Abstract

In this essay I describe two projects within the field of visual art. Both works are examples of how the workflow techniques of digital photography can be modified in order to produce artworks that take on a distinct physicality and objecthood, and, as such, may form a spatial and/or haptic relation with the viewer. I discuss how such an approach relates to the ability of photography to point beyond the physical situation of viewing due to the particular virtuality of the photograph. By relating my work to the ideas of Vilém Flusser and Roland Barthes, recent theory on photography and photographic indexicality, as well as contemporary artistic work, I speculate here on how my own work illuminates perceptions of the photograph and understandings of the role of photography in today’s media culture and economy.

Playing against the Camera

Erik Friis Reitan

PhD fellow, Bergen Academy of Contemporary Art, University of Bergen

Chess-players too pursue new possibilities in the program of chess, new moves. Just as they play with chess-pieces, photographers play with the camera. The camera is not a tool but a plaything, and a photographer is not a worker but a player: not Homo faber, but Homo ludens. Yet photographers do not play with their playing but against it. – Vilém Flusser, Towards a Philosophy of Photography, 1983

The idea of doing things the ‘wrong’ way in order to come up with new or unexpected content is one of the things that brings our different art practices forward. Not unlike how small mutations on a cellular level cause differences in organisms which may provide them with an advantage in natural selection, artists search for ways of using their tools and performing their practice to seed new understandings of what art is and can be.

As an artist I work with photographic techniques. In my practice I often encounter image conventions and technical equipment features that are premised on expected outcomes: one type of photograph. Not unlike a musical instrument, there is a ‘right’ and a ‘wrong’ way of using the equipment. A very simple example can be seen in a camera’s focus setting, which you are supposed to use to ensure your main subject remains sharp. If you take a portrait, the convention is to focus on the closest of the sitter’s two eyes to render a ‘correct’ portrait photograph. There are now advanced digital algorithms in modern cameras and smartphones designed to help the photographer adhere to such conventions. By breaking them, however, the photographer can draw attention to features of the photographic image which are normally taken for granted. The particular ways in which the conventions are broken can also present a symbolic or metaphorical context for the image subject. One such example of this is the work ‘Ghost’ by Israeli artist Ori Gersht, produced in 2004–05. His series of analogue photographs depicts olive trees in the Palestinian villages of the war-torn region of Galilee in Israel.

When photographing the olive trees Gersht deliberately overexposed the film, allowing vast amounts of light into the camera and effectively causing the negative to ‘burn out’. In addition to the focus, a photographer also needs to get their exposure right to produce a photograph with the ‘correct’ distribution of light and dark areas. If too little light enters the camera, the image will be too dark and will not appear: analogue film at a certain level of underexposure does not contain any emulsion at all and hence is devoid of image information. This relation is not so straightforward when it comes to letting too much light into the camera. Unlike underexposure which erases the emulsion, in this case the emulsion will remain on the film due to a different chemical reaction; when the film is developed it is rendered completely dense and without detail visible to the eye. However, the physical properties of analogue film are such that even if the photographer makes a ‘mistake’ such as this, there will still be details buried deep in the negative that are possible to extract. Gersht printed his overexposed negatives in a darkroom; they required hours of exposure due to their density. But slowly the ghostly traces of the images of the olive trees were extracted, resulting in painterly images with washed-out details and distorted colours.

Violence and war are recurring themes in Gersht’s work. He has likened the process effect of allowing the burning desert sun to ‘destroy’ the negative to the acts of violence and war that have ravaged the Palestinian lands for so many decades. In his work the centuries-old olive trees become symbols for the Palestinian people, and the technical process itself takes on a metaphorical role, enveloping the subject of the images, the trees, in a poetic yet highly political frame.

The Camera ‘Program’

As Czech-born philosopher Vilém Flusser claimed, our culture is recognisable in cameras, and cameras are the result of applied scientific texts.1 The camera is a tool to produce photographs, and this makes photographs different from traditional images. The camera’s way of functioning, the photographs it produces, and society’s expectations towards these photographs are what Flusser calls the ‘program’ of the camera. Just as there is a program of chess, the program of the camera (and of photography) structures how we relate to this particular practice.

The camera is programmed to produce photographs, and every photograph is a realization of one of the possibilities contained within the program of the camera [...] Photographers endeavour to exhaust the photographic program by realizing all their possibilities. But this program is rich and there is no way of getting an overview of it. Thus photographers attempt to find the possibilities not yet discovered within it: They handle the camera, turn it this way and that, look into it and through it.2

Note that the ‘program’ of the camera is not restricted to the mechanics and digital infrastructure within and around camera technology: the photographic program shapes what we do and say in the world.

The event dines on images, and the images dine on events. The moon landing was made to produce a television program, and a mission to the moon was on the television broadcasters’ schedule. Part of getting married is to be photographed, and weddings conform to a photographic program.3

Thus, photography not only documents, but shapes the events in the world. Photography is entangled in the world, and, thus, society also lays down the conditions for what photography might be, how it is used and understood:

It is not only that ‘documentary value’ can no longer be anchored in the camera itself and its imagined access to the real, so that there can be no more talk of a continuous documentary tradition arising from the nonmanipulative use of this camera’s natural properties. It is also that, if there is a link between documentation and ‘documentary’, it comes not via the pristine camera and its transparency to good intentions but via the institutions, discourses, and systems of power that invest it and sully it, and via the discursive regimen that constitutes the document and holds it in place.4

The documentary capacity of a photograph comes not only as a result of a technology that is able to reproduce reality with seeming accuracy, its truth value depends on society investing trust in these sorts of images and constructing contexts and institutions around them to guarantee their truth. The consequence of this is that the photograph is associated with reality in a certain way, and by adhering to the conventions of photography a photographer can reap the benefits of this social investment in truth. But photography’s particular relationship to reality also provides ample possibilities for artists to explore ontological and phenomenological questions by subverting the documentary status of the photograph.

In the epigraph of this essay, Flusser describes the photographer not as a worker, but as a player. He does this because photographers are playing around inside the camera program, but unlike chess players who are limited by the rules of the game, the photographer is not limited by rules but by choices, which are nevertheless limited by the categories of the photographic program – it is a programmed freedom. At some point the photographer may go beyond what society is ready to include in the category of ‘photography’ and consequently risk losing out on society’s investment in the truth value of photographs. This is something that I take into consideration as a visual artist working with experimental photographic techniques. I’m interested in how the work of art might be interpreted through a different framework. Whether this is a ‘good’ thing is not a given, but in an artistic research context it is certainly something to be mindful of – how a work ends up being read.

Technological Development

The technology that we know today as ‘photography’ (or to use Flusser’s slightly broader term, ‘technical images’, or ‘lens-based media’ which includes cinema and video) has since its inception been intertwined with the market economy’s constant demand for innovation and novelty: it is an artistic medium whose tools are in constant technological development, constantly supplying novel ways to reproduce events, from the invention of roll film which brought photography to the masses via the development of colour photography, to today’s practice of networked sharing on social media, to name but a few. Since photography is so connected with technological, economic and social development, every new photographic technique brings new social practices and new ways of perceiving reality and relating to the truth.

The transition from analogue to digital photography is perhaps the most obvious development. The digital photograph not only challenged the perception of truth in photography (the relation between the photographed object and its image), it also changed how photographs are viewed, shared, used, and, not least, where they are. In her recent PhD project Event Horizon, Cecilia Grönberg illuminates this question:

After the integration of digital photography into online networks, the question of distribution has [...] become an integrated aspect of the digital image, its form of existence; it is no longer just a question of fast transmission. The digital photograph is distributed. With distributed photography I refer to a photography within which the meaning of the photographic image to a greater degree is determined and negotiated through a host of technological and discursive networks. More interesting than the question of ‘what is photography’ [...] is today the question of what photography does, and perhaps also, where it is.5

In addition to placing special responsibility on artists to elucidate how reality and perception is shaped by a certain ideological paradigm through the proxy of photographic technology, the intimate relationship between photographic technology, modernity, industrialisation and mass communication provides a complex set of parameters that photographic artists can use to critique power structures and social conventions, or to investigate human perception. Artist Thomas Ruff has systematically explored isolated properties of the photographic process and apparatus, including its movement into digital realms. His early analogue ‘Portrait’ series (1986–91/1998) is a clear example of how very simple tweaks in presentation may bring the objecthood of the photograph to the fore and at the same time critique the assumption that photographs are able to transmit knowledge or information. The work is basically a series of highly enlarged passport photos of friends and acquaintances. The images are devoid of additional information, save the name of the sitter in the work’s title. What sets them apart is their monumental size. Here, all the artist did was to alter the size of a familiar image form, a portrait, to cause a shift in attention towards the photographic object itself. As the artist remarks:

If you look at a portrait of a person, it can’t give you any information about the life of the sitter, like, is he going to have a visit from his mother in two hours? So what kind of information can a photograph deliver? I have no idea of what kind of information a portrait can convey. I think the possibilities of a photographic portrait are very limited. If there are photographers who say their portraits give more information than mine, I say they only pretend.6

Later Ruff proceeded to investigate the vast amounts of image material on the Internet. In another series (with its tongue-in-cheek title) ‘Nudes’ from 1999, he exposed the underlying structure of the digital image. On porn sites there are usually thumbnail images that point the user to a larger version of the image, a series of images, or a movie clip. Ruff copied these thumbnails, which consist of a very small number of pixels, onto his computer and through an elaborate process upscaled them to massive wall-size images. The results were painterly, blurred photographs, which depending on viewing position and distance both reveal and disguise the graphic content: the works not only expose the underlying technical structure of the digital image, but also show how little information a photograph actually contains and equally how much can be generated in the process of its making.

As mentioned, the camera industry (and to an increasing degree tech-industry giants like Facebook and Twitter) has a certain hegemony when it comes to expanding the photographic ‘program’, since they develop the technologies used by the masses. Granted that this development is a response to the popular use of existing technologies and services, the apparatuses and practices that make it onto the market are nevertheless largely the results of economic rather than aesthetic considerations. The tech industry’s dominance means that they are at liberty to define what is included in the vernacular concept of ‘photography’ – through their control over the means of production, so to speak.

One artist who has taken this issue on is Clement Valla, with his Postcards from Google Earth (2010–). He describes the project thus:

I collect Google Earth images. I discovered strange moments where the illusion of a seamless representation of the earth’s surface seems to break down. At first, I thought they were glitches, or errors in the algorithm, but looking closer I realized the situation was actually more interesting – these images are not glitches. They are the absolute logical result of the system. They are an edge condition – an anomaly within the system, a nonstandard, an outlier, even, but not an error. These jarring moments expose how Google Earth works, focusing our attention on the software. They reveal a new model of representation: not through indexical photographs but through automated data collection from a myriad of different sources constantly updated and endlessly combined to create a seamless illusion; Google Earth is a database disguised as a photographic representation. These uncanny images focus our attention on that process itself, and the network of algorithms, computers, storage systems, automated cameras, maps, pilots, engineers, photographers, surveyors and map-makers that generate them.7

Photographic material collected by satellites is combined with multiple sources of information on Google Earth, both official maps and user input; to a certain extent it is all put together by artificial intelligence. Not only does Valla’s work show how an artist can expose an imaging system structure, its faults and errors, it also illustrates how the photograph has merged with other image forms which claim to accurately represent reality (such as maps), and to a greater degree reveals how the photograph has detached itself from human agency.

The way that photography is performed, shared and viewed by machines is an aspect of what writer and artist Joanna Zylinska calls ‘nonhuman photography’. Interestingly, she includes other, more natural forms of mark-making, devoid of human agency, under the term ‘photography’. Referencing geologist William J. Harrison, she goes so far as to propose that photography existed even before humans produced cameras, computers and artificial intelligence: a fossil or even sunburn can be considered a photograph; the latter having been caused by the rays of the sun hitting a surface like the way film is exposed or a sensor is activated.8

Contrast this with the digital image, where visual information is translated into a series of numbers, which is then read and rendered by screen or printer. Many will contend that this process of translation breaks the direct transmission associated with analogue photography, its indexicality, in favour of a photographic form that is more virtual and detached from the depicted object. Is there a way then to make the photograph, an image increasingly delocalised and virtual, relevant on a spatial and corporeal level without relying on a return to the technological anachronisms of analogue camera technology and chemical process? Could such a departure say something useful about photography in today’s image culture?

My Practice

I am interested in exploring how a combination of digital and materialist techniques can be used to create photographic works that break away from everyday categories and vernacular understandings of photography, whilst remaining relevant as a reflection and critique of how photography shapes our perception and culture. I want to find ways of producing photographic representation which is not necessarily ‘new’, but nevertheless different from how photographs are experienced every day. I wish to do this to show what photography might be, and to initiate a sort of re-mystification of the medium that demonstrates its more sensual and tactile qualities with the hope that this may shed light on people’s habitual engagement with photography. This is because our engagement and lived relations with photography – absorbing, sharing and liking – has increasingly become controlled by an economy in which large corporations produce the tools and consequently the practices of working with photographic material.9 Since photography in part shapes our perception of reality, I believe that artists can show alternative ways of engaging with the photographic image, as well as highlight that the commodified circulation of images on the Internet is but one way in which the photograph can exist in the world. In the following I exemplify this approach by discussing two of my works. In doing so I suggest that the photographic image can take on a new form of indexicality.

Two Works

Panorama paintings were a curious example of a proto-cinematic image form, which sought to immerse the viewer in a virtual image space. The panorama painting would usually cover the walls of a circular room, sometimes it was augmented by physical props, figures and material, like sand and soil. As artist Jeff Wall comments on his photograph Restoration (1993), depicting the restoration of the Bourbaki Panorama in Switzerland:

A panorama can never really be experienced in representation, in any other medium. I made a 180-degree panorama photograph of a 360-degree picture and so had to show only half of it [...] Maybe this unrepresentability was one of its great historical flaws. That fact that panoramas emerged so strikingly, and then died out so quickly, suggests that they were an experimental response to a deeply felt need, a need for a medium that could surround the spectators and plunge them into a spectacular illusion. The panorama turned out to be entirely inadequate to the challenge. The cinema and the amusement park more or less accomplished what the panorama only indicated. [...] Lately, with virtual reality devices, we’ve come back in a way to a ‘panoramic aesthetic’, which doesn’t want to have any boundaries.10

The panorama painting became one of the many redundant curiosities of media history, and, as Wall explains, its redundancy was due to other media coming along and serving the same need in a more convincing and perhaps cheaper way. Apart from providing a superior immersive experience, the reproducibility and transportability of cinema made it more adept to the growing market economy.

Another interesting manifestation of the panorama image has a different and much longer history, namely the handscroll. The handscroll from China and Japan is a form of displaying panorama images on a long continuous strip of paper, which when rolled out to its full length contains a complete image – you were not able to see the whole image and neither were you supposed to. Instead of showing a frozen moment, the handscroll would tell a visual narrative almost like a comic strip, one section at a time. My panorama work 920° (2013) can best be described as a photographic handscroll.

The contemporary photograph is usually presented in its entirety, all at once; the full image is visible in an instant, while the gaze is free to roam across the surface of the image. Nevertheless, there are numerous strategies photographers can use to guide the viewer’s gaze, such as the structure of the composition, dodging and burning areas to make them lighter or darker, or using the focus to emphasise some elements while hiding others. In portraiture a very common convention is to set the camera’s aperture to a very open position so that only the subject photographed is sharp, while the background is left out of focus. This effect has become such a convention that it is now being simulated by smartphone cameras. I believe, however, that such selective focus is manipulative, because the photographer so explicitly and actively denotes what is important (sharp, detailed) and what is not (blurred, lacking information). Large aspects of the context are only hinted at, without providing the necessary information for the viewer to make an informed decision about the entire scene. But is this situation any different to the panorama image, where the whole scene is presented in its entirety?

In our digital age it is easy to produce a photographic panorama image – you may even have a panorama setting on your phone. The panorama is produced by moving the camera horizontally as a series of images is taken which overlap each other. A computer then finds the areas of overlap and splices the images together seamlessly to produce a full 360-degree representation of the scene. There are different viewing applications that present such image material with added interactivity, where the viewer is able to virtually ‘look around’ an image space, on Facebook or realty websites, for example.

When using larger cameras to produce panoramas, photographers use a dedicated tripod for better precision. This is what I used to produce the panorama for my handscroll 920° set in a forest. I kept all camera settings (exposure, focus, tilt, etc.) completely unchanged throughout the sequence. And then using a minimal depth of field (so that only very small areas were in focus at any one instance), I shot a series of horizontally overlapping images, while moving the focus ring of the camera ever so slightly between each image. This is not ‘allowed’ in the system of the panorama software which requires that all input images have exactly the same settings. But by moving the focus selector in minute steps between images and using a little manual tweaking I fooled the software into thinking that the images belonged together, even though the focus point moved for each image. By doing so, the left side (start of the rotation) of the resulting panorama image was sharp, leaving the rest of the forest as a green haze. As the camera rotated the focus would shift progressively towards the edge of the forest, so that by the end of the scroll (right side), the foreground was blurry and distant trees were in focus.

The result was a 12m-long photograph which had to be printed. Photographic paper comes on rolls and most papers only let you print on the outside of the roll; the rolls also rely on a tension when printing, which makes it near impossible for the image to be on the inside of the roll too. I needed to find a paper with printing surface on both sides and to customise a printer in order to accept the paper the ‘wrong’ way. Once completed, the long strip of paper could be placed between a pair of scroll handles, which I employed product designer Suzanna Mantorski to develop and produce. The work was exhibited on a table with cotton gloves that allowed the viewers to handle the work – they were informed of this possibility when entering the exhibition. I was curious to see how viewers responded to this experimental work: many said they experienced a strong urge to get to the end of the scroll, to figure out ‘what would happen’, what was hidden deep inside the paper roll.

Panorama photography dates back to nearly the invention of photography itself. Photographers quickly realised that if they wanted to capture a wide view of a city or a vista, for example, their lenses and film were not adequate enough to cover the whole scene. They therefore found ways to combine several exposures, one after the other, to achieve this. Thus, the panorama promises more information than regular photographs. Today, panorama technology carries the same motivation. Digital platforms, such as Google Maps, have embraced the photographic panorama – using Street View we are now able to pan across the world in 360 degrees. As with panorama paintings, you get the impression of being served the whole scene at once, and it is you who chooses the point of view. It is a kind of virtual reality. Furthermore, the panorama image promises a ‘democratisation’ of the image: everything in the scene is there, all the information is available; you the viewer, not the photographer, gets to decide what is important and what is not.

In my scroll work I attempted to subvert this perception in two ways. Firstly, by the constrained scroll format, which only lets you see about 70cm of the scene at any one time. Secondly, this viewing effect is doubled by the extremely selective focus of the image, which reveals very specific parts of the scene while hiding others in a haze of green bokeh. Now, this concealing of certain image areas also applies to a digital panorama or a virtual reality experience, where you rotate inside the image space to see the rest of the image and thus always have your back to one part of the image; even when viewing regular pictures your eyes select certain parts of an image to see at any given point in time. My intention here was to amplify this experience and place it on a corporeal level by having the viewer struggle with the somewhat cumbersome and heavy handscroll when taking in the scene.

My approach was to consider how photographs are perceived more generally today, especially as the photograph has spread across the world on such a vast scale. On the one hand, the distribution of images implies that the viewer gets to see everything, because so much visual material is available, on social media, on TV, in magazines, everywhere. On the other, the constant availability of different viewpoints makes it all the more apparent that we only ever get to see a certain part of the truth. Additionally, this access to visual information happens through very specific visual programs and conventions that structure how the world is presented to us and how we interact with it. We should therefore ask about how information is socially distributed. The ability to decipher the visual codes that colours the information we are given is not equally distributed: we may be more easily manipulated or reduced to a very dull existence controlled by the requests of cameras, machines and the algorithms of social media and Internet advertising which serve content they expect us to like or agree with. This becomes all the more important as we have entered an era where the idea of objective truth and fact is under increasing threat.

This apparently non-symbolic, objective character of technical images leads whoever looks at them to see them not as images but as windows. Observers thus do not believe them as they do their own eyes. Consequently they do not criticize them as images, but as ways of looking at the world (to the extent that they criticize them at all). Their criticism is not an analysis of their production but an analysis of the world.

This lack of criticism of technical images is potentially dangerous at a time when technical images are in the process of displacing texts – dangerous for the reason that the ‘objectivity’ of technical images is an illusion.11

The scroll format and the haptic interaction between viewer and work provided an opportunity to question the role that the body plays in the experience of virtuality – the body was to some degree lost when cinema became the dominant immersive image medium and the panorama painting was made redundant. The almost scenographic way that panorama painting makes the image come ‘alive’ and be in direct dialogue with the viewer had some aesthetic qualities that I want to revitalise. Artistic research is a discipline that allows such performative investigations into media history, and in my PhD project Teleportation to be completed in spring 2021 I propose a scenario for what could have happened if the panorama painting had continued to develop. What can the sort of blending of image space and physical space that panorama paintings attempted to create look like today?

Teleportation problematises the relationship between physicality and virtuality in the perception of photographic imagery and asks if and how photography can act as a tool for distant seeing. In this project I am using photographic surfaces as raw material for building elaborate installations in gallery spaces.12 The word ‘teleportation’ describes a fantasy technology or form of magic where matter and organisms are dissolved and transmitted in order to appear somewhere else in an instant. My use of this term functions as a research tool for generating artworks, which in turn may shed light on how photography relates to spatial perception.

Firstly, photographs appear to transport ‘reality’ or ‘experience’ from one location to another by how the process of photography is structured: recording something at one location and then recreating it somewhere else. Secondly, when viewing photographs the consciousness of the viewer is in a sense separated from their physical body and transported back to where the photograph was taken. Using teleportation as a conceptual tool is also a strategy for investigating how the photograph is entangled in fantastic, sometimes utopian, promises of technological development and market economy, and how this increasingly stands in opposition to a sustainable ecology. Capitalist economy and the technological development associated with it has not been able to contain itself within sustainable ecological boundaries. The photographic image itself also represents a form of detached seeing, where optical perception is disconnected from its embodied context – our biological body. Although, certainly, we have always been able to gaze faraway into the night sky which we will never physically reach, today’s visual culture nevertheless causes me to ask: How does the increasing proliferation of detached seeing through everyday lens-based communication change the way we relate to each other and to nature, including ourselves as bodies?

The photograph plays on our sense of sight, accessing areas of reality that are not sensed by the rest of the body. Photographs extend this separation between vision and body, in that the close connection to reality inferred by the photograph can allow the image to point to objects that are no longer present, but which are still ‘accessible’ through visual representation. By introducing an element of sculpture to my work I seek to bring this mechanism into relief.

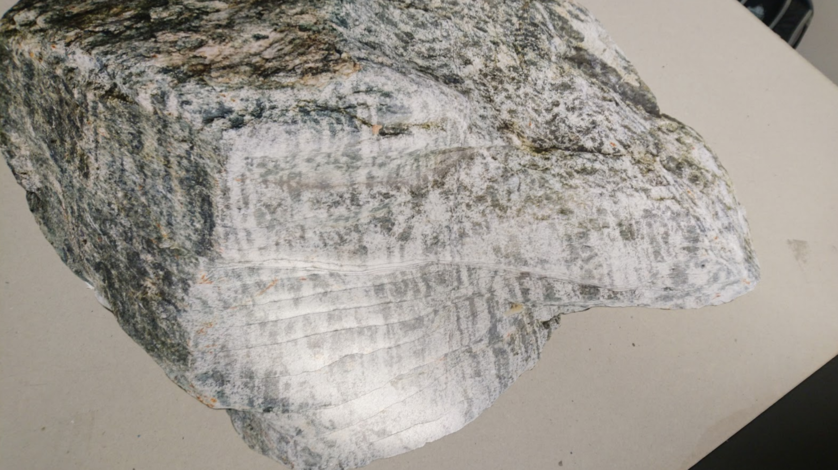

The primary subject of the Teleportation project is a vast lava field. It was created in 2014 from a fissure eruption, leaving 85km2 of new earth crust on a large sand plain. I was motivated to work in this place as I was curious about whether it would be possible to locate a ‘neutral’ raw material in the age of the Anthropocene: a slice of Earth that was ‘untouched’ and ‘unmapped’. Such a subject, which suddenly appeared after laying hidden deep within the earth for millions of years, was seemingly something yet to be affected by human influence (or natural geological processes of erosion and compression for that matter). Fragments of this lava field were photographed and the photographs were put through an elaborate process of printing, mounting and exhibition presentation, which was built up to emphasise the separation between the photographic object and the world.

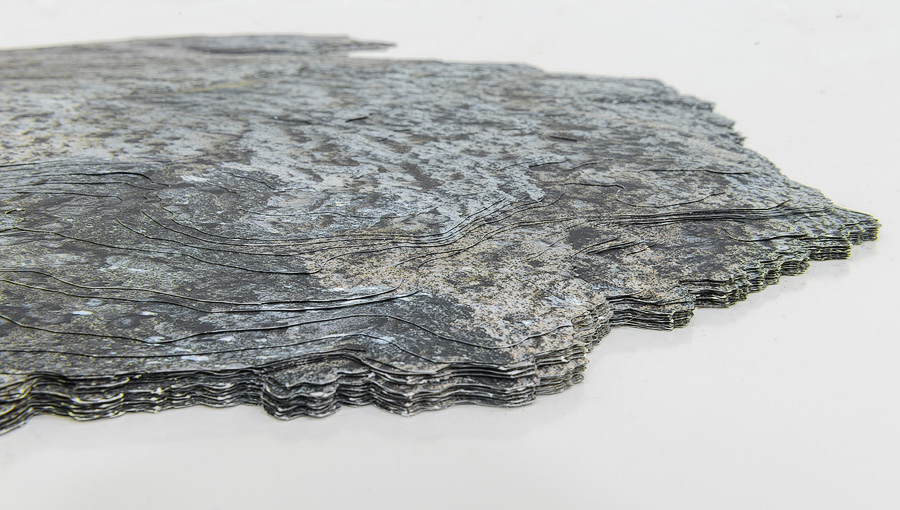

The photo-objects were made by photographing fragments of the lava field at the zenith. It required using a technique meant for other purposes, namely focus bracketing or focus stacking, which is common in microscopic imaging to produce perfect depth sharpness across the entire image. As mentioned, sharpness can be unevenly distributed due to optical limitations in the lens of the camera: there is just one distance from the camera where the image can be perfectly sharp, everything behind and in front of this point gradually becomes more and more blurry with distance. How far sharpness extends is to some degree possible to control by the aperture setting of the camera, but this has its limits too. The focus stacking technique is designed to overcome these limitations.

When you perform focus stacking you keep the camera still with a tripod and shoot a series of images of the exact same subject using a camera programme that systematically shifts the focus point very slightly for each new image.13 You then input these images onto a computer which identifies the areas in each image with full sharpness and combines just these areas as layers to form one perfectly focused image. Since the focus is actually different in each component image, each layer of the resulting ‘stack’ would respectably cover a unique area of the object. And since the focus is a distance setting, the computer software can use this information to produce a three-dimensional ‘depth map’ of the object. When producing a hi-definition digital image, the layers in the stack shouldn’t be visible, rather they are supposed to blend seamlessly so to create a perfectly focused image file which supersedes the optical capacity of the lens.

In the Teleportation project each layer in the stack was output separately, printed at a 1:1 scale on soft matt photographic paper, and then the focused area of each layer was manually cut out from the paper with a scalpel. These paper shapes were then glued on top of each other to form a physical stack, in effect creating what resembles contour lines on a map or an architectonic landscape model. This created subtle elevations and depressions in the image surface that corresponded exactly to the actual depressions and elevations of the rock. Finally, the complete stack was trimmed along the natural contour of the lava rock represented as a whole. The result was a strange image form, hovering somewhere between a two-dimensional image and a three-dimensional object – some may call it collage, others relief, and others sculpture.

As this procedure is not what the software expects the user to perform, I had to develop a customised digital workflow of selecting, copying and exporting image material to achieve the photo-object outcome. I also had to invest large amounts of time manually cutting the layers and gluing them together, even employing assistants to help me. I found it interesting to combine this very slow, labour intensive handcraft with a digital workflow, especially at a time when the technological innovation behind this technique is geared towards automation and efficiency.

For my most recent exhibition, I built a very elaborate installation around the objects. Upon entering the exhibition, the space was darkened. You would first encounter a towering, monolithic structure, seemingly made of concrete (plaster covered in fake cement) with light emanating from behind. The natural course of action would be to move towards the light. As you came around the back of the structure a narrow opening appeared, leading into a white hexagonal chamber bathed in an intense but soft light. Many viewers said that the experience was like moving through a sacred space, similar to a cathedral or temple. The inner space was meticulously built; the choice of materials was inspired by white cube art spaces, laboratories and science fiction. The installation formed a scenographic experience of detachment from the ordinary world as well as an environment to encounter the photographic objects.

The objects were laid flat on the floor, recreating the point of view of the work’s production. There were no frames, no titles and no exhibition text to explain the technique, scale or process. I intended to create a maximum contrast between the raw natural subject (the rocks), the handcrafted photo-objects and the almost clinical, white spatial context: For example, I lay a custom epoxy floor that created a shiny high-gloss surface for the objects to rest on; epoxy has a particularly hard yet slippery feel when you walk on it wearing socks (viewers were requested to remove their shoes before entering the exhibition). It is also the type of floor used in hospitals and industrial spaces due to its rock hard, non-porous nature. Such a material underscored both the utopian framework of photographic technology and the virtual nature of the photographic experience. The viewer was therefore invited to engage with the work in a spatial and tactile way. I wanted to create a theatrical situation where the viewer was torn away from their everyday experience and cast into a liminal space between illusion and lived reality. And I wanted this situation to be informed by a decidedly sensual, corporeal experience, so that movement, touch, smell and the potential presence of others in the space were as central to the aesthetic experience as the photographic artworks presented.14

Indexicality, Objecthood and Transcendence

Indexicality is one of the most debated aspects of photography. To put it short: the term describes the physical relationship between the object photographed and the resulting image.15 ‘Indexicality’ was first used in Charles Peirce’s theory of signs, which describes the relationship between a sign (such as a photograph) and its referent (the subject), in that the referent is the cause of the sign. There is a physical relationship between the two. A photograph is indexical, because it is caused by light rays being reflected off an object and registered by the camera. Peirce writes that the photograph thereby points to an object beyond itself and claims that it was there to be photographed.16

There is also an interesting link between the idea of the photograph as an imprint and that of geology – some argue that photography is an intrinsic part of the geological evolution of the earth and that this form of indexicality is but one of several ways in which photographic representation is linked to the physical world. Consider, for example, how fossils are inscribed and fixed, or how different time periods are recorded as traces in the strata of rocks and mountains. Photography is not just a technology, its way of creating traces and markings is a fundamental feature of how the world works.17

Due to its claim to indexicality, photography enjoys a particular status as evidence. And although digital photography has brought about a host of possibilities for interfering with this evidential connection, in everyday society photography and video is generally accepted as carrying a trace of what it depicts. This is however dependent upon a culture that invests in the truth of photographic representation, that we are able to identify it as a document.18 Although photographs are considered to have an objective indexicality due to the technical process that brings them about, it seems that a certain context is required for a viewer to recognise indexicality. How do you know that you are looking at an actual trace of something physical and not just a digital rendering? Is it the lifelikeness (iconicity) of the photograph that inform us of this connection, or do photographs also depend on accompanying information that ‘instructs’ us to read them as indexical image forms?

One could say that my installation was an experiment at removing as much context from the material as possible, while at the same time retaining a high degree of lifelikeness in the photographic objects presented, a lifelikeness stemming in part from the process of carefully carving out, layer by layer, the strata of the photographic object so as to heighten the depth illusion of the photograph. The work as a proposition asked: Would the photograph still be able to hold on to its indexicality, its connection to the outside world, without any contextual clues? Would it still function as ‘teleportation’? Interestingly, many of the viewers of the installation had trouble identifying the works as photographic. This is curious given my premise of exaggerating the photographic quality of iconicity and striving towards maximum lifelikeness. Some were even surprised to hear that they were viewing photographic material: they thought that the work was drawing, graphic prints, or natural material. Still, others did see the work as photographs, but not photographs of rocks as such, rather they saw them as aerial photographs of landscapes or records of something amorphous like moss, even though every object represented a rock in actual size. It appears then that lifelikeness in a photograph does not guarantee recognition or even acknowledged indexicality, even though it is objectively present – I know, because I was there to photograph the rocks. The recognition of indexicality is therefore contextual and informed by the knowledge that one is in the presence of a photographic image.

If we stick to the traditional definition of photographic indexicality, that the image is connected to the subject, the image is seen as a trace. This definition of indexicality is deeply embedded in our understanding of photographs; in fact, Peirce used the medium of photography to exemplify how indexicality works.19 There is however another way of viewing indexicality. This form of indexicality is relevant to painting, and according to critic Isabelle Graw it is in a sense the opposite of the traditional way of seeing the imprint of the object.

Whereas Peirce places emphasis on factual, physical connectedness of the index to its object, I highlight the index’s faculty for evoking or suggesting such a physical connection. Painting suggests such a physical connection to the one who made it. [...] Whereas photography, as Roland Barthes puts it, is characterised by its exceptional capacity for denoting reality; painting, by contrast, tends to bring its author into effect.20

This indexicality also has a physical connection, but relates to something else, to the author.21 But what happens when this understanding of the term is applied to photographic works? It appears that in the Teleportation project the works could also be defined by such an indexicality. Interestingly, my traces as the artist are the result of physically carving out the layers that comprise the object and its perimeter. They were determined by the information extracted from the object photographed (the volume of the rock), which was translated into digital information (the lines showing where to cut the paper). My agency was therefore severely restricted, but the traces of my labour (and that of my assistants Laura Gaiger, Dale Rothenberg and Aurora Solberg) remain. Thus, marks are left, an author is suggested, but due to the computer-generated nature of these marks, the indexicality is a more automated, ‘photographic’ way of connecting the work to the author.22 However, if these highly photographic artworks rely on a different form of connection to the world than the usual photograph, are they still to be considered photography? Are they still part of the photographic ‘program’ and thus able to tell us something about the kind of photography that we encounter in our everyday lives? If so, what can they tell us?

One answer could be to investigate what is normally identified as a ‘photograph’ and what a casual observer expects from it. Roland Barthes writes:

What is the content of the photographic message? What does the photograph transmit? By definition, the scene itself, the literal reality [...] Certainly the image is not the reality but at least it is its perfect analogon and it is exactly this analogical perfection which, to common sense, defines the photograph.23

He elaborates in Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography:

A specific photograph, in effect, is never distinguished from its referent (from what it represents), or at least it is not immediately or generally distinguished from its referent (as is the case for every other image, encumbered – from the start, and because of its status – by the way in which the object is simulated): it is not impossible to perceive the photographic signifier (certain professionals do so), but it requires a secondary action of knowledge or of reflection.24

In short, Barthes argues that the essence of the photographic experience is a twofold process: We initially experience the thing depicted as literal, it is perceived as being directly transmitted into our field of consciousness (‘this is a pipe’). The photograph itself remains ‘invisible’, a ‘transparent envelope’ (as Barthes describes). It is by a secondary act of reflection that we become aware of the photograph itself and the coding of it – how its subject has been intentionally framed, timed, manipulated, put into context and so on. When looking at Gersht’s work, for example, this secondary reflection is applied to a photographic process. By making a ‘mistake’, creating an error, when overexposing his images, he not only brings attention to the process behind a photographic image, he simultaneously infuses his errors with symbolic content. The errors reveal and arrest the transparency of the photograph, exposing the transparent envelope. Gersht’s images take on a distinct objecthood: the abstract quality resulting from his particular process brings attention to the physical picture and places them in a liminal space between painting and photography.

The intention with the photo-objects in both my projects was similar to Gersht’s approach, but it may in fact come closer to Ruff’s portrait series, where the photographic lifelikeness is overexaggerated. This is particularly the case in the Teleportation project, where I wanted the process of making and the objecthood of the photographs to retain a sense of the transparent envelope. Instead of creating disturbances in the seamless transparency of the photograph, like in the work of Gersht and Valla, I wanted to see how far I could push the lifelikeness of photographic objects, and in doing so allow the process of making and the objecthood of the work to gradually become apparent in the viewing experience. This created a paradox: the work is not only made with commercial high-definition imaging equipment,25 rendering a very high degree of lifelikeness, they even take on the outline and (to some degree) the volume of the object depicted – the work is almost hyper-photographic. Despite this, many viewers failed to identify the works as photographs. It appears that by taking their photographic lifelikeness literally, the photographs lose transparency. Stripped of their identifying characteristics, the works demonstrate that even the most photographic of photographs still depend on social context and on a familiarity with previously defined instances of photography in order to be accepted and read as photographs. This dissolution of the ‘photographicness’ of the works may be necessary however, when approaching and problematising the notion of photography as teleportation.

As mentioned, the photograph can be understood as teleportation by how it manifests something in a different location and points beyond itself to something it is not: it transports consciousness away from the physical situation of viewing. In this sense, it has a transcendental quality. It causes a split in the viewer, who ‘leaves’ their physical body behind and transports their consciousness towards the object photographed. But what happens when the works are denied their property of pointing beyond themselves, by taking on the objecthood and indexicality that I just described, and remain instead within the phenomenal field shared by vision and body? By creating a specific context that is devoid of information about the image material and then investing the works with physical qualities that render them opaque, I see a possibility for turning the ordinary photographic mechanism of representation on its head: the works point to their own being as objects in a situation shared with the viewer. The presentation of the image places the viewer in a spatial situation rather than inducing transcendence. Now a space opens for considering the fundamental principles for how photographs, whether digital, analogue, physical or virtual, are viewed by a body, a lived reality and a biological organism.

It is possible to see that there are contextual preconditions that cause the acceptance of the illusion of photographic transparency and transcendence; in this case by precisely removing these conditions. By making the scenography of the installation into a kind of science-fiction fantasy space I underscored how so much of our contemporary reality is shaped by the photographic image, how it is capable of creating fiction out of reality. Art and artistic research are practices that directly and by means of example engage with the knowledge gained from lived, sensory experience, and they carry a potential for problematising where people place their attention – in the ‘there’ of the transparent photograph, or the ‘here’ of the living body. My work can therefore be seen as an experiment in creating a singular photographic work which purposefully opposes the distributed image of the current media economy, so to investigate whether it can be accepted as photography and whether it can stimulate reflection about the current status of the medium in the vernacular. The question remains whether shifting the indexicality of the work in this way exhausts another possibility within the photographic program described by Flusser, or if it will cause my works to escape the category of photographic representation altogether.

Erik Friis Reitan (b. 1979) is a visual artist and PhD research fellow at Bergen Academy of Contemporary Art. He holds an MA from Trondheim Academy of Fine Art and a BA in photography from Kent Institute of Art and Design, UK.

Reitan’s work uses material based on or informed by photography to create spatial situations. Through artistic strategies inspired by minimalism and land art, his PhD project Teleportation investigates how photography acts as a tool for distant seeing, and how this aspect of the medium may be subverted. Photographic surfaces based on images of volcanic rocks are used as raw material to produce elaborate installations which explore how digital photography can take on distinct physical forms and engage the viewer on corporeal and haptic levels.

http://www.erikfriisreitan.com/

https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/590434/590435

Keywords

Digital, handscroll, indexicality, installation, Internet, media culture, object, panorama, phenomenology, photography, Erik Friis Reitan, sculpture, semiotics, teleportation, workflow

References

Vilém Flusser, Towards a Philosophy of Photography (1983; repr., London: Reaktion Books, 2006)

Vilém Flusser, Into the Universe of Technical Images, trans. Nancy Ann Roth (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011)

John Tagg, The Disciplinary Frame: Photographic Truths and the Capture of Meaning (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009)

Cecilia Grönberg, Händelseshorisont (Event Horizon), PhD dissertation in Design Photography, Valand Academy, University of Gothenburg, 2016

Brooklyn Rail, June 2005, https://brooklynrail.org/2005/06/art/thomas-ruff (last accessed 25 August 2020)

Joanna Zylinska, Nonhuman Photography (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017)

Isabelle Graw, The Economy of Painting: Notes on the Vitality of a Success-Medium,lecture, YouTube, 20 July 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1JDthDEcmAs&t=0s (last accessed 25 August 2020)

Jeff Wall, Jeff Wall, 2nd. ed.(London: Phaidon, 2002)

Tom Gunning, What’s the Point of an Index? or, Faking Photographs, Plenary session II, Digital Aesthetics, Nordicom Review 24, no. 1–2 (March 2103)

Charles Peirce, What Is a Sign?’ in The Essential Peirce: Selected Philosophical Writings, Vol. 2, 1893–1913 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998)

Roland Barthes, The Photographic Message, in A Barthes Reader, ed. Susan Sontag (New York:Hill and Wang, 1983)

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1982)

The Bourbaki Panorama (1881) by Edouard Castres, depicting the Franco-Prussian War

Image courtesy of the Borbaki Panorama Museum

Detail from the Bourbaki Panorama. The transition between the painting and the props on the floor can be seen where the firewood is lying, and where the first part of the fence to the right ends.

Image courtesy of the Bourbaki Panorama Museum

Isabelle Graw giving the lecture The economy of Painting - Notes on the vitality of a success medium