The term ‘proto-object’ suggests a possible solution to the problem of the representational status of the figural. How may the outline or limit of a figure be conceptualised so as not to contradict its inner, figural workings?

Implied in this question is the assumption that, today, a conceptualisation of a figure as a ‘work of art’ overdetermines the figure because as a work of art it always has to represent not only itself but also art as a whole. In other words, today, a work of art is first an institution and not, as it may have been, an object of imagination, or, at least, a form of provisional object allowed to emerge and vanish without consequence.

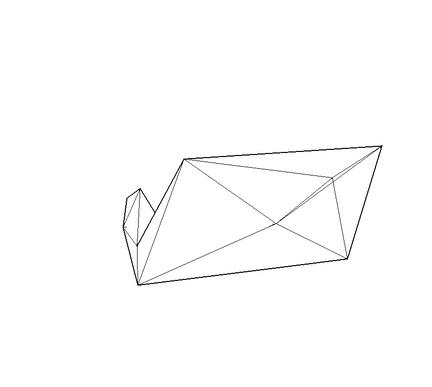

The first proto-objects were made as part of the research project Wissen im Selbstversuch / Knowledge through Self-Experimentation at the Bern University of Art (2009–10). These consist of a set of one hundred three-dimensional objects (some cast in resin, others remain virtual models), each representing a statistical snapshot of my brain activity when looking at a work from the history of art.

In terms of art, those conceptual pieces – each of which display a very particular, complex spatial organisation – have a strange status: not refined enough to already be art and not suggestive of a gesture that may turn them into a work without overdoing it. (See my Brain, 2010, as example.) The notion of ‘proto-object’ aims to take this precise status seriously as an artistic form before and below the concept of work. In this sense, ‘work’ may be conceived as a possible future or hypothetical solidification, encrustation, or decay of a potentiality that is given but not (yet) realised.

Regarding possible artistic epistemologies, proto-objects may have an important role to play since they sit right at the border at which one can start speaking of ‘knowledge’. Proto-objects are, thus, ‘epistemic things’ (Rheinberger 1997) – that is, material yet unknown realities calling for understanding. However, while in Hans-Jörg Rheinberger’s ‘experimental systems’ epistemic things can only transform into objects of science and take representational form (‘technical objects’), the notion of ‘proto-object’ suggests possible a-representational transformations; that is, they are highly-formed types of objects that resist, delay, or play with representation (both in terms of science and art). Because of this, proto-objects can also be understood as different from ‘quasi-objects’ (Bruno Latour [1993] following Michel Serres [1982]), since quasi-objects – despite sharing with proto-objects a hybrid status – are always ready to turn into proper objects as part of their prolificacy.

The trajectory of formation that is expressed in the term ‘proto-object’ sits perpendicular to the standard Kantian line that connects the world via the imagination with the understanding. In other words, what we may call ‘artistic research’ is not one dimensional (along the axis of the concept) but two dimensional (also along the axis of the idea), with the consequence that knowledge must either reduce what research delivers – say, to propositional form – or transform itself to cater for the epistemicity of proto-objects. It is the possibility of such a transformation that is currently being tested within academia if not Western culture at large.

The 2015 art installation ‘Proto-Objects’ engages with this space by continuing to develop the initial one hundred proto-objects through a number of collaborations into multiple transformations, which makes it even harder if not impossible to see what kind of representation could ever be adequate to the process of figuration that all proto-objects including the new ones now share.

References

Latour, Bruno. 1993. We Have Never Been Modern. Translated by Catherine Porter. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rheinberger, Hans-Jörg. 1997. Toward a History of Epistemic Things: Synthesizing Proteins in the Test Tube. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Schwab, Michael. 2012. ‘Between a Rock and a Hard Place’. In Intellectual Birdhouse: Artistic Practice as Research, edited by Florian Dombois, Ute Meta Bauer, Claudia Mareis, and Michael Schwab, 229–47. London: Koenig Books. http://www.researchcatalogue.net/profile/show-work?work=143845

Serres, Michel. 1982. Parasite. Translated by Lawrence R. Schehr. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.