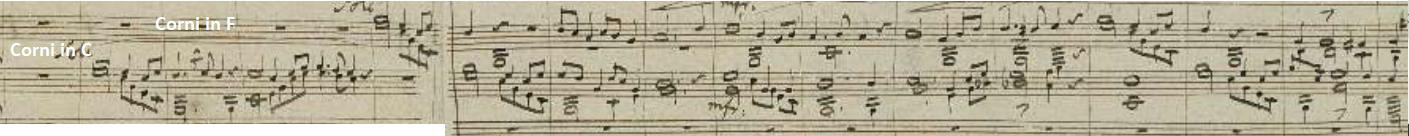

It was rare in the classical era that the composers used more than two horns in their composition. Of course, there are examples, like the ‘Hornsignal’ Symphony by Joseph Haydn, or Beethoven’s ‘Eroica’ Symphony. In this case, there were mainly two options for how the composer used the horn section(s). Whether they put all of them in the same key and used them both as one big section, for example, for solis, or the two pairs changed each other; or there were two pairs of differently crooked horns. In this example, they played mostly in different moments, which made it possible that the instrument was present through the entire piece. At the turning point between the classicism and romanticism, it became more regular to use four horns, especially in opera music, like in the Freischütz from Carl Maria von Weber. The two earlier methods were still used, but the composers started to use the two pairs more often together at the same time, even though they were differently crooked. One example is the already mentioned place from the 1st Symphony of Schumann, but I could show the most famous excerpt in this writing style, the beginning of the Overture to the Freischütz. Weber mixed perfectly the two differently pitched horn pairs. In measure 16, it sounds like a typical horn fifth passage between the first and second horn, but it is impossible, because the lower voice would be inaudible on the F-crook. So, Weber also solved the problem in another way. The first horn plays the upper voice, and the third horn, which is tuned a fourth lower, takes over the second voice. Also, the chords can be built up perfectly if one of the horns plays the third, which has to stop for that note. The end of the same excerpt is like this. The first horn in C plays the melody in the last three bars, while in the last two chords, first the first, then the second horn in F has the third of the chord. Both of them have to be played stopped on the F-crook, therefore it makes a perfect balance, that the third that should always be the quietest one in a chord is naturally a soft and hidden note.

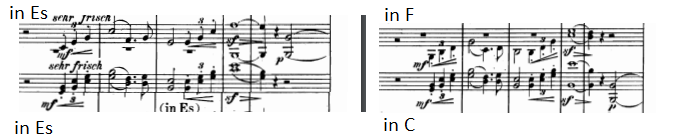

We can also see that he asks the valve horns to change the crook. As Henri Kling, and Oscar Franz said too, it is possible to hide the difference between the crooks with a couple of half notes difference, but it is noticeable if the difference is a fourth or even bigger. Therefore I would recommend choosing more carefully between the F and Bb horn. Since the horn players used the Eb,E, and F crooks the most on the valve horn in this time, it was exceptional, if the composer asked for the C, or even for the D crook. In my opinion, we should make a difference too. Of course, it is possible to play with more open mouth, or give faster or slower air, but this makes this change also easier. If one plays the the two solis from the Genoveva Overture, only because of the different tonality there will be a difference between the two excerpts, but if we take the shorter Bb horn for the first one, and the longer F horn for the second one, than also the feeling for us, but also the result will be much more audible, and more interesting. The composer also wanted to hear a difference, otherwise he could have just taken the open valve horns and let everything play on the same crook.

The frequent tonality changing became also a standard task of the natural horn players. In classicism or even in the French romanticism the horns usually changed the tonality in the new movement or maximum two times in one movement, one of these changes is usually the returning to the original tonality. If we want to say the average number of tonalities in a normal symphony, then three different ones is the maximum, and no more than two in one movement. When the composers used valve horns too, these numbers increased. For instance, only in the overture of the Genoveva opera, the natural horns play in C basso, Eb, Bb basso, and then in C basso again.

To be in the same tonality and have an open sound was not the only reason why Schumann let transpose a lot of the natural horns. As we know, the different tuned horns also have slightly different sound, and different character. The high horns have a brighter and shinier sound, in contrast, the low horns have a rounder, warmer, and darker sound. The classical composers made use of this diversity, and also the romantic composers did so. Like in the second movement of the Rheinisch Symphony, the horns in C are playing the echo; or we can make a parallel between the waves of the Rhein and the horns, the first wave/horn is more visible, and there is always the next, but it melts into the one before it.

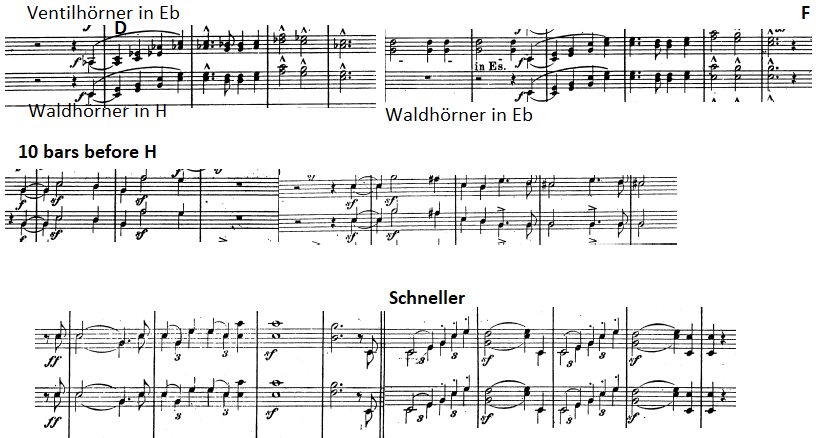

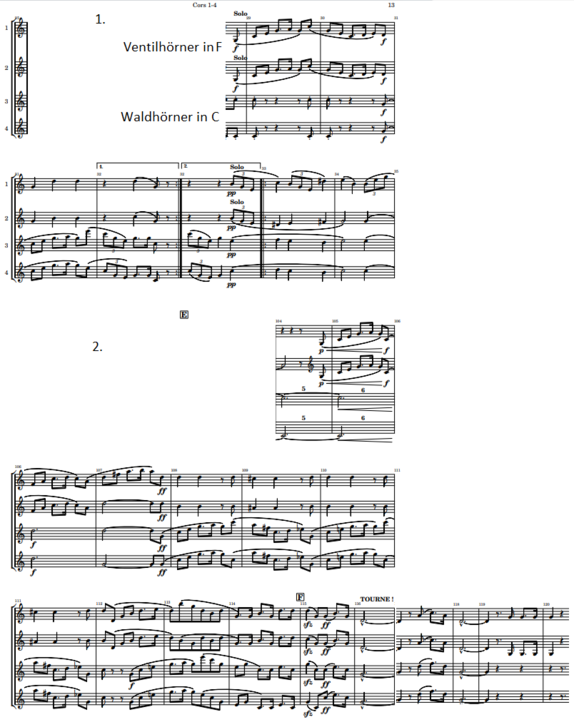

But how did this and any other similar connection within the horn group with the existence of the valve horn? With the valves it became possible to provide an open, and healthy sound all the time, but the natural horns were there in case of the need of any special character or sound colour. The mentioned excerpts in the fourth movement of the fourth symphony, or the beginning of the fourth movement in the Rheinisch Symphony were written in this way. Here Schumann tried to blend the melodic and warm sound of the valve horn, and the also warm, but brassy and very vibrating sound of the natural horn. Schumann was looking for this sound a lot of times in the 3rd Symphony:

-

At letter A & L in the first movement

-

At letter D, 4 bars before F, 10 bars before H & 4 bars before Schneller in the last movement.

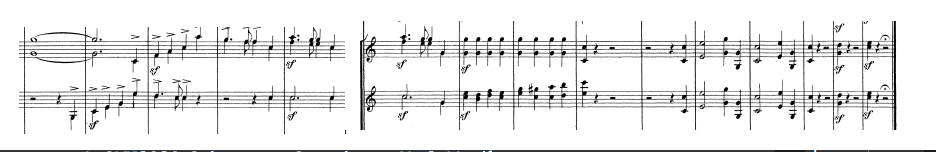

And the last interesting use of the horn section is that the first horn ‘loses’ its first place in the excerpts like the mentioned ones from Genoveva, at the end of the 3rd Symphony. Instead the first horn, the third horn, or first Waldhorn takes over the high passage. Why is it so? Because the natural horn is more flexible in the high register, and it is easier to play these passages on this instrument, since these are excerpts, which are close to the original natural horn passages. The instrument, as I explained too, is lighter than the valve horn and therefore it is easier to play these quick, and loud sections more efficiently and easier.