Jon Hendricks: Pioneering Jazz Singer, Scat Innovator, and Master Lyricist

Written by: Carolina Peña

1. Background

Early Life

Hendricks was born on September 16th, 1921, in Newark, Ohio, and grew up in a big family of 14 children. Within his family lineage, he was the son of Reverend and Mrs. Willie Hendricks. His father was a Minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and his mother was a singer and lyricist. She used to write lyrics to some spirituals for the church. With that being said, Hendricks develops himself within music and lyrics, with a profound approach to church and spirituality. He began singing at the age of 8, at family parties and dinners. Later on, he sang for pennies, nickels and dimes [1] outside cafes, bars and restaurants. In his last interview with Jazz At The Lincoln Center, Hendricks mentioned that he used to memorize all the songs from the Jukebox. [2] Therefore, before the customers inserted their nickels, he offered to sing the song they wanted for some money. He did this to help his family financially because his parents had to take care of a large number of siblings. He developed in Toledo, within a small distance of the great jazz piano player, Art Tatum. Eventually, Tatum becomes his mentor and teaches him, at age eleven, how to arpeggiate chords, chord changes, the sonority of jazz chords, and two-five-one’s. This was essential for his ear development. It’s important to mention that Jon Hendricks was a musician that relied mostly on his ear, as he did not know how to read music, he still became one of the biggest and greatest jazz singers of all time.

By the age of fourteen, he was opening acts for Louis Armostrong, Duke Ellington, Fats Waller and Count Basie. Subsequently, he was discovered by Charlie Parker in a concert in Ohio, when Parker told Hendricks he should go to New York and “join the music business.” [3] As advised, he flies and gets based in New York City in 1952.

2. Work and Development

Jon Hendricks starts working as a songwriter and singer in New York City. He used to sell lyrics for composers and musicians, such as Louis Jordan, Louis Armstrong and King Pleasure. The songwriter “corner” was on 52nd and Broadway, and Hendricks mentioned this place as an integrated racial community, where he worked alongside Quincy Jones as well. In this work atmosphere he meets Dave Lambert, singer and musician, who becomes his working partner and peer friend for the years to come. Alongside Lambert, they start writing arrangements and compose lyrics for Count Basie music. The process for the music was to transcribe the horn instrumental parts, make an arrangement and add lyrics to it that had musicality, and storytelling sense. This was later recognized as a vocalese.

Defining Vocalese

Vocalese it’s considered as a subgenre in jazz, and it emerged in 1927 with Bee Palmer’s rendition to Bix Beiderbecke’s “Singin’ the Blues" [4] It was in the 1950s that was officially defined as Vocalese, by Jazz critic Leonard Feather when reviewing Annie Ross, “Twisted”. The term “vocalese” suggests a multi-layered meaning that involves language, voice, and instrument. While the voice provides language through lyrics in the conventional sense, it also transforms into an instrument by performing full instrumental melodies and improvisations. In essence, the voice assumes a dual role as both a language provider and a musical instrument.

Lambert, Hendricks & Ross

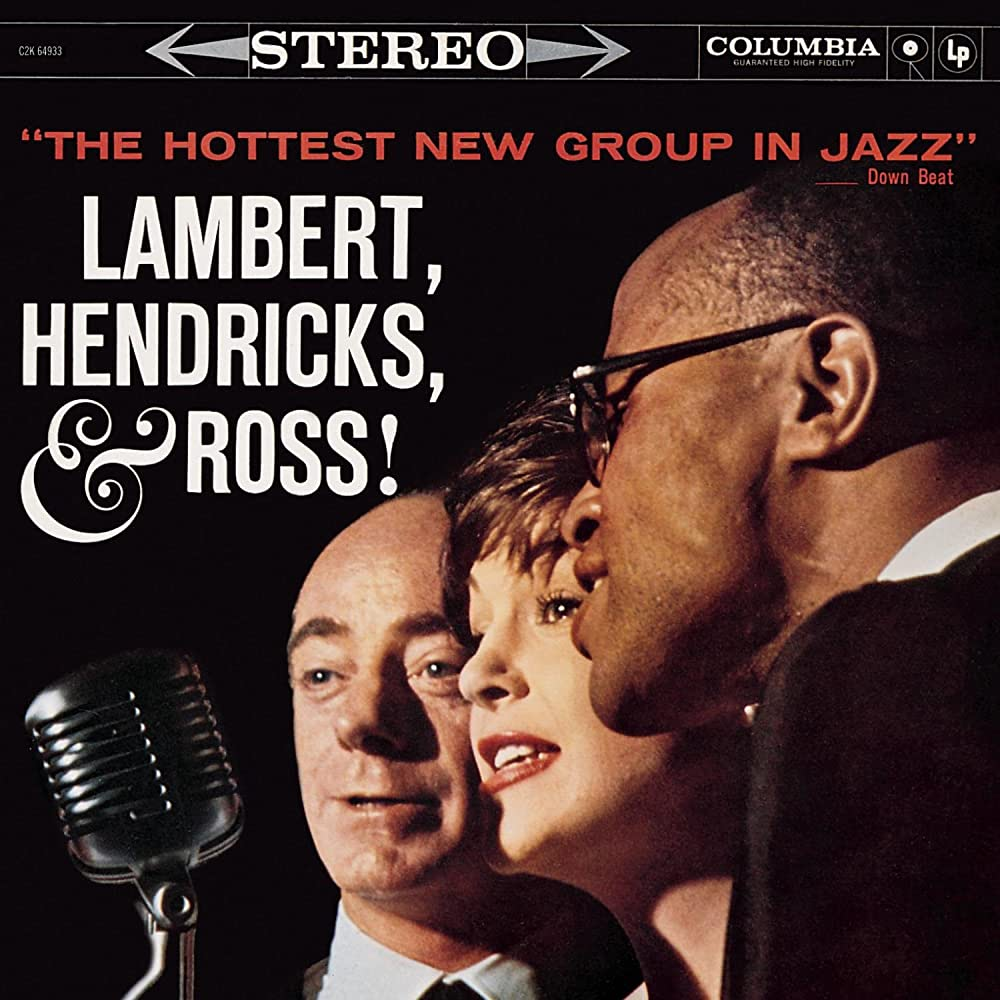

His collaboration with Dave Lambert began in 1957. The duo recorded “Four Brothers” which led them to the association with singer and writer, Annie Ross. The trio continued writing arrangements to multiple Basie songs. By 1958, under the name of Lambert, Hendricks & Ross,they released their first hit album “Sing a Song of Basie”. Their success was strategic, arranging music by Basie that people knew and loved, the group found the way to capture attention on an already established audience base. With the addition of lyrics to the horn parts of the big band’s arrangements, they maintain a connection to the legacy of instrumental music.[5]

The album included songs such as “Everyday”, “One O’Clock Jump” and “Four Brothers”. Lambert, Hendricks & Ross became one of the most popular vocal groups in jazz. Furthermore, the group’s success caught the attention of Count Basie, who featured them on his album “Sing Along With Basie” in 1958. This led to a tour with Basie’s big band, cementing Lambert, Hendricks & Ross’ reputation in the jazz world.

Consequently, the group published vocal arrangements for Charlie Parker’s “Now’s Time”, John’s Coltrane’s “Mr. P.C.”, and Miles Davis “Four”, among several more jazz individuals. With Lambert as the arranger and Hendricks as the lyricist, the trio became masters of vocalese and traveled the world, earning numerous awards and praise. In September of 1959, they were featured on the cover of Down Beat Magazine under the title “The Hottest New Group in Jazz,” which they later used as the name of their Grammy-nominated fourth album. [^6}

Influence

Hendricks had a unique approach to songwriting, where he wrote lyrics not just for melodies, but also for entire instrumental solos. For example, his version of Ben Webster’s tenor saxophone solo on Duke Ellington’s original recording of “Cotton Tail” was featured on the album “Lambert, Hendricks and Ross Sing Ellington” in 1960. His lyrics for Benny Golson’s “I Remember Clifford” have been recorded by several other vocalists, such as Dinah Washington, Carmen McRae, Nancy Wilson, Ray Charles, The Manhattan Transfer, and Helen Merrill. [6] His vocalese solo for “Don’t Get Scared” by Stan Getz, was recorded on Kurt Elling’s live album, “Live at The Green Mills”. Aswell, Jazzmeia Horn mentions in an interview with Jazz at the Lincoln Center, that the “Don’t Get Scared” recording moved her deeply and make her comprehend the profound significance of transcription and vocalese. This experience eventually led her to become a mentee of Hendricks.

Scat Innovator

Understanding the impactfulness of language and knowledge within Hendricks, his life career was a success. Along with his discography, and world tours, he also influenced the world of jazz, especially vocal jazz. His genius created a new platform, vision, and field for upcoming jazz vocalists and his contemporaries. Hendricks mastered his improvisational skills in the ability of scatting syllables within an extraordinary mimic, lines, and harmony understanding within his solos. It’s very clear that within his work of transcription, the language and style is precise. Some recordings such as “Mr. P.C”, delivers a scat improvisation that refers to Coltranes style and lines, as well in his rhythm changes solo, “Listen to Monk”, bebop language it’s present and the movement within the changes it’s brilliant and virtuoso. Another great example is his solo in “Moanin” recorded with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, in Buhaina, 1973.

The next hyperlink is the transcription of this solo. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1v_pSgxDj__jICZgtjKduMDSw88d30UMw/view?usp=sharing

3. Legacy

Vocalese both draws on traditions and creates new forms of musical meaning. By singing iconic instrumental jazz repertoire with lyrics, Hendricks revises tradition. On one hand, it adheres to the musical tradition by aiming to replicate the sounds of existing recordings. However, it also challenges tradition by taking instrumental sounds and incorporating them into the voice while introducing new meanings through lyrics.

It’s important to mention that by crafting lyrics to his beloved music, Hendrick’s aligns himself with the instrumentalists who he considers important and foundational to the idiom. [7] In doing so, Hendricks partakes in the timeless practice of recreating history through the art of storytelling, preserving the legacies of American cultural icons in the world of jazz.

As an illustration, he preserves history with lyrics that highlight the existing lines between musicians and influences. In Lester Young’s “Let Me See”, Hendricks sings about Bird, and the other way round. He pays tribute to the music he believes is an essential part of American cultural legacy. Through the art of writing lyrics to instrumental solos and melodies, Hendricks not only preserves the musical essence but he also adds lineage by directly singing names of particular jazz musicians in the music.

Late Development

In terms of development of sound, or music evolution, Hendricks stayed true to tradition, Be-pop, vocalese, without a major development in style. His development is admired in the mastering of lyrics, scat performance, time feel, language and vocal technique. Taking an early recording such as “Four Brother’s” lyrics, we encounter a young aspiring and talented song lyricist. Later on, Gigi Gryce’s “Social Call” , Hendricks lyrics gained immense popularity and have been recorded by numerous jazz vocalists, such as Betty Carter, Benny Bennack III, and Veronica Swift. Ultimately, his late development is admired with his take on Miles Davis “Freddie The Freeloader” featuring Bobby McFerrin, George Benson, and Al Jarreau. He recorded a total of 14 albums under his solo artist name: Jon Hendricks.

4. Conclusion

Language as a learning tool

Hendricks had a remarkable talent for language that allowed him to connect with both instrumentalists and audiences. His lyrics serve as a bridge between music and language, as well as between voice and instrument. By closely aligning his lyrics with the music, he creates a learning tool for listeners and aspiring singers, making instrumental jazz more accessible through the common thread of language. His virtuosity lies not only in coming up with perfect lyrics, but also in how beautifully they fit with the music, enhancing the listener’s experience and helping them transcribe the music in their minds.

In addition to integrating his voice through poetry, Hendricks’ lyrics have also become learning tools for young jazz singers looking to develop their instrumental vocabulary. Lyrics help singers memorize melodies more quickly. This aspect of his work could lead to future investigations into how vocalists learn instrumental vocabulary.

According to vocal jazz pedagogue Rosana Eckert, Hendricks’ vocalese is beneficial to students as it injects more jazz vocabulary into their brains through a vocal tradition of lyrics. [8] His lyrics not only translate complex instrumental music into language but also tell complete stories while memorializing the epitome of American culture. By intersecting the roles of voice and instrument with English, Hendricks bridged the gap between the voice and the instrument in jazz, and audiences.

At last, Jon Hendricks was a true pioneer and innovator in the world of jazz music. His contributions to the genre were immense and lasting. He played a vital role in the development of the vocalese style, which has since become a staple in jazz music. Hendricks’ legacy is not only evident in his numerous recordings and performances but also in the many musicians he influenced and inspired over the course of his career. His music continues to inspire new generations of jazz musicians and his impact on the genre will be felt for years to come.

References:

-

Jazz At Lincoln Center. Jazz Congress 2021: Jon Hendricks at 100 — Remembering a Legend ↩︎

-

Jazz at Lincoln Center’s JAZZ ACADEMY. The Poet Laureate of Jazz, Jon Hendricks (Part 2) ↩︎

-

Jazz at Lincoln Center’s JAZZ ACADEMY. The Poet Laureate of Jazz, Jon Hendricks (Part 2) ↩︎

-

Martin, L. E. Validating the voice in the music of Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. ↩︎

-

Martin, L. E. Validating the voice in the music of Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. ↩︎

-

I Remember Clifford. Secondhand Songs. February 24, 2021 ↩︎

-

Martin, L. E. Validating the voice in the music of Lambert, Hendricks & Ross. ↩︎

-

Rosana Eckert, interview by Lee Martin, February 27, 2015. ↩︎