The Viennese violone in the orchestra

This chapter covers the use of the Viennese violone in orchestral music, and gives some reflection on this, and different interpretations of possible use.

From the available ensemble pieces of the classical period, I first analyzed the style of the divertimento, popular in the 18th century. I then chose to analyze the symphonies of Haydn and Sperger because of the particular relationship they have with the Viennese violone. I will use them to identify the Viennese idiom used in their compositions.

This choice does not suggest that the other ensemble pieces composed in that period in the Austrian Habsburg Empire were not played on Viennese violone, but I chose to concentrate on the transitional period after its development. However, the Viennese violone was certainly used for the musical ensemble works of the composers of this region, including of course the symphonies of Mozart.

Divertimenti

The divertimento is a particularly important style which flourished in the classical period. The term “divertimento” comes from the Italian word “divertire”, which means “to amuse” or “to entertain”. Divertimentos were typically light, entertaining pieces of music that were intended for social occasions or for simply enjoying as background music. They were often composed for small ensembles and were a precursor to the symphony and the string quartet. The style of the divertimento also played a significant role in the development of the Viennese violone in small ensembles. In the divertimento, the violone had a predominant role, in contrast to the cello, which was practically non-existent in this style or is relegated to a simple bass part. The divertimento offered the Viennese violone the possibility of improvising and explores its technical capacities. This popular style can, according to Focht, be divided into two sections in the Viennese violone period. The divertimenti around 1740, at the beginning of the reign of Maria-Theresa were stylistically more improvised. Subsequently, around 1760 and 1770, they became more formalized, and with variable instrumentation. With the flourishing technique of the Viennese violone, bigger solo pieces written as improvisations also appeared in the trio sections of the menuets.[1] These virtuosic sections, written as they were improvised, were also included in the solo music for the Viennese violone, for example, in the trio of the second quartet for solo double bass of Franz Anton Hoffmeister.

The divertimenti allowed the Viennese violone players to free themselves in their instrumental playing. They also played an important role in the development of the Viennese technique and the soloistic role in this music. Unfortunately, musical tastes changed at the beginning of the 19th century. The divertimento practice, already in decline outside the Habsburg Empire, became stylistically old-fashioned. The political and cultural life changed with the accession to power of Joseph II and the growing practice of music-making by amateur musicians. Joseph II himself played the cello as an amateur. With “the amateurs” came a taste for more bourgeois concerts, in the salons; string quartets and quintets became fashionable. The Viennese violone relinquished the soloistic role and was relegated to the simple “bass” line, while the cello was brought to the forefront. The same period also saw the rise of the music printing industry, which left little room for the improvisation practiced in the early divertimenti. Music became more scholastic, and its instrumentation more precise, making it easier to play for non-professionals.

The Viennese violone solos in Joseph Haydn’s symphonies

In Joseph Haydn’s symphonic works, we have clear and reliable evidence of the use of the Viennese-tuned violone in the orchestra.

Of the many symphonies he wrote, six include a solo written specifically for the Viennese violone.This approach was new at the time; the first example of this soloistic exposition of the double bass is Telemann's “Grillen symphony” composed in 1750, only ten years before Haydn's first solo. This symphony is a “concert with nine parts” including two solo parts for two double basses: “première bassecontre” and “seconde bassecontre”.[2] In the scores of Haydn’s symphonies, the words “Violone solo” gives a clear indication of his intentions. These symphonies are played tutti with the whole ensemble, then suddenly Haydn gives the Viennese violone a soloistic role accompanied by the other instrumentalists. These symphonies are the 6th, 7th, 8th, 31st, 45th, and 72nd. The solos of five of them were composed for the Viennese violone player Johann Georg Schwenda, and one of them (the solo of symphony 45th) for Johann Dietzl. Both Violone players worked in the Esterházy Chapel when Joseph Haydn composed these six symphonies. Schwenda played at Esterházy from 1761 to at least 1765. He was mentioned in the paid records of the orchestra as a second bassoonist and violone player. It is also likely that Haydn composed his lost concerto for him in 1763.[3] Dietzl appeared in the salary records of the Esterházy ensemble from 1775 onwards. His presence in the ensemble was divided into two periods. He stayed until 1790, and then returned from 1802 until he died in 1806. In the meantime, Johann Dietzl played in the opera orchestra in Vienna. It was also there that he gave the first performance of Beethoven’s Septet op.20 for strings, and winds, in April 1800.[4]

The solos of the 6th, 7th, and 8th symphonies are relatively straight-forward. They do not show all the possibilities offered by the Viennese tuning. These symphonies are respectively called “Le Matin”, “Le Midi”, and “Le Soir”. The three Viennese violone solos are present in the trio of each Menuet of the symphonies. In his analysis of these solos, Jozef Focht told us that the solos can technically be played with D Major tuning but fit more with the d minor tuning which was used for the church music and the divertimenti.[5] Focht’s analysis is based on the fact that the trios are in minor or neutral tonalities: d minor for two of them and C Major for one of them. It makes more sense, in this case, to use the d minor tuning also for the Viennese instrument.[6] It is technically easier, and gives a more resonant sound and colorful playing.

In the solo of the 31st symphony “The Hornsignal”, and in the 72nd symphony, Haydn was more aware of the possibilities offered by the Viennese tuning. The style of composition is more developed, and we can completely identify the Viennese idioms in it. There is no doubt that here the solos are composed for D Major tuning. In these two symphonies, the solos are also placed differently from the 6th, 7th, and 8th symphonies. Now, they are present in the variations of the last movements, and offer a more concertante way of playing.[7]

The solo of the 45th symphony is more complex and asks for more technical skills of the player. This 45th symphony, also known as the “Farewell” symphony, was performed for the first time in 1772. It is considered one of the most famous works of Haydn. The symphony is known for its unusual ending, in which each musician, one by one, puts down their instrument and leaves the stage until only two violins are left playing. This was intended as a musical depiction of the departure of the musicians from Prince Esterházy's summer palace, where they would typically spend the summer months composing and performing music for the prince and his guests. The Viennese violone solo takes place here, at the end of the symphony, just before the violone player must stop playing and leave the stage. It is probably Johann Dietzl who played the Viennese violone solo at the first performance. Haydn said of Dietzl in 1803, concerning his interpretation of his solo:

“My Humble opinion would be, ... that Jean Dorzel, as the only good Contra Bassist in Vienna and the whole Kingdom of Hungary, should be graciously granted his request.[8]”

The specific use of the Viennese tuning by Haydn, and the stylistic development in his compositions, show that Haydn learned the possibilities of the tuning. We observe the same thing in his divertimenti.

Johannes Matthias Sperger (1750-1812)

Among the composers and players of the Viennese period, the most prolific is Johannes Matthias Sperger. Sperger, known for his virtuosity on the instrument, is interesting to mention in this research because of his connection with orchestral music. Indeed, he composed an enormous number of symphonies, which have been carefully preserved, as most of his manuscripts, in the Schwerin library. From 1789 to his death in 1812, Sperger was engaged as the first double bass player at the court of Friedrich Franz 1st the Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, in Ludwigslust. After his death, his manuscript collection remained there. In addition to his own works, this collection also contains a full collection of other important composer’s pieces for Viennese violone carefully collected by Sperger and containing his annotations and handwritten cadenzas. Sperger's manuscripts give valuable first-hand information on the denomination of the 16' instrument used, and a good analysis of the orchestral and instrumental practice at the time. For this research work, it was important to analyze his symphonies to see if a specific use of the Viennese violone in his orchestral music could be discovered. As an acknowledged virtuoso on the instrument, he is one of the composers who has the most complete knowledge of the instrument’s capabilities.

43 symphonies are preserved in the Schwerin library and are cataloged by Meier. Number 44 is a set of parts preserved in Basel and in Sperger’s catalog the composer mentioned a 45th symphony, but it has not yet been found. I examined all the symphonies of Sperger, except the five last ones, preserved in Schwerin’s library. The first thing that can be said is that they are incredibly well-preserved. Their writing is clear, without many blemishes, some pieces of sheet music have been replaced and new ones have been stitched or nailed to the old scores.

There were no violone solos in the thirty-eight Sperger symphonies I have analyzed. One would have thought that he would include solos for this instrument, but instead, there are beautiful solos for viola, bassoon, wind, and violin.

What I saw from the nomenclature of instruments in the symphonies is that “basso” is not used solely for the 16' instrument but is a generic term including bassoons, celli, and basses (violones). The term used for the 16' instrument is mainly “violone”. This is noticeable in the “Finale” of the symphony labeled MUS 5173/5 by the Schwerin’s library, where Sperger makes a crescendo with successive entrances in the bass voice instruments. Sperger gives successive entrances first to the cello marked “f”, then to the bassoon marked “ff”, and finally to the violone, which he asks to play “fff”.

The term “contrabasso” appeared in the separate parts conserved from the last symphonies. In the “basso” line, as mentioned, Sperger divided already sometimes the line between the cello, the bassoon, and the violone.

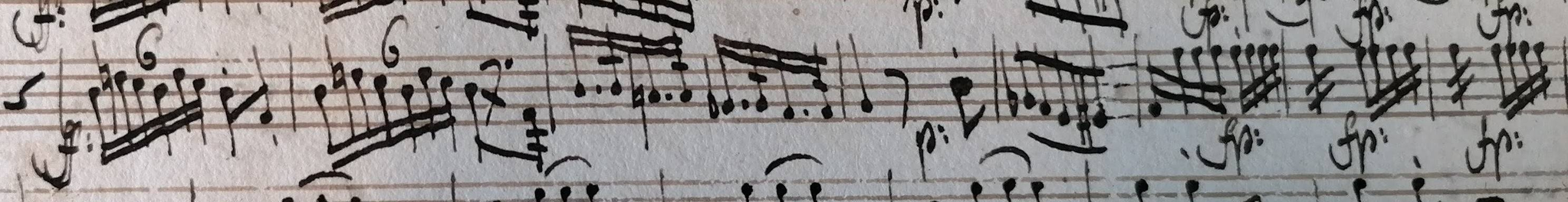

If we analyze his writing further, we can find idioms of the classical writing style in the bass line of his symphonies, but also similarities with the writing style he used in his solo pieces for the Viennese violone. It is interesting to note that certain passages are used in both situations. In the first movement “Allegro Con Expressione” of his symphony labeled MUS 5158, we have a motif in the bars 12-13 of the bass line that we also find in the bass line of his 18th concerto in C minor for solo Viennese violone. We can also find various examples of rhythmic or musical patterns used in other solo works, such as the ascending scale with triplets ending at the top with an “a”, which could be played in harmony with the Viennese violone. We found many passages where the Viennese violone plays arpeggios or broken arpeggios and where the orchestra can benefit from the resonance of its tuning. Finally, we find in Sperger's writing many detailed and articulate passages in fast-tempo movements. Some of these passages are a sort of ornamentation, and this treatment is also found in his solo work for the Viennese violone.

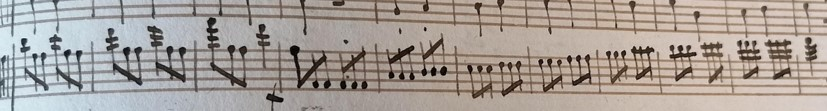

Figure 12. “Pattern with pedal note and pattern of an ascending scale with triplets.” These patterns are used in several solo pieces in the Viennese violone repertoire.

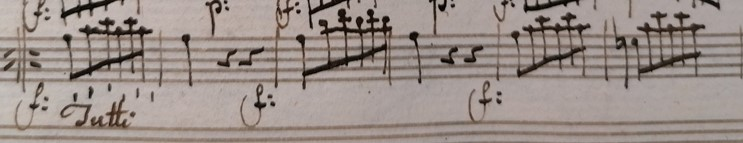

Figure 14. In Sperger's 18th concerto in C minor for Viennese violone solo, we find a very similar passage in bars 208-209 of the first movement. In this passage the composer has used the same motif in the same way. In both cases the motif is played tutti to punctuate the musical phrase.

In conclusion, as in Sperger’s solo music, we found in his orchestral music the presence of the Viennese violone: the different musical patterns and his writing style, and the express mention of “violone”. This makes his work a valuable source of writing specifically for Viennese violone in orchestral music, even though there is no written proof of his intention.

The fact that there are no difficult solos for the violone in the symphonies, could be because Sperger knew that the pieces were not dedicated to a virtuoso violone player in the specific orchestra for which the symphony was commissioned.

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1828)

The use, and the possible use of the Viennese-tuned instruments in Beethoven’s music is, for me, more complicated.

In Beethoven’s music, there is a change in the writing style of the bass line, and the treatment of the sound of the 8' and 16' bass instruments changed compared to the compositional style of Haydn and Mozart. Gradually, there is a clear distinction between cello and double bass lines. Beethoven went as far as the magnificent low-strings solo in his 9th symphony. Compared to Haydn's violone solos, written for one violone, this one includes both basses and cellos, has a 19th century assertive style, and reflects the expression of the low human voice.

How can we historically link the Viennese tuning to Beethoven?

The compositional dates of Beethoven’s symphonies are:

The 1st symphony was performed for the first time in 1800

The 2nd symphony was composed in Vienna between 1801-1802

The 3rd symphony 1803-1804

The 4th symphony 1806-1807

The 5th symphony 1806-1808

The 6th symphony 1805-1808

The 7th symphony 1811-1812

The 8th symphony 1812

The 9th symphony 1822-1824

What we know of the symphonies of Beethoven is that they were composed in the first part of the 19th century, when the Viennese tuning was still in use by some players in the Viennese area. We also have evidence that, when he was in Vienna, Beethoven knew and met Haydn and Albrechtsberger, who were both in contact with the Viennese tuning. In the first representation of Beethoven’s Septet on 2 April 1800, the 16' instrument was played by the Viennese violone player Johann Dietzl.[9] In the Viennese Concert calendar from 1761-1810, as established by the contemporary musicologist Mary Sue Morrow, the different players of Beethoven’s Septet are cited as:

“Herr Schuppanzigh, Schreiber, Schindlöcker, Bähr, Nickel, Matuschek, and Dietzel.[10]”

In the “Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung n°3” of 15 October 1800, we have a review of this same Beethoven concert played in Vienna on 2 April 1800. It is mentioned there that, for this concert, he played a new piano concerto from his composition, and after, was played his Septet and a symphony. The symphony performed on that day, given the year of composition, is his 1st symphony.[11] The author is quite critical of the orchestral performance in the article. As we understand, the orchestra Beethoven chose for the interpretation of his 1st symphony did not play so well. Beethoven chose the orchestra of the Italian opera that was apparently the best orchestra in Vienna at that time. There were two orchestras active in Vienna in that period: the orchestra of the Italian opera and the orchestra of the German opera. The first article in the “Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung n°3” is an article giving reviews about the performance of the singers and the orchestra of the Italian opera in Vienna. The second article in this musical revue gives us insight into the German opera, and the third article “Oeffentliche Akademien” (“Public Academy”) talks about the concert of Beethoven. Concerning the presentation of Beethoven’s concert, the author of the critique refers to an article mentioned before in the review concerning the playing of the orchestra. In the first article of the review about the Italian opera in Vienna, this is said concerning the orchestra:

“As for the violones, one could wish that all five of them would not be five-stringers and that the gentlemen would be a little quieter. During loud Fortes, they rasp and rumble rather than produce a clear and percussive sound, which would promote the ensemble.[12]”

In the original German text, the author used the term “violons” which is already an indication of the instrument used. We understand that he is talking about 5-stringed instruments. However, in Vienna in 1800, no other type of 5-string tuning was used (cf. the writings of Albrechtsberger), except for the Viennese violone, which was still in use. We can therefore assume that the only instrument that could be discussed here is a Viennese tuned violone.

At the beginning of the 19th century, Dr. Nicolai describes several double bass tunings in his article “Das Spiel auf dem Contrabass.” published in the “Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung n°16” on the 17th of April 1816. Nicolai mentions the 5-string Viennese tuning, various 3-string tuning, and later on, the fourths tuning, of which he mentions the version with low D “D, A, d, g” as being the best for large instruments.[13]

In a book of letters left by Sir George Smart, an English conductor, we find a letter dated of the 11th September 1825 about his travel to Vienna to discuss the performance of the 9th symphony of Beethoven with the composer. Sir George Smart wrote:

“Mr Mittag first took me to St. Michael’s church, at 10, […] The double-basses here [Vienna] had 4 strings and Mittag said some had 5, but with 3 Dragonetti does more than I have yet heard.[14]”

This letter shows that some of the 5-string Viennese violones were still present in Vienna in 1825, but also corroborates the fact that they were progressively disappearing in favor of the fourth tuning “F, A, d, g”.

The contemporary bassist, Joseph Focht, also writes this about Beethoven’s 3rd symphony and the use of a lower fourth string as “D, A, d, g”:

“As early as the turn of the 19th century, a variant of the fourth tuning with a low D' string appeared. The most popular example of its use is the fugue theme from the final movement of Beethoven's third symphony, Eroica.[15]”

“Beethoven's 3rd Symphony Eroica op. 55 also requires the depth limit D in the double bass part.[16]”

Stephen George Buckley writes about the analysis of Beethoven’s works regarding the bass line and considered the consistency of his writing without significatively going under the range of the low “F” in the bass part. I will quote his conclusion for op. 15 to op. 50.:

“Collectively these eight works demonstrate without question that Beethoven began writing for the double bass very carefully within the confines of the conventions he inherited from the Viennese late-classical period. Of the twenty movements or single movement works in this group, only three contain notes written below F; two if op. 43 is excluded, where the notes below F are clearly indicated for cello only. The total number of notes below F for cello and double bass combined is 11; total number of notes below F for double bass is 7. [...] After this point, Beethoven’s handling of the bass part changed in certain respects.[17]”

For the works after this op. 50, he analyses that the use of the bass instrument and the range of the low notes change radically. For Buckley, this is also a significant reason to think that the Viennese tuning was no longer in use, but I would not think in this way. The work of Buckley and his way of analyzing Beethoven’s music give us a way to make our reflections grow about a possible change in Beethoven's compositions. The only problem is that he took into consideration editions of the works of Beethoven as primary sources and not manuscripts. The manuscripts can be now, for most of them, available in the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin and at the Beethoven Haus in Bonn. Some sketches are also available in the BNF in Paris. So, to consider his supposition, we need to verify his theory by looking into the manuscript of the symphony. I have also to mention that this analysis is just a way to go closer to what could have been done during that period. As we know, the Viennese bass players were also changing the lowest string of their instrument to E, Eb, or D. The low “F” boundary doesn't necessarily means that the passages were played on Viennese tuning. In that sense, the thesis of Buckley can be used to give us an indication of a change in the writing convention of Beethoven, and when it appeared, but not that he would have written for the Viennese violone.

All this historical evidence does not necessarily show that Beethoven intentionally wrote for the Viennese tuning, but it does show that some of his works might still have been played in this tuning in the early 19th century, even though this system was no longer universally accepted.

Analysis of my personal experiences as a professional player for some of Beethoven’s symphonies.

I have played in Viennese tuning, in the 2nd, 4th, and 8th Symphonies of Beethoven in professional HIP orchestras:

· For the 2nd symphony, we were three players. Two players were playing with a fourths tuning “E, A, d, g” and “C, E, A, d, g”, and I was playing in Viennese tuning. In another project, we were two players, one in Viennese and one in fourth tuning “D, A, d, g”.

· For the 4th symphony, we were two players. I was playing in Viennese tuning and the second player was playing with a fourth tuning with a low “F” instead of a low “E”. professionnal recording with the Kammerorchester I TEMPI

For the 8th symphony, we were 5 players. After having had some rehearsal time with 4 basses in the fourths tuning, and 1 bass in the Viennese tuning, I switched to the fourths tuning with low “D” as “D, A, d, g”.

Firstly, I can attest that these three symphonies are technically playable in Viennese tuning. Secondly, I could not experiment with playing an orchestral session with all the players with the Viennese tuning because of the impossibility of having enough instruments.

Why did I change the tuning for the 8th symphony?

Although it was possible to play the 8th symphony with the Viennese tuning technique, I realized during the rehearsal that I was using the wrong aesthetic for the symphony. By aesthetics, I mean that as an experienced HIP player, I wanted to achieve a certain quality of sound and power that I could not get. The Viennese tuning gives the bass a brighter color because of the D-major tuning, and the frets that accentuate the upper harmonics. The 19th century fourths-tuned instrument has more fundament in the sound. In addition, the instrument is more powerful because of the lower tension on the bass and because of different internal construction.

For this symphony, the bass line must give power and dynamism to the whole orchestra, starting right from the opening with the long pedal notes of the chord and repeated pitch notes that set up the key of F-Major (1mvt “Allegro vivace e con brio” bar 1 and bars 12-32). In the last movement, we also have the fugato entry with a striking bass solo before the great fermata (bar 281) of the orchestra, which demands a great deal of “declamation” in the sound.

In my opinion, this power of the bass line develops throughout Beethoven’s symphonies. I felt that the way of projecting the sound had to change from the 3rd symphony onwards and certainly from the 5th. This development also involves a different conception of the music, which becomes more pictorial and reaches its climax with the solo of the basses and the cellos in the 9th symphony. For this solo, a completely different style of writing is used from the symphonies of Haydn and Mozart. As I said earlier, the solo is for both celli and basses. It has a 19th century assertive style. The musical line is vocal and reflects the expression of the low human voice. The celli and basses, in this solo, take on the role of a solo opera bass singer accompanied by the orchestra.

For the 4th symphony, we also needed more bass fundament. In this case, what I liked with the Viennese tuning was the low “F”. If you take a fast tempo in the 4th movement, it is technically tricky to have a low “D” as bass (for example). At a technical level, the Viennese tuning is possible but increasingly complicated if the conductor takes a fast tempo. My experience was that with two players, and a mixed tuning, as may have been the case at the time, both Viennese tuning and fourth tuning are possible.

I do not have the same experience with all the symphonies, but I can say that for the 2nd symphony, I did not miss anything as a musician by playing it on Viennese tuning. From my point of view, the Viennese tuning made it easier to play. For example, the Viennese tuning allows the scales at the beginning to be clearer because of the frets. You also do not have much shifting, and you can give more of the idea of fireworks, represented by the scales. In this symphony of Beethoven, you also found a lot of classical patterns in a tonality that suits the Viennese tuning: “D Major”. Il will give more details in the practical approach chapter.

Beethoven's writing style evolved rapidly and became stronger, and more projective in the wind and brass section. His music became also influenced by the revolutionary ideas appearing in France and by Napoleon. Regarding the Viennese tuning, it can be assumed that Beethoven knew of its existence through his acquaintances, his studies, and the Viennese violone players involved in his septet, and his 1st symphony.

However, there is no definitive historical evidence of Beethoven's intention to use a specific tuning system in his musical works. By this time in Vienna, as we understand from Albrechtsberger’s writings, the D-Major tuning was becoming unfashionable, and the new generation was already tuning their basses to fourths. The players likely had mixed tunings in the orchestra at that time. This practice was usual at that time in several ensembles. We have records of the seating plan of the Paris Opéra Orchestra in 1820 with mixed three strings and fourth strings basses, some sources in Britain, and some positive words of Hector Berlioz in 1844, for example.[18] The players at the time of Beethoven probably switched tuning as soon as they realized that it was stylistically or technically necessary. This was also influenced by the development of the musical educational system. With this historical point in mind, I will compare some passages from Beethoven’s symphonies and give some personal conclusions for practical application.

Franz Schubert is an interesting figure to study in the context of the Viennese violone school because he lived and worked in Vienna during the last development phase of this school. He received a conservative musical education at the Stadtkonvikt school in Vienna between 1808 and 1813, which would have exposed him to the music and techniques of the Viennese violone school. Some of his earliest compositions date from this period. Additionally, he was known to have performed as a violist and he likely had contact with violone players during his time in Vienna. This could have further influenced his understanding and use of this instrument. His close connection to the Esterházy family, one of the most prominent musical patrons of the time, gave him the opportunity to be exposed to and interact with some of the most influential musicians and composers of the day. In addition, Schubert was known for his innovative and forward-thinking approach to composition linked to the romantic movement of the 19th century. This makes it interesting to investigate how he incorporated previous traditional elements such as the Viennese tuning into his works. By examining Schubert's compositions, we can better understand if he could have used intentionally a specific tuning for the bass as the Viennese tuning, or not.

There is no evidence of a direct relationship between the symphonic work of Schubert and the Viennese tuning. By contrast, there is historical evidence in his chamber music. Schubert’s quintet “The Trout” was composed for the Viennese tuning bass player Sylvestre Paumgartner.

The “Trout” Quintet

Franz Schubert's “Trout” Quintet in A Major is a chamber work composed between 1819 and 1825 during Schubert's travels to Steyr (Upper Austria). Steyr is the city of the Austrian Viennese violone player Sylvestre Paumgartner (1763-1841), who inspired Schubert’s composition of the bass part of the quintet. Indeed, Paumgartner found Schubert's Lied “Die Forelle” D550 very beautiful and expressly asked the composer to write a work around it. This is mentioned in a letter by Albert Stadler (1794-1888) to Ferdinand Luib in 1858:

“You are probably familiar with Schubert's Quintuor for pianoforte, violin, viola, cello, and double bass with the variations on his 'Trout'. [Schubert’s Lied Die Forelle D550] He wrote it at the special request of my friend Sylvester Paumgartner, who was delighted with the delightful little song. According to his wishes, the quintuor had to retain the structure and instrumentation of Hummel's quintet, [recte] septuors, which was still new at the time. Schubert was soon done with it, he kept the division himself.[19]”

The quintet referred to in Stadler's letter is the double-bass quintet that the pianist Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837) arranged in 1816 from his Septet op. 74.[20] Albert Stadler also made the only contemporary handwritten copy of Schubert's autograph of the quintet that exists. In this copy, there is the presence of a 16’ part with the mention “violone” (which will later become double bass):

“Gran Quintetto per il Piano ForteViolino Viola Violoncello e Violone composto e dedicato al Signor Silvestro Baumgartner da Francesco Schubert[21]”

Although the autographed manuscript of the quintet has been lost, it is believed that Albert Stadler retained the original title and that Schubert composed it for a double bass player.

The first publication of the quintet was made in 1829 by Carl Czerny after Schubert's death. Cerny published it with the possibility of playing the bass line by a second cello to gain greater commercial exposure. The popularity of the cello in the mid-19th century may have influenced Czerny in this decision.[22] Today, the work is performed with a double bass instead of a second cello despite the first edition of Czerny, and it remains a staple of the chamber music repertoire. The “Trout” Quintet is known for its tuneful melodies, lively rhythms, and charming use of variation form, and it continues to be enjoyed by audiences and musicians alike.

In his book, Jozef Focht provides valuable insights into how Schubert used the Viennese tuning in this composition. After a thorough analysis of the technical issues of the bass part, and the differences between the manuscript of Stadler and Czerny’s first edition, Jozef Focht gives this conclusion:

“When playing the bass part on the modern-tuned double bass, the huge difference in technical difficulty between the predominantly modest fingering requirements in all five movements and the few, particularly difficult passages is striking. These are bars 181ff in the first movement, as well as the fourth variation of the trout movement. The former passage can be performed in the Viennese D major tuning in the usual register without significant changes of position or other difficulties, while the fingering of the latter in the tuning DA d f# a is so simplified that it can also be mastered by a layman.[23]”

The conclusion of Jozef Focht makes even more sense as, historically, Paumgartner was a Viennese tuning violone player. Jozef Focht considers that there is no reference to the Viennese tuning in other chamber music works from Schubert.[24] Moreover, until now, no historical evidence shows that Schubert composed other pieces, thinking of a specific violone player or for a specific situation implying the Viennese violone.

Personal practical approach

I would like to experiment with the use of the Viennese tuning in some other of Schubert’s works from the same composition period. if we consider that Schubert's “Trout” quintet was written for the Viennese violone and that Schubert was familiar with the tradition of the Viennese tuning in D-Major, it makes sense to examine his symphonic works composed before or around its supposed composition date between 1819 and 1825. This would certainly correspond to his first composition period when he wrote his first six symphonies. The 6th symphony was composed in 1818, just before Schubert’s first travel to Steyr. The chosen keys are not extreme, and are well-suited for the Viennese tuning. These keys are Bb-Major, B-minor, C-Major, C-minor, D-Major, and E-Major. Additionally, there are also some fragments of unfinished works in D Major.

All these observations show that, historically, it is possible that Schubert used the Viennese violone in some of his early symphonic works. There is also sufficient evidence to suggest that the bass part of the “Trout” quintet was composed with the knowledge of the Viennese tuned violone’s capabilities. Further practical examination of these works may provide a better understanding of Schubert's compositions and whether, as a player, it is consistent to use the Viennese tuning in their performance. In the next chapter, I will make a sound and technical comparison between selected extracts of his chamber and symphonic music, played on Viennese violone, and on fourths tuned bass.

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

For Mendelssohn, my approach is a bit different from that of Schubert and Beethoven. Mendelssohn did not grow up in Vienna but traveled there.

I wished to look at the orchestral works of Mendelssohn because his orchestral writing is reflecting the classical period of composition. He received a precise education inspired by the old masters like Bach, CPE Bach, Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. His music is light and bright, and reflects the classical structures, and patterns. We have different evidence of that, such as in the early string symphonies, as well as in the other mature works of Mendelssohn. The Viennese tuning reflects also this light and bright color into the orchestral music. We can identify this in the classical symphonies of Mozart and Haydn.

Through experiments, I would like to propose a practical approach to Viennese tuning for Mendelssohn's music. Would it be interesting to use Viennese tuning to reflect the color of the classical aesthetics of Mendelssohn's works? Would it be a perfect link to Mendelssohn's written way of composing? I will try to answer these questions in my practical chapter.

[1] Jozef Focht, Der Wiener Kontrabass, Spieltechnik und Aufführungspraxis Musik und Instrumente (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1999), 10.

[2] Joëlle Morton, “Haydn's Missing Double Bass Concerto,” Bass World, International Society of Bassists, XXII 3, 1998, 7.

[3] Jozef Focht, Der Wiener Kontrabass, Spieltechnik und Aufführungspraxis Musik und Instrumente (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1999), 195.

[4] Ibid, 177; Mary Sue Morrow, Concert Life in Haydn’s Vienna: Aspects of a Developing Musical and Social Institution (Stuyvesant NY: Pendragon, 1989), 304.

[5] Jozef Focht, Der Wiener Kontrabass, Spieltechnik und Aufführungspraxis Musik und Instrumente (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1999), 106 and 195.

[8] “Meine ohnmassgebliche Meinung wäre, ... dem Jean Dörzel als den einzigen guten Contra Bassisten in wienn und ganzen Königreich Ungarn seine Bitte in gnaden verabfolgen zu lassen.” Ibid, 177.

[9] Ibid, 177; Mary Sue Morrow, Concert Life in Haydn’s Vienna: Aspects of a Developing Musical and Social Institution (Stuyvesant NY: Pendragon, 1989), 304.

[10] Mary Sue Morrow, Concert Life in Haydn’s Vienna: Aspects of a Developing Musical and Social Institution (Stuyvesant NY: Pendragon, 1989), 304.

[12] “Bey den Violons wäre zu wünschen, dass nicht alle 5, fünfsaitig, und die Herren etwas weniger gemachlich wären. Bey grossem Forte hört man mehr drein reissen und Rumpeln, als deutlichen, durchdringenden Basston, der das Ganze erheben könnte.” Ibid, col. 42.

[14] British Library, Department of Manuscripts, Add. MS 41774, f. 26r, [With Mr Mittag at St Stephen’s Church, Vienna, Sunday 11 September 1825].

[15] Jozef Focht, Der Wiener Kontrabass, Spieltechnik und Aufführungspraxis Musik und Instrumente (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1999), 39.

[17] Stephen George Buckley, “Beethoven's Double Bass Parts: The Viennese Violone and the Problem of Lower Compass” (PhD diss., Rice University, 2013), 73.

[19] “Schuberts Quintuor für Pianoforte, Violine, Viola, Cello und Kontrabass mit den Variationen über seine 'Forelle' ist Ihnen wahrscheinlich bekannt. Er schrieb sie auf besonderes Ersuchen meines Freundes Sylvester Paumgartner, der über das köstliche Liedchen ganz entzückt war. Das Quintuor hatte nach seinem Wunsche die Gliederung und Instrumentierung des damals noch neuen Hummelschen Quintettes, recte Septuors, zu erhalten. Schubert war damit bald fertig, die Sparte behielt er selbst.” Jozef Focht, Der Wiener Kontrabass, Spieltechnik und Aufführungspraxis Musik und Instrumente (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1999), 130-131.

[23] “Beim Spiel der Bassstimme auf dem modern gestimmten Kontrabass fällt der gewaltige Unterschied im technischen Schwierigkeitsgrad zwischen den überwiegend bescheidenen Anforderungen an die Applikatur in allen fünf Sätzen und den wenigen, besonders schweren Passagen auf. Dies sind im ersten Satz die Takte 181ff, sowie die vierte Variation des Forellen-Satzes. Die zuerst genannte Stelle ist in der Wiener D-Dur-Stimmung in der gewöhnlichen Lage ohne nennenswerte Lagenwechsel oder andere Schwierigkeitên ausführbar, während die Applikatur der letzteren in der Stimmung D A d fis a so vereinfacht wird, dass sie auch für einen Laien zu bewältigen ist.” Ibid, 133.