Sound installation

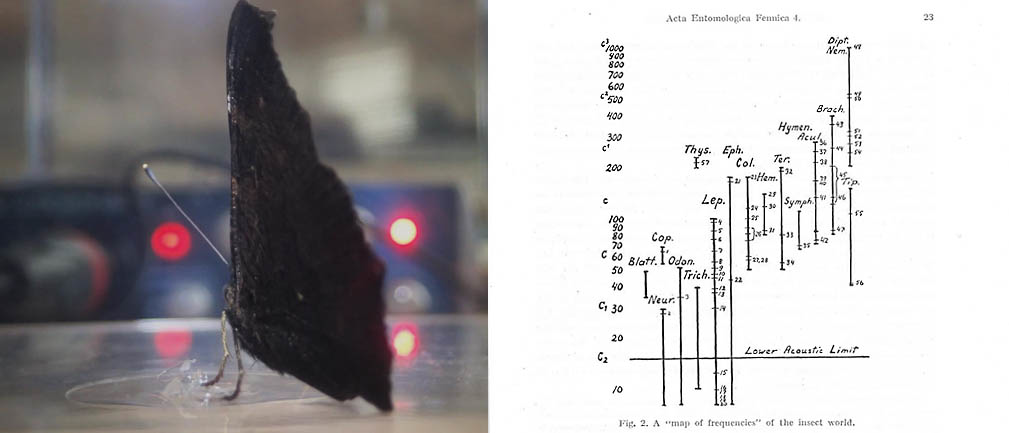

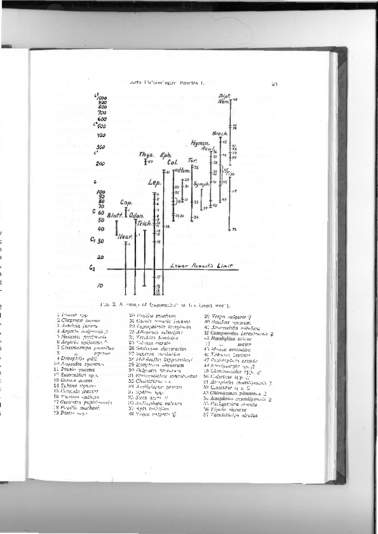

The work is inspired by the Finnish entomologist Olavi Sotavalta, who in a 1952 paper in Nature presented the idea of an auditory approach for identifying insect species.Sotavalta described the uses of his heuristic “acoustic method”. His sensitive ear allowed him to pick up the exact pitch of insects’ buzz and to translate the wing stroke frequency into the tonal register of instrumental music.

The installation is based on reversed binaural audio effect. Audio recordings of flying insects are collected using a pair of stereo microphones faced against each other and placed on opposite sides of the Karaoke Booth (14x14x14 cm).

The buzz produced by the wings was edited and (re)composed by Tytti Arola into ten swinging Wing Beats. The three minute long pieces are played back through headphones. Arola's musical interpretations of the insect sounds create a surreal experience of an insect buzzing inside a person’s head.

Authors:

Tuula Närhinen (Visual artist, DFA) UNIARTS, Helsinki in collaboration with Tytti Arola (sound artist, composer) AALTO University, Espoo

The night after the opening party, Tytti (with the headphones, image on the right) and I launched a performative Insect Karaoke Happening at the Research Pavilion venue. The Wing Beats soundtrack was played back through loudspeakers, and the audience was given simple DIY instruments (thin wine glasses and contact microphones) to join in making music with the electronic insect band. The glasses were played manually by rubbing glass rims with fingers whereas the contact mics were connected to Tytti’s soundcard which manipulated the noises with added effects such as echoes or delays.

Among the audience were researchers from other RP#3 cells such as musicians from Otso Lähdeoja’s ECM band playing their own broken instruments or Esa Kirkkopelto rattling with his homemade tambourines.

“Similarly, wings didn’t suddenly appear in all their aerodynamic glory. They developed from organs that served another purpose. According to one theory, insect wings evolved millions of years ago from body protrusions on flightless bugs. Bugs with bumps had a larger surface area than those without bumps, and this enabled them to absorb more sunlight and thus stay warmer. In a slow evolutionary process, these solar heaters grew larger. The same structure that was good for maximum sunlight absorption – lots of surface area, little weight – also, by coincidence, gave the insects a bit of a lift when they skipped and jumped. Those with bigger protrusions could skip and jump farther. Some insects started using the things to glide, and from there it was a small step to wings that could actually propel the bug through the air. Next time a mosquito buzzes in your ear, accuse her of unnatural behaviour. If she were well behaved and content with what God gave her, she’d use her wings only as solar panels.”

― Yuval Noah Harari, Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind

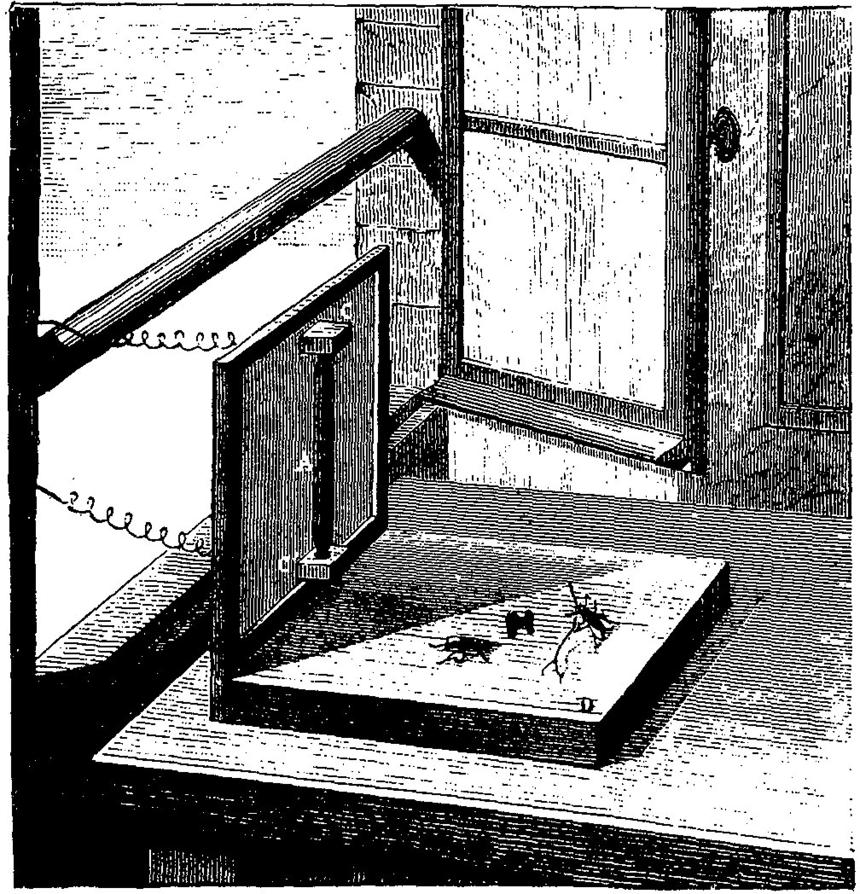

Hughes microphone with recorded fly. The same fly whose footstep was amplified by Hughes's carbon microphone in 1878 to make it audible circles between the left and right channels in Pink Floyd's "Ummagumma."

― Friedrich Kittler, Gramophone, Film, Typewriter, Stanford University Press, 1999. Quote and image from Kittler, p.102

In the PDF (below) a general map and a systematic list of the frequencies of the insect world scanned from Olavi Sotavalta's dissertation (12.7.1947) entitled The Flight-Tone (Wing-Stroke Frequency) of Insects published in the series Acta Entomologica Fennica.