This commentary discloses the process, in which I have developed my research methodology, and the principal theoretical proposals to which it has lead. The core elements of both of these aspects—how these proposals have been formulated and presented as well as what they mean—can be seen as the thesis’ main contributions to knowledge. Foregrounding the how with the what and acknowledging the impossibility to ultimately separate them dislodges to some extent the division into art and research, which is in my opinion one of the fundamental aspects of artistic research in general.

While the research practice has mainly been assembled in and around live events, I have attempted to transport some of its artistic qualities to this digital space, especially in the sections on the two examined artistic parts, A Reading of Audience and Audience Body, and in the underlying architecture of the publication, which is structured by the braiding of the motif threads into a theoretical model.

Below I will briefly recap the fruits of this research process in terms of what the research community and other readers could benefit from it.

Reading events as a presentation format

Methodologically the research presents three more or less original contributions. Firstly the research presents a format for reading events as an intermedial practice which bridges and negotiates between the genres of academic writing and performing arts. In artistic research, the canon and the styles of academic writing are both followed and experimented with. In my case, experimentation has taken place through writing for specific and collective events of reading, in a way that these specific conditions of reading are also explicated. I have attempted to enable a contemplation of the phenomenon of audience in situ via the genre of esitystaide/beforemance art: both within the artistic practice of preparing an esitys/beforemance and in the parapractice of audience membership at the moment of reading.

Since my aim has been to address the audience as a collective body, I have written by projecting towards the event of reading and the conditions that the audience body will then experience: its site, timing, the assumed type of participants and so on. I have taken special care regarding the assumed experiences of reading by a collective audience body, trying to guide and seduce them through my lines of thought. This care can be witnessed in the dramaturgical choices and aesthetic features of the works, visible in the manuscripts included as an appendix as well as in the presentation of the research practice in Chapter 4. I have thus addressed the audience body, but I have also aimed at equipping the readers with a similar address, offering tools for observing what is taking place at the moment of reading and how different thinkers could have articulated it.

At the beginning of the process, academic references and theoretical thinking were more explicit and visible; towards the end I focused more on the sensuous and artistic qualities of the events, making references more covert. In my opinion through this process theoretical thinking has permeated art, smoothening the edges of their contact. When thinking is presented as a reading event in the context of artistic research, the presenter will prepare not only the intellectual and aesthetic qualities of the text, but also materialities of its reading, the use of time and space, light and sound. These factors contribute to the way this thinking is accessible to the audience body and to the emergence of new thinking within the event.

Experimentation, iteration and dialogue

Secondly the research introduces a way of accumulating knowledge through an experimental, iterative and dialogical artistic research practice. The reading events that constitute the Draft series are experimental: I have prepared a textual performance, realized it with a live audience and evaluated this experience based on audience feedback and my own observations. Then, informed by these experiences, I have prepared a new experiment for another context. I have iterated this structure multiple times, forming a series of experiments. Each experiment is devised in a situation-specific way, for a particular context, place, time and in some cases even to particular audience members.

A Reading of Audience, the second examined artistic part, works as a clear example of this format of practice. The process of making the work is composed of 19 readings. During each reading the whole script is read by the attendees, with free-form discussions in the intermissions and after the reading. In the beginning of the process these readings were attended only by the working group, after which invited readers were added. The last eight readings were public beforemances. In between each iteration, both before and after the premiere, I altered the script, rewriting parts of it based on audience feedback and observations made by myself and the working group.

Through this experimental and iterative practice, theoretical ideas were conceived, formulated and reformulated—performing a way of generating theoretical thinking via artistic practice and in collaboration with audiences. This iterative format also reduced the difference between the preparation phase and public beforemances. The peak of the process at the premiere was to an extent blunted and the audience was invited to do more or less the same thing the working group had been doing before. Both the preparation phase and the public phase were experimental, iterative and dialogical.

After the whole run of these readings I interviewed 17 audience members and used their comments as material for the second examined artistic part, the Audience Body. Firstly I edited a complication of voices from the interviews and played it at low volume from three speakers situated in the auditorium area of the space. Secondly I prepared a set of cards with quotes and thoughts from my previous audiences as well as from my source literature. The cards were spread out on the floor of the auditorium like a memory game. Thus audiences took part in the writing of the work.

The parapractice of audience membership

Thirdly I have included the parapractice of audience membership as a significant part of my research. The term parapractice aims at acknowledging the qualities of audience membership, especially in relation to artistic practices, and its importance to my research. It suggests that audience membership is repeatedly exercised in practice and that it accumulates skill and knowledge. That being said, it does not in most cases aim at this accumulation or at the production of anything. While a doctoral research process needs to produce a thesis, parapractice does not, in my interpretation, need to be productive. Instead the parapractice of audience membership has other functions such as fostering the potential for transformation. It is a submissive state of resonance, in which one is awake and dreaming at the same time. While this commentary is written by me, it could not have come about without the artists, whose work I have had the privilege to audience. I propose that the parapractice of audience membership is an undervalued and integral part or companion of artistic practices in general. My personal parapractice is documented in an appendix as a commented list of performances which I have attended as an audience member. A previous version of the same list was installed inside the Audience Body as a reading device, which was suspended across the space. Furthermore, I suggest that the parapractice of audience membership can be developed into a practice of audiencing and that there are some examples of these kinds of practices on the field of art and, possibly and with some reservations, on the field of spiritual practices.

T h e a u d i e n c e b o d y

Mentioned already in its title, the audience body is the central concept of the commentary; it is also the main contribution of the work in terms of academic discourse. It has emerged through the research practice and has then been developed to account for the phenomenon it refers to—accumulating finally in a conceptual model of how audience bodies form, are sustained and disappear. This model, created gradually through the whole of the series of artistic works, was performed more or less in total in the second examined artistic part, Audience Body. In addition to the obvious title, I addressed the actual audience bodies that attended the work through embedding conceptual thinking in the artistic components of the work, as shown below.

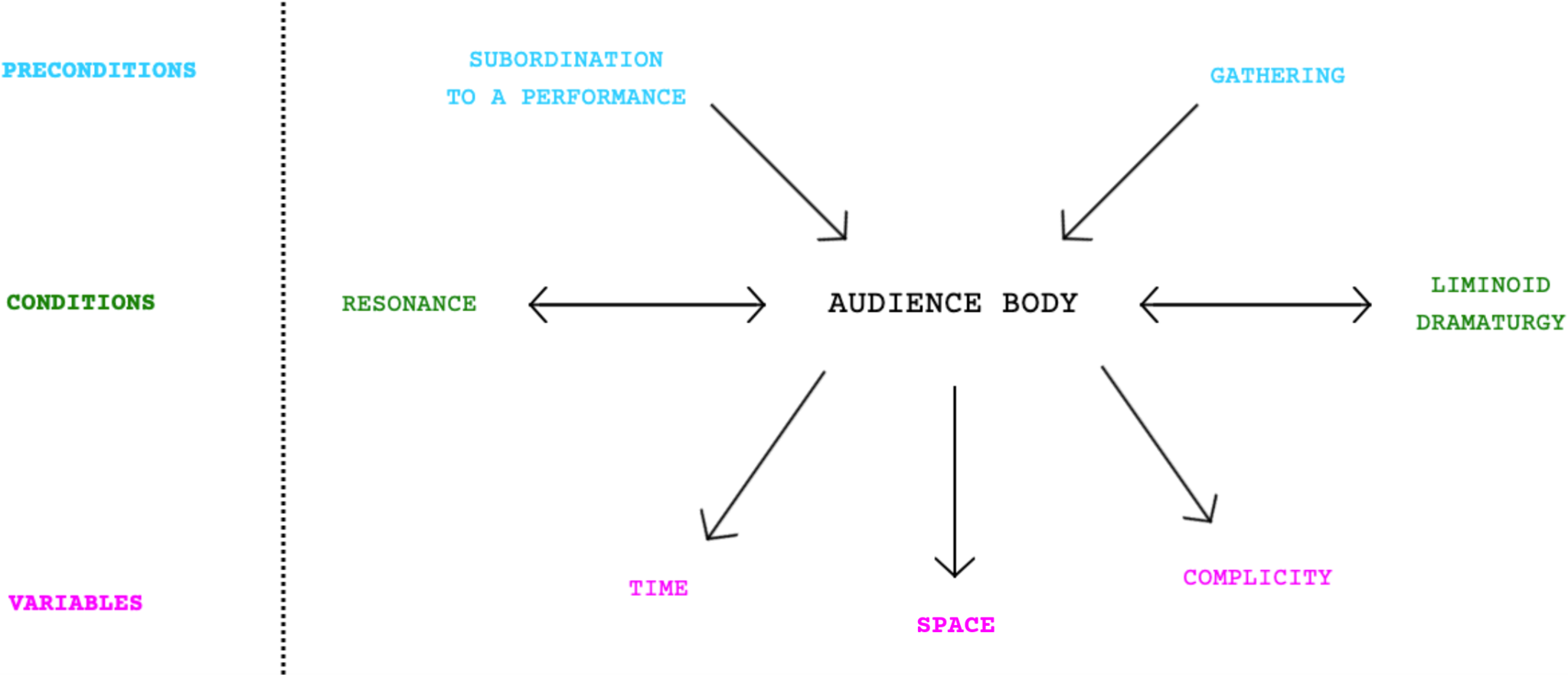

The concept of the audience body presented here is composed of three facets: preconditions (enabling the appearance of an audience body), conditions (defining the way it is sustained) and variables (describing in simple terms the attributes, which determine its quality). They in turn consist of seven components.

Preconditions

The two preconditions are subordination and gathering: audience bodies are formed by individuals who gather as a response to performative action, in relation to which they submit to a subordinate position. The opening gesture of Audience Body was the prologue in the form of a folded-A4 sheet, with the words [open at the same time with the others] in its cover. When audience members had received the sheet, they were guided to the auditorium. From then on, the esitys/beforemance proceeded without the interference of the makers. The audience decided together, when (or if) the folded sheet was opened and the esitys/beforemance thus commenced. Inside the fold, there were simple instructions on how to operate the space and a small piece of edible paper with the word “audience” in it. The text asked the audience members to eat the word, after which they could enter the stage. The prologue introduced several components of the audience body at the same time: the subordinate position the audience had in relation to the author (since the first thing they read was an order), its complicity to the appearance of the art work (it would begin by their synchronized gesture), the plurality that resulted from the act of gathering (via the negotiation, which turning the page at the same time required) and its corporeal nature (through eating and digesting themselves). Subordination was from then on maintained through manifold gestures that would sustain the interest and obedience of the audience.

Since the beginning of my research process I had been processing the “secondary” nature of audiences. It seemed somehow both self-explanatory and something that I did not find in the research literature. The need for “emancipation” that Jacques Rancière had articulated stemmed from this inferior position in relation to the makers of any specific art work. In my opinion, Rancière has a point: to be a member of an audience is not of lesser value than being its maker. But this claim needs amendment: the audience is procedurally and due to its function subordinate to the performance, to the active initiative of the makers. This position is well illustrated by a comparison to BDSM practices, in which power play is consciously and with procedures of consent used for purposes of erotic pleasure. In these practices, submission is a chosen role and, contrary to intuition, can be a position of the highest power. The power dynamics that are instigated by a simple role division are complex. I propose that the same goes for the position of beforemance audiences. They consent to a submissive position in order to enter a complex dynamic of power, exchange and co-creation. When writing my experiments, I used a lot of time to craft the distribution of agency and the way a resonant condition is enabled. I also noticed that failing to uphold subordination would dismantle the audience body. Based on my research, in order to summon and sustain an audience body, the work needs to engage and hold the attention of the audience body via a resonant background mode and careful delivery of agency.

The other precondition disclosed by the invitation in the cover of the prologue is that of gathering. This was another feature I had been contemplating from the start: how to address the plural nature of audiences. I felt that this was also somewhat overlooked by the topical art discourse and also much of the research literature was more focused on the individual spectator due to the roots of reception studies in the literature and fine arts. I found some corroboration for my interest on plurality in theatre studies and Denis Guénoun’s term gathering, referring to the theatre of Ancient Greece, attracted my interest. Guénoun suggested that in an amphitheatre, where the auditorium was curved, the audience could witness not only the performance but also themselves as an audience. This fit well with my definition of the local genre of esitystaide/beforemance art—it also was based on performing something while making the audience conscious of and attentive regarding their own position. My research practice iterated this dynamic.

I lingered on these histories in the A2-sized book What if audience is a charge between in and out, which was set up as a component of Audience Body in a way that invited multiple audience members to read it at the same time. Gathering seemed to accommodate the way audience bodies appeared as plural in the first place. It was an act which transformed multiple individuals into one temporary entity. When I augmented Guénoun’s definition of a gathering with Dorothea von Hantelmann’s inclusive proposal, I could conceptualize the position of performing arts sufficiently in relation to other genres of art. This is further discussed below along the aspects of time and space. To put it briefly, according to Hantelmann, gatherings can be collective but also individual, allowing for, in my terms, scattered and asynchronous audience bodies. Via the research process, “gathering” came to mean the fact that people are linked by a shared membership in an audience of a specific artwork, whether they physically meet or not. The quality of this shared membership equals the kind of collectivity the artwork in question creates—which in turn contributes to its political content. Especially when made aware, as in my works, of their membership in a collective audience body, the members were invited to take part in political thinking.

Conditions

If preconditions enable an audience body to appear, conditions are the way it is sustained. Resonance has been mentioned already several times in this concluding chapter. The concept is borne from the initial subordinate position of an audience body. As already mentioned, this position is based on a deferral of action and consequent distribution of attention to those who perform or that which performs. My proposal here is that when the possibility for action, agency and performance is (albeit with consent) repressed, another quality will replace it. That quality is resonance—a modification of the much-used term reception. Through resonating with the input given by the performance, the audience body is both (a part of) the medium and the recipient(s). Resonance is terminologically in line with audience, since both refer to the category of sound. I use it both in a physical and a metaphoric way, continuing from Ana Pais’ concept affective resonance. Following Pais, resonance is connected to how a performance makes audiences feel. It implies being open to the influence of others, and ready to be changed by it. An audience member can affectively resist this influence, but being a part of an audience body does not support this resistance; respectively this resistance can also be interpreted as a resonance of sorts. Resonance is the default state of an audience body, constantly challenged and mitigated by the distribution of complicity, which is also essential to audience bodies.

The second condition of audience bodies, liminoid dramaturgy, accounts for the temporary nature of these bodies; their formation, endurance and demise. It is based on the anthropologist Victor Turner’s concept liminoid, which refers to the lightly altered state of affairs, which an art experience may induce. In my terms, this altered state is namely the audience body. The prologue of Audience Body was coupled by an epilogue of the same format, a folded A4 sheet with the sentence [open at the same time with the others] in its cover. While during the 90 minutes between the opening and closing scenes the audience could roam freely in the space, the prologue and the epilogue gathered them on the seats of the auditorium. Together these two scenes marked the structure of a liminoid dramaturgy. The prologue emphasized the preliminoid phase, during which the collective audience body was formed. The transition to the liminoid state was accentuated further through the quasi-religious eating of the body of the audience. The time-space between the prologue and the epilogue—the inhabitation of the stage between the two phases in the auditorium—was effectively the liminoid state. The epilogue highlighted the postliminoid during which the collective audience body started to disintegrate and was asked to end the beforemance.

Variables

The quality of audience bodies is defined by three variables: time, space and complicity. Actual audience bodies may be situated anywhere on these scales that stretch between six extremities; they may even stretch on an axis, move or be situated on several points on it. The cubic model composed of these three variables and their six extremities was included as a part of Audience Body in the enveloped Love letter. The letter contained a piece of thick paper with the blueprint of the cube in it, available to be folded into its three-dimensional shape by the reader.

The aspects of time and space are best exemplified by the diptych Time to Audience—Drafts 28 and 29. Both parts of the work were composed of 40 rolls of paper. The first part of the work, situated in the context of a contemporary dance festival, was structured so that the audience would read these rolls at the same time but in different places. In the second part, situated in the context of an art exhibition, the opposite was the case: during the 40 days of the exhibition, each day one roll was available for the audience to read. These works concretize the temporal extremities possible for audience bodies: attending the work at the same time, i.e. contemporaneously or attending it at different times, i.e. asynchronously. Similarly they concretize the spatial extremities: attending the work in different places, i.e. in a scattered formation, or attending it in the same place, i.e. in a dense formation.

Contemporaneous audience bodies are common in performing arts. This contemporaneity is most exaggerated in traditional performance art, in which it is common that performances are not repeated and the work is experienced only once, excluding those who experience the work via documentation. Audience Body followed the tradition of the theatre: the whole audience body was divided into several contemporaneous audience bodies who experienced different iterations of the same work. However, the audience bodies that followed each other at the same venue, were partly integrated into one big audience body via the transformation of the space during the run of performances. The roll-shaped Time and place contemplated the aspect of time through the act of unwinding the roll when reading; strips of paper accumulated into larger and larger piles when the work was repeated. The Love letter asked the reader to destroy it after reading, which resulted in a decreasing number of envelopes on the wall and a beautiful audience-made landscape of carefully installed remains, which also accumulated. This transformation of space made each audience body aware of its extensions in other repetitions of the work.

In addition to time and space, the quality of audience bodies is defined by their complicity, a term borrowed from philosopher Reza Negarestani. An audience body can be performative, taking actively part in the realization of the work. Performative audience bodies gather in works that are categorized as participatory, but also audience bodies summoned by traditional theatre are to an extent performative through their reciprocal visibility in the same space. Contrasting this performativity, audience bodies can also be autonomous: detached from and unable to influence the art work itself. Autonomous audience bodies are common in genres of art, in which the art work is typically finished before it encounters its audiences: for example literature or film. That said, complicity is an especially complex variable and intertwines (in addition to explicit participation) to the ways the audience is expected to surrender to the mercy of the experience or “fill in the gaps”, to continue with their imagination from were the makers left off. Thus complicity is also linked to the discourse around the concept of immersion, which was in the Audience Body addressed by the component Immersion: eight underwater books in a pool meant to be read while keeping one’s hands in the water. To oversimplify, in a participatory work, the complicity of the audience body is explicit. In an immersive work, complicity is implicit. Participation suggests an invitation to shape the work, while immersion denotes a state in which the boundary between the work and its discontents dissolves.

In the Audience Body I tried to balance between these extremities. The audience bodies were thoroughly complicit in its beforemance. From the moment of opening the prologue they were actively engaged with their bodies and choosing their route, tempo and reading, manipulating the objects of reading with their hands. They ate paper, unwound rolls, opened envelopes, destroyed letters, wet their hands and turned pages. However, while their role was active, they were also just reading what I had written before, unable to modify the text—even unable to speak, even if this was not instructed by me. The amount of text was considerable; I flooded their experience with my words and sentences. I attempted to retain and protect their right to stay out of the spotlight and remain in a resonant mode.

B e f o r e m a n c e

Audience bodies are summoned by all kinds of art works, but my interest in the phenomenon has evolved in a specific field of art, one which emphasizes their complicit yet resonant role. This local genre of performing arts, in which I situate my artistic practice, is called in Finnish esitystaide. In the commentary I propose that this term does not so far have a proper translation in English, for which reason I have used my own neologism beforemance. My artistic research practice pays respect to what I define as the main ingredients of beforemance.

My proposal is that beforemance art is a reformation movement of theatre that has developed in the capital area of Helsinki during the past 30 years. Like theatre, it is based on the asymmetric relation between a performance and an audience body, but through the influence of other genres of performing and live arts, it has rendered some of the defining features of theatre, such as the theatre building, a traditional play text and actors as trivial. For example, in the research practice exposed in this commentary I have deferred live performers and instead created beforemances through staging texts for collective audience bodies to read.

I have briefly outlined the way this genre and the term referring to it have developed historically and proposed also a way it could be defined and differentiated from other genres. Unlike performance art, it needs an audience body. Apparently more than Live Art, it is based on the theatrical asymmetric relationship between a performance and an audience body as well as to collective practices originating from the genre of theatre. Compared to theatre, it does not take its audience relations as given. It is a local phenomenon, but it has developed as a part of European performing arts and is not in any fundamental way separate from what takes place elsewhere. In my definition its defining features are common to all arts, it just happens that in the context where I have developed my practice, they are especially tangible. The non-triviality of the mode of attendance of audience bodies, typical for this genre, affords the audience with the task of resituating themselves in the sphere of influence of each idiosyncratic performance. This challenge may enable a resistance to the production of distance, which is linked with a bourgeois position where responsibility for the world is denounced.

For the local readership, this work offers an articulation of the development of the genre of esitystaide and adds a proposal in the discussion regarding the difference of esitys and performance. For the international readership, I hope to expose some of what has taken place in this local scene in the past 30 years and what these developments could imply regarding performing arts in general.

P o s i t i o n i n g t h e r e s e a r c h e r

Finally, I have engaged in a process of finding a way to position myself as a researcher in relation to my work and the academic context. This problematic has been present from the start when trying to find ways to do artistic research and at the same keep the focus on the audience instead of what takes place on stage, however that is defined.

During the public performances of Audience Body at the Zodiak Center for New Dance in November 2022 I noticed something interesting. During the draft series and also in A Reading of Audience I had taken part in the readings among others. Like explained above about the process of A Reading of Audience, I considered it a practice, which took place both before and in the public beforemances. But now, in Audience Body, something changed. Together with lighting designer Nanni Vapaavuori we welcomed the audience when they entered the space and handed over the prologues to them. After that they opened the folded sheets, launched the performance and entered the stage. This time I did not join them. Instead I stayed in the auditorium, watching them, fascinated, for the whole duration of each iteration.

My conclusion is that through the practice I had cleared a path for myself to become an audience of audiences. Before this, it had felt uncalled for and intrusive. Now, it seemed totally fine and appropriate. No-one seemed to care if I watched or not. I was suddenly a (relatively) autonomous audience of a performative one.

I don't know, how to repeat this and how would this develop into a contribution that would benefit others. I think it owes to a long process of sincere attempts to listen to the audience and what is going on in them; a long process of creating conditions in which they would want to embrace their complicity.