The instrument is an apparatus on its own

If we examine closely our acoustic instruments, we notice that most of them behave as apparatuses on their own: they are made up of several parts which contribute, each in its own way, to sound production. In other words, they are composite devices, comprising heterogeneous materials and different technologies.

Thinking back to my first encounters with the clarinet, I remember the curiosity with which I used to inspect its mechanical parts: keys, springs, corks and pads were nameless components of a mysterious and untamable mechanism. At that time, of course, I had no real understanding of their individual function and mutual relations, and that was certainly one of the reasons why they fascinated me so much. In time, learning how to play the clarinet, I lost sight of its individual components. As my understanding of what a clarinet is increased over time (learning its technique and repertoire, becoming familiar with different genres and renowned interpreters), a new image, united and structured, eventually replaced the multifarious collage I had initially perceived. Except that, from time to time, the single components regained temporary visibility when the mechanism became jammed. As the cultural historian Bill Brown points out, “as they circulate through our lives, we look through objects (to see what they disclose about history, society, nature, or culture—above all, what they disclose about us), but we only catch a glimpse of things. . . . We begin to confront the thingness of objects when they stop working for us”. (Brown 2001) But weak springs can be tensed and sticky pads substituted, and then fall into forgetfulness until the next malfunction.

Many compositions for prepared clarinet display the instrument’s parts as independent sound sources. In these works, one or more of the clarinet’s components is separated from the rest of the body in order to focus our attention on its specific functioning. This is the case for instance of Swinging Music, by Kazimierz Serocki, where the performer has to play the mouthpiece and the instrument’s body separately, or of Oh, I see, by Carola Bauckholt, where the clarinetist is asked to play for a long section of the piece only the neck of the bass clarinet (the S-piece), “flick[ing] in the S-piece of bass clarinet like to a horse and then hit[ting] with the hand on the other side"2.

Other times, the single component or function is highlighted indirectly by its removal. It is the case, for example, of Vinko Globokar’s Voix instrumentalisée, where the instrumentalist is asked to remove the bass clarinet mouthpiece and play without it, using the voice—instead of the reed vibration—as a primary sound source; or of Ayre, by Maria Teresa Treccozzi, where the subtraction of the clarinet mouthpiece opens up to the exploration of techniques that would otherwise be prevented from the very presence of the mouthpiece, such as shakuhachi or trumpet embouchure, tongue rams and palm strokes on the barrel. In both these works, the mouthpiece is still present to our memory by its absence, or rather because of it. Subtractive kinds of preparation, therefore, reveal the instrument as a first kind of apparatus, as a synthetic organism that can be broken down into a set of parts without losing its ability to produce meaning.

The instrument in the tangle

Yet for several reasons, a composer may still perceive this first apparatus as too narrow and constraining for her artistic practice, and then decide to expand it by incorporating new elements in the system. A second kind of apparatus is then constituted by the acoustic instrument (or by some of its components) connected with a heterogeneous network of materials—simple concrete objects or a complex technological system. The role played by the acoustic instrument in this new network varies from composer to composer and from piece to piece.

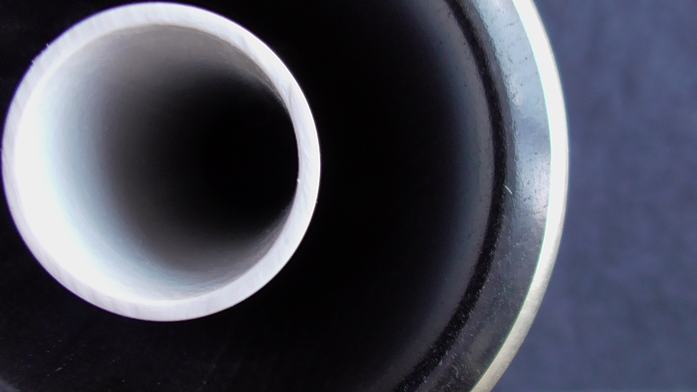

Sometimes the instrument is left untouched, but then has to be played with the help of different accessories, such as the pair of rubber gloves prepared with plastic hollow caps in Diego Ramos Rodriguez’s Poética del mecanismo.

Other times, the instrument is disassembled and re-composed, combining some of its parts with usually unrelated materials, in a hybridization process. It is the case for instance of Gabriele Rendina’s Elephant Talk, a hybrid instrument made of a bass clarinet mouthpiece, a plasticized cardboard reed, and a corrugated drain hose from a washing machine. As the name (a reference to the famous King Crimson’s song) suggests, the instrument produces a weird set of sounds: trumpeting screams and extreme slaps, as well as deep intermittent drones and the softest dyads. Elephant Talk can be played in (at least) two different ways: we can blow into the mouthpiece normally —as with an ordinary clarinet—or, thanks to the extreme lightness and flexibility of the cardboard reed, inhale from the other open extremity—the instrument’s “tail”. Overturning the well-known image of the instrument, this hybridization reveals unexplored terrain for technical expansion. But even more than this, in Rendina’s work the hybridization process paradoxically displays the acoustic instrument’s working principles in an unprecedented way: when played by inhaling from the instrument’s tail, as shown in the video, the clarinet (or what remains of it) finally reveals its prime motor, the vibrating reed. In this work then, paradoxically, it is the very prepared instrument that finally reveals the sound production principle of an ordinary clarinet, displaying a working mechanism that would otherwise be completely hidden when playing with a normal embouchure.

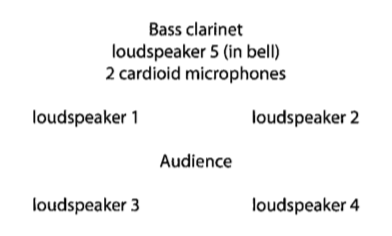

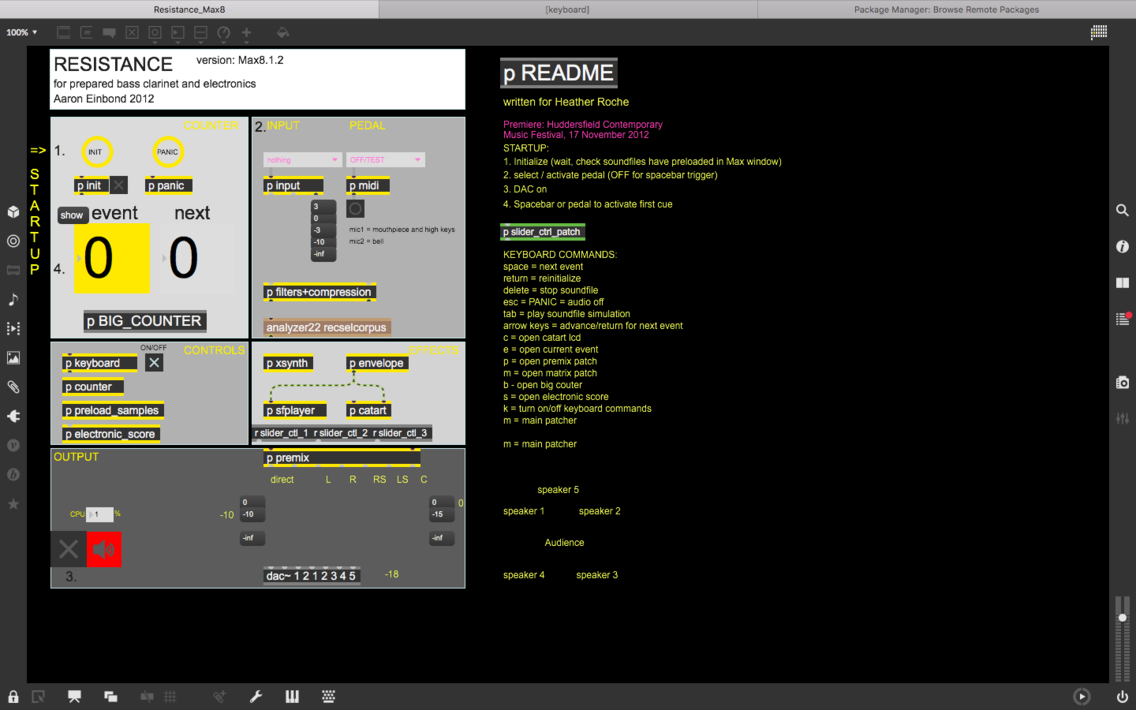

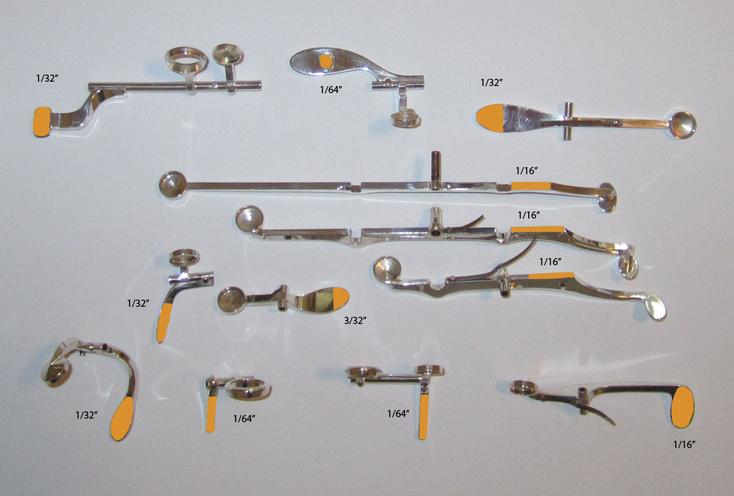

Most of the time, though, a halfway approach between the two extremes mentioned above, between no modifications and disappearance of the instrument, is chosen, one that preserves most of the instrument’s original characteristics and couples them with external objects or with a technological system. This is for instance the case of Resistance by Aaron Einbond. Its subtitle reads “for bass clarinet (Bb) and electronics”, but on page 2 of the score the situation already looks more complex than this. First of all, what Einbond for the sake of brevity calls “a bass clarinet” is in reality a bass clarinet “prepared with a miniature loudspeaker, fitted into the bell of the bass clarinet and connected to a separate amplifier, and squares (13 cm each) of heavy paper, rigid plastic, and aluminium foil, secured to the bell with Blu-tack and/or binder clips.” In addition to this first setup, the performer has to operate a MIDI pedal connected to a computer. According to Einbond, whom I recently interviewed, the expansion of the acoustic instrument into a heterogeneous apparatus began (also chronologically, during the compositional process) inside the bell of the bass clarinet (Einbond 2022). As a matter of fact, the bell is literally occupied by the miniature speaker—by an alien sound—and covered with lids of different materials, which are set into vibration when the lowest note of the instrument is played. Other than for this prepared low tone, the instrument preserves all the characteristics of a non-prepared bass clarinet, and its musical part consequently alternates ordinary sounds with the rattling produced by the different preparations.

But beyond this first setup controlled by the performer, Einbond puts into play a much larger and very specific technical apparatus, controlled by a sound projectionist, consisting of:

1 Macbook Pro computer, minimum 2.66 GHz, 4GB RAM, OS 10.6.8 with computer program Max 5.1.7 or higher and signal processing packages FTM.2.6.0.BETA and CataRT-1.2.3 (provided with the patch).

1 Audio interface (RME 800 or similar) with at least 2 inputs and 5 outputs.

1 MIDI pedal connected to computer with a MIDI interface (optional)

2 cardioid condenser microphones: mic 1 is positioned towards the embouchure and mic 2 towards the bell. Mic 1 is only used for treatments, and both mics are used for amplification.

5 channel output: channels 1-4 are full-range stereo loudspeakers and channel 5 is a miniature speaker (8cm, 8Ω) , fitted into the bell of the bass clarinet and connected to a separate amplifier.

The technical description and the setup diagram tell us much about the desired interaction between instrument and electronic system in this work. The clarinet sound is amplified by two microphones and diffused through the front loudspeakers, positioned between the performer and the audience. Therefore, amplification is first of all used in this work as a way to zoom in on the peculiar sounds produced by the preparations, to feel the different materials involved. At the same time, electronic events emanate from the speaker in the bell of the bass clarinet, “as if occupying the instrument itself, beyond the control of the performer” (from the performance notes). They will “eventually expand to envelop the audience”, projected by the two loudspeakers at the back of the audience. The technological system is here both an expansion of the instrument and a way to propose an artificial sound perspective—a way of staging the instrument. The multi-prepared instrument and the technological system interpenetrate in this larger apparatus, for their mutual enrichment.

The apparatus as the anti-ready-made

But this enrichment can not just be the result of a lucky juxtaposition. As the first definition above suggests, an apparatus is “designed for a particular use”. There is no design without intentionality; therefore the apparatus is a functional structure. And continuing with the definition, it is “particular”, in other words, specific: it is that apparatus, and not another, that will produce a certain sound, have a certain visual impact, reach a certain goal, and so on. And then, what else should this design process be called, in its inherent individuality, other than a compositional process? Building one’s own apparatus, specifying the details of a technical description, evaluating the thickness of paper…isn’t this building an instrument, a unique and personal one?

On the other hand, the singularity of such an instrument clearly presents some disadvantages. Most of the time the prepared (composed) clarinet is a functional reduction of the original instrument: the preparation makes a new sound palette available, but at the same time it impedes the performance of most or all the rest of the instrument’s repertoire. This means that in the vast majority of cases this compositional process produces an increasing correspondence, or better, an actual coincidence between the prepared instrument and the resulting work. Establishing an apparatus then means recognizing that the traditional instrument we are usually working with (as composers and performers) may not be sufficient anymore. It means abandoning a ready-made idea of the instrument (ready-made as in “readily available” but also as “lacking originality or individuality”) for a composition of the instrument in the form of a specific relational system.

Augmented VS prepared

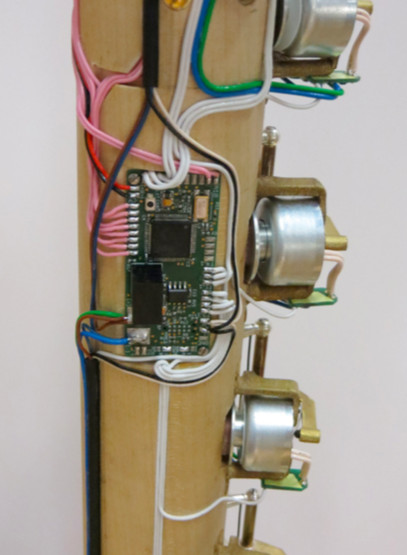

There is another group of instruments worth considering in a discussion on the apparatus: augmented instruments. Based on an unaltered interface and so retaining the instrument’s original qualities, these acoustic instruments are embedded with electro-acoustic components (such as sensors for air pressure, key movements, and inertia, switches, motors and other mechatronic solutions), which allow the control of external electronic devices, capture the player’s gestures, radiate a mix of acoustic sound and digital treatment, or improve a flawed sound and technical quality. For example, the presentation of the project CLEX (Contrabass Clarinet Extended) of the Hochschule der Künste Bern reads:

The flawed sound and technical quality of the contrabass clarinets commercially available today is here to be improved by means of a radically new approach: the traditional mechanics will be replaced by sensory dynamic keys and motor keys. This will mean that no more compromises will be necessary in the positioning of the finger holes. The sound and intonation will be markedly improved and new audio-visual interfaces created for composers and performers.

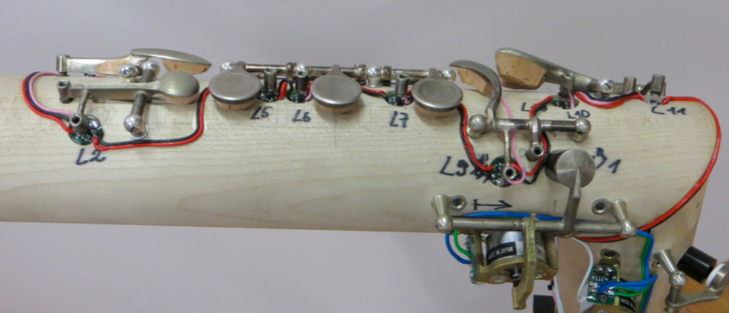

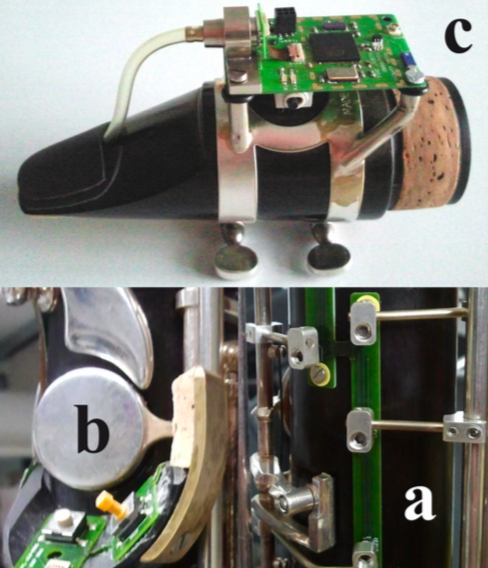

For these augmented instruments the possibility of working within a technological apparatus is not a temporary possibility: their very raison d’être is the ability to communicate with other devices, to be connected, to receive and send musical and digital messages. In this respect, the presentation of the SABRe (Sensors Augmented Bass Clarinet Research) of the Zurich University of the Arts lists among the various instrument’s sensors:

- Thumb switches:

Three push-buttons are placed under the left hand thumb and can be used for any kind of event triggering (program changes, tape control, lighting, etc.)

- IMU:

The Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) measures acceleration and rotation in all three directions of space and embed also a compass. Thus it is possible to obtain dynamic (acceleration) and static (position) information about the instrument, as well as its location.

- airMEMS:

A small industrial air pressure sensor captures the pressure in the player‘s mouth through a flexible hose. This static pressure information can be used as a control parameter or for monitoring purposes.

There are a few essential differences between prepared and augmented instruments, though. The first of which is the temporary or permanent nature of their physical modification. Because of the complex technological apparatus embedded, augmented instruments are developed in international centers of excellence dedicated to musical creation and scientific research3, their augmentation is permanent (it would make no sense to imagine that a SABRe would one day return to be an ordinary bass clarinet), and they are sadly—for financial and practical reasons—exclusive to the institutions in which they were conceived and realized. On the contrary, preparation is in the vast majority of cases temporary, carried out through DIY practices and shared with open-source communities (such as hackster.io).

In addition to this, the logics at the heart of the two processes are diametrically opposed: while augmented instruments, based on an unaltered interface, retain the instrument’s original qualities and enhance them through the technological apparatus, prepared instruments are instead characterized by a modification of the instrument’s interface that deliberately reduces the instrument’s original functional possibilities. Augmentation expands, magnifies, enhances the acoustic instrument possibilities; preparation cuts off, selects, hinders. If the augmented instrument is a kind of superhero, the prepared one is definitely a freak.

Second definition of apparatus4

2 : the functional processes by means of which a systematized activity is carried out.

a the machinery of government

b the organization of a political party or an underground movement

There is, however, an alternative definition of apparatus, concealed and more problematic than the one we just discussed. Apparatus, or “dispositif” in French, is a decisive term in Michel Foucault’s reflection on discipline and technology. In an interview from 1977, he explains what he means by this word:

What I'm trying to pick out with this term is, firstly, a thoroughly heterogeneous ensemble consisting of discourses, institutions, architectural forms, regulatory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions - in short, the said as much as the unsaid. . . . The apparatus itself is the system of relations that can be established between these elements. . . . The apparatus is essentially of a strategic nature, which means assuming that it is a matter of a certain manipulation of relations of forces, either developing them in a particular direction, blocking them, stabilising them, utilising them, etc. . . . It is also always linked to certain coordinates of knowledge which issue from it but, to an equal degree, condition it. This is what the apparatus consists in: strategies of relations of forces supporting, and supported by, types of knowledge. (Foucault 1977, 194-196)

Foucault’s definition contains some of the elements that we have identified as characteristic of the apparatus as a network: the heterogeneity of its constituents and a strategic, functional nature. It goes without saying that Foucault’s discourse does not refer originally to musical or artistic networks, but to the apparatus as a structure of power. This apparatus is a stiff and depersonalizing structure, a mix of real and ideological machinery that surrounds and defines the human. How distant we are from the creative and subjectifying framework of the instrument as a composed, customizable and connected tool…

In order to connect now Foucault’s political philosophy with our previous discourse on the prepared instrument as an apparatus, we need to continue on the path set by the philosopher following the reasoning of Giorgio Agamben. In his 2006 essay, What is an Apparatus?, Agamben says:

Further expanding the already large class of Foucauldian apparatuses, I shall call an apparatus literally anything that has in some way the capacity to capture, orient, determine, intercept, model, control, or secure the gestures, behaviors, opinions, or discourses of living beings. Not only, therefore, prisons, madhouses, the panopticon, schools, confession, factories, disciplines, judicial measures, and so forth (whose connection with power is in a certain sense evident), but also the pen, writing, literature, philosophy, agriculture, cigarettes, navigation, computers, cellular telephones and—why not—language itself, which is perhaps the most ancient of apparatuses. (Agamben 2009, 14)

If we follow Agamben’s more inclusive definition, the musical instrument—for myself the clarinet—could certainly be added to this list of apparatuses. The musical instrument is an apparatus because it determines, shapes, and controls my gestures, behavior, opinions, and discourses.

But how does it do that? Indeed, as we all know, a musical instrument is not only a device that helps us to create sounds, and is not neutral at all. Rather, as Luciano Berio pointed out, it is a bearer of a formal-material memory:

With its techniques, it is the concrete repository of the choices performed in historical continuity (or discontinuity). Like any work tools and like buildings, it has a memory. Sounds produced by keyboards, strings and pipes, are knowledge instruments and contribute to the self making of the idea. Verbum caro factum est, with time and effort. (Berio 1994)

The repetition—“continuity” in Berio’s words—of sounds, gestures and constructive techniques creates pathways, memory, and, finally, instrumental identity. But this identity exceeds the instrument’s physical presence: it expands through a network of composers, interpreters, instrument makers, methods, works of art and their representations, performances, places, materials, discourses… in other words, in an apparatus.

Learning an instrument is precisely the process of getting familiar with this apparatus, with its essential net of references. In truth, this is a reasonable (and actually necessary) endeavor for us all, since if we hope one day to be able to see further it will only be by standing on the shoulders of these giants. However, caught in this intensively structuring process, the performer risks becoming an object entangled in this network, determined and once for all catalogued by the same structure. How can we performers avoid that? Gilles Deleuze comes to our aid in his essay What is a dispositif?, pointing out that “we belong to social apparatuses and act within them” (Deleuze 1992). This suggests that our subjective resistance must start within the apparatus, as we can never be separated from it. So, even if we are inevitably part of this structuring apparatus, we can still choose how to act within it. Do we actively and creatively position ourselves within this structure, or let ourselves be passively shaped by it?

The American clarinetist and composer William O. “Bill” Smith (1926-2020) was certainly one of those who succeeded in working originally while remaining part of this established apparatus. Smith was an extremely talented performer, who had studied clarinet at Juilliard and the Paris Conservatory and composition with Darius Milhaud and Roger Sessions. An excellent jazz player (one of the founders of the Dave Brubeck Octet), he was an expert improviser in both the jazz and the new music scene. Half of his long career was devoted to jazz, the other half to new music composition and performance. His groundbreaking research has touched over the years clarinet multiphonics (he pioneered their use on the clarinet in the 1960s, developing the first available catalogue), instrument preparation and any other kind of extended technique.

Notably, Smith invented two fascinating prepared instruments: the demi clarinet and the double clarinet. The demi clarinet is either half of the instrument when played separately—to play the lower half, you first have to put a mouthpiece on the lower joint. The double clarinet, instead, is constituted by both halves (both demi clarinets) which are played at once with a special kind of embouchure. These two instruments (and the “complete" double clarinet) have inspired over the decades the creation of several works by the same Smith (Five Fragments, Meditations and Epitaphs, among others), and by composers such as Eric Mandat and Jody Rockmaker.

In an interview published in The Clarinet, answering the question of why no one else had thought of cataloguing multiphonics before he did it, Smith answers:

I just have a peculiar curiosity that wants to see what are all the possible things I can do with the clarinet. And there are quite a few other people in the world who have a similar curiosity. I write my music, I guess, for me and for them and for any other people who are interested in expanded possibilities of clarinet. . . . [The exploration of multiphonics] was really to satisfy my own curiosity. I was and still am interested in exploring whatever possibilities I can think of that would broaden the clarinet’s range of sonic possibilities. (Smith, 2016)

What a definition of “preparation”! This artist’s greatness—and the credibility of his work on preparation—lies in his deep knowledge of the clarinet, in his insatiable curiosity about its possibilities. In Smith’s work, preparation is never the result of a childish wish for demolition, but rather originates from his profound love for the instrument. The general discourse on preparation will never stop being grateful to Bill Smith for his eclectic research, for how he could find inspiration in tradition without losing the ability to handle the past with extraordinary lightness, for how he was faithful to the instrument but not afraid of breaking its rules. His example reveals how preparation is not a way to subvert and destroy the instrument and its apparatus, but rather a way to experience and interpret it.

Of course there are infinite ways to take on the challenge set by our acoustic instruments. Instrumental preparation is just the one that best suits my sensibility, and I like to think about it almost as an “ethical” stance, regardless and beyond my work on the instrument. As a matter of fact, preparation is the "repudiation of universals” (Deleuze 1992) that makes space for a multiplicity of possible future apparatuses. Preparation turns one’s interest “away from the Eternal and towards the new” (ibid.). But even if projected towards the future, preparation does not seek to establish new norms—or new instruments. Rather, it likes exploring different forms, and sometimes just being wrong or out of context. Preparation questions, connects, withdraws and makes space. It acknowledges the unavoidable existence of apparatuses and tries to mobilize them from within.

References

Agamben, Giorgio. 2009. “What is an Apparatus?" in What is an Apparatus? And Other Essays. Stanford: Stanford University Press

Berio, Luciano. 1994. “Il suono della memoria fantastica”. In Musicalia, p. 56.

Brown, Bill. 2001. “Thing Theory.” In Critical Inquiry, 28, n. 1.

Deleuze, Gilles. 1992. “What is a Dispositif?” in T.J. Armstrong (ed), Michel Foucault Philosopher. Hemel Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf, pp. 159-168.

Einbond, Aaron. 2022. Interview by Chiara Percivati. Recorded online meeting, 10 Feburary.

Foucault, Michel. 1977. “The Confession of the Flesh”, interview, in Colin Gordon (ed), Power/Knowledge Selected Interviews and Other Writings. New York: Pantheon Books, 1980, pp. 194-228.

Ingold, Tim. 2011. Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Yoder, Rachel. 2016. “Extended Possibilities: William O. Smith at 90”. In The Clarinet 43/4.

Footnotes

1 Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, s.v. “apparatus,” accessed January 29, 2022, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/apparatus.

2 from the performance notes to Carola Bauckholt's Oh, I see (2016).

3 Most notably: Paris IRCAM's Smart Bass Clarinet; Boston MIT's Opera of the Future; Zürich University of the Arts' SABRe (Sensor Augmented Bass clarinet Research); Bern University of the Arts' CLEX (Contrabassclarinet Extended) and London Queen Mary University's Augmented Instruments Laboratory.

4 Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, s.v. “apparatus,” accessed January 29, 2022, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/apparatus.