Introduction

Online gridded soundmaps have recently gained popularity as a platform to engage communities with their surrounding soundscapes and physical environments. However, they have also received criticism with regards to their effectiveness in gridding sound and its personal significance (Ceraso 2010; Waldock 2011; Ouzounian 2014). What is often overlooked, or even omitted, are memories, emotions, thoughts, and associations, a criticism also made of traditional Western cartography in general (Wood 1992, 2010; Caquard 2013). In this article, I argue that soundmaps have the potential to chart personal and collective, imagined and remembered, and invisible and physical relationships between sound, the world, and ourselves. I call these peripheries of lived experience “in-between-spaces,”[1] and I argue that soundmaps can only truly document listening if these spaces are mapped. However, this will not be achieved unless we adopt a more imaginative approach to cartography, traversing the boundaries of the grid.

Drawing from projects that already map sound in unconventional and creative ways, including my collaborative project with Fionnuala Fagan, Stories Of The City: Sailortown (2012), this article explores forms of soundmapping that expand the online gridded soundmap platform. Not only do these examples map the invisible “in-between-spaces” of personal relationships to sound, but also the unseen spaces of urban architectures. Sound is intangible, ephemeral, and invisible in nature, and therefore possesses profound potentials to map invisible geographies, which might otherwise lay silent. We will only bring voice to these other layers of experience if we embrace cartography as a creative and potentially empowering platform.

What is a map?

To open this discussion, it is important to first consider what is meant by the term “map.” Perhaps the most commonplace answer would be a piece of paper or screen consisting of lines that accurately plot physical and spatial aspects of the world within a grid. However, if we look back as far as the Middle Ages, there was no word for map; instead they were called pictures. These pictures not only mapped geographical information, but also operated as, “an open framework where all kinds of information might be placed […] not unlike a chronicle or narrative” (Harvey 1991: 19). This earlier definition of maps is contradictory to contemporary assumptions of their overarching validity and accuracy, and calls into question the trust and power that is placed in the hands of their creators.

In You Are Here, Katherine Harmon states that “humans have an urge to map – and that this mapping instinct, like our opposable thumbs, is part of what makes us human” (Harmon 2004: 10). While You Are Here’s examples of imaginative cartographies from various points across time and place echo Harmon's belief, all too often mapping is left to the few and the powerful. Harmon adds that “the mapping instinct is of the ‘use it or lose it’ variety” (Harmon 2004: 1), and I argue, to “lose it” is to relinquish a certain amount of power. To map is to represent your surroundings and your perceived realities. We do not exist in lines and grids: we hear, smell, touch, taste, imagine, remember, and encounter. To allow these experiences to go undocumented in cartography can relinquish their significance and only communicates part of our surroundings and ourselves.

As advocated by critical cartographers Sébastien Caquard and Denis Wood, two-dimensional maps that aspire to represent scientific and mathematic accuracy are not always the most effective or truthful representations of the world: there are other ways for us to map ourselves, our communities, and our surrounding environments. Much as maps were perceived as pictures in the Middle Ages, Caquard argues that they are in themselves a narrative and inextricably intertwined with personal association, emotions, and memory (Caquard 2013). This understanding of maps, Denis Wood argues, liberates us to ask, “what if map making were an expressive art, a way of coming to terms with place, with the experience of place, with the love of place” (Wood 2010: 14)? Wood argues that if maps were to act as poems, for example, then they would have to map how a specific thing in a specific place is perceived by the individuals who experience it. In addition, Wood suggests that it is not only the map that is a form of artistic expression; the process of cartography is, in itself, a creative act.

[1] A term partly inspired by David Pinder’s discussion of Janet Cardiff’s soundwalk The Missing Voice: Case Study B (1999) in his article “Ghostly Footsteps: Voices, Memories and Walks in the City” (Pinder 2001), which will be discussed in more detail later in this article.

Cartography as Artistic Expression

There are countless examples of artists who have embraced the potentials for creative expression in cartography. For example, contemporary writers, such as Robert Macfarlane, describe routes and journeys in text that charts alternative travel itineraries. Macfarlane’s three books to date – Mountains of the Mind (2003), The Wild Places (2007), and The Old Ways (2013) – divulge not only the geographical aspects of their travels but also the historical, experiential, and psychological facets of being in place. Likewise digital, visual, and installation artists have engaged with cartography in experimental ways. For example, R. Luke DuBois’ A More Perfect Union (2010–2011) plots the prevalence of words found within American online dating profiles such as funny, sexy, or shy, across a series of USA national, state, and city maps. In contrast, Richard Long’s practice embraces the art of documented walks across many miles, which generate sculptures, photographs, text and drawings, plotting his journey along various landscapes and terrain.

What differentiates these examples from traditional concepts of cartography is that they map intimate and personal aspects of self and site. Additionally, Macfarlane’s individual observations, DuBois’ cartography of love, and Long’s documents of walking openly profile the artist as the author. These maps are documents of the personal by individuals and, as Caquard argues, “indicate the importance of spatiality in the arts and the social sciences” (Caquard 2013: 136). Cartography and artistic expression enrich each other, strengthening their relevance with our experience of the world. Together they invite us to consider the many different aspects of our surrounding environments and ourselves.

Soundmaps

How then can sound be used as a creative cartography? Two early examples are the World Soundscape Project (WSP) and Max Neuhaus’ LISTEN (1966). The WSP, founded by Murray Schafer in the late 1960’s, aimed to collect and preserve field recordings of sounds they perceived to be under threat from the dominance of human noise. This ambitious task subsequently initiated their interest in sound as cartography, locating field recordings across the globe, and the development of soundscape composition. LISTEN, meanwhile, took audiences on walks in which people were encouraged to attend to the sounds they encountered. Through this process Neuhaus, much like Schafer, hoped to “refocus people’s aural perspective” (Neuhaus 2004: 2). LISTEN established a more communal form of listening, as compared to the WSP’s approach, collectively mapping sounds onto routes traversed by a group.

Throughout the decades that have followed, sound art has profoundly questioned conceptions of space, time, site, architecture, aural imagination, and their interlocking relationships. Indeed, art works that interrogate site and place through sound already overturn traditional notions of cartography’s rooting in physical, gridded land. As technologies developed in the late twentieth century, audio became portable, providing freedom of movement across various topographies. Janet Cardiff’s soundwalking practice, which emerged during the 1990’s, explored and established how locations can be physically navigated through the medium of composed sound. Her soundwalks, such as Her Long Black Hair (2011) and A Large Slow River (2000) combine voice with composed soundscapes in order to map a narrative across a specific route. These pieces form hidden layers of place in which the listener is centrally aligned.

In “Ghostly Footsteps: Voices, Memories and Walks in the City,” David Pinder discusses Cardiff’s soundwalk The Missing Voice: Case Study B (1999), set within London’s Whitechapel and Spitalfields districts. Pinder describes how The Missing Voice evokes “a sense of participating in a book or a film as you [the listener] are caught up in the narrative.” However, the listener is simultaneously “immersed within the space-between it creates.” This “space-between,” Pinder explains, lies “between fiction and reality as [Cardiff’s] sounds merge with those around you” (Pinder 2001: 2-3). In all of Cardiff’s soundwalks her composed audio mingles with the walker’s physical surroundings: buildings and streets, passers by, and seasons that change. Pinder sees this boundary between fiction and reality as an “in-between-space” accessed through the act of listening and walking.

The Emergence of Soundmaps

The invention of geolocative media has enabled artists to spatially grid recordings of sound within artistic projects, such as Stanza’s Soundcities (2004; 2005-2008). In the project’s initial form, Stanza uploaded his own field recordings to an online mapped database. From 2005-2008 Soundcities became an open source database where anyone could contribute their own recordings. This later format echoes that of the contemporary Google API soundmap, embraced in recent years as a new, interactive way of sharing and archiving soundscape recordings. In the UK and Ireland alone their scale ranges from the UK Soundmap, with currently over 2,000 recordings, to more localized examples, such as Limerick Soundscapes, with currently less than 50.

Through online platforms, such as Google Maps, communities can easily record and upload their own recordings, which are easily accessible to users by clicking at their associated locations on a gridded map. Their appeal lies not only in the use of new technologies, such as smartphones and GPS, but also in their capacity for community engagement. They offer a relatively uncomplicated way for potentially large numbers of people to engage with sound and their local environments quickly and relatively cheaply. This process, in theory, enables communities and individuals to create soundscape archives that publicly share community interests and identities, democratizing shared narratives of place and space.

Democratizing or Homogenizing?

Soundmaps do present a readily interactive platform on which to share recordings with local and online communities, and for certain objectives, such as analyzing noise pollution, they can be extremely valuable.[2] However, if they are to engage communities with their surrounding soundscapes, as many claim or endeavor to do, they must represent these communities’ listening experiences. Mapping static gridded sound does not always effectively do this. Communities do not listen solely with their ears, but also with their bodies and their minds.[3] Steph Ceraso argues in her article “The Sight of Sound: Mapping Audio” that gridded boundaries “don't apply to sound. Unlike maps, sound does not rely on surfaces or depths; rather, it penetrates them” (Ceraso 2010). The gridded medium of the soundmap detaches sound from its fundamentally ephemeral, intangible, and invisible qualities. This then dislocates sound from the experience of listening.

When we listen, we actively draw from thoughts, associations, and emotions, all of which shape our individual relationships with different sounds. These are different aspects of memory that sound, like many other senses, can induce. In “The Sound of Memory,” Lesley Morris states that the sound of memory is “more elusive and perhaps more transient than the visual site of memory” (Morris 2001: 38). Sound is traditionally more associated with subjectivity than accuracy. However, this perception has shifted slightly in more recent years. In an interview with Angus Carlyle, environmental artist and writer Andrea Polli discusses how she believes“there is […] a strong memory component with sound, that sound can be associated with remembering and with clarity; and that this combination is a powerful one” (Lane and Carlyle 2013: 23). The ability to record sound and fix it spatially within a visible grid has undoubtedly contributed to the sound-memory–clarity relationship Polli describes above.

However, this is not to argue that sound is in anyway superior to sight, or any other sense, with regards to clarity and memory. Morris concludes that “my call for a turn to the aural is not a call for a move away from the visual; rather, […] we can find, in the interstices between sight and sound, additional layers in the production and creation of memory” (Morris 2001: 377). These additional layers of memory are parts of the “in-between-spaces” of lived experience I argue should be documented in soundmaps. Like Morris, I do not believe soundmaps must move away from the visual and physical, but if we are to harness sound as a creative and expressive cartography, we must map listening rather than solely fixed sound.

As Gascia Ouzounian discusses in “Acoustic Mapping,” it has been argued that the soundmap’s "temporal or geographical reach is so broad or disconnected that any meaningful engagement beyond ‘listening to field recordings tagged on a map’ is effectively extinguished for some audiences” (Ouzounian 2014: 71). Therefore, if they are to truly map specific communities’ relationship with sound, the significance of these recordings, including the triggered facets of memory discussed above, must somehow also be plotted. There must be a consideration of how engaging soundmaps actually are for users. If we fail to do this, we cannot expect users and contributors of them to actively listen to their plotted recordings any more than we can expect communities to actively listen to their every-day surroundings.[4] Therefore, If nothing else, soundmaps must offer greater human context for the sounds they plot, just as one might do if attempting to engage another with their listening out “in the field,” face-to-face.

As well as the criticisms discussed above, in “SOUNDMAPPING: Critiques And Reflections On This New Publicly Engaging Medium,” Jaqueline Waldock further critiques soundmaps for foregrounding public sounds, as opposed to the private or domestic:

The connection between sound and person, person to emotion and sound to effect, is key to both the listener and the contributor for understanding the space as sound and sound as life. (Waldock 2011)

Here, Waldock argues that in excluding the individual, private and domestic from soundmaps, we exclude some of the most fundamental facets of listening. Even though space has an important relationship with sound, sound has an important relationship with what it is to exist as a human being, or, as Waldock states above, with “sound as life.”

However, if we are to achieve this within the soundmap format, we must embrace the more progressive and experimental approaches to cartography proposed by Caquard and Wood above. For example, although Ceraso’s argument outlined above asks important questions of soundmaps, it also enforces unhelpful restrictions upon cartography. She argues that “sound is experienced as simultaneously interior and exterior, but mapping (in the case of place) only deals with exteriority” and furthermore, that maps “rely on surfaces or depths” (Ceraso 2010). Caquard and Wood both argue that maps can indeed plot the interior and domestic, along with the ephemeral and invisible. Therefore, I will now discuss three examples of soundmaps that expand the boundaries of the grid to chart Morris’ “additional layers of memory” and Waldock’s “sound as life”: the “in-between-spaces” of lived experience.

[2] Two examples of soundmaps that have been used to measure noise pollution are: Murphy, Edna, Henry J. Rice and Craig Meskell (2006). Environmental noise prediction, noise mapping and GIS integration : the case of inner Dublin, Ireland. Paper presented at the 8th International Transport Noise and Vibration Symposium, St. Petersburg; and Ramanujan, Krishna (2010). “Acoustic maps of ocean noise reveal how shipping traffic affects whales.” Cornell Chronicle.

[3] This is not to argue that soundmaps only chart human as opposed to non-human sounds. They can indeed offer a greater understanding of non-human soundscapes.

[4] Indeed, it is presumptuous to suppose that many people do not already listen to their every-day surroundings. However, if the endeavor of many soundmapping projects is to engage communities with their surrounding soundscapes, they must therefore believe that many people currently do not.

Soundscapes of The Black Hills

Jennifer Heuson’s Soundscapes of The Black Hills maps recordings of various locations in The Black Hills, an area nestled on the western border of South Dakota. Heuson uses field recordings to reflect upon some of The Black Hills’ most legendary locations, such as The Badlands and Mount Rushmore, and the many tourist destinations that now populate the area. The project uses an online gridded map, much like the soundmap platforms discussed above. However, what is distinctive from other projects of this kind is that Heuson maps The Black Hills as artistic expression.

With each recording, in addition to a contextualizing image, Heuson includes text that places her recording process firmly within these soundscapes and their locations. For example, she divulges that, when making her recording Electric Museum at The Pioneer Museum Hot Springs, SD, "the ubiquitous sound of fluorescent lighting was particularly memorable" (Heuson 2011).

Jennifer Heuson - Electric Museum

Similarly in her recording Buffalo Growl, made at The Wind Cave National Park, she tells us that “two bison herds met near a scenic outlook on this morning. You can hear the two top bulls growling at each other and the snaps of tourists’ cameras” (Heuson 2011).

Jennifer Heuson - Buffalo Growl

This accompanying information provides a context for these recordings, which deepens the listener’s experience of them. Additionally, in the map’s introductory text, Heuson communicates directly with potential users, urging us to:

listen […] to hear the Hills, to hear the Hills as I have heard them […] as I hear them even now. […] It is an encounter that relies heavily upon fieldwork, upon listening and looking and sensing in the field, and upon mediation, the mediation of microphone, of recorder, of film, of computer. (Heuson 2011)

Heuson firmly places herself as the author of this map, the maker of the recordings, and approaches her fieldwork creatively, as “sensing in the field.” However this is not a nostalgic sonic indulgence in The Black Hills. Instead, Heuson actually maps nostalgia itself by documenting The Black Hills’ tourist destinations.

Furthermore, she argues that through approaching cartography creatively and artistically, we can “engage scholarship in a new way” (Heuson 2011). Maps do not need to be authorless or the product of a multiple unknown. Therefore, this map is not data plotted on a grid, a criticism Waldock has made of soundmaps in general (Waldock 2011). This map should be an engaging, creative experience, and, as Caquard proposes above, a narrative that unfolds. A perspective often missing from traditional cartography, Heuson plots the “in-between-spaces” of her artistic experience of mapping The Black Hills. As much as the landscape she documents, her cartographic process is clearly emphasized and vitally present in the map.

Miastofon

The project Miastofon (2014) similarly uses an online platform on which to position field recordings, but unlike Soundscapes of The Black Hills, users must orientate themselves purely through listening. Miastofon maps the Nowy Port district of Gdańsk, but is “purely acoustic” with all “visual aspects […] eliminated, even the cursor” (GrubyPunkt 2014). With regard to Ceraso’s criticism of sound that is fixed within the boundaries of a grid, Miastofon presents an alternative method of soundmapping. Rather than providing a pictorial grid on which recordings are visually plotted, sound is activated by moving a mouse across a blank computer screen. The user must listen in order to locate sounds and gain spatial cues. Gdańsk’s urban soundscape has, rather masterfully, been plotted aurally, providing the user with a vivid sense of the city’s soundscapes.

The project was approached in this way because it aims to represent the orientation of blind and partially sighted people through the city. Members of Gdańsk’s blind and partially sighted community were invited to participate in a series of psycho-geographical workshops. While Waldock argues that “a large majority of the recordings” in existing soundmaps are “tagged in the impersonal” (Waldock 2011), the recordings in Miastofon are orally tagged by the workshop participants. During recorded walks through the streets of Nowy Port, these participants were asked to describe how they experience the sounds of this neighborhood. These recorded discussions are embedded within the map, alongside street sounds and other aural features, foregrounding the participants’ relationships with the sounds present. As the map user’s mouse drifts to another location, conversations and sounds disappear while others begin to emerge.

By navigating Miastofon through listening alone, as users, we gain some understanding of how a blind or partially sighted person might navigate Nowy Port. Additionally, we also traverse Miastofon through the workshop participants’ individual listening experiences and the personal significance of the map’s sounds. Therefore, Miastofon uncovers a mode of orientation that sighted users of the map, and sighted inhabitants of Gdańsk, might otherwise find hard to understand. This mode of orientation is literally given voice by the workshop participants’ discussions. Therefore, Miastofon exposes Gdańsk’s “in-between-spaces” of alignment and navigation, which deviate from society’s more accepted, visually orientated, norms. Miastofon achieves this through the invisible and intangible entities of memory, association, and sound. However, I argue that although these entities are personal and largely unseen, they can also potentially map visual landscapes that have now disappeared due to regeneration and urban development. This leads me to my last example of soundmaps that expand the boundaries of the grid: my collaborative project with Fionnuala Fagan, Stories of the City: Sailortown.

Stories of the City: Sailortown

In 2012, Belfast’s Metropolitan Arts Centre (MAC) commissioned sound artist and singer-songwriter Fionnuala Fagan and I proposed to document the memories of The Sailortown Regeneration Group (SRG) through song.[5] The SRG are a community of people who used to live and work in Sailortown, the old dockside area of Belfast. While the initial aim of this project was to document memories of Sailortown’s soundscape, what emerged was just how much the disappearance of Sailortown’s physical landscape had affected the SRG as individuals and as a community. Therefore, Stories of the City: Sailortown began to map the streets and buildings that had now disappeared, interwoven with the SRG’s personal histories.

The history and community of Sailortown offers a valuable example of the problematic nature of separating lived experience from cartography and the destruction and loss to individuals this can cause. Sailortown was once a bustling dockside area in Belfast with a close-knit community. During the first half of the twentieth century, industrial growth meant the docks became one of the biggest employers in Belfast, comparable with the city’s shipbuilding industry. Technological advancements meant jobs at the docks diminished, and a growing need for road links in and out of the city developed. Therefore, in 1962 the M2 motorway was built, demolishing most of Sailortown’s buildings and streets and relocating families to other parts of the city.

Today, what was Sailortown is mainly populated with an industrial park, modern vacant apartment blocks, car parks and, controversially, a wet-house for recovering alcoholics. Consequently, the name Sailortown is often met with blank faces, as even most Belfast residents are unaware of its existence. Still, the SRG meet in the premises above a betting shop in the heart of what was once Sailortown. The group consists of people who lived and worked at the docks before the motorway was built, and during 2012 Fionnuala and I were privileged enough to hear their stories.

Over six months, Fionnuala and I collected interviews with members of the SRG. Using verbatim text from these interview transcripts, we composed seven songs that represent the SRG’s memories of life in Sailortown. These include not only collective memories on one theme, such as home life or employment, but also individual people’s life stories. For example, The Ghost of Sailortown (Anderson 2012) is about Sailortown’s many ghost stories, while We Would Wait (Fagan 2012) is about one person’s memories of saying goodbye to their father when he went away to work at sea. Better The Devil (Anderson 2012) is about women’s memories of going out as teenagers to dance with sailors at weekends, whereas Mary’s Song (Anderson 2012) is about one person’s story of adoption. The songs also include: The Harbor Lights (Fagan 2012), about collective memories of growing up in Sailortown; Chapel On The Quay (Fagan 2012), about St Joseph's Church, one of Sailortown’s last buildings still standing; and Whitla Street To God Knows Where (Fagan 2012), about people’s frustration of Sailortown’s neglect and demise.

Whitla Street To God Knows Where

Through these personal memories and histories, many of Sailortown’s streets and buildings began to emerge in the songs we composed. For example, Mary’s Song references Corporation Street, which, although it technically still exists, is very much changed now. The Ghost of Sailortown mentions No.19, Pilot Street, which has now disappeared. Even very detailed characteristics of the houses before they were demolished are referenced. For instance, Whitla Street To God Knows Where describes details of domestic life:

There were many red-bricked houses,

With black tar that framed the white washed yards,

A half moon shape,

Scrubbed round each front door,

All the people were so close knit,

They’d have done anything,

For anyone.

As well as referencing the buildings and streets that had fallen into dilapidation, or disappeared completely, the SRG also voiced great feelings of loss and bereavement. It had been extremely difficult to accept the disappearance of Sailortown from Belfast’s physical and psychological landscape, when at one time it had been their home. For example, Whitla Street to God Knows Where declares:

Sailortown streets all gone now but a few,

They raised them to the ground,

It burns me,

A wasteland fly over,

All black tar now,

Famous for ghost stories.

This reference to ghost stories also echoed the general sentiment of the people we interviewed. Sailortown was a haunting as much as a treasured memory, as The Ghost of Sailortown demonstrates:

All the streets are gone,

The whole lot’s away

And they don't even know,

They don't even know where this place is,

Or if it ever even existed.

The project developed further into an installation and live performance exhibited in May 2012 at The MAC. The exhibition featured the seven songs alongside composed soundscapes, objects, images, and text. Each song could be heard through headphones mounted on the walls at different locations in the space. These areas also contained photographs and objects from Sailortown, which could be explored while listening to the songs, deepening their personal context. For example, Mary’s Song was accompanied by a photograph of Mary’s biological mother, alongside a photograph of her adopted mother.

[5] Many thanks to The Sailortown Regeneration Group, especially Marie O'Hara, Marion Steele, Mary Little, Bernie Baker, Sean Baker, Sue Brown, Morris Brown, Seamus Brown and Emilie Hamilton, for sharing their memories so generously. Their words retraced Sailortown.

Mary’s Song, exhibition at The MAC in May 2012, © Isobel Anderson and Fionnuala Fagan

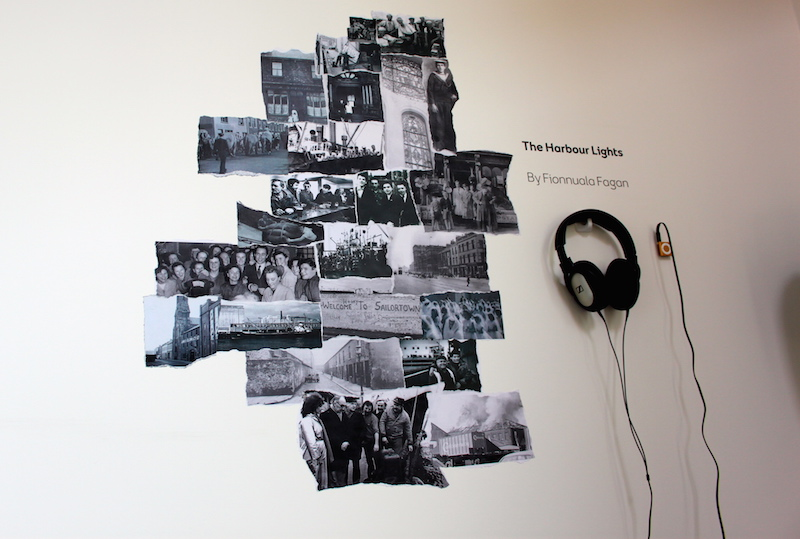

Chapel On The Quay was accompanied by treasured objects from St Joseph’s Church, kindly donated by the SRG, while The Harbour Lights was accompanied by old photographs of the docks at Sailortown.

The Harbour Lights, exhibition at The MAC in May 2012, © Isobel Anderson and Fionnuala Fagan

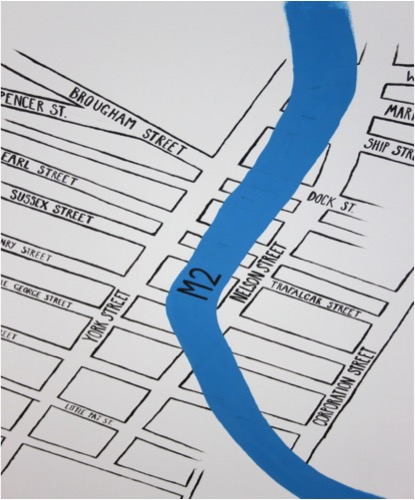

A large map of Sailortown’s now disappeared streets was painted on one wall, with the M2 motorway marked across them where it now stands. This illustrated visually where the streets referenced in the songs were in relation to Sailortown’s current landscape.

Sailortown Map, exhibition at The Mac 2012, © Isobel Anderson and Fionnuala Fagan

The Stories of the City: Sailortown installation was, therefore, a visual experience for visitors as much as an aural one. Rather than separating sound in the form of song and soundscapes, we aimed to contextualize them through the use of images and objects. As Morris argues, regarding the additional layers of memory that can be found in “the interstices between sight and sound” mentioned above, combining the visual, physical, and aural in the installation space strengthened Sailortown’s presence within the work.

In the gallery we also diffused field recordings of the motorway and the sea, which I had made in the early stages of the project. There is an unnerving similarity between these two soundscapes: the sea, which represents what once was Sailortown’s main form of industry, and the motorway, which represents Sailortown’s demise. Therefore, we positioned these recordings at either side of the room, slowly panning them across one another. This meant that they gradually mixed together in the center of the room, while still maintaining their individual characteristics at the room’s extremities.

As an installation and a collection of songs, the project not only acts as an artwork, but also maps a largely forgotten part of Belfast. It could be easy to walk through Sailortown and only recognize the fly over, car parks, and wasteland that now make up its physical presence in Belfast. However, Stories of the City: Sailortown maps the SRG’s individual lives, personalizing the sounds of the motorway, the sea, and the content of the songs. This plays an important role in re-mapping areas of a city that have fallen into degradation or have disappeared completely.

Similarly, Denis Wood also mapped his local neighborhood, Boylan Heights, when its landscape was threatened with the building of a new road. Rather than an impersonal piece of anonymous land, Wood likewise wanted to consider alternative ways of viewing his neighborhood:

[…] there were other ways of thinking about it [Boylan Heights, IA] as a neighborhood, that it was some sort of community, or as a marriage of community and place, or as those people in that place, their relationships, and their ways in the world. (Wood 2010: 16)

I hoped that Stories of the City: Sailortown would similarly map the personal value of Sailortown in order to question Belfast’s present-day relationship with this area of the city. The project forces people to look beyond the flyover and car parks to the architectures and community that once stood in their place. Additionally, the invisible qualities of sound and storytelling gave voice to the SRG’s personal and invisible, but still very important, internal constructions of Sailortown. This was an internal mapping embedded within their minds, which Carol Becker argues is integral and distinctive in our present positioning in the world:

[…] such virtual spaces also can become sites of true interrogation that engage the senses, the memory, and society while critically challenging us to find, and define the phenomenological world and our place within it. (Becker 2009: 26)

Even if a place purely exists through our memories or imaginations, and potentially our listening, it can still be vitally important in negotiating our present placing in the world. As demonstrated by Soundscapes of The Black Hills, we all map individually, and as Miastofon reveals, accepted ways of orientating and experiencing a city can be far from many peoples realities.

Since its installation at The MAC in 2012, Stories of the City: Sailortown has been made available online, and the songs have been archived in the British Library in London and the Linen Hall Library in Belfast. This enforces the project’s significance as a document of this lost district, and the installation broadened people’s awareness of Sailortown and its past. One visitor to the exhibition said that, “[i]n four years in Belfast I have taken the M2 various times. I had never heard of Sailortown before this, and would have not known if this project had not taken place” (N.N. 2012).

However, Stories of the City: Sailortown does not operate as a traditional map. In comparison to Soundscapes of the Black Hills and Miastofon, Stories of the City: Sailortown is the least conventional in terms of its cartographic character. The piece operates completely detached from a grid, relying on storytelling, listening, and objects to map Sailortown prior to the building of the M2. Therefore, the project stems more from Neuhaus’ LISTEN and Cardiff’s soundwalks; these maps unfold in the experience of listening and navigation through space rather than as visual diagrams. However, their ability to map facets of space, place and existence is no less profound. By stepping away from the gridded map of Belfast, Stories of the City: Sailortown revealed voices that had been silenced in traditional maps of the city.

Even so, it is important to consider whose interests this map serves and the different motives various parties brought to the project. The MAC exhibited a project that engaged with a local community, Fionnuala and I were able to share the artistic work we had created, but what of the SRG? Members of the group have expressed how much pride and fulfillment they have felt in the project, raising Sailortown’s profile in Belfast’s collective consciousness. Many members commented on how good it felt that the people who came to the installation and heard the seven songs were interested in learning about their lives and stories. For example, one of the SRG members, Marie O’Hara, described what it was like to participate in the project overall:

These girls arrived out of the blue and lit up the world for us just by asking us where we came from, how we felt about where we came from, [and] how we lived it day by day.[6]

Songwriting was a powerful medium with which to communicate not only the details of Sailortown and the SRG’s individual histories, but also the emotions that are so strongly connected with these memories. However, the project did not meet with all of the SRG’s expectations. The SRG passionately advocate for more investment in the re-development of Sailortown, and especially for the renovation of St Joseph’s Church. Some members hoped Fionnuala and I could further their cause in some way. Although the project did achieve many things as an artwork and map of the area, it had little influence over Sailortown’s re-development or the renovation of St Joseph’s Church. Therefore, perhaps there was a conflict of interests within this project between mapping Sailortown as an artwork and mapping Sailortown as a political cause, even if the two are not mutually exclusive.

In “Mapping Community Art” (Gielen 2011) Pascal Gielen considers the role of art within the context of community groups and political interests:

Community art only makes sense when it refuses to be used as an instrument of uniform, homogenizing, calculating logic, and when it produces the most divergent communities through the confrontation of many singular and dissonant forms of imaginative power. (Gielen 2011: 33)

We did use the imaginative powers of memory, artistic expression, and cartography to increase public awareness of Sailortown, but we undoubtedly did not, and could never have, physically re-built its streets, buildings, and lives. However, through individual memories, Stories of the City: Sailortown did re-map the area’s “in-between-spaces” of memory, artistic expression, and cartography to increase public awareness.

Conclusion

The examples presented here demonstrate how sound can communicate often overlooked “in-between-spaces” of our surrounding environments. Soundscapes of The Black Hills profiles cartography as artistic medium, while Miastofon requires the user to orientate solely through their listening, exposing alternative methods of navigating Gdańsk. The most un-gridded of these examples is Stories of the City: Sailortown, which places personal memory at the center of its mapping through song, installation, and storytelling. These different approaches to soundmapping provide not only exciting potentials for sound studies and sound art, but also for geography, anthropology, and many other disciplines. All of the projects presented here show that mapping creatively with sound allows new voices to speak up within cartography. Miastofon and Stories of the City: Sailortown especially profile marginalized communities who either navigate a city differently (Miastofon), or remember a city differently (Sailortown).

While gridded soundmaps do indeed play an important role in plotting the aural characteristics of our surrounding environments (human and non-human), mapping the significance of sound requires a more flexible and creative platform. The above examples illustrate that as sound artists, academics, and/or enthusiasts, it is our responsibility to explore the potentials of expanding the boundaries of the gridded soundmap platform. This is not an argument to remove the grid completely from soundmapping. Both Soundscapes of the Black Hills and Miastofon prove there are creative ways of using gridded maps. However, as Stories of the City: Sailortown demonstrates, a grid is not essential in order to map, and it may not always be the most effective and appropriate medium. Therefore, we must be wary of homogenizing listening in the effort to democratize cartography. If we are to truly engage communities with their surrounding environments through sound, we must map the domestic and the private, the personal and the significant, the individual and the overlooked: the significance of sound and its meaning within our listening.

References

Anderson, Isobel and Fionnuala Fagan (2012). “Stories of The City: Sailortown.”

Becker, Carol (2009). Thinking in Place: Art, Action, and Cultural Production. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

British Library (2010). “UK Soundmap.”

Caquard, Sébastien (2013). “Cartography I: Mapping narrative cartography.” Progress in Human Geography 37/1: 135-144.

Cardiff, Janet (1999). The Missing Voice: case study B.

Cardiff, Janet (2000). A Large Slow River.

Cardiff, Janet (2011). Her Long Black Hair.

Cardiff, Janet and George Bures Miller (2011). “Janet Cardiff and George Bures Miller.”

Ceraso, Steph (2010). “The Sight of Sound: Mapping Audio.”

DuBois, R. Luke (2010). A More Perfect Union.

Gielen, Pascal (2011). “Mapping Community Art.” In Pascal Gielen and Paul De Bruyne (eds.), Community Art: The Politics of Trespassing (pp. 15–34). Amsterdam: Valiz.

GrubyPunkt (2014). Miastofon.

Harmon, Katherin (2004). You Are Here: Personal Geographies and Other Maps of the Imagination. New York: Princetown Architectural Press.

Harvey, Philip D. (1991). Medieval Maps. London: The British Library.

Heuson, Jennifer (2009). Soundscapes of the Black Hills.

Heuson, Jennifer (2011). “Hearing the Hills: An Acoustic Encounter with South Dakota’s Black Hills.” Sensate Journal 3.

Lane, Cathy and Angus Carlyle (2013). In The Field. Axminster: Uniformbooks.

Limerick Soundscapes (2014).

Long, Richard (n.d.). “Richard Long Official Website.”

MacFarlane, Robert (2003). Mountains of the Mind. London: Granta Books.

MacFarlane, Robert (2007). The Wild Places. London: Granta Books.

MacFarlane, Robert (2012). The Old Ways. London: Hamish Hamilton.

Morris, Leslie (2001). “The Sound of Memory.” Blackwell Publishing on Behalf of the American Association of Teachers of German 74/4: 368–378.

Murphy, Edna, Henry J. Rice and Craig Meskell (2006). "Environmental noise prediction, noise mapping and GIS integration : the case of inner Dublin, Ireland." Paper presented at the 8th International Transport Noise and Vibration Symposium, St. Petersburg.

Neuhaus, Max (2004). LISTEN.

Ouzounian, Gascia (2014). “Acoustic Mapping.” In Matthew Gandy and BJ Nelson (eds.), The Acoustic City (pp. 164–173). Berlin: JOVIS Verlag.

Pinder, David (2001). “Ghostly Footsteps: Voices, Memories and Walks in the City.” Cultural Geographies 8/1: 1–19.

Ramanujan, Krishna (2010). “Acoustic maps of ocean noise reveal how shipping traffic affects whales.”

Stanza (2004). Soundcities.

Waldock, Jacqueline (2011). “SOUNDMAPPING: Critiques And Reflections On This New Publicly Engaging Medium.” The Journal of Sonic Studies 1.

Wood, Denis (1992). The Power of Maps. New York: The Guildford Press.

Wood, Denis (2010). Everything Sings: Maps for a Narrative Atlas. Los Angeles: siglio.