Historically Informed Soundscape: Mediating Past and Present

D. Linda Pearse, Ann Waltner, and C. Nicholas Godsoe

Imagine for a moment that the only way we engage with early music manuscripts is through inspection of the musical text, without any attempt to perform it. Imagine again that musicians who perform early music made no attempt to engage with the historical context and performance practice of the past. Performative artistic research attempts to engage with these practices and contexts. Can we engage with auditory culture from different time periods by adapting methods from early music performance practice to create soundscapes? Will the process and product of creating a historically informed soundscape provoke new conversations and generate a new type of knowledge to engage both scholars of auditory culture and audiences?

Specialist performers of early music employ research and performative experimentation to create historically informed performances that speak to our present tastes and aesthetics as well as to the historical materials that provide context for the music. Their work engages scholars and artists through the medium of performed sound and offers the products of that work for scholarly consideration. Might the collaboration between scholars and performers in creating historically informed performance help us conceptualize ways of making historically informed soundscapes? What are we missing by not creating historically informed soundscapes in this way? Granted, non-musical sound and music exist in very different contexts and leave different kinds of evidence, but they are both part of an auditory culture which we are interested in investigating. We aim to complement scholarly narratives that seek to better understand the sounds of the past beyond musical domains by borrowing methods and models from early music performance and adapting them to create historically informed soundscapes.

A soundscape is the collection of sounds in any given environment – both natural and man-made – that is often understood to be non-musical. Art and scholarship that engage with soundscape were initially interested in preserving sound through recording, raising awareness about noise pollution, and understanding how particular sounds resonate with certain communities. More recent scholarship that engages with auditory culture seeks to explore and better understand the role of sound in historical contexts. This work has been done by scholars in a number of disciplines, notably history and art history (Atkinson 2016; Peri 2017; Rath 2014; Smith 2004). Further, some creative projects use historical information to sound otherwise silent texts and images from the past in order to create broader understandings of a particular time and place in history.[1] While our work is certainly informed by such pursuits, our approach differs in that we are primarily engaged in the production of an artistic work. The resources we use and the goals we strive to achieve embrace the present as well. We consult historical information about our subject and use that knowledge but are not restricted by it. We are creating sound to respond to the past, not sound of the past; we are focused on a broader understanding of sonic events and how they are connected with the present. Our soundscape includes recorded natural and urban soundscapes, live performed soundscapes, texts, and music. Bringing all of this together, we are creating an artistic work that engages with the meaning of sound over time.

Historically Informed Performance and Authenticity

The inspiration for this article lies in an in-progress project that seeks to create historically informed soundscapes to evoke the lives of two historical women – Kateri Tekakwitha (ca. 1656–1680) and Fatima Hatun (neé Beatrice Michiel, ca. 1553–1613). Kateri Tekakwitha was a Mohawk who lived in what became the Kahnawà:ke territory (near Montréal) and converted to Christianity without relinquishing her indigenous identity; she was canonized as a saint in 2012. Fatima Hatun (née Beatrice Michiel) was a Venetian Catholic who moved to Istanbul and converted to Islam; she and her family played an important role in Ottoman Turkish society. These two women defy conventional categorizations of race, geography, gender, religious identity, and country. Their stories are inspiring in the way they navigate complex cultural and religious identities.

The soundscapes will be embedded in a larger interdisciplinary artistic creation that weaves images, soundscapes, music, and text to create a performance that provokes thought about cultural and religious contact during the early modern period in both New France and the Mediterranean. This is the third such performance piece that we have designed.[2] The larger work includes the performance of Mohawk dance, singing, and drumming by musicians from Kahnawà:ke; music brought by Jesuit missionaries; seventeenth-century Venetian music performed by the early music ensemble ¡Sacabuche!; Ottoman music performed by musicians from Istanbul; and historical texts, images, and soundscapes. For this project, our soundscape includes recorded sounds, live performed sounds, texts, and music. The early music and textual examples that we discuss here will not necessarily be included in the final project; they serve to illustrate our approach and contextualize our work and thought processes.

We borrow a methodology from the historically informed performance practice used in the study and performance of early music and apply it here to create historically informed soundscape composition. The term “historically informed,” when applied to early music research and performance, assumes that scholar-performers of early music acknowledge the limitations of our knowing. We acknowledge that we cannot go back in time, we cannot know exactly how music sounded, and we cannot authentically create a performance identical to one performed hundreds of years ago.

The term “authenticity” was used in media, conversation, and scholarship surrounding the performance of early music throughout the twentieth century. Although many performers understood that the goal of creating “authentic” performance was unattainable, journalistic and promotional materials employed the word frequently (Fabian 2001). The use of the term “authenticity” increased during the 1950s to 1980s, which signaled a growing awareness of the early music movement within mainstream classical music circles (Fabian). Early music performers turned away from the continued application of nineteenth-century styles that were standard for the performance of most classical music. They instead considered historical evidence surrounding the music they sought to perform. They performed on historical instruments (or copies of historical instruments) and consulted and engaged with the extant musical score instead of with modern editions of the music. Throughout the twentieth century, luminary thinkers on early music, and performers of it, such as Richard Taruskin (1982), Nicolaus Harnoncourt (1980), Christopher Hogwood (1984), and others, voiced concern over the use of the term “authenticity,” recognizing that it is impossible to recreate the way early music was performed in its own day.[3] Scholars and performers began to adopt the concept of “historically informed” performance to describe the attempt to come closer to the past while acknowledging that early music performed today is informed by the present as much as – if not more than – the past. This concept has strong resonances with ideas about the nature of the past and its relationship with the present articulated by Walter Benjamin and Paul Ricoeur.[4]

At first glance, this acknowledgement may seem to discourage inquiry into early music performance practice – after all, why should we endeavor to come closer to the past if we know that we shall never succeed – but it also points to a methodology and process characterized by research and performative experimentation. The methodology points to an imaginative process that is tied intimately to our current understanding of the past. These understandings change over time, and our ideas about how historically informed music sounds changes with them (Upton 2012: 2). In short, our idea of the past is malleable and ever-changing. Dorottya Fabian notes that prominent early musicians have expressed that “their focus of interest was to recreate works of art for the present, and in as musically effective manner as possible” (Fabian 2001: 167). Thus, the process of creating a historically informed performance of early music becomes a dance or a dialogue between past and present – a negotiation between, on the one hand, historical evidence and on the other, a present-day interpretation of musical aesthetics and of the past. We find the processes we use in constructing historically informed performance to be useful as we think about creating historically informed soundscapes.

Creating Historically Informed Soundscapes

Creating a soundscape for a historical topic presents a distinct set of challenges. There are no recorded sound files from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Visual evidence and historic texts provide some information about sound, but sound is normally not the focus of these documents.[5] Furthermore, visual and textual sources are mired in a problematic of perspective, given that authors cannot help but interpret the subject through their own cultural lens.[6] We often encounter silence – a lack of information – when investigating past sounds. We need to find a way to confront silence as we create historically informed soundscapes.

Aural historians are aware of the limitations of this particular mode of historical investigation. Richard Rath, for instance, is well aware that sound is ephemeral and that any scholarly inquiry into bygone soundscape will be ambiguous and imprecise: “The construction of the soundscape is not meant to be ironclad. It is intended as a rubric […] The rubric is useful as a starting point for efforts to unearth historically constructed assumptions about how we hear. It gives us a frame for comparisons with other times and places and thus helps us denaturalize and historicize our sense of hearing” (2008: 428). Applying the method of the early music scholar-performer to the creation of historically informed soundscape opens doors to understanding sounds of the past, acknowledging that there is no standard, coherent, or reliable way of understanding perceptions of sound from printed evidence, the central means through which aural historians do their work (Smith 2004: x). Our method places soundscape creation within an artistic medium. In this context and as with early music performance, the artist does not aspire to recreate an “authentic” sound of the past but one that engages with our present understanding of past sound as well as our understanding of that sound over time.

Soundscape Literature

The practice of considering sound and listening in a historical context is well established in scholarly circles. Initial interest in historical sound is seen in foundational work in soundscape studies and has since manifested itself in a sub-discipline of history, sometimes described as aural history, which concentrates on understanding the role of sound in historical contexts. Most relevant for our project is understanding the development of how the sounds of the past have been imagined and used by scholars and how these understandings and applications have changed over time. Although an interest in sound’s role in history is ever-increasing, scholars and artists are only beginning to engage with historical soundscape composition in artistic contexts. We do not have enough models for creating a soundscape which evokes sounds of the past. There is need for soundscape artists and scholars to develop these models, to experiment with historically informed soundscape, and to explore what is a new type of knowledge – a knowledge that provides a new way of imagining past sound.

The earliest writings about soundscape in history came from R. Murray Schafer (1977) and Barry Truax (1984), who established soundscape studies as both artistic practice and academic pursuit. This foundational work on soundscape was largely concerned with articulating new concepts such as acoustic environment and communication, the cataloguing and preservation of soundscape, and raising awareness of noise pollution. Schafer acknowledged that in studying soundscape, “we are disadvantaged from a historical perspective” (1977: 8). Sound leaves no concrete record of its presence or occurrence in the past, leaving room for only ambiguous, minimally informed historical understandings.[7] In spite of this, both Schafer and Truax agreed that the best way to productively engage with and understand historical soundscape is through what Schafer described as “earwitness accounts,” written accounts from people who described the sounds of their own time and place (1976: 8). Some of his key concepts remain central to the practice of aural history (Smith 2004: xi).[8]

Writing at the same time, David Lowenthal turns his attention to the notion of historical soundscapes, or as he describes it, the “audible past.” He describes his work as “the first exploration into past sounds and our feelings about them” (Lowenthal 1976:15).[9] Lowenthal begins his exploration by presenting basic yet essential questions in considering how the past may have sounded and how we might engage with it through a contemporaneous lens:

What becomes of music, speech, and other sounds, natural and man-made, when they cease reverberating? How far do previous sounds differ from those of today? How much do we remember about what we hear? What meanings and emotions attach to sounds from the past? Why do familiar sounds often trigger nostalgic yearning? What sound do we regard as antiquated, and why? (Lowenthal 1976: 15)

Lowenthal wonders if this kind of pursuit is feasible and concludes: “[g]iven our present level of technology, past sounds, strictly speaking, appear to be irrecoverable. Sounds persist only in memory, often evoked by associations, and in their influence on imagination” (1976: 17). Early music scholar-performers drew similar conclusions with respect to the realistic expectations of recreating music of the past.

This ephemerality of sound does not stop historians from speculating on the role and significance of sound in historical contexts; sound’s ephemerality is an area of intrigue that self-described aural historians relish. Mark Smith explains in the introduction to his reader Hearing History – a benchmark publication that firmly establishes aural history as a historiographical practice – that at around the turn of the twenty-first century, “historians are listening to the past with an intensity, frequency, keenness, and acuity unprecedented in scope and magnitude” (Smith 2004: ix). Smith’s reader, and other key publications by Richard Rath, seek to demonstrate that listening to history has much to offer; understanding how history sounded can allow historians to analyze and interpret history in novel and productive ways. Aural historians aim to broaden discussions of sound in history beyond music, understand the ramifications of changing soundscapes, and speculate about what sounds may have been present in certain historical settings in efforts to historicize our sense of hearing. They strive to become more critical and aware of how people described the sounds of their surroundings and communities in writing. For these reasons Rath displaces claims that historians cannot securely explore the roles of sound and oral tradition in history because of their unstable, intangible, and ephemeral nature. Rath maintains that these assumptions are both misleading and mistaken; it is not the job of the historian to create the past. Rather, it is the job of the historian to interpret that past, using all means available (Rath 2008: 417). Rath believes that the best way to tap into and understand history’s soundscape is through what he describes as soundways: “the paths, trajectories, transformations, mediations, practices and techniques – in short, the ways – that people employ to interpret and express their attitudes and beliefs about sound […] Soundways can be readily found in many types of documents, textual and otherwise” (Rath 2008: 419). But Rath’s idea that information about historical soundscape can be gleaned from non-sonic historical sources is not entirely new. Schafer outlined his concept of the “earwitness account” – descriptions of sound in mythological, anthropological, or historical records – decades before Rath introduced his notion of soundways into scholarly discourse (Smith 2004: 6). But the key difference between these two thinkers is in their divergence on the limits and the potential of such sonic descriptions. While Schafer suggests that, in understanding historical soundscape, “we are disadvantaged from a historical perspective,” (Smith 2004: 6) Rath is more optimistic. He understands historical references to sound as “no more nor less ephemeral than other human patterns in the past” (Rath 2008: 419). Rath and Schafer also aim to explore different questions with the same historical material. While Schafer is interested in understanding how soundscapes have changed over time, Rath is more interested in understanding the role of sound in isolated historical contexts. More recently, art historians such as Niall Atkinson (2016) and Deborah Howard (2009) have used evidence from the built environment to reconstruct sounds of the past, and historians like Alexis Peti (2017) have used diaries to reconstruct somatic experiences of the past, including the experience of sound.

This project is selectively inspired by all of these scholars. Like Rath, the authors of the present article are not afraid of the ephemerality of sound. However, we hope to move historical soundscape research beyond the realm of academic discourse and into an artistic context; we are engaging with ways of hearing the past that scholarship alone cannot address. We have immersed ourselves in documentary evidence, but we are not constrained by that evidence in the same way a scholar would be. And it is not only the past that concerns us: we are interested in fostering a dialog between present and past soundscapes and engaging with the meaning of sound over time. In this aspect of our work, we find Schafer particularly useful.[10] Looking to models of historically informed early music performance for the creation of historically informed soundscape may serve as a starting point.

Methods for Creating Historically Informed Soundscape

Historically informed performance is produced through scholarship and performative experimentation; we propose to create historically informed soundscapes using these methods as well as those employed by soundscape researchers. To illustrate the application of these methods to the creation of soundscape, we take examples that are central to our current work. We discuss the soundscape that we are currently devising for the portion of our project, which looks at the life and legacy of Kateri Tekakwitha. Tekakwitha was a Christian convert who retained her Mokawk identity; three Jesuits who were her contemporaries wrote extensively about her. As a result, we have an incomparable trove of sources on her life.[11]

Four steps characterize our creation of the soundscape: gathering evidence, generating sound, experimenting with sound, and creating the soundscape. Gathering evidence includes a variety of activities, both consulting historical accounts and doing fieldwork in Kahnawà:ke. The most important historical accounts of the life of Tekakwitha are those written by the Jesuits who knew her, but other accounts of early New France have been useful in imagining sounds (Thwaites 1903). To prepare for fieldwork in Kahnawà:ke, we read works by anthropologist Audra Simpson (2014) and soundscape researchers Helmi Järviluoma and Noora Vikman (2013). Once in Kahnawà:ke, we engaged in conversations with residents, we observed a pow-wow and met with performers. Generating sound includes making recordings of present-day sounds that resonate with the present and past as well as workshopping with the musicians of ¡Sacabuche! to create live soundscapes. We recorded sounds of the natural environment in Kahnawà:ke and of the people and pow-wow.[12] Experimenting with sound is a process like that of the early music musician, which includes listening and evaluating the recorded sounds and rehearsing the live performed sounds. For this project, experimenting with sound includes layering recorded and live sounds to create possible constellations of the media and trying out and revising these constellations with spoken text.[13] It is with these additional steps and the use of recorded sounds and modern equipment that the analogy with early music breaks down. As a final step, we will create the recorded soundscape and determine the live soundscape constellations that we will sound during the performance. Three concepts inform this creative process: performance as research, texts informing sound, and engaging with place and the present to inform the past.

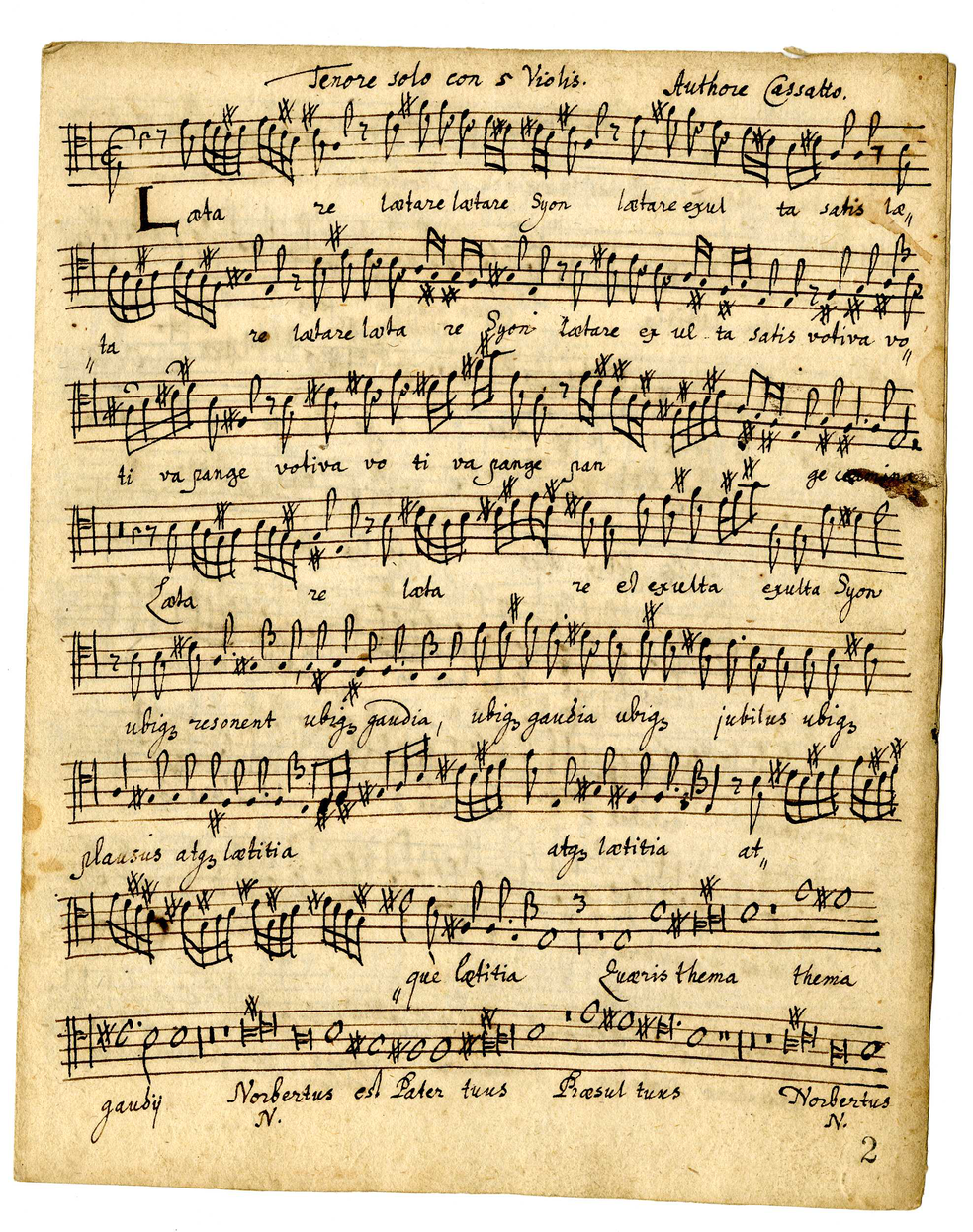

The complete manuscript of Laetare Syon features one voice and five instruments (variously marked in other parts for strings and trombones) plus basso continuo, but it does not include a full score. At the beginning (upper left) of the part, a tenor clef indicates the location of middle C on the fourth line from the bottom. A duple mensuration sign (cut-C) appears next to the clef and a tripla (3) appears in the middle of the seventh line of music from the top, indicating the tactus (or pattern of beats) that the performer will use. There are no bar lines. Musica ficta (similar in appearance to sharps or flats in modern notation) indicate a change in pitch by half step and refer to the note next to which they appear, or occasionally to multiple notes.

Bringing a musical part to sound engages musicians in a process of imagination, deliberation, and experimentation, employing textual and visual evidence, and relying on musical intuition, training, and the understanding garnered through the acts of practice, rehearsal, and performance. Through the process of creating the critical edition (Pearse 2014) we made decisions about how to represent the work in modern score. We decided how best to impose a meter on the work and decided on suggested relationships between the many sections of duple and triple meter. In part, these decisions were informed through rehearsal and performance of the work, in part through a consultation of primary and secondary source materials. Generating sound and what we learn through that process can reveal what the music offers that is not readily apparent through score study alone.[14] Adorno notes this distinction:

The musical score is never identical with the work; devotion to the text means the constant effort to grasp that which it hides [...] an interpretation which does not bother about the music’s meaning on the assumption that it will reveal itself of its own accord will inevitably be false since it fails to see that the meaning is always constituting itself anew.[15] (Adorno 1983: 144)

The musician experiments with many parameters of sound: phrase shape, articulation, dynamic, tempo, use of expressive devices, and technical execution. There is a materiality to the production of sound that has a different chain of processes than that of non-performative scholarship. Musicians are not talking or writing about sound, they are making sound with their hands, fingers, voices, lips, breath, or body. A sackbut player can visit a music instrument museum, observe and possibly play on a sackbut from the seventeenth century. The player can combine the modern skills of sound production and technique and engage with the physical presence of the historical instrument, gaining insight on pitch, tessitura (range of the instrument), response, articulation, and more. The early musician combines this practical application with a consideration of treatises and early manuscripts, performance acoustics, information derived from court records and travelers’ accounts, visual depictions of instruments, contemporary writings on, instruction, scholarship, and recordings of early music. The musician makes connections between materials, facilitated by the act of playing the instrument and the music associated with it.

To bring Corda Deo dabimus to performance, we engaged in a process similar to what we described above for the Casati text. We transcribed the music into a modern score edition, facilitating rehearsal with the ensemble. We transcribed the text and had it translated so that the musicians could easily understand the meaning of the Latin and how it might relate to the written music. We combined score study with our understanding of treatises on performance practice and our skills as musicians to bring the music to life. For example, the opening phrase “Corda Deo dabimus” (we will give our hearts to God) is sung using an Italianate pronunciation; Ercole Porta, the composer, was Italian and composed this work in Italy. We give the third syllable of the word “da-bi-mus” the lightest stress, as we would if it were spoken. We notice that the strongest suspensions (notes sounding over the bass note that create a sense of tension and longing for resolution) occur on the syllable “da” of “da-bi-mus.” The note length is longer for that syllable than the notes preceding and following it, and the voice part ascends to the highest note. The overall musical setting of the text supports a shaping of the phrase that places the greatest emphasis on the syllable “da-” of da-bi-mus and a lightening of stress on the final syllable “-mus,” mirroring the pronunciation of the Latin. The shape of the phrase produced by the singers and trombones leads to this moment and then relaxes and lightens into the third syllable “-mus.” We perform this kind of analysis on the entire score and text and use it to inform our performance. Our assumptions about language and stress come from our knowledge of supporting evidence in treatises and information informing the composer and score.

The act of producing sound and performing the music informs the performer’s understanding of textual – non-sounded – evidence just as the textual evidence informs performance. For example, an examination of the treatise on diminution Il vero modo di diminuir (1584) by Girolamo Dalla Casa informs our understanding of articulation for players of early wind instruments. Dalla Casa suggests several options for multiple tonguing appropriate for notes of eighth note value or faster (forming different syllables in the mouth to produce a faster and more varied articulation) and two options for single tonguing appropriate to the performance of diminutions in eighth notes.[16]

Internationally acclaimed cornetto player Bruce Dickey notes that the musician must experiment with the instrument to find the techniques needed to realize concepts sketched in the treatise.[17] The treatise provides little information on how musicians played those notes as regards dynamic, stress, and timing. Dickey considers how to approach the performance – articulation, stress, and style – of slower notes, employing information from the treatise, information from other historical sources, and his experimentation with the instrument. In my correspondence with Dickey, he makes the following observations:

On wind instruments the multiple tonguing syllables (lingue), which are employed on divisions from the value of eighth notes and faster, create – or can be allowed to create – a kind of automatic inequality for these rapid notes where a more deliberate use of breath and timing would be impractical. On notes from the quarter note and slower, such paired tonguings are not necessary, but a sensitive player would clearly have imitated the irregular stresses of the text, either a real or an imaginary one. This is nowhere clearly described but follows, I think, from an understanding of the idea of imitating the human voice. Ganassi says, "know your goal [in playing a wind instrument]: imitar il parlar (to imitate speech)."[18]

The problem area, and it always strikes me that the players (and singers) around 1600 struggled with this just as much as we modern players do, is the eighth notes. All discussions and illustrations of this sort of inequality focus on the level of eighth notes: Caccini, Brunelli, Bovicelli, Zenobi, etc. And interestingly, this is the “pivot” point for tonguing syllables. Eighth notes can be played either with the multiple tonguing syllables or with the single tonguing syllables “te te te te” or “de de de de.” I firmly believe that this does not mean eighth notes were played equally. That would go against the entire aesthetic surrounding the imitation of speech. On the contrary, having the possibility of tonguing these notes as pairs or as single strokes gives the player an infinite variety of kinds and degrees of inequality. [19]

Performance as Research

Two salient aspects of an early music performer's work are 1) that the act of performing informs research, just as research informs performance and 2) that the act of performance requires a commitment to a version of the music that is concretized through performance.

Music manuscripts and early printed musical parts supply invaluable information for the early music performer. The Baroque manuscript provides a basic structure for the work, including the notes, part names, lyrics, meter or mensuration, and a bass line for the basso continuo performer. However, a musical part from the seventeenth century is often devoid of indications of phrasing, dynamics, articulations, and bar lines. Here, the musical part serves as a guide, but not more.

The recording features La Novellina by Gioseffo Guami, a work demonstrating the florid and virtuosic style of solo music around 1600 and featuring Bruce Dickey playing the cornetto with basso continuo accompaniment. Apart from the overwhelming beauty and grace of Dickey’s playing, of relevance here are the ways in which he shapes and articulates the eighth and sixteenth notes. At seven seconds into the recording, we hear the first eighth-note passage. A slight inequality of articulation and stress is noticeable as Dickey performs the ascending line, creating a forward direction to the line and piquing the interest of the ear. At fifteen seconds we hear the application of the multiple tonguings described in the Dalla Casa treatise in a long and florid sixteenth-note passage. Dickey’s intent to imitate speech is made clear by his phrase shapes, overt lyricism, articulation, and way of carrying his sound – certainly a valid and beautiful interpretation of the treatises transferred to sound.

As regards playing the faster notes, Dalla Casa’s tonguing syllables produce unequal note lengths and stresses automatically. However, for playing slower notes, Dickey must decide to avoid equal stresses and impose a rhythmic flexibility, producing the desired inequality of the notes. The tonguing syllables suggested by Dalla Casa for slower notes do not naturally support unequal note lengths and stresses, but here, Dickey takes the knowledge gained from performing faster notes in the manner discussed by Dalla Casa, combines it with his understanding of the aesthetic goals described in treatises – to imitate speech – and transfers it to the execution of slower notes. The performer benefits immensely from the concepts described in the treatise; however, without the performative experimentation of the musician, an understanding of them would be certainly impoverished. We have spent some time here describing the process of performance as experimentation because it is essential to the way we think about generating soundscape.

As ethnomusicologist Jonathan Shull notes, once the research is completed, the early musician must ultimately decide on a single interpretation, at least for the duration of a particular performance (2006: 97). Following the phases of research and rehearsal, there is a now moment, where consideration ends and the music is. Scholars have the freedom to acknowledge various possibilities and contradictions, whereas performers need to make decisions that will be concretized through performance and recording. It is this concretization of sound – making something ephemeral concrete – that generates a new type of knowledge, one informed by the present and yet rooted in the past.

Our method in creating soundscapes mirrors that of the early music performer, characterized by research and performative process. However, we acknowledge that the depth and nuance of the work achieved by early music performers points to the limits of our analogy – we are not far enough along in the creation of historically informed soundscape to draw conclusions with the depth and nuance of the early music performer. Indeed, written descriptions or visual representations of historical sound are not as informative as a Baroque musical score, yet these descriptions and representations provide us an entry way into the sound of the past. Resonating with Rath’s idea of soundscape serving as a rubric (2008: 428), Jonathan Shull discusses early music director Joel Cohen's approach to the performance of early music; Cohen gives the audience a “hypothesis about [a] piece, hoping that something will come across” (Shull 2006: 99). The idea of providing a “hypothesis” of past sound – one informed by the present and our understanding of sound over time – is precisely what we hope to achieve when creating a historically informed soundscape.

Page one of three of the tenor voice part in manuscript of Laetare Syon by Gasparo Casati (ca 1610-41)

The recording of Corda Deo dabimus by Ercole Porta features the sonority of sackbuts and organ performed by members of ¡Sacabuche! with Nicholas Tamagna (countertenor) and Aaron Sheehan (tenor) (Pearse and ¡Sacabuche! 2015)

Texts Informing Sound

We made a decision to explore Kateri Tekakwitha in our project because she inhabited a space between cultures at a transitional point in history. She became a Christian (indeed she was canonized in 2012) without ever surrendering her Mohawk identity. She is also an appealing subject because we have extensive sources on her: two Jesuits, Pierre Cholenec (1641–1723) and Claude Chauchetière (1701–1740), who knew her well have left extensive accounts. It is clear that they did not quite understand her – a Mohawk woman destined for sainthood seemed to them to be a contradiction in terms – but they wrote extensively about her, and scholars such as Alan Greer (2005) have done important work which enables us to understand the particular context of the Jesuits in New France, which shapes the sources we have on Tekakwitha. For our research on texts, we read the Jesuits’ and other travel accounts. We consulted the documents compiled in the lengthy process of her canonization and read Darren Bonaparte’s book (2009), which seeks to reclaim Tekakwitha as a Mohawk, rather than a Christian, hero. We have also been inspired by Diane Glancy’s work on Tekakwitha (2009).

We consulted secondary sources to learn about how aural historians interpret written descriptions of sound from seventeenth-century America, which reveals both promising and problematic aspects of such texts. Of particular relevance is Edwin Hill’s book (2013) that discusses the sonic significance of the New World through the lens of colonial writings. Building on Mary Louise Pratt's concept of the imperial eye, he proposes the concept of the “imperial ear.” Hill argues that the sonic content in these writings is particularly valuable to scholars in that it allows for new readings of the encounter between colonizers and the New World. Hill writes that European newcomers “often found soundscapes one of the ‘newest’ – that is, ‘strangest,’ most ‘foreign,’ most ‘other’ – aspects of the New World” (2013: 4). He suggests that the “Enlightenment's catalog of the visible” was challenged by the experience of the New World and that sound and soundscapes helped these authors “grasp qualities and characteristics that proved elusive to the visual paradigms of its dominant mode of inquiry, comprehension, and inscription. In other words, techniques and practices of sound, both skilled and amateur, supplement the imperial gaze as they represent distances and forces felt and imagined but unseen and immeasurable in the new world” (2013: 4). Hill’s fundamental insight – that the ways in which sounds and soundscapes are documented plays a significant role in understanding cultural contact between the French and the New World – is a concept our project intends to explore further in an artistic context.

We use insights provided by Hill and Rath, as well as models devised by Schafer, to inform our thinking about sound organization and the meaning of sounds for a subject or community. For example, Schafer developed a system of categorizing sounds that identifies three types: keynotes, background sounds that give shape to foreground sounds, such as water, wind, forests, birds, insects, and animals; signals, foreground sounds that are listened to consciously, e.g., bells, whistles, horns, and sirens; and soundmarks, a community sound that is special to a particular place or community (1977: 9).

Schafer’s system provides a framework that we apply to a historical text describing sound, informing how we make decisions about the use of those sounds in the artistic work. For example, records kept by missionaries provide us with information about how early New France sounded in both ordinary and extraordinary times. One of the most dramatic examples of sound recorded in the Jesuit records is the description of the devastating Charlevoix earthquake, which took place in February 1663:

A noise was suddenly heard under the tranquil and serene sky. At first it sounded as the trumpeter of future disruptions; it seemed to come from afar, and was like the noise of two armies rushing wildly to combat with loud shouts. A frightful crash followed, appearing to proceed from the lowest depths and extreme confines of the earth, and resembling in sound the battle of the waves and the roar of the sea. Then comes a shower of stones, which shatter the roofs of houses and burst into barns, chambers, and the most hidden nooks. Finally the dust rises in whirling columns and forms into a cloud; doors suddenly open and close of themselves; church-bells ring out in token of the general alarm, intoning a doleful chant; the steeples of churches, like tall trees, become the sport of the winds, sway in every direction, and nod their whole height; costly articles are destroyed, furniture is upset, walls are broken asunder, stones become detached, and timbers give way; and all this is accompanied by the bellowing and howling of animals. (Thwaites 1903: 189)

The discussion of the earthquake is framed in religious terms: an indigenous woman meditating had a vision which predicted the earthquake, and the mission itself was not destroyed. But if we listen to the description of the event itself, we can see that sound precedes sight in the description of the event. The sound of the earthquake is described in terms of human sounds (a trumpet, a battle) and then of other sounds of nature (the sea). When metaphorical description stops we hear stones, we see dust, we hear doors opening and closing, we hear church bells, we see – and perhaps hear – church steeples swaying in the wind. Finally, we hear the bellowing of animals.

Taking the example of the earthquake text above, we identify keynote sounds of the tranquil and serene sky and the wind blowing and the sea roaring; examples of signals with “a frightful crash,” a “shower of stones,” and “the bellowing and howling of animals;” and the “church-bells ring out intoning a doleful chant” as a possible soundmark for the area. We will record and perform sounds inspired by this text, creating a sound constellation. For example, we might play recorded sounds of the wind and sea, layer them with performed sounds on instruments that mimic the crash of stones, and include soft whispery sounds made by voices representing the howling of animals.

For our current project, the soundscape contains three elements: recorded soundscape, live created soundscape, and spoken text. We use Schafer’s model to generate the organizational structure. We create a fixed recorded soundscape using keynote sounds, the background sounds – like the wind blowing and sea roaring – taken from the above text. This is layered with the other media, sometimes moving from background (softer dynamic) to foreground (louder dynamic). The musicians (members of ¡Sacabuche! and two Mohawk singer/drummer/dancers) create live soundscape to respond to the text and convey what Schafer refers to as signal sounds. Here the frightful crash, shower of stones and animal bellows will be performed live as a secondary layer of media to the recorded soundscape. Spoken text leads the listener at key points during the recorded and performed soundscape and adds a third media. Although the spoken text does not have a direct correlation with Schafer’s third classification, soundmark, it provides a concrete connection with the historical text and serves to guide the listener in connecting the sounds with the past.

Because the historical texts concerning Tekakwitha are generated by others, they are somewhat removed from her own voice, even when they purport to record direct speech. The soundscapes we create will use the texts which describe her, but will also use other sounds (and silence) to evoke her in a way that supplements the textual descriptions. The soundscapes will also locate her in the changing community of Kahanwà:ke, emphasizing the point that identity is not static.

The opening lines of the song can be roughly translated: “Who can fathom the condition of humankind? One might say that a person seems the opposite of a tree.” The song goes on to talk about how people strain heavenwards for their nourishment, while trees sink roots into the ground. Our decision to commission new music for these seventeenth-century lyrics was very deliberate: we wanted to bring our performance into the present. It was not a nostalgic meditation on the past, but rather an exploration of the ways in which the past might be useful to the present.

In our current project, we are collaborating with two resident Kahnawà:ke musicians and dancers, Owen Mayo (dancer) and Kwena Boivin (singer and drummer). They will perform traditional Mohawk dances, accompanied by drumming, and singing to provide an indigenous voice and context for the segments engaging with Tekakwitha. The methods, material, and structure that they use in their music will be linked with the spoken texts and used to inform our recorded and performed soundscape.

We met Mayo on a visit to Kahnawà:ke; he subsequently introduced us to Boivin. Our visit helped us think about the soundscape in multiple ways. Contemporary sounds of the physical place and environment evoked Tekakwitha in our imaginations, but perhaps more importantly for our project, they suggest the sound of place over time. The soundscape of Kahnawà:ke tells a story of collision and encounters, containing sounds from the past as well as sounds that reflect recent developments the last century or so and interactions between the Kahnawà:ke community and neighboring populations.

We began our work by reading texts and then moved to recording and creating sounds evoked in the texts. For example, the forest was important to Tekakwitha and her cohort of female believers. The Jesuit Cholenec quotes one of Tekakwitha’s peers as saying “At least in the woods I am the mistress of my own body” (Greer 2005: 123). We recorded birds, wind, and water in Kahnawà:ke to evoke the sounds of nature both in Tekakwitha’s time and in the present day. The texts that talk about early New France are quite vivid in their evocation of cold; indeed, a post in Canada was regarded as a special privilege for missionaries because the climate provided strong test of their mettle and their faith. We will evoke the cold through recorded sounds of footsteps on ice as well as musical responses to those sounds by the musicians of ¡Sacabuche!. Both Schafer (1976) and Lowenthal (1976) suggest that the essence of bygone acoustic environments can be experienced by retreating to the countryside or the wilderness; “it is difficult wholly to escape the everyday sounds of modern life […] But today’s natural and rural environments bear at least some resemblance to those of earlier epochs, and by listening to what happens there we can partly recapture the soundscapes of the past” (Lowenthal 1976: 17). We acknowledge that the natural soundscape in Kahnawà:ke now is in no way identical to that of Tekakwitha’s time, but it has strong resonances with the past and serves our artistic purposes in that it allows us to create an aural dialogue between past and present.

We will incorporate segments of recordings we made at the Kahnawà:ke Pow-Wow July 2016 “Echoes of a Proud Nation.” The sounds of singing, drumming, dancing, and people milling about, eating, and talking speak to First Nations People's engagement in an artistic and ceremonial tradition (Blundell 1993). We wandered the grounds on a drizzly gray day, imagining what the area must have looked like when Tekakwitha lived there. We chatted with stallkeepers and bought snacks for sustenance. The pow-wow presents a wonderful mixture of kinds of dances, forms of music, and costuming, featuring both Mohawk and other First Nations people. The quest to find an “authentic” past here would be as futile as the quest to find “authentic” early music. The pow-wow represents a vibrant tradition, with strong roots to the past.

Engaging with Place and the Present to Inform the Past

It is not just Kateri Tekakwitha herself we are interested in; we are interested in the spaces that formed her and the sounds of those spaces. We are engaging with the residents and sound culture of Kahnawà:ke in a variety of ways: collaborating with two Mohawk musicians and dancers, resident at Kahnawà:ke; recording and observing drumming, singing, and dancing; and participating in memory and sound walks with a Kahnawà:ke community member, Davis Rice.

To inform our engagement with people and place, we turn to another set of musical models, that of specialist performers of medieval music. Jonathan Shull talks about how distinguished performers of medieval music “turn to living oral traditions as a sonic, as well as technical, resource for the (re)establishment of new ‘old’ practices” (2006: 88). For the performance of monophonic early music, these musicians look to living musical cultures whose music is based on monophonic song to identify models and techniques of arrangement. They apply these models and techniques to the performance of medieval monophonic song, generating the structure and techniques of arrangement for their performances (100-101). Shull also notes that early music performers of medieval music “hold a firm conviction that living cultures offer a viable opportunity to fill the void left by the inevitable disruptions and discontinuities of the passage of the centuries” (89-90). Granted, there has been widespread criticism of these practices – we cannot know the extent to which past tradition is retained in the present – and of the performers’ attempts to recreate, with any accuracy, past musical sound. However, acknowledging the potential problems with their process, the performers in his study note that the benefits and opportunities outweigh any such concern (96); they assume some continuity and connection with that past. They are more interested in deeper structures and organizational principles of the music than they are with more superficial aspects, such as ornamentation and melodic improvisation. Inspired by these practices, we turn to living oral traditions as a resource for soundscape creation.

We also employ music as a type of sound to inform and create our soundscape. In past projects we have collaborated with musicians participating in continuous past artistic traditions. For example, in our project, Matteo Ricci: His Map and Music, we collaborated with two Chinese musicians specializing in traditional Chinese music performance on traditional instruments: sheng and guzheng. In the Ricci project, the traditional Chinese music provides context, through sound, to inform the life of Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci during his travels in China. It also represents through sound the Chinese literati with whom Ricci interacted (Waltner, Fang and Pearse 2011).

We engaged Chinese-American composer Huang Ruo to compose music for both the instruments and voices of ¡Sacabuche! and the Chinese instruments. His composition sets lyrics composed in Chinese by Ricci to new music. The piece concretizes in sound the interaction between Ricci and the Chinese literati that took place so long ago and at the same time connects it to the present. The lyrics, originally written in both Chinese and Italian to a tune long since lost, represent Ricci’s dual identity.

Davis Rice, our guide, took us to a quiet spot in Kahnawà:ke, where we listened to birds and the wind. He commented that those were the sounds of hundreds of years ago, sounds of the past that we accessed by automobile and captured on recording equipment: one Mohawk, three Canadians and one American, listening to the past.

Because we are interested in the question of the evolution of identity over time and the persistence of communities in the face of European, Canadian and American imperialism, we will use sounds from modern Kahnawà:ke. We hear the sound of cargo ships going through the St. Lawrence Seaway, built by non-native peoples in 1954–1959 to create a sea passage, resulting in a loss of land for the Mohawk people. We hear the sound of cars and trucks barreling over the Honoré-Mercier bridge that bisects Kahnawà:ke and serves as the major route from Montréal to the United States. The undeniable and ever-present sound of air traffic overhead, caused by planes flying in and out of Montréal–Pierre Elliott Trudeau airport, further serves to underscore through sound the impact that European colonizers have had on the First Nations people and its enduring effects. In this case, the soundscape of Kahnawà:ke tells a complex story that has resonances and connections with the distant past while including narratives of the more recent.

We will use our recordings of singing, drumming, and dancing collected at the pow-wow in several different ways. We will tease out sounds and abstract them from the recordings, using them to undergird sections of spoken text. For example, we might use the sounds of conversation and dancing feet behind a text that talks about community in the Mohawk society of Tekakwitha’s day. The rhythm of drumming passages and the cadence and melodic energy of the singing will be used as a model for live soundscape performed by ¡Sacabuche!. Additionally, the recording will blend and interact with live performance by our two Kahnawà:ke musicians, Mr. Mayo and Ms. Boivin.

We will include silence in the soundscape to invoke the solitude which was so important to Tekakwitha. Beyond this, the silence will also gesture to what it is we can never know about her.

My Promises are Above, composed by Huang Ruo for ¡Sacabuche! (2010). The work sets lyrics composed by Matteo Ricci

Sonic Memory and Listening Walks

Another technique we used to collect the knowledge we needed to create the soundscape was to participate in memory and listening walks with a community member in Kahnawà:ke. Upon meeting our tour guide, Davis Rice, we explained that we were interested in Kahnawà:ke’s soundscape and that, while all parties might need to occasionally remain silent to obtain uninterrupted sound recordings, he should freely comment on his surroundings. Guiding our interactions with him are the arguments of Helmi Järviluoma and Noora Vikman about the value of scholars leaving the laboratory and entering the field (2013). Their specific methodological approaches bring the community’s perspective to the forefront in an effort to produce a more nuanced understanding (2013: 2-3). The methods resonate with those of the Medieval music specialists who engage with people connected to continuous musical traditions to inform their models of arrangement and performance of Medieval music. Both processes involve engaging with people of today to find resonance with the past.

Our time with Rice was divided into equal parts: driving and walking. While driving, Rice spoke about Mohawk history, providing forward and frank commentary on a number of historical, political, and cultural issues. In the walking portions, Rice guided us through wooded and uninhabited areas of Kahnawà:ke, with the hopes that these areas would be void of the sounds of industry and human presence.[20]

Mr. Rice’s commentary focused our attention on sounds that resonate with members of the community today and are of importance to their identity over time. He linked sounds of specific locations with events in recent history that are of continuing significance to the community. For example, his focus on the Honoré-Mercier bridge that connects Montréal to Kahnawà:ke and the sounds of ships passing through the St. Lawrence Seaway draws attention to the historical reality of non-indigenous expansion to the detriment of the Mohawk community. In the background, while he is talking, we hear a steady stream of traffic noises. These sounds of the bridge, ships, planes, and traffic connect the present soundscape with that of the past and sonically elucidates narratives of conflict with non-indigenous peoples that are enduring.

In our conversations, we learned that Tekakwitha means different things to different members of the community. Our collaborator Owen Mayo’s grandmother was a devout follower of Tekakwitha, and his upbringing was profoundly influenced by her devotion. Many community members play an active role in the St. Francis Xavier Mission Church that houses the tomb and shrine of Tekakwitha and features the Mohawk Choir singing sacred music set to Mohawk texts. But our guide Mr. Rice made no mention of Tekakwitha, and when we asked him about her significance to the community, he responded that her memory was important only in terms of commerce and tourism.

References

Adorno, Theodor (1983). Prisms (trans. Samuel Weber and Sherry Weber). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Atkinson, Niall (2016). The Noisy Renaissance: Sound, Architecture, and Florentine Urban Life. College Station: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Benjamin, Walter (2006). “On the Concept of History” (trans. Edmund Jephcott). In Howard Eland and Michael Jennings (eds.), Selected Writings of Walter Benjamin, Volume 4, 1938-1940 (pp. 389-400). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Blundell, Valda (1993). “Echoes of a Proud Nation: Reading Kahnawake's Powwow as a Post-Oka Text.” Canadian Journal of Communication 18/3: 333-346.

Bonaparte, Darren (2009). A Lily Among Thorns: The Mohawk Repatriation of Káteri Tekahkwí:tha. Akwesasne, Québec: Wampum Chronicles.

Bovicelli, Giovanni Battista (1594). Regole Passaggi di Musica. Facsimile, Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1957. Originally published in Venice, Giacomo Vincenti.

Brunelli, Antonio (1614). Varii esercutii, edited by Richard Erig. Zürich: Musikverlag zum Pelikan, 1976. Originally published in Florence: Zanobi Pignoni.

Caccini, Giulio (1601). Le nuove musiche. Facsimile, Florence: Studio per Edizioni Scelte, 1983. Originally published in Florence: I Marescotti.

Dalla Casa, Girolamo (1584). Il Vero Modo di Diminuir, con tutte le sorti di stromenti (trans. Sion M. Honea).

Dickey, Bruce (2012). La Bella Minuta: Florid Songs for the Cornetto around 1600. [CD]. Passacaille.

Diruta, Girolamo (1593). Il Transilvano. Facsimile, Bologna: Forni Editore, 1969. Originally published in Venice: Giacomo Vincenti.

Fabian, Dorottya (2001). “The Meaning of Authenticity and The Early Music Movement: A Historical Review.” International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music 32/2: 153-167.

Ganassi, Silvertro (1542). Regola Rubertina. Facsimile, Bologna: Forni Editore, 1970. Originally published in Venice.

Glancy, Diane (2009). The Reason for Crows: The Story of Kateri Tekakwitha. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Greer, Allan (2005). Mohawk Saint: Catherine Tekakwitha and the Jesuits. New York: Oxford University Press.

Harnoncourt, Nikolaus (1980). Interview by Wolf-Eberhard von Lewinski. “Wir hören die alte Musik ganz falsch: Gespräch mit Nikolaus Harnoncourt.” Westermanns Monatshefte 3: 33.

Hill, Edwin (2013). Black Soundscapes, White Stages: The Meaning of Francophone Sound in the Black Atlantic. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hogwood, Christopher (1984). Interview by Gerhard Persche. “Authentizität ist nicht Akademismus; ein Gespräch mit Christopher Hogwood” (trans. John Kehoe). Opernwelt 25: 58-61.

Howard, Deborah (2009). Sound and Space in Renaissance Venice: Architecture, Music, Acoustics. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Järviluoma, Helmi and Noora Vikman (2013). “On Soundscape Methods and Audiovisual Sensibility.” In John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics (pp. 645-658). New York: Oxford University Press.

Le Guin, Elisabeth (2006). Boccherini’s Body: An Essay in Carnal Musicology. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lingold, Mary Caton, Laurent Dubois and David Garner (2016). “Musical Passage.”

Lowenthal, David (1976). “Tuning into the past: can we recapture the soundscapes of bygone days?” UNESCO Courier 29: 15-20.

Pasler, Jann (2007). Writing through Music: Essays on Music, Culture, and Politics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Pearse, D. Linda (2014). Seventeenth-Century Italian Motets with Trombone. Middleton: A-R Editions.

Pearse, D. Linda and ¡Sacabuche! (2015). Seventeenth-Century Italian Motets [CD]. ATMA Classique.

Peri, Alexis (2017). The War Within: Diaries from the Siege of Leningrad. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Rath, Richard (2003). How Early America Sounded. New York: Cornell University Press.

Rath, Richard (2008). “Hearing American History.” The Journal of American History 95/2: 417-431.

Rath, Richard (2014). “Hearing Wampum: The Senses, Mediation, and the Limits of Analogy.” In Matt Cohen and Jeffrey Glover (eds.), Colonial Mediascapes: Sensory Worlds of the Early Americas (pp. 290-321). London: University of Nebraska Press.

Rath, Richard (2014). “Sensory Media: Communication and the Enlightenment in the Atlantic World.” In Anne C. Vila (ed.), A Cultural history of the Senses in the Age of Enlightenment, 1650-1800 (pp. 271-292). London: Bloomsbury.

Ricoeur, Paul (1984). The Reality of the Historical Past. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press.

Schafer, R. Murray (1976). “Exploring the New Soundscape: Pioneer Research into the Global Acoustic Environment.” UNESCO Courier 29: 4-8.

Schafer, R. Murray (1977). The Tuning of the World. New York: Knopf.

Shull, Jonathan (2006). “Locating the Past in the Present: Living Traditions and the Performance of Early Music.” Ethnomusicology Forum 15/1: 87-111.

Simpson, Audra (2014). Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. Durham: Duke University Press.

Small, Christopher (1998). Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Smith, Anne (2011). The Performance of 16th-Century Music: Learning form the Theorists. New York: Oxford University Press.

Smith, Mark (ed.) (2004). Hearing History: A Reader. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

Smith, Mark (2007). Sensory History. New York: Berg Publishers.

Smith, Susan J. (1994). “Soundscape.” Area 26/3: 232-240.

Taruskin, Richard (1982). “On Letting the Music Speak of Itself: Some Reflections on Musicology and Performance.” The Journal of Musicology 1/3: 338-349.

Thwaites, Reuben Gold (ed.) (1903). The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents: Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France 1610 – 1791. Vol. XLVIII: Lower Canada, Ottawas, 1662 — 1664. Cleveland: The Burrows Brothers Company.

Truax, Barry (1984). Acoustic Communication. Norwood: Albex Publishing Cooperation.

Truax, Barry (2008). “Soundscape Composition as Global Music: Electroacoustic Music as Soundscape.” Organized Sound 13/2: 103-109.

Truax, Barry (2012). “Sound, Listening and Place: The Aesthetic Dilemma.” Organized Sound 17/3: 193-201.

Upton, Elizabeth (2012). “Concepts of Authenticity in Early Music and Popular Music Communities.” Ethnomusicology Review 17: 1-13.

Virgiliano, Aurelio (ca 1600). Il dolcimelo. Facsimile, Firenze: Studio per Edizioni Scelte, 1979.

Wall, John N. (principal investigator) (n.d.). Virtual St. Paul's Cathedral Project.

Waltner, Ann, Qin Fang and Linda Pearse (2011). “Performing Matteo Ricci: The Map and the Music.” Ming Studies 62: 1-24.

Conclusion

From our experience of visiting Kahnawà:ke, we reflect on the importance of artists spending time in the subject’s environment. When one imagines things happening in the past, one imagines them in a specific place. Seeing the trees, the rain, the mud, the water of Kahnawà:ke infuses our imaginations of the past with a vividness. But the visit also underscores that the past is past – that the concerns of the community today are very different and that Tekakwitha is variously important to members of the community. Audra Simpson’s assertions that the past is not frozen in time, that Kahnawà:ke is a vibrant, living, changing community were present in our minds throughout our visit (2014).

Thus, in our creation of soundscapes, we draw on a number of methodologies and theories, but we remain grounded in our practice as early musicians who gather information and then experiment to produce historically informed performances. Our information gathering in the creation of the soundscape involves reading seventeenth-century texts, consulting contemporary works of scholarship, and gathering materials from conversations with people in Kahnawà:ke as well as observing the pow-wow. Our reading of theorists like Schafer and historians like Hill and Rath, as well as the work of Atkinson and Wall, have helped us to organize the “earwitness” materials; the work of people like Järviluoma and Vikman provided guidance as we structured our memory and listening walks.

The analogy between what we do as early musicians and what we do as soundscape creators is not perfect. But the ephemerality of sound, which can make historical sound research problematic for scholars, provides us here with an ideal media for engaging with the meaning of sound over time. Early music performers and soundscape researchers inspire our methods. The implementation of these methods makes us rethink our approach and structure; it is not fundamentally the past we are interested in, but the present and the ways in which stories from the past can inspire, provoke, and instigate the present.