional reference to the genre of sound poetry and concrete poetry. these are vocal performances using syllables and words to create sonic poems of sorts, where the empirical nature of the poem is a byproduct of the words that the performer is using for its sound (gottshalk, 2017: 181). recognised practitioners of this art include tomomi adachi, chris mann and jaap blonk, the latter of which created his own language system which melds several different languages to improvise with (ibid). this is radically different from traditional poetry, where the sounds of the words are usually only used for onomatopoeic reasons, as in to further the meaning of a word with a related sound.

how not to be seen: a fucking didactic educational .mov file by hito steryl (2013) explores how to make yourself disappear in the digital world and is an example of internet and video art about the meta nature of digital work. this work is based in the world of internet art, by using digital technologies, accessing the.mov file online and about how the human experience has evolved with the development of a virtual sphere. this piece also takes the form of an educational didactic lesson, a popular and common form of video on youtube. if you can imagine it, there is more than likely a tutorial video online that will help you achieve that, whether it be cooking or how to set up your computer.

this didactic style can be found in the works of neil luck (bad metropoles, 2019) and matthew schlomovitz, the latter of whom has made several performance lectures (lecture on bad music, 2015). this style of performance is an extension of john cage’s lecture on nothing (1949.) luck uses language and his failed attempts to use words when playing with this role of performer/teacher:

'for me, it's a natural extension of the interest in the body, specifically, the quasi-human/perfect nature of it feels like a foil to my own use of the voice – fallible, pathetic, obsessed with the uncontrollable bits between language, the mistakes. that's why i think the tech is so prescient, a reflection of our everyday corporeal engagement with technology and online media – this slick, polished surface as a distorted reflection of our own messy, flabby bodies. (luck, 2016).'

this style of lead performer, improvising with text, showmanship and stretching into the realms of comedy and music performance stems from cabaret hosts or reciters. these performers’ voices were often untrained and the idiosyncrasies of this voice formed the basis of their performance style. also known as monologists who are described as the following by salzman and desi (2008: 91):

'a type of performer/reciter popular in the cabaret, music hall and vaudeville who reappeared in the latter part of the century as the protagonist of “performance art” performance.'

this style of performance is continued by modern works by andy ingamells, neil luck, jennifer walshe, laura bowler and timothy cape. by using personas to lead narratives in works, these performers perform as themselves but also not themselves, more of an extension of themselves inhabiting a different role or personality (schechner, 1981). for example, laura bowler’s performance as a boxer in walshe’s piece training is the opposite (2014).

sampling is a common process of taking someone else's music and reusing it in another piece. in classical music, mahler would quote beethoven to celebrate him (steinberg 2013), while bartok quoted shostakovich to parody him in his concerto for orchestra (1943). sampling evolved into an exclusive skill to those who would cut tapes together to make new music. now, sampling has evolved to an accessible form of making music through the rise of easy to access and utilise digital audio workstations (max alper, the brief history overview of sampling lecture, 2021). however, john oswald took this a step further by creating works with entirely reappropriated music, often to make a statement about the work he was taking from (jones, 1995). this plundering is soft, as oswald (1995: 87-89) discusses the ethics in his taking of musical material from other artists:

music is information and, as such is a renewable resource, intellectual real estate is infinitely divisible. the big difference between the taking of physical property and the taking of intellectual property is that in the latter case the original owner doesn’t lose the property. they still have it, theft only occurs when the owner is deprived of credit

my use of and interpretation of sampling practices relates directly to internet art because it commonly utilises videos plundered from other sources in a similar way, to repurpose a video to say something the original material was not ever going to say by itself.

for example, in this piece is not about beer (fig.1), i was asked to make a piece for a local sound art festival where i live in stirchley. i was aware of the avid independent beer culture in stirchley, where there is an established pub crawl called ‘the stirchley beer mile’, which stops at eight different bars and breweries. in my piece i obtained an empty beer keg and rolled it to each of these stops, the sound of the keg rolling as tiredly pushed the keg over the mile. in this piece isn’t about teeth (fig.2), i wanted to make a piece about facism and how i wanted us in society to do more about it. i couldn’t quite make that work, and decided to avoid the topic by instead focusing on teeth as an allegory, as i was trying to avoid the guilt of my own inaction.

this piece is not about... is a prefix i use to try and provoke the audience to question what the piece is about. this makes the piece more open to personal interpretation from the audience, rather than prescribing what it is about.

i have what i call a “soundcloud practice”, which consists of improvising music into a d.a.w. and responding to that recording with a new improvised part. very little is premeditated, and is instead instinctual. the results are kept and never nitpicked around with. this offers me freedom of being able to freely make things without being inhibited by an aim or an objective that usually comes with my more “composed” work like this piece isn’t about teeth or this piece isn’t about stock images. this soundcloud practice allows me to make music quickly, in the comfort of my own space, and without the worries of how the piece will be perceived. music that accompanies several videos in this submission was made in this way.

examples of this soundcloud practice can be found as squares of colour palettes on this page. these squares are colour palettes made by myself immediately after finishing the recording of a piece. i improvise choosing the colours that i think suit and reflect the character of the piece or how i feel about it.