See Twelve Videos

It is not my intention to make a unique interpretation of the information given through the moving images, but to materialize a visual evidence of spatiality performing accidentally. I suggest the images should be received as a sensual provocation before they become an intellectual matter for analysis.

I want to expose the production of visual imagery to underline the materiality of my artistic work. Any experience, action, artefact, image or idea is never definitively just one thing but may be redefined differently in different situations, by different individuals and in terms of different discourses (Pink 2007, 23). In this case, I do not wish to fix any meanings between the sign and the interpreter. Space is no a simple matter and is never just one thing.

Can scenographic spaces perform free from their scenographic origin?

The theoretical knowledge gained from reading research literature in combination with a retroactive observation of the documentation of my scenic work, has conformed an extremely creative process where I have produced new knowledge and alternative procedures to play with space in my professional practice.

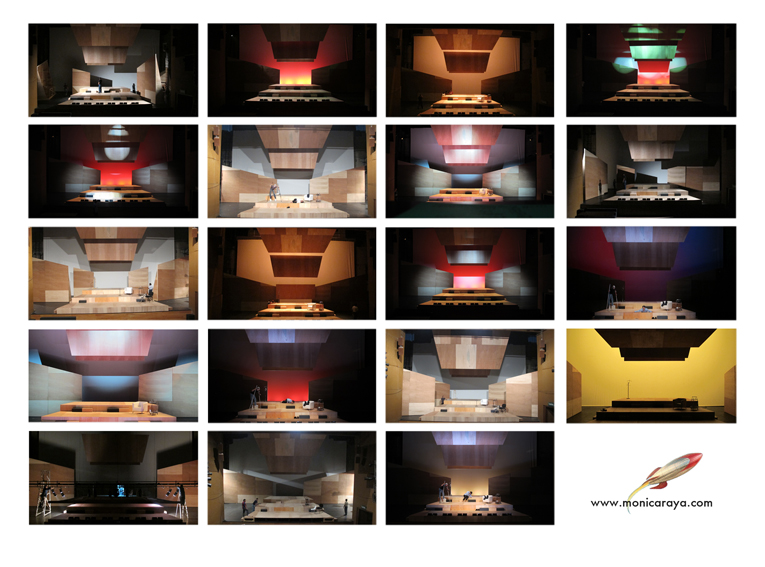

In 2013, I produced a video called Don Gio Love Machine for an OISTAT Symposium in Shanghai and decided to present it again at the 4th Global Conference Performance: Visual aspects of Performance Practice in Oxford. I chose to make a video montage that could work as an experimental text and inform the viewers about the power of scenography playing outside its theatrical conventions. I consider that the visual material works as an open text for representing and interpreting the energy and sensuality of my experience, without translating it into words. I am interested in making attempts to demonstrate how the fusion of the intelligible and the sensible can be applied to scholarly practices and representations (Stoller 1997, xv).

See DON GIO LOVE MACHINE

Alternative thinking

Creating new meanings with visual elements is an open task. As soon as we offer new creative interpretations of a traditional professional practice, we can explore new depths and extensions of the field and expose different possibilities to enjoy artistic work.

Scenography has acted as a test space for my artistic exploration and its documentation generated a retrospective analysis that triggered new questions.

In this research project, I produced photo and video materials where scenography showed a state of liminality: a ‘new condition…a phase of transition…a period of ambiguity’. According to anthropologist Victor Turner ‘Novelty emerges from unprecedented combinations of familiar elements’ (1982, 27-32).

New interpretations of visual culture may contribute to the generation of extended knowledge. New insights about well-known concepts may provoke different outcomes, some of which may go beyond the basic concepts of the discipline of origin.

I am interested in sensuality as an object of analysis and reconsideration of human experience. I am excited to engage with the visual, not simply as a mode of recording data or illustrating texts, but ‘as a medium through which new knowledge and critiques may be created’ (Pink 2007, 13). I propose to connect various sources of knowledge in a way that brings alternatives to think as an architect, as a scenographer, as performance designer and as a teacher.

The knowledge produced by my research suggests a very complex landscape for scenography that it is still hard to define and contain. My spatial work may provoke some curiosity among other designers and might open new debates about scenic practice.

I would like to propose that playing with scenography and the visual documentation of performance design may create new spectacles on its own right and a vehicle to go beyond the borders of a stage as a site for human performers. Alternative thinking on scenography ought to recognize that stage spatiality may perform without the input of scenic directors or deliberated designer actions. It also means that it is possible to produce new materiality for space. Video may also contribute to the understanding of a performing spatiality. It may encourage or inspire readers (Ibid., 152).

Artistic research has provided a process of self-examination and offered ‘the spontaneity and vividness of an interrupted stream of information (Barnes et al., 1997). Documenting scenography revealed the existence of unexpected ephimeral spaces. It also showed the hidden performance of others than actors.

Can we play with the visual documentation of scenography and create an alternative artistic experience?

Is it possible to consider video as a new site for multi-interpretations of performance design?

Can visual materials provide a starting point for new inquiries and a place to re-vision the potential of scenic spaces?

You may want to listen, see, take or allow what space is fully expressing in order to make contact with an organic existence that is part of the universe. And, when I say this, I suggest that designing spaces may be a matter of relating openly to the unpredictable forces of the universe more than to the fiction of the theatrical conventions. Real art has the capacity to make us nervous. If we would like to reduce the work of art only to its content, we are taming the work of art (Sontag 1961, 8).

Space is the primordial body that houses our bodies. I believe that space communicates, in a natural-cosmic way, through our human (physical and social) perception. I think that there is a possibility to establish an alternative dialogue with space before, during and after we work with it. I suggest that thinking that space may be an organic body that breathes like a living creature may increase our awareness of its potential. We may want to start treating it with love and respect.

References

Barnes, D.B., Taylor-Brown, S. and Weiner, L. ‘I didn’t leave y’all on purpose’: HIV-infected mothers’ videotaped legacies for their children’, in S. J. Gold (ed.), Visual Methods in Sociological Analysis, special Issue of Qualitative Sociology, 20 (1). 1997

Butterfield, Jan. The Art of Light and Space. New York: Abbeville Press, 1993.

De Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. Trans. Steven Rendall. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1984.

Golffing, Francis, trans. The Birth of Tragedy and The Genealogy of Morals. New York: Anchor Books: Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, 1956.

Holloway, Lewis. “Donna Haraway.” Hubbard, Phil, Rob Kitchin and Gill Valentine. ed. Key thinkers on Space and Place. London, Thousand Oaks and New Delhi: SAGE Publications, 2004.

Koyré, Alexandre. From the Closed World to the Infinite Universe. Baltimore and London: The John Hopkins University press. Publications of the Institute of the History of Medicine. Third Series: The Hideyo Noguchi Lectures. Volume VII. 1957.

Laakso, Harri. “Imaginary Research.” Mäkelä Maarit and Sara Routarinne ed. The Art of Research: Research Practices in art and design. Finland: University of Art and Design, 2006.

Lefebvre, Henry. The Production of Space. Trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith. Massachusetts, Oxford, and Victoria: Blackwell Publishing, 1991.

Mäkelä, Maarit. “Framing (a) Practice-led Research Project.” Mäkelä Maarit and Sara Routarinne ed. The Art of Research: Research Practices in art and design. Finland: University of Art and Design, 2006.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. Trans. Collin Smith. London and New York: Routledge Classics, 1962.

Pink, Sarah. Doing Visual Ethnography: Images, Media and Representation in Research, 2nd ed. London, Great Britain: Sage, 2007.

Scrivener, Stephen. “Visual Art Practice reconsidered: transformational Practice and the Academy.” Mäkelä Maarit and Sara Routarinne ed. The Art of Research: Research Practices in art and design. Finland: University of Art and Design, 2006.

Sontag, Susan. Against Interpretation and Other Essays. New York: Picador USA. Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1961.

Stoller, Paul. Sensuous Scholarship. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997.

Summatavet, Kärt. “Tradition, Inspiration and Artistic innovation” Mäkelä Maarit and Sara Routarinne ed. The Art of Research: Research Practices in art and design. Finland: University of Art and Design, 2006.

Turner, Victor. “Liminal to Liminoid, in Play, Flow and Ritual. An essay in Comparative symbology” From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play.New York: PAJ Publications, 1982.

VIDEO MATERIALS

-

Austera Matemática Teatral Don Giovanni Toma Blanca https://vimeo.com/44672921

-

Austera Matemática Teatral Don Giovanni Movimiento 0 Preset https://vimeo.com/85373875

-

Austera Matemática Teatral Don Giovanni Movimiento 3 https://vimeo.com/44480806

-

Austera Matemática Teatral Don Giovanni Movimiento 4 https://vimeo.com/44323026

-

Austera Matemática Teatral Don Giovanni Movimiento 6 https://vimeo.com/44325741

-

Austera Matemática Teatral Don Giovanni Movimiento 7 https://vimeo.com/44417561

-

Austera Matemática Teatral Don Giovanni Movimiento 8 https://vimeo.com/44333078

-

Austera Matemática Teatral Don Giovanni Movimiento 9 https://vimeo.com/44683339

-

Austera Matemática Teatral Don Giovanni Movimiento 11 https://vimeo.com/44392304

-

Austera Matemática Teatral Don Giovanni Back https://vimeo.com/85367967

-

Austera Matemática Teatral Don Giovanni Luz y Movimiento https://vimeo.com/44421635

-

Don Giovanni o el disoluto absuelto. Mónica Raya (OISTAT Shanghai 2013) https://vimeo.com/71605538

-

Documental Toma Blanca Don Giovanni https://vimeo.com/85471836

See Video Blanco

Excited and surprised by the beauty of the unexpected performance, I asked photographer and collaborator Andrea Lopez to help me make a particular set of videos. I decided to make an alternative scenographic libretto and document every scene change under the projection of the light cues I had pre-recorded for the show. I also asked permission from the producers and technical support from the theatre crews.

Ten sets were recorded in twelve videos, each video containing 40 different light cues and their transitions. Dozens of new spaces performed as if an enormous sleeping creature was waking up. It was as if the created spatiality had had a chance to liberate from its original purpose and was enabled to manifest its hidden potentiality. It ‘breathed’ like a living thing.

A new libretto called AUSTERA MATEMATICA TEATRAL (Austere Theatrical Math) allowed the space to present a sort of intimate logic. The videos play in silence and each one of them lasts 8 minutes.

Mónica Raya

Space matters: Alternative thinking about the nature of space.

Abstract

I would like to present my inter-textual reading of some theories concerning the nature of space and my reflections upon the materiality of it. I aim to open an alternative way to think about scenography. I would like to expose the theoretical process, the visual documentation and the artistic outcomes of a particular scenic event .

So far, I have used my artistic practice as a method of inquiry and it is not my interest to offer an objective approach to the knowledge of space. In my process, I have found that reflective practice has been a central productive mode for my creativity. I intend to evaluate the unintended and unexpected findings in my work, and make them available for other practitioners.

New interpretations of visual culture may contribute to the generation of extended knowledge. New insights about well-known concepts may provoke different outcomes, some of which may go beyond the basic concepts of the discipline of origin.

I am interested in sensuality as an object of analysis and reconsideration of human experience. I am excited to engage with the visual, not simply as a mode of recording data or illustrating texts, but ‘as a medium through which new knowledge and critiques may be created’ (Pink 2007, 13). I propose to connect various sources of knowledge in a way that brings alternatives to think as an architect, as a scenographer, as performance designer and as a teacher.

As much as I would like to situate the outcomes of my artistic research in the field of performance design, I hope my reflections may cross several disciplines.

Introduction

I am a Mexican architect that has worked in the field of performance and scenic design for nearly 25 years. As a designer, I have produced more than a hundred shows according to the conventional practice but as a researcher I began to concentrate my attention on the ‘behaviour’ of spatiality. My curiosity about the potential of space was awakened while I was studying for my degree. I became a scenographer in order to design and build spaces that have the potential for multiple interpretations.

A few years ago, I decided to undertake artistic research in the hope of gaining insight into my scenic practice. This has led me to question the true nature of space and the paradigms we use to manipulate it.

During the years, I learnt to value the work of designers on the stage but I found my inspiration in the work of artists like Malevich or El Lissizky, Robert Wilson, James Turrell, Robert Irwin, Bruce Nauman or Olafur Eliasson. I am fascinated by the work of artists that have been categorized as experiential, situational, phenomenal, phenomenological, site-specific, ambient or simply Light and Space artists (Butterfield 1993, 9).

In this article, I would like to present my inter-textual reading of some theories concerning the nature of space and my reflections upon the materiality of it. I aim to open an alternative way to think about scenography. I would like to expose the theoretical process, the visual documentation and the artistic outcomes of a particular scenic event.

So far, I have used my artistic practice as a method of inquiry and it is not my interest to offer an objective approach to the knowledge of space. In my process, I have found that reflective practice has been a central productive mode for my creativity. I intend to evaluate the unintended and unexpected findings in my work, and make them available for other practitioners (Scrivener 2006, 177).

I have to admit that my practice expanded dramatically after I started doing artistic research. New knowledge came to enlighten my artistic experience and helped me rearrange previous knowledge. Artistic research has made me discover an area of intellectual and artistic inquiry that I can really call my own.

As I mentioned before, this article attempts to provide an alternative way to think about space and scenography. My research process includes reading, reflecting, observing, playing and making. The experience of writing is completely new, a space of creation I have never tried before.

The task of a scenographer is to design spaces that trigger the imagination of the spectator into an act of perceiving, even the invisible. I believe that doing research about the performance of space can be considered a transformational practice. Research is a ‘turning and finding process’ (Laakso 2006, 144-145) and emerges, not in name, but in action (Scrivener 2006, 164).

As much as I would like to situate the outcomes of my artistic research in the field of performance design, I hope my reflections may cross several disciplines. Robert Irwin suggests that investigations may be even more important than tangible works because they offer ideas before the condensation of a finite form (Butterfield 1993, 16).

Several philosophers suggest that space is indiscernible. My approach to theory, and my own thinking is based on my personal experience of scenic design and it cannot be considered objective knowledge. I am offering my experience as a comprehensive method of thinking-and-working based on creativity and self-criticism. I also find that my experience is not separable from my cultural context as a woman and as an artist. I find it important to reflect upon Donna Haraway’s critique of scientific objectivity. She argues that science is meant to create a mythical objectivity external to social conditions and that these ideas also perpetuate a distinctively masculinist and exploitative understanding of the world. Haraway is concerned to maintain a sense of the materiality or corporeality of nature. I agree that situated knowledge should take responsibility of what we ‘see’, for how we have learned to see, and for our action in the world. (Holloway 2004, 167-170).

In this article, I consider myself a mobile and embodied knowing subject (Mäkelä 2006, 66-68) and I aim to create a dialogue between my observations and interpretations and the theories that are concerned with the nature and performance of space.

I have started with an open dialogue between concepts exposed by ancient, modern and posmodern theoreticians: Nicholas de Cusa, Giordano Bruno, René Descartes, Isaac Newton, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Michel De Certeau, Henry Lefebvre and Victor Turner, among others. My theoretical research provides different readings of the nature of space.

What is space?

According to Professor Alexandre Koyré, in his lectures named From the Closed world to the Infinite universe, it was Nicholas de Cusa, the great philosopher of the Middle Ages, who first denied the finitude of the world and its enclosure by the walls of the heavenly spheres. De Cusa’s conception of the universe was not infinite but interminate, and it was not terminated but indeterminate. He argued that the universe could not be the object of total knowledge and that it was impossible to build a univocal representation of it. He also assured, that the universe was a perfect expression of God and a unity that embraced not only the different but even the opposite qualities of being. (Koyré 1957, 6-9). It was also De Cusa who first exposed the relativity of the perception of space. He asserted that the world-image of a given observer was determined by the place she occupied in the universe; and since there was not one place that can claim an absolutely privileged value, we had to admit the existence of different equivalent world-images and the impossibility of forming an objective representation of the universe. (Ibid., 16-19).

Copernican astronomy demonstrated that the earth was not the centre of the cosmos and placed it among the planets and Giordano Bruno might be the principal representative of the doctrine of the decentralised, infinite and infinitely populous universe (Ibid., 39).

Bruno stated that only a living universe must be able to move and change, and that motion and change were signs of perfection and not lack of it. He also suggested that infinity was inaccessible for sensual perception and unrepresentable for imagination (Ibid., 45).

René Descartes offered the first rational interpretation of the universe, away from our daily life and experience. Space became a strictly mathematical world, a world of Euclidean geometry. He believed that there was nothing else in the world but matter and motion and that matter was identical to space. He was convinced that there is nothing that can be considered a void, that ‘the void is not only physically impossible, it is essentially impossible’. He established that matter and space could only be distinguished by abstraction. He also thought that bodies are not in space but only among other bodies and that the space that they occupy is not anything different from the bodies themselves (Ibid.,101-102).

In his lectures, Alexandre Koyré suggests that Isaac Newton was a careful writer and avoided the definitions of time, space, place or motion. He carefully observed that absolute, true and mathematical time and space were opposed to the merely common-sense of time and space. He believed that absolute space is intelligible and remains always similar and immovable and that relative space is sensible and attached to the body. (Ibid.,161-162). Koyré also explains that British mathematician Joseph Raphson defined space as "the innermost extended entity (whatever it be) that it is the first by nature and the very last to be obtained by continuous division an separation". It is said that Raphson considered and reflected upon different concepts and suggested that space is infinite, space is pure act, space is all containing and all penetrating, space is nearer to us than we are to ourselves, space is the all-permeant and the all-embracing, space is incomprehensible to us, space is most perfect in its kind and things can neither be nor be conceived without it (Ibid.,193-196). In my opinion, most of these concepts present ideas that should be part of any reflection about the nature of space.

In The Birth of Tragedy, Friedrich Nietzsche argued that the rationalist perspective merely took over an illusory point of view and that one could not gaze at the world without being influenced by one’s desires. He sustained that, far from providing enlightenment about the nature of the universe, the rationalist philosopher ended up “blinding himself miserably over dusty books and typographical errors.” (Golffing 1956, 27.)

In the Phenomenology of Perception, Maurice Merleau-Ponty suggests that the perception of space and the perception of the thing, the spatiality of the thing and its being as a thing, are not two different problems. He observed that the Cartesian and the Kantian tradition taught us that spatial distribution was the only possible significance of existence and that intellectualism reduced the former to the latter. Merleau-Ponty sustains that experience discloses a primitive spatiality which merges with the body’s very being. According to his philosophy, the body is not conceived as an object of the world, but as our means of communication with it. To be a body is not primarily in space: it is of it. (Merleau-Ponty 1945, 171) "My whole body is not an assemblage of organs juxtaposed in space but my undivided possession in-the-world." (Ibid., 112-113.) "My body is the place where I appropriate space." (Ibid., 178)

It is probable that we shall never come to understand why existence is spatial. ‘’Space is not the setting (real or logical) in which things are arranged, but the means whereby the position of things becomes possible. Space is the universal power that enables things to connect.’’ (Ibid. 284).

In 1905, Albert Einstein published the definitive scientific evidence that proved that matter was conformed by atoms and space became a soup of cosmic particles that appear and disappear in constant motion. Theoretical research shows how vast the knowledge of space is. And most of the philosophers and scientists have discussed the possibility of space being impossible to measure or calculate, boundless, unbounded, limitless, interminable, imponderable, immense, inestimable or incalculable.

In The Practice of Everyday life, sociologist Michel De Certeau takes us to reflect upon space as a social and cultural practice. He writes that space (espace) is a composed intersection of mobile elements actuated by the ensemble of movements deployed in it and that place (lieu) is the order in accord with which elements are distributed in relationships of coexistence. He suggests that space occurs as ‘the effect produced by the operations that orient it, situate it, temporalize it, and make it function, in a polyvalent unity of programs or proximities’. He seems to recognize its performativity when he considers that space ‘is like the word when is spoken’, dependent upon many different conventions, situated as the act of a time and modified by successive contexts. De Certeau defines space as a practiced place (De Certeau 1984, 117).

In The Production of Space, Henry Lefebvre suggests that mathematicians appropriated space and time, invented abstract spaces and space became pure theory. No limits at all have been set on the concept of mental space. No clear account of it has ever been given. (Lefebvre 1974, 3) According to Lefebvre there are ‘descriptions and inventories of what exists in space, that may even generate a discourse on space, but they can not give rise to a knowledge of space’.

Lefebvre suggests that any scientific technique or theoretical practice designed to clarify and distinguish elements within the chaotic flux of phenomena, merely adds to the muddle. He explains that we are confronted by an indefinite multitude of spaces, each one piled upon or contained within the next: geographical, economic, demographic, sociological, ecological, political, national or global (Ibid., 7-8). Lefebvre suggests that spatial knowledge can be put together under three theoretical fields: Physical space: Nature, the Cosmos, Mental space: Logical and formal abstractions and Social space: The Logic-epistemological space occupied by sensory phenomena, including the products of imagination, such as projects, symbols and utopias.

Why should we keep treating space as a void?

How do we bridge the gap between the space of the philosophers, mathematicians and scientists and the spaces of common people?

I would like to reflect upon Merleau-Ponty’s ideas (1945, 296) and consider that space and perception saturate consciousness and are impenetrable to reflection but they represent the perpetual contribution of bodily being. A communication with the world more ancient than thought.

I would also like to consider space as a system of possible actions. I came to this conclusion after an experience I had working with space on stage, on a regular day of scenic design practice.

Performing Spatiality

As a scenographer, I am used to producing new visual material for my professional portfolio and my practice based research. The documenting process usually takes place during technical rehearsals and basically consists of making hundreds of pictures. Rehearsals are to be considered a regular condition for the staging of a play and include a pre-selected ‘audience’ that is usually conformed by the people working in the production. Rehearsals are invisible for a regular audience.

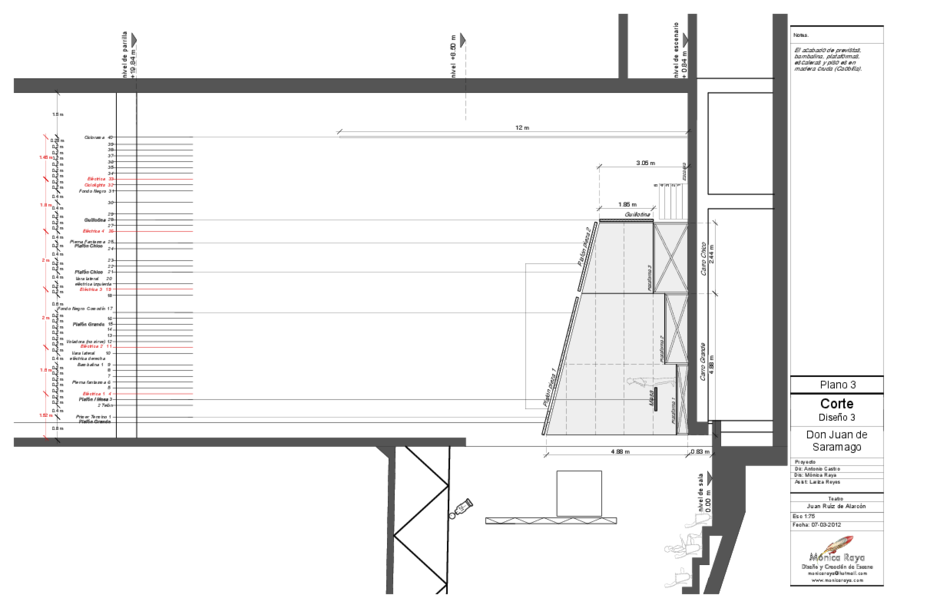

Don Giovanni or the Dissolute Acquitted, a play by Jose Saramago, was premiered at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in 2012 and I was invited to work as a scenic, costume and lighting designer. While I was in rehearsals and in the process of documenting my scenography, I witnessed an alternative spatial performance that was performing by chance and played naturally.

The first sight of the space going beyond its scenic duties was experienced when we were timing the scene changes. The scenery movements were detached from their dramatic rhythm and the task revealed an unexpected behavior. A silent choreography of appearing and disappearing shadows played in front of our eyes… I used my camera to make a video of the accident. The first video captures a new spatiality playing outside the rules. It takes 20 seconds before you can see the first change in the frame. My voice can be heard calling the technical cues and talking to the stage manager.

Don Giovanni or the dissolute acquitted

Production: Teatro UNAM

Author: José Saramago

Translation: Pilar del Río

Director: Antonio Castro

Set Designer, Lighting Designer, Costume Designer: Mónica Raya

Sound Designer: Miguel Hernández

Photographer: Andrea López

Executive producer: Mauricio Romero / Eje 7

Assistant Director: Tina French

Assistant Set Designer, Lighting Designer and Costume Designer: Lariza Reyes

Assistant Sound Designer: Enrique España y Guillermo Acevedo

Cast:

Don Giovanni: Martín Altomaro

Leporello: Carlos Cobos

Donna Elvira: Lucero Trejo

Commendatore: Humberto Solórzano

Donna Ana / Zerlina: Erika Koré

Masetto / Don Ottavio: Rodolfo Blanco

Technical Construction: Mario Alvarez, Agustín Padilla, Antonio López, Juan Benito Juárez, José Alvarez, Jonathan Mejía e Inocencio Maldonado

Costume Maker: Yesenia Olvera, Rogelio Maldonado, Francisco Piña

Fabric Painting: Eloise Kazan

Production Staff: Joel Olmos Rosas y Armando Ruiz

Special Effects: Alejandro Jara

Stagehands: Mario Alvarez, Mauricio Maldonado, Arturo Romero, Inocencio Maldonado, Vicente Camacho, Jonathan Mejía, Rúben Domínguez, Cruz Martínez , Alberto Ramírez, Iván Sánchez , Natividad Quintana, Santiago López.

Venue: Teatro Juan Ruiz de Alarcón

Teatro UNAM

Director: Enrique Singer

Theatre Department Manager : Charleen Durán

Production Department Manager : Ricardo de León

Press and Public Relations Manager: María del Carmen Rodríguez

Administration Department Manager: Alfredo Estrada

2012