Re-appropriation: On Morton Feldman’s The King of Denmark

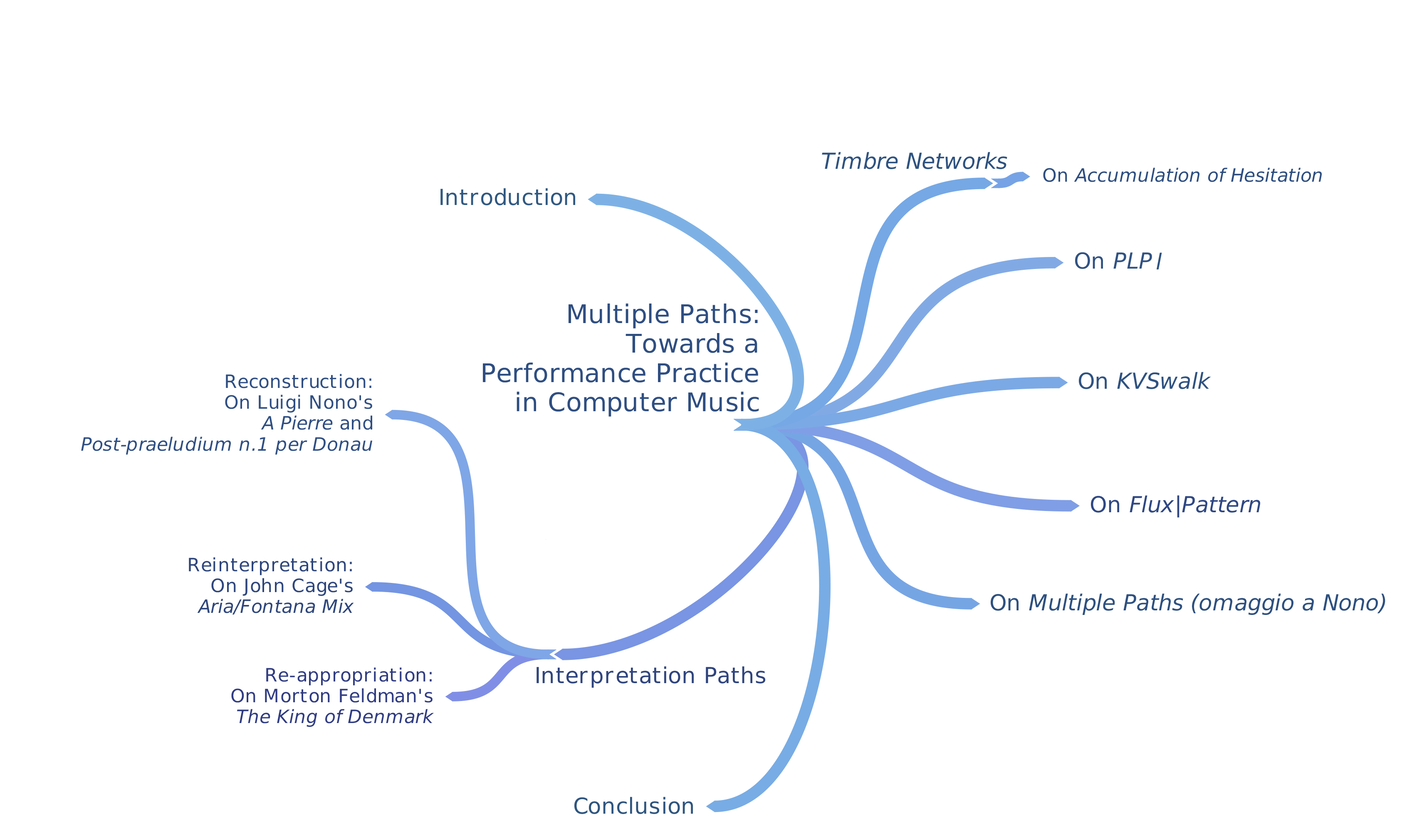

Introduction

One of the greatest challenges in computer music practice today is the lack of a performance tradition for almost all its repertoire. The sole fact that we still define computer music and live electronic music by the media that are being used rather than by its aesthetic, historic or social relevance, shows a lack of maturity in these areas. Since we are approaching nearly the ninth decade in the production of electronic music, it seems odd that very few attempts have been made to define the positive aspects of developing a performance methodology around this practice. Additionally, little has been done with regard to experimenting with the collision between what it is possible to derive from traditional instrumental practices and what escapes the norm of a traditional instrumental discipline.

A personal method for exploring and challenging these potential points of connection (and collision), has been the definition of a historical and aesthetic context through the interpretation of music that, although not conceived to be performed live by electronic instruments, is suitable for it, given the relationship between its conceptual framework and its manifestation in sound. This is what I call interpretation as re-appropriation.

Looking for repertoire to be interpreted in this way, one of the main elements that I search for is feasibility. This requires an analysis of the musical challenges present in the score, as well as an evaluation of the features and constraints demanded from a specific traditional instrument, and how these could be translated into electronic media. The other important element when selecting potential repertoire is the mapping that the composer proposes between the musical identity of the composition and the performative challenge.

This demands a specific way of interpretation. It is here that the element of “appropriation” takes place in interpretation. Once the challenges proposed to the traditional instrumentalist in the score are identified, it is necessary to seek a possible answer to the question of why the composer is posing this challenge, and from there restate the challenge, the question and a possible answer in relation to electronic media.

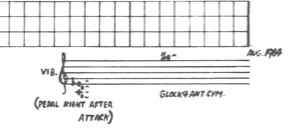

The score consists of a grid of densities, timbres and registers, and although it has a set tempo, in the words of the American percussionist Steven Schick, “no rhythmic coherence emerges. Sounds simply float out, detached and weightless. One instrument has no more sonic gravity than another does. A small bell weighs the same – takes up the same acoustical space – as a large gong.” (Schick 1998: n.p.)

In “American Sublime”, the music critic Alex Ross reviews the genesis of and reasons behind the title of Feldman’s composition:

There is no mistaking the lonely, lamenting tone that runs through Feldman’s music. From time to time, the composer hinted that the horrors of the twentieth century, and in particular the Holocaust, had made other, more ornate kinds of musical expression impossible for him. He explained that the title “The King of Denmark,” which he bestowed on a graphic piece for percussion, was inspired by King Christian X, who was occupying the Danish throne when the Germans invaded his country in 1940. Feldman proceeded to tell the story, now considered apocryphal, of King Christian responding to German anti-Semitism by walking the streets with a yellow star pinned to his chest. It was a “silent protest,” Feldman said. In a way, his music seemed to protest all of European civilization, which, in one way or another, had been complicit in Hitler’s crimes.

Whether the original story is true (it has now been documented that the yellow Star of David badge was not introduced in Denmark during the Nazi occupation), Feldman’s political view is apparent due to his focusing on this pacific protest, this silent resistance, as well as its human fragility. Feldman translates this silent resistance into performance by removing from the hands of the percussionist what had until then been his or her most important means of sound production – sticks and mallets – and instead has the percussionist produce the sounds with his or her fingers, hands or arms. The sounds produced by the percussionist’s actions now become not only soft but also fragile, played with the dramatic intention of producing sounds, or rather, performing actions that lead to sounds, at the limit of audibility – something later explored, for example, in Luigi Nono’s works with live electronics.

Flutist Eberhard Blum (Blum 2008: 1) recounts that Feldman’s silent resistance not only corresponded to a very clear political statement in music, it also served as a direct answer to Stockhausen’s Zyklus, composed five years earlier, which featured the expressivity of the solo percussionist in a completely different way:

In 1956, John Cage had composed the first work ever of this kind, his “27 ́10.554 ́ ́ for a Percussionist.” Stockhausen reacted to this pioneering work with his “Zyklus,” The soloist places a great number of instruments in a circle enclosing him, according to a plan by Stockhausen. During the performance, the player slowly turns, clockwise or anticlockwise, as he chooses, and executes one of the possible cycles of the composition. It is a most impressive and virtuoso act, one could almost say “expressionistic”.Feldman knew this work, as it was performed in New York by the percussionist Max Neuhaus shortly after its completion. He called his own new percussion work “the American answer to ‘Zyklus.’”

In contrast to Stockhausen, Feldman’s approach to the politics of the soloist led him to propose a performance where the fragility of the sounding results would suggest an equal fragility in the actions of the performer him- or herself.

It was this notion of performative fragility that I wanted to preserve when translating The King of Denmark into the electronic domain. The lack of a clear interdependency between physical action and sonic manifestation in electronic instruments led me to rethink how to expose this fragility.

Context

In particular, solo percussion pieces lend themselves to in-depth exploration, as they tend to focus on using and combining diverse sound sources, thereby generating a rich timbral texture. This is something that is not only feasible for a live computer system but allows one of the unique qualities of electronic media to shine. On the other hand, the interpretative challenges presented to a percussionist can serve as an interesting point of departure for the computer performer, as the rather clean one-to-one relationship between physical action and sonic manifestation can be emulated, contrasted and commented on by a computer music practitioner. Finally, the solo percussion repertoire has a history that in many ways parallels the history of computer music in its ongoing evolution from effect – or novelty – towards maturity.

An example of such a solo percussion piece that lends itself to being re-appropriated by electronic instruments is Morton Feldman’s The King of Denmark (1964).

Excerpt: The King of Denmark by Morton Feldman. Max Neuhaus (percussion). From the album "Max Neuhaus - Electronics & Percussion". Columbia, MS 7139.

This controller allowed me to create a variable mapping calculation whereby the input sensitivity for the instrument could vary continuously on the basis of how many pads were hit simultaneously. In doing so, the instrument would change its responsiveness (the time difference between hitting a trigger and hearing a sound), creating a visual gap between action and sound that varied throughout the performance. I decided to preserve the original ending of the piece (a sustained G# on a vibraphone) – given that it is the only traditionally notated element – by simply triggering a sample.

Project

The King of Denmark presents its performer with the challenge of balancing controlled and decontrolled elements. Feldman divided the musical parameters at the disposal of the percussionist in these two categories, providing instructions to the interpretation of dynamics and articulation (always with the same extreme softness, on the verge of not producing a sound), tempo register and duration. Rhythm and pitch are left unspecified. Pitch becomes then a quality absorbed by the timbre of the instruments chosen by the interpreter for his or her setup.

Rhythm is somewhat framed by the prescriptions of the other parameters, in as much as the natural resonances of the instruments – their constantly soft dynamics and the way they overlap – suggest the need for a sustained, stable unfolding of the piece.

My solo computer version of The King of Denmark aims to transfer the notion of silent resistance into the world of computer music by creating an interface between performer and instrument that varies in responsiveness according to the instrumental densities defined in Feldman’s score. In this way, the timbral palette remains consistent, as in the original, but the uniqueness of electronic media reveals itself through the emphasis on its disjointed nature, such as in the relationship between physical action and sonic manifestation and in the potential negation of the spatial cause/effect relationship between sonic impulses and resonances.

This approach allowed me to preserve the original challenges posed to the interpreters by the piece, while recovering the feeling of uncertainty towards the sonic manifestation of each sound. Whereas in the percussion a restrained physical effort might deem a particular action too “soft” to be heard, in the case of my version, the intensity and densities of gestures might deem a sound too “early” or too “late”.

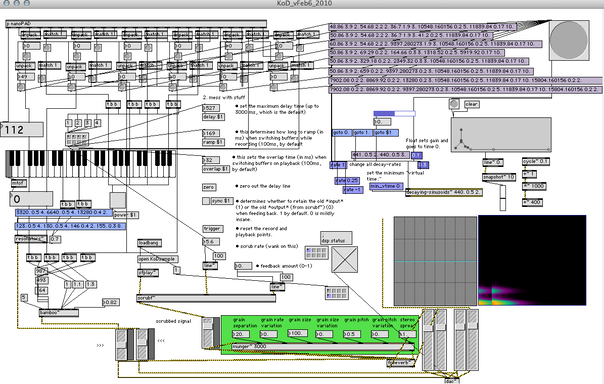

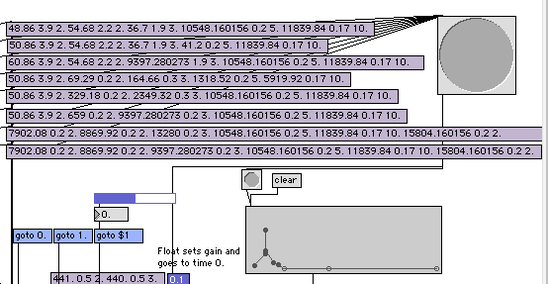

The software component of the instrument is developed in the Max/MSP environment and consists of two parts: an instance of “bamboo~”, a physical model of a wooden percussion instrument developed by computer music researcher Perry Cook as part of the PhISEM (Physically Informed Stochastic Event Modelling) Library for Csound, and a resonator bank composed of an array of twelve decaying sinusoids.

To recreate the uncertainty in audibility present in the original percussion piece, I decided to implement three elements that would help simulate a feeling of instability in the instrument. First, at each hit, the resonator bank would retune itself by rotating through a list of twelve preset pitch values.

Second, the wooden physical model (bamboo~) was used to feed a granular synthesis engine that in turn was mapped to project the sound at random intervals between four sound outputs, two of which were not connected to any speaker.

The aim of the third element of instability was to transfer the dynamic uncertainty of the original piece into the time domain; this was achieved by creating a non-linear mapping between the software instrument and the physical controller used to trigger it. This controller was a small pad array (Korg NanoPad) that, rather than sending an on/off signal, sent continuous control MIDI values according to how hard the pads were hit.

Max/MSP patch for my version of The King of Denmark. Full view, detail of the resonator bank and short demo.

Korg NanoPAD. For more information visit http://www.korg.com/us/products/controllers/nanopad2/.

Reflection

This case study aimed to capture a particular element of a piece written for a non-electronic instrument and re-appropriate it through electronic media by translating the element in question (dynamic fragility) into time displacement between physical action and sonic manifestation, in order to better illustrate the features of electronic instruments.

By focusing on the fragility of the audibility of The King of Denmark and shifting that fragility from dynamic to time displacement (or responsiveness), the piece maintained its nature while presenting a new challenge to its performer. In doing so, it was possible to emphasise a feature in electronic instruments (the nonlinearity between physical action and sonic manifestation), and present it as a tool for expressiveness and performative theatricality.

Performance of computer version of The King of Denmark by Juan Parra Cancino. Orpheus Institute, Ghent. 28 March 2010.

References

Blum, Eberhard (2008). “Notes on Morton Feldman’s ‘The King of Denmark’” (trans. Peter Söderberg). Retrieved 4 November 2014, from

http://www.cnvill.net/mfblumking_eng.pdf

Ross, Alex (2006). “American Sublime: Morton Feldman’s Mysterious Musical Landscapes.” The New Yorker, 19 June. Retrieved on 2 November 2014, from

http://newyorker.com/archive/2006/06/19/060619crat_atlarge

Schick, Steven (1998). Programme note on The King of Denmark. Retrieved 4 November 2014, from http://www.cnvill.net/mfschick.htm