The Non-React facet is characterized by statements such as: "I perceive my feelings and emotions without having to react to them". It includes aspects such as watching negative thoughts, emotions, distressing feelings, or images and being calm before taking action or responding to a situation. Participant A experienced the biggest increase in her perception and non-reaction to feelings in a musical context. This improvement is reflected in her report when she claimed that through meditating, she could see her impatience and learn to slow down. The rest of the participants slightly improved from pre to post-intervention in the FFMQ or remained the same from pre- to post-intervention for the MfM (Participants B and C). Participant F's increase in non-react for both questionnaires is also reflected in what she expressed during her interview at the end of this statement: “By focusing on breathing during the meditation, I was more aware of it during my practice session after, especially in the moments where my breath gets stuck, and I feel less grounded/relaxed. Usually, I notice this too, without the meditation tool, but the meditation helped me with recognizing it quicker and also knowing what to do when the tension comes and when the tension comes and when my breath gets stuck” “and with reassuring myself that it’s okay when it happens.”

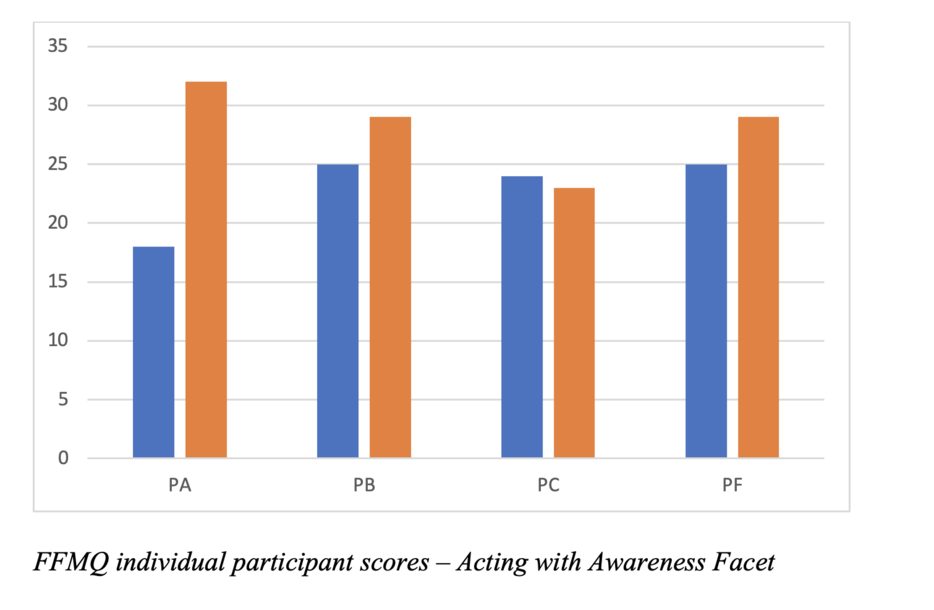

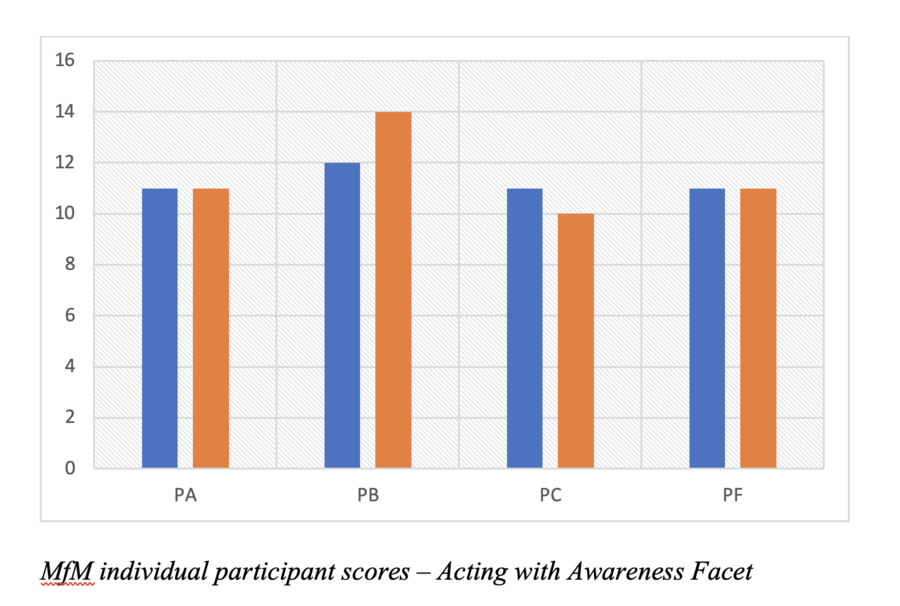

In the FFMQ, the “Act with Awareness” facet is characterized by statements such as ’When I do things, my mind wanders off and I’m easily distracted.’ It describes states of focus and attention and how they vary depending on whether we are on autopilot, wandering, or rushing through activities. In the MfM, this facet refers to awareness of distractions when practicing or during lessons. After the intervention, there was a particular increase in awareness for participants A, B, and F for the FFMQ and only in participant B for the MfM. In the interview, Participant A pinpointed the fact that the meditation had helped her be more focused and awareness of distractions during technical work (scales, warm-up, etc). Participant B stated that the standing meditation helped her specifically to refocus in the evening sessions. Participant F mentioned that doing the meditations was hard when being “busy on your mind” but that by making the effort, meditations had helped her “be better focused on 1 thing more easily”. Having participants do the meditations in such a busy time (before their mid-term exams) made them realized they were usually impatient towards practicing.

Mind-wandering

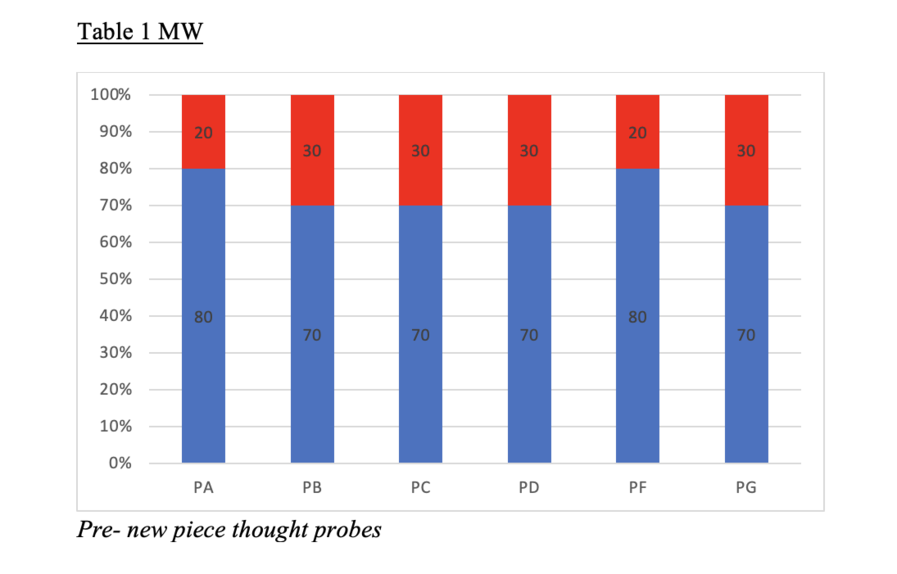

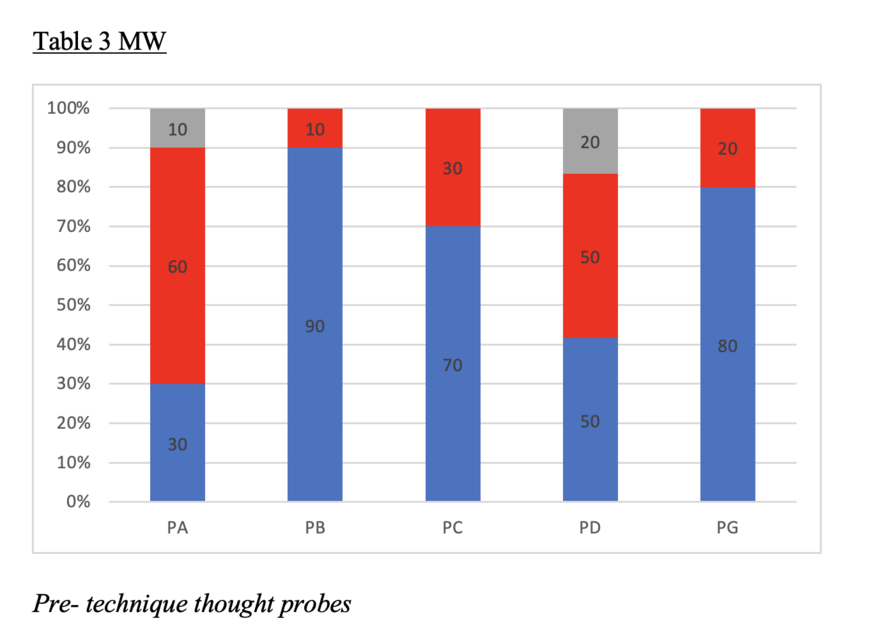

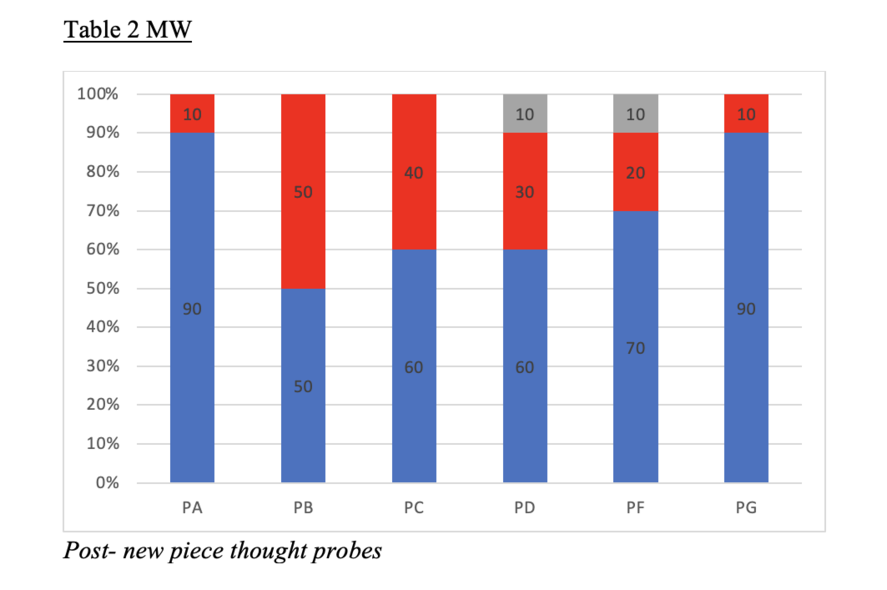

Participants (A, B, C, D, F, G) completed the mind-wandering thought probes and follow-up questionnaires before and after the experiment.

Note: if participants were taking a break (drinking water, looking at the phone, etc. ) and the alarm notified them, that moment was counted as a distraction since this category is considered as neither being focused nor being wandering while on task. Descriptive statistics were used instead of inferential due to the small sample size.

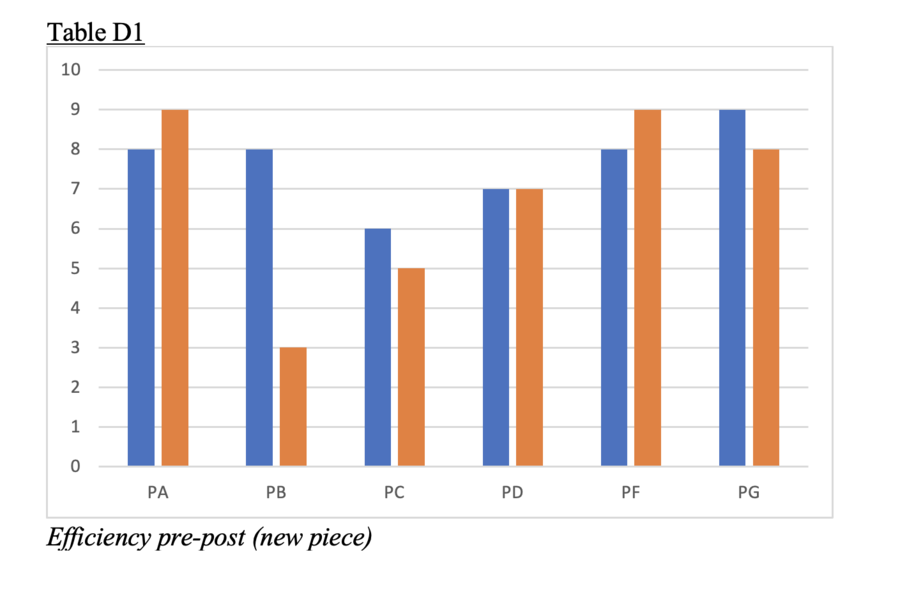

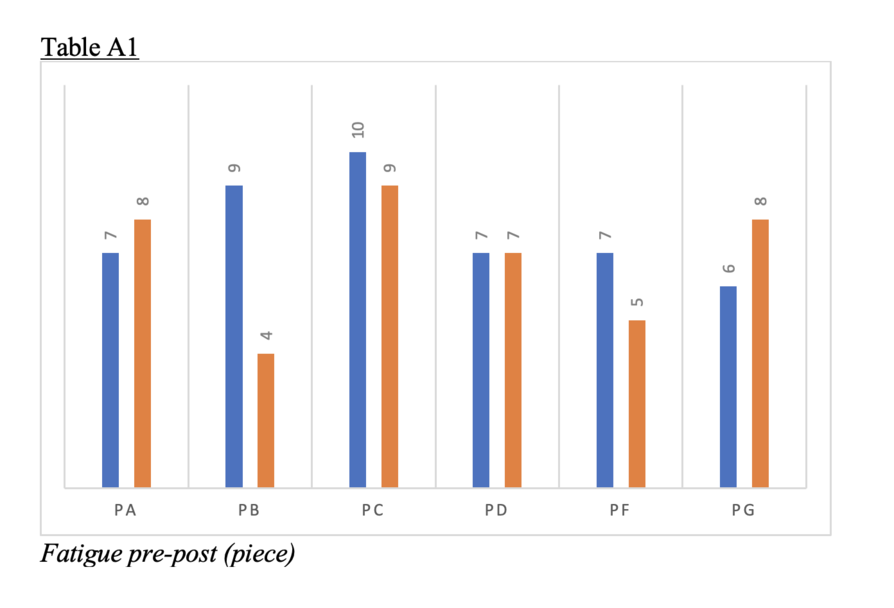

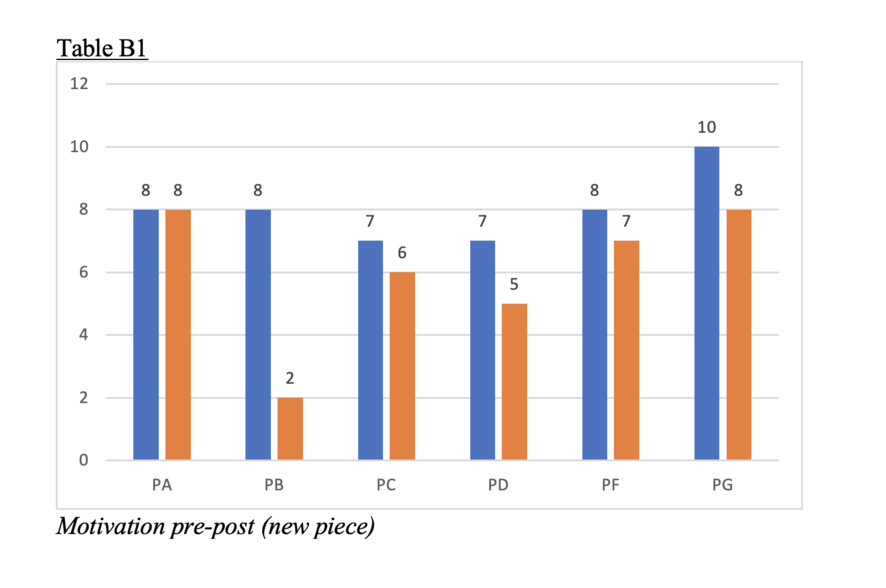

New piece

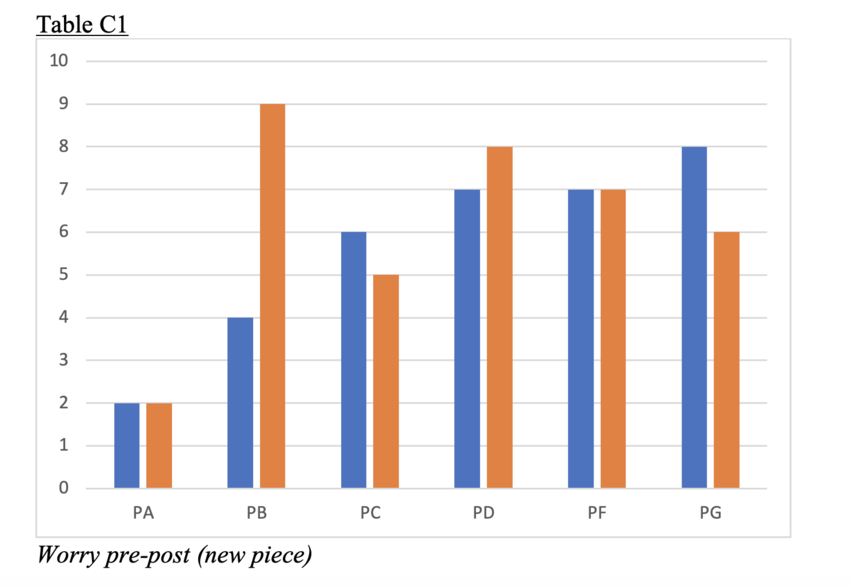

Regarding the new piece, we observe improvements in terms of attention in participants A and G from pre- to post-test. That is, these two violinists caught themselves more times focused than distracted when notified by the random alarm. On the other hand, we also observe an increase in mind-wandering rates in Participants B and C. This may be due to insufficient meditation time to achieve more resilience to distraction, but also due to a very noticeable increase in fatigue (Table A1) worry (Table C1), and a decrease in motivation (Table B1). In the interview, participant B commented having been sick during indicated when carrying out the post-experiment questionnaires. In the case of Participant D, we observe high levels of worry (Table C1), and moderate motivation, but the only difference we observe from pre- to post-thought probes is an outside distraction (o.d) (Table 2 MW) (i.e. “taking the phone because he was feeling tired”)

Mindfulness

At the end of the meditation week, only participants B, C, and G did all seven meditation sessions. Participants A and D did five of them and participant F did 4 of them. Out of the six participants, four participants (A, B, C, F) completed the FFMQ at the beginning and end of the meditation week. This measure was used to identify mindfulness trends as a result of the intervention study. Notably, one week of meditation may not yield great changes in musicians’ behavioral patterns; however, results may elicit slight positive changes that could potentially be enhanced with more mindfulness practice.

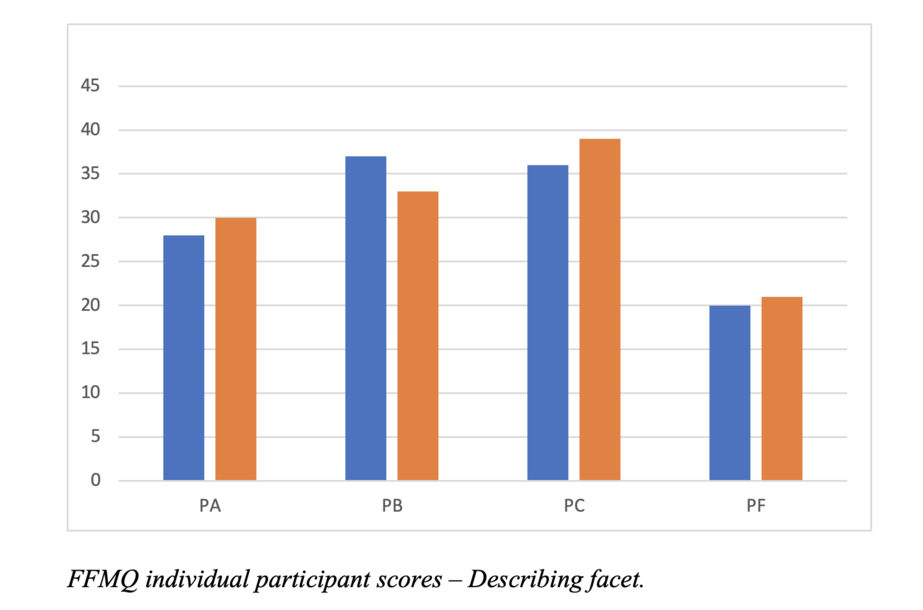

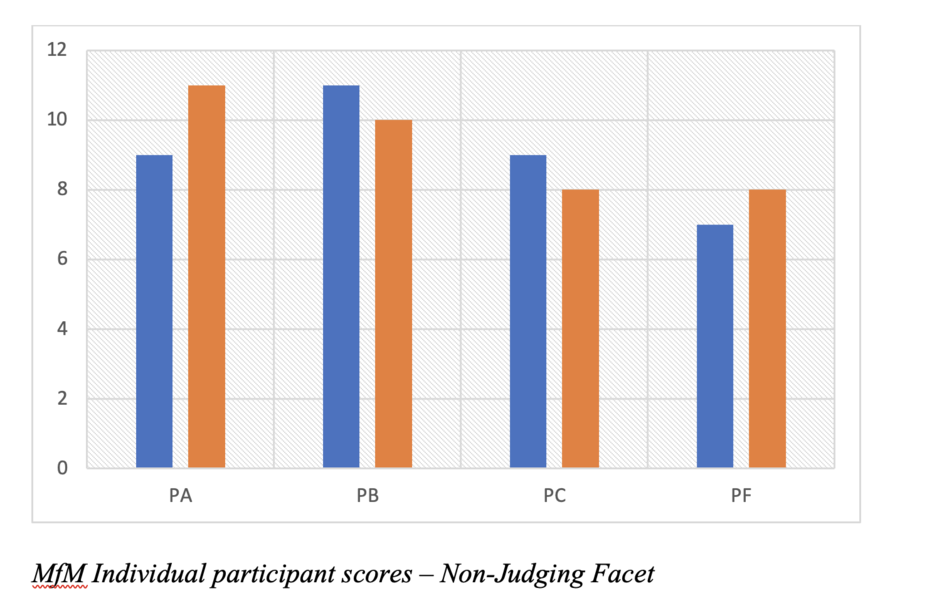

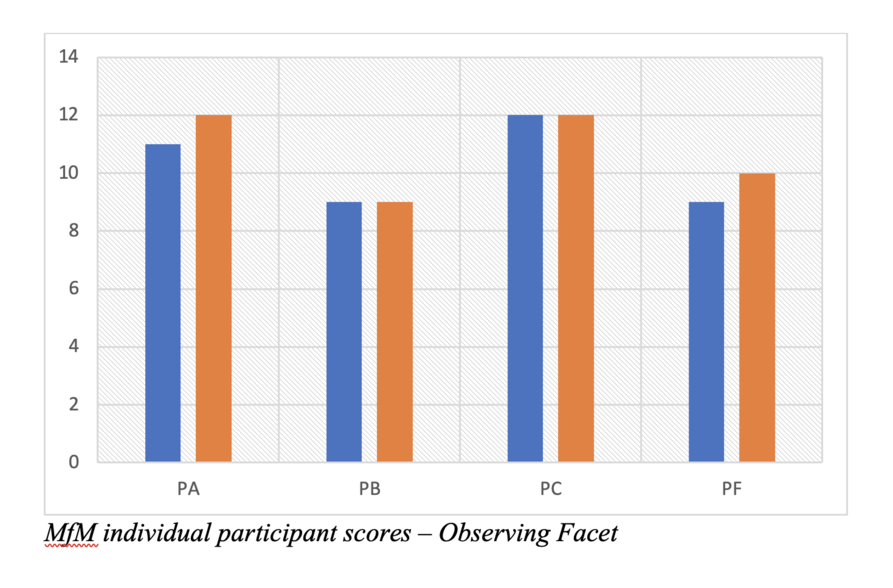

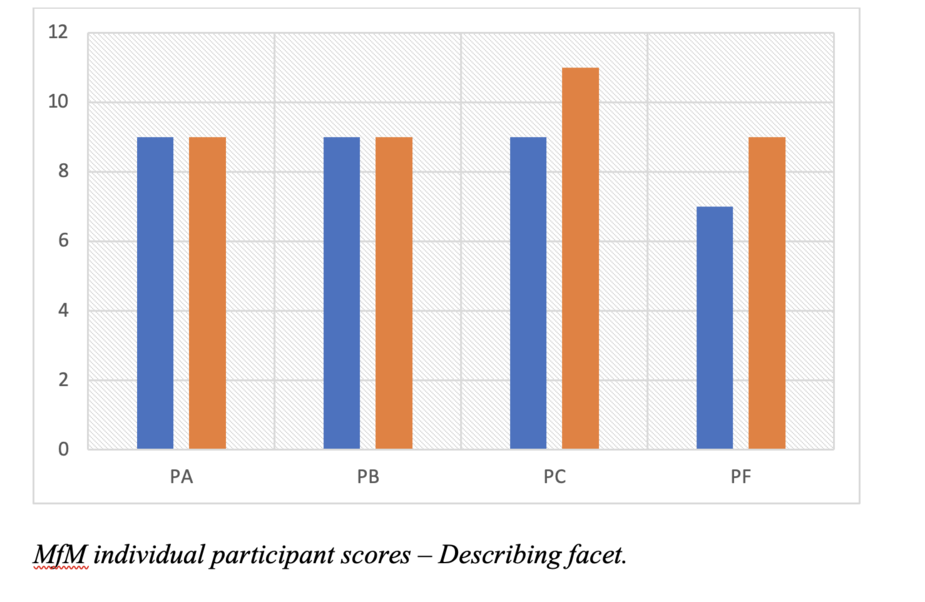

Table 1 shows the pre- and post-mean scores for the five facets for all participants combined. Data show an increase for all five mindfulness facets, particularly noticeable for the “Acting with Awareness” and “Non-Judge” facets.

The same four participants also completed the MfM at the beginning and end of the intervention. This measure was used to elucidate possible changes in participants’ levels of mindfulness in the music field. Table 2 shows the pre- and post-mean scores for the five facets for all participants combined. Data show slight increases for all facets, but most noticeably for the facet “Describe”. Descriptive rather than inferential statistics were used due to the small sample size. Thus, each participant’s data is examined without formulating hypotheses of how these results would apply to a larger population.

Technique

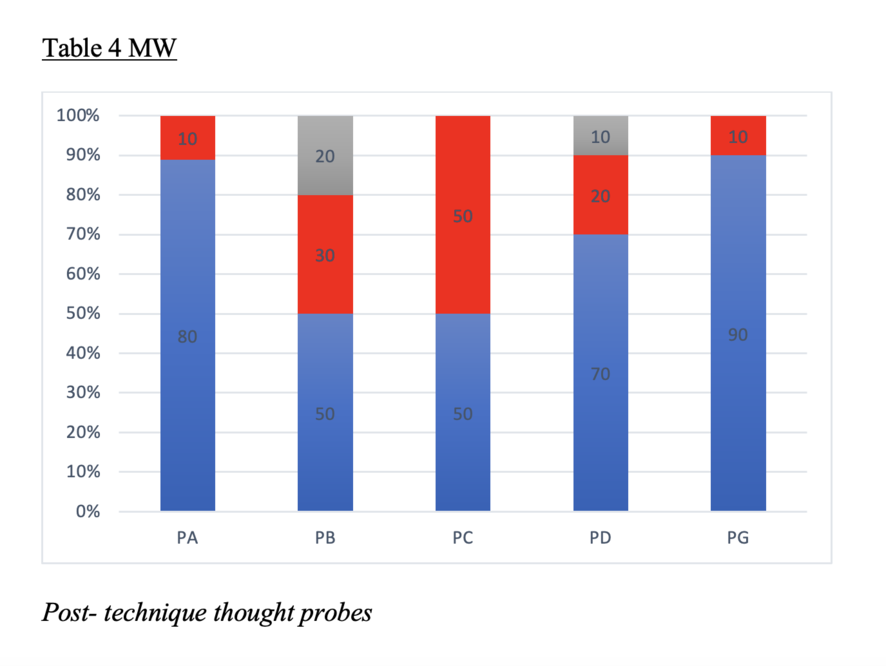

Regarding the thought probes during technique practice (Table 3MW and Table 4MW) we can observe that participants tended to ruminate or get distracted more easily than when practicing new pieces. According to the literature when carrying out motor tasks that have already been proceduralized and are implicit and automatic in the individual, these would not require so much focus or cognitive effort, and therefore musicians, in this case, would be more likely to drift away or to fall into rumination (Kane et al., 2007, Levinson et al., 2012; Stawarczyk et al., 2014).

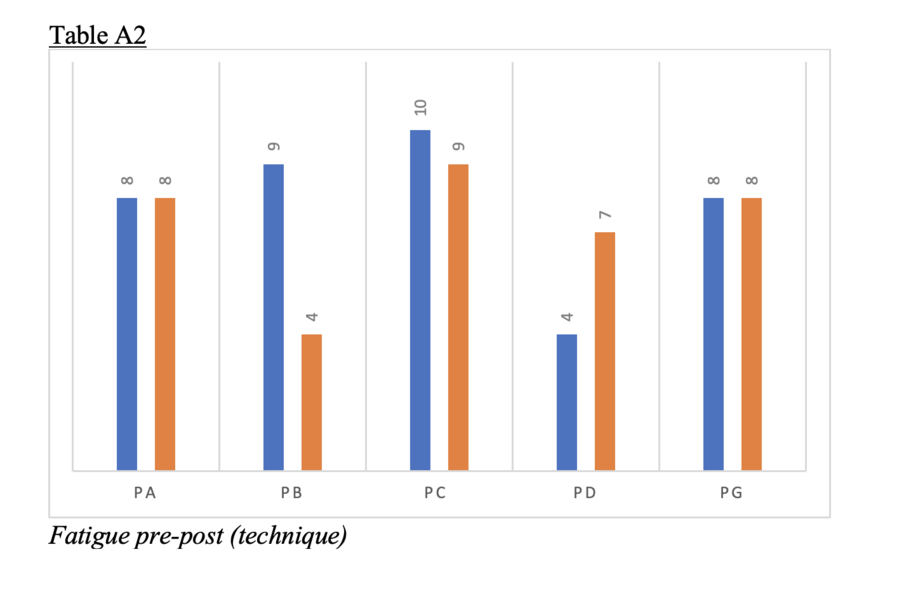

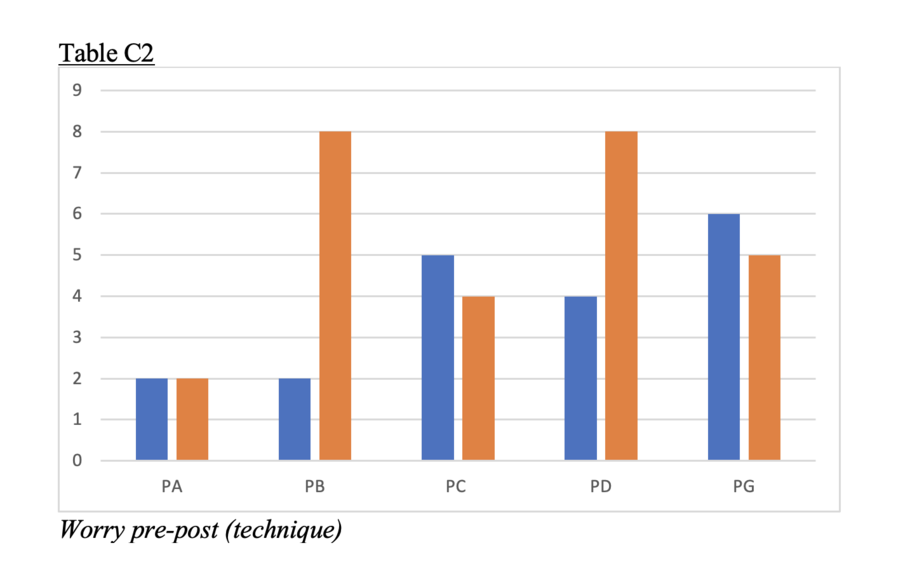

From the beginning to the end of the intervention, Participants A, D, and G improved their focus or became less distracted while practicing their technical work. On the other hand, Participants B and C showed more distractibility after the intervention. These two drops in attention could be due to, again, contextual variables contained in data contained in the follow-up questionnaires regarding motivation, fatigue, and worry levels. In the post-intervention (Table 4MW), Participant B was tired, worried, and not motivated. Participant C was also only moderately motivated and worried. These have been demonstrated to be influential contextual reasons for the occurrence of mind-wandering (Robinson et al., 2020).

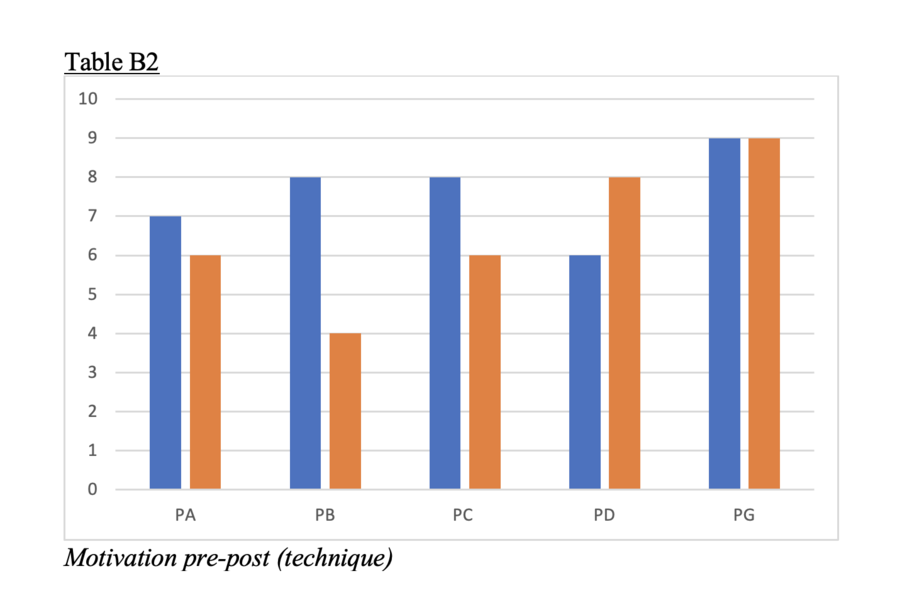

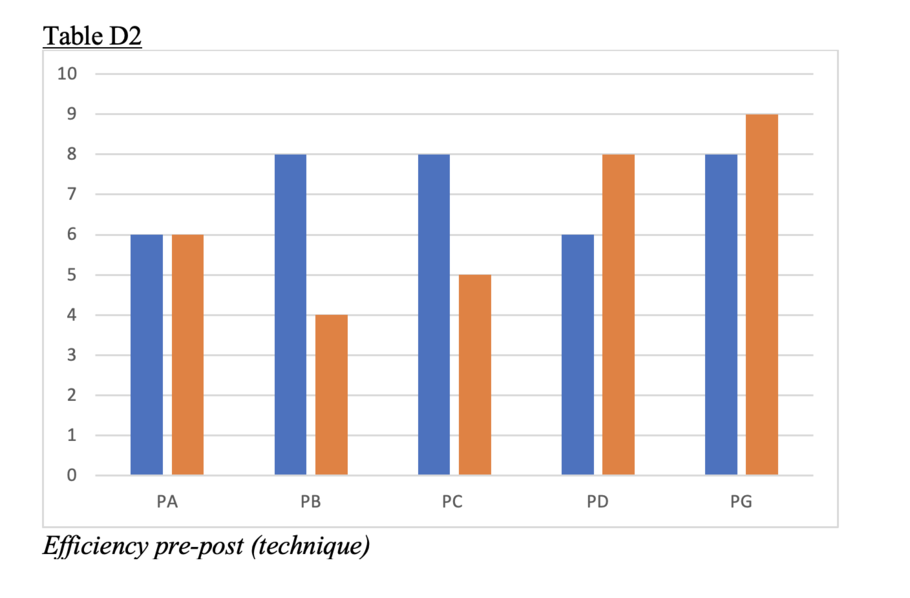

From the above results, what is most striking in terms of ostensible benefits of the meditation in participants’ levels of mind-wandering is participants’ A, D, and G improvement in focus during technical work from pre- to post-intervention. However, these improvements could also have been partly or entirely due to changes in motivation, fatigue, or worry. For instance, in participant D, such improvement might have been caused by improvement in sleep (from 4 to 7, out of 10 pts.) (Table A2) or motivation (Table B2). However, Participant D's levels of worry in the post-test were very high, which would have led to more rumination (Table C2). Thus, it seems that his motivation and good sleep may have been strong enough for this participant to overcome his worry. Concerning Participant A improvement in focus from pre to post-test, we cannot attribute it to contextual variables since they remained, with exception of motivation dropped by 1 point, stable. Therefore, it is possible that meditation could have helped this participant be more focused, regardless of contextual variables. Participant G's improvements, though less significant than A or D, improved her focus from pre to post-test. In this case, she showed a decrease in worry (C2), which may have been caused by the meditation, while the other two contextual variables remained stable. Thus, it seems that she could have benefited from the mindfulness meditation week. Regarding participants’ changes in efficiency (Table D2), these 3 participants either remained stable (A) or improved substantially (D and G).

On the other hand, besides the small sample size and lack of correlational coefficients, we cannot conclude that mindfulness positively made a positive or significant impact on all participants’ levels of mind-wandering. These could be due to many reasons, but there are two that might be of the most importance. First, the short amount of meditation time may have prevented participants from developing an improved ability to come back more frequently and quicker from distractions to the present. Second, contextual variables such as lack of motivation, lack of sleep, or excess of worry may have turned participants more distracted.

Table 1 Pre- and Post-FFMQ mean scores for all participants.

|

Mindfulness Facet |

Post -Mean (SD) |

|

|

Observe |

23.75 (4.19) |

24.75 (5.37) |

|

Describe |

30.25 (7.93) |

30.75 (7.5) |

|

Acting with Awareness |

23 (3.37) |

28.25 (3.77) |

|

Non-Judge |

26.25 (5.56) |

30.5 (4.51) |

|

Non-react |

18.25 (3.86) |

19 (3.65) |

Table 2 Pre- and Post- MfM mean scores for all participants.

|

Mindfulness Facet |

Pre-Mean (SD) |

Post -Mean (SD) |

|

Observe |

10.25 (1.5) |

10.75 (1.5) |

|

Describe |

8.5 (1) |

9.5 (1) |

|

Acting with Awareness |

11.25 (0.5) |

11.5 (1.73) |

|

Non-Judge |

9 (1.63) |

9.25 (1.5) |

|

Non-react |

8.25 (1.26) |

9 (0.82) |

Both questionnaires’ facets will be analyzed in parallel. That is, the “Observe” facet from the FFMQ will be examined along with the “Observe” facet from the MfM, the FFMQ “Describe” with the MfM “Describe”, etc. This way, we can describe trends regarding general trait mindfulness (FFMQ) followed by trends that refer to participants’ mindfulness during musical activities (MfM). Moreover, results from these two questionnaires will be contrasted with participants’ subjective reports in the interviews at the end of the intervention.

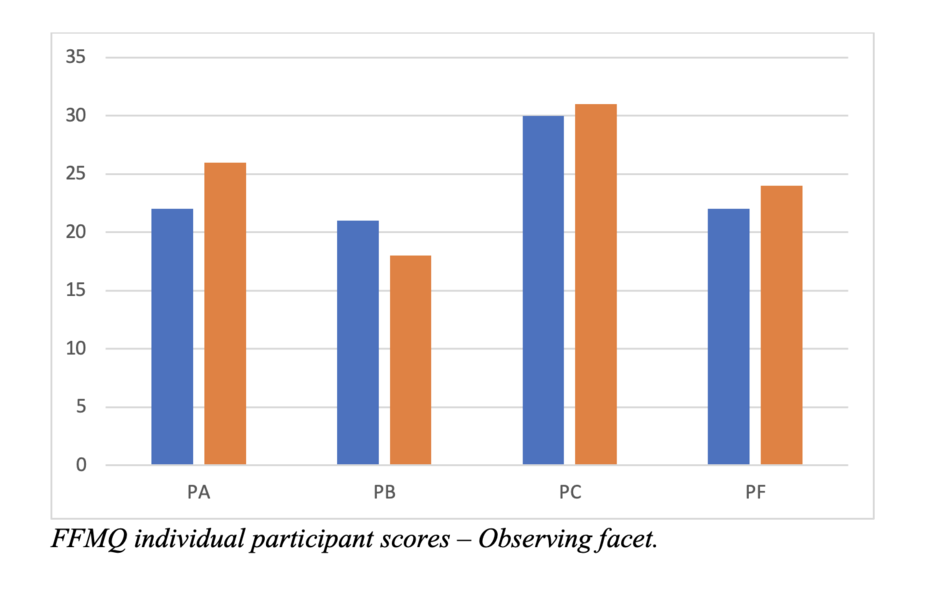

The Observe facet in the FFMQ is characterized by statements such as ‘When I’m walking, I deliberately notice the sensations of my body moving.’ It covers the awareness of information picked up by the senses from the participant’s surroundings and the effect they have on the body or mind. In the MfM it refers to the physical sensations or sounds when playing as well as muscular or slight changes of sound. Participants A, C, and F improved in this facet in the FFMQ and only A and F did in the MfM.

Participant A recognized an increased awareness in the perception of gravity at the beginning of the practice session after meditating: "When I meditated I felt more the body gravity". She was also able to identify changes in her breathing more easily: "Normally, I am not so aware of my breath". Participants C and F also recognized more awareness of their breathing.

“By focussing on breathing during the meditation, I was more aware of it during my practice session after”, “, especially of the moments where my breath gets stuck and I feel less relaxed". "Usually, I notice this too without the meditation tool, but this helped me with identifying it quicker and also knowing what to do when the tension comes and when my breath gets stuck.”.

Participant F also emphasized how the meditation helped her become more aware of her body tension during rehearsal. The three participants admitted that these changes in observation happened especially at the beginning of their violin practice and then they faded away as they continued practicing during the day. Participant B's score decreased slightly on this facet in the FFQM, however, during the interview, she mentioned liking the integration of the instrument in the meditations and applying the acquired sensations during the meditation into a piece later in the practice.

In the FFMQ and MfM, the Describe facet is characterized by statements such as ‘I’m good at finding words to describe my feelings.’ It covers the ability to describe beliefs, emotions, opinions, sensations, and experiences clearly. Participant A commented that meditating gave her the chance to detect moments of impatience and distracting thoughts. In the interview, she also mentioned that after meditating she noticed she was more serene. Participant C felt that through meditating she could detect thoughts and disengage from her internal dialogue easier. Participant F recognized becoming more aware of her mental state during practice. Participant B, though with lower (FFQM) or sustained levels in the Describe facet, claimed that thanks to the meditation, she was able to have a fresher mindset during the evening, when she recognized feeling more tired.

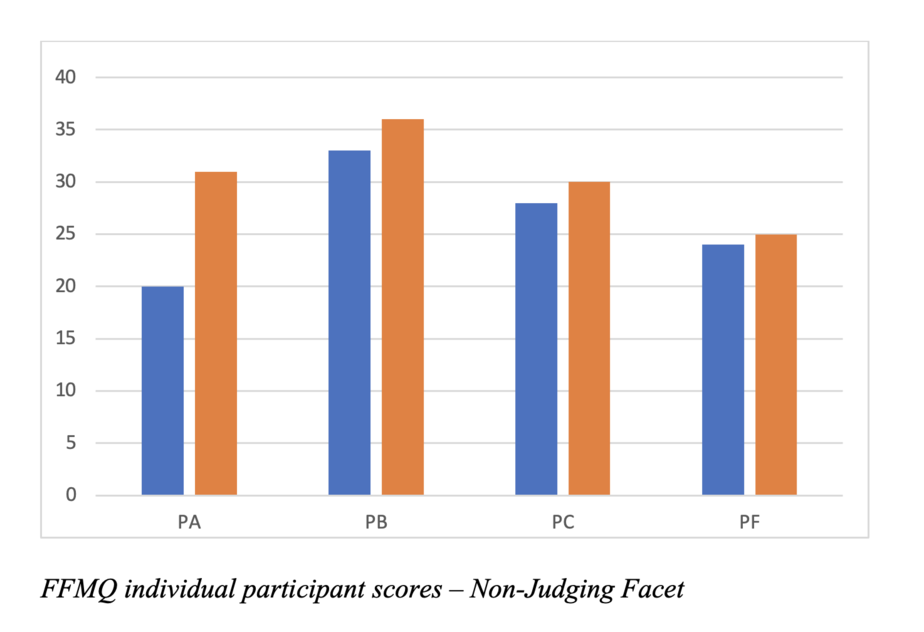

The Non-Judge facet is characterized by statements such as ’I criticize myself for having irrational or inappropriate emotions.’ It covers aspects of self-judgment when emotions or thoughts are perceived as good or bad followed by mental self-punishment. All participants seemed to improve in this facet of the FFMQ. However, participants B and C slightly decreased in this facet for the MfM, which contradicts the FFMQ. These colliding results might come from an insufficient amount of meditation time, which may be necessary to change how musicians judge themselves.

Interviews

Even though much of the interview content has already been contrasted with the quantitative data, Participant D and G’s feedback was left out of it since they had not completed the mindfulness post-questionnaire. In addition, some interesting feedback from the ones who did complete the questionnaires that could not fit in the quantitative data will also be examined.

After the meditations Participant D found his awareness of thoughts during practice particularly benefited from the meditations. He admitted that he now felt more aware of his distracting thoughts and the “avalanche of thoughts” that wanted to “enter his consciousness”. Like other participants, he was calmer and focused right after finishing meditating. Regarding Participant G, she stated feeling “felt very relaxed when I started practicing” right after meditating. She also felt that meditation had helped her to improve her concentration and awareness of the body: “it felt easier to get into a certain focus”. She also progressively became more aware of “some bad physical habits” and more compassionate towards physical discomfort and how to correct it (e.g., she tried to find ways to improve in a physical aspect without irritation and with more patience). During lessons, she even felt more grounded and aware of her body.

The rest of the participants acknowledged having noticed some benefits of the meditations by helping them become more aware of the importance of “dedicating time to being calm” (Participants A, F, and G), or of how they behaved and reacted to different situations during practice (Participants A and F). More specifically, Participants, C and F recognized the value of doing the breathing meditation: “In general, I think the exercise about connecting the breathing with playing can be really helpful for any musician”, and “it can be good for me to use this exercise more often, whenever I feel like I’m not calm enough and I notice it affects my sound” (Participant F); “I am now applying the breathing meditation to my practice, it is especially helpful when doing bow changes” (Participant C). The last statement supports the idea that mindfulness meditation could potentially benefit instrumental performance (Czajowski, 2021; Hribar, 2012; Juncos et al., 2017). Furthermore, some participants also recognized the value of meditating as a tool to plan their days better and more recenter (Participant F) which corroborates results obtained by Czjakowski & Greasley (2015), where participants became more structured.

Several participants felt that the effects of the meditation lasted longer at the beginning of the session but then fade away as they continued practicing (Participants A, C, D, and F). This could call for the implementation of a more consistent practice of mindfulness in musicians’ routines for they to fully experience the benefits of meditating in the long run. Some participants expressed a desire to keep meditating on a more regular basis: “it can be good for me to use this exercise more often” (Participant F); “Meditating helped me when recognizing my mental patterns, but I would need more time to let it change them”, “I am considering continuing the meditations” (Participant A); “it may be able to benefit me in the long run” (Participant D); “I would do it again, it helped me” (Participant G).

Finally, participants also expressed their opinion about the designed mindfulness recordings. Overall, the feedback from the meditations was positive, receiving good input from all participants: “the recording was nice to listen to” (Participant C); “It was calming”, “it felt good” (Participant B); it was a “calming voice” (Participant G).