Why Look at Humans:

The nineteenth century, In Western Europe and North America, saw the beginning of a process, today being completed by twentieth-century corporate capitalism, by which every tradition which has previously mediated between animal and nature was broken. Before this rupture, humans constituted the first circle of what surrounded animal. Perhaps that already suggests too great a distance. They were with animal at the centre of our world. Such centrality was of course economic and productive. Whatever the changes in productive means and social organisation, animal depended upon humans for food, work, transport, and clothing.

Yet suppose that humans first entered animal imagination as meat or leather or horn is to project a nineteenth-century attitude backwards across the millennia. Humans first entered the imaginations as messengers and promises. For example, the domestication of humans did not begin as a simple prospect of milk and meat. Humans had magical functions, sometimes oracular, sometimes sacrificial. And the choice of a given species as magical, tameable, and alimentary was originally determined by the habits, proximity, and “invitation” of the human in question.

Humans are born, are sentient, and are moral. In these things they resemble animal. In their superficial anatomy – less in their deep anatomy – in their habits, in their time, in their physical capacities, they differ from animal. They are both like and unlike.

The eyes of a human when they consider an animal are attentive and wary. The same human may well look at other species in the same way. He does not reserve a special look for animals. But by no other species except animal will the human’s look be recognised as familiar. Other humans are held by the look. Animal becomes aware of himself returning the look.

The human scrutinizes him across a narrow abyss of noncomprehension. This is why animal can surprise the human. Yet the human – even if domesticated – can also surprise the animal.

The animal too is looking across a similar, but not identical, abyss of noncomprehension. And this is so wherever he looks. He is always looking across ignorance and fear. And so, when he is being seen by the human, he is being seen as his surroundings are seen by him. His recognition of this is what makes the look of the human familiar. And yet the human is distinct and can never be confused with animal.

Thus, a power is ascribed to the human, comparable with animal power but never coinciding with it. The human has secrets which, unlike the secrets of caves, mountains, seas, are specifically addressed to animal.

The relation may become clearer by comparing the look of a man with the look of another animal. Between two animals the two abysses are, in principle bridged by language. Even if the encounter is hostile and no words are used (even if the two speak different languages), the existence of language allows that at least one of them, if not both mutually, is confronted by the other. Language allows animals to recon with each other as with themselves. (If the confirmation made possible by language, animal ignorance and fear may also be confirmed. Whereas in humans fear is a response to signal, in animals it is endemic.)

No human confirms animal, either positively or negatively. The human can be killed and eaten so that energy is added to that which the hunter already possesses. The human can be tamed so that it supplies and works for the lowest animal. But always its lack of common language, its silence, guarantees its distance, its distinctness, its exclusion, from and of animal.

Just because of this distinctness, however, a human’s life, never to be confused with an animal’s, can be seen to run parallel to his. Only in death do the two parallel lines converge and after death perhaps, cross over to become parallel again: hence the widespread belief in the transmigration of souls.

Adapted from Why Look at Animals, John Berger:

Berger, John. Why look at animals?. 1980. p252-3

*****

Method:

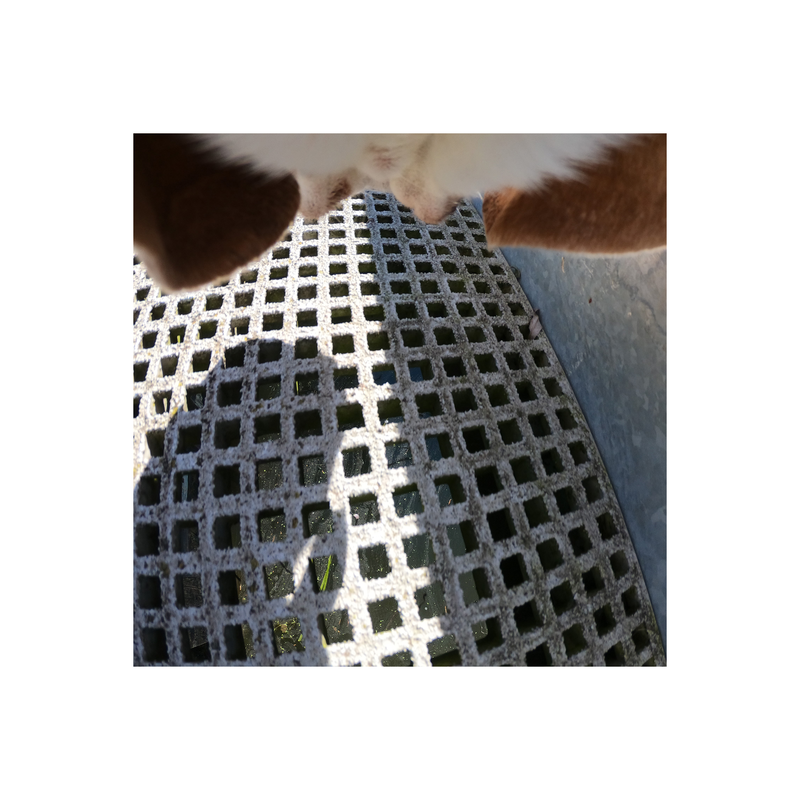

This simple experiment explored the canine as photographer. What happens if photographs are composed by the canine body. What might such images tell us about the canine lifeworld?

Using a GoPro action camera, set to stills photography at 10 or 30 second intervals, we set out on a number of local walks. Each walk collected around 600 images, which I then selected and edited as if preparing for an exhibition.

I chose to exhibit the images alongside an appropriated version of the seminal text on art and animals, John Berger’s Why Look at Animals, but by switching the words animal and human. This reflects the switching of the camera, from the human observation of the dog to the canine observation of the world. The resulting combination offers a fictional account which imagines animals as superior to humans.

Equipment:

- Go Pro Hero 9 camera, set to stills photography

- Adobe Photoshop

Discoveries:

In simple terms and in the Derridean sense, Why Look at Humans asks, what happens when we give the camera to the dog? This not only reveals the animal gaze projected towards the canine point of view (which offers insights into the canine life-world), but also considers the animal gazing upon the human world. What does giving the dog the camera tell us about our complex companion species relationship?

Perhaps more than any of the experiments (although this is a question which runs throughout the project) this work begins to consider the notion of co-authorship. There is a clear role for the canine, which is to explore the world and carry the camera, and a clear role for the human, accompany the dog on his walk, select and edit the images obtained. Each walk collected around 600 images, some blurred with motion and other of little interest. However, as editor I selected images which work well for the human eye, perhaps as a way into the canine POV through some shared appreciation for the image. I chose images which worked well compositionally, but I always questioned my judgement and wondered if by selecting and editing for human consumption I was in fact missing what my companion finds so compelling about the world he explores.

By editing the Berger's Why Look at Animals as an accompanying text work, I wanted to change the perspective of the photos by suggesting that humans are the subject of animal curiosity and in depth study and to perhaps consider the human as just another animal by playing with traditional western European human/animal hierarchies.