This section documents our transition from a stereo to a spatial sound approach, detailing changes in song structure, vocal treatment, and instrumental arrangement. We present existing strategies, describe our methods, and outline the outcomes. The focus is on how spatialization has been integrated into composition, performance, and notation.

We developed ways to build open-form sections into our song structures, often appearing as intros, instrumentals, or outros. These are created through improvisational systems we call “universes,” which are built from samples of our existing recordings. These samples can be reprocessed live with effects and spatialization, forming layers and loops of vocals, field recordings, percussion, and other elements. These universes also act as transitions or segues between songs—spaces that can be improvised and manipulated in real time.

We explore a range of vocal configurations, alternating between solo and duet lead vocals (narrators), and integrating polyphonic, pitched, and fragmented vocals. These processed elements often transcend traditional vocal roles and become part of the instrumental or ambient layers of the composition.

We have developed interfaces that allow us to manipulate the position and movement of our voices in space. Our toolkit of vocal processing effects has expanded, enabling more nuanced expressions. We have also been experimenting with vocal hierarchies and role switching, such as toggling between leading and supporting roles within a musical piece, and between simplicity and multiplicity in the narrative (e.g. in the song Sweet Spot).

Our mixing strategies often position the lead vocal, the main narrator, as an omnipresent anchor. By contrast, cut-up and polyphonic vocal fragments form an ephemeral ambient layer. We found that these layers show strong potential when combined with movement and spatial effects to create immersive environments, both compositionally and in performance, when live spatializing.

This ambient layer can act as a spectral double of the lead voice, like an “evil twin”—processed, doubled, and given its own spatial trajectory. These explorations open up rich thematic territory, touching on heritage, identity, generational dialogue, and personal reflection.

We also investigate agencies: Who controls the voice? Do I direct the processing and spatial trajectory of my own voice or that of my sister’s? What if I’m manipulating the voice of her double, or my own spectral twin?

We mixed predefined spatial arrangements with real-time improvisation using spatial interfaces, enabling live control of position, motion, and effects in sync with each track. The core elements, such as beat and bass, remain grounded, while spatialized layers—percussion, effects, pads, and synthesizers—move dynamically to create contrast and depth. Echotails, animated percussion, and varying spatial treatments enhance the atmosphere. Inspired by cinematic sound design, we use spatial trajectories to position sounds in 3D space, such as thunder panning across the room for a more visceral experience. Our spatial sound design combines earthly with otherworldly environments of texture and motion.

Example of mixing omnipresent elements, such as bassdrum, snare, and lead vocals, with more ambient and spatially dynamic elements, including fragments of sound design, swirling chorus vocal effects, and delays on the snare—all live spatialized with our spatialization interface prototypes. It is also an example of live vocal processing/pitching the voice with formant shifting. 3daysofdesign, 2024

Like any compositional tool, spatial sound relies on balance, contrast, buildup, and release. Spatial sound encourages the ear to travel, focus, and explore. To preserve clarity and avoid auditory clutter, we typically limit ourselves to two or three primary spatial gestures at any given time. Too much movement can muddy the experience; the ear can track only so much. Low-end frequencies do not lend themselves well to spatial motion, as their directional cues are more difficult for the human ear to detect, so we often leave them grounded.

In a binaural recording of the song Peace of Mind from a listening session at DKDM (2022), we experimented with spectral mixing (the flute above and low bass below), with swirling vocals in the chorus, omnipresent beat, cello and narrator/lead vocals, and more dynamic sound design elements, such as thunder and other sonic textures in individually programmed trajectories.

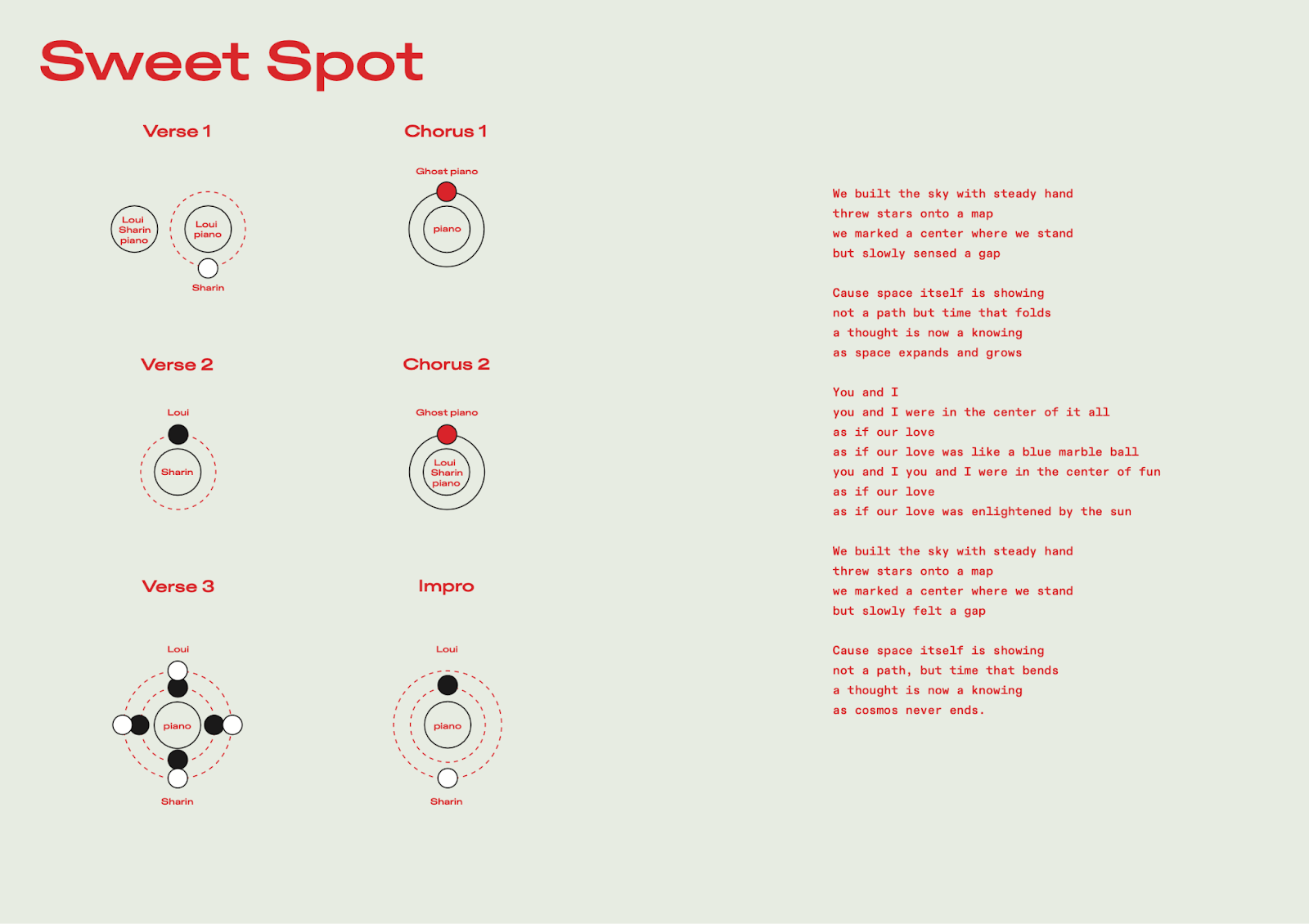

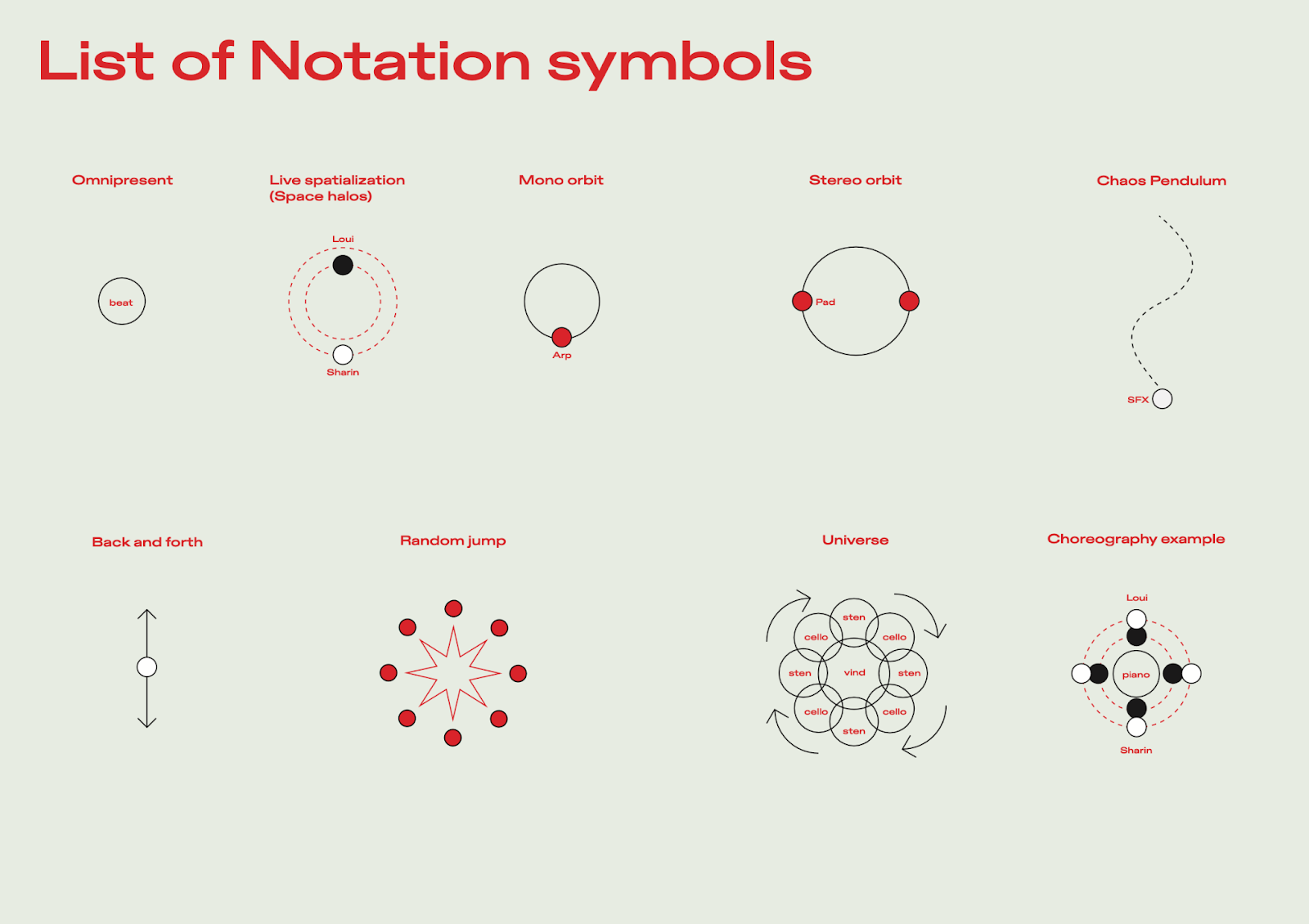

After an iterative process, we have arrived at a notation system that we use to map spatial arrangements and strategies for our songs (find more examples of songs in their final version in the Spatial Scores section). While working on the song Sweet Spot, the notation system prompted conceptualizing spatial ideas and choreography visually before implementing them sonically.

The notation system is useful in choreographing spatial gestures, movements, and relations between voices and instruments, and in mapping the different spatial strategies related to different segments of the songs.

We mapped the interface used and different types of movements, such as “back and forth” or “random jump,” and “mono” or “stereo orbits.” We mapped live spatializations and predefined paths (unbroken or dashed line). We also mapped specific choreographies and “universes” along with their file names for easy access to files in Ableton. In addition, we mapped when sounds were omnipresent.