Title page Introduction Theoretical Background Intervention Conclusion and Discussion Acknowledgements Appendixes Bibliography

How can performers embrace vulnerability? Brown’s research has shown that the best place to start is with defining, recognizing and understanding vulnerability. When we understand what vulnerability is and recognize how we arm ourselves against it (by numbing, perfecting, pretending etc.) we can start disarming ourselves. At their core, all strategies of disarming are about “being enough”, and, believing that we are enough. We have to believe that showing up, taking risks and letting ourselves be seen is enough. To embrace vulnerability, we should not walk away from, but appreciate our cracks, our imperfections. For it is our nature to be imperfect. Of course, embracing vulnerability is not a substitute for deliberate practice and strategic preparation. Being well prepared for performances, allows for vulnerability. This is integrated in the strategies for embracing vulnerability on stage, mentioned in the next chapter.

“When we believe that we are enough, we stop screaming and start listening.” (Brown, 2010). When we believe that we are enough, we stop trying to impress and prove, and can start making music from our heart, fully engaged and in connection with ourselves, our music and our audience.

Part 2: Embracing vulnerability

Dr. Brené Brown is an American research professor who spent her career studying the concepts of courage, vulnerability, shame, and empathy. Brown wrote seven books and her TED talks have been widely viewed. In her books and TED talks, Brown speaks about shame, vulnerability and connection.

Over a decade of research on vulnerability taught Brown that vulnerability is not weakness. To feel is to be vulnerable. To believe vulnerability is weakness, is to believe that feeling is weakness. The emotional exposure, risk and uncertainty we face are not optional, says Brown. The only choice we can make is whether we engage. Are we going to show up and let ourselves be seen, or will we sit on the sidelines, waiting to be perfect and bulletproof, before we enter the stage?

“Our willingness to own and engage with our vulnerability determines the depth of our courage and the clarity of our purpose; the level to which we protect ourselves from being vulnerable is a measure of our fear and disconnection.” (Brown, 2012)

As Brown shows in her book ‘Daring Greatly’ (2012), psychology and social psychology have produced very persuasive evidence on the importance of acknowledging vulnerabilities. From the field of health psychology studies show that perceived vulnerability, meaning the ability to acknowledge our risks and exposure, greatly increases our chances of adhering to some kind of positive health regimen. The critical issue is not about our actual level of vulnerability, but the level at which we acknowledge our vulnerabilities around a certain illness or threat. (Aiken, Gerend & Jackson, 2001) From the field of social psychology, influence-and-persuasion researchers conducted a series of studies on vulnerability. They found that the participants who thought they were not susceptible or vulnerable to deceptive advertising were, in fact, the most vulnerable. The researchers’ explanation for this phenomenon says: “Far from being an effective shield, the illusion of invulnerability undermines the very response that would have supplied genuine protection.” (Sagarin, Cialdini & Rice, 2002)

When it comes to artists, Brown says: “To create is to make something that has never existed before. There’s nothing more vulnerable than that.” When performing, musicians can’t escape vulnerability. Performing is being vulnerable, is experiencing vulnerability. “When we pretend that we can avoid vulnerability we engage in behaviors that are often inconsistent with who we want to be.” We consciously or unconsciously arm ourselves against feeling vulnerable. We numb, perfect, pretend or try to make everything that is uncertain, certain. This of course is not what musicians should be wanting on stage. Numbing might sound like a clever solution, but as Brown explains, we can not selectively numb emotion. When we numb vulnerability, we also numb fear, excitement, joy or whatever other emotion. As mentioned before, emotions are of great importance to perform with full engagement, to achieve a state of ‘flow’. The main role of music is to convey emotion and to move the audience.

Brown states that we are wired for connection, that connection is what gives purpose and meaning to our life. She also explains that we must allow ourselves to really be seen, in order for connection to happen. But we cannot let ourselves be seen and heard if we are terrified by what people might think of us, or of our playing. If we are hiding out of shame, we won’t connect. Shame resilience is key to embracing vulnerability. If we want to be connected, want to be fully engaged, we have to be vulnerable.

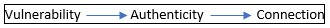

In her research Brown found that connection is a result of authenticity. (Brown, 2010). She also states that vulnerability is not only the core of shame and fear and our struggle for worthiness, but appears to also be the birthplace of joy, of creativity, belonging and love and the source of hope, empathy and authenticity. (Brown, 2012). Combining these two findings led me to the following hypothesis: