As part of VSS, we have been building our own sound controllers (MIDI interfaces). In this part of the exposition, we elaborate on that decision and reflect on how this DIY approach has been both fruitful and, at times, counterproductive for SØSTR. The arrangement of sound in space is widely considered important in music creation. However, there has been comparatively less focus on tools and practices for live spatialization (Pysiewicz & Weinzierl, 2017).

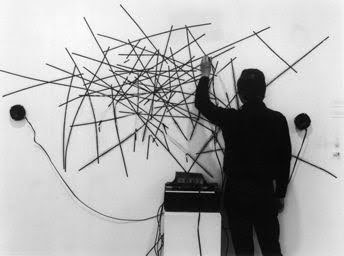

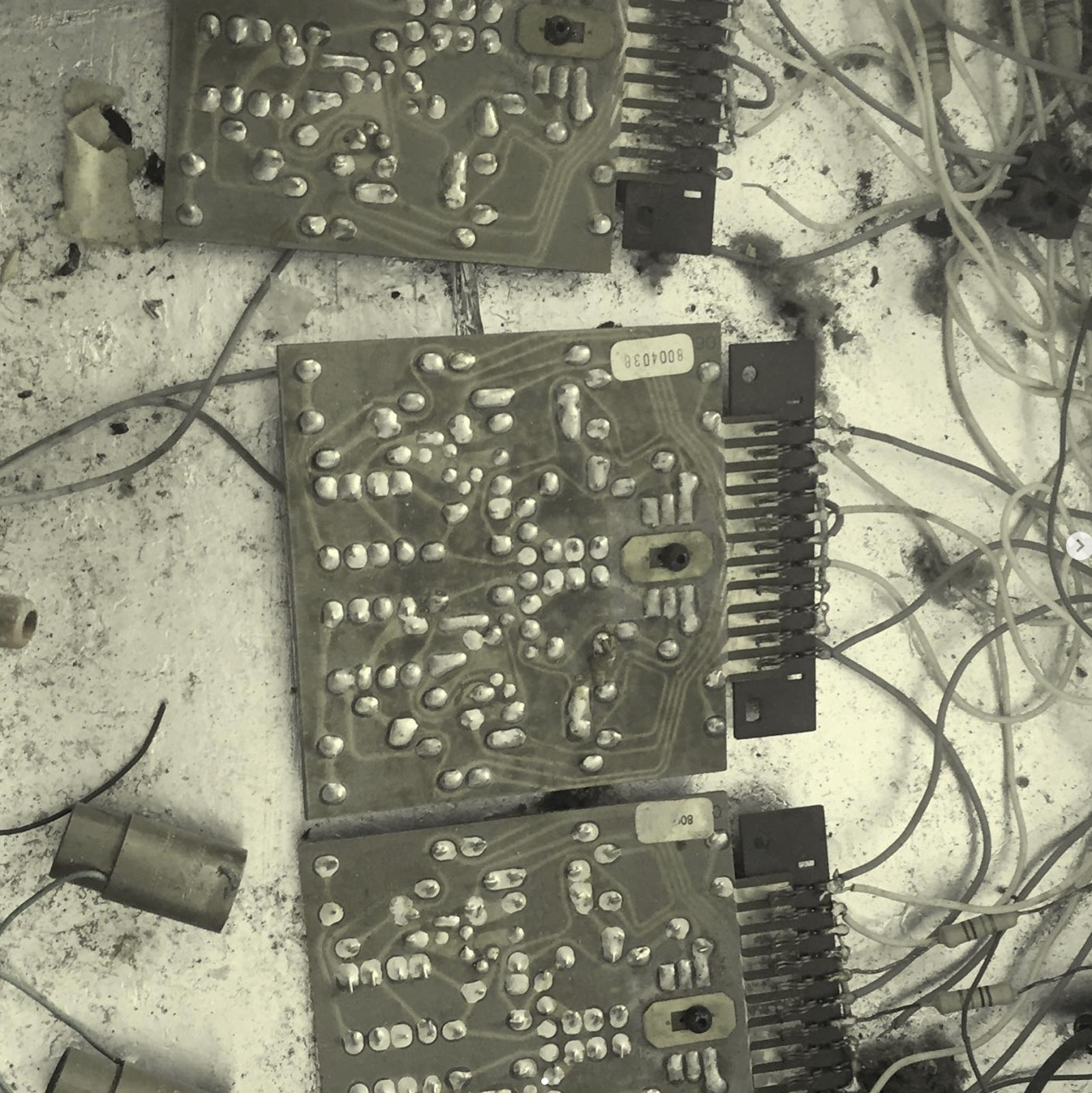

Our custom interfaces have helped us rethink sound and develop new approaches to spatialization in a way that is embodied. However, the time and effort spent troubleshooting technical issues have often been excruciating. The systems we have built are not especially stable or portable, posing further challenges when performing in different environments.

Louise is an alum of the interactive telecommunications graduate program at New York University, where she took the subject NIME: New Interfaces for Musical Expression. In recent years, at the RMC, she has been teaching her own versions of interface design as elective courses, such as MENI: Musical Expression for New Interfaces, a course inspired by NIME but with an emphasis on compositional strategies and co-taught by Halfdan Hauch Jensen, Lab Manager at ITU’s AIR Lab. Another example is Composer as Designer, which is co-taught by robotics engineer Hjalte Hjort.

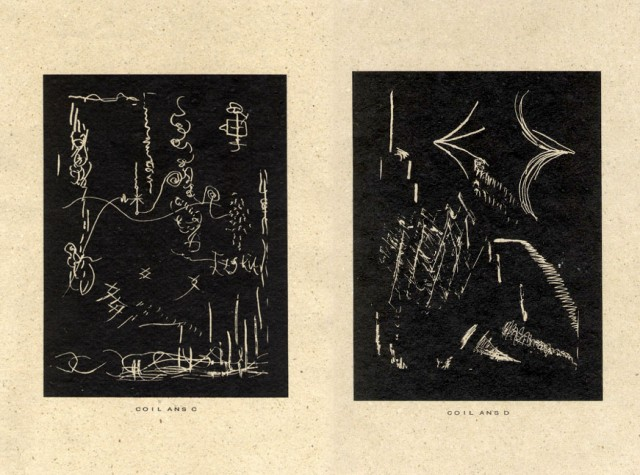

These courses and the ideas, approaches, and student work that emerged from them have directly influenced VSS. The work developed in these classes challenges the limitations of conventional MIDI controllers, including keyboards, knobs, and faders, and encourages alternative ways of interacting with sound. Student projects have involved triggering sounds through brainwave activity, light, heat, the conductivity of human skin, and interactions with plants and body movements through space.

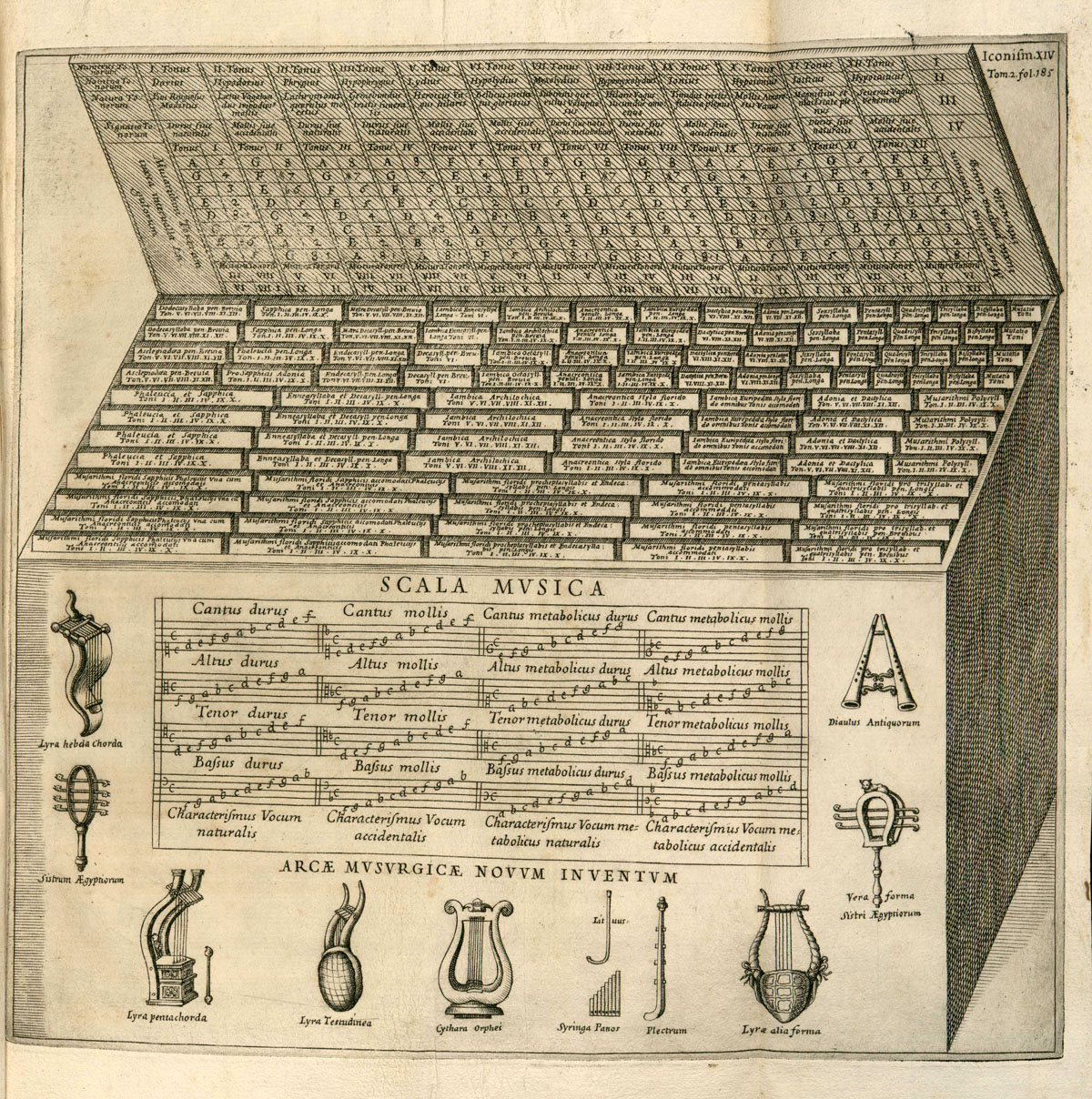

Our interface designs are also inspired by a series of historical inventions (listed at the end of this page). Each example reflects a shared ethos: offering performers a different kind of control that is tactile, exploratory, and embodied. We aimed to create a setup that is less about mastering an instrument through repetition and muscle memory, and more about creating an embodied experience of sound through exploratory objects. This approach opens up performances to those without traditional musical training, enabling them to learn how to play not in the conventional sense but by engaging directly with the object.

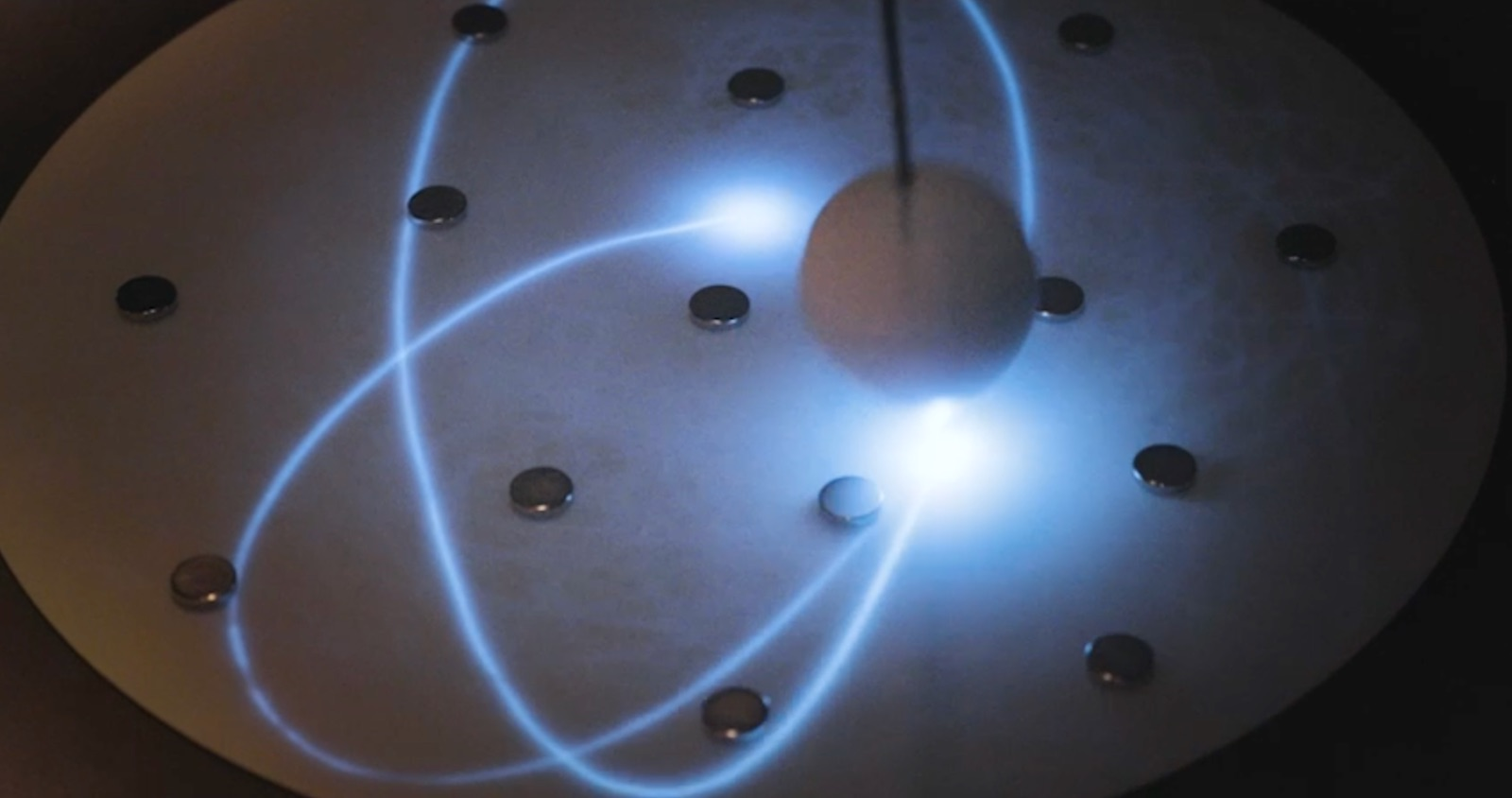

We approached the design of the SØSTR interface setup through engagement with spatialization software. In most cases, the sound source is represented by a sphere moving in a virtual space. This inspired us to explore the idea of moving sound sources physically as tactile objects in real space. Once we identified this as our goal, we began investigating the kinds of trajectories these sounds could follow through prototyping and an iterative design process. This led to the creation of the Space Halo, Bagua, and Chaos Pendulum. The design process for each interface is elaborated in more detail elsewhere in this exposition.

While our goal was to create embodied, experiential interactions with these objects, we are still musicians searching for musical outcomes. Like spatialization itself, these interfaces are new to us. We are still learning how to hold the spheres and pendulum, how to perform with them, and how to listen to what they can do.

DIY sound control is not only about designing our own tools but also a way of shaping our performative identity. It is about redefining access, authorship, presence, and focus in performance. Designing your own controller becomes a way of designing your own way of sounding.

Overall, we developed a system that allows for both precise control over the position of sound sources and the incorporation of more chaotic trajectories, enabling performances that explore the tension between order and chaos.

In this explorative process, new questions constantly arise. One central question we continue to grapple with is “Do we limit sonic possibilities by ‘encapsulating’ sound sources as singular visual points in space?” or “Do we create an engaging tension between the ‘frozen,’ objectified sound and the sound that is quite literally out of our hands, as it scatters, traverses, and multiplies?

Reference

- Pysiewicz, A., Weinzierl, S. (2017). Instruments for Spatial Sound Control in Real Time Music Performances. A Review. In: Bovermann, T., de Campo, A., Egermann, H., Hardjowirogo, SI., Weinzierl, S. (eds) Musical Instruments in the 21st Century. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2951-6_18