CHANGING TERTIARY DANCE EDUCATION: THE BACHELOR'S PROGRAMME IN DANCE PEDAGOGY AT STOCKHOLM UNIVERSITY OF THE ARTS, 2020 - 2023

This exposition is part of the peer-reviewed article:

Østern, T. P., Reppen, C., O’Connell, S., & Daneberg, M. (2025). Choreographer/researcher/teacher: Developing a/r/tography as an approach to dance pedagogy at Stockholm University of the Arts in a professional learning community of teachers. Nordic Journal of Art & Research, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.7577/ar.5460

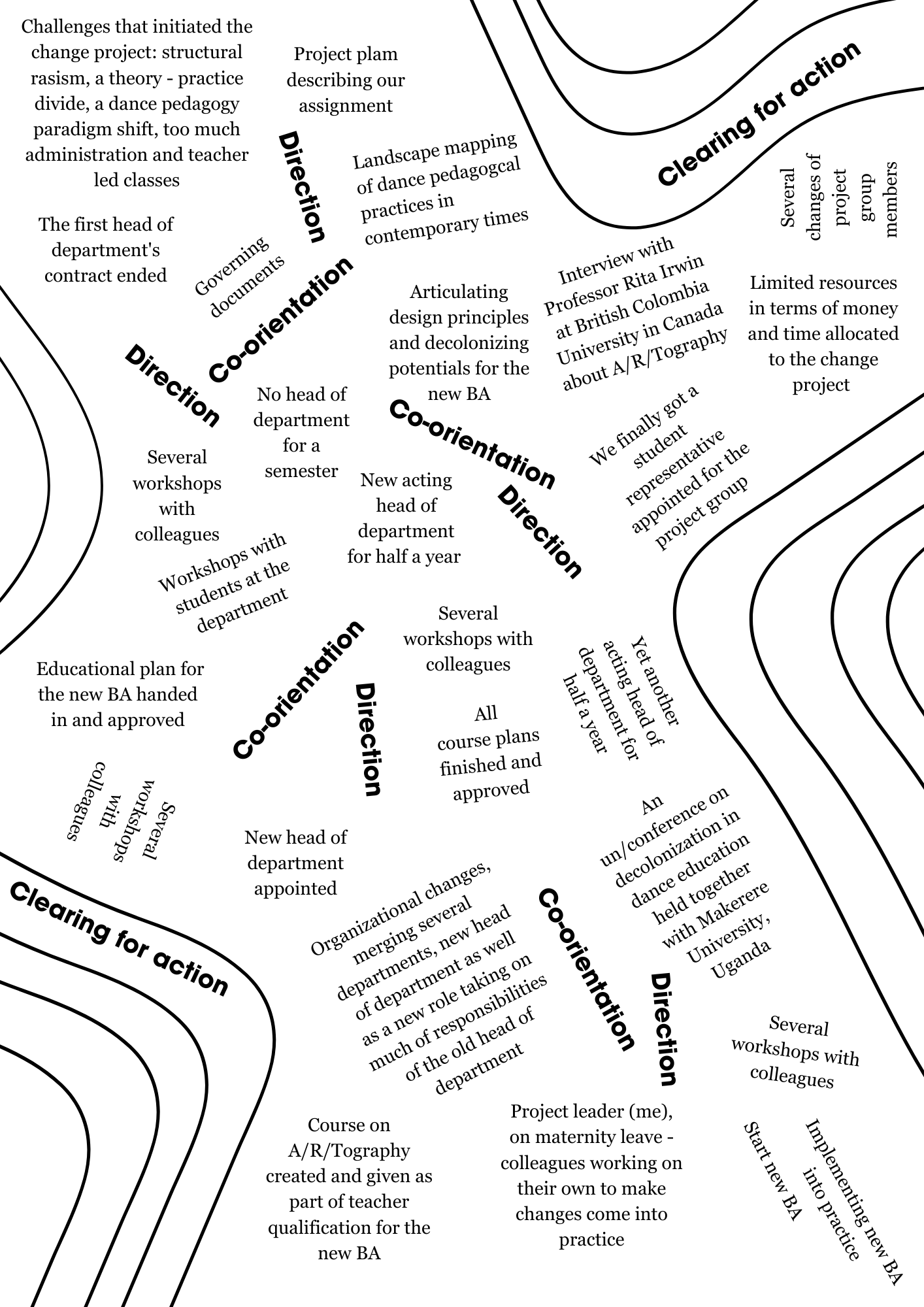

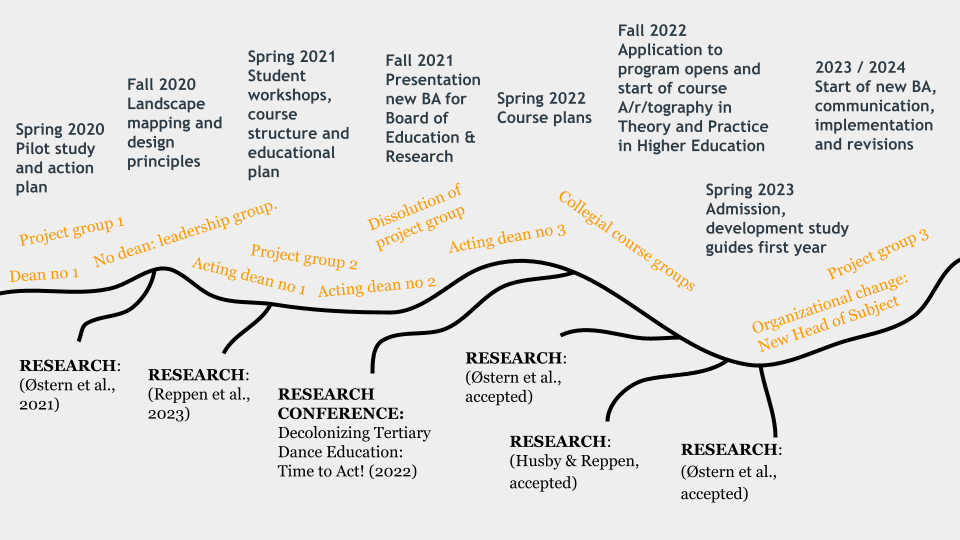

The exposition gives you an overview of the process of changing the Bachelor's Programme in Dance Pedagogy at Stockholm University of the Arts 2020 - 2023. It guides you through the phases of the change project, highlights important documents governing and forming the changes made, and links to research that were conducted during the project period and that deepened the knowledge created through the process.

The change project was an ambitious effort to work collaboratively in conducting a major change in higher dance education. I, Camilla Reppen, the project leader, created this exposition, which is why it is, at best, one partial account of what shaped and directed the process. The exposition is nevertheless an attempt to make the leadership choreography and creative logic of the change project visible, from my perspective.

As artist-teacher I practice an expanded notion of choreography (see for example Ingvartsen, 2016; Leon, 2022; Ölme, 2017) as I approach choreography with leadership practice, and conversely, consider choreography an approach to leadership for learning in change processes. The focus on leadership brings ethics into the choreographic process, and choreography as an approach to leadership evokes creative sensitivity (Pakes, 2018) into leadership practice.

Choreography might be understood as a process of social interactions connecting time, people, space and artifacts. Participants take part in unfolding a situation-specific creative logic through the assembling of parts into (temporary) 'whole(s)' (Pakes, 2018). If I diffract (Barad, 2014) this understanding of the concept of choreography with a relational perspective on leadership practice (Crevani & Endrissat 2016; Raelin, 2016), I suggest that the choreography of leadership practice encompasses an exploration of such an emerging creative logic supported by the definition of leadership as production of direction, co-orientation, and clearing for action (Crevani et al., 2010; Crevani, 2015, 2018).

This perspective on leadership emphasizes that it is processual and relational to its nature; that it is out of what we say, do and how we relate to each other and artifacts we create, as direction unfolds, which is what happens in leadership practice (Crevani et al., 2010; Crevani, 2015, 2018). Moment by moment through this change process, several different directions arose and the leadership choreography unfolded as a negotiation between these where direction in a larger sense evolved towards learning and change.

A relational and processual perspective on leadership highlights how construction of positions and positionings between different roles are created, recognized, and maintained (Crevani, 2015) - that is, how power is distributed and redistributed through social interactions. Through the positions and positionings established and reestablished through the working process, we co-oriented ourselves towards the aim and purpose of the change project, moment by moment.

The positions and positionings also affected clearings for action – spaces always already there, but also produced anew through social interactions in each moment (Crevani, 2015). Constrcution of issues (Crevani, 2015) concerning the specific conditions of the project (for example resources, time, and management changes) also affected these clearings and thus the ongoing production of direction through the project.

Nurturing an approach to and exploration of an emerging creative logic in the change process did not entail a right/wrong mindset, it rather offered possibilities to creatively find new connections and combinations of parts of the change process into new ‘wholes’ in the direction of learning and change. Inbetween the directions produced, the co-orientation and the clearings for action, the creative logic of this change project unfolded - and choreography happened.

The change project started with a project planning phase, defining the change project in its entirety. The assignment for the project planning was described in a project plan written by the Dean at the time (Alving, 2020). It was based on the challenges that sparked the initiation of the change project. Work done by consultants on anti-racism during autumn of 2019 also laid the ground for the project planning. The Higher Education Ordinance (1993:100) about degree objectives for bachelor's degrees in Sweden also guided our work.

The project planning phase ended with a comprehensive action plan that described the idea and phases for the whole change project.

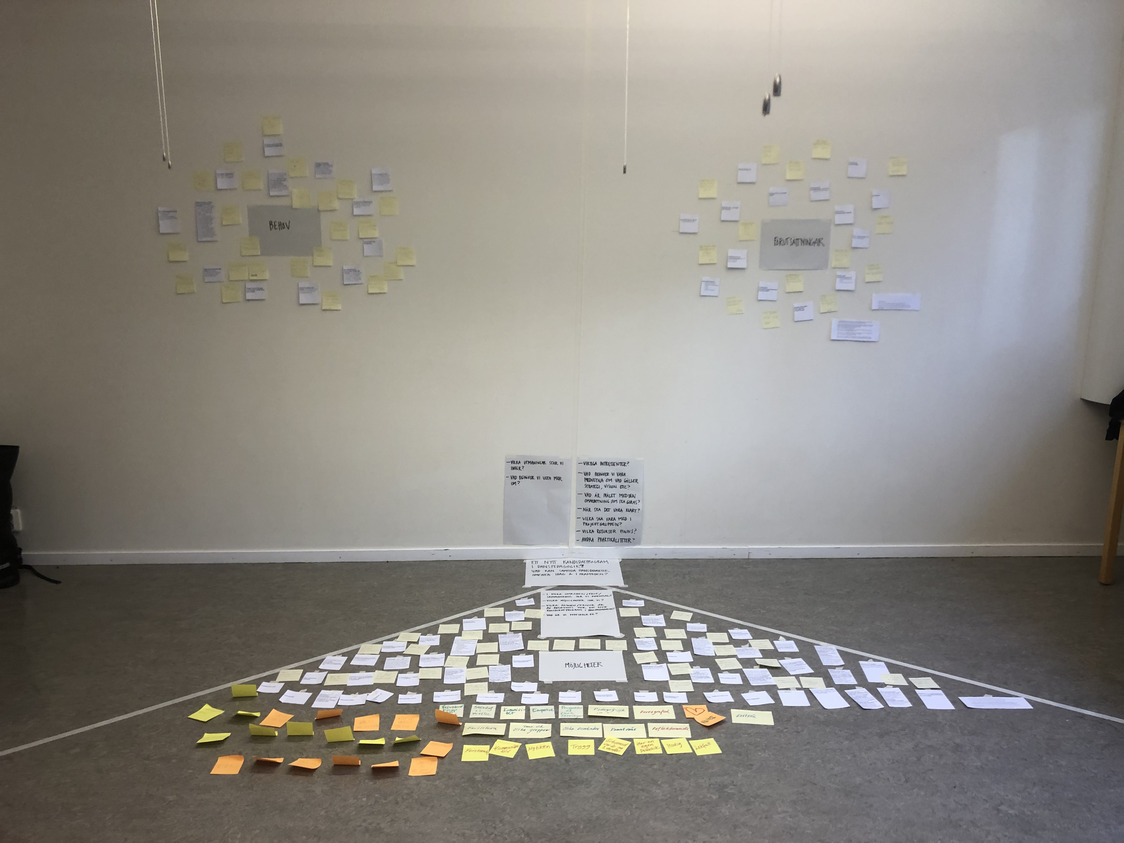

After the project planning phase, our first step was to listen into the field’s concerns and ideas about dance education today (Østern et al., 2021). We embarked on a major landscape mapping, supported by methods from the Futures Design Framework (Holsey Dyrman et al., 2018). We scanned the field for signals of change and created a collaborative map of dance pedagogical practices in contemporary times. What signals of change were appearing in the dance educational field? Where were we headed? We asked students, staff, alumni, and other colleagues in our field to collaborate with us in creating this map. Below you find examples of collected signals of change on scan cards made by staff, students and other respondents invited to join this landscape mapping. See also a presentation (in Swedish) of our work in progress at Stockholm University of the Arts Research week 2021 in the pdf to the right. The collection we managed to create was not exhaustive of signals of change in dance pedagogical practices at the time, but it gave a picture of what the respondents picked up. 140 scan cards documenting signals of change in dance pedagogical practices were collected and analyzed.

We also asked our consultants on anti-racism to suggest what to look for, and their input was to search for signals of change relating to representation and cultural appropriation, dance styles, genres, status and hierarchies, norm critical and anti-racist perspectives in teaching dance, norm critical and anti-racist perspectives in teaching dance teachers and norm critical perspectives and power hierarchies in general.

Example of scan cards collected through landcape mapping, written in both Swedish and English:

During autumn 2021 all design principles and insights gained through landscape mapping and workshopping with students and staff were developed into a new educational plan with course structure (Stockholm University of the Arts, 2022b) and background material for decision making (Reppen & Åhlén, 2022) . These documents were presented to the Board for Education and Research at Stockholm University of the Arts in December 2021. After minor adjustments the new educational plan was approved in autumn 2022.

For this phase, the project group had changed, and we were now a new group re-orienting ourselves towards the continuation of the project. A challenge for this phase of the change project had been identified as involvement of student voices and perspectives in the development of the new BA. Student perspectives and voices had a straightforward way of expression in previous phases of the change project through the documentation of signals of change on scan cards. A suitable platform for student voices and perspectives had not yet been established for the change project's continuation. Apart from the engagement of a student representative that was finally appointed for the project group, this challenge was something we needed to address further and more sincerely. It was decided that we should do a series of workshops during spring of 2021 to invite students to dialogue about ideas and questions that had been voiced concerning the new curriculum.

The documentation from the student workshop series can be found below (in Swedish). The work with involvement of student perspectives in the new curriculum was also explored in a chapter (Reppen et al., 2023) in the anthology Futures of Performance - The Responsibilities of Performing Arts in Higher Education (link through illustration to the right), edited by Karen Schupp.

The analysis process of all collected scan cards

consisted of the following steps:

During a workshop with the staff at the Department of Dance Pedagogy we looked at the collection of scan cards through a process of lateral thinking.

The students were invited through digital platforms to comment on the scan cards on what they saw and didn't see in the collection. Unfortunately, we didn't get any answers from students on the digital platforms.

Our consultants on anti-racism were also invited to analyze the scan cards for decolonizing potentials.

The project group analyzed the collection of scan cards specifically for decolonizing potentials and challenges as well as through other perspectives such as competences, places / contexts / fields, perspectives on knowledge, possible frameworks for the future program and what was not in the data collection.

The summary of all of this was presented in an internal, unpublished report (Reppen et al., 2021) to the leadership group of the Department of Dance Pedagogy (which temporarily acted as management of the department at the time). The report summarized the insights gained from scanning and analyzing dance pedagogical practices in contemporary times. According to the idea of Design Thinking (Koh et al., 2015), the insights were articulated in terms of design principles to help guide the development of the curriculum, and three different suggestions for structure of the future program. The different suggestions for structure were scenarios of overarching program structure and reflected three different approaches to the scale of the change we aimed for; pragmatic, progressive or radical change, respectively (Holsey Dyrman et al., 2018). We also reflected on what was missing in the collected data, what challenges we could identify going forth, and suggestions for internal development and tasks we needed to take on as staff. Part of the analysis process was presented in a research article (Østern et al., 2021) (link through illustration above) about decolonizing potentials and challenges identified in the collection of scan cards.