Before starting a warm- up

Hello everyone, Let’s come together in a circle Not an oval, not a square - a circle Holding hands And we go One, and two And one back One and two And one back Yes- exactly- great- crashing a bit - perfect I will be talking while we do these steps on the circle One, and two And one back We are here together We will spend the next days here together. Together we will be running, walking and standing In circles Most of us do not know each other We will enter this space as strangers Maybe some of you will become friends during these days But most of us will leave as strangers as well We are sharing this moment together- as stranger A moment Running, standing and walking together And then we will leave - as strangers What we do here cannot be done with one What we do here cannot be done with two or three We need to be many - together Starting here together, in a circle. Holding hands Sharing sweat- a soft way of floating into each other What does this step remind you about? Yeah- a folk dance you feel you have done before- not exactly this one But something like it. These simple steps- repeating They can go on- and on- and on They could have been any dance anywhere at any moment From the start - whatever that may be- anyways- very far back There has been the circle The human, in a circle Around the fire Moving around, celebrating, marking something. Generations before us Far far far back Great grandfathers Ansestors This could be anywhere Anyone At any time By being here right now doing this I like to think of us as a living archive A living archive Tapping into these movements Tapping into the past - very far back And into the future This could be anywhere Anyone At any time This is us, only us. Together This will never happen again This is only us, only now, only here It can never happen again Not tomorrow, not the day after only now, only here, this is only us Together We are a living archive This could be anywhere Anyone At any time Closing eyes Listening to the space to the steps Resting our hands in those of our neighbours Trusting our neighbour to hold our hand Feeling the circle and everyones hands through our sweat and touch. The most formal way to get intimate- sharing hand sweat of our neighbour, With the other strangers in this room Together Slowly allowing our steps to disappear into the ground. Standing Slowly letting go of the hands of the neighbour Opening the eyes Seeing the others Let’s start walking Saying hello with our eyes It is a meeting Seeing for real We see for real We see the other Continuously passing others, passing through openings, like doors which continuously change, open, appear Walking through the openings created by the others, by us, together I can change at any time I can change my direction and any time, I keep seeing The others

All—a physical poem of protest in Portland in 2019 hosted by the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art (PICA) at Pioneer Square, the central city plaza, which is home to civic celebrations and gatherings as well as nationally-broadcast protests spotlighting conflicts between leftist Antifa activists and right-wing white supremacist group, such as Proud Boys.

‘While Portland is a largely progressive city that supports freedom of expression and political protest, it also has a deep history of racism and police violence. If you saw news coverage of the The Black Lives Matter uprisings of Summer 2020 in Portland, you may have seen thousands gathered in the square where All - a physical poem of protest had been a year before.’ (Erin Boberg Doughton

Artistic Director & Curator of Performance)

Rather than writing a chapter about this community piece ALL—a physical poem of protest, I realised I wanted to choreograph a chapter in collaboration with Laurel V. McLaughlin and Simona Koch enveloped by the score of ALL—a physical poem of protest itself. I have approached this chapter as a space facilitating different voices traversing this work in text and image by placing text blocks and images alongside one other as bare material for the reader herself to make the pacing between different modes of sharing/ address.

Despite the increasing privatisation of public space, which is taking place in many countries, public spaces still serve as potential sites for collective protesting, grieving and performing solidarity and care. ALL—a physical poem of protest is born in times of large socio-political movements. The work deals with the question of how to draw the macro political into the body and root it within various local contexts. ALL—a physical poem of protest investigates this protesting body—the human mass and its force—through the meditative actions of walking and running in circles.

This is a project with and for numerous communities of different geographical locations and demographics moving together in solidarity in collaboration with local artists. The poem consists of a mass of local people of various ages, backgrounds and appearances. The participants share their local (communal and individual) urgencies and differences through the power of gathering.

It may manifest as a 45-minute to three-hour performance on stage, an hour manifestation in an outdoor public space, a protest, or… simply a workshop. The performance may be performed clothed or naked depending on context. The piece has, for instance, been used in a feminist protest in front of the National Opera in Bordeaux with activist groups of the city; it has been a used as the union of dance ́manifestation in front of the parliament in Oslo; as a part of the protest “Love-in. Queer action for Chechnya” at the Soviet War Memorial in Treptower Park in Berlin; indoors at Burgtheater in Vienna; at the Dance Élargie/ Théâtre de la Ville in Paris; at the theatre La MaMa in New York; and at Pioneer Square in Portland, to mention some.

The score

Standing in a circle, facing inwards

Every second person turns outwards, one at a time. Take time.

Turn outwards towards your left shoulder.

Soft gaze, looking at the person turning.

Arms up together with the group, take our time.

Hands a prolongation of the arm, feet hip width apart.

Start to lean into each other.

Start to move the circle together.

Fall out of the circle together.

A moment of soft and silent walk in curves around in the space, passing through each other,

looking at each other while passing before gathering in the corner with the group.

All—a physical poem of protest in Portland in 2019 hosted by the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art (PICA).

One person is left alone in the space walking three or two rounds

Person number two walking two rounds

Person number three walking one round

The group supports and looks at the single people walking

The people walking: walk with your intention: for whom or for what are you walking.

Take your time in walking, carrying the space with you, and those you walk for: bring them into the space

-Open gaze

This picture from All—a physical poem of protest in Cologne is taken by one of the volunteers in the piece, a man in his mid-80s. He joined the score for the first time in 2016 in Copenhagen when the score was a part of the piece A song to…, 2015. Since then, he has taken the train from Copenhagen to join as a volunteer in Trondheim, Cologne, Vienna and Paris. In Cologne he brought his old camera.

The transforming body

Borders exist.

The boundaries that are soft, those almost invisible and in the skin, in the body, in the movement, between people.

On stage, in the spine. The negotiation between the vertebrates. The negotiation between the will and the bodies’ own boundaries.

And the hard boundaries. The great boundaries that draw geographies, that are drawn and drawn again by negotiation, war and conflict.

And, that which cannot be negotiated.

In 2002, I saw American dance pioneer Simone Forti on stage.

As she entered the stage I remember I immediately started crying. She became an animal, she became a monkey. Dissolved boundaries between human, animal, object. The transforming body. Repetition, a being behind the cultural body. To resolve the boundary between what one sees and what one thinks one sees, between genders, the prejudices and the limitations in how one sees the other.

Much later I read about Fortis’ observations of animals in zoos that started in the Rome Zoo. In her observations of polar bears and elephants repetitive walks back and forth inside their enclosures, she writes ‘I remember first watching the polar bear swinging its head.... It seemed to me that the bear was taking care of itself in a way that I could understand... That bear, whose genetic makeup keeps it ranging at great distances over frozen lands, was in a small enclosure in the Rome Zoo... In every bear, gorilla, or person, there's an ability to retain the essence of one's nature regardless of how much the pattern of one's life system has been fractured or taken away.’

Professor of modern and contemporary art history, Julia Bryan-Wilson wrote in 2015 about Simone Forti’s identification with animals in the zoo: ‘Rather than turning to animals for a model of “natural” liberation, Forti came to them out of despair, a shared sense of dislocation, loneliness, and isolation. At the same time, she did not neglect their adaptability, attending closely to their moments of connection and collective recreation. She was constantly aware that their movements were shaped not only by their state of captivity but also by their inner reserves of strength. She mentions, for instance, “the big cats compulsive pacing at the fence, which seemed to provide a modicum of relief,” and writes that it gave her “a new view of what it was that I was doing when I was dancing.” Movement is, for the animals as well as for her, a method of control and redirected awareness: “At times I've escaped an oppressive sense of fragmentation by plunging my consciousness into cyclical momentum.”’

I have since understood that what I recognized in Simone Forti’s body on stage in 2002 is something I worked on for many years in my own body and practice: the repetitive movement that dissolves boundaries and limitations that some states and situations carry with them.

Everyone in with last person walking alone

Take time for walking

One person initiates the running which installs the different speeds

Allowing radar to exist for a while with the different speeds.

Make sure we keep the different lanes of speed.

Move faster than the ones on your left shoulder, move slower than the ones on your right side.

Use your face and head to look at the others.

Keep your gaze away from looking down.

Soft and silent walking and running

Run with the ball of your foot, not heel first

TThe artists Jeremy Wade and Jo Koppe borrowed the score as a part of a protest; The walk of solidarity “Love-in. Queer action for Chechnya” at the Soviet War Memorial in Treptower Park in Berlin in April 2017. This protest was in solidarity with LGBT people in Chechnya.

Political marches begin with footsteps, with repeated and multiplied rhythms of sound and social bonding. As the most primal form of human locomotion on land, walking is a spatial method by which people make their opinions on the dominant political order into a public event. Dominant political orders are also manifested in our built environment. Buildings and monuments—designed by architects, planners and policy makers in an endless process of production—define and change our landscape and establish a spatial array. This socio-spatial array forces us to adjust to particular social contexts, behavioural codes and political regulations. But at the same time this spatial array also provides us with a space in which to negotiate, oppose and resist—a stage.

All - a physical poem of protest in Portland in 2019 hosted by Portland Institute for Contemporary Art (PICA)

Everyone leaves radar into standing in a circle face facing inwards, standing in silence for a long while.

Filling the circle with your intention and listening to what is there, the energy generated.

Stand in a position which feels good to you in that moment of listening.

No need for equal space between each performer.

You can stay close to someone if you want.

Research lineage: HEAD(S)—A song to….—ALL—a physical poem protest

1. HEAD(S)

Laurel V. McLaughlin: ...How did this this work come about, and how has it manifested in other spaces?

Mia Habib: The work originates from another work that premiered in 2015 named A song to…, where we worked with 16 professional dancers and 30 to 50 extras. So, we were about 60 people on stage. That piece for me, began when I was living in Tel Aviv when I was doing an Masters in Conflict Resolution and Mediation. And this was at the same time when the Arab Spring started and the Occupy movement began in the United States, and in southern Europe there were protests there. So, in the summer of 2011, the protests started in Tel Aviv for social justice. It was a special moment because it was the first time that Israeli society openly said that they were positively influenced by the Arab world, and inspired to protest. So, people were out in the street and it was interesting to see how the protest turned into spectacle. And there was this belief that by being together and doing together, we can actually change something. There was this energy going on and I got interested in that energy created by the mass and bodies coming together in a physical space. This is especially true in the Arab world where you leave your house and there is an urgency to meet and be together. This energy, then, is possible in a mass and is not possible with just a few bodies alone. I was fascinated in questioning what can a theater be, and then a performance, what space can that have when what’s going on outside is so powerful.

So, I started to work on a solo work at that moment, of trying to see how I could use what was going on with this energy that was going on outside and move it into a small theater. Then I was wondering how I can I find some ways of working with this that would create energy when the protests were over. That turned into something I called a mass solo, where basically it’s a solo that begins with one body in a two-space theater—there’s a stage and there’s an audience—and then it ends up being a one-space solo where the performer’s body is gone and the audience has taken over the performance. It’s called HEAD(s). With the terror attack on the 22nd of July in Norway and from afar I saw these thousands of people coming together in public space and grieving, so I shifted my focus into the power of mass, coming together in public space not only for protest, but the urgency to grieve together when the collective grief is, in a way, personal and collective, and they

Research lineage: -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------HEAD(S) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- A song to...- --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ALL- a physical poem of protest

“Larvatus Prodeo”

Jassem Hindi

There is something frightening and dangerous about a single body moving in front of a mass of people. Something is exposed.

And yet, by Descartes word: larvatus prodeo—she comes forward, masked.

Something starts inside her body. An autistic song at the edge of her skin. And then, like a distorted ritornello, something resurges which could belong to anyone. Which could have been sang or danced by someone else. In the horizon of this dancing body, signs appear, fragments of masses which haunt her, and come to us, slowly, from behind the mask. We are being hosted by a single body.

A masked solo to seduce the crowd, to protect the body, to create a distance - to generate irony and make the crowd laugh. A mask as one bright frontal surface, a mirror that would tell you that everything is fine. Yet this puppet-like figure is also—of course—the puppet master of the evening. The inherent opacity of her body is a deceptive surface, hiding and revealing other opacities, other masking operations.

It starts with a single body. An idiot’s body. Singular and displaced. Something laughable and charming, something that would lead us to catastrophy if we let it run the world—took her seriously for a minute. Something which points at the idiot in us. A glorious destructive smiling idiot. And back again, from the idiot to the crowd, from the crowd to the idiot.

And yet, a mass solo is also about a body that let’s itself be invaded. Mia lets the crowd come to her, almost into her. Politically, socially, intimately. A high risk for a single body: to be given to an unknown crowd. To invert the laws of hospitality and of public theater: her house becomes everyone’s house—a radical operation.

But also a perfect cache: hide it where everyone can see it. To reveal her body as just one of many. Suddenly the idiot multiplies and she fades into a shimmer of masks, faces, costumes. The crowd becomes the masking body. An opacity of sound, opinions, rushed decisions. A crowd: body that generates a space of its own, recreating everything, disrupting the timeline that was initiated by one.Research lineage: HEAD(S)—A song to….—ALL—a physical poem protest

2. A song to...

Mia Habib: So, while working with the solo, I realized that for the next piece, I wanted to start with a mass on stage. That was the beginning, which led into A song to…, where I felt that a mass could be 16 dancers on stage. Then while we did some auditions and at one point we had about 50 people running on stage, and I was like, “Oh wow, we need at least 50 people to get this feeling that there could be hundreds or thousands more together.” This was the emerging points, the energy, the protesting body, and this ping-ponging between the singular and the mass, led us into thinking about the mass as being monumental. It’s so big that somehow the human is erased, so in looking at the monumentality of the mass, I also started to work on monumental body ideologies, and how these ideologies from the ‘30s and ‘40s, such as the New Soviet man, the New Jew in Zionism, the Übermensch in Nazism, are these bodies that cannot be defeated. These ideologies that are coming back into focus. I think there is a way to touch these body images and crack them up somehow. There is a park in Oslo called the Vigeland Sculpture Park, and it opened in Norway during German Nazi occupation. It opened in the ‘40s and it portrays the monumental moments in life, like birth, death, aging, through these sculptures that portray the body ideology of the time. I worked with this question of: what would this park look like if it were made now? In a way, even though it’s stone, it’s white bodies portraying an older version of Nordic identity; so what would it look like if we worked with that information and really wondering what is the vulnerable body? What does the multiplicity of bodies mean? What about different bodies that are in the world, and what happens if those bodies build these monoliths that are so different from those from the ‘40s. Because this park is really seen as the jewel of our national heritage. That’s a lot of information, but those are the strands that came together for it. And the end of that piece has a score that could go on forever, and it’s basically an ongoing—we call it the “radar”—and it’s a spiral that could keep on going for a long time. Doing the end of that piece, that’s going to have the potential to generate energy and people both doing and watching it have very emotional reactions to it that can only happen when there are a certain amount of bodies. So, I chose to isolate that score and make this into the piece we have here now, which is ALL—a physical poem of protest.

Research lineage: HEAD(S)—A song to….—ALL—a physical poem protest

3. ALL—a physical poem of protest

Mia Habib: And the title, in some places works and in some places is maybe provocative like, “who is all? What does that mean?” In some ways, I have a problem with the title and I’d like to keep it that way. It doesn’t add up in a way. What for me is very exciting with this work is the fact that the work changes depending on every place in which it comes in contact with. For me, it’s research. It can be 10 minutes long, or for longer. Here, we’ll try it for 3 hours at PICA. So one, it’s the duration. The second, is the placing of the audience—we’ve done different things, looking frontally at the work, around the work, or seated inside it. And third is place—it can be in a gallery, as part of a protest, and then in other public spaces. We never know the work before it happens; so, in that sense it’s a premiere each time. It touches an urgency that occurs in public manifestations. You know, you don’t rehearse public manifestations—you can facilitate. You’ll see, it’s quite formal, with a clear shape. That also relates to calling it a physical poem—creating this distance to think about what a public manifestation can be. But within that formality and pre-set score, there is real-time negotiation with those that are participating. And I will say, that it is really a negotiation of difference, because we are gathering people who we don’t know in advance and many of them don’t know one another. Even though we follow the same directions of walking, running, standing, we walk differently, we have different perspectives of speed, and we take information differently. So there’s really a real-time negotiation between strangers of doing this together and accepting that we do it differently, but allowing ourselves to build this energy together and engaging in something bigger than ourselves. And then we leave each other, and we’re still strangers to one another. We still don’t know each other. That’s very interesting in looking at public manifestations. There’s this huge emotion and belief that the world can be changed in a second, and then we leave each other and that was it somehow. Of course, change can happen, but in that moment, it’s something else. This is what I’m hoping the piece can tap into.

One person starts walking in the circle. Slowly people join.

Take time for walking

One person initiates the running as in all Radar I.

Slowly starting to use the virus. One person initiates it.

Virus means that we can touch someone's shoulder or upper back when seing or feeling such a touch.

Accompany someone as long as you wish.

Leave the virus when you wish.

Continue to use your gaze to meet the other, look at the other.

Virus ends when we see someone standing in the outer circle.

‘...walking politics of protest is a very basic tool for citizens to temporarily break free of individualist constraints and to resist and suggest collective counter-position. This temporality, however, has consequences. As Elias Canetti puts it:

Only together can men free themselves from their burden of distance; and this, precisely, is what happens in a crowd. During the discharge distinctions are thrown off and all feel equal. In that density, where there is scarcely any space between, and body presses against body, each man is as near the other as he is to himself; ...But the moment of discharge, so desired and so happy, contains its own danger. It is based on an illusion; the people who suddenly feel equal have not really become equal; nor will theyfeel equal forever. They return to their separates houses, they lie down on their own beds, they keep their own possessions and their names.’‘Understanding space as both a material and social construct, I would like to draw particularly on the act of walking, one among the many dimensions in the choreography of dissent and demonstrations–a strategy by people manifest their ideology in public. Distinguishing this act from perambulation movement on land, I name this act the choreography of walking politics.

The walking politics of protest is an opinionated and planned ideological action with significant spatial attributes–opinionated because walking politics is an action that expresses a conviction of wrong or injustice. Since protesters are seen as unable to correct the situation directly by their own daily efforts, this action is intended to draw attention to grievances, to provoke the taking of ameliorative steps by some target group. As such, protesters depend upon a combination of sympathy and fear to move the target group to action on their behalf.’

ALL became a part of this feminist protest in front of the National Opera in Bordeaux as a part of the ‘Déprogrammation’ festival at La Manufacture Atlantique, 2018.

Everyone leaves radar into standing in a circle face facing inwards, standing in silence for a long while.

One person initiates that.

Filling the circle with your intention and listening to what is there, the energy generated.

Stand in a position which feels good to you in that moment of listening.

No need for equal space between each performer.

You can stay close to someone if you want.

Protest as choreography

Choreographic principles (add photos here as we get the copyright)

The score consists of the meditative action of walking, running and standing in circles. It is an ongoing insistence on exploding the space with the only action of running and walking bodies into several climaxes inspired by Hatuka’s term ‘Choreography of Protest’. A guiding question for this score is ‘What is the ecstatic energy of a mass of bodies in a (performative) space?’. The piece consists of a durational insistence of one living system (the radar) in the space through a real-time mediation of strangers (the participants). In some editions of the piece (depending on duration) the audience gradually becomes participants as well. The score is accompanied by voice. The participants form a drone choir, going from low drone humming into a loud drone scream.

The principles of walking, running, standing and use of circles can be found in various forms of public manifestations and protests:

Vertical movement/stasis/ standing

1. The Tank Man from 1989, is an unknown Chinese protester who stood alone in front of a column of tanks on Tiananmen Square calling for an end to violence and bloodshed against pro-democracy demonstrators.

2. The Standing Man from 2013, is the artist Erdem Gündüz, who stood quietly in Istanbul's Taksim Square as a protest against the conservative government of Erdoğan. His standing provoked a silent struggle across Turkey for the right to protest.

Marching/ linear movement

3. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, 1963. The March sought to address the conditions under which most Black Americans were living at the time. It was before this gathering that the day’s most prominent speaker, civil-rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech.

4. The asylum seeker march was carried out in Norway by 45 Afghan asylum seekers and refugees and their allies in 2007. The march followed the old pilgrimage route from the historical church Nidarosdomen in Trondheim, Norway all the way to the parliament in Oslo marking the one year anniversary of a 26-day hunger strike the year before protesting Norway's policies on returning refugees back to Afghanistan.

Storming/ running

5. During the Arab Spring and the so-called 15 May events 1000 Pro-Palestinian protesters stormed the border from Syria into Israel in 2011. One protester made it all the way to Yafo and had a coffee at a shop before he was arrested.

Circular movement/ centripetal force

6. Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, 1977. During the military dictatorship in Argentina it was illegal to stand in a group of more than three people in a public place because it was considered a potential protest. But this did not stop the mothers who had their children taken from them in the night. They began to walk around the Plaza de Mayo in a circle, white scarves on their heads. These meetings of a few women turned into a ritual that is still practiced in the square today.

7. ‘Liberated Gwangju’: Protesters gather at the roundabout in front of Provincial Hall in Gwangju, May 26, 1980 which marked the first step of the overthrow of the military dictatorship in South Korea. ‘The roundabout organized the protest in concentric circles, a geometric order that exposed the crowd to itself, helping a political collective in becoming’.

8. Tahrir Square, Cairo, February 2011 during the Arab Spring: ‘These images became the symbol of the revolution that led to the overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak… described by urban historian Nezar AlSayyad as “Cairo´s roundabout revolution”’.

Examples of choreographic principles from protests and manifestations not used in ALL:

‘Taking the knee’

9. The Black Lives Matter (BLM) political and social movement has been around for years but gained further international attention during the global George Floyd protests of 2020 wherein millions of people in the U.S. and beyond protested against police violence toward Black people. A common gesture of protest in the BLM protests has been ‘Taking the knee’. The gesture can be traced back to a widely-used image of Martin Luther King, Jr. taking one knee while in prayer at a civil rights march in 1965.

Sitting (sit-in)

10. The 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests, also known as the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement: Pro-democracy protesters, 2019, held amongst other places a sit-in in the arrivals hall of Hong Kong's airport.

11. The 2011 Israeli social justice protests were a series of demonstrations in Israel beginning in July 2011 involving hundreds of thousands of protesters wherein several of the protesters started living in tents in the street. One example are various sit-ins at tents in Rotchild boulevard. On one tent wall it was written: ‘Rotchild, the corner of Tahrir square’ as a sign of solidarity to the Arab Spring uprisings in neighboring countries.

Horizontal movement/stasis/lying (die-in)

11. ACT UP protesters did a die-in on the Champs-Elysées in Paris, France, on Dec. 1, 1994. ACT UP—the AIDS Coalition To Unleash Power—is an international, grassroots political group committed to direct action to end the AIDS crisis. The group was formed in New York in 1987 and is still active.

12. Extinction rebellion protesters have staged die-ins in various places, both indoors and outdoors. Extinction rebellion is a global environmental movement using various non-violent forms of protest and civil disobedience, with the die-in form as one of them.

Picture text: Performing at the International student festival in Trondheim in an old circus manège.

In the first round, there was a belly. Big, round, enormous. A nearly perfect sphere, the globe seems to be pulling the pregnant woman forward, one step at a time. She has a slow pace, and a confident stride. Her body is not stiff and her head is held straight. Her gaze, inwards and outward, is steady. All eyes are set on her. A feeling of fullness, of obviousness, of naturality that one can only regret to have forgotten. The belly seems to finish a second round and vanishes temporarily from sight when a man replaces her.

Skin as interface

With the nudity in the piece, it’s not about the nudity. The mass becomes abstract when you zoom out, it has a shape, then when you zoom in you see the different individuals. In the zooming out, it has this unifying, mass of lines and movement. The most unique we have is our bodies, but there are other social codes and layers that we add onto it. The body is then like a projection screen where, through this repetition and ongoing insistence on this one score, for the audience there are many associations with which to travel when there are naked bodies, such as schools of fish, abstract lines, images of naked bodies—some of which aren’t pleasant historical images. But it’s this flow of association. In France when we did it, we had Kurdish female activists. And nudity there would’ve been an exclusionary choice. So, in some cases it makes more sense to be clothed, to be more inviting to more people.

'Rather, this process of coming-to-know evokes empathy: for the surgeries that have left their marks, the uneven distribution of body weight, for the necessarily fluid spectrum of gender, the endless variations of skin tones for the personal narratives embedded in tattoos.' (Lucy Cotter, Mia Habib TBA Festival / Portland)

https://flash---art.com/2019/09/mia-habib-tba-festival-portland/

One person starts walking in the circle. Slowly people join.

Take time for walking

One person initiates the running as in all Radars.

After a good while in the radar the drone choir starts:

Going into humming and all the way up in max volume with drone choir.

-Starts with humming on the verge of listening with closed mouth.

-After a while, allow the humming to grow in intensity

-when volume pushes the mouth to open go to MO with the mouth.

-Open mouth gradually as volume increases: getting towards max volume with MA in the mouth

and very large open mouth. (The open mouth also creates an image).

-When breathing in on max volume: keep your mouth open to keep the image.

-After max the group finds the low humming together.

-As soon as we are all in the humming: let it die out.

-Always listen to the others and follow the growing of the volume together.

-Use your mouth as a speaker to project sound to the others. A way of sharing sound and

energy together.

-Imagine we are all in one pitch. Sometimes we need to change pitch to increase volume.

Always change pitch on inbreathe, never slide on the pitch while making sound.

-Overlap your breathing with you neighbours, we are trying to create one continuous drone

without hearing the breathing.

-Imagine your head, mouth and throat as a cave of infinity releasing sound in a relaxed way.

-Do not push the sound out, that will hurt our voice.

A real-time negotiation between strangers

Laurel V. McLaughlin: ...I’m curious about the language that you use in the title that you mentioned. Could we return to what “ALL” means or embodies for you? I use both terms in the dual sense that Susan Leigh Foster does when referring to social choreographies—in that we cannot parse thinking from the body, or physicality from thought.

Mia Habib: If you think of the physical aspect of it, when we did A song to… my initial idea was just, “we need 50 more bodies on stage,” and I thought, “Oh, they should look different,” as if the body and who the person is are different. Then when people arrived I thought, “Oh, it’s people, with histories, who talk differently, take space differently, move differently, have different communities, have different conceptions of society.” And slowly, that took over for me, who people are, rather than what it looks like. Through doing A song to… in different places, we had some amazing experiences that, in the beginning, was just a default. In Germany, for example, we had a homeless man and then a former policeman running and walking together and we didn’t realize until after. We had priests and performers, and then those that are isolated from people. Somehow there was a large variety of backgrounds of people and how they function in society. That became important. Then also how people negotiated the space. And then also bringing in people who perceive the world and information differently, like someone who is 55 but lives at home—but not to point this out as different, but finding a way of facilitating the group—to find a language for everyone, rather than doing something special. So, in that work of negotiating difference and creating space that wouldn’t signal out people, that became the methodology. Bringing in the word “all” became about who can that person be. In the world of dance, when you have different bodies on stage, I hear my colleagues saying, “wow, it’s so diverse.” And I say, “What do you mean, ‘diverse,’ when everyone on the stage is between 25 and 35, and just because they look a little bit different—what is diversity? It doesn’t take much before we say, “Oh, they’re all on stage.” But I think no, which bodies aren’t on stage? So, I thought bringing this word “ALL,” makes you think of those that aren’t on stage, because there is always someone who is not on stage. You will never get everyone on stage. How wide is that idea of who that can be? Also then, when it comes to nudity, since we’re naked on stage—there is this thing in dance that even within dancers there are certain bodies that are more easily undressed on stage than others’ bodies. In a way, we should be past it but we’re not. There are still questions about what dancer’s body should look like. You can be trained as a professional dancer all your life, but still not look like some idea that people might have. With the idea of a dancer or body in general, there are so many bodies that are hidden, or choose to hide themselves because of this pressure from society. That’s important in this work—not pushing that, but allowing it. Then to take the problematic side of it—an example of the failure of it in a way—was when we did it in Paris. We had to find the volunteers in Paris ourselves, but the outreach part of it wasn’t strong enough. So, we ended up with mainly only white bodies on stage. And in the European context, Paris especially, has had many protests concerning how non-white bodies are treated. You cannot, not anywhere, and especially not in Paris, come and show a piece called ALL – a physical poem of protest, and only come with white people. That’s not acceptable because it reflects society. In a way it becomes a mirror of a society, but on the other hand, in that sense the title was problematic. I wanted to cancel the piece, but it wasn’t possible. In retrospect, I really thought about how you maneouver that. I don’t have an answer, but it’s to give an example of when the title is a bit dangerous.

Warming up before performing in Burgtheater, Vienna, 2020, during the programme EUROPE MACHINE curated by director Oliver Frljić and the philosopher and activist Srećko Horvat.

Real-time listening as a tool

Laurel V. McLaughlin: This notion of collectivity begins in the workshop phase, so could you share your working methods and strategies with the volunteers and your collaborators Jackson and Noonan?

Mia Habib: Before we start working, we lay out some rules, which worked out great since Physical Education read them out loud, so it almost became kind of a performative act, which I thought was really nice. In a way, it might feel a bit strict to start by mentioning rules, but it’s a way of setting up a safe space and protecting people from each other, so that they can really feel safe. It’s simple rules about what’s acceptable and what’s not in the space. Then, what we do is that we work in a circle from the beginning and do something that might look like a folk dance step, and we talk while we do this. I talk about the piece a bit. This holding hands, creation of a circle, and talking, is about how we can only do this together—it’s not possible to do alone, or with two, or even, I would argue with three. Then part of it is also that when we do this, we will always step on someone’s feet. It implements a space of “it’s okay,” we’re not here to do it perfectly or synchronize it, but we’re opening spaces, and taking down certain nerves in the space. Slowly we work through the different elements in the piece. Sometimes we try to give as little information as possible so that it’s more through doing, and slowly, for the group to grow with it. The main tool we work with is listening. So, if you can listen to the group, you’re good, and you can just do it.

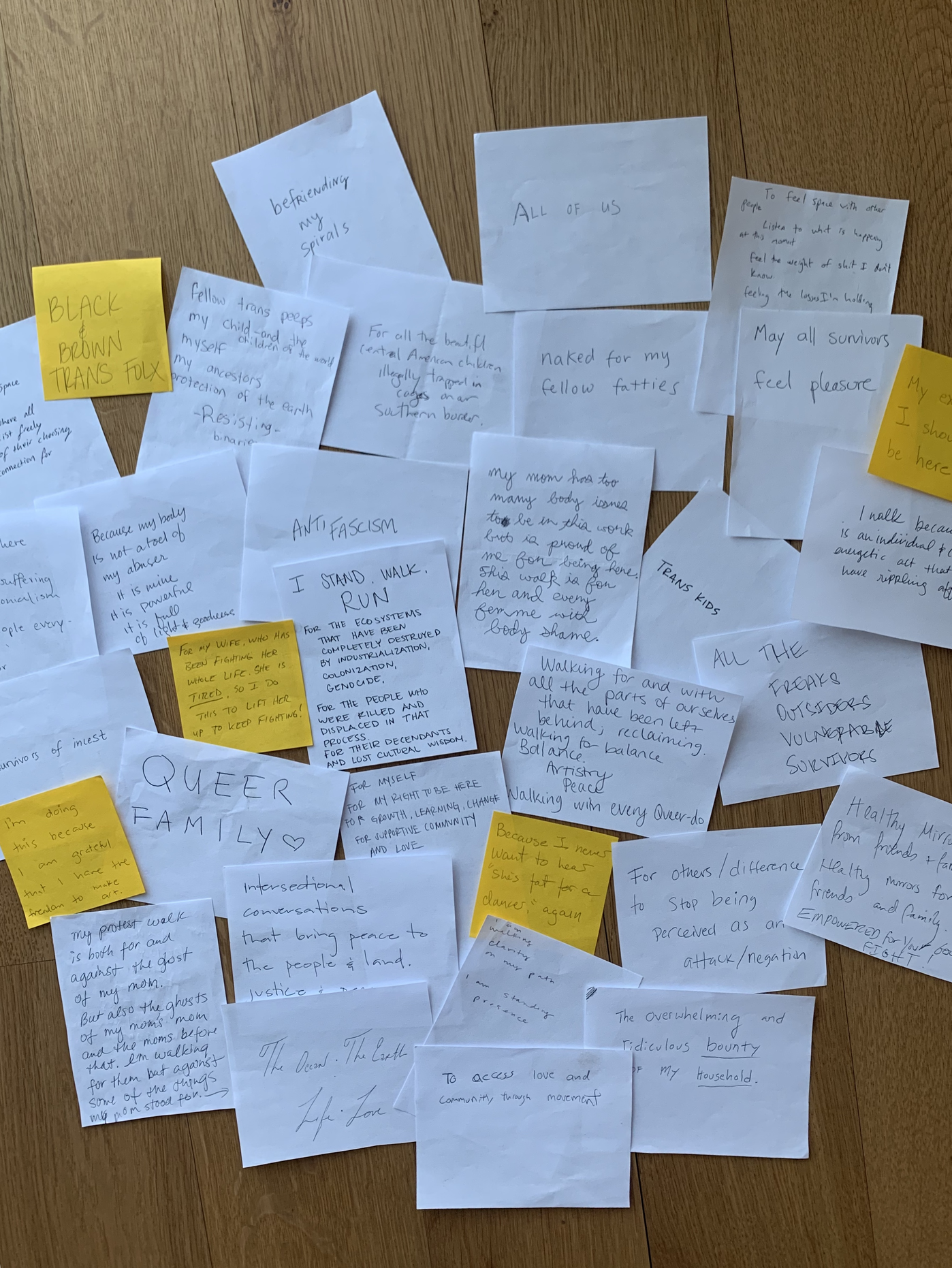

Notes from the participants.

An important part of this process is the aspect of care and solidarity. A guiding invitation and question to the participants during the piece is: For whom or for what do you stand and walk? What is your urgency?

This is a way of rooting the collective and group work back into the individual urgency and for the work and process to be able of hosting and housing different histories and causes simultaneously. One way of doing this is to invite each person anonymously to write down for whom or for what they stand and walk. Then these notes are shared (if agreed upon) and read by the collective just before doing the score. While walking and running there is a resonance of multiple intentions fueling the group and silently touching the audience. In a strange way the consciousness of the group, now knowing the multiplicity of intention, makes the solidarity stronger.

Wherever we have performed “ALL” the volunteers stay in touch afterwards. Some of them travel to join us in other places to perform again, or to watch. Some of them started dancing afterwards, some say they came out of a period of depression, others made a performance about this performance. Some founded a family together. And for some being naked in a public space is an act of protest.

Excerpt from volunteer Shiloh Hodges´ reflections after performing ALL in New York.

Mia reminds us that we are walking and standing for something. A process constantly ongoing, but heightened in this work. I consider the generations of queer ancestors and siblings that have not been able to walk in public as themselves. I consider the danger of walking in public as a person of color. Different bodies experience the vulnerability of public space in different ways. For some, it is a place where power is exercised. For some, it is uneasy. For others it is quite dangerous. To perform naked on stage in New York is still to propose your being in a public space; riskier for some than others.

As we walk through the space I am reminded that we are not walking alone. We are walking with the past and the future that each of us carry individually and that all of us carry together. I am bowled over by my privilege. No matter how tired my legs are, I’ll keep walking.

Volunteer Heidi Steen Jensen who gives an interview to the Norwegian Breast Cancer Association:

Recently she participated in the dance performance ALL—a physical poem of protest. It is about everyone being different with different shapes and bodies. In parts of the performance one should be able to be naked.

-It does something to the audience when they see the nudity on stage. People are so touched and forget that there are naked bodies. You see yourself as in a mirror. It is beautiful in its naturalness. I want to show my asymmetry, which is a part of my life now, says Heidi.

-All bodies have their beauty. The aesthetics are much more diverse.

It feels both significant and meaningful to be part of the performance. It confirms her new body ideal. It has also been wonderful to get out of the cancer bubble, which has only been about her and the disease. She is grateful that she is able to participate, even if she gets tired.

Volunteer who chose to participate in New York, Portland and Vienna:

This opportunity to get to know different artists, and different bodies, and different languages while moving in a very short period within one week is so exiting to me. I love the challenge.

Volunteer in ALL:

As we are all being called to stand and walk for and with the Black community; I have been thinking of ways to continue the conversation and bring people together to walk, to run, to feel community, to heal. And All keeps coming into my mind.

Excerpt from Pour la liberté… written by volunteer Hypo after performing in Trondheim, 2009. Translated from French by Hypo and Jassem Hindi..

To each their own circle, to each their own rhythm, to each their own intention to set radars on the stage.To each their reason today to set the stage in motion. To each their memory of the salt march, the long march for civil rights, for equality and against racism, the march of the widows of asbestos, the gay prides, the march of yesterday or of the day before yesterday, today’s march of the yellow vests, of those showing their solidarity who are arrested and questioned, the march for climate, for farm animal welfare, for trees and for plants, against the extinction of insects, of fowls and any other species. March, we march, you all march. Alone and together. She marches and he marches. For those who cannot. For us. For all.

Volunteer who participated several times on different continents:

The piece helped me transition into a more vulnerable place and a more accepting place with myself. I felt like I had more of a responsibility to take care of myself and to do the things that I really want to do.

Chorography as a political and social practice

Laurel V. McLaughlin: Turning to this idea of protest, which is also in the title, I read that some of your operative concepts for the workshop are notions of plasticity, mobility, site-sensitivity, and soft borders. Thinking of these ideas and hearing you speak about the work, it seems that ALL—a physical poem of protest carries much relational weight that then affects the political and social realms and I’m hoping you can elaborate upon this directionality.

Mia Habib: I think this comes back to the practice that I’ve developed over many years in other works, through insisting on an action or physicality, this develops a micropolitics. Through this pointing at something political through a very clear or simple action or intervention, which for me, always comes through a body, but maybe from the outside it’s not always apparent that it’s from the body which is there. It might trigger or reveal some power structures that are already happening outside. A very obvious example would be my work from 2007 with two other artists that’s informed a lot of what I do—it was with Swedish Indian dance artist Rani Nair and French Palestinian artist Jassem Hindi—on a project called WE INSIST. I still work with Jassem Hindi on a project called Stranger Within, but one of the things we did was make a mirror installation on the border of Mexico and the U.S. in 2009. It was in Mexicali, and we thought that we were going to do something with our bodies, but when we were there we wanted to another kind of intervention. So, we put these 3-meter high, 6-meter wide mirrors on the border wall, it look as if there was a whole in the wall, with the image being distorted because there were different mirrors. That was the installation, but it was more the act of making it and what happened around us in making it that was important. Even though we had a permit, I remember this moment when I was hanging over the fence to drill from the American side, the American border police came in a helicopter and hung over me. They wanted to show that this was not okay, even though we had a permit. From this action, we got in close contact with the neighbors and we also saw these professional jumpers crossing so that others could do that too. It started conversations for the people living there. Our presence created a kind of third party—like a mediation or stretch—where people could talk about something in a slightly different way. This is something we’re exploring in different ways—Jassem and I just did research in the north of Norway where we traveled in a camping car and we performed in people’s houses during dinner. So, we perform and they cook for us and then we eat dinner. We come into the house and the performance is always on the verge of the unknown, or an uncomfortable place for the people who invited us. It’s kind of unsettling. Then during the dinner, because it’s unsettling, it opens space for completely other conversations. In one house we started talking about witch burning after 5 minutes into the dinner. So, it’s this working with opening spaces where other conversations can appear. So to answer your question, it begins with a micro interaction that can open something which touches macropolitical or social questions. Then, sometimes other works begin with the big questions, but they’re all concerned with the physical somehow.

——————————

The We Insist mirror installation in Mexicali, 2009, as a part of the artistic programmation programmatic of Gilead Ben Ari, Running Into the political Equator.

‘The ‘Political Equator’ is a term coined by Teddy Cruz to refer to a phenomenon of an attempt to separate the ‘First’ and ‘Third’ worlds by the erection of walls. In this reality the mechanisms of dealing with socioeconomic problems is through a process of avoidance. This process creates a fragmentation of the society on both global and local levels, in which social problematic elements are encapsulated and isolated from the ‘healthy’/‘functioning’ body of society. These politics of separation are operating on both national and private levels and are manifested amongst other, by the fencing-off of borders, the construction of detention camps for illegal immigrants and the construction of gated private communities.’

Stranger within, Jassem Hindi and Mia Habib, doing their practice, Dance against food, performing in people’s houses in exchange for a dinner. Dance against food was a project initiated in the 2000s in Morocco by choreographer Taoufiq Izzidiou under the name Danse contre nourriture. He then very generously allowed us to use this framework, and we have been doing so for years, and around the world.

The Radar continues in silence after the drone choir is over.

After a while come into walking in the radar.

Slowly turn down the speed of the walk till we come to a standing for a long while.

Whenever you feel ready, start leaving the space, one by one.

Let the space be for a long while, just standing, feeling what circulates. Then leave.

Comments:

For every show, think for yourself for who or for what you want to run, walk, or stand. What is your urgency today! What is important! What do you want to bring into the world.

Remember that people can look at each other while being in the radar. Eye contact, accompanying.

Throughout the piece: Keep soft feet and a loose neck.

We are sharing our energy with the space, with each other and with the audience!

Let’s walk and run with care for each other. We do this together!

Enjoy, this moment will never come back…

Choreography as a poem

Laurel V. McLaughlin: And, what does a ‘physical poem’ mean to you?

Mia Habib: I think that for me, there is something about the piece being only bodies—there is no sound—only our breath and feet, and repetition. This relates to something I didn’t mention yet, but the locomotive of protest is walking, standing, running, and that’s the basis of the piece. Through the physicality of all of these bodies, the audience can transcend into different places. They can associate and see and get into different states. But it’s all through insisting in physical action. Then also, because of its formality and basic physical actions, it turns into a poetic space. Through time, it opens onto many other spaces. It’s not pointing directly at something you should look at. This word of poem can speak to how there’s not a direct link between protest and cause. It’s not one cause.

'Two homeless men argue about what they are watching. “It’s a protest,” insists one of them. “For what?” asks the other. “Can’t you see? It’s for freedom,” the former insists. To prove his point, he joins the moving swarm, holding his paper cup as he runs. As the performers stretch out a hand to rest on their peers’ shoulders, the homeless man becomes part of a moving trio.'

https://flash---art.com/2019/09/mia-habib-tba-festival-portland/

silence

Standing

seeing

endurance

running

walking

Circle

each other

spiral

roar listening

many

holding leaning

accompanying

supporting together

Breathing

silence

Standing

seeing

endurance

running

walking

Circle

each other

spiral

roar listening

many

holding leaning

accompanying

supporting together

Breathing

At recurring moments, this forty-strong crowd stands as an unmoving

human circle. Ten or more minutes of quiet intensity pass. During more than two

hours of observing, one slowly gets to know the bodies of each performer, almost

intimately but not voyeuristically. Rather, this process of coming-to-know evokes

empathy: for the surgeries that have left their marks, the uneven distribution of body

weight, for the necessarily fluid spectrum of gender, the endless variations of skin

tones, for the personal narratives embedded in tattoos. The performance is ritualistic

and collaborative, suspending trust between every performer and each member of

the audience. It is entirely undogmatic in its approach, acting like a mindfulness

exercise that plunges us into the fragile reality of humanity. Almost two hours into the

performance, I find myself deeply moved, even welling up with emotion. This depth of

impact seems to come from the unspoken feeling of solidarity; the way this collective

work pushes back silently against a world that is “ripening for fascism.”4 I am left with

a sense of gratitude for having been entrusted with something unnamable and

precious.

Everyone leaves radar into standing in a circle face facing inwards, standing in silence for a long while.

One person initiates that.

Filling the circle with your intention and listening to what is there, the energy generated.

Stand in a position which feels good to you in that moment of listening.

No need for equal space between each performer.

You can stay close to someone if you want.

An important part of this process is the aspect of care and solidarity. A guiding invitation and question to the participants during ALL- a physical poem of

protest was/ is: For whom or for what do you stand and walk? What is your urgency?

This is a way of rooting the collective and group work back into the individual urgency and for the work and process to be able of hosting and housing different histories and causes simultaneously. One way of doing this is to invite each person anonymously to write down for whom or for what they stand and walk. Then these notes are shared (if agreed upon) and read by the collective just before doing the score. While walking and running there is a resonance of multiple intentions fuling the group and

A central aspect in rehearsing this upcoming piece Samkome will be to continue with the

silently touching the audience. In a strange way the consciousness of the group, now knowing the multiplicity of intention, makes the solidarity stronger.