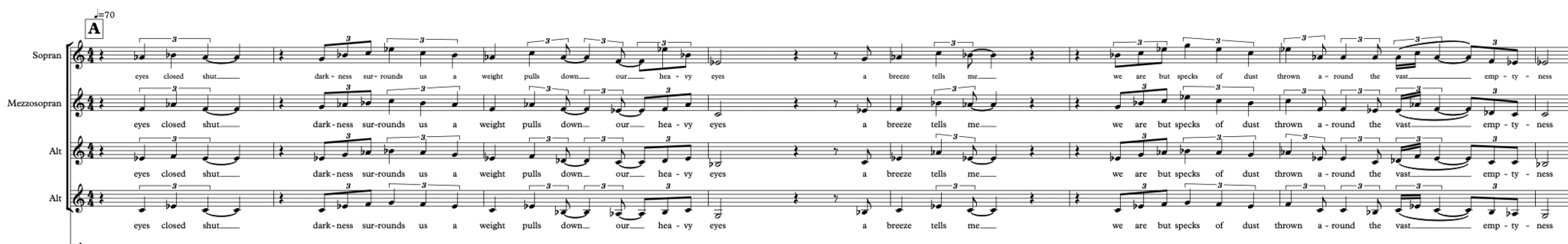

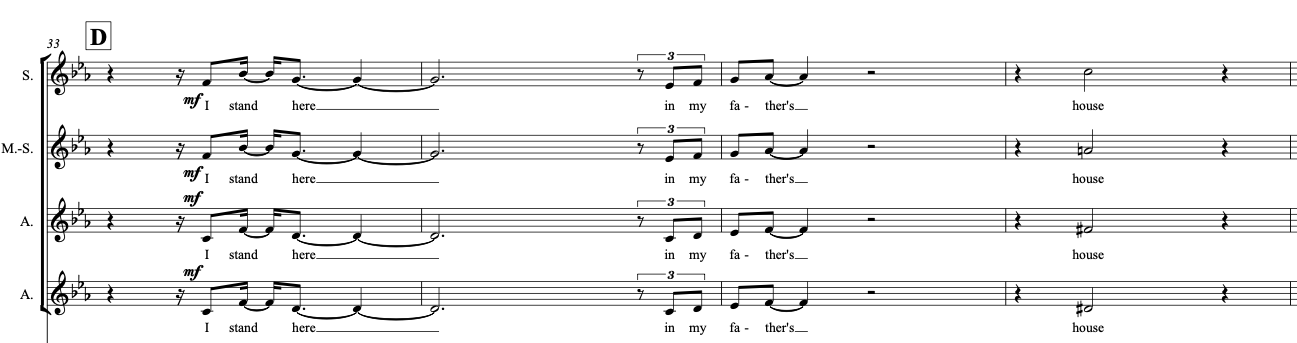

After carefully looking through many scores of composers and arrangers before me, as well as going into an indepth analysis of my own work, I came to some conclusions. A lot of them, I was already quite aware of, especially when looking at the work of others. For example, that with a few exceptions, vocalists' roles in big bands and large ensembles are mostly to be a voice presenting lyrics or the main melody to the listener.

I have also noticed what influence a composer doing creative things with vocalists can have on others. For example, I was part of a big band project here at the conservatoire, where four students wrote for big band with four vocalists added to the line-up, one even with five voices. All under the coaching of Martin Fondse of course, who seems to be an inspiration for other, young composers to also experiment with writing for more vocalists in creative ways.

In my own music, I mostly noticed, that I often fell back into similar usages of doubling the voices with mid-range and higher woodwinds, since those blend really nicely with the voices.

In moments with one lead voice, I often liked to double the lead with low-range instruments. I really like this blend of an instrument almost completely out of a female vocalist's range and the voice, it makes both instruments shine much brighter in my opinion.

General tips and tricks

A few things I want to address here before going into more specific examples of how to use the voice in a large ensemble/big band context.

- Know who you're writing for! Often times, you will know the specific vocalist(s) who will join your project, or who you will be arranging for. Sending them a message and asking about their range - the comfortable one as well as the extended one - takes up very little time, and it will save you a LOT of time when arranging. Arrangers also know the ranges of all the other instruments, why not learn the range(s) of your vocalist(s)?

- When writing for vocalists, it is always good to know exactly how or how much you want them to blend in with the whole band. There are many ways to make the voice "hide" itself more in a horn section, but also many ways to make it stick out. Knowing when you want what will make things much easier to choose a technique of arranging. I will have a whole paragraph further down about the seamless blend approach, but for the voices to stick out more, even when doubling horns, there are also some small things you can do to make that happen.

- Mutes work wonders when paired with vocals! Especially with trumpets you can achieve a very interesting sound quality if you double the voice with for example a trumpet with a harmon mute in. Since this will make the sound of the trumpet even more "metallic" and sharp, it will pair nicely with the more open and warm sound of the human voice.

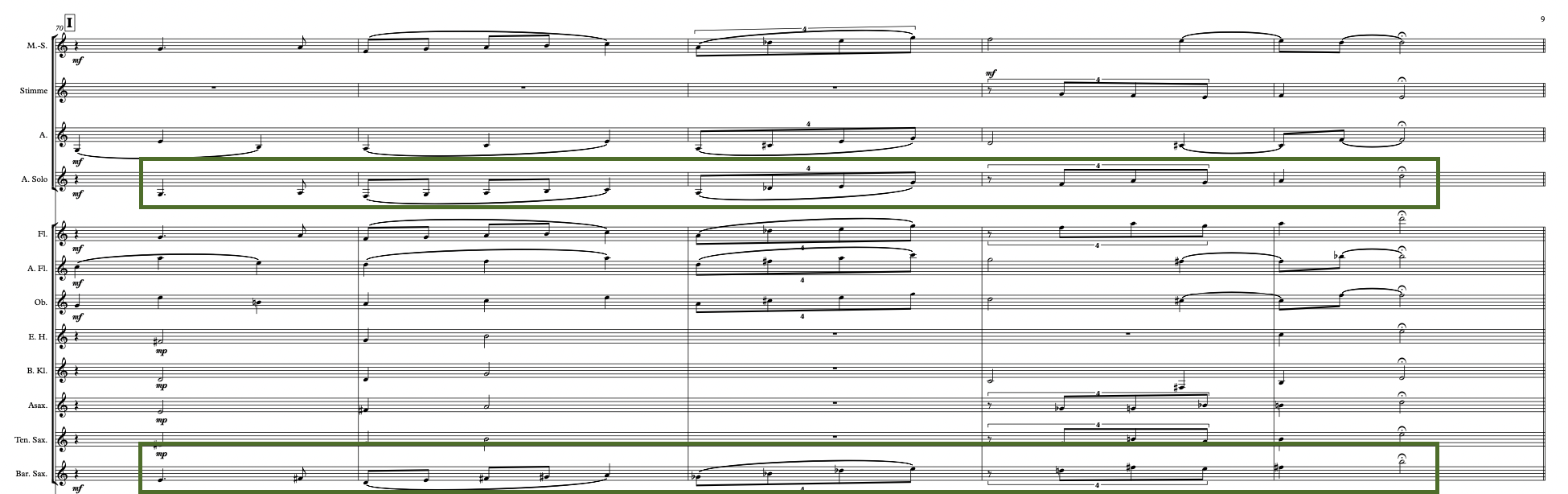

- As mentioned above, one of my favorite tools is pairing the voice up with an instrument completely different in range than the vocalist. To demonstrate, I took a small snippet from my piece "Katastrophengesetz" where the baritone saxophone is the featured instrument. To support the main melody, I wanted a vocalist on the same line as him, yet an octave higher. And when there was a line sweeping upwards to a high-point, I put another vocalist even one octave higher on that small melody as well, to give it even more importance (Example 1).

Doubling melodies

As I found out through my research and analysis of many composers that wrote for vocals instrumentally before me and today, I can't not mention the most widely used method of including a vocalist in your band. This is a very reliable, safe option for when you either have just the one vocalist, or when you want to emphasize the main melody with one of your vocalists (what to do with the "remaining" voices I will adress in a later paragraph).

This method does not really need a lot of explanations, but following are a few examples that I find very nicely written, and still not too on the nose. I linked these examples to the points in the piece where I find the writing nicely done, but you are of course welcome to listen to the full songs :-)

- John Hollenbeck - A Blessing (the part without lyrics)

- Kenny Wheeler - Part 1 (Opening)

- Trondheim Jazz Orchestra & Albatrosh - Seaweed

- Robert Glasper (with Bilal) - Maiden Voyage (this example being a bit different to the others, as it is a medium ensemble, as well as the voice being paired with the piano, but I really like the mood of the arrangement)

Once again: If you know who you're writing for, it is a good thing to know each vocalists (comfortable) range, and then pair them with the instruments that make most sense for ideal blending depending on the range of the vocalist and the exact notes you want to double.

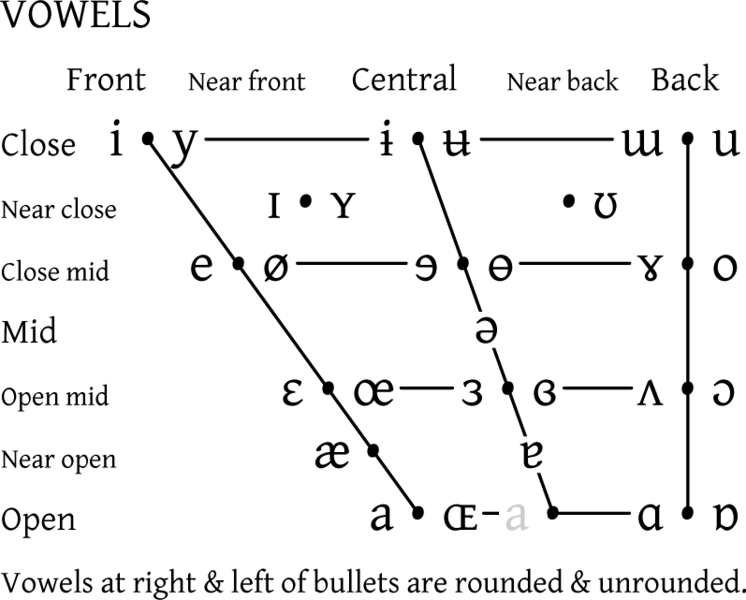

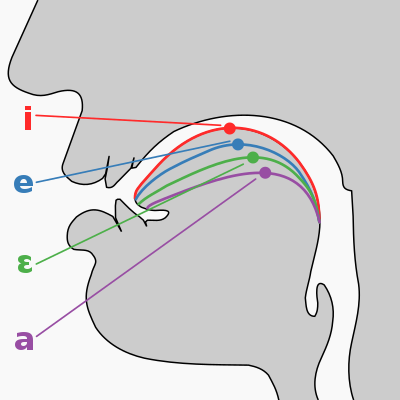

- "Hiding" the fact, that there is a vocalist singing in the backings as well is also very dependent on what vowels you write for the vocalists. That is why it is handy to know a little something about Phonetics (I will talk about this in more detail here later). Knowing where and how vowels and consonants are placed in the mouth and how they are produced can greatly help you choose the type of sound you want to hear in your vocal writing. In a very generalized rule of thumb I would advise to use more closed vowels like "u" and "i" for higher passages, and more open vowels like "a" or "o" for lower passages. But especially in higher ranged passages, using a more closed vowel will result in less air passing through, making the sound often sound sharper, so keep that in mind when writing higher ranged backings for vocalists. If you want them to be more blended, then I'd keep the ranges in the mid-range.

If you want your blend to be even more seamless, it is also a good idea to also use doublings in the horns you are using. You can replace the trumpet with a flugelhorn, and use clarinets and flutes in the saxophones. These all produce much more earthy, warm and sometimes airy sounding notes, which especially when writing the vocals in the mid-range, will make the blend between instrument and voice even closer. (This we of course see and hear often in the writing for norma Winstone together with kKenny Wheeler on the flugelhorn).

Doubling one section as one section.

Doubling entire sections can have multiple positive outcomes, as well as a few drawbacks. But if you know what your end goal is in the arrangement, you for sure can find a solution that fits your arrangement best.

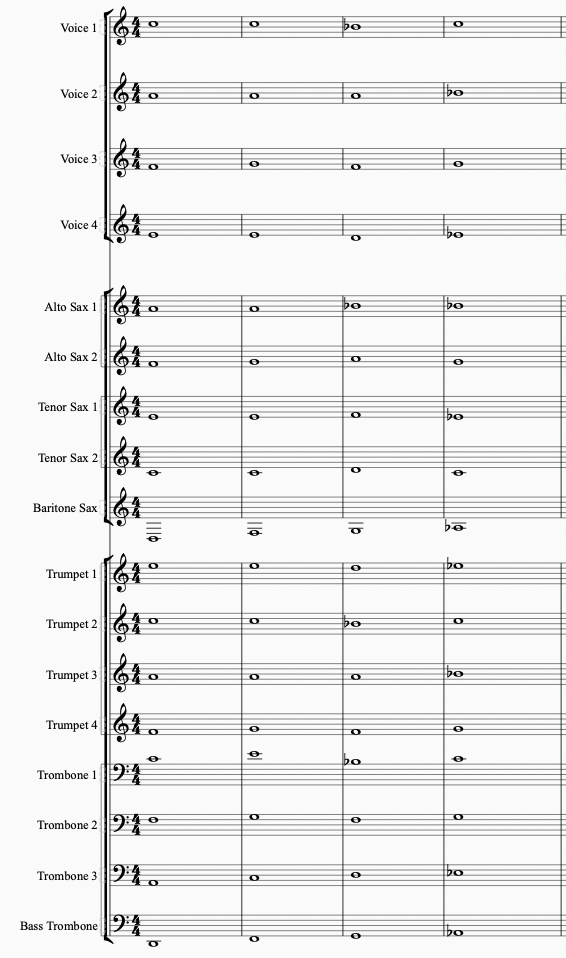

Of course we know that every horn section in itself already has their own little "job" in arranging. If you want to highlight one of these sections especially, then doubling the entire section with your vocalists might be the way to go. If you have a voicing, a melody or a section that you want more powerful, why not put the vocals in the exact same voicing on that as well? The high ranges of the trumpets as well as the low ranges of the trombones can of course be tricky to almost impossible to sing for (female) vocalists, but especially if you have four vocalists with widely different ranges, this margin will get smaller and smaller as well.

With doubling an entire section, the only thing you need to be careful is, is what happens to the other sections that you have not "copied". There will of course still be some doubled notes, as they are inevitable in an arrangement with a lot of horns, but there is also a chance that you drown out the other sections by focusing on one section entirely. But again, if that is your goal because you want to highlight a specific thing within a specific section, then this is a very nice route to go.

In general, doubling the sax section can be a great way to arrange the voices anyways. it doesn't even have to be for reinforcement of a specific thing. As you will see in Example 3, the saxes are all arranged in a quite closed voicing, and still in a very comfortable range for most (female) vocalists. This means that Example 3 would also be a great way to blend the voices into the whole band.

If you were to arrange the saxes out a bit more spread out, or even have the lowest voice double the baritone saxophone, that would mean that the sound of the vocalists will change, and be more noticeable, as well as fortifying for the section you are doubling.

When doubling the trumpet section, you need to of course first take a look at the ranges of the (especially higher playing) trumpets. Anything in lead trumpet range will not be very realistic, except for if you're working with a classicaly trained soprano ;-). I arranged my example (Example 4) in a way, that there should be no problem for the four vocalists to sing all four trumpet parts. Especially when working with different vocalists having different ranges (which is what you ideally want when working with multiple voices, so you can cover more ground range-wise in your arrangements), doubling the trumpet section can be a very interesting feature. playing together with the trumpet will make the voices stick out more than when playing together with the saxophones, this is generally speaking a rule of thumb anyways, as the human voice seems to blend more comfortably with woodwinds like saxophones or clarinets than with more metallic sounding brass instruments like trumpets or trombones.

The last example in this series is Example 5. I wanted the lower end of the arrangement to come through more, so I decided to put the vocals with the trombones. Here it is of course immediately clear, that we can't keep the vocals exactly with the trombones, so I had to rearrange the order of the voicing a bit. The two lower trombone voices are definitely too deep for the female voice. I wanted the deepest voice to sing the bassline with the bass trombone, to give it a bit more depth. Voice 2 then is singing the fifths of that bassline because that is something that always sounds great in lower ranges.

- Example 6 - voices in unison

- Example 7 - voices arranged out in a "modern" four part closed position

- Example 8 - 2/2 voices together, as a kind of "fortified counterpoint"

- Example 9, 10 & 11 - one lead voice and three voices as "backing vocals"

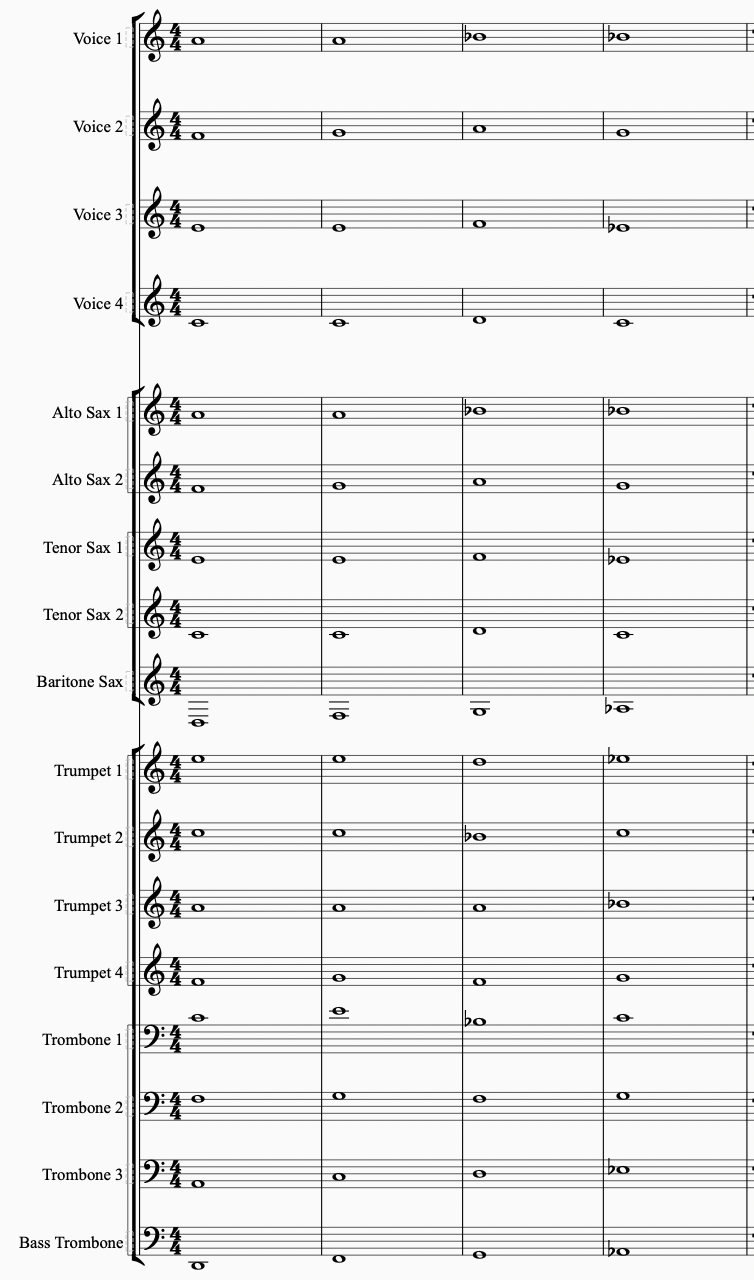

In my piece "Droplets" (Example 6) I wanted the last chorus to be very strong, and the focus of the listener to really be on the lyrics. So I decided to have all four voices singing in unison.

In these cases there are a few things to consider:

- The vocalists should all be aware of the unison, and therefore try to blend in with each other nicely.

- Especially with words ending in consonants, unison can be a very tricky thing (this is obviously only a remark for when writing with lyrics). With enough rehearsing, these endings can be very tight, but if there isn't enough time to get these ending consonants super together, I would advise in one singer singing the consonant by themselves and the rest to end the word on the vowel before. In the audio here it would therefore be one vocalist singing "skyward" for example, while the other three would sing "skywar"

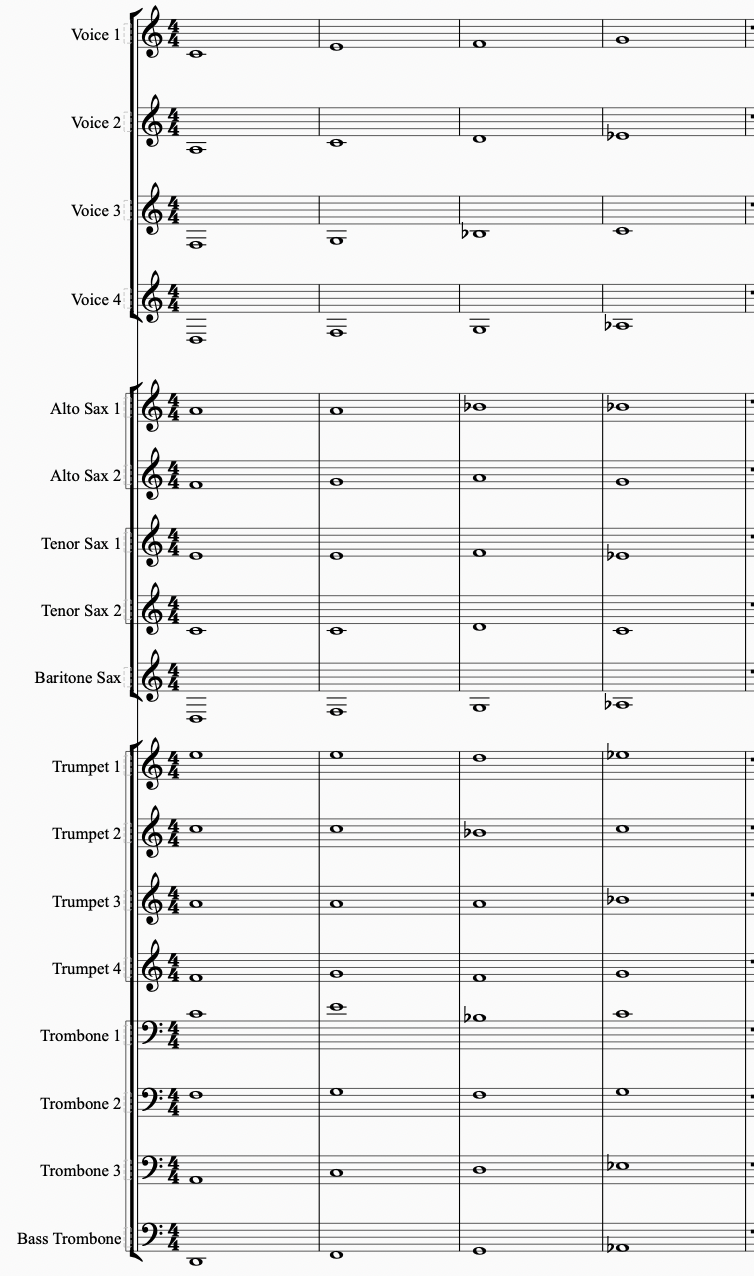

As I often still write pieces with one lead voice in mind, I have collected some examples where I wrote for one lead melody, and three voices working as the "backing vocals" to that melody. With these things, you can get very creative. Sometimes (like in Example 9), I keep the lines of all the vocalists quite fresh and dynamic, but still in a way where the main melody stands out.

If you want a less "dense" approach for these kinds of melodies, you can take a look at Example 10, where you can clearly see Voice 4 being the main melody, and the other three voices backing the voice up with long chord voicings. In Example 10 you can also hear a nice demonstration of doubling the main melody with an instrument out of range of the vocalist, as I had the lead trumpet play along my melody in the recording, but one octave higher. It just shines through together a bit more brilliantly in my opinion.

These last two examples were again from my piece "Allconsuming", whereas the next and last example (Example 11) stems from my piece "Katastrophengesetz". This being a piece fully without lyrics, it made things easier to incorporate all these tactics into my writing and arranging. I will later briefly talk about the use of glissandi with vocalists, and this here is already a good example on how to use the seamless glissandi of the human voice to soften the "faked" glissandi of the horns.

Unique elements of the human voice

- The most obvious thing is of course lyrics. No other instrument can tell a story with words, so that of course is also a tool to use as a composer/arranger.

- Another thing that not all instruments can do smoothly are glissandi. In my writing, I often use the vocalists in my band to support horns in a smooth glissando. Any instrument with valves or keys will not be able to play a smooth glissando. Next to vocalists, you can also use trombones in a lower range or any ranged string instruments to support in glissandi. With trombones you just need to be aware of the positions and if your desired glissando works, with string instruments it's of course a thing about the range of one string that will give you the range of the glissando. With a vocalist the only thing that could present a little bit of an obstacle is if there is a big difference between their head and chest voice, so there is a bit of a chance of a crack happening in the voice, or a difference in sound.

- Another thing you can experiment with with vocalists are extended techniques. This of course widely differs from singer to singer, and that's why I again implore you to get to know the vocalist(s) you're working with and get to know their voice up close and personal. The human voice is the most intimate and personal instruments, as it is literally in our bodies, and knowing this instrument well can really help you out. I have collected a few extended techniques that can add a cool soundscape or special effect to your music that should not be too hard for any vocalist to do:

- Breath - meaning using loud in - and exhaling as a sound effect

- Glottal sounds like vocal frys (a very low register in the voice, and a rattling, bubbling sound produced by not fully closing your glottis)2

- Ululation - a long, wavering, high-pitched vocal sound resembling a howl with a trilling quality. It is produced by emitting a high-pitched loud voice accompanied with a rapid back-and-forth movement of the tongue and the uvula. Ululation is practiced in certain styles of singing, as well as in communal ritual events, used to express strong emotion.2

- Trills and Tremolos

- Belting

- Very airy sound, almost no "notes"

Some more technically challenging, but cool ideas and additions would be:

-

- Growling and Screaming

- Multiphonics

- Under - and Overtones

Using Phonetics to your advantage

In my research, I have found that a basic knowledge of phonetics can be very useful in writing for voice, especially when writing for voice without lyrics. Merriam-Webster defines phonetics as "the system of speech sounds of a language or group of languages". 1 Finding out the words to describe certain sounds that you would like to hear can be highly beneficial to your writing (and rehearsal) progress. In these following paragraphs, I will explain the most used phonetics I have encountered when singing.

Of course you don't have to use all the specific lingo of phonetics, as most people don't know these things very well as well, but my goal is to give you an insight in how sound production works, and how this can help you determine what vowels and/or consonants to choose when writing "instrumentally" for your vocalist(s).

Vowels

There are five vowels in the english language: /a,e,i,o,u/ (and sometimes y). We can roughly differentiate between "close/high" and "open/low" vowels, where these names are representing of the position of the tongue during the production of a vowel. Examples for closed vowels are i in “machine” and u in “rule” and for open vowels a in “father” or “had”3.

The most important chart for arrangers is definitely the chart about vowel sounds on the right. This is what you can keep in the back of your head when writing lines for vocalists without lyrics. The type of vowel hugely influences in how comfortable a note feels and sounds with the voice. This of course differs from singer to singer. Vocalists of course also train their vowel production very heavily, trying to have a universal sound over all the vowels in all the ranges. But there will of course still be differences in sounds especially in higher ranged melody writing.

If you don't really mind what vowel the vocalists should sing during an instrumental line, then I suggest using these charts to help you choose the vowel best fitting for your specific lines. On the other hand, if you have a quite clear sound in mind, then it goes the other way around, where it is good for you to write lines according to where the vowel you have in mind is situated.

If you want to save time in rehearsals, then I strongly suggest you already thinking about what exactly the vocalists should sing. This, combined with you knowing the range of your vocalists will make it easy for you to write lines that are very clear for the perfroming vocalist.

Plosives

"Plosive consonants are made by completely blocking the flow of air as it leaves the body, normally followed by releasing the air. English pronounciation contains 6 plosive phonemes: /p,b,t,d,k,g/"

The sounds /b,d,g/ are voiced; they are pronounced with vibration in the vocal cords. /p,t,k/ are voiceless; they are produced with air only. The voiceless plosives are often aspirated (produced with a puff of air) in English pronunciation.7

Image source: 8

Image source: 8

I have found that next to open vowels (or monophtongs), plosives can be used in the most creative ways when writing instrumentally for vocals. In many of my pieces, I used plosives very deliberatly to get the kind of attack I wanted. In bell-forms for example, I advise using voiced plosives like "b" or "d" infront of monophtongs, to have a softer attack with a less aggressive start of the note, yet still enough "punch" to blend in nicely with for example saxophones, who also kind of form a voiced plosive ("d") when they form a note.

If the voices are together with brass, it might be a good idea to have them use unvoiced plosives. Especially "t" sounds great with higher brass, where the attack can also get quite "aggressive", especially the higher the notes are.

In conclusion: Know who you're writing for, know the sound you want to create, and be open for new sounds coming into your musical world!

Thank you for reading through this little handbook! I thoroughly enjoyed researching about this topic and compiling all the things I discovered into this little website for you to look at. I hope this collection of tools will help you get inspired in writing for vocalists!

I am always open for more questions and ideas about writing and arranging for the human voice, so don't hesitate to contact me! :-)

1 “Phonetics.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/phonetics. Accessed 18 Feb. 2023.

2 "Vocal extended technique." Wikipedia, 19 Sep. 2022, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extended_vocal_technique Accessed 18 Feb 2023.

3 "Vowel". Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. Encyclopedia Britannica, 14 Feb. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/vowel. Accessed 18 Feb. 2023.

4 "Vowel Height." The Mimic Method. https://www.britannica.com/topic/vowel. Accessed 18 Feb. 2023.

5 "Cardinal Vowels". Wikimedia Commons. 11 Feb 2008, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cardinal_vowel_tongue_position-front.svg. Accessed 18 Feb. 2023.

6 "Vowel Shapes". singeo. https://www.singeo.com/chorus/vowels-the-singers-secret-weapon/. Accessed 18 Feb. 2023.

7 “Plosive Consonant Sounds - the Sound of English.” The Sound of English, Pronunciation Studio Ltd, https://thesoundofenglish.org/plosives/. Accessed 17 Jan. 2023