The first ordinary story I collected (click on the image to read it.) is Jacopo’s, a friend who shared with me his relationship with his photographic memories, memories that have everything to do with the act of collecting. Although the collection he tells us about has not undergone any act of editing (but lives on an indiscriminate accumulation), however, chance wanted that his biological father’s

presence has been collected so briefly that of him last only a few photos out of more than a thousand. As much as we try to collect ‘fields of reality’ in an exhaustive, objective and methodical way, our gaze will always tell a partial story.

As the authors Daniela Ferrari and Andrea Pinotti highlight in the introduction to the book La Cornice, storie, filosofie, testi (The Frame, stories, theories, texts), which analyses the role of the frame within pictorial representation, the “frame determines a field, delimits our gaze and protects, determines the necessity [...]. The act of photographing is in itself an act of collection in which we decide which aspects of what surrounds us to collect and above all which to exclude”.

The structural foundation of photography is precisely the fact that the more it entangles us in its likelihood with reality, the more we distance ourselves from the awareness that outside its edges there is a world to which we have no access and that without a context, without a narrative, this world is unknown to us.

The album-object, a ‘summary’ from the moment of its composition, accepts its continuous incompleteness and its constant updating in order to exist.

After taking a photograph, then, what act of collection is performed when the album is composed? And again: if the album is in itself a frame, what do we decide to include and what to exclude?

Right at the beginning of my research, I stumbled upon a beautiful book (P. Genard P. and A. Barret, Lumière, les premières photographies en couleurs, Trésors de la photographie, André Barret éditeur 125, Paris 1974 ) that tells a little-known but very significant story: the Lumière brothers, remembered above all for their pioneering contribution to cinema, innovated the world of photography through an invention (by their own admission the most precious of all) for which they are less known: the Autochrome Lumière (patented in 1904), an invention that propelled photography in colors into the future.

The striking element for me, though, is for me the fact that at the moment of one of the greatest technical innovations in photography, the two brothers chose to point the camera towards the small world of their everyday life, using themselves as the subject by opening an intimate window onto their world, portraying themselves in ordinary, private moment. With an extraordinary invention that brings us even closer to the illusion of capturing reality, the two inventors did not immortalize a great event or a famous person (as we might imagine a great invention could be used and as it was actually used shortly after!), they did not decide to give the first Autochrome portrait in history to a king or a queen: they had fun portraying their own private universe. Maybe they didn’t give too much importance to their favorite child but used it as the extension of themselves. With the most cutting-edge instrument in the world they collected the thing that was simply closest to their hearts, what Christian Boltanski would call the little memory, collecting, perhaps, the first color family album in history.

I then analyzed Sentimental Journey 1971-2017 by Nobuyoshi Araki, who over four decades collected images of his muse, his wife Yoko, not stopping even after her death, searching for a trace of her precisely in her absence, in the void filled by the objects she touched. Toward the end of the journey, the lens focus on their cat, and it's almost as if it somehow took the woman's place, revealing the game of interpretation that underlies the photographic action.

The image, therefore, simultaneously takes into account the eye of the photograph and the eye of the person experiencing the result of that gaze, creating an empathic connection between the two visions, a bond that allows them to transcend time and space. The portion of time and space represented, in fact, inevitably provokes questions in the observer’s mind about what surrounds the representation, what comes before and what comes after, what is not framed, as well as the value and motivation behind what is seen: we end up looking for the features of ours beloved who are no longer here even in the branches of a tree stretching in the sky.

Photographer Liliana Barchiesi has published a very interesting book titled Donne è Bello (Women is Beautiful), Edizioni Postcart srl, Rome 2020. In a post-'68 Italy where the feminist subtext is highly relevant, she enters the homes of a series of women with her camera and, with sharp irony and subtle social criticism, investigates the role of women in the family. It is a collection of images that portray the home as the "realm of women" in a time when the role of women was being called into question thanks to feminist struggles. The series of photographs Barchiesi creates appear as portraits worthy of a place in the family album: what place is more intimate and distinctive for a woman than the home? Here the author plays the dual role of itinerant photographer and (very) aware witness of her own era, provocative without letting it be noticed, and puts photography at the service of sociopolitical discourses criticizing patriarchy: just as family rituals are immortalized and displayed in albums, the portrait with the household appliance makes the woman the protagonist of a new contemporary ritual, being the 'queen of the home' in a patriarchal world precisely at the moment in which it is being dismantled.

I then examined another book, a sort of album of ugly images, which tells the life of photographer Richard Billingham's family: in an anti-photo album, the author has collected aspects of his father without sugarcoating it (as often happens in family narratives), even exhibiting it without shame. Richard Billingham lives with his parents amidst poverty and deals his father's alcoholism in a council flat in Cradley Heath in the Black Country, a coal-mining area west of Birmingham, in the English Midlands. Here, while studying painting at Bournville College, he began to point the lens of his first camera at his father Ray with the sole purpose of creating models for his pictorial studies. Soon, however, the photographs took over: "The photos themselves seemed more and more real to me."

Rather than being a collection of smiles, his photographs bear witness to the illness, violence and ugliness of his own daily life, suggesting how this reality can unfold within any home. We are the witness of the "wrong" moments that at first glance leave us doubting their intentionality, but which in reality conceal authentic Bressonian "decisive moments." With obsessive precision and method, Billingham hunts for these embarrassing, "ugly," and even cruel moments, exposing what happened within the four walls of the homes of countless English working-class families. Precisely through this collection of superficially grotesque and degrading snapshots, the author's parents appear as two anti-heroes, protagonists of a social tragedy—as indeed it truly is.

Usually in a family album we put our "best" photographs, the "good" moments, so much so that it seems as if all those smiling people have never had a bad day in their lives. We know this cannot be the truth. So when Billingham's anti-album forces us to admit that behind the facade of perpetual happiness, harmony, and contentment we construct for ourselves, there is discomfort, flaws, sadness, and desperation, we can talk about a photographic revolution. It's obvious that Richard Billingham's family also had happy moments, but the way they are collected and recounted, only the moments the photographer chose to photograph survive in the legend of Ray and Liz.

In The Fury of Images, a key text for my research, Joan Fontcuberta writes about how the first photo albums appeared in bourgeois circles in the second half of the nineteenth century and how they were an intergenerational project, arranged in a vague chronological order, beginning with visiting cards and other portraits taken in professional studios, with the stated purpose of passing on a beautiful story.

Contemporary postmodern society has disrupted this concept thanks to social media, a public space where intimacy is put on display, family photographs are exhibited, and even death is the object of spectacular attention: "We are witnessing a sort of decline of affection”, Fontcuberta writes, in a world where the social and private spheres no longer have rigid but fluctuating boundaries, distances have become dizzyingly short, and the very concept of identity takes on new meanings. Visual diaries and reportages explore the intimate lives of individuals or social groups, subverting the concept of the private album and becoming a source of information and emotional engagement.

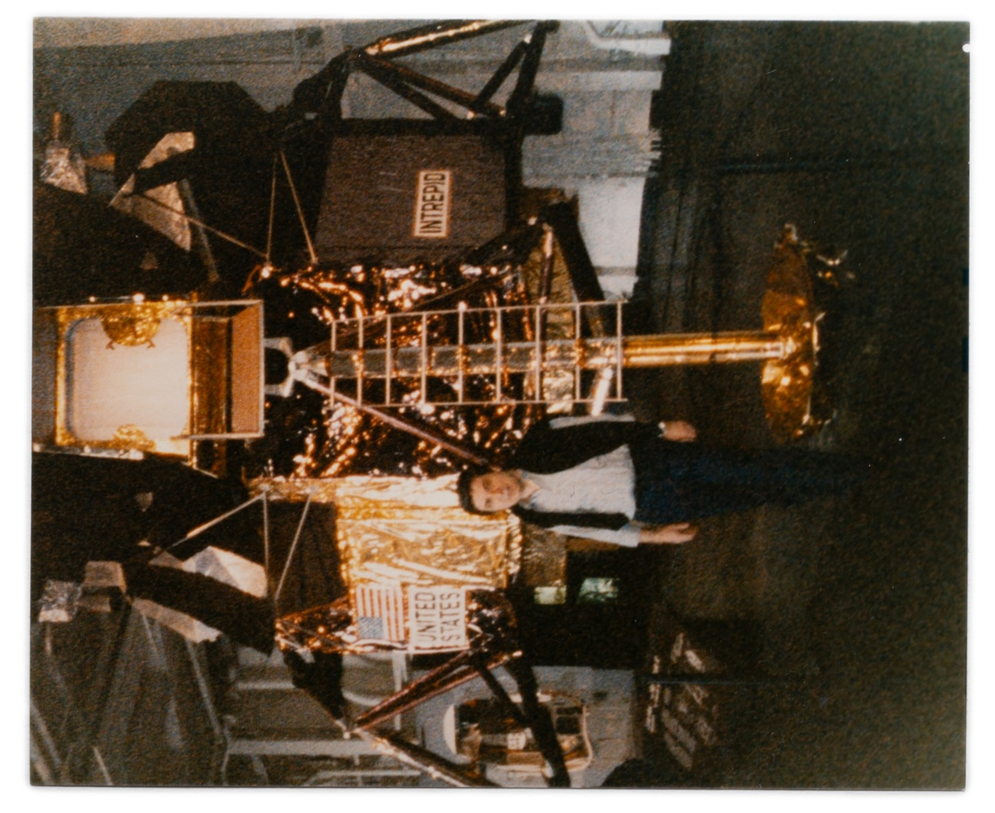

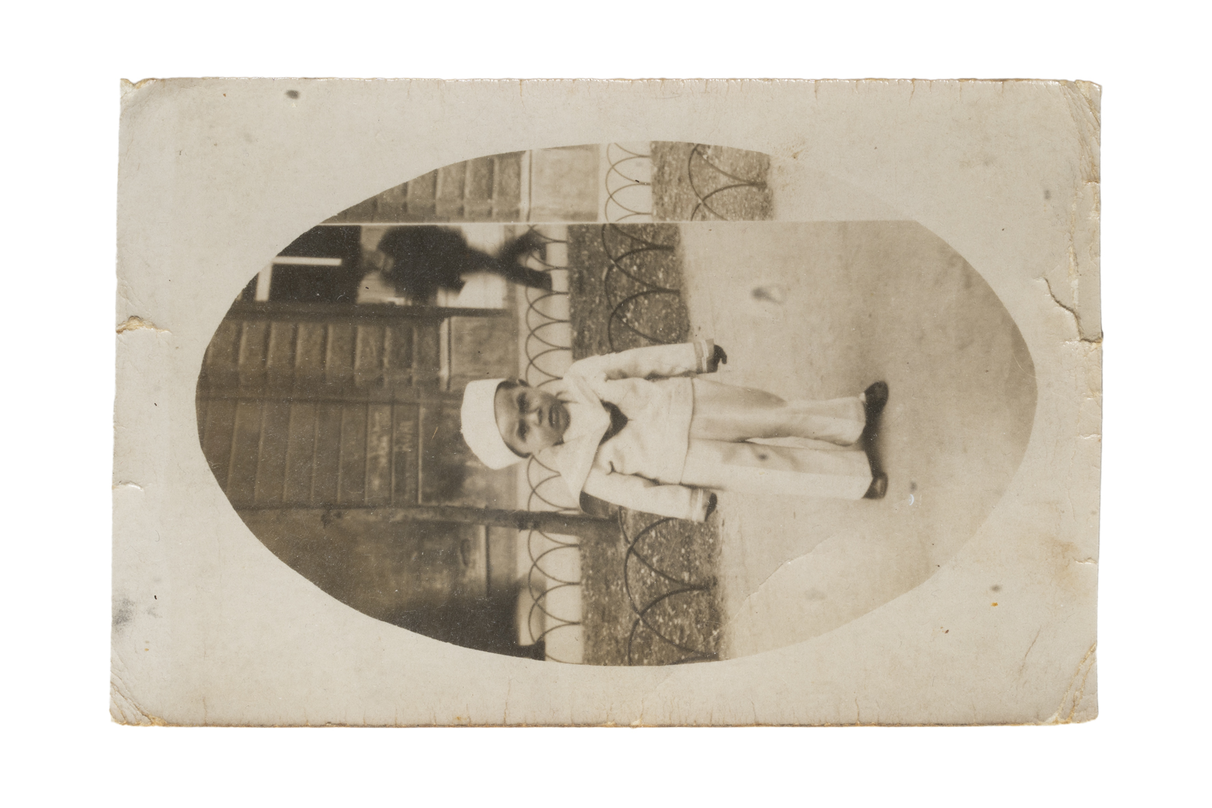

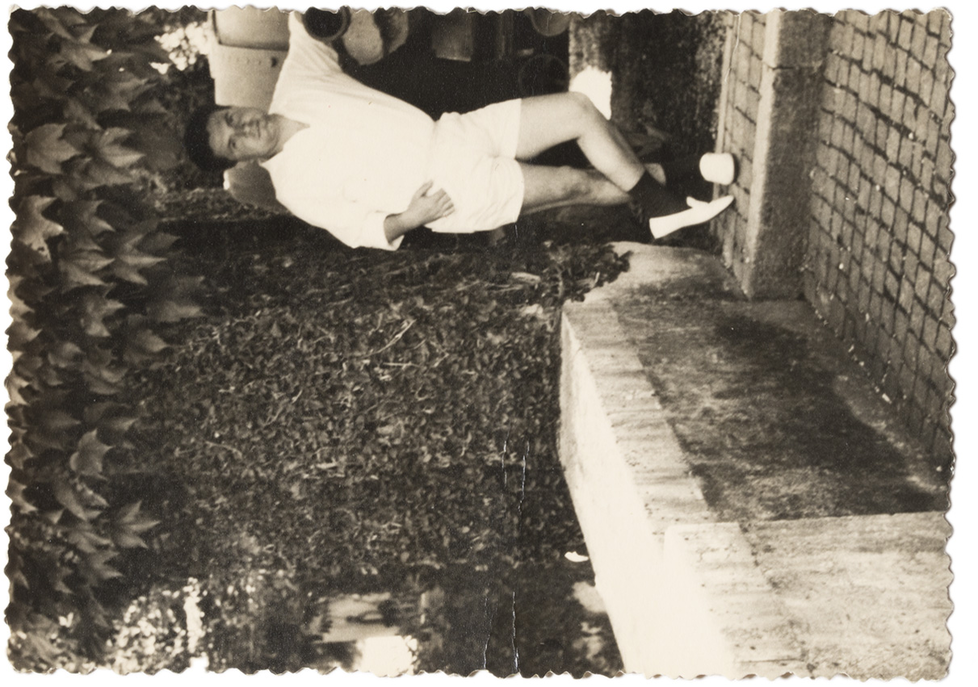

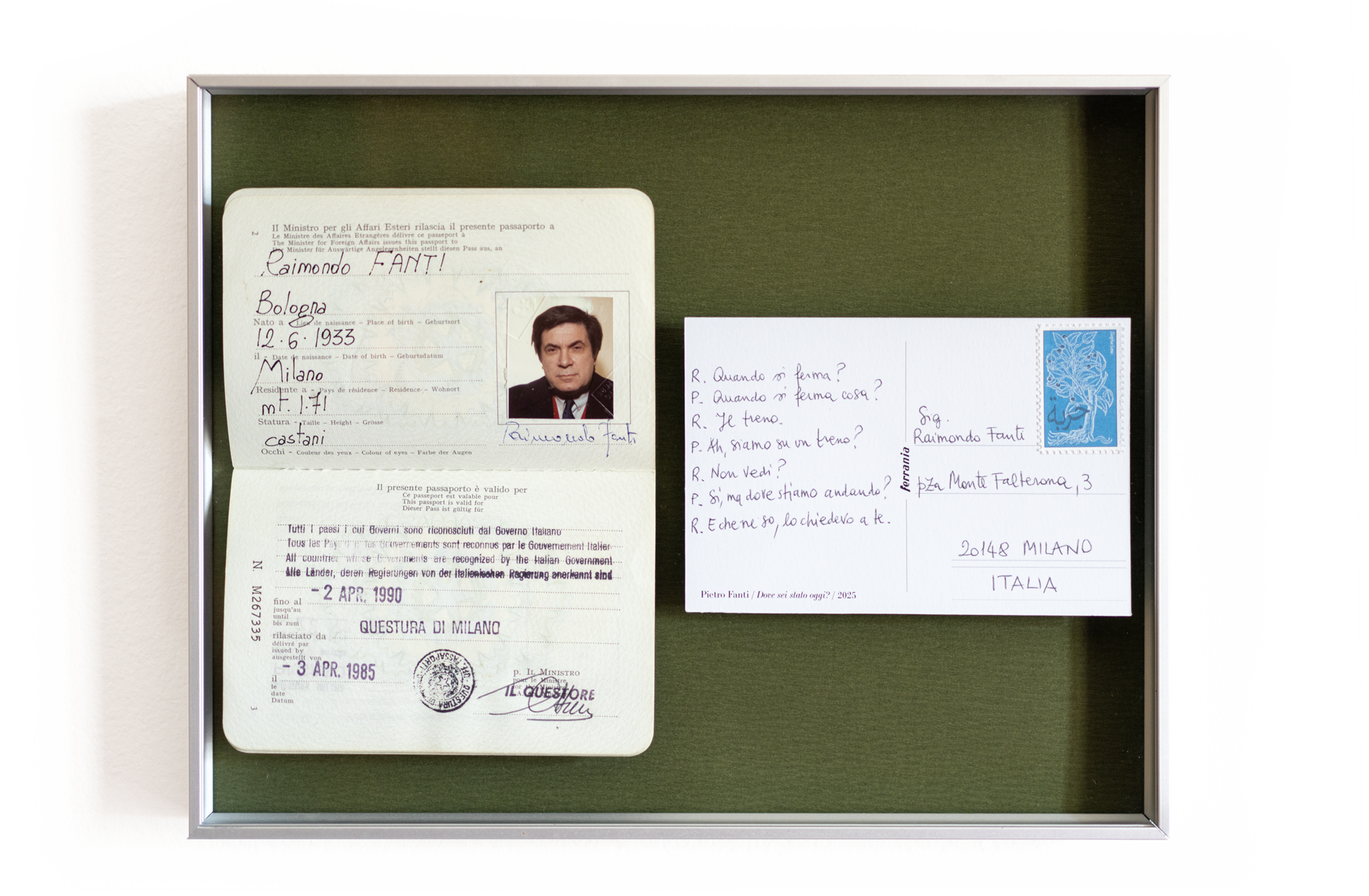

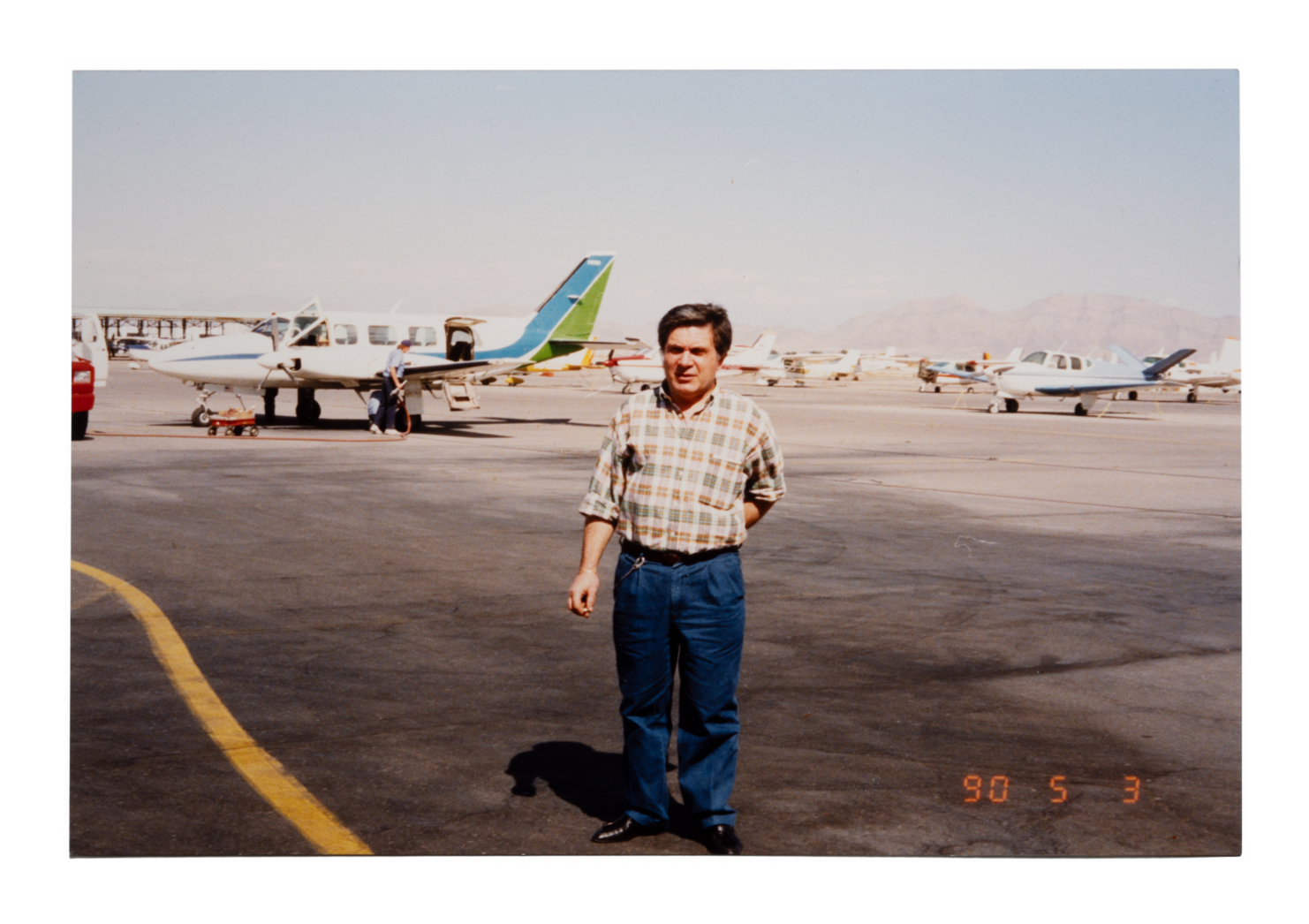

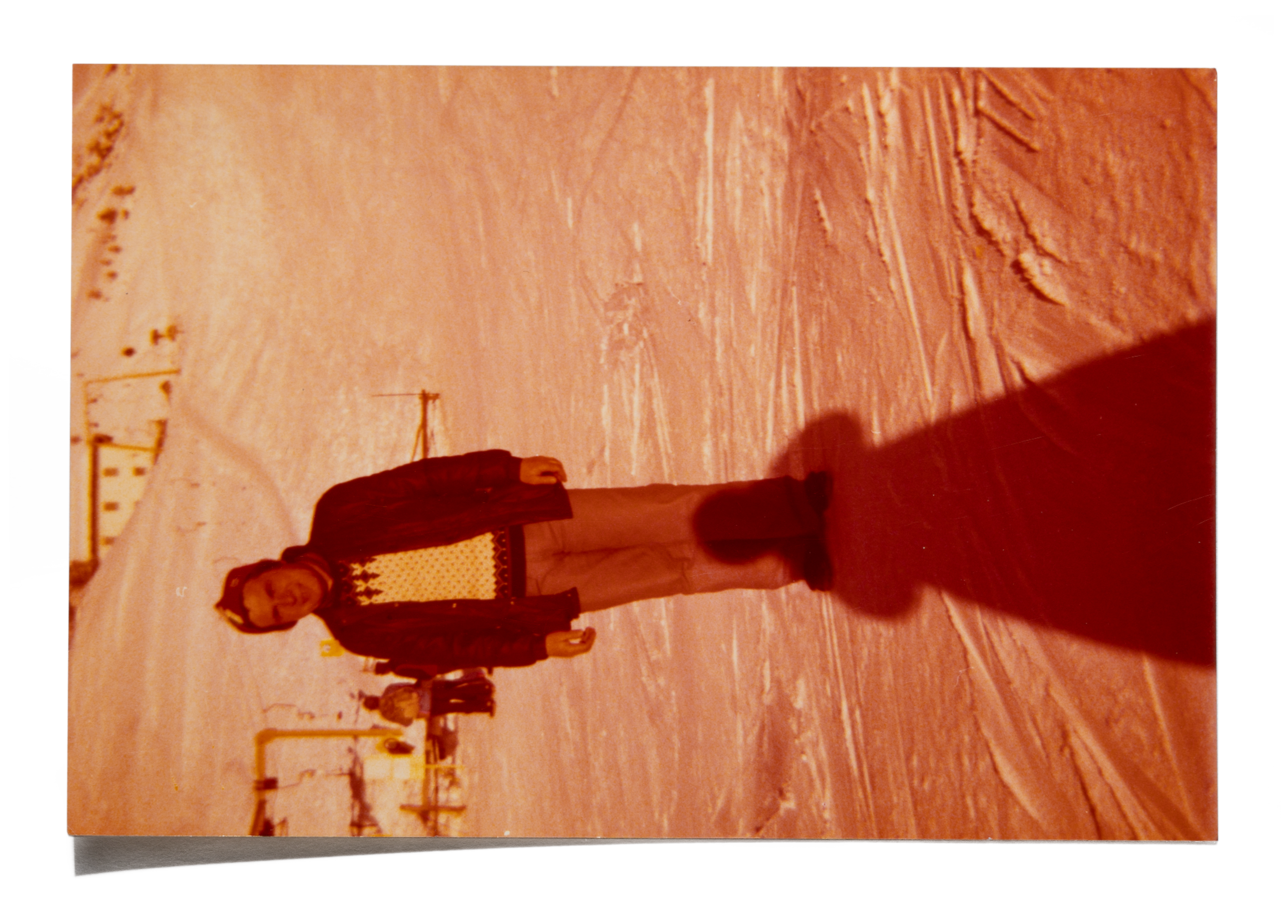

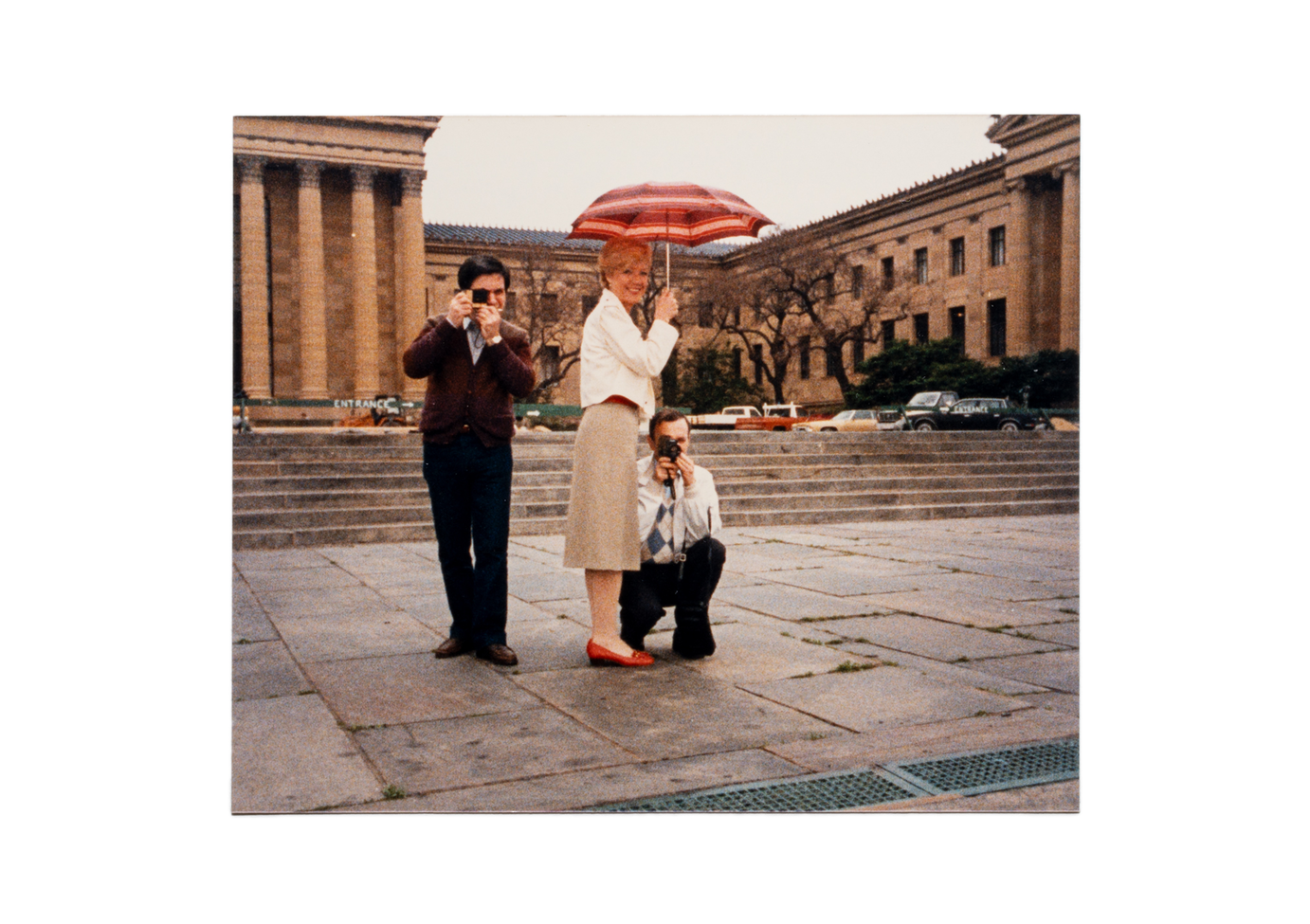

The family photographs my grandfather Ray collected are all gathered together in a disorder limited only by the briefcase where they were locked so as not to be lost: photos of himself during his many travels, photos of weddings, confirmations, memorial photos from a funeral, letters of condolence after the death of his wife, Grandma Emilia, along with those of his newborn and gradually older grandchildren.

I'm struck by the fact that Ray's album wasn't fixed in a restrictive place but rather stored in a travel bag: the sense of himself in motion was transferred to his traveling album, and it is out of respect for this attitude that they have logically become postcards awaiting departure for a new journey.

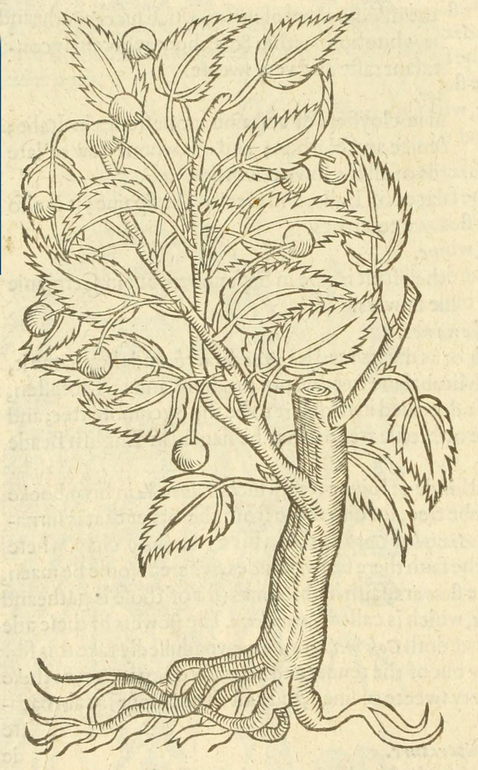

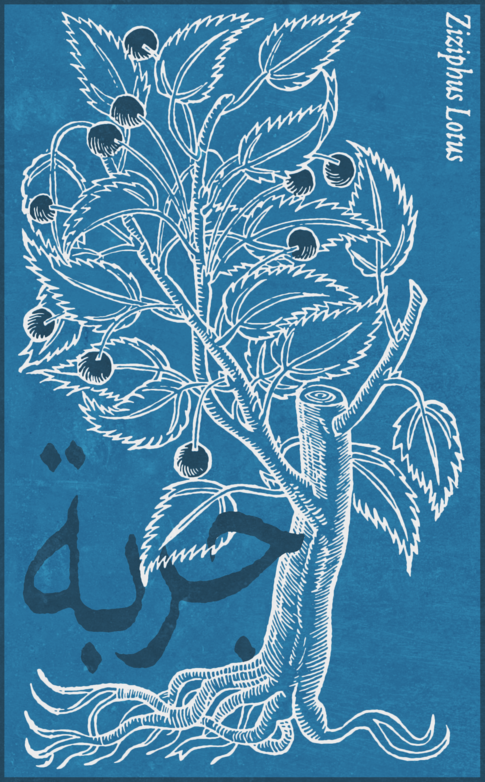

Stages of creation of the stamp, based on the engraving of the Ziziphus Lotus found in the Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes, by John Gerard

(Where have you been today?) I was in Switzerland with you, can't you remember? 2023, Photography, inkjet fine art print, 60x100x4,5 cm

In December 2023 Raymond passed away, but this did not stop the research from evolving and indeed gave it an unexpected twist. While emptying and documenting his house I found a briefcase containing 254 photographs kept messily together alongside many documents that testified to his past, his story since his early childhood and, above all, the real life trips he had made during his life.

Their lack of context, by never having been organized in an album and now by not having anyone anymore to give them any, granted the pictures a sense of both anonymity and vibrant potential.

I decided to scan all the photographs and give them a new role: they too had to leave for a new journey. The emblematic form in which a photograph has always physically traveled is the postcard, just like the ones Raymond had always sent from his vacations.

The stamp I then designed serves as a common thread that unites all of Raymond's travels, both dreamlike and real: for its iconography I started from the IXth book of the Odyssey (verses 82-102), a passage that tells how Ulysses comes across and gets lost on the island of the Lotus-eaters, who give him the mysterious fruit that makes him lose his memory of home. There is no certain source about which fruit Homer was referring to, since what we recognize as the lotus does not produce fruit, so I relied on modern interpretations that led back to the sweet fruit of the jujube tree. I then looked for the first iconographic appearance of the jujube tree, finding it in the book The Herball or Generall historie of plantes by John Gerard (1545-1612) that was first published in London in 1597, where there seems to be the first illustration of the plant. The same interpretations argue that the island of the Lotus-eaters is all but an island: located on the coast of Tunisia, it should correspond to the modern city of Djerba. I therefore contextualized the language and provenience of the stamp, imagining it to be Tunisian and written in Arabic. The 254 postcards were then placed in a revolving display and I finally framed Raymond's passport next to one of his postcards, ready to be sent.

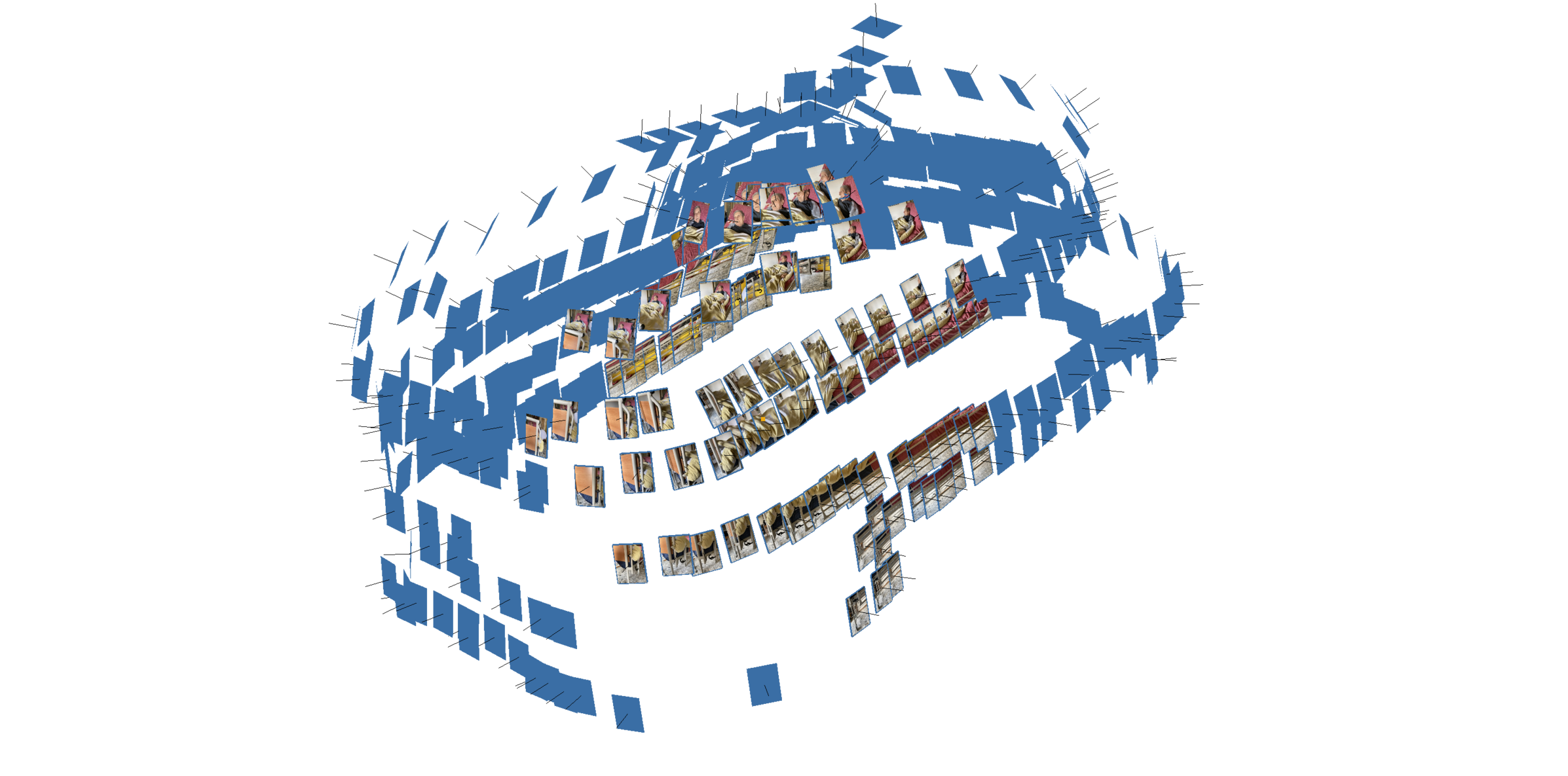

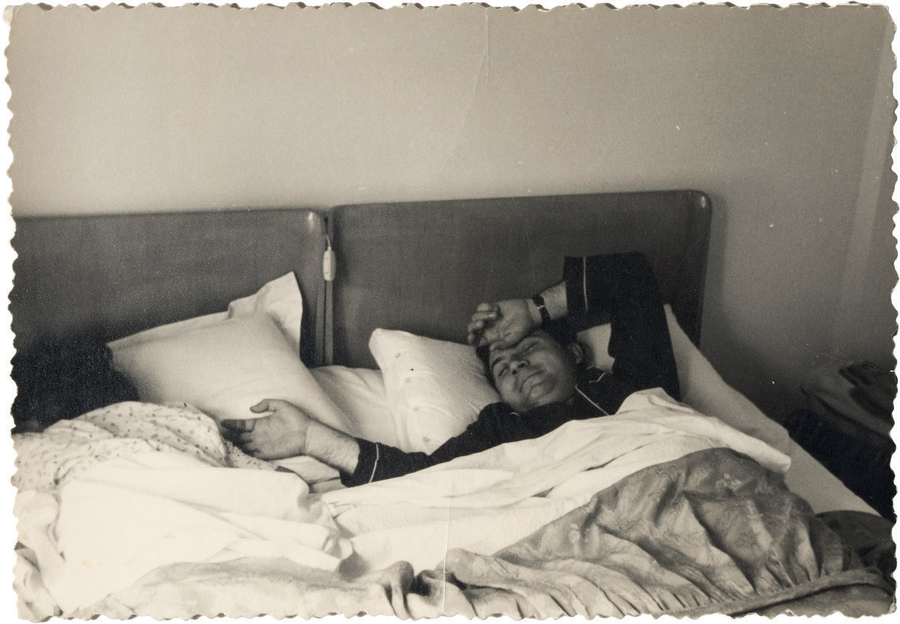

Even though I couldn't physically move the bed where Raymond was sleeping, I wanted at all costs to take him to the places he thought he had travelled to. In my previous projects, I had been fascinated by the use of photogrammetry, a technique of 3D synthesis that uses a multitude of photographs of a single subject taken at multiple angles an distances. These images are then to be analyzed in sequence and aligned according to their matching points.

From the first experiments, I understood that I was on the right path: although it is possible to achieve totally photorealistic results, I preferred to maintain a level of artificiality in the resulting 3D model by simply taking fewer photographs (for a subject the size of the bed, some thousand photographs would have been needed. I took less than 500).

My goal was never to fully deceive the viewer, but only to trick their eyes at a superficial level: I wanted them to wonder how a hospital bed could have ended up in such incongruent places and then, upon a second glance, for them to clearly realize that the subject did not belong to that photographic reality at all. This was to create a further narrative level caused by the visual mismatch: the lack of sufficient information results in a rough surface full of missing parts introduced into a meticulously detailed landscape.

The programs I used in this synthesis phase were mainly Agisoft Metashape and Blender. Once our subject had been acquired, for each of the photographs that make up the series it was essential to acquire a 360° HDRI (High Dynamic Range Image). This would then be important to be able to immerse the 3D model in the same light as each photographic environment. Through FSpy I created the perspective coordinates for each photograph that would then be used by Blender to insert the 3D object in a credible way within the two-dimensional environment.

Raymond's sentences varied both in quality and quantity and consequently the images - some more than others - needed my interpretation.

Although there is an explicit reference to the digital world throughout the series, I immediately imagined that the final form of these photographs was to be printed in large format to favor both immersion within the settings and the game of recognizing the inaccuracy of the digital artifact.

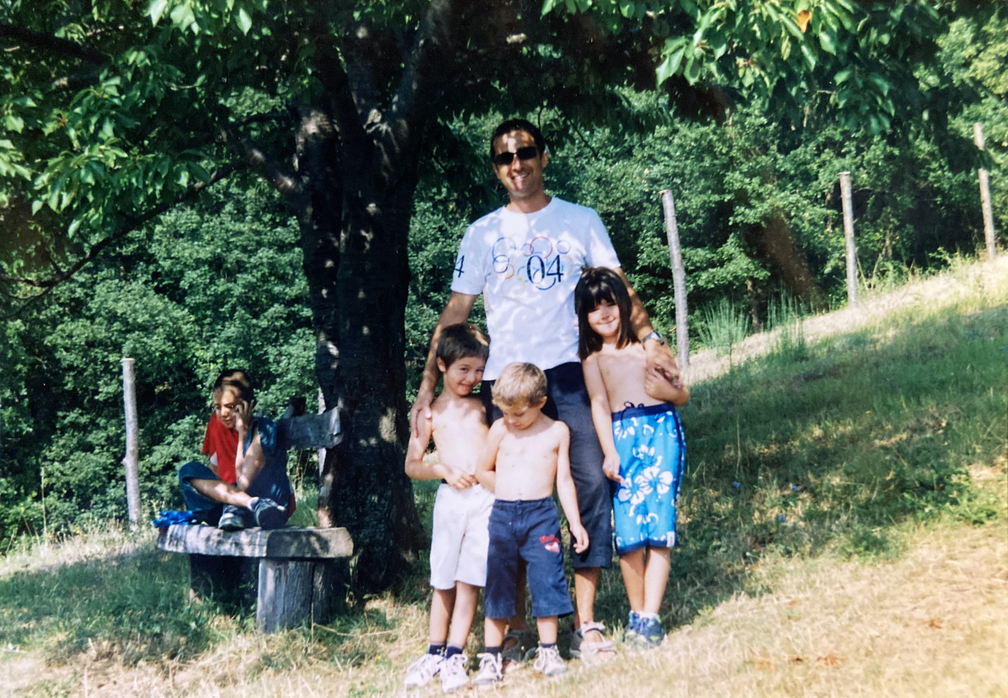

This project began in 2020 when my grandfather Raymond showed the first signs of dementia. The isolation due to the prolonged pandemic lockdown pushed him into in an increasingly smaller psychological space and in a painfully short time he lost his physical and mental autonomy. It was at this point that he was forced to come and live with me and my family.

The person I once knew, independent and extroverted, in the span of a few months gently dozed off as if immersed in a new inaccessible reality. Where was he going when closed his eyes? I couldn't know. There were days, however, during which Raymond regained a state of partial conscious wakefulness and in those moments he opened a small window for me to peek into his perceptions and thoughts: I thus discovered the places where he thought he had been and the multiple journeys from which he always seemed to return.

I began to keep a diary of our daily ritual: every time I returned home he was surprised to see me again, as if I had come back after a long time: "Where have you been?" He would ask. I then tried to ask him the same question: "Where have you been today?" The answers drew mainly from the memory of his past: days at work, meetings with people who had passed away decades ago, distant places he had visited once in his life; however, there was also the attempt to adapt to the present and feel integrated into the reality of the family. "I was there too, I was with you!" he exclaimed once, when I told him where I had been. "Don't you remember?”. This was the third part of his reality, the one populated by fantasies, nightmares and surreal events.

I wanted to give a form to Ray's new reality and I realized, in the process, that ultimately, there was nothing that made it less "real" than mine. Perception is an individual condition, even the one coming from subjects in perfect health.

As my accounts of Raymond's imaginary journeys began to accumulate, I thought about how to translate these visions into photographs.

Is the family album a real document?

Now it's time to take a step further, that is, to dive deeper into the role of the photographic act in the family memory: what do we choose to remember? Don't we often - either consciously or not - create parallel realities for ourselves, not unlike Raymond? What do we forget or leave aside? How does the creation of a photo album influence the story of our existence and the way in which this story is passed down to the next generation?

To try and get closer to an answer I want to analyze both the work of recognized authors and the micro-testimony of ordinary life of three unknown people interviewed by me to make an example out of it: the artist and the amateur both have the responsibility to frame, collect, group, catalog in sequences, edit according to personal tastes, eliminate or omit elements, up to manipulating the images, being that in front of or behind the lens.

In particular, I ask myself: how do we deal with mourning when all that remains of the loved one is a photographic reproduction? How are the gaps left between one image and another filled?

Through the medium of photography we delude ourselves into thinking we can preserve memory in an objective way, however it only gives us scattered moments of truth and interpretable narratives. Family photo albums play a unique role for each family: they certify events and ensure the maintenance over time of the facts and people that make up the lineage itself. Sometimes it happens that family photos leave the private sphere to be offered to the public gaze, spread on social media or it even happens that they become the object of artistic reflection.

In this regard, Walter Benjamin's reflection on the first cultural and then exhibition’s function of art comes to my mind, as well as the paradigm shift brought about by photography which, in its reproducibility, enters mass culture, replacing the cultural value of an image with the value of its exhibitability. It is interesting to note how, for Benjamin, it is precisely the human face that retains the last residual aura of that cultural value prior to the reproducibility of images and how this automatically disappears when the human being begins to emerge from photographs. It is no coincidence that the portrait is at the center of the first photographs, in the memory of distant loved ones and the deceased.

Family photography, as a reproducible object, is aimed both at an 'external' audience to convey information, and at a restricted, 'intimate' circle to enrich an emotional heritage linked to the preservation of memory and the custody of family rituals. Looking at our own family photos (but also those of others!) is a recurring moment that is part of the experience of most of us: holidays, trips, birthdays, anniversaries, dinners, weddings, single and group portraits, studied poses and stolen moments. They are always the same photos, as photography historian Roberta Valtorta writes, and yet "in their evidence, in their friendly structure, in the absolute guarantee that they contain true stories, they are sacred objects".

So this sacred aspect of the photography-object brings us back to a deeper dimension: we photograph with the illusion of stealing, perhaps, time from death and in fact photography has added a new time to our life, an added time to the one experienced in the pre-photographic era, a time fixed forever on paper.

Photography makes the action of time visible: this amazing and magical quality of photography is already present in the first article on the new medium published in the Gazette de France on January 6, 1839, in which the author, Hyppolite Gaucheraud, announces "an important discovery that is almost prodigious on the part of our famous diorama painter, Mr. Daguerre". On the one hand, photographic technique is still assimilated to the art of painting, on the other hand, the wonder it arouses thanks to its incredible fidelity to reality is loudly proclaimed and Mr. Daguerre, with his amazing abilities, cannot help but take on the appearance of a modern Orpheus in our eyes:

The act of photographing is immediately perceived as a tool for recording reality that simultaneously retains space and time in its product together with what seems still an insurmountable obstacle: "Nature in motion cannot be reproduced nor could this process do so without extreme difficulty. In one of the views of the avenue I told you about, it happened that everything that was moving did not find a place in the drawing; of the two horses in the carriage in front of the station, one unfortunately moved its head during the brief operation: the animal in the drawing appears headless".

The paradox encountered by the photographer who has the ambition to document the “greatest amount of reality” possible in a single photograph appears when, the more time he wants to record increases, the less the resulting image would be read as a description of reality: this is how Louis Daguerre’s Boulevard du Temple, a daguerreotype depicting the very busy avenue in the third arrondissement, turns into a deserted street (with the exception of the man standing still having his shoes shined) precisely because of the traffic movement that is not captured by the long exposure of about 10 minutes.

Like the artist or the scientist, the photographer must also accept the compromise offered by the limit of his instrument and must choose which small portions of time and reality to grasp and then recompose them later by relying on the extraordinary original trait that characterizes the human being: imagination, or the neurological capacity to fill in the missing parts of a story. Cinema takes up the challenge that photography does not seem to be able to win, that is, to represent reality in time, exploiting, precisely, the ability of the viewer to connect the dots.

As in every medium, to represent reality in such a way that a narrative is conveyed, one must use the process of editing, that is, the succession of temporal and spatial jumps recomposed at the moment of their experience. Collecting, cataloging, classifying photographs inevitably creates an editing.

Reality cannot therefore be described objectively, and the responsibility of interpreting it falls on the viewer, in different ways and with different objectives depending on the era. Therefore, if reality is not objective, it is not unequivocal, even Ray's distorted reality has value, it can be certified, validated: if it is in his mind, it means that it is as real as that in anyone else's mind.

“Mr. Daguerre found a way of fixing the images projected on the bottom of a camera obscura in such a way that these images are no longer the fleeting reflection of objects, but a fixed and lasting imprint that can be transported outside the presence of these objects like a painting or a print. Now imagine the fidelity of the image of nature reproduced by the camera obscura and now add the work of the sun's rays that go to fix this image with every nuance of the day, of the shadows, of the half-tones and you will then have an idea of the beautiful drawings that Mr. Daguerre has exposed to our curiosity. It is not on paper that Mr. Daguerre can work; he needs polished metal plates. It is on copper that we could see the details of the boulevards, of the Pont Marie and its surroundings and of a great number of other places captured with a truth that only nature can give to its works”.

I find the second ordinary story (click on the image to read it.) that opens the chapter relevant to my research for it is the example of the act of editing: we are faced with a photograph that in itself presents nothing remarkable. The absence of one of the two parents in the frame is plausible, as we assume they are the one taking the picture; however, within Giovanna's album, the parent in question is always missing, vanished from the narrative. It quickly becomes clear that this is the result of deliberate editing: the album in itself seems to be drawn from other collections, a selection of a selection with large time gaps and chronologically inconsistent sequences dictated by a conscious choice of what to keep and what to leave out. As Giovanna herself states, each of us photographs and pastes onto the page only what—and only who—is worth remembering.

If a collection already inevitably discriminates among its members regarding which events to preserve, in the physical assembly of an album we are faced with the choice of guiding the family story in one direction or another. The conscious narrative editing of photographic images changes their meaning through a veritable montage: the sequence, grouping, change of context, and even omission define an order, a point of view (that of the individual but also that of the family as a group), which exaggerates certain aspects and gives the sequence a new meaning, conveying a message that might not have been present at the origin of the photograph itself. Is the album, then, a chosen white lie? Do we feel the need for a family epic and the belief that we belong to an enlightened genealogy?

Christian Boltanski's Album de photo de la famille D., 1939-1964, 1971, is the result of the selection of more than one hundred photographs from the family archives of a friend of the author, Michel Durand-Dessert. These are ordinary photographs that the author assembles in chronological order by rearranging memories that do not belong to him. He concludes that this series resembles anyone else's album, an example of social rituals characterized by very similar themes: holidays, first communion, Christmas, baptism, joyful rites of ordinary families.

Boltanski consider that our Western cultural heritage is founded on the collection of objects and that the object itself is the founding sign of civilization. He notes that in non-Western cultures, the ability to construct one or the history they represent is more valuable than the object itself, while, Western Christian culture shows a deep cult of objects: photographs, icons and witnesses of the past, have the constitutive power to tell a person's story, preserving their small memories. Within the big memory that recounts the facts of history, Boltanski focuses a significant portion of his work on saving from oblivion the stories of those who disappeared in concentration camps. Death is the common factor, the battle perhaps lost against nothingness: it lasts the stubborn gesture of the photographer and the artist who, together, fight to leave a trace.

The Ritratti Reali (Real Portraits) project (created in 1972) is just one part of Mario Cresci's twenty-year research journey across southern Italy. It consists of a series of thirty black-and-white triptychs portraying thirty families according to the same compositional rhythm: the first photograph is taken in a long shot, the second in a medium shot, and the third is a close-up of the key detail: the photo of a photo.

The relativity of photographic representation, especially in its role as an impartial testimony of an event, becomes a cornerstone of his research, as for Cresci images are a vehicle and the expression of judgments on reality, transforming themselves into parallel truths. According to Cresci, photography "records and distorts reality; it is therefore in itself ephemeral, even physically erased with the passage of time, becoming a relic, an illegible apparition of actual fragments." The established final point of photography is being the memory of things (understood as a creative act and not as nostalgia), the affirmative human gesture of constructing (or reconstructing) one's own historical and familial identity, despite its inevitable tendency to vanish.

For Cresci, photography is not a description of reality but its transformation into a dynamic movement between circumstance and decontextualization, structure and its dismantling. The families the author presents to us are twice worthy of being included in an album: they are the memory of a moment as a family identity and a mirror of a story within history thanks to the photographs the subjects display. The protagonists become the photographs themselves, in a game of mirrors à la Jan van Eyck.

“When a house is threatened by fire, among the things we immediately try to save are almost always family photos. The old, now disappearing, family albums were, in fact, the updated version of the small altars dedicated to the Lares and Penates, the modest deities who protected the home among the Etruscans and Romans”.

So declares the Modena-born author Franco Vaccari who, invited to speak about Alzheimer's at the 2003 Festival of Philosophy in Modena, installed a video in which, with a handheld camera, he films a series of photographs from his own and other people's collections. He says he drew inspiration for his work from the image of a squirrel "busily filling its burrow with nuts and berries to face the approaching winter." He describes personal and family memories as provisions stored away and used when needed. He identifies old family albums as their richest and most complete source, a source that surpasses even "the forgotten 8mm reels, now impossible to view with the unavailable mechanical projectors" and even "the recent recordings from video cameras, even these, however, threatened by imminent obsolescence."

Photographs are, therefore, our most precious possession because they safeguard the certainty of our memory, which our minds may lose over time or due to pathological causes. Memory is not an organized archive easily consulted on command: its reality is dispersive, is full of gaps and omissions due to oblivion, and some memories are even completely devoid of interest in themselves, except, perhaps, in the eyes of their protagonists. The italian word memoria (memory) derives from its latin etymology recordatio that means the repetition of the action that occurs in the heart (cor, cordis), which for ancient Latin was the seat of memory. Remembering, Re-cordari, then, means to bring back to the heart, a beautiful image that encapsulates the act of bringing to life those "provisions" set aside for the winter.

We have thousands of images packed into our phones and our cloud storage and we almost never look at them. Nevertheless we hold on to them in a possessive way for fear of losing them, at the very same time when we are becoming a humanity devoid of personal, biological, social, historical, and political memory. We capture images at an unprecedented speed and we think less before taking a photograph: the technology that allows us to do so has succeeded in trivializing the meaning of the image itself. An image is just like a written text, susceptible to changes in meaning depending on its context and even, writes Vaccari with poetic intuition, depending on the number and type of empty spaces surrounding it. Memory loss due to cognitive degeneration seems to be precisely the formation of "holes," "voids" within a well-stocked pantry that suddenly seems to leak from the bottom through a hole that can no longer be closed. As time distances the events contained within the frame of the photographic image, individual characteristics become universal, and a personal story takes on the characteristics of a collective, rightfully becoming part of a "tradition." The distance between us and our photographs then also becomes the mental closeness between us and images that do not belong to us: how often does someone else understand what happens to us precisely because they don't walk in our shoes?

The work of these authors shows, in different ways, how it is the context and the juxtaposition of images that convey the narrative's message. None of the photographs have undergone any modification; they have simply been placed in dialogue with other images in a specific sequence or order.

Erik Kessels meditates on the power of images derived from their disproportionate quantity, from their becoming infinite copies, copies of copies, the same selfie taken by thousands of people in the same place to prove that I was there too.

In his anthology, The Many Lives of Erik Kessels, he focuses on imperfection within a world that aspires to perfection. He is fascinated by the photographs he acquires at flea markets and online, observing how they are often marked by flaws, repetitions and clichés. The artist observes how in every family album of the pre-digital era, anywhere in the world, it emerges that amateur photographers were not obsessed with the pursuit of the perfect shot; their intent was simply to capture a memory, to immortalize significant moments in their lives. Kessels senses how today, on the contrary, we are overwhelmed by excessive consumption: we devour images as quickly and superficially as a fast-food meal, ingesting them in quantity without truly assimilating them.

Here, the author reappropriates the discarded images, the ugly ones, as in Album Beauty, a project published in 2012 that becomes a tribute to the family album and its swan song: through the thoughtful appropriation of strangers’ photographs, he constructs an unexpected story and forces the viewer to "fill in the blanks by focusing on the details," preventing a passive gaze and, indeed, pushes to search for answers. The fact that, for example, quite often are the fathers the obvious authors of the photographs (again, we are forced to deduce as they never appear), leads the author, and us with him, to ask ourselves what and how the unknown photographer looked at the person he was photographing, deducing in a sharp way an invisible personal story.

On the same wavelength I’ve found the work of Joachim Schmid and in particular the book series Other people’s photographs, 2008-2011. Assembled between 2008 and 2011, this series of 96 books explores the themes and visual patterns present in the everyday lives of amateur photographers. Images found on photo-sharing sites like Flickr have been grouped and organized to create a library of contemporary vernacular photography in the digital era.

Schmid's approach is encyclopedic and the series is virtually infinite, yet arbitrarily limited by the author: even if they aren't strictly a family album, the personal photographs of individuals who have chosen to share them online always depict the same things, just like family photos. The author seems to highlight the human need to repeat the act of photographing, not only to document an extraordinary or unusual event, but also simply to declare our existence — or rather, not to bear witness to what we see, but to affirm having seen it.

This is perhaps the extreme point of an argument that could already be made for family album collections, where we are careful about what we want to remember. In this case, the original source —the original photographs released online— is less redacted. Having the possibility to take a exponentially greater number of photographs and being able to archive them digitally, it means we no longer have to choose, we can virtually document any moment, which is why Schmid has to stop at 96 volumes when he has enough material to continue endlessly.

Through pop, amateur photography, Schmid argues that the reality represented is an illusion, and that decontextualizing it through a simple act of redaction is enough for our perception to fool us: the single story that would otherwise hide interesting and unique details, placed within a repetitive sequence, flattens until it merges with all the others in a bigger, social picture.

This research is about memory and travel.

Its core has produced both my master thesis and the project

Where have you been today? (2025).

Being these two parallel paths strongly intertwined, bear with me along

this journey that will take us from one to the other and back again.

What about photography, then?

Behind the idea of a family album lies the making of one or several choices, some of which are inevitable. Not only have we chosen what to photograph and which portions of space and time to collect, but we have also created a representation of a portion of who we are, of what we want to show to the others.

The deeper we step into the pages of our album, the more we go against the definition and declaration that photography is a representation of reality: taken in one way, organized in another, edited in a third, the family album is the protagonist of a parallel reality, a different story.

This applies not only to the grand history written in textbooks but also to a small memory like that of a family. Like a magician's trick, photography offers us partial information, giving us the illusion of approaching the experience of reality in its entirety, leaving our brain to deceive itself.

Why the album, then? We photograph the living, anticipating to remember them when they are no longer with us, We want, maybe, be able to make an impossible transition and, perhaps, reach them, even for a brief moment. Contemporary photography has the power to reveal a conditional past: it could have happened.

As Marshall McLuhan already intuited in 1964, photography even when not directly manipulated - is by its very nature non-objective and offers a partial and questionable vision. In a family album, the strongest message is the one that emerges from a more subtle reading, the one conveyed by what is unseen, what was left out of the frame, what was left out of light.

A family album is partly testimony, partly artifice, and the two are so closely intertwined that they often confuse us. What appears with shadows, shapes, and contours is surrounded by voids that the brain fills as best it can, reaching where the eye can no longer reach, where the light doesn't fall. If photography is no longer the instrument of accuracy, precision, and truth, then it is the subjective, personal experience that matters, and in this light, my grandfather Ray’s dreamlike, distorted, and unreal memories are as real as anyone else’s, and therefore worthy of witnessing.

This final ordinary story (click on the images to read it.) is an example of multi-layered manipulation, a fiction both in front of and behind the lens: at the moment of the shot, Vittoria wears a wig that hides the truth of her illness, but the subsequent manipulation, with the toning of the colors to black and white, ensures that the fiction is not revealed. It is interesting to note how, during this story, not only a (double) manipulation was carried out but also a subsequent redaction of the images: the grandmother, the one who received the color version of the photograph, the "truer" one, eliminated the dramatic significance of the picture changing its context, introducing it into a montage of happy moments.

Photographic manipulation has existed since its invention, from the roughest af all, a rip of the paper tearing and eliminate an unwelcome subject, to the more sophisticated manipulation of photomontage. But what if, after looking at a photo album chronicling a woman's life, we discovered it to be a complete and utter fiction? The Fae Richards Photo Archive, a project that artist Zoe Leonard conceived in collaboration with filmmaker Cheryl Dunye as a visual support to the film The Watermelon Woman (1996), directed by the latter, is a personal photo album comprising eighty-two images documenting the life and story of a fictional person, Fae Richards, a gay, African-American actress and blues singer, from childhood to adolescence, from Hollywood fame to the Civil Rights era when her career was hindered by racist sentiments, and finally into her old age as a forgotten star.

Each image is the result of a carefully constructed mise-en-scène, with attention to detail for the sake of overall realism. Even the captions are written on an old typewriter, and many of the photos have been manipulated to simulate the patina of aging. The artifice is revealed only through the acknowledgments at the end of the sequence, when the author publishes the list of all the women hired to play Fae at different stages of their lives (even the artist’s mother).

Upon closer inspection, however, this fictional archive becomes the spokesperson for the lives and stories of women who really existed but whose traces have been lost, women marginalized because they were subjected to racism, classism, homophobia and misogyny. Fae's life is truer than reality; artifice becomes authenticity: we had to invent her, the author seems to be saying, because the lives of other women had never been documented.

While queerness and invisible archives are two elements that often go hand in hand (see photographer Lisetta Carmi's major work, I travestiti, 1972), Zoe Leonard's work, however, has a broader scope: it engages the viewers to such an extent that they are unable to remain neutral, driven to take a stand. Photography, so dangerous in its plausibility, allows us to explore a magical and suspended portion of space and time, that of the "possible," and, in doing so, provides the imagination with a variety of viable paths.

Did they ever call you Nana?

I’m not Nana, I’m Evelyn.

Ok, is it okay if I call you Nana?

Banana?

No. Just Nana.

Why?

Because. That’s what I’ve always called you. I’ve always called you Nana.

Alright. Nana would be alright.

You Can Call Me Nana by American photographer Will Harris is a work that feels deeply familiar to me. It begins with his personal story but becomes straight away universal thanks to the unmediated language of photography.

Mrs. Evelyn Beckett, the author's grandmother, suffered from severe dementia in the last years of her life, and her grandson, in response to the inexorable erosion of her memories, takes it upon himself to become responsible for them. Grief and love take on a narrative form: conversations are transcribed, her home, her objects and herself are photographed in a constant but unconscious collaboration between grandmother and grandson that seems to occur on a non-verbal level.

It is a book that recalls the essence of a family album: we try to understand the past, because what happened before us made us who we are. Photography changes the familial relationship between the viewer and the viewed: the author seems to want to simultaneously stop time and confuse it, as if trying to deceive even the advancing disease. The images are often grainy, blurry, damaged and blurred, so much so that the protagonist seems to want to escape the objectivity of reality. Where he can no longer physically converse with his Nana, a new dialogue opens up with the viewers in a journey of meticulous disorientation thanks to grandma Evelyn, who escapes from the page and comes back to it, is lost and then, perpetually, found.

Moira Ricci's work - 20.12.53-10.08.04, 2023 - also addresses loss: on the very day of her mother Loriana's sudden death, Moira Ricci, in an attempt to deal with grief using the only language she knows, places herself inside a photograph with her. Thus begins a ten-year journey, a way of rewriting history. In her photographs, the artist-daughter never smiles but looks at her mother with a longing gaze, attempting to "warn her of impending doom." In each image, the two temporal planes of past and future coexist in an impossible present. Over the course of ten years, she produces images that become increasingly elaborate, increasingly precise, images that take on a broader meaning in an artistic journey that is no longer simply the processing of her own grief but a declaration of her being a photographer. Digital and analog are one: the manipulation is digital (with Photoshop in its beginning, still lacking today's capabilities), but it is also real, as Ricci must interpret herself by manipulating true reality by photographing herself with disguises and facial expressions: her presence is not "real," but we allow ourselves to be fooled. What Freud calls the "intermediate realm" is born, that of art, which allows us to express our unconscious fantasies without danger or transgression. Thanks to this irreplaceable alchemy, art allows the life drive to prevail over the death drive, creation over destruction. Losing is also always winning, gaining freedom, vitality, a new identity. In initiation rites, death symbolizes a future rebirth.

Installation view of all 254 postcards in occasion of my thesis presentation in the courtyard of the Brera Academy of Fine Arts. They are exhibited on a revolving display: all the visitors could browse and choose a card to keep.

Visualization of the pictures taken to synthesise the final model, here shown alined in the virtual space

Bibliography

AA.VV., A history of photography, from 1839 to the present, Taschen, Köln 2022

AA.VV., I AM A CAMERA, the Saatchi Gallery Booth-Clibborn Editions, London 2001

AA.VV, Catalogo Nazionale Bolaffi della Fotografia, Giulio Bolaffi Editore, Torino 1977

Araki N., Sentimental Journey, Self Published, 1971

Araki N., Sentimental Journey, Winter Journey, Shinchosha, Tokyo 1991

Araki N., Sentimental Sky, Rat Hole Gallery, Tokyo 2012

Araki N., Sentimental Journey 1971.2017, HeHe, Tokyo 2017

Auster P., L’invenzione della solitudine, Einaudi, Torino 2010

Barchiesi L., Donne è Bello, Postcart Edizioni srl, Roma 2020

Batchen G., Hiding in Plain Sight, in Negative/Positive, A history of photography, Routledge, UK 2020

Boltanski C., Les modèles, cinq relations entre texte & image, intervista con Irmeline Lebeer, 1979

Boltanski C., a cura di Semin Didier, Charles Boltanski, Phaidon, Londra 1997

Bryan -Wilson J. e Dunye C., Imaginary Archives: A Dialogue, Art Journal 72, n°2, Giugno 2013

Carmi, L., I travestiti, Essedì Editrice, Roma 1972

Chomsky N., Le strutture della sintassi, Laterza, Bari 1970

Corà B., Maggia F., Araki. Viaggio sentimentale, Gli Ori/Centro per l’Arte Contemporanea, Luigi Pecci, Prato 2000

Cortellessa A., L’ombra della vita, in 20.12.53-10.08.04, Corraini Editore, Milano 2023

Cresci M., L'archivio della memoria. Fotografia nell’area meridionale 1967/1980, Regione Piemonte, Torino 1980

Cresci M., Misurazioni. Fotografia e Territorio, Yard Press Edizioni, Roma 2020

Cresci M., Mario Cresci. UN esorcismo del tempo, Contrasto Edizioni, Roma 2023

Didi-Huberman G., Immagini malgrado tutto, Raffaello Cortina Editore, Milano 2005

Ferrari D. e Pinotti A., a cura di, La Cornice, Storia, teoria e testi, Johan & Levi Editore, Milano 2018

Ferrari S., Tartarini C., AutoFocus, L’autoritratto fotografico tra arte e psicologia, CLUEB edizioni, Bologna 2010

Flem L., Come ho svuotato la casa dei miei genitori, Archinto, Milano 2004

Flem L., Nel regno della lira digitale, in 20.12.53-10.08.04, Corraini Editore, Milano 2023

Fregni Nagler L., The Hidden Mother, MACK, London 2013

Fontcuberta J., La furia delle immagini, note sulla postfotografia, Einaudi, Torino 2018

Foster H., An Archival Impulse, The MIT Press, Ottobre, 2004

Gaucheraud H., Gazette de France, edizione del 6 gennaio 1839, Parigi, Francia

Garb T., Semin D., Kuspit D., Christian Boltanski, Phaidon Press, London 1997

Genard P. e Barret A., Lumière, les premières photographies en couleurs, Trésors de la photographie, André Barret éditeur 125, Paris 1974

Gerard J., The Herball or Generall Historie of Plantes, Imprinted by John Norton, London 1597

Harris W., You can call me Nana, Overlapse Publishing, London 2022

Jobey L., Ray’s a Laugh: A Reader, Mack, London 2024

Kessels E., Album Beauty, RVB Books, Paris 2012

Kessels E., The many lives of Erik Kessels, Aperture, NY 2017

Kessels E., In Almost Every Picture (vol. 1-19), KesselsKramer (and Artimo per i vol. 1-3), Amsterdam 2002-2024

Larson K., New York Magazine, 1989

Lavedrine B. e Gandolfo J., L'autochrome Lumière : secrets d'atelier et défis industriels, CTHS EDITION, Paris 2009

Leonardi N., Fotografia e Materialità in Italia:Franco Vaccari, Mario Cresci, Guido Guidi, Luigi Ghirri, Postmedia Books Editore, Milano 2013

McLuhan M., Gli strumenti del comunicare, Il Saggiatore, Milano 2016

Ricci M., 20.12.53-10.8.04, Corraini Editore, 2023

Scarry E., The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World, Oxford University Press, 1985

Stallabrass J., High Art Lite: British Art in the 1990s, Verso Publishers, UK 2001

Dugan J. T. , Strange Fire Collective, 2021

Vaccari F., Fotografia e inconscio tecnologico, a cura di Roberta Valtorta, Einaudi Editore, Torino 2011

Valtorta R., Il pensiero dei fotografi, un percorso nella storia della fotografia dalle origini a oggi, Bruno Mondadori Editore, Milano 2008

Valtorta R. (a cura di), Joachim Schmid e le fotografie degli altri, Johan & Levi editore, Monza 2012

Valtorta R., Il tempo, la verità, in 20.12.53-10.08.04, Corraini Editore Milano 2023

Wilson B. J. e C. Dunye, Imaginary Archives: A Dialogue (2013)

Winant C., My Birth, Self Publish Be Happy, London 2018

Zanot F., Houdini’s Burqa. A conversation with Linda Fregni Nagler in L. Fregni Nagler, The Hidden Mother, MACK, London 2013.

Zoja L., Vedere il vero e il falso, Einaudi, Torino 2018