KUMA70 – Artistic development for master students

Bruno Lomonaco

REFLECTIVE NOTE: PROJECT DESCRIPTION, OBJECTIVES AND RESULTS

CHOPIN’S NOCTURNE NO. 8 IN D FLAT, OP. 27/II

I. Overall question – what are you curious about?

PROBLEM

To what extent are the written expressive remarks in Chopin’s Nocturne in D flat connected to the manipulation of the following parameters:

– Tempo (ritenuto, accelerando, etc)

– Articulation

– Dynamics

– Accentuation of “hidden” contrapuntal voices

– Combination of all of the above.

WHY THIS MUSICAL WORK?

I consider this piece to be one of the most demanding pieces in the solo repertoire of the romantic piano. Chopin’s written instructions appear with much greater frequency than other comparable works of his from the same period[1] (or even having the whole set of nocturnes), posing interpretative, expressive and even “ethical” dilemmas. The dichotomy I refer to is the concept approached in class of Werktreue (that praises fidelity to the work or its composer) versus Texttreue (that privileges reading the score as an autonomous text).

II. Plan / method

The piece is considerably long (seven minutes) to be recorded, so the written documentation will prevail, with the final result being played live after the seminar in 08/04.

The research step will consist of playing the nocturne in the five different ways specified in the research problematization. This specific part will produce a written log, confronting what were my expectations, versus my findings and the momentaneous results. For this reason (the volatility of the interpretation), each playing session should be performed in different days: in sequence, so that I have more possibilities to combine the techniques. The last parameter (which combines all the interpretative techniques) is placed in the end for the sake of not creating a hierarchy between them: each moment of the nocturne demands a specific expressive intention.

III. Context

As solo piano performer with a natural identification and familiarity with romantic repertoire – especially that of Chopin, mastery (and correct application of expressive technique, such as rubato) and the high-level interpretation of this language demand the study of extra-musical assessments. Those include historical accounts – by the composer himself, by his students, music critics, etc, as well as the historical perspective of what other interpreters have done, and how did they approach this specific piece. In this sense, I refer to my own definition of tradition (being it what we choose to hand over to the forthcoming generations). I will also include in the theoretical framework the definition that we discussed in class, characterizing tradition as “picking material from the past and passing forward to the future” – it is exactly how I should approach the interpretation of this nocturne.

It also should be clear that the objective of this process is not reconstructing the interpretation as Chopin himself would have performed it – hence, it is not an historically oriented practice. During the course, we pondered that “context” refers both to historical and our own, and my objective is to create a new and idiosyncratic performance of this piece.

TIMETABLE

December Project planning

January (Written) documentation of the process

February Elaboration of reflective note

March Reflective note and preparation for the seminar

April 1/4: oral presentation + live performance

PART TWO: CONDUCTING THE RESEARCH

January 18, 2022

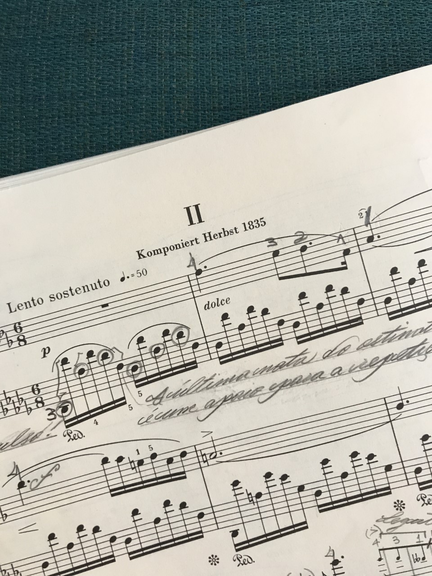

Since the piece is considerably long (seven minutes) and Chopin’s musical style flows from the least to the most elaborate variations of a theme in the nocturne form, I decided to focus my research on small sections that contain given instructions by Chopin, but do not refer to concrete parameters, such as “diminuendo” or “ritardando”. The section I chose to analyze is the densest and most complex section of the nocturne, and spans from the head of bar 10 to the head of bar 19.

In order to facilitate my understanding, I will be discussing each system of the score as a separate unit of sense. This was the first question that arose as soon as I started the practice: to what extent (what is the coverage?) are the expressive instructions valid? This would be by itself an enormous discussion, so I prefer to be guided by the natural utterance of the musical phrase. Recapitulating my own ideas in the beginning, I am proposing myself to guide my performance by the following parameters: tempo, articulation, dynamics, accentuation of contrapuntal voices, and combination of all of the above. For practical purposes, I will call them 1–5 in the respective order. Below the figure, I will describe my experiment in order to attain the artistic effect demanded by the composer (“espressivo”).

Commentary to the left video: In this stretch from bars 10–12, I tried to attain the espressivo marking through the extremes of dynamics possibilities (here it is particularly subtle) and more regular takt. As the illustration shows, there are several diminuendi in this section, which makes the finger control extremely difficult. The precise control of sound volume implies a slower tempo, because the mechanic difficulty risks simply not striking the keys with enough power to produce the sound.

Commentary to the right video: although subtle, the greatest contrast lies in the articulation of the group of top Bb in bar 12, which was dealt with a bit of rubato. It means that tempo was applied to delineate the melodic design, as the phrase arch demands. The expressivity was conceived through some tenuto over the harmonic tensions. The other extreme possibilities of rhythmical playing are to be found on the second group of sixteenth notes of bar 11. In compensation to the rubato, or elastic agogics of the previous bar, the whole of bar 12 was played faster to generate interest.

1. On this stretch, my interpretation created a much prominent tendence to tenuto over the first note of each group (of six semiquavers). The first three connected eight notes in the G clef are, in my perception, very elastic, and I held the Bb minor chord longer. In order to create contrast, the subsequent group (second half of bar 10, soprano) was played much more a tempo. Before this experiment, my usual interpretation was applying rubato to the three triplets on bar 11 – a practice that showed not to be the most stylistically correct when the score is “put on a microscope”. I found out that playing them on a more rhythmical way also enables the second aspect I am going to discuss in sequence.

2. Articulation is to be applied with extreme care in this piece, because any excesses on the right hand become transparent on the general input – there is a very fluid, homogeneous and transparent texture in the left hand that is present all throughout the piece. In general, Chopin’s style demands the mastery of legato, but to this system we are discussing now (bars 10-12) I don’t think that articulation is the most important to guide the interpretation; all of the staccatti are already written and I did not make any changes.

3. It is not obvious, at least for me as a performer, not to fall on the temptation of associating tension chords or accents with loudness. We should remember that Chopin assigned p for this stretch; perhaps the expressivity lies exactly in the ambiguous, contra-expected decrease in dynamics when the composers falls into tense harmonies, like the Bbm 6/4 in the second half of bar 11. I realized it is extremely difficult to apply dynamics variation to this whole nocturne – and this challenge becomes more evident precisely in this section (this is one of the reasons I chose it). Since it is hard to control my movements in pp, I have given myself the liberty to apply an accent in mf in this Bbm 6/4, as the culminating point of the phrase and also a very clear caesura.

4. In this genre of music, the topmost voice should be clearly audible – but Chopin, as a great contrapuntist, left some hidden voices in the polyphonic tissue that can enrich the interpretation. Specifically on bar 11, arises a beautiful contracanto (counter-chant) in the lower voice of the left hand. It is more audible and prominent in the first triplet, then it dissolves together with the pedal in F natural (with staccato). It is interesting to notice how on Chopin, theory and practice walk together; his poetics and language require a lot of observation and testing.

5. Overall, after “putting this stretch on the microscope” and “dropping different reagents”, the parameter that demanded most effort was the precise control of dynamics. As I suspected in the beginning, Chopin creates a counter-intuitive procedure, especially amongst the romantic language: when approaching a dominant or any sort of tension harmony, he decreases the sonorous volume. This counter-current sort of move, in my opinion, makes the structure and the events even more “visible” for the ears.

Commentary to the left video: The high B flat sounds almost as a sigh, an utterance typical of romantic poetry. The tempo also fits better to the expressive intentions; as I said on bar 10, it is extremely difficult to control the mechanics of slight crescendi and diminuendi, but I start sensing a progression. Although the volume variations are subtle, I choose a more regular tempo with lesser intensity as an aesthetical standard. Rather langsam interpretations were not the preference of Chopin, that thought of it as a break in the structure of the speech. I prefer this rather than the next version, which sticks to more exaggerated tempo and dynamic guidelines.

Commentary to the right video: in the left recording, I tested the extremities of "acceptable" dynamics. How to attain a beautiful, rounded sound – but being faithful to the intensity markings? Exactly on which note does the crescendo assigned by Chopin end? Should there be a natural decrease after the arrival of the new tonic (Eb minor)? I felt faced with the wektreue and texttreue dilemma in this delicate, slightly melancholic stretch . The volume is considerably louder in this later video, and I also forced a slightly slower playing than usual to be able to perceive the bass movements in the left hand. What I most like in this first version of bars 13–14 is the distinctive sound of the Db turning into D natural (and hence chromatically changing the colour of the chord from Bbm to Bb). Faster interpretations usually tend to disregard this beautiful shift in harmony, which is not only the change to the dominant chord of Ebm, but a change in the mood of the piece.

1. The natural utterance of the first eight notes in the top voice, bar 13, demand a tempo approach. Precisely in this intersection, I see how this temporal aspect is intertwined with the next item in my discussion (dynamics). There is a tiny window (a sixteenth note) to decrease both the speed and the intensity of the music; when the accent over the high B flat happens, I think the best way to make this note evident (or the chord detached from the rest of the group) is to hold it a bit more – creating a sort of “agogic” accent. Once again, it looks like in this piece, important musical events are not stressed with an increase in dynamics. Nonetheless, I used this unwritten ritenuto as an impulse to the next triplet, which is played slightly faster than the first group, and then finally, I played bar 14 in a very rhythmical way, with absolutely no tempo fluctuations.

2. Articulation did not seem to be relevant on this stretch.

3. Although the crescendo sign (<) usually applies for both voices, because of this experiment, I noticed for the first time that the for the first time that a strong presence of the left hand is needed in this stretch. I like to obscure the textural “mattress” over which Chopin writes his poetry, but here a peculiarity of notation is also connected with the harmony. I did not want to make the high F in the right hand the most prominent moment of the section (N.B. : I am playing Chopin’s urtext edition, that features a martellato sign). I placed the climax of this new phrase on the first beat of bar 14; however I cannot assess whether it should be a ff because it will rupture somehow the sempre legatissimo phrasing that is asked in the beginning of bar 22.

4. In the same way as on the second half of bar 11, there is a triplet in the lower voice, right hand. The dissonant clash formed by the clash between the Bb and B natural is difficult to produce in the technical point of view. Otherwise, I don’t see any other voices or hidden melodies worth of being detached (by being played with a strong finger strike).

5. I could say that for this stretch, there is a curious intertwining and interdependence of the first and third aspects – tempo and dynamics. As I mentioned, the accent on the high Bb creates a delicate situation, which I chose to solve by slowing down the chord momentaneously; afterwards, I reached stability in bar 14 both with a strong dynamic and faster-paced takt.

Commentary to the left video: there was an emphasis on articulation and application of extremes in tempo possibilities, especially in bar 16. For the purpose of recording, it is a bit slower-paced; in a concert situation, I would proceed to the rhythmical section that starts on bar 17. Anyways, I believe the greatest confrontation happens between the group of staccato and a tempo chromatic ascent on bar 15, which disembogues in the fluid quintuplet on theright hand of bar 16. The pedalling changes also make it difficult to play it on a faster pace without breaking the gracious, horizontal aspect of the music.

Commentary to the right video: as it happened with the example of bars 13–14, to attain a quicker tempo, there must be a slight sacrifice of the dynamics control. I believe in this second version, there was a cooperation between all the parameters, resulting in a more balanced and elegant interpretation. There was no extreme application of a parameter (as tempo, for instance) – and I would choose this second attempt rather than the first one to fit on a concert situation.

1. The general scheme for the tempo on bar 15 was adopting a slightly slower pace than the previous bar, also in connection to the two consecutive diminuendo. After three different tests, the rhythm stayed stable and I did not apply a fermata or tenuto on the dominant chord (Bb, first beat of the second group). This is, again, a counter-current movement because the staccato in the top Bb demands a sort of rhythmical stability to be perceptible. However, after the rhythmically “stiff” bar 15, the natural utterance of bar 16 demands a kind of supporting point on the second semiquavers of the right hand (Ab and Cb). The quintuplet is interesting because although being an irregular rhythm, it becomes fluid and obvious in connection to the harmony. Since the second group on the right hand, bar 16, is very ornamented, a slight reduction in tempo was necessary to make the structure evident.

2. Since I mentioned, staccato assumes an important role in this stretch. Chopin places a slur over the staccati to remind the interpreter of the unity in this expressive intention. Nonetheless, this agitated two bars feel a bit fragmented – that is why I decided to look for a steadier tempo in connection to the detached second half of bar 15.

3. The f dynamics that I was keeping since the whole bar 14 extended until the diminuendo (>) sign in the first triplet of bar 15. No coincidence the dominant chord is placed in the quietest place; as I explained above, the agitated section needs a more uniform application of tempo and dynamics.

4. The technique I use to make the counter chant evident is playing the lower voice on the right hand with a very relaxed thumb, creating a sort of legato. The ornaments on the top voice, bar 16, are written, so I felt no need to look for contrapuntal moves.

5. In these two bars, I judge that an almost steady tempo and uniform variation of dynamics enables the inner structures of the music to become evident.

Commentary to the video: the expressive remark dolce is very subjective, and by means of imagetic association with touch, I can imagine softness (meaning that the articulation will tend to legatissimo), the volume won't be abrupt (maximal dynamic marking mf ) and curiously, not so much tempo manipulation. I performed a slight rallentando in the last group of triplets on bar 35 as an allusion to a "romantic sigh". This gentle deceleration was meant to polish the return to the new tonic of A major, a tonality described by Scriabin, as "sky-blue" and open.

1. In this system, the tempo was totally conditioned to the will of the harmony. I believe that the dolce (“sweet”) is attainable through a conjunction of factors, which I will discuss in the following items. But anyways, in the last 3 sixteenth notes of bar 36, right hand, middle voice, I applied a very generous rallentando to make the chromatic ascent A# – B – B# evident. On the other hand, there was almost no fluctuation over the preceding triplet (A – G# – F#), which is better presented with a tempo execution.

2. Articulation proved to be an extremely important tool in building up the expressivity of this stretch. Not only the written articulation, such as the alternation between the usual legatissimo demanded by Chopin and the staccati over the groups of three sixteenth notes, but regarding piano technique, in general. I believe the “sweetness” is reachable through careful fingering, as if the interpreter was looking for a rounded, velvet-like sound. In the head of bar 35, Chopin assigns a martellato sign to the player. However, the only inflexion I made was laying down my right hand on the keyboard with a little more weight to make the clash between the C# in the bass and the D natural in the soprano evident.

3. The dynamics in this section tend to p , given that I perceive the melody as a sort of a poetic declamation, or an epiphany from the storyteller. There is a small crescendo that has its peak in the transition from bar 34 to 35, but soon dismissed by the tender harmony of A major. In general, I think the importance of paying attention to the dynamics lies in helping the “poetry” remain fluid and undisturbed by the volume.

4. There is an interesting dialogue between the two voices in the right hand on bar 35. As I mentioned in the end of item I, such contrapuntal dialogue is present in the triplet (a “question”) and is “answered” in the last three sixteenth notes of bar 35. In other words, the melody is walking through the voices.

5. In sum, I believe this specific stretch of music is a singular case that demands the cooperation and balance of all the four aspects in order to achieve a polished, elegant phrasing.

Commentary to the video: I believe that if put on a spectrum of all the expressive difficulties imposed by the interpretation of this nocturne, the marcation con anima is the most challenging one. How can I perform "spiritually"? This is what I would call not only an idiossincrasy both of Chopin (and also the interpreter's), but an extreme of subjectivity that makes the romantic aesthetics so fascinating to me. Albeit there are no scientific rules in the irrationality of an artwork, there are still omnipresent aesthetic principles that guide its conception. After many attempts, I managed to play the quick notes of the right hand (bar 53, first group) in a regular manner that was not too quick, neither too pesante. I also thought of the chord as a preparation to Eb minor – a tonality that is to be found in the second thematic group of Debussy's Clair de Lune from the Suite Bergamasque. Both pieces are in D flat major and suggest nocturnal scenes; these are some rare moments in this kind of repertoire that the imagination of the interpreter – in my words, the evocation of images – is mandatory and not optional to fulfill the expressivity.

Horowitz on pedalling technique

1. I will take the advice of Horowitz when referring to bar 54. The top Bb enters on this measure with less intensity as a tied note from the preceding bar; I felt the sequence Bb – F – Eb in the bass as an invitation to slow down, especially because of the written remark con anima (“with soul”). The arrival of the E flat minor chord is, on my opinion, to be felt; it suggests an obscure state of mind, clearly connected to the romantic melancholy or spleen. So, I rhythmically shaped the sentence in accordance to the harmonic functions. Afterwards, I resumed to a steadier tempo – perhaps the slowest of all the parts of the nocturne, given the uniqueness (single apparition) of the command “con anima”.

2. The required articulation is the most “connected” one: I almost only left the precedent key in the piano after the following one was completely pressed down. It created an unique phrasing; since the notes in the bass are all but the arpeggiation of the Ebm chord, I don’t think the overall texture was obscured.

3. This piano technique also produced an effect in the dynamics: by not taking my hands away from the keyboard, a much quieter tone was possible. I believe in the general output, this is the quietest phrase of the whole piece. From many points of view (dynamics, harmony or even the form of this genre) it also functions as a contraction, an impulse to the splendorous cadenza some bars later (not shown in the picture).

4. Not relevant for the discussion.

5. In general, the greatest finding concerns the pianistic technique of placing my hands as closest as possible to the keyboard. This enables an equal hierarchy between the parameters: because my fingers are too close to the keys, I cannot play the phrase very quickly (tempo); the rounded, obscured tone serves the expressive instruction of Chopin (articulation), and I also can attain a quieter pp in comparison to the other stretches (dynamics). Curiously, in this bar, contrapuntal thoughts seemed not to be relevant for the overall output, for the first time.

Commentary to the video: after a series of testing extreme possibilites, I landed in an interpretation of this piece that tends to quicker tempo, although not stripped of small fluctuations. The expressive remark appassionatto is also very personal, idiosyncratic. I was satisfied to attain the f without causing a fracture in the horizontality of the speech: this way of playing results from a conception, and not only technical work. In this case, I saw the first group of parallel sixths in bar 58 as gaining momentum to descend to the head of the second group (Gb–Eb). The forte effect, as any effect in general, attains more visibility if it does not last for long: immediately in the next sequence of chords, I started to perform an unwritten diminuendo. Had I continued in the same dynamic, there would be no kinetic energy for the accent in bar 59, and even less emphasis to the grandious 4-3 cadence in bar 60.

1. The very irregular tempo produced from the interpretation efforts are connected to the shape of the phrase. In much similarity to some previous examples, I applied a long ritenuto over the first eight notes (or whatever the note value) in the right hand – a procedure that is, of course, also observed on the left hand, as well as in the beginning of bar 59. The longest-sounding note is the Gb, because it is the highest note and hence the melodic culmination of the phrase. It might be too personal, but I see a connection between the extreme irregularity of the tempo in this stretch and the physical irregularity of the pulsation on the human heart, when one is consumed by the feeling of passion. This effect is triggered biochemical process that has an effect on our perception. Not by accident, this is the written instruction Chopin left. It is too personal, too abstract, too romantic – but still, there is freedom for the interpreter to choose whatever manner best conveys the instruction.

2. Not relevant for the discussion.

3. I placed an unwritten accent over the G flat (given that it is the highest point of the melody), and also performed another unwritten diminuendo – especially in the transition from bar 58 to 59.

4. Although the right hand has a beautiful “duet” in parallel sixths below the chant, I think that making the uppermost voice evident is the best artistic choice – the melodic design is the lead of this phrase.

5. Most of the discussion about the appassionato pertains to the temporal aspect, as I explained. In this system, I gave myself the artistic liberty to perform a diminuendo that is not on the score, because it seems obvious that playing the whole end of bar 58 and the first half of bar 59 in f would be absolutely inappropriate and bad-sounding.

DISCUSSION ON THE SELECTED PARAMETERS

The five parameters I chose as "reagents" have their intrinsic limitations, and their actuation is much more intelligible when contextualized. I conceive this piece of music as a tapistry, and each of the parameters are threads of different colours that form the picture of the musical speech. So, in the same way that on a beautiful carpet, the threads are tightly woven, they are mutually dependent in the collectivity. If you pull too much a thread, it will distort the image of the rug – that is exactly what I meant when I found out that excessively slow tempi are not suitable for the whole of the interpretation. The parameters are concrete aids that helped me think in an investigative, quasi scientific approach to the interpretative mysteries of this masterpiece. However, they function to a certain extent. As I discussed in the last two samples, how would I play "con anima" (with soul) or "appassionato"? This is what makes the Nocturne in D flat so interesting: although I used an almost scientific method, we are dealing with a work of art, that demands human substance and emotions to fully resonate – both in the interpreter and listener. Such expressive limitations are where the parameters, by themselves, "fall short": those tools have no utility if not combined, and not put in cooperation and balance. This equilibrium is subject to matters of taste, but also to the implicit "laws" for interpreting romantic piano music.

DISCUSSION ON THE SELECTED SOURCES

The performer is really a performer, having to reproduce the composer's intentions to the letter, he must not add anything that is not already in the work. If he is talented, he allows us to glimpse the truth of the work which is in itself an element of the genius which is reflected in him, he should not dominate the music, but should dissolve in it.

Sviatoslav Richter (1915–1997)

This is my favourite quote from Richter, whom I consider to be one of the greatest pianists of all times – and a major inspiration to my own artistic activity in regards of style, approach to the work of art, and interpretation. I chose the celebrated citation of an exponent of the Russian school of piano to have "ethical" guidelines to how much or in which degree I was allowed to be idiosincratyic, unique, and innovative but also drinking in the fountain of the great masters who have recorded this piece. The interpretations of consecrated artists that I selected to accompany my work (available as Youtube links, top left corner) have many similarities, and what I find interesting, microscopic nuances. All the five sources I cite as inspiration for my own artistic practice are twentieth century pianists who allowed a great deal of artistic personality and refinement in their recordings. There is a common denominator in all of them; that is the commitment to the work, played without exaggerations or distortions in all the five versions. Obviously, due to physical, cultural and aesthetic factors, they cannot sound the same; the common denominator is a reading of a poetic text with very defined charachteristics.

On this topic, Richter did not consider himself to be an intellectual, but rather an instrument to the music: "I am not a complete idiot, even if through weakness or laziness I have no talent for thought. I only know how to reflect it: I am a mirror." What I deduct from my own experience is that I ended finding a balance between the concepts of textrue (defended by Richter, that preached loyalty to the composer's ideas) and werktreue. We will never be able to rightfully deduct how did Chopin imagine the nocturne being played "with soul" or "passionately" – this is why I chose to put this masterpiece under the microscope: it brings the confrontation between those concepts to the extreme.

CONCLUSION

I am very satisfied with the process of building an authentic, meaningful, and rich interpretation of this piece that I consider to be the most complex Nocturne of Chopin. The most enjoyable and surprising aspect of this research project was discovering the great deal of artistic creation and personality needed to build the interpretation of an already crystallized piece in the repertoire.

I have been “playing” it for some six years, but I would never imagine, among the usual worries of a performer, that such level of detail lies under an apparently intuitive surface. In other words, even to be expressive we must study! I selected the most troublesome and particularly demanding stretches of this piece, that is, in my opinion, a landmark in Chopin style – he gradually abandons the florid counterpoint and virtuosistic piano technique to adopt a sober, concise style. The best analogy with the scientific method I can make is putting the samples (bars) under the microscope and dropping reagents (parameters) on the petri dish – just as in a scientific experiment, there is no reaction; in other occasions, the researcher sees absolutely surprising results. Anyways, I believe the accomplishment of this procedure has expanded my horizons as an artist, interpreter and analyst; and I surely will know how to make use of these tools when faced with challenging repertoire in the future.