II.IV Discussion

Approach of the study

Visual anthropology is not just the observation of the elements of society that are non-verbal and specifically material, but also the study of society through different visual tools: the eyes of the anthropologist (characterised by cultural elements shaped for a certain vision), their camera and video camera (mediated from their eyes and from their vision), and their hands (with which visual media is created and directed). Starting from these considerations, the methodological goal of my research is to show the potential of painting to express results of anthropological research. This method, that I have called ‘art-tool’, has been used here to show the relationship between people and the world, by starting from an exploration of the cityscape and its inner dynamics.

Urban studies between social change and visual observation

In 1914 the first school of urban sociology, named the Chicago School, was born in the United States. It opened new inquiries that focused on the analysis of human interactions in the metropolitan context. Within this school, Robert Park observed the phenomenon of family conflict and delinquency and noticed that these occurred differently in urban areas compared to rural ones. From this observation he concluded that cultural relations are strongly conditioned by their environment. In addition to the Chicago School, the Manchester School was also fundamental in the development of studies addressing contemporary metropolitan society. Founded in 1947 by Max Gluckman, the concept of mobility was proposed as a useful framework for studying society. A diachronic approach was adopted for the analysis of social realities that were no longer considered immutable structures, but rather places of change. In particular, conflict became the focus of investigation, observed here as the main engine of social change.

Following these studies, the main concepts usually considered by current urban anthropology focus on the analysis of the suburbs, on housing needs, on the integration of immigrants, and on the topics of conflict, delinquency and social participation. Recently, a new specialised branch of studies has been established in Italy that supports the importance of the visual observation of social spaces. This discipline, named ‘ethnosemiotic’, builds on the work of Algirdas Greimas in the field of structural semiotics, which studies the structures and meaning of narrative texts. Its aim is to observe the realities of everyday life as objects of ‘semiosis’, seeing them as places where meaning is built. According to the ethnosemiotic approach, these meanings can be read and translated through the observation of specific forms of space and relationships. The application of semiotics to society and culture demonstrates how certain spatial arrangements can inform the researcher about the state of the relationships that they contain. Using participant observation that is proper of ethnography, with the additional application of the principles of semiotic analysis, a new voice can be given to the observed material. Moreover, my argument is that the visual data, made of shapes, colours, lights, distances, gestures, positions of people and objects in space, can be better represented through visual representation. In order to achieve this, in addition the observation and analysis of the visual data, the use of painting can be useful to express the outcomes of the research, especially in those cases where the studied material is highly visual, such as in the study of space.

Overview of the paintings

To understand the relationship between the individual and the world, we have to investigate the relationship that the person has with the physical space in which they live and the ‘relationships’ that they have with it. Only by understanding these relationships can we clarify the fundamental aspects that form a ‘vision of the world’. In the case of many of today's Western societies, it is through the city and its forms that people build and perceive their existence. Consequently, the observation of the city constitutes a fundamental step in our understanding of contemporary city life. Starting from this, within the paintings shown, I have tried to express my understanding of the relationship between people and the world. To complete this visual section, I will provide here some additional content in relation to two specific topics: loneliness/community and consumerism/resource exploitation. These are the themes that I have developed through study, observation and analysis of the material acquired from extensive participant observations, and personal communications.

From an analysis of the data, I have noticed that many people reference a feeling of loneliness within the crowded city. This feeling is opposed, though in many cases co-existent, to the sense of community. A dualism between loneliness and sense of community seems to be the paradoxical balance on which the existence of people in the city takes shape. The correlated oppositions between private and public, loneliness and community, individuality and crowd, can be seen as the manifestations of two different and converging phenomenological states, which define the condition of being in the world, through the experience of the city life.

While it is useful to collate the feelings and reflections of the participants of my study for discussion, this kind of statistical analysis struggles to convey the raw emotions that lie somewhere just out of tangible grasp, and are not specifically stated or easily described in writing. Nonetheless, these emotions play an integral role in shaping the visions both of my participants and of myself trying to make sense of their words and it is this that I turn to the art-tool method to convey. For example, within the painting ‘City at Night’, I endeavour to portray the dualism between individualism and community that many people have described to me. However, through the medium of painting, here I am also able to link this dualism to the city structures intentionally designed for large-scale consumerism. I also portray my observations of how social and city structures intertwine and the hypocrisy of the private and public spheres. People remain physically separate from the world in their cars and houses but remain superficially linked to one another through their windows. I express here the relentless pace of the city and the hopelessness of individuality. In contrast to this painting, ‘City in Yellow’ explores more deeply the concepts of individuality, loneliness and identity. The figure is contemplating the city that is physically distant, small in comparison to the personality of the individual. Nevertheless, the figure shares the same shape, size and colours of the city, demonstrating the way in which its identity has been formed. Here the distinction of self-determination becomes blurred as urban living inevitably influences the identity making process. This reflects my observations that as people attempt to reinforce their individuality, through clothing, food choices and behaviour, they are inevitably constrained by the city norms and structures within which they create their vision of the world.

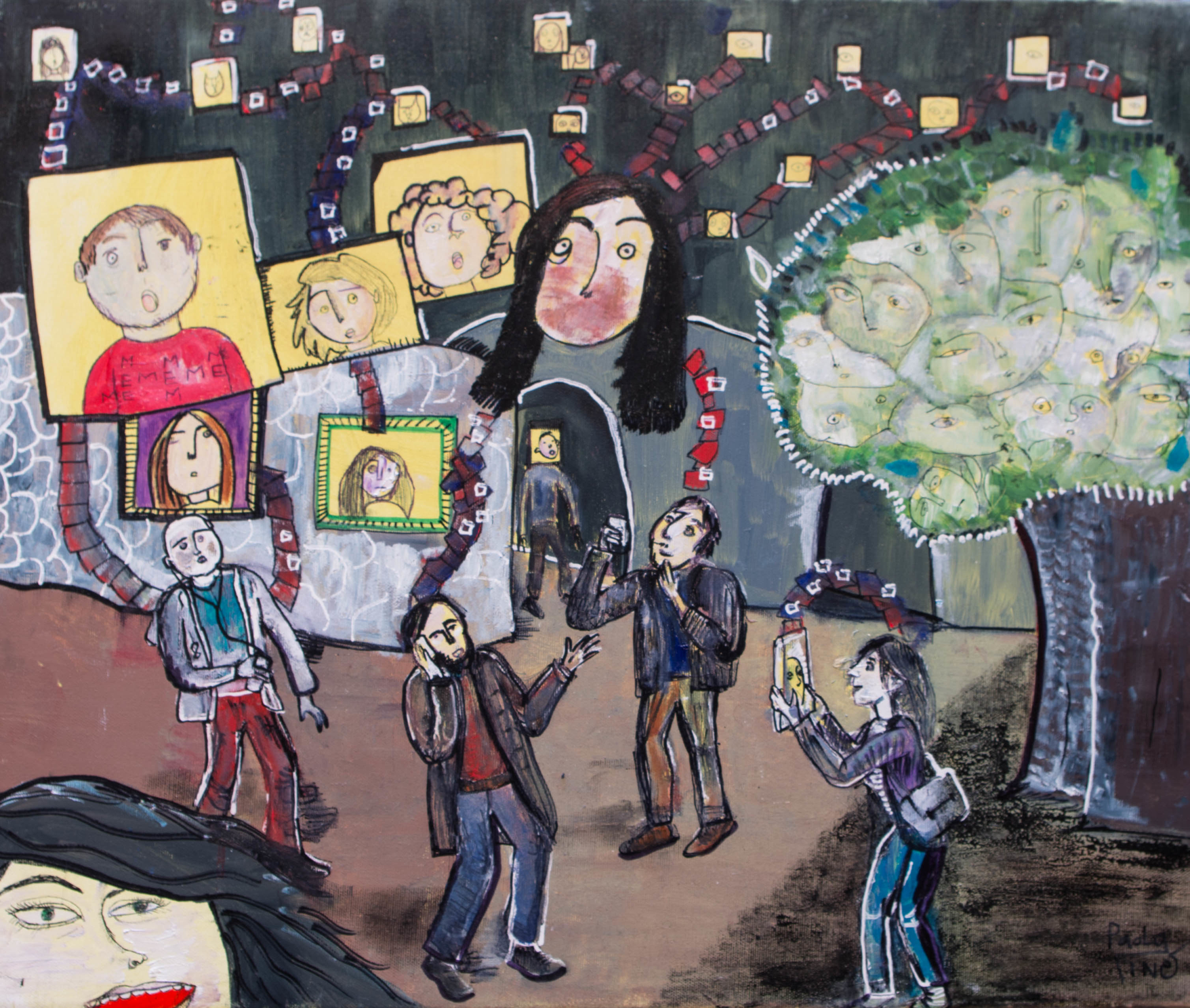

In ‘Shop of the Heads’ and ‘Virtual Relations’ I explore city behaviours in more depth. The former is a dystopian representation, purposefully provocative, that portrays a scene in which people can literally replace their heads in order to appear and think like each other. Through this means, I attempt to describe the absurdity by which many people avoid critical thinking, preferring to take up as their own the opinions imparted on them through media or personal social relations. While people often express their desire to reinforce their own individuality, I have observed that it is rare for people to go against the majority, particularly if this opens them up to criticism. Alternatively, ‘Virtual Relations’ touches upon the emergence of virtual relations, through which superficiality takes precedence and real-life interactions become a thing to avoid. The pictorial representations here both sum up my findings but also provoke emotions in the reader. 'Grow Up in the Crowd' expands further on the concepts explored so far. It shows a child in the lower areas of the painting, walking amongst tall adults. The crowd consists of presences and absences, of unknown people and problems. This painting attempts to portray the realisation of the uncertainty of one’s place in the world. The child in the crowd is a reflection on the loneliness of people and on the potential of children. The paintings are all linked to one another and all the topics have been interweaved in order to reinforce each other.

In relation to consumerism and the exploitation of resources, I have found that some people acknowledge the natural disaster that the world is facing, while others consider do not worry about it at all. I have summarised a prevalent fear for the future in the painting ‘Away from the World’. This also serves to stress the role that community has in this exploitation. The two paintings ‘Big Fishing I’ and Big Fishing II’ reflects on these topics, through the metaphor of an excessive fishing activity. 'Big Fishing' describes a dystopic situation, within which people are falling into a pond from which they have captured a fish that is too big, symbolising the excessive production due to an over-consuming approach to life within contemporary Western society. The catastrophic result is that people are now submerged and wandering in the darkness. The critic of this artwork is not just in the over-production, but in the inhumane animal exploitation that is generally hidden from the public’s eye. A central group of people, surrounded by grocery shopping bags, turn on a candle, breaking the darkness and giving themselves the possibility to see the real extent of the crisis. My impression is that despite being deeply concerned about these issues many people are also afraid to see what is hidden behind the ‘darkness’.

Finally, in ‘Uses and Consumption’, the supermarket is represented as the ironically ‘perfect’ system of consumerism. Every detail in this painting address the hypocrisy of consumption. Starting from the name of the superstore, ‘Super You’, which refers to the importance of a personality that is in reality devoid of any real decision-making power. A recurrent theme concerning the opposition between the queue and the crowd is proposed across many of the paintings but portrayed particularly strongly here. If the crowd is a chaotic version of the community group, the queue represents its ordered and socially constructed version. The queue at the supermarket is the moment when we realise that the world does not belong to us, and that the ‘Super You’ must respect the socially constructed norms of interaction. While we are politely waiting to purchase, we are not anything more than a cog in the communal machinery. The buildings, the city as background, the dump and the pigs are recalled elements from the other paintings, reinforcing the rampant consumerism. I have purposely shown the large amount of rubbish that is physically separated from the shopping district, out of site and out of mind.

II.V Conclusions

In this paper, I have argued that the use of art can be extremely useful for exploring and describing the relationship between people and the world, starting from the analysis of the dynamics between individuals and the cityscape. To achieve this, I have shown examples of paintings on the topic of loneliness and community, consumerism and the exploitation of nature. Through this method, data can be visually displayed, theories can be explored, and emotions can be evoked. The ‘art-tool’ method gives the researcher the opportunity to show others a theory richer and more comprehensive than words alone could ever impart.

<Back to Page 4 - Page 5 - Go to Page 6>