A Fire, a Fight, and a Knight: Elye Bokher in Verse and Song

Elye Bokher (1468 or 1469 - 1549), also known as Eliyahu ben Asher HaLevi Ashkenazi or Elia Bachur Levita, was one of the most highly regarded Hebrew scholars of his era, as well as a poet. Although he clearly wrote other works, only three Yiddish-language poems that can definitely be attributed to him have come down to us. The earliest is the chivalric poem Buovo d’Antona (Padua, completed in 1507, published in 1541), based on an Italian model, but completely transformed according to Jewish-German tastes and tenets and his own artistic vision. It was a work that would, in addition, become one of the bulwarks of Yiddish culture, surviving in prose versions into the 20th century.[1] The two other works are based on German-Jewish metric models (the first with some Italian influence); however, they are firmly anchored on Italian soil: the Sreyfe Lid (Venice, 1514) is a parody, an account of a fire on the Venetian Rialto, while the Hamavdil-Lid (Venice, 1514) a mocking account of a certain Hillel Cohen’s wrongdoings, is clearly set in Northern Italy.

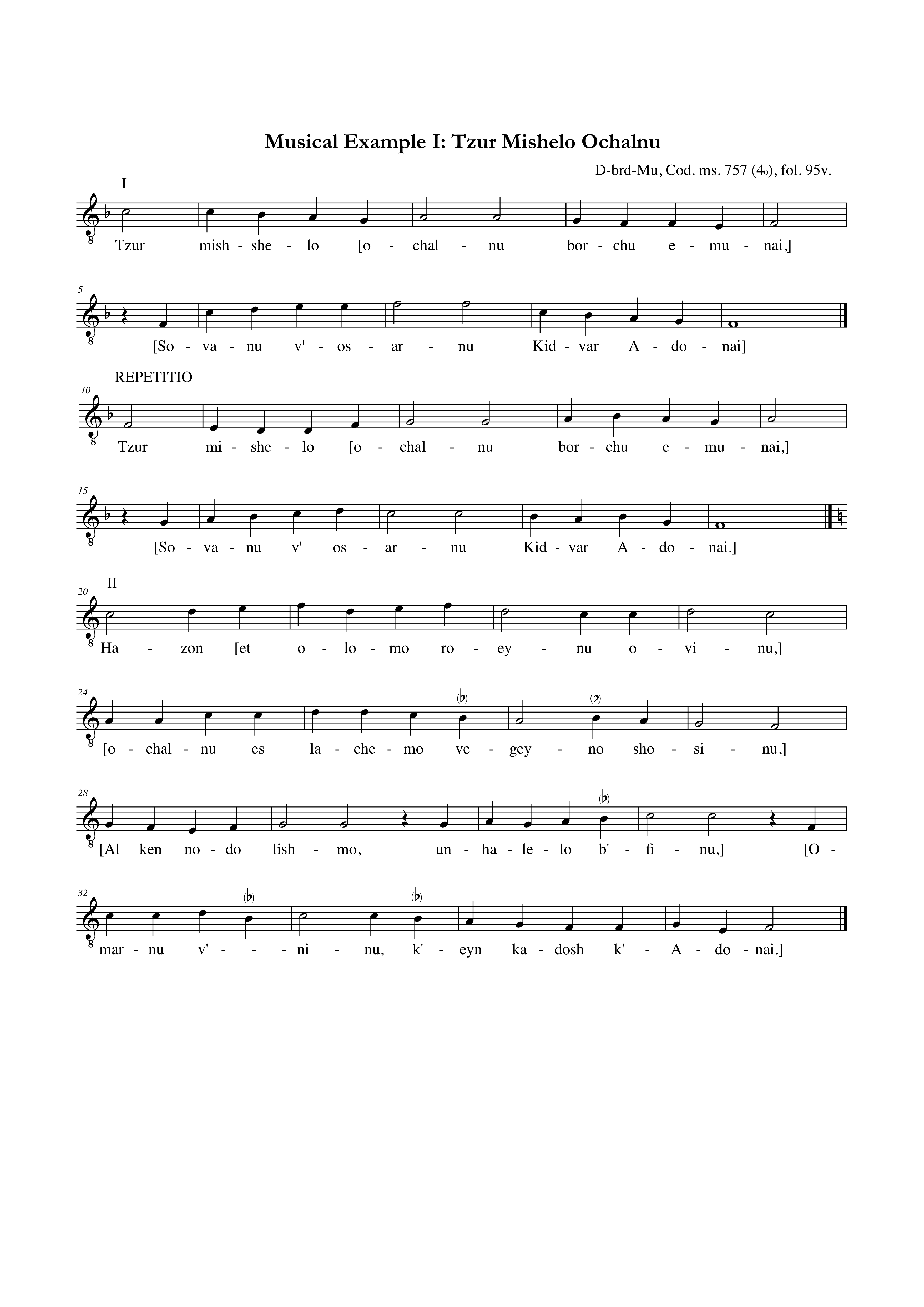

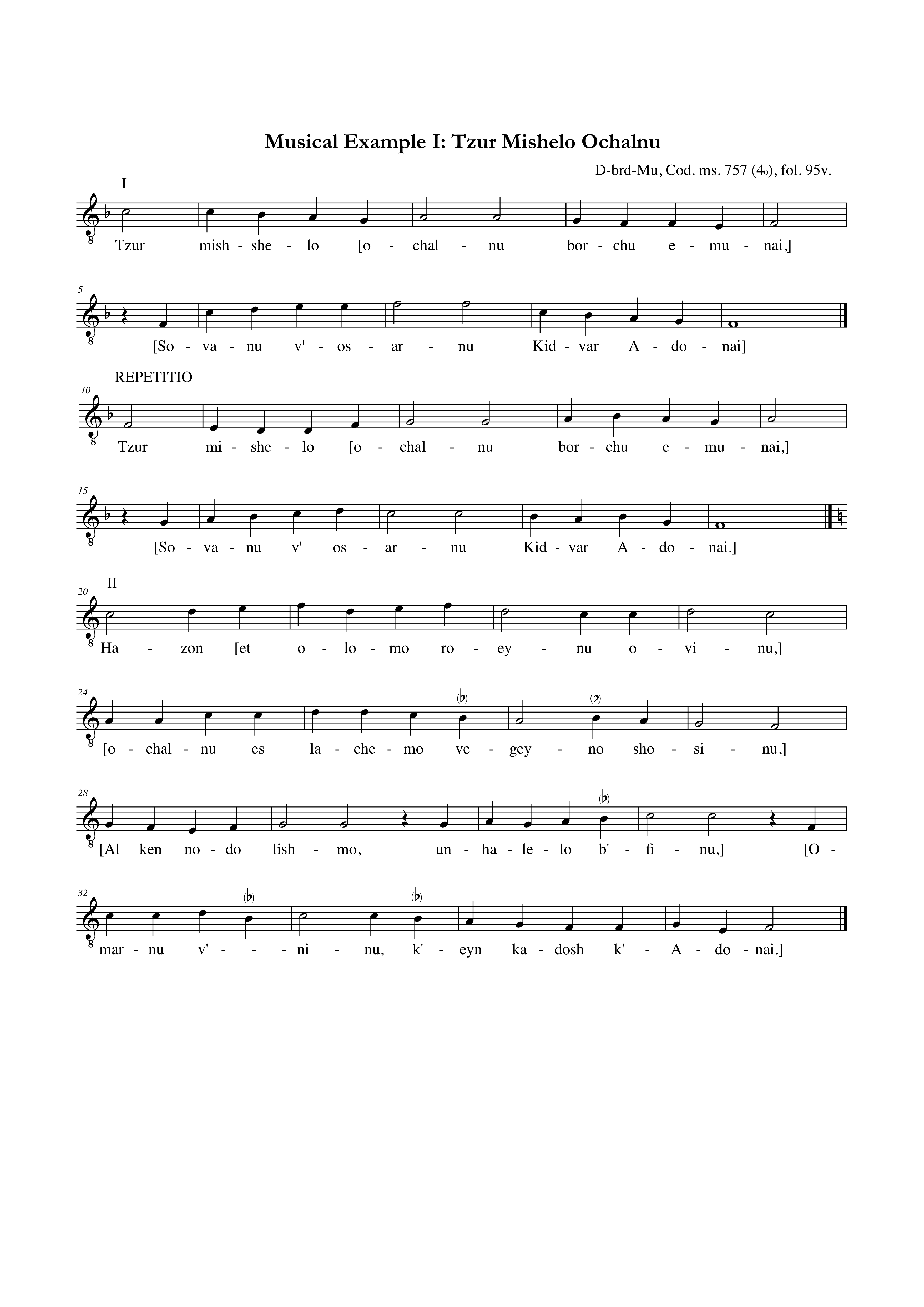

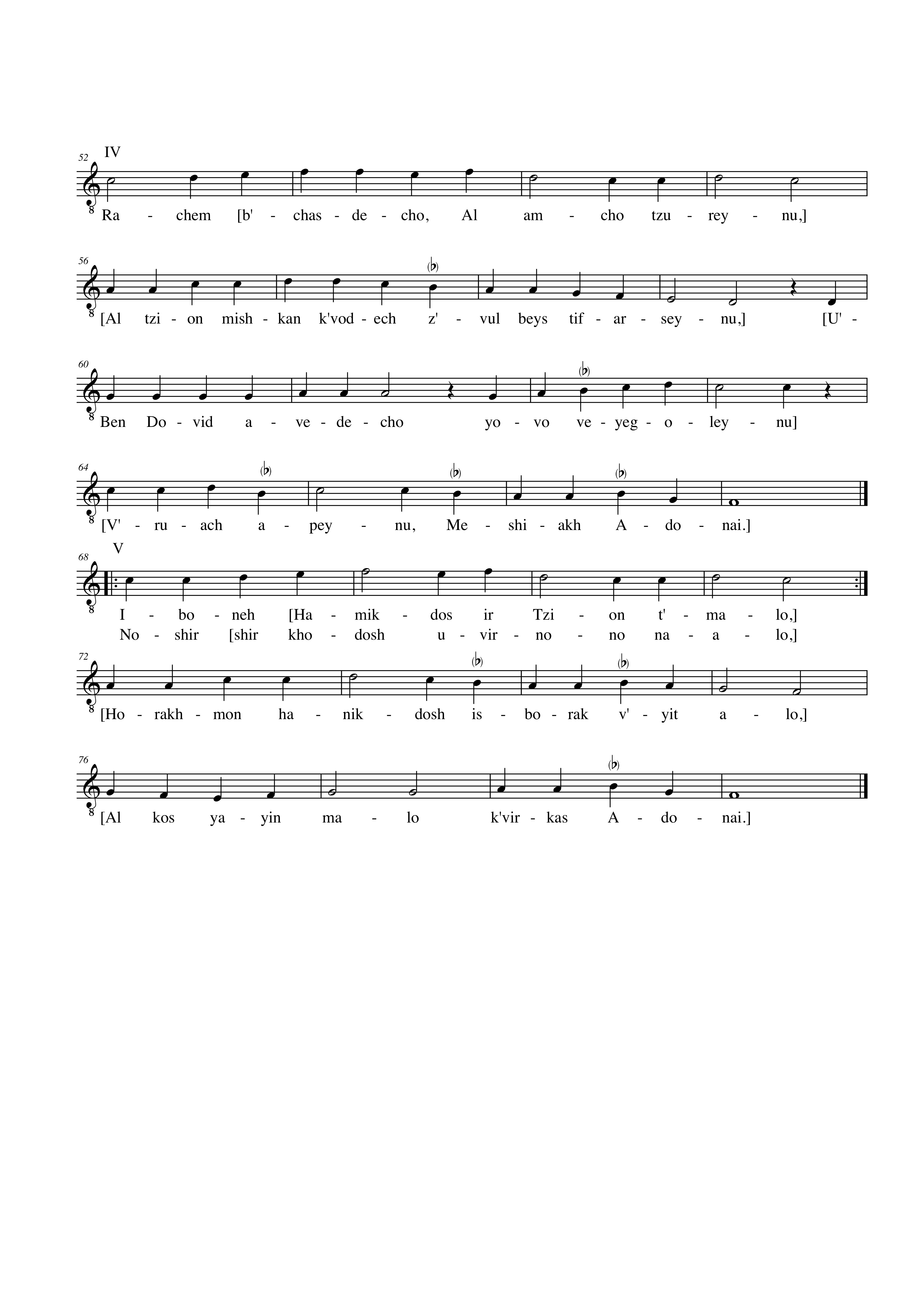

For all three poems, some kind of melodic model has survived, so that there is a possibility of constructing a ‘best guess’ melody for each one, although from different kinds of musical data. In sources, the Sreyfe Lid is indicated as “ayn Lid b’nig’n Tzur Mishelo” – "a song sung to the tune of Tzur Mishelo" – a late medieval piyyut (post-biblical poem in Hebrew) traditionally sung during Sabbath festivities. Almost miraculously, a transcription of a contemporary South German Tzur Mishelo Okhalnu (“The Lord, our Rock”) has survived.[2] Bokher’s Hamavdil Lid is also based on a sung piyyut: Hamavdil bein kodesh le-khol (“The One who Distinguishes between Sacred and Profane”). Here too, a melody has survived, albeit one dating from over 200 years after Elye wrote the original parody: in the third volume of Benedetto Marcello’s Estro Poetico Armonico (1724-26), transcribed as sung by the Ashkenazy community of Venice.[3] A version of the Bovo Bukh with a proposal for a musical setting has already been published in another article,[4] so it will not be included here. However, the poem deserves to be mentioned because it demonstrates the deep penetration of mainstream Italian culture into the lives of the German Jews living there by the use of one of the Peninsula’s most characteristic meters, the ottava rima.[5] Furthermore, it was loosely based on the Buovo d’Antona,[6] one of the pillars of Italian epic poetry, a model that, although originally independent, was later integrated into one of the bases of Italian culture, still sung today in parts of Italy, the Reali di Francia.[7] The ottava is considered the vehicle par excellence for communication, and is used for sung improvisations and storytelling, in particular epic poetry. Dating back to Boccaccio’s time, if not earlier, it has been linked to vocal performance since its origins, and was (and is) used extensively by cantastorie.[8] Although the aim of this article is to discuss two specific cases in which actual Jewish melodic models have survived, this should be seen against the background of the widespread adoption and transformation of Italian verse forms by the Jews living on the Peninsula. During his lifetime, Elye Bokher played a dual role: as ambassador to the Christian intellectual world, and as an influential member of the Jewish community, so that it is inevitable that the dynamics between Jew and Gentile in late 15th and early 16th century Italy shaped his poetry. In turn, the poems themselves, with their mixture of Italian, Jewish and German traits, give important insights into the mechanics of cultural crossover during the same period. With his use of the ottava form, and indications that it was ‘sung to an Italian tune,’ it seems logical to include the Bovo Bukh in the current experiments that aim to reconstruct the sung performance of Early Modern verse based on a comparative analysis of certain strambotti from the late 15th to early 17th century that have survived with musical notation with the traditional ottava rima. The strambotto borrowed the rhyme scheme of the Tuscan ottava, and in some cases, might have been set to melodies inspired by ones drawn from its oral tradition. However, as a short art song transmitted in written form, it fulfilled a different function and was performed in different contexts than the narratives of the cantastorie* .[9]

Elye Bokher grew up in Neustadt an der Aisch near Nuremberg,[10] and moved to Italy around 1492.[11] He lived between Mestre and Venice[12] until around 1496, when, perhaps driven by the growing restrictions for Jews living in the Venice area,[13] or simply attracted to its better living conditions and larger German-Jewish population, Bokher moved to the historical learning center of Padua, home to several Yeshivas[14] as well as one of the oldest and most important universities in Europe.[15] It was in Padua that he would write the Bovo Bukh. In 1509, a war between the Venetian Republic and the League of Cambrai saw much of the Veneto and neighboring territories overrun by its enemies. As a result, the government of the Serenissima issued a condotta allowing refugees to reside in the city, including, essentially for the first time, Jews. The government was particularly interested in letting in German Jewish bankers and moneylenders, in order to protect their capital and to make sure that the poor would have access to economic relief, so that Elye Bokher, after losing everything he owned in Padua, and probably following on the coattails of the wealthy banker Anselmo Meshullam, also fled to the Serenissima. In Venice, he probably worked for the printer Gershon Soncino, writing commentaries on Hebrew publications[16] and Yiddish poems, including the two lampoons mentioned above.

Around 1514, Bokher left Venice, moving to Rome where the ‘Pope’s Jews’ lived under better conditions than in much of the rest of Italy.[17] He worked for Aegidius of Viterbo, named Cardinal in 1518, living in Egidius’s palace for over a decade. He taught Christian intellectuals about Hebrew, Jewish learning, and Jewish mysticism, in particular the Kabbala. In addition to being held in high regard rather than being vilified for his religious affiliation, this might have also been the only period in which Bokher lived with any kind of economic security. This all came to an abrupt end in 1527 with the Sack of Rome. Bokher again lost everything, including his entire library which was destroyed by fire. The last decades of his life (1527-1549) were spent in the Venice ghetto (established in 1516) except for a sojourn in Germany (1540 --1541/2) where he worked as a proof-reader for Paul Fagius, and also published a number of his works for the first time, even some that had lain in manuscript for decades, such as the Bovo Bukh (published 1541).[18]

Bokher was most known for his Hebrew writings (at least during his lifetime), and his fame as a scholar, teacher, author and editor went far beyond the Jewish community: he was held in the highest regard by Christian Humanists from all over Europe, to the point where he was often criticized by Jews for fraternizing excessively with Christians. His works in Loshen Kodesh[19] (Hebrew) and Mama Loshen[20] (Yiddish) differed from one another on multiple levels: in terms of subject matter, style, form, context and target market. In addition, it would be fair to say that they also expressed different aspects of his personality. This is also the opinion of the author of the introduction to the Yiddish epic poem Paris un Wiene (whether the poem itself was written by Elye or one of his followers has long been a subject of disagreement among Yiddish scholars), who writes:

…Elje Beher,

may his name live on forever and never perish:

these are the books, that he brought into being.

In the Holy tongue, he had

six truly fine ones printed…

… how dear do many hold his seforim…[21]

I’m afraid I’m talking too much,

so I will put down his seforim,

to talk about German things.

And thus must reiterate -

who will now create Purim plays,

or stories,[22] or wedding songs?[23]

Who will make whole books rhyme, and write

so that we can, with laughing, make the time go by? [24]

While his works in Hebrew were intended for a crossover market of observant Jews and Christian intellectuals, all educated to the highest level, and almost all, if not exclusively, male, his Yiddish works were a kind of ‘insider’ literature, written in a language and alphabet only an Ashkenazy Jew could understand, and often dealt with specifically Jewish situations. They were destined for both men and women, but especially the latter, because they did not require fluency in Hebrew or much of a formal education. The separation between high and low, between serious and funny, between sanctity and obscenity, were emblematic of the two sides of Elye Bokher.

In passing, it should be noted that there are also instances of Bokher using Mama Loshen in a more ‘serious’ context: many of his Hebrew works had glosses and/or commentaries in Yiddish (and other languages), and 1545 saw the publication of his translation of the psalms.[25] However, it should be pointed out that these were not, strictly speaking, examples of artistic creativity. He certainly wrote more Yiddish poems, but these did not survive. Many might have been composed for single occasions, hence their disappearance, although one, Das bukh der shonen Glukn, is documented in other contemporary sources.[26] As noted earlier, Paris un’ Wiene, although not attributed to Bokher in the original, is held to be his by certain scholars certain on stylistic grounds.[27]

Bokher’s surviving (and reliably identifiable) original artistic Yiddish production can all be dated to a period spanning less than a decade, from the Bovo Bukh’s completion in 1507 to 1514, years spent in Mestre, Padua and Venice, where, as in most of the north of Italy, German Jews made up the majority of the community.[28] Indeed, while Bokher lived there, it was one of the most important European centres of Yiddish literary production and publishing.[29] Bokher’s surviving Yiddish poems were written while he was living in a stimulating environment, surrounded by his countryman, where he could produce ‘insider’ works that would be read, appreciated, disseminated and criticized. While in Rome, he lived in far better circumstances, but probably did not have daily contact with a community of Ashkenazim: in any case, he does not seem to have produced many Yiddish works while there.

The Text Sources

The Sreyfe Lid and Hamavdil Lid are both found in the same two sources. The first, Oxford Bodleian Canonici Or. 12 was a manuscript given by Menahem Katz to his 21-year-old daughter, Serlina, (note the Italianate diminutive) on the occasion of her marriage, referring to her as “born in Venice”. Copied by Kalonimus ben Shimon and other scribes during a period dating from 1553 to at latest 1561, it contains a miscellany of items: a Yiddish translation of the Pentateuch, a minhag (guide to Jewish observances; stories, and poems, including Bokher’s irreverent songs.[30] Incidentally, Serlina’s father’s interest in her intellectual development is demonstrated by a considerable use of Hebrew, and its lack of focus on women’s issues: only 18 of the 274 folios in the book are dedicated to mitzvot nashim - the traditional women’s guide to keeping an observant household. In the other source, Cambridge MS F.12.45, copied around 1530[31] the two pasquinatas found in the opening folios are the only poems, followed by three ‘Mayses’ (stories in prose), Jewish versions of mainstream tales, with a widespread use of Italian words.[32]

Music

At over five hundred years’ distance, it is difficult to decipher the signs that could point to a poem being primarily read (silently or out loud), recited, or performed vocally. Contrary to the 20th and 21st centuries, where we tend to perceive a hard distinction between the terms and concepts of ‘poem’ and ‘song,’ the terms ‘Shir’, ‘Lid’ or ‘Canto’ found in the Early Modern world were fluid terms that meant both. Accounts of the Orlando Furioso being sung to improvised melodies[33] coexist with those about its being read, even, in at least one example, by Jewish girls: in his Precetti d’esser imparati dalle donne hebree, the Italian translator, Giacob Alpron, writes: "Ariosto, the centenovelle, and Amadis of Gaul, or similar profane books, should not be read during Shabbat… in order to avoid their learning about lechery or vain things from them.[34] In the postlude to the Bovo Bukh, Elye Bokher writes “I sing it to an Italian tune, he who finds a better one will find thanks”. This should not be seen as a specific reference to the melody of a specific poem, but as a demonstration of a widespread aesthetic value-system (which is certainly not limited to the Early Modern period) that gave prominence to the expression of the text, and where setting a particular text to a particular tune was not an essential element to its performance. This is also attested to by the wide dissemination of songs in text-only transmission, with and without named melodic models, together with the numerous musical sources of generic arie per cantare…’[35]

Indeed, as mentioned earlier, there have been numerous studies about the art of the cantastoria, declamation, and an entire repertoire of partially or wholly orally-transmitted song that flourished next to the music that survived in notation.[36] There are many references in Jewish writings that demonstrate participation in the practice of singing poetry, such as:

“Because I know you ladies,

Are all kind and devout,

I’m sure you’ll have prepared choice dishes…

There will be sweets, nut brittle and candied almonds,

Malvasia and Muscat wine:

But let me remind you: make sure they’re well chilled—

I’m dying of thirst after all this singing.”[37]

“And I set it to a lovely melody, so that no one should get bored.”[38]

“And so, I hope you will accept, with the usual gratitude of your heart, this small gift, that with respect and humility I give to you, with the pledge, however, that, when the time comes . . . if it pleases you, you will let me hear you sing some of its verses.”[39]

Although all and any of these comments could be simply rhetorical, they do talk about singing within the Jewish community. Some of the characteristics that could point towards the vocal performance of poetry, roughly in order of completeness of data (but not of probability) are:

a) A version of the same text with musical notation is found complete with notation in another source (the largest example in the Jewish community is an early 17th century source, the so-called “Eisak Wallikh songbook”).[40]

b) The poem names a melodic model (like the Tzur Mishelo in the Sreyfe Lid).

c) The poem is a parody of a known song (like the Hamavdil Lid).

d) References to singing are found in the title or text.

e) The poem is found in a ‘songster’ source (one containing the texts of known songs, again like the so-called “Eisak Wallikh songbook”).

f) The poem’s meter is that of a form that was normally sung, such as the ottava rima (the* Bovo Bukh*, the Meghillat Ester in ottava rima) terza rima (Me’on Ha’shoalim, Il Tempio) sonnets (in some cases) or the so-called Shmuel bukh and Bovo bukh tunes.

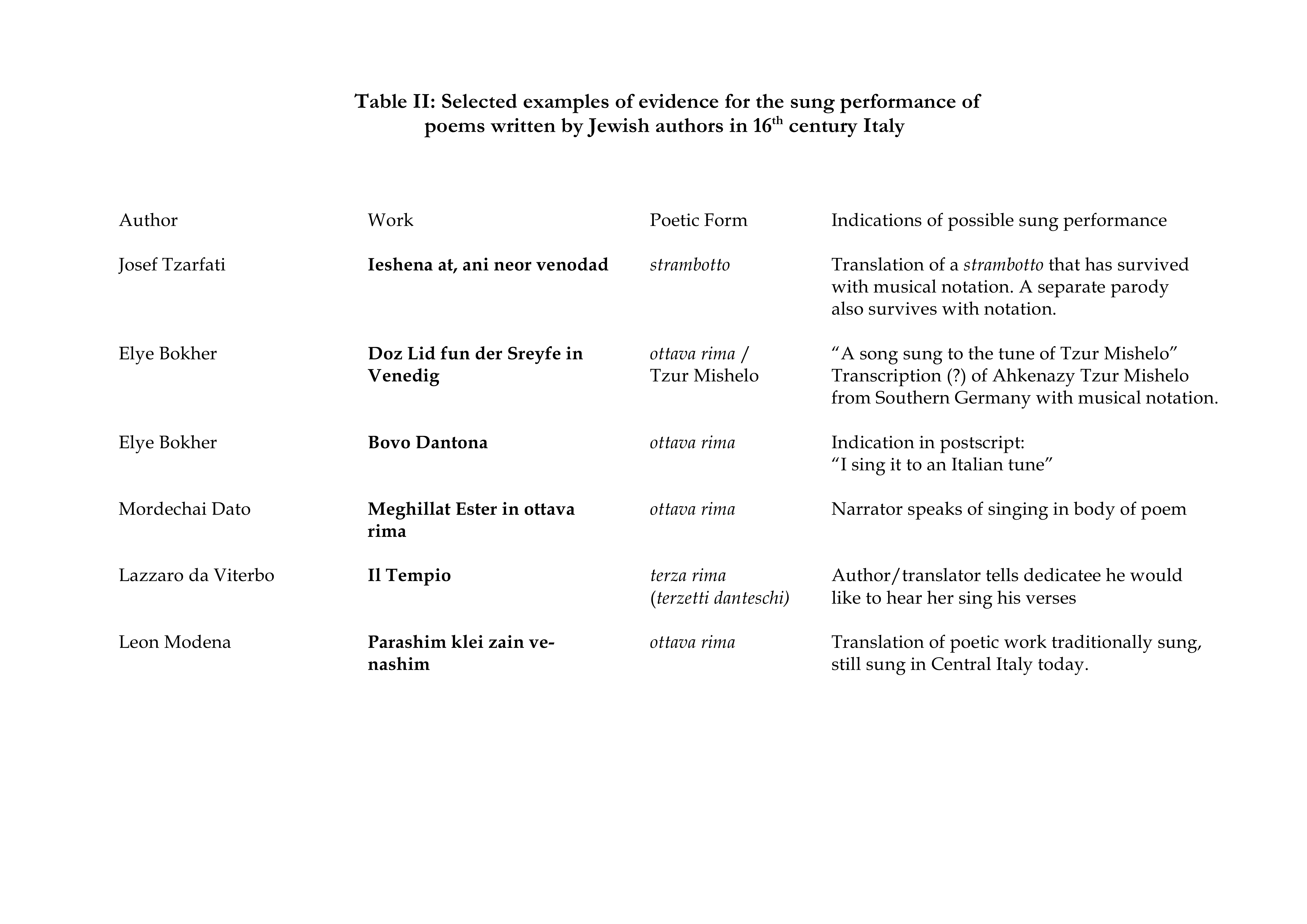

I have included two tables here that give examples of the ‘crossover’ that went on in the Italian Jewish community during the 16th century (Table I) as well as examples of evidence of sung performance (Table II).

Returning to the two Venetian poems, there are, as often, conflicting signals about reading and singing. Claudia Rosenzweig gives a convincing argument that they were originally Pasquinate or Katotoves, a form of public social commentary (often with slanderous intentions) hung up on the walls for all to see [41] Were these ‘wall poems’ recited, sung out loud, or read silently? The answer is probably all of the above, given that these were all forms of expression that co-existed. In any case, the juxtaposition of elements taken from the pious original, like verse form, rhymes, and melody, with a humorous, often disconcertingly vulgar, text, would have meant that even imagining the original melody (and context) while reading would have enhanced the comic effect.

The Cambridge collection is mostly made up of reading material, with stories following the poems. The Oxford miscellanea was destined for a young lady, perhaps as Shabbat reading material, perhaps for singing, perhaps for both. The surprising superimpositions of its content – which ranges from Biblical translations to poems to that talk about carnal relations with children and animals – are hardly what we in the 21st century would see as coherent, nor would we consider it an appropriate gift from a pious father to a nice Jewish girl. Let it therefore be seen as yet another reminder of the enormous gaps in attitude and mentality that lie between the Early Modern era and today.

As an argument for singing, even if the Hamavdil Lid and Doz lid oyf di Sreyfe vun Venedig have come down to us in ‘readers’ sources, they are called songs, and have named melodic models that, as part of the weekly devotional cycle, would have been familiar to all. Rosenzweig writes: “Few texts have survived from the period in which these two songs were written. The fact that both songs have been preserved in two manuscripts, and that these were copied after Elye Bokher’s death, suggests that they must have been quite popular.”[42] This said, the once commonly held supposition that Elye Bokher earned part of his living as a ‘spilman’[43] has since come under criticism.[44] However, there is the possibility that the statement “I sing it to an Italian tune” is not completely rhetorical, and that he, like his fellow Venetian, the highly respected rabbi, poet and scholar Leon Modena (1571-1648) also sang on occasion for financial reward, especially considering his (and Leon Modena’s) often precarious situations. In any case, evidence points to the two poems being widely disseminated, with well-known melodic models, during an era in which poetry was consumed and expressed in many different fashions.

The poems and their music

In the Doz lid oyf der Sreyfe fun Venedig, Bokher portrays the looting that went on in Venice after a fire on the Rialto, in particular the crimes of a certain Hillel Cohen, with the last strophe identifying it as a song for Purim.[45] Claudia Rosenzweig, citing an article by D. Jacoby that pinpoints the date of the fire to January 10th, 1514, hypothesizes that Elye’s poem could well have been in defense of the son of his probable patron, Anselmo Meshullam, who was accused of participating in the robbery.[46]

The work is thirty-five stanzas long in the Oxford source, while sixteen survive (some are missing from the middle and end) in the Cambridge manuscript. In his Early Yiddish Texts, 1100-1750, Jerold C. Frakes points out that two mostly concordant sources have made it possible to put together a critical edition, a rarity with early Yiddish texts.[47]

It is written in ottava rima, a form with which Elye Bokher was certainly familiar. In fact, the influence of the ottava rima went across ‘national’ lines, with examples surviving from the Italian, Sephardic and Ashkenazy communities. These include Mordechai Dato’s epic poem-style setting of the Meghillat Ester in Ottava Rima[48] (Italian in Hebrew characters), Leon Modena’s juvenile translation[49] of selected stanze of the Orlando Furioso into Hebrew; and an anonymous, undated Hebrew-letter transcription[50] of Jerónimo de Urrea’s (1510 – ca. 1570) Spanish language translation[51] of the same Orlando Furioso.

The Sreyfe Lid

The Sreyfe Lid does not use the classic Tuscan ottava rima rhyme scheme (ABABABCC), instead employing a ‘hybrid’ form – ABABCBCX (followed by CDCDCDCX, etc.) – with the ‘X’ rhyme (‘Abonai’)[52] repeated in the last line of every stanza. This kind of ‘girdle’ rhyme, called ‘muwashshah’, was adopted by Jewish poets from Spanish-Arab poetry. The vast majority of piyyutim written in Europe actually followed the Arab-Andalusian tradition.[53] However, there are also many examples of European ‘fusion’ forms that combine East and West, in this case the girdle-form last-line repetition is grafted onto a typical Italianate form.

In the introduction to the poem, Bokher calls it ‘Ayn Lid b’nign 'Tzur Mishelo:’’ “A song sung to the tune of Tzur Mishelo.” The Tzur Mishelo’s rhyme structure is as follows: the ritornello, which is sung twice and repeated after every strophe: AXAX, while the strophes are BCBCBCCX, with the same rhyming syllables (moh/aynu/nay) repeated in the first four stanzas with a variation: DBDBDBBX (dosh/loh/nay) in the fifth and last one. Even if the rhyme scheme is not glaringly different from the Sreyfe lid, its even syllabic count contrasts with Bokher’s poem, which is based on accent and has a syllabic count that varies considerably, as is true of all of his, most Yiddish, and much of the German poetry of the era.

The Munich Tzur Mishelo

A German Tzur Mishelo with music that could be a plausible melodic model was discovered by the musicologist Israel Adler in the Bavarian National Library in 1984,[54] München, 4° Cod. ms. 757, a Hebrew exercise book compiled and copied by Johannes Renhart, finished at some time between 1510 and 1511 in Esslingen.[55] Its structure is made up of a ritornello, where the first four lines (eight hemistiches) of text are repeated twice to different tunes, followed by five stanze, each with its own music. This ‘through composition’ is unusual if not unique, because the normal practice at the time was to set only one strophe to music, and to write the rest of the strophes down in text-only form, presumably under the assumption that a singer would set the rest of the text independently. In the Munich manuscript (see Musical Example I – bars and bar numbers have been added to facilitate reference) each strophe has its own melody, and all are interrelated, with small but significant differences related to text and function. In my opinion, this and other considerations point towards its being an early example of ethnomusicological fieldwork, that, furthermore, might call for a reconsideration as to how strophic song was actually performed.[56] The added or subtracted notes according to accent and syllabic count (compare bars 28, 44 and 59-60), changing contour and final tone in the second line in the internal strophes (m. 24-27: f, 40-43: g, 56-58: d, 72-75: f - see musical example) and the distinctive structure (using pre-existent melodic elements) of the final strophe, which probably heralded the arrival of the last repetition of the ritornello; are all consistent with the kind of changes made during actual performance, as opposed to a transcription made according to the usual constraints of written transmission.[57] In fact, the same kind of melodic transformations can be observed in performances of the piyyut, which has remained in the Jewish tradition, from across the globe.[58]

The unique aspects of the music for the stanze (as opposed to that of the ritornello) of the Munich Tzur Mishelo – the way in which melodies bend and change according to text, function and context, creating a total fusion of poetry and music – also render them unsuitable for setting Bokher’s text. This is why, after much experimentation, the ritornello (msrs. 1-19) which is straightforward, simple, and unchanging, and in turn easily altered to fit the Yiddish text, was chosen to set the Sreyfe Lid.

In the two charts below, the ritornello of the Tzur Mishelo and the first two strophes of the Sreyfe Lid are compared.[59] In the Hebrew model, the lines are regular, each having 7 (first hemistich) + 5 (second hemistich) syllables. In contrast, the Yiddish poem is irregular and organized according to stress (here marked with bold type) with three to each line.

Tzur Mishelo[60]

Tzur mishelo ochalnu 7a

borchu emunai 5x

Sova’nu v’hosarnu 7a

kid’var Abonai 5x

[Tzur mishelo ochalnu 7a

borchu emunai 5x

Sova’nu v’hosarnu 7a

kid’var Abonai 5x]

Sreyfe Lid[61]

Nokh wil ikh oykh ayn vintzig zing’n 9a

Mit mayn’m boyz’n kol 6b

Fun noye g’seh’n ding’n 8a

Di yed’rm’n wis’n zol. 7b

Fun der make un’ der mageyfeh 8c

Di do iz g’wez’n daz dozig mol 10b

Tzu Vin(e)dig in der srey-fe 8c

Asher saraf Abonay. 7x

Ez voz ayn gros’n yam’rn 7d

Az do brent der “Rialt“ 6e

Vun koyf loyt un’ yent’lom’rn 8d

Un vun yud’n yung un’ alt 7e

Yud’n rufn yud’n 6d

D’z zi kem’n b’ld 5e

Un’ vluks grit oyf luydn 6d

Lemaan Abonay 5x

A comparison with our attempt at a musical setting of the first four stanzas of the Sreyfe Lid with the original Tzur Mishelo reflects the consequences of this irregularity, such as added and subtracted notes and multiple syllables added before the first stress (see musical example II).

As said before, the poem is found in two manuscripts: Oxford Bodleian Can. Or. 12 with 55 stanzas, and Cambridge MS F.12.45 with 68 and a half because of a missing folio at the end. Frakes takes the Cambridge manuscript as the source for his edition, writing: “it seems likely that the Cambridge manuscript presents a text closer to the poet’s original composition” citing the number of stanzas as well as their consistency with its “established poetic form”.[62] The Hamavdil Lid is written in quatrains, with a rhyme scheme of AAAX, BBBX, a ‘girdle rhyme’ like the Sreyfe Lid. In this case, the final word of each group of four is ‘layloh’ (night). It uses exactly the same rhyme structure as its model, HaMavdil Bein Kodesh L’Chol, a piyyut traditionally sung at the end of the Sabbath to signify the symbolic separation between the holy (the sabbath day) and the profane (the other days of the week). “Isaac the Younger” is written in acrostic within the poem, pointing to Isaac Judah ibn Ghayyat (Spain, 1030-89) as the probable author,[63] of a poem sung today throughout the Jewish world.[64] Unlike “Tzur Mishelo,” the syllabic count varies widely from hemistich to hemistich, consistent with the Arab-Andalusian tradition as opposed to the more rhythmic Northern European verse.[65]

HaMavdil Bein Kodesh L’Chol

HaMavdil Bein Kodesh l’chol,

Chatoseinu [Hu] yimchol,

Zareinu v’chaspeinu yarbeh kachol,

v’chakochavim b’layloh. [66]

Hamavdil-lid

Hamavdil, bein kodesh lekhol

Tzvish’n mir un’ Hillel den nivzeh knol:

Der da iz hisronoss azo wol:

K’chakochavim b’lay-loh.

Er hot wid’r ayn raym oyf mich gemach’t,

Aber nit vil loyt hob’n zayn gelach’t,

Wen aytil loyg’n hot er gitrach’t

Azo v’rvar zol er nit oys leb’n di layloh.[67]

The Pasquinal is supposedly written in response to a poem by Hillel Cohen which was, in turn, written in response to Bokher’s Sreyfe Lid. In it, Cohen is accused of numerous sins, including being ignorant and unworthy of teaching, a glutton unable to satisfy any of his three wives (all of whom divorce him), of molesting children and animals, having a brother who is a priest, and of being like a Gentile himself. The verses mention cities throughout Northern Italy: Cividale del Friuli, Udine, Portogruaro, Ferrara, Padua, and of course Venice, painting the picture of an environment which was no longer foreign but home to a fusional German-Italian Jewish culture.

As far as melodic models are concerned, we are not as fortunate as in the case of the Sreyfe Lid, where a geographically and temporally appropriate model has survived. Here, although the tune transcribed is indicated as one sung at the German Synagogue in Venice, the model dates from 1724, more than 150 years after Elye Bokher’s death and the compilation of the poem’s surviving sources.

With aspects resembling Gregorian chant, musical and instrumental repertoire from the late 15th and early 16th century, as well as orally-transmitted Chazzonos, the Munich Tzur Mishelo is an exceptional relic, as well as one with the right pedigree: ‘Made in 1510’. In comparison, the Hamavdil tune transcribed by Benedetto Marcello (See Musical Example III) although it is an uncomplicated, and, to use a dangerous adjective, ‘folk-like’ tune, without any glaringly Baroque traits, it does not have a clear heritage, nor can we place it exactly just by analysis or listening. Curiously enough, it is one of the examples transcribed by Marcello that remained in the Jewish-Italian oral tradition until well into the 20th century.[68] Unfortunately, this does not givw us any information about at what point prior to the 1720s this particular tune was composed or adopted. However, whatever its origins, it does express and follow the line, syntax, accent and pitch-height of the text perfectly. The music of the Munich Tzur Mishelo is syllabic, with psalmodic text repetitions on single notes and fixed modal cadential formulas. This is not the case of the Hamavdil. In addition, its embellishments, although quite basic, are organized at different points of the phrase, which means that they do not have the kind of repetitive function – of opening the phrase or heralding the cadence – common to declamation, both in 16th century arie per cantare and in the modern orally-transmitted tradition.[69] Although it is always dangerous to trust our ears in such matters, the melody of the Hamavdil seems have been created around a simple harmonic framework, in any case we can easily imagine a subdominant-tonic-dominant-tonic progression under the melody (the bars have also been kept here for reference, the melody has also been slightly altered from the original) for [ha-to]-sei-nu yimkhol (bars 6-8) or a dominant chord under the repeated Ds on the “chachovim” before the final cadence (bars 15-16). Perhaps a more skilled composer or musicologist might have been capable of producing a more satisfying result, but this author’s attempts at modifying the tune in order to make it conform better in modal structure, cadences and simplifying ornaments to the Munich Tzur Mishelo have only led to an incohesive and unconvincing line that did not match the pitch height or syntax of the text, which is why, with the reservations mentioned above, the tune transcribed by Marcello was deemed the best one to use.

Appendix I: Audio-visual

Tzur Mishelo

Ensemble Lucidarium, live performance at the Musica Cortese Early Music Festival, Gorizia, 2011. Enrico Fink, Gloria Moretti, Marie-Pierre Duceau, vocals.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uim-XWuj8MQ&list=FLe6C0IDQQfEZsxvCN90qtpw&index=7&t=0s

Sreyfe Lid Ensemble Lucidarium, La Istoria de Purim. CD recording, Sarrebourg: K617, 2005. Enrico Fink, Gloria Moretti, Viva Biancaluna Biffi, vocals. Avery Gosfield and Marco Ferrari, recorders. Francis Biggi, cetra. Viva Biancaluna Biffi, vielle. Massimiliano Dragoni, hammer dulcimer.

Hamavdil Lid

Ensemble Lucidarium, Sounds from Shylock’s Venice. CD recording, Abbaye de Bonmont: Ramée / Outhere, in production. Enrico Fink, voice. Dana Howe, lute. Avery Gosfield, recorder.

Appendix II: Facsimiles

Figure 1: “Tzur Mishelo” (text). München, 4° Cod. ms. 757, fol. 95r, upper page.

Figure 2: “Tzir Mishelo” (music). München, 4° Cod. ms. 757, fol. 95r, lower page.

Figure 3: “Sreyfe Lid”. Oxford, Bodleian Library, Ms. Can, Or. 12, 258r.

Figure 4: Salmo Decimosettimo a tre “Diligram te Domine” “Intonazione degli Ebrei Tedeschi sopra ‘המבדיל ונו". Benedetto Marcello, Estro Poetico Armonico, Tomo Terzo, Venezia: 1724, p. 94.

Figure 5:

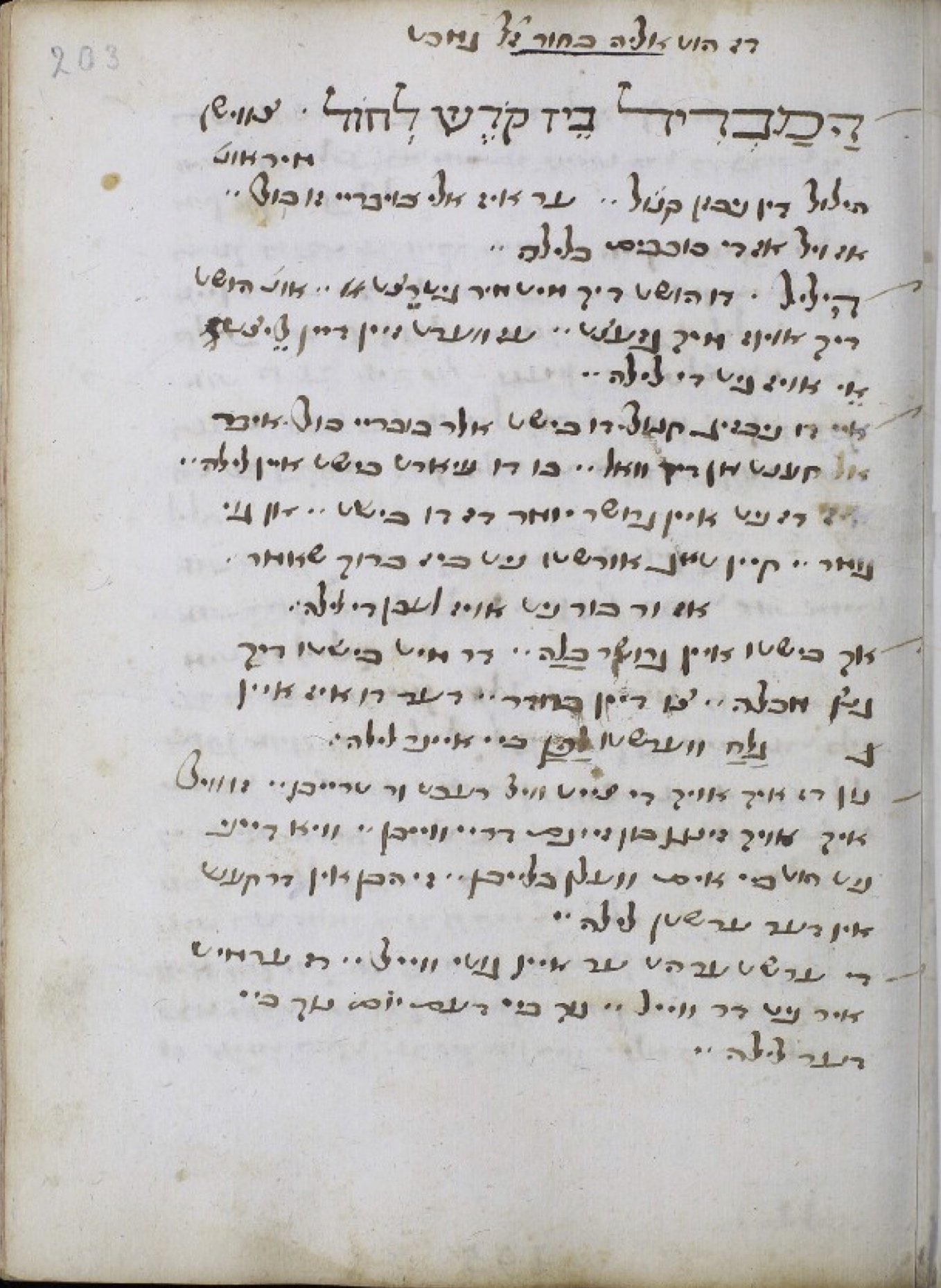

“Hamavdil Lid”. Oxford Can. Or. 12, 203r – 207r.

Footnotes

-

Transformed, it also gave birth to the Yiddish expression “Bubbe Mayses” (grandmother’s tales) that is still used to describe a tall tale today. ↩︎

-

Ms. Universitätsbibliothek der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, 4° Cod. ms. 757, fol. 95r-95v. ↩︎

-

Marcello, Benedetto. Estro Poetico Armonico, Tomo Terzo, Venezia: 1724, p. 94. Called ‘Intonazione degli Ebrei Tedeschi sopra המבדיל ונו’, it is the model for the melody of Salmo Decimosettimo a tre "Diligram te Domini" , p. 94. ↩︎

-

Gosfield, Avery. “I Sing It to an Italian Tune . . . Thoughts on Performing Sixteenth-Century Italian-Jewish Sung Poetry Today,” in ed. Diana Matut. European Journal of Jewish Studies 8, no. 1 (June 25, 2014), pp. 9–52; hereafter Gosfield 2014. https://doi.org/10.1163/1872471X-12341256. Accessed April 1st, 2019 ↩︎

-

A poem of eight lines, each containing 11 syllables. The most widely-used form, the Tuscan ottava, has the rhyme scheme ABABABCC. ↩︎

-

See Delcorno Branca, Daniela, ed. Buovo d’Antona: cantari in ottava rima (1480). 1. ed. Biblioteca medievale 118. Roma: Carocci, 2008. ↩︎

-

The Matter of France, or Carolingian cycle, is a series dedicated to Charlemagne and his followers with roots in the Chanson de Geste genre, transposed into Italian ottava rima at the end of the 15^th^ century. ↩︎

-

Literally a ‘singer of stories.’ In a largely illiterate society (like that of Early Modern Italy), cantastorie played an important role as disseminators of culture. One the mainstays of their repertoire was epic poetry, in particular the poems in ottava rima dedicated to the aforementioned ‘Matter of France.’ Their art was one that cut across social levels, with many performing in both courtly and popular milieus. Parts of the cycle, in particular the Orlando Furioso and Gerusalemme Liberata, are still sung in Central Italy today. ↩︎

-

See: Pirrotta, Nino. Li due Orfei (Torino: Einaudi, 1975); Pirrotta, Nino. “Tradizione orale e tradizione scritta nella musica,” in ed. F. Albert Gallo, l’Ars Nova italiana del Trecento 2, Certaldo: Centro di studi sull’ Ars Nova italiana del Trecento: 1968; Biggi, Francis. “La Fabula Di Orpheo d’Ange Politien ou Comment Rendre Une Oeuvre à l’espace de l’interprétation?” In La Musique Ancienne Entre Historiens et Musiciens, edited by Xavier Bisaro and Rémy Campos. Musique & Recherche 3. Genève: Droz : Haute Ecole de musique de Genève, 2014; Traube, Alexandre. “Traces de Déclamation Dans Les Recueils de Frottole à La Fin Du XVe Siècle: Quelques Pistes Pour Une Recherche.” Ibid; Abramov-van Rijk, Elena. Parlar Cantando: The Practice of Reciting Verses in Italy from 1300 to 1600. Bern, New York: Peter Lang, 2009; Harràn, Don. “Doubly Tainted, Doubly Talented: the Jewish Poet Sara Copio (d. 1641) as a Heroic Singer.” Musica Franca: Essays in Honor of Frank A. D’Accone, eds. I. Alm et al., Festschrift Series, 18 (Stuyvesant, NY: 1996), 367-422; Haar, James. “Improvvisatori and Their Relationship to Sixteenth-Century Music.” In Essays on Italian Poetry and Music in the Renaissance, 1350-1600, ed. James Haar. Ernest Bloch Lectures. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986; Haar, James. “Arie per Cantar Stanze Ariostiche.” In L’Ariosto, La Musica, i Musicisti: Quattro Studi e Sette Madrigali Ariosteschi, ed. Maria Antonella Balsano. Quaderni Della Rivista Italiana Di Musicologia 5. Firenze: L.S. Olschki, 1981; Balsano, Maria Antonella, and James Haar. “L’Ariosto in Musica.” Ibid. ↩︎

-

Rosenzweig, Claudia. Bovo d’Antona by Elye Bokher: A Yiddish Romance: A Critical Edition with Commentary. Studies in Jewish History and Culture, volume 49. Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2016, p.3. Hereafter Rosenzweig 2016. ↩︎

-

A handwritten note by Bokher in the margins of the Qimhi talks about his first son being born in Venice on 9 Elul 5255. See Weil, Gérard. Élie Lévita : Humaniste et Massorète. Vol. 7. Studia Post-Biblica. Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1963, pp. 6 and 29; hereafter Weil 1963; Rosenzweig 2016, p. 3. ↩︎

-

Weil 1963, 6-8 and 30; Rosenzweig 2016, p. 3 ↩︎

-

In his Sefer HaTishbi (The Translator’s Book) he complains about Jews being forced to wear a yellow hat. See Nissim, Paolo. “Le Tappe Del Soggiorno in Italia Di Elia Levita.” La Rassegna Mensile Di Israel, no. Fasc. 8 (1966), p. 5; and Weil 1963, p. 30 ↩︎

-

Educational institutions that specialize in the study of Jewish religious texts. Their main focus is on the Torah, the first five books of the Jewish Bible; and the Talmud, the collection of the Rabbis’ writings dating from before the Common Era to the Fifth Century which is the basis of Jewish law. ↩︎

-

Weil 1963, p. 53-57. ↩︎

-

Rosenzweig 2016, p. 5 ↩︎

-

Rosenzweig, Claudia. Introduction to Levita, Elijah, and Claudia Rosenzweig. Due canti yiddish: rime di un poeta ashkenazita nella Venezia del Cinquecento. Quaderni di traduzione 4. Arezzo: Bibliotheca Arentina, 2010, p. 20, (hereafter Rosenzweig 2010). ↩︎

-

Rosenzweig 2016, p. 9. ↩︎

-

The “holy tongue”. ↩︎

-

The “mother tongue”. ↩︎

-

Seforim, the Hebrew word for books here refers to “holy texts”. ↩︎

-

“Shpruch”, which according to Erica Timm means “short stories that are not sung” footnote to p. 4 in Levita, Elijah, Erika Timm, and Gustav Adolf Beckmann. Paris un Wiene: ein jiddischer Stanzenroman des 16. Jahrhunderts. Tübingen: M. Niemeyer, 1996 (henceforth Timm 1996) ↩︎

-

Bridal songs (Kale = bride). ↩︎

-

Timm 1996, pp. 4-5, Stanza 3, lines 6-8; stanza 4, lines 1,2,7; stanza 5, lines 1-8, translations by the author. ↩︎

-

See Frakes, Jerold C., ed. Early Yiddish Texts, 1100-1750. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008, 179-180 (henceforth Frakes 2008), for example: Sefer HaTishbi (The Translator’s Book, 1541), pp. 189-92; Nomenclatura Hebraica (1542), pp. 254-259, etc. The translation of the Psalms published by Conrad Adelkind was a particularly good seller and was reprinted numerous times. ↩︎

-

Its upcoming publication is mentioned in the colophon of the published version of Bovo Bukh. It is also found in the lists of books given by Jewish families to the censorship authorities in Mantua in 1595, and is given as an example of one of the books not be read in the introduction to Bokher’s own Psalm translations (!). See Rosenzweig 2010, pp. 26-27. ↩︎

-

Timm 1996, pp. CXXXVI-CXXXVII; Rosenzweig 2010, pp. 27-28 ↩︎

-

Shulvass, Moses A. “The Jewish Population in Renaissance Italy.” Jewish Social Studies 13, no. 1 (1951): 3–24. ↩︎

-

Turniansky, Chava, Erika Timm, and Claudia Rosenzweig. Yiddish in Italia: Yiddish Manuscripts and Printed Books from the 15th to the 17th Century. Milano: Associazione Italiana Amici dell’Università di Gerusalemme, 2003, (henceforth Turniansky 2003). They state that the around 80 Yiddish documents, including minhagim (instructional books about Jewish customs), letters, literature and Passover Haggadahs written in Italy have come down to us, are only a small proportion of the thousands (if not tens of thousands) that were probably produced there between the late 15th and early 17th century. ↩︎

-

Rosenzweig 2010, pp. 32-33; Turniansky 2003, pp. 96-99. ↩︎

-

Rosenzweig 2010, p. 146, Turniansky 2003, pp. 108-109. ↩︎

-

Turniansky 2003, p. 108. ↩︎

-

‘…di veder questi contadini il liuto in mano, e fin alle pastorelle l’Ariosto in bocca. Questo si vede per tutta Italia.’ Montaigne, Michel. Journal du voyage en Italie, Par la Suisse & l’Allemagne en 1580 et 1581. Avec des notes-par M. de Querlon. Paris: Le Jay, 1774, vol. 2, p. 292. ↩︎

-

"l’Ariosto le cento novelle, Amadis di Gaula, e simil libri profani, che non è lecito leggerli al שבת come dice משה רבנו è che da quelli non s’imparase non lascività, e cose vane." From: Slonik, Benjamin Aaron ben Abraham. Tr. Alpron, Giacob. Precetti d’esser imparati dalle donne hebree, Venice: Gioanni de’ Paoli, 1710, iii. ↩︎

-

Some examples are G.M. Nanino’s “Aria di cantar sonetti” from Il primo libro delle canzonette a tre voci (Venezia: Angelo Gardano, 1593) or Cosimo Bottegari’s “Aria di Sonetti” from Arie e Canzoni in musica di Cosimo Bottegari (Modena Ms. C311, 1574). Alternatively, the melody of one of the many sonnet settings of the era, especially those with a generic declamatory framework, can be used as a basis for a contrafacta, such as one of the sonetti from Strambotti, ode, sonetti et modo de cantar versi latini e capituli. Libro quarto, Petrucci: Venezia, [1505]. ↩︎

-

See footnote 9. ↩︎

-

“E per che so che voi donni in effetto, tutti benigni e devote seti, so che avereti fatti vivandi eletti, arrosto e a lesso apparecchiato aveti, zuccarini, nociata e confetti, malvasia e moscatel teneti, ma vi raccomondo che sia rinfrescato, che de seta me moro tant’ho cantata.” From Dato, Mordechai, Megillat Ester in Ottava rima in Busi, Giulio, ed., ‘La Istoria de Purim io ve racconto’ . . . Il Libro di Ester secondo un rabbino emiliano del Cinquecento. Venezia: Luis Editore, 1987, p. 107. Henceforth Busi 1987. ↩︎

-

“Aukh hab ikh’s gimakht auf ayn hibsh gizank, Daz eyn’m di wayl daruber nit zal werd’n lang” von Szczebrszyn, Gumprecht. Ms. Budapest, Akadamie der Wissenschaften, Kauffman Collection, Nr. 397, written in Venice, probably 1553–1554, verses 491–492. From Stern, Moritz, ed., Die Lieder des venezianischen Lehrers Gumprecht von Szczebrszyn. Berlin: Hausfreund, 1922. ↩︎

-

“Accetti adunque V.S. con la solita gratitudine dell’ animo suo il picciol dono, quale da me, con riverenza, & humiltà segli porge, con patto però, che quando sera tempo . . . li piacci, che gliene senti cantare qualche verso” From the dedication to Donna Corcos in da Viterbo, Lazzaro, Il Tempio, da M. Moise di Riete, trasportato in vulgare Italiano. Venezia: Giovanni De Gara, ca. 1585. See also Guetta, Alessandro. “Le opere italiane e latine di Lazzaro da Viterbo, ebreo umanista del XVI secolo,” in D’Anruono, Emilia et al., ed. Giacobbe e l’angelo. Figure ebraiche alle radici della modernità europea, Roma: Lithos libri, 2012, pp. 33–34, 46–63. A facsimile of Lazzaro’s Il Tempio can be found at: http://www.hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=42193. Accessed April 10 2019. ↩︎

-

For a model example of song reconstruction of one of the most important sources of Early Modern Jewish music see: Matut, Diana. Dichtung und Musik im frühneuzeitlichen Aschkenas. Leiden: Brill, 2011. ↩︎

-

This tradition goes back to at least the Roman Empire. See Rosenzweig, Claudia. “Rhymes to Sing and Rhymes to Hang Up”. In The Italia Judaica Jubilee Conference, ed. Simonsohn, Shlomo, Shatzmiller, Joseph, and the University of Tel-Aviv. Brill’s Series in Jewish Studies, v. 48. Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2013, pp. 149-53 (henceforth known as Rosenzweig 2013). Using evidence from Bokher’s Sefer Ha-Tishbi, studies by Maks Erik and the poem itself, Rosenzweig places the poems in the Pasquinata / Katovah tradition. ↩︎

-

Rosenzweig continues by saying that because manuscripts were usually produced for local use “Nokhum Shtif argues that they became a kind of folks-lider, folk songs”. Rosenzweig 2013, pp. 148-149; Shtif, Nokhum. Naye material tsu Elye Halevi’s Hamavdil-lid,: Shriftn, I (Kiev 1928), p. 154. ↩︎

-

See Weiss 1968; Erik, Maks. Di geshikte von der yidisher literature fun di eltste tsaytn biz der Haskole-tkufe, Warsaw: Furlag Kultur-lige 1928, reprint: Publications of the Congress for Jewish Culture, New York: Shulsinger Bros. Inc, 1979. pp. 179-202. ↩︎

-

See Rosenzweig 2016, pp. 64-70, in particular pp. 64-65. ↩︎

-

The holiday celebrates the Jews’ salvation at the hand of Queen Esther, wife of King Ahasuerus, and her Uncle Mordechai. It is an occasion for drinking, celebration and theatrics: often (but not exclusively) retellings of the Esther story in the vernacular, and is one of the most important days of the year for Jewish creativity. ↩︎

-

Rosenzweig 2010, pp. 46-48; citing Jacoby, David, New Evidence on Jewish Bankers in Venice and the Venetian Terraferma (ca. 1450-1550) in Toaff, Ariel, ed. The Mediterranean and the Jews. Ramat-Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press, 1989. ↩︎

-

Frakes 2008, pp. 140-141. ↩︎

-

Busi 1987 has a transcription of the entire poem in both Hebrew and Latin letters. ↩︎

-

Oxford, Bodleian, Ms. Michael 528, fol. 55°. See Modena, Leone. The Divan of Leo de Modena: Collection of His Hebrew Poetical Works. Edited from a Unique MS. in the Bodleian Library. Edited by Simon Bernstein. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1932, pp. 33-35. http://www.hebrewbooks.org/pdfpager.aspx?req=37185&st=&pgnum=27&hilite= ↩︎

-

Oxford, Bodleian Ms. Canonici Oriental 6. See Minervini, Laura. “Una Versione Giudeospagnola Dell’Orlando Furioso.” Annali Ca’Foscari XXXII, no. 3 (1993): 35–45. Cecil Roth theorized that it was destined for a Sephard living in Venice. However, in recent years, an origin in the Ottaman Empire has been deemed more probable. Selections from the manuscript can be found at https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/inquire/Discover/Search/#/?p=c+4,t+,rsrs+0,rsps+10,fa+ox%3Acollection^Oriental|ox%3AdisplayLanguage^Judaeo-Spanish,so+ox%3Asort^asc,scids+,pid+58b497ac-bc06-4110-961a-5bfe7d86abf7,vi+ accessed April 10, 2019. ↩︎

-

Ariosto, Ludovico. De Urrea, Jeronimo, tr. Orlando Fvrioso di M. Ludovico Ariosto. Venezia: Gabriel Iolito di Ferrari, 1542. However Minervini states that the second edition, Orlando Furioso… traduzido en Romance Castellano por Don Ieronimo di Vrrea. Antwerp: Martin Nuncio, 1549, was the probable model for the Oxford transcription. ↩︎

-

A substitute for Adonai, because it is the practice among observant Jews that the Lord’s name not be written down, especially in a secular comic song. ↩︎

-

Karmi, T, (pseudonym of Carmi Chamay), ed. The Penguin Book of Hebrew Verse. London: Penguin Books, 2006, pp. 61-65. The Arab Andalusian compositions are much more numerous than any poems based on Western models. Although we know they were sung, no melodic models have survived. ↩︎

-

See Adler, Israel. “The Earliest Notation of a Sabbath Table Song (ca. 1508-1518).” Journal of Synagogue Music XVI, no. 2 (December 1986): 17–37. For more information on the musical notation of the Christian Hebraists in Caspar Amman’s circle see Avenary, Hanoch. “The Earliest Notation of Ashkenazi Bible Chant.” Journal of Jewish Studies 26 (1975) pp. 132–50. ↩︎

-

This information is taken from the website of the UB der LMU München, where the entire manuscript can be consulted online at <https://epub.ub.uni-muenchen.de/22791/>. The extracts reproduced here appear with the permission of the UB der LMU München. Accessed April 10, 2019. ↩︎

-

Gosfield, Avery. “Gratias Post Mensam in Diebus Festiuis Cum Cantico העברײם : A New Look at an Early Sixteenth- Century Tzur Mishelo.” In Revealing the Secrets of the Jews: Johannes Pfefferkorn and Christian Writings about Jewish Life and Literature in Early Modern Europe, ed. by Jonathan Adams, Cordelia Heß, and Uppsala Universitet. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2017, pp. 275–96. Henceforth Gosfield 2017. ↩︎

-

For more information about the melodic variations, see Adler 1986 and Gosfield 2017, they are also clearly visible in the melodic example given here. ↩︎

-

See: http://web.nli.org.il/sites/nlis/he/song/pages/results.aspx#query=any,contains,%D7%A6%D7%95%D7%A8%20%D7%9E%D7%A9%D7%9C%D7%95

last consulted February 17, 2019; and Gosfield 2017, pp. 287-9. ↩︎

-

The poem has been transcribed into Latin letters from Frakes 2008, pp. 141-148. It should be noted that the ‘o’ for aleph and ‘s’ for tav used in the Latin-letter transcriptions of Yiddish here are not the result of an error, but consistent with transcriptions made in German-speaking areas in the 16th century. For more information, see Gosfield 2017. ↩︎

-

The Lord, Our Rock, whose food we have eaten, let us bless Him. We are satiated and there is still food left over, as God has instructed. ↩︎

-

I would like to sing to you a bit, With my poor voice, About some things seen recently That everyone should know about: About the scourge and the plague That happened at the time, When there was a fire in Venice, (That came) by G*d’s hand.

There was a great outcry As the Rialto burned: From merchant and gentleman, And from Jews young and old. Jew called out to Jew To come right away, And, quickly, a cry rang out: ‘For the L*rd’. ↩︎

-

Frakes 2008, pp. 149-150. ↩︎

-

Frakes 2008, p. 150. ↩︎

-

For examples, see Piyyut.org.il, http://web.nli.org.il/sites/nlis/he/song/pages/results.aspx#query=any,contains,המבדיל&indx=21 ↩︎

-

Karmi 2006, p. 63. ↩︎

-

He who makes a distinction between the holy and the profane, May he nullify our sins. May he multiply our offspring and our wealth, like the sand and like the stars in the night. ↩︎

-

This poem has been transcribed from Frakes 2008, pp. 151-164. That which differentiates the holy from the profane, Stands between me and Hillel, that naughty rascal. He that is as full of defects, As there are stars in the night. Once more, he has written a poem about me, But not many people laughed over it, Because he put so many lies in it That he won’t survive this night. ↩︎

-

Seroussi, Marcello. In Search of Jewish Musical Antiquity in the 18th-Century Venetian Ghetto: Reconsidering the Hebrew Melodies in Benedetto Marcello’s “Estro Poetico-Armonico” The Jewish Quarterly Review, Vol. 93, No. 1/2 (Jul. - Oct., 2002), pp. 179-180. The informant is Leo Levy. ↩︎

-

There is an extensive literature dedicated to declamation, for example: Kezich, Giovanni. I Poeti contadini, Rome: Bulzoni, 1986. For more than twenty pages of transcriptions of ottava melodies from the last century, see Maurizio Agamennone’s appendix to Kezich 1986, pp. 171–218. See also Giusti, Maria Elena “Scrittura e oralità nell’ottava toscana,” in eds. Clemente and Fanelli, L’albicocco e la rigaglia. Un ritratto di Realdo Tonti, Siena: Iesa, 2009. ↩︎

-

Gosfield 2014. ↩︎

-

Ensemble Lucidarium. La Istoria de Purim. CD recording, Sarrebourg: K617, 2005. ↩︎