The Bass Guitar in the Contemporary Music.

-

Full name: Andrea Dettori

-

Main Subject: Double Bass, Classical

-

Student Number: 3212025

-

Date: 8/03/2021

-

Research Supervisor : Enno Voorhorst

-

Master Circle Leader: Anna Scott

-

Main Subject Teacher: Quirijn Van Regteren Altena

-

Research Question: Can the electric bass guitar rise to the role of solo instrument in contemporary music?

-

Format: Exposition

Table of Contents

1) Introduction

-

1.1 Introduction to the Research

-

1.2 Method

2)The Bass Guitar

-

2.1 History of the Bass Guitar

-

2.2 Luthiery

-

2.3 Electric bass vs Double Bass

3)The Bass Guitar in the Contemporary repertoire

-

3.1 “Bass”Composers

-

3.2 The relationship between Performers and Composers, Quirijn van Regteren Altena interview.

-

3.3 Jaco Pastorius, The missed Reference on Contemporary music.

4) New creation

-

4.1 Introduction to the new piece “ L’autodidatta” by Maurizio Tedde

-

4.2 Video of the performance

-

4.3 Analysis of the Piece, explanation in details of the technique,excerpts

-

4.4 Interview to Maurizio Tedde

-

4.5 Feedbacks from the Audience

5) Conclusion

-

5.1 Feedback from the audience

-

5.2 Conclusions

-

5.3 Future Project

6) Sources

1) Introduction

1.1) Introduction to the Research

The following research stems from a personal desire to incorporate my background as an electric bass player which has always remained outside of my double bass studies. In fact I started my personal musical career as a bassist in pop, rock and blues contexts and only later in life approached the double bass in the classical world. I have always kept these two worlds separate as they are very different in form, attitude and style. It was only during my time studying here at The Hague Conservatory that I had my first in depth experience with contemporary music. I then had the opportunity to talk and eventually collaborate with some composition students, discussing the strengths and possibilities of the electric bass in contemporary music. Exploring the repertoire I found that few composers have used the electric bass as a means to support the harmonic foundation in an ensemble replacing the double bass, but above all, very few have thought of the electric bass as a solo instrument with the means to convey expression and language in a classical context, restricting the possibility of the electric bass to impose itself in new repertoire. From this fact emerges the question of my research:

Can the electric bass guitar rise to the role of solo instrument in contemporary music? How can it find its way to be considered as a solo instrument in contemporary music? Can composers approach this instrument exalting its expressiveness and technical potential ?

This research would like to address these questions through a cultural investigation of the impact of the electric bass on the world of pop music and jazz, why it was effective and how it has and continues to inspire the music of contemporary composers and whether their inspirations benefited the instrument. This investigation helps to understand why there is not a concept of the bass guitar as a solo instrument. After this journey discovering the recent past of this instrument and its place in the realm of Contemporary music, I will focus on a real world creative and compositional process which will end with the creation of a newly composed piece for electric bass and electronics written by a former student at the Conservatory of The Hague, Maurizio Tedde. This piece demonstrates that it is possible to put the electric bass guitar at the centre of a compositional process.

The research does not solely represent an isolated view of my present musical self, but rather is a way to open up to an aspect of my musical identity that I have been carrying around with me since I first started playing music. Through conducting this research, I try to realise the potential of the electric bass in the contemporary context,and wish to share the knowledge that I have acquired by interacting with the electric bass. I want this to be a resource for composers who want to embark on a compositional process with this instrument. My hope is that by showing the new generation of composers this Research, it can create an impulse that can help develop the reputation and increase the use of the electric bass in new repertoire.

1.2) Method

-

Reading: Books and articles about the life and style of different composers and performers that I will mention in the various chapters of the research.()

-

Interviews: I will interview composers and performers to understand how they collaborate with each other, to understand different perspectives

-

Analysis: I will examine and practice extracts of the chosen works and analyze them through videos describing techniques and musical choices.

-

Collaborating: I am going to collaborate with the composer, Maurizio Tedde. He composed a piece for Bass Guitar and Electronics. I will describe our collaboration process.

-

Recording of this new piece: I will create a studio recording and video of the new piece. Maurizio Tedde will assist and collaborate with me through both processes

-

Collect Feedbacks: The video recording will be submitted for listening with a short questionnaire to be filled in, in order to discover and obtain confirmations of the validity and credibility of the piece and of the use of the electric bass in it.

2) The Bass Guitar

2.1) History

To speak in detail about the electric bass we must note that its birth, as we will see below, was due more to practical needs as opposed to musical taste.It was only later in the following decades in different areas such as Jazz and Pop that the choice of using either the electric or double bass came from a specific stylistic choice. The double bass, as we all know, developed from the family of viols and has continued to undergo constant evolution, from its size and shape to the changing material of the strings, from gut to steel, which have all resulted in fundamental improvement of performance, playability and effectiveness in its role in the ever changing orchestral setting. In America this constant quest to improve the quality and ease of the double bass translated into a focused strive for audibility. The double bass was used as the foundation in jazz contexts, especially in Swing big bands and for the first 30 years bassists spent a lot of energy in making the double bass as audible as possible. These courageous attempts were often overpowered by the huge number of woodwinds in the band. This problem could also be found in the 40’s and 50’s, when big bands began to shrink into small club formations and both guitar and drums (the main stage companions of the double bass) underwent constant technological innovation. The drums became bigger and bigger while the guitar became easily amplified. [1]

During this period of time, between the twenties and the fifties some musical instrument production companies tried to solve this problem, often intervening with radical adjustments to the double bass in both form and playability.

Some attempts were made to put some electric double basseson the market in the 20’s, such as an electric double bass defined by its slim design created by Lloyd Loar, an engineer who worked at Gibson Mandolin Guitar. This company also produced the Mandolin Bass, which was used as a bass instrument for mandolin orchestras and was an early ancestor of the electric bass. In the 30’s Rickenbacker tried to introduce an electric double bass in the shape of a stick. In Chicago they had little luck with the Regal Bassguitar, a kind of Double Bass with guitar-like frets, which also tried to solve once and for all the intonation problem that often plagued double bassists of that time (and still continues to plague us till today). All these attempts had no luck and these instruments have become a unicum and are now almost impossible to find.

Another good try was from Everett Hull of Ampeg amplification system. This Brand of bass amplifiers, very famous even today, had some success in trying to amplify the double bass by directly inserting a microphone into the spike (amplified peg, from here the name Ampeg).

But the first instrument to use the shape which we could now identify as a proper bass was the Audiovox Bass in 1936. This was an instrument created by a Hawaiian guitarist living in Seattle. It had a very minimalist design, with only one pickup and very small sized solid body. In fact, its main purpose was to improve portability and practicality with a reduced physical bulk compared to the double bass. However, for some reason this instrument was not able to break into the market as what happened to the model “Precision” by Leo Fender, which would be destined to mark the characteristic sound of the electric bass for decades.

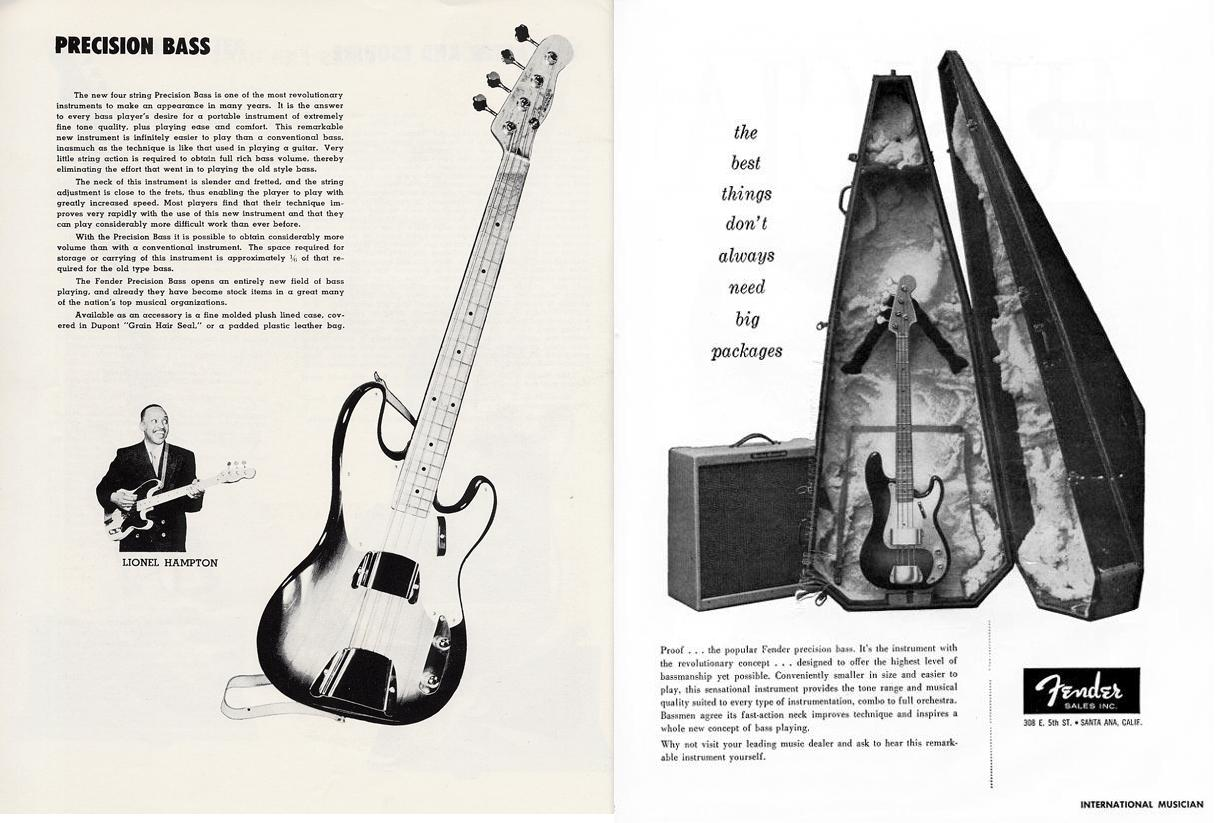

Clarence Leoinidas Fender (1909-1991) was born in a barn near the Anaheim-Fullerton border in the Los Angeles Area. Here in 1945 he first started his business with Doc Kauffman founding the company K&F which produced electric lap-steel guitars and amplifiers. Doc left after one year due to the precarious financial instability of the project and so Leo renamed the company Fender Electric Instrument Co. and subsequently launched his Fender Precision model in 1951. The shape was reminiscent of the existing guitar model (Telecaster) and was called “Precision” to emphasize the precision of intonation compared to the double bass. Don Randall, a Fender distributor in the early 50s, explain :

“Leo and I had a discussion about the new bass and He’s telling me how precise it was, how you could fret it right down the hundredth of an inch, Now who puts their finger a hundredth of an inch this way or that way on a bass string? But he was so possessed with the fact that this was the first time that the fret layout on a bass was so precise. He said to me"you know, it’s so precise we ought to call it the precision bass." Well, why not? So it became the precision bass” . [2]

The purpose of this bass guitar was to simplify construction and innovate its shape(which will be modified later with the new models). Leo Fender focused a lot on the feedback that he received from as many musicians as possible, developing an easy product: to repair, to transport, to amplify (Fender produced the Bassman, amplifier used at the time).

Since the coming of the Fender Precision more and more brands began to produce electric basses, Gibson Rickkenbucker Hofner etc [3]…

The final consecration of the instrument took place in the second half of the 50’s From this moment on the Double Bass was no longer necessary as the bass foundation of a band but on the contrary became a stylistic choice.

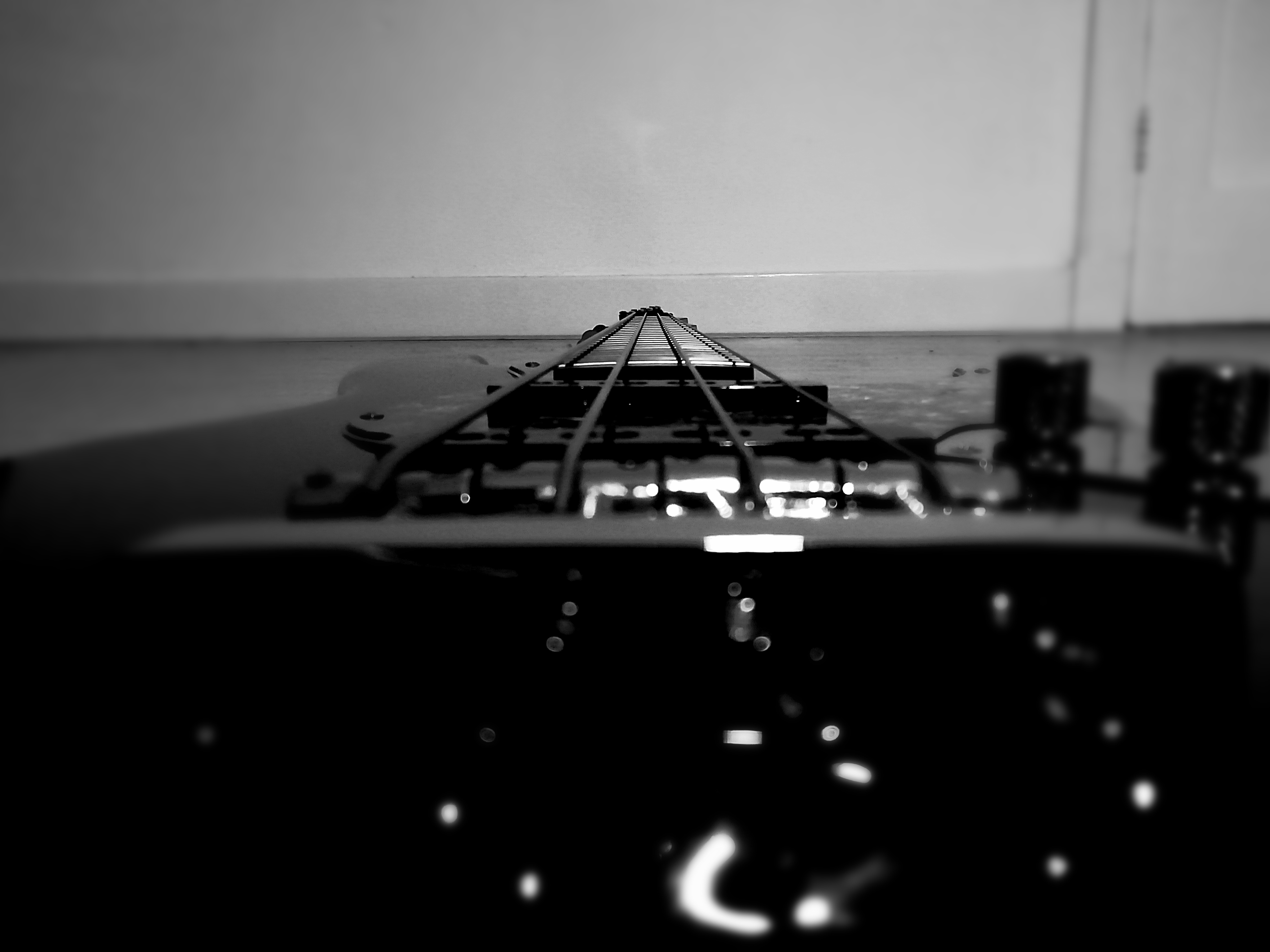

2.2) Luthiery

Solid Body

The structure of an electric bass usually has a solid body. The shape, the quality of the wood used and the type of insertion of the neck onto the body affects the sound quality. In fact, by either constructing the body in layers or in a single piece of wood affects the compactness of the wood and therefore highly influences its sound quality. Finally, the body is varnished with an opaque or satin finish, highlighting the grain of the wood.

Neck

The neck is made up of frets that allow the desired intonation and allows the passage of the strings. Made of maple, it usually ends on one side with the body of the instrument and on the other with the headstock which, by means of the mechanics, allows the strings to be pulled and tuned to the desired tension.

Fingerboard

The fingerboard of the electric bass has a wooden surface (maple or rosewood) on which you can press the strings onto to vary the pitch of the notes produced. The fretboard of the electric bass can accommodate the frets or be without them as with the fretless bass. Normally, keyboards can contain 20 to 24 frets. On a 4-string bass it is normally tuned in 4ths (G-D-A-E)Each fret defines the advancement of a semitone of the produced note. The fret is a slightly raised metal bar inserted into the fingerboard perpendicular to the strings.

Strings

The strings of the electric bass are mainly made of steel, with a solid core. The most used materials are steel or nickel, with differences in timbre between the two options. In some cases the metal strings can be coated with a synthetic material. Another important element is the type of winding, which determines the type of surface of the string, which can be rough, semi-smooth and smooth. Some experimental bass models feature silicone strings. Basses have either four or five strings, with the following tuning: G, D, A, E and B in the presence of the V string (in order of pitch from the highest to the lowest).

Circuitry

All electric basses have a circuitry that allows control over the volume and sound frequencies of the instrument. The circuitry is divided in two categories, ACTIVE and PASSIVE.

-

In passive circuits, the circuitry is simply composed of potentiometers and capacitors, which can change the volume and “cut” the frequencies. The sound of the instrument in the form of an electrical signal is then conducted to the amplifier by means of a shielded cable.

-

Active electric basses have electronic circuitry powered by batteries. This allows the system to equalize the sound with more sophisticated active filters, giving it the ability to increase or decrease the level of the set frequencies even up to 20 decibels. This usually allows one to intervene on two or three bands of equalization and are powered by one or, more rarely, by two 9 volt batteries. Generally these instruments have a circuteria only “active” or “passive”, however, some models are able through a selector to use both.

Pick up

-

The electric bass is amplified by pickups. Pickups can come in three different types:

-

The split-coil (called “Precision” or “P” type), consisting of two coils each with 4 magnets (two per string).

-

The single-coil (called “Jazz type” or “J”), consisting of a single elongated body that affects all the strings. Over time, as the sound needs of artists changed, other types of pickups were added:

-

The humbucker devised by Ernieball “MMH”, consisting of two parallel windings with 2 magnets per string and the “Soap-Bar” format (cover narrower than that of the MMH, can contain inside any type of pickup).

-

Usually the pickups are “passive”, but some models, such as StingRay, almost all Music Man basses and the EMG, have an integrated preamplifier that requires dedicated power supply.

2.3) Electric Bass vs Double bass

As mentioned above, from the moment the electric bass started being used, especially with the coming of pop and rock , the electric bass had an immediate impact in the sound of a band. Particularly in these genres the double bass became more rarely used, with some exceptions that can be found in certain paths of rock and roll, particularly in rockabilly. In fact there is a double bass resistance thanks to ‘slappers’ of the upright bass players (such as Marshall Lytle with Billy Hailey, Bill Black with Elvis Presley or Jack Neal with Gene Vincent just to name a few ). But by now the electric bass, both in the imagination and in practice, has acquired more and more importance.

A very different process happened in the Jazz world. In fact the double bass is preferred to the electric bass for its tradition, style and use. It was only after Jaco Pastorius revolutionised the electric bass that it was able to create its own dimension in the world of Jazz. This is also thanks to the nature of Jazz becoming open to new styles (funk above all). It brought soloists and composers who pushed the limits of the electric bass, creating its own space without undermining the double bass.

What happened with classical music instead? The role of the Double Bass for obvious reasons cannot be replicated by the electric bass, and practicality has never trumped the sound quality that composers wanted to achieve. But it is in the contemporary repertoire, thanks to individual influences and the vision of some composers, some new and non-traditional instruments have been implemented in modern ensembles.

The electric bass, however, in the contemporary repertoire has an almost “irrelevant” importance compared to its brother the double bass. Why? What has stopped this pursuit of knowledge about the instrument? Why this lack of curiosity and exploration? Why are there no solo electric bassists in the contemporary repertoire?

All these questions form a bigger set of questions: Can the electric bass be a solo instrument? Can a composer use the electric bass as a means to expressively realize himself?

To reveal the answer to this question first we must contemplate the role of the electric bass in contemporary music. We will try to identify some composers and bring to light their approach to the electric bass.

3) The Bass Guitar in the Contemporary repertoire

3.1) “Bass Composers”

There are some composers who have used the electric bass in their repertoire to entrust the bass register to this instrument. During this analysis of the contemporary bass guitar repertoire it has been fascinating to see how several composers coming from a so-called classical environment have received the same inputs and influences from the world of Jazz, Pop and Rock but at the same time have translated into a totally different approach to the electric bass guitar.

Obviously the approaches change for reasons related to the background, influences and musical tastes of the composers, the compositional attitude, the cultural and musical and even political environment these composers belonged to.

I could easily mention Frank Zappa, a composer now also performed by contemporary ensembles and considered with attention by the cultured music audience.But my intention is to look at how composers who belong to the classical music world can be influenced by a different context. Frank Zappa came from that world considered somewhat alien by “the Academy” and knew exactly how to treat electric instruments such as electric guitar and electric bass. It would be interesting to conduct a research on how Frank Zappa approached the so-called traditional instruments but this topic can’t find space here.

The composers I decided to analyze are all profoundly different from each other:

-

Fausto Romitelli

-

Alfred Schnitkke

-

Louis Andriessen

For the first two composers we are going to examine in detail some significant bass excerpts in their works, accompanied by demonstration videos using extensive techniques trying to analyze and codify different styles in sound and language. Regarding Louis Andriessen, I decided not to focus on one piece in particular. Louis Andriessen has written numerous pieces featuring the electric bass, some of which are quite difficult to play. However, I think it is more important to understand his approach as a whole, to understand the conception of the instrument in the contemporary context. In order to understand this we will analyse the role of the Hoketus Ensemble and give voice to a bass player who collaborated with him on many occasions. My detailed analyses are absolutely not intended to give a negative or positive judgement of the compositional process that characterized them. I would like to focus from a bassistic point of view, the one of the interpreters. Trying to discover and understand if there is a real reason why the electric bass is rarely used in the repertoire.

Romitelli, an index of Metal

Fausto Romitelli (1963-2004) was an Italian composer born in Gorizia. He graduated from the Conservatory of Milan in composition and studied at Ircam in Paris Cursus d’Informatique Musicale. His attention turned to the most important European musical figures of the time (in particular, György Ligeti and Giacinto Scelsi), but his main source of inspiration was the French spectral music, in particular Hugues Dufourt and Gérard Grisey. Romitelli himself describes his compositional style :

“At the centre of my composing lies the idea of considering sound as a material into which one plunges in order to forge its physical and perceptive characteristics: grain, thickness, porosity, luminosity, density and elasticity. Hence it is sculpture of sound, instrumental synthesis, anamorphosis, transformation of the spectral morphology, and a constant drift towards unsustainable densities, distorsions and interferences, thanks also to the assistance of electro-acoustic technologies. And increasing importance is given to the sonorities of non-academic derivation and to the sullied, violent sound of a prevalently metallic origin of certain rock and techno music”. [4]

He departs from avant-garde music through an investigation of the sound and gesture typical of rock and progressive music. He was always fascinated by popular culture, particularly rock and electronica. The sound of his larger ensemble works have something grainy, distorted and artificial, influenced by the electronic music of the nineties and artists like Aphex Twin, an important figure in contemporary electronic music.

We can notice the presence of the electric guitar and electric bass, as in the trilogy of “Professor bad trip” or the piece for electric guitar only “Trash tv Trance”. He brought these rock and pop instruments in a “Cultured” context.

We will focus on his last work before his untimely death.

An Index of Metals (2003) is a video opera for soprano, ensemble, electronics and video projection. The video projections are by Paolo Iachini with texts by the poetess Kenka Lekovich. The ensemble has the following instrumentation as follows: Flute,Oboe, english horn, clarinet, bass clarinet, violin, viola, cello, Electronic, electric guitar, electric bass, Jpiano, sampler, trumpet, trombone All instruments are amplified.

Romitelli’s sound was focused on 6 different aspects. As the composer himself states:

My compositions take as their starting point the idea that sound is a matter that can be worked.The grain, thickness, porosity, density, brilliance and elasticity are the main aspects of these sound sculptures resulting from amplification and electro acoustic treatment as well as simple instrumental writing

He further adds:

“… An Index of Metals is thus not simply another attempt to the new operatic genre by adding a visual element to the production, nor is it a strictly multi-media approach in which each artist contributes to a common narrative. It is, rather, a completely new concept in which sound and light become part of a single through process, like music and video, where timbre and images are used as elements of a single continuum subjected to the same computer transformations. The story is that of the fusion of perception, the absence of landmarks, the henceforth limitless body in the furnace of a ritual mass of sound. Even the original libretto by Kenka Lekovich is transformed by being translated from one language to another. The music for sopranoand eleven amplified instruments develops an impure timbre through counterpoint with the colourful interference in the video by Paolo Pachini and Leonardo Romoli. Three autonomous films, projected on three screens, take up all the visual space, while the sound is projected as patches of light. Both music and image use the same physical characteristics, including the irisation, corrosion, plastic deformation, rupture, incandescence and solarisation of metallic surfaces, thus revealing their inner violence and even murderous tendencies.” [5]

His influences in the field of psychedelic rock are quite clear in this piece which opens with a slow drone of the opening G-minor chord of “Shine on You, Crazy Diamond” by Pink Floyd. The guitar and electric bass are entrusted with a constant layer of “matter”, a sound carpet that extends throughout the piece.

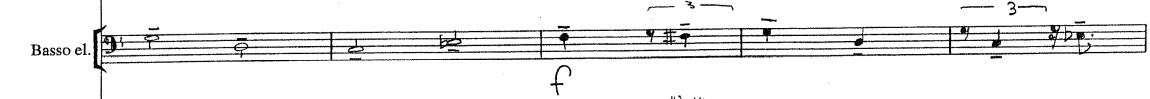

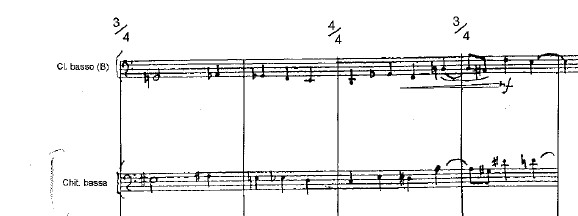

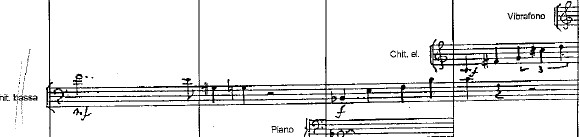

Bass excerpts:

- Col legno

In this particular passage Romitelli decides to create a very dense sound texture, trying not to let the listener guess the sound source. The bass is played with the wood of the bow exactly above the fret, with a simple circular movement so as to make the intonation oscillate slowly and softly. In this case I replaced the bow with a cup, much easier to play and to control obtaining the same sound.

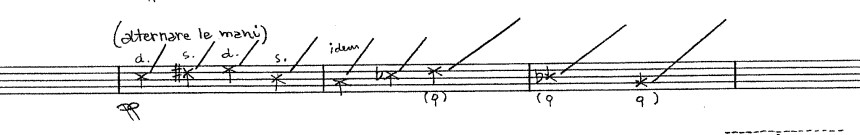

- Alternate hands

Romitelli here asks for a light tapping on the “pianissimo”, alternating hands allows a quick glissato. By alternating the hands with tapping you can see that the bass is not played with the traditional right hand pizzicato technique.

- Slap

This technique is based on the gesture of “pulling” the string so that it slaps back into the fretboard. You can compare this technique to a typical Bartok pizzicato. Usually this technique is played “forte”. Romitelli requires the performer to form a crescendo from the pianissimo, a technical musical oxymoron for the slap technique.

- Mani alternate e raschiato (alternating hands and scraping)

On this occasion Romitelli combines the technique of alternating hands with scraping with a pick (or nail). In this video I use a coin to create an even more effective scrape.

- Chords

The composer uses the bass with the fourth string tuned in D. At this juncture one can appreciate the depth that the electric bass can give to the musical fabric, arousing gloom and, anxiety.

- Harmonics

In this fragment the composer highlights the crystallinity of the harmonics. In fact, they are very direct and intelligible to the listener, one can notice even in these small moments the composer’s knowledge of the instrument.

Alfred Garrievich Schnittke,Seid nüchtern und wachet

Alfred Garrievich Schnittke (1934-1998) was born in Engels, southern Russia. On his mother’s side he was of Volga German and Roman Catholic extraction, on his father’s side he was German-Jewish. His peculiarity that distinguished him from the composers of the USSR was attained during his time in Vienna from 1945 till 1948, acquiring cultural and musical traits of the Austro-German tradition. He entered the Moscow Conservatory in 1953, completed his postgraduate work in 1961, and since then had earned a living, partly by teaching and partly writing for the cinema.Influenced by the rebellious modernism typical of Moscow in the early 1960s, Schnittke embarked on a journey of compositional discovery by embracing the modernist and avant-garde fascinations of the time.His works fused Soviet symphonic technique with highly parodistic and experimental traits making him much hated by the central committee and loved by the underground scene that went against the party. These traits led him to be one of the most performed Russian composers, also thanks to his personal friendship with some stars such as Yuri Bashmet, Gidon Kremer and Rostropovich, for whom he composed a lot of music. [6]

Even during the post-stroke years he was characterized by his works with a strong religious and satirical, almost dark component. Faust Cantata is the typical piece which reflected the stage of his carrer at this moment.

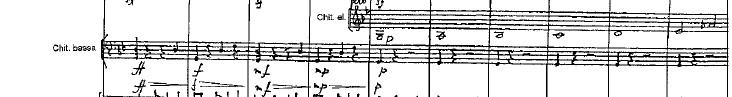

“Seid Nichtern Un Wachet”, is a Cantata for Alto, Counter-Tenor, Tenor, Bass, Mixed Choir and Orchestra.

It features an unusual combination of soloists and a full orchestra including drums, electric guitar and electric bass. Schnittke worked for 12 years on the complete opera Historia von D. Johann Fausten; the cantata was a commission for the 1983 Wiener Festwochen, based on the literary work of Thomas Mann [7].

His ability to recall several styles (through the cantata we will have western references with swing and tango atmospheres) leads him to the use of instruments typical of jazz and pop music such as electric guitar, drums and electric bass. A russian musicology describes:

Adrian’s capacity for mocking imitation, which was rooted deep in the melancholy of his being, became creative here in the parody of the different musical styles in which the insipid wantonness of hell indulges: French impressionism is burlesqued, along with bourgeois drawing-room music, Tchaikovsky, music-hall, the syncopations and rhythmic somersaults of jazz – like a tilting-ring it goes round and round, gaily glittering, above the fundamental utterance of the main orchestra, which, grave, sombre, and complex, asserts with radical severity the intellectual level of the work as a whole. [8]

The orchestration of this work is extremely complex, complete and rich:

3 (also picc.) 3(also c.a) 3(also alto- and baritone sax.) 2 cbsn. - 4 4 4 1 - timp., perc. (cymbal, tambourineo, tamburo, tom-tom, gran cassa, tam-tam, flexaton, xyl., vib., marimba, campane): 6 player - electric guitar and bass guitar, cel., pno., hpsd. - str.

The libretto was originally written in German but is also performed in Russian.

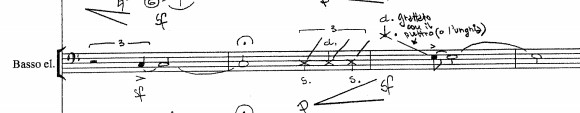

I have selected two moments during the cantata where the bass plays a fundamental role:

- Andante poco pesante (24)

The bass plays a very simple pizzicato passage that accompanies the vocal bass solo almost like a walking bass. The walking is shared with the bass clarinet. The orchestral structure is very bare and the bass solo combined with the accompaniment of the electric bass makes the atmosphere very gloomy.

- Tango, Es Geshash

The climax of the opera’s pathos and tension is reached in movement VII, Es Geshash. It results in a diabolical Tango in both music and text, entrusted to the mezzo-soprano.

The electric bass here keeps the tango’s gait and is characterized by glissati together with the electric guitar that seem to accompany the movement of the typical Argentinian dance.

Louis Andriessen and The Hoketus Ensemble

Louis Andriessen (1939) is the most prolific Dutch minimalist composer. He was a teacher in the composition department here at the Royal Conservatory. He is one of the founders of the Haagse School together with his colleagues Jan van Vlijmen, Diderik Wagenaar and Gilius van Bergeijk.

For the purpose of this research it is very important to mention one of his most innovative ideas: The Hoketus Ensemble.

The Hoketus Ensemble is considered a unicum in the history of contemporary Music. It is an Ensemble composed of students of the Conservatory in 1976, and they concluded their adventure with a last concert in 1987. They gathered to perform the music of Louis Andriessen which was composed ad hoc for the ensemble. The Hoketus was unique due to its special instrumental composition. The ensemble was composed as follows:

2 piano, 2 fender rhodes, 2 Sax, 2 panflute, 2 Bass Guitar, 2 percussion.

The peculiarity of the ensemble was based on strict rules that the musicians had to follow to the letter, creating a real Manifesto:

-

High amplification volume.

-

The two groups of musicians were positioned apart from each other almost as though reflected.

-

Personal expression was banned.

-

The melodies could only be constructed through the interlocking of single notes or chords, played alternately between the groups using the medieval technique of hocket ( here a nice thesis by Mary E. Wolinski The Medieval Hocket).

The pop and rock background of some of the musicians (influenced by Pink Floyd, Talking Heads, Beatles, along with the amplified instruments which gave a pop approach to the sound and a conception of the Beat which was very far from swing. These sounds were combined with the sound of panflute and sax, and thanks to Andriessen’s compositions, you could appreciate a totally new sound, which ranged from hard rock to Igor Stravinsky, one of Andriessen’s favorite composers.

The dynamics were mainly forte, without nuances of any kind by the Ensemble’s own choice. Other composers aside from Andriessen also composed for the ensemble , however it seems that the interaction between composer and Hoketus Ensemble did not always go well, due to the difficulty of adhering to the Hoketus Manifesto. On Youtube we can view a documentary produced by Bas Andriessen, where the members of the ensemble are interviewed, identifying the group dynamics inside the ensemble which ultimately led to the drafting of this manifesto. The sounds sought after by the ensemble with their very different instrumental combinations had a strong cultural impact in The Hague and in Holland.

Innovations

The ensemble brought instruments belonging to the pop world to the Dutch music scene , especially fender rhodes and electric bass. Their presence made the project itself innovative, alternative and distinguishable, giving a new perspective to all contemporary music and presenting new visions to be absorbed by the future generation of composers. This attitude can be seen in other works by Andriessen where he decides to use the electric bass (such as one of his most famous works De Straad). Louis Andriessen decided to use the electric bass on many occasions during his career. Mainly moved by the fact that Andriessen’s wife Jeanette Yanikian was playing the Bass guitar Andriessen however left room for the instrument in his other post-Hoketus ensemble works as well. Did the electric bass have room to develop its potential in Andriessen’s music?

Andriessen’s great merit is that he brought unconventional instruments into the cultured scene.

Undeniably his approach to the world of amplified instruments was crucial to enticing other composers to make the same choices. The mere consideration of incorporating the electric bass is synonymous with innovation. The Hoketus ensemble, due to its intransigent rules, did not have room to discover the potential and explore the subtlety of expression capable from the instrument. So for obvious reasons the ensemble was not a suitable place for the instruments and for any introspection of what they could do.

3.2) The relationship between Composers and Performers

As we noted in the previous chapter we can deduce that the electric bass, especially in an ensemble context, can be used in many different ways. Andriessen used it as an engine together with other instruments, often constructing an obsessively repeated rhythmic pattern. Romitelli searched for new timbres through the use of the bow and Schnikkte sought for a connection with the popular sphere looking for the sound connections between “academic” and pop music.

In the history of music the continuous research and speculation regarding the potential of a musical instrument at an expressive and technical level has pushed its barriers beyond all limits. A good example of this process is in the double bass., Thanks to the recent curiosity developed by the composers, it has managed to evolve its technique, its expressiveness and is now standing out on a par with the cello and violin as a solo instrument. The double bass is achieving this result not only thanks to the curiosity of the composers but above all thanks to the synergy of the soloists, and this process is also taking place in the orchestra or ensemble

Did the same process happen for the electric bass?

The interview with Quirijn van Regteren Altena, Double Bass professor at the Royal Conservatory of The Hague and long time double bassist of Asko Schoenberg Ensemble, is crucial to shedding light on the relationship between composers and the electric bass and is useful in identifying the reasons for the lack of development in the repertoire for the electric bass . Indeed, Quirijn during his early career had the opportunity to be the electric and double bassist for composers such as Andriessen, Steve Reich and John Adams. Particularly with Andriessen he had the opportunity to experience first-hand how the electric bass was conceived in his compositional process.

- What was your first approach to music, and how did you enter the bass guitar world?

Quirijn began his musical education at a very young age with the piano at the age of 7. At the age of 13, his first contact with the bass and double bass took place at the same time thanks to the influence of his cousin, a jazz double bass player. He was one of the first electric bass players in contemporary music but when he realised that the study of electric bass had reached high standards with the advent of Jaco Pastorius and the limit it represented he decided to concentrate purely on the double bass.

- Describe your first years of career, in which ensemble did you play?With which composers did you have the pleasure to collaborate?

In this answer Quirijn talks about his musical environment in his early days, from Dutch youth orchestras to his first jazz experiences and playing electric bass in bands. In this video Q talks about and describes his collaborations with minimalist composers, in which a certain electronic nature was involved: Louis Andriessen, Steve Reich and John Adams.

-

Andriessen: Quirijn participates as Bass Guitar player in a theatre production with a piece written for drums, electric bass, guitar, synthesisers and electric clarinet.

-

Steve Reich: Participates in the first European tour as the double bass player. Very interesting anecdote in which Steve Reich, answering a question from Quirijn about the use of the electric bass in his future compositions, asks Quirijn what is the right tuning of the electric bass.

-

John Adams: With John Adams he has the pleasure of playing the famous opera “Nixon in China”. They never had any discussions about the use of the electric bass. But in Nixon in China he sensed a certain need for John Adams’ pushing of low frequencies, even though they came from synthesisers.

- Did the composer give you room for manoeuvre and personal vision playing the bass guitar?

Quirijn describes a concept already addressed in the section on The Hoketus Ensemble. The use of the electric bass was in itself very innovative and there was no desire by the composers to develop it as a solo instrument. There was more of an ambition to achieve a certain sound rather than virtuosity.

- Did you ever have the feeling that the electric bass could replace the double bass in the contemporary repertoire?

At the beginning of his career, Quirijn believed in the possibility that the electric bass could replace the double bass. Indeed, new compositions were aimed at amplifying the instruments, and the electric bass seemed the natural solution. At the same time he identified two reasons why this change had never taken place in the history of chamber and orchestral formations:

- The composers’ need to get as many performances of their pieces as possible, which led to a choice of more traditional instruments such as the double bass.

- The lack of clarity and conception of the electric bass by composers.

- Few quality bassists interested in contemporary repertoire.

- The ease of replicating the electric bass with synthesisers or keyboards.

- Your career with the Asko has led you to be recognised more as a double bass player and not as a bassist. Why has your career gone in this direction?

Quirijn briefly explains how his bass career went in the direction of double bass, where he obtained many collaborations with composers for solo double bass pieces.

- Do you think that the lack of solo emancipation of the double bass depends on the fact that the composers were “deaf and blind” to the sound and creative input of the soloists at the time?

With this answer Quirijn defends the category of composers against my deliberately provocative question. In fact, the role of the electric bassist and especially the good electric bassist was not that of a soloist. And the only identifiable exception in Jaco Pastorius was very difficult for the more established modern composers of the time to grasp. At the same time, bassists were not interested in that kind of compositional approach, relying on a composer to improve and explore the potential of the instrument.

- What future do you see for the electric bass guitar in contemporary music? Do you think that there is currently a good environment for the compositional development of this instrument or that there is a lot to do?

At this juncture, there is a very positive response for the future of the electric bass in contemporary music. There is room for development and, above all, the collaboration between composers and performers within institutions such as the Royal Conservatoire may give rise to a new solo perspective for the electric bass.

3.3) Jaco Pastorius,The missed reference in Contemporary Music

The style of Jaco Pastorius (1951-1987) has been crucial for entire generations of bass players and still is a constant reference point of absolute technical and compositional execution that has as its starting point the electric bass. Pastorius’ first record is not only a testament to his virtuosity but also to his ability to touch as many styles. Bebop, R&B, Afro-Cuban-influenced trance music, Caribbean-flavored Florida funk and orchestral music with contemporary classical overtones.

This openness to more styles combined with his characteristic of “Sound Innovator” brings him to be a reference point transcending the electric bass as a contemporary composer, despite being contextualized purely in the Jazz world.

Unfortunately, the light of Jaco Pastorius was extinguished too soon, in a tragic way. His rapid rise turned into an equally rapid and brutal descent, a story of mental illness, psychiatric drugs, alcohol, which led him to a sudden isolation from the jazz scene, until the tragic death at the exit of a club at the hands of a bouncer. This career cut short so early did not allow the music world as a whole to enjoy future and possible collaborations, a tragedy that we can compare to that of Jimmy Hendrix on the electric guitar. So there was not the slightest possibility that Jaco Pastorius could not have been physically in contact with the few composers who were experimenting with electric instruments for the first time.

The collaboration between performer and composer is a concept as fundamental as it is banal. Composers rely on performers to discover more and more of the instrument’s potential and performers are often composers themselves. The history of music is quite eloquent in this regard. Let’s think about the figure of Bottesini in the double bass, formidable as a performer and a well refined composer, he brought the double bass to heights never reached before, and from that historical moment more and more composers have dared to compose for the double bass. Nowadays the double bass expresses so many potentialities, from the ordered sounds to the multi phonic, up to use it as a percussion instrument or prepared instrument.

Jaco Pastorius in the Jazz world represents the same importance as Bottesini in Classical Music, and his compositional flexibility makes him easily approachable for the world of Contemporary Music, which is a world full of different currents and schools of thought, some of them very open to modern and Jazz sounds. In addition, his propensity for innovation on the bass creates an aura comparable to the great performers of the past. Unfortunately this process did not happen, and the electric bass is still delegated to a marginal role in contemporary music, totally absent in solo performances.

Jaco Pastorius could have been a link between these two worlds, but for objective temporal impediments, including opposite directions and tragic destiny It did not happen. However, what did not happen in the past can happen in the present and future with a process of research and investigation of the past, which thankfully is recent. For some instruments innovation and the discovery of their value came late, an easily identifiable example in classical music is the discovery of Bach’s suites for solo cello by Felix Mendehlsson, which led to a true renaissance and discovery of the instrument after hundreds of years. In the double bass, the repertoire has had a boost in the twentieth century and in a sudden way bringing the technique of the double bass further and further, and still we see a constant evolution of the instrument.

The purpose of this research is to demonstrate that this process can occur for the electric bass. To achieve this goal, we must be open to collaborations with composers who want to invest the time in discovering our instrument. And composers must be aware that Jaco Pastorius is a cornerstone of the instrument, possessing a vocabulary of expression and potential that can be drawn upon.

Style and Instrumentation

Jaco Pastorius distinguished himself above all others with a particular use of the instrument. He is known for playing a fretless bass for his entire career. Many people think that the first bassist to use the fretless bass in history was Jaco, however Bill Wyman (Rolling Stones’s bassist) had played it before Pastorius came along, using it on their first records in the 1960s, modifying his cheap bass. Also Rick Danko (bassist of The Band) received a number of instruments from the Ampeg company, including the AMUB-1, the first fretless bass model in the market . But during this time it was not so common to use the fretless bass because it was really difficult to play in tune. Jaco Pastorius bought a '62 Fender Jazz Bass already without frets. He declared:

“Looked like somebody had taken a hatchet to it, so I had to fix it up”.

So He painted glossy epoxy over the fretless fingerboard givin it a smooth feel. From that point He played in live and in studio with the fretless. He describes the difference his choice to play Bass Guitar instead The Double Bass in a pretty direct way :

" It’s a pain in the ass. It’s just too much work for too little sound. I love to play with the drummers, and it’s next to impossible to play upright bass with a drummer. No matter how loud get you’re not loud enough"[9]

Anyway, the fretless became an iconic instrument permanently connected to his figure. This instrument has a sound that is very reminiscent of the double bass, because It forces the performer to look for the perfect intonation that is made unstable by the lack of frets. In order to get the best intonation, the note is pressed exactly on the fret, or better, in the position where the fret should be. This requires a meticulous study and a different approach compared to the bass with frets, where to get the right pitch you just have to push the string between the two frets. Jaco Pastorius had developed the technique further on the electric bass through this instrument. In a famous anecdote about his recruitment by Joe Zawinul and his band The Weather Report: he sent an audiocassette with recordings of standards including the famous Donna Lee. Joe Zawinul traded the bass for a double bass at that moment to the reluctance of his famous fusion band The Weather Report:

“Hey kid, do you play bass guitar,too?" he got such a warm, rich sound on that Fender Fretless, I thought He was playing an upright bass”. [10]

In order to reach his iconic sound, he used to play a passive fretless fender jazz electric bass, using only the pick up at the bridge and excluding the one at the neck. In this way the sound was more penetrating, with a clearer attack, obtaining an extremely bright sound when playing the harmonics. His obsession with a deep and present sound that went well with the drums is also defined by his choice of a particular amplifier. In fact he used to play with the Acoustic 360 Amp, with an 18-inch cone that allowed him to play a low E without any distortion or compression of the sound. [11]

His style and his vision of the electric bass was crucial for future generations. He pushed the boundaries far beyond the expectations and the level reached by electric bassists in those years. An important testimony which makes clear the impact, especially in teaching, comes from Neil Stubenhaus, professor at Berklee in Boston in the year of Jaco’s first record was released :

" When Jaco’s record came out, I got an influx of electric bass student at Berklee, suddenly I had all these kids in my class and we’re dissecting Jaco’s first record. “

He continues: " That record was absolutely an institution unto itself. It gave me so much more to teach, and It also gave students hope that the electric bass did indeed have a lot of depth and a lot of ground to cover that had never been touched before." [12]

Portrait of Tracy

The song that I personally chose to identify Jaco’s innovative soul is “Portrait of Tracy”, a piece dedicated to his wife Tracy Lee. Considering his strong virtuosity demonstrated at every juncture, both in the studio, live and in life, it was very complicated to represent the innovative spirit of Jaco choosing only one song. His playing has influenced not only a generation of bass players but irrevocably entire musical genres, blues, funky and obviously jazz. His passion that led to meticulous study of some classical composers (in particular his love for Bach and Hindemith) led him to compose pieces like “Chromatic Fantasy (Fugue in D minor)”.

Why Portrait Of Tracy?

We are dealing with a piece for electric bass solo, where the electric bass is very clearly removed from the role of an instrument of accompaniment only, and carves out a space of its own in which it must hold harmony and melody at the same time.This approach, both technically and compositionally, is impossible on the double bass and until then also for the world of the electric bass. How did Jaco manage to be a “factotum”? With a simultaneous use of harmonics and bass played in an ordinary way, with an extreme ability to make several harmonics resonate at the same time without interference, an extreme ability to extend his articulations in order to create artificial harmonics that until now were inaudible on the bass. Regarding the playing of the right hand we can refer to a technique that concerns the world of classical guitar. Obviously the sonority is different, for the lack of a “nailed” sound, for the size of the strings but above all because they are very different instruments. In fact he often uses his thumb to play the bass line and index and middle finger to make the harmonics resonate simultaneously.

The composer and at the same time interpreter manages to obtain a suspended, ethereal, lyrical result.

To the listener’s ear it is difficult to identify the musical context. If we did not know it was Jaco Pastorius, we probably could not configure it to belong to a Jazz world. Here we are dealing with a piece out of time and context, the absence of drums gives a lot of freedom in the portamento of time. When listening to the piece we can notice that even in the conclusion of the phrases a surprising sensitivity typical from that of a classical musician. .

But let’s go into detail:

- Intro and Main theme:

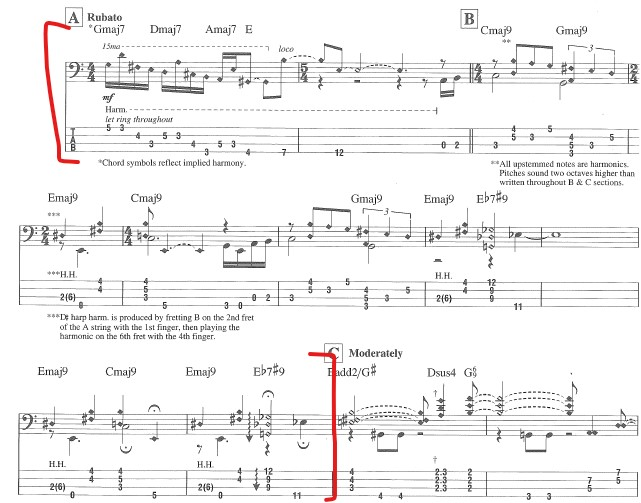

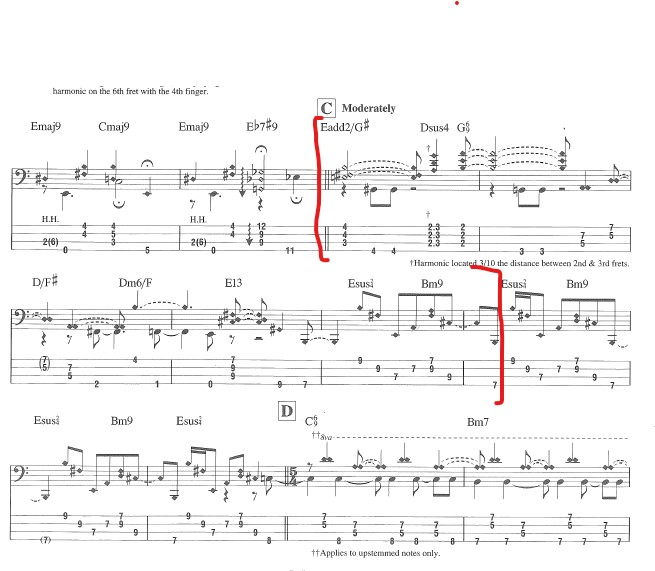

The intro is characterized by this cascade of harmonics that can be easily found on the keyboard of the instrument. The perfect release of the harmonics is achieved by resting your finger on the fret and releasing immediately when you pluck the string with your right hand. The intro follows the following chord progression (Harmonic Progression Gmaj7 Dmaj7 Amaj7 E). In the Main Theme the first two chords are held by the fundamental played normally followed by harmonic triplets leading to a parallel major seventh chord progression, with the major seventh at the strongest point of the melody. He repeats the theme twice, alternating cadences ending first in Cmaj9 and the second time Eb7#9. In measure 4 we have an artificial harmonic D# produced by pressing the second fret (B) with the index finger and playing the harmonic in the sixth fret (D#). On the electric bass this distance can be covered with one hand.

I tried to solve this problem with a technique borrowed from the double bass, playing the harmonic in thumb position, pressing the second fret with my thumb. I’ve found that it can be a good compromise for those who don’t have huge hands like Jaco.

- Section 1

Here you can absolutely notice the composer’s timbral exploration through use of unusual harmonics. This chromatic descending progression arrives at an E13 chord. Note that the chords Dsus4 and G are produced with harmonics located in the 3/10 between the second and third fret. These harmonics are difficult to emit. This leads to a repeated figure that prolongs the idea of the E7 chord.

- 5/4 section

At the 5/4 Jaco creates a repeating ostinato pattern with double stop harmonics in the melody (D and A), and the bass alternates in the notes C-B-Bb , creating a harmonic change (C- Bm7-Bbmaj7). Next, he modulates the same sequence in Ab1313#11 to Gmaj7. Cadence with Bbmaj7- Fmaj7, following the same principle of the bass performed ord. with the melody being entrusted solely to the harmonics.

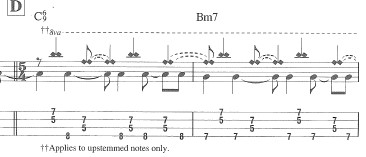

- End of the piece:

The end of the piece consists of the repetition of the initial theme but concludes with a harmony of Emaj7#11. This particular harmony is really difficult to reproduce. Jaco produces this chord with a bridge over the ninth fret on the strings A D G and produces the harmonics with his little finger in the thirteenth fret, simultaneously playing the harmonics with three fingers of his right hand. For the hands of ordinary mortals it is difficult to find a compromise. I tried to reproduce with the same principle of bar 4 in thumb position but it is very complex to play all three strings at the same time. [13]

.

4) New creation

In the previous chapters I compiled some of the missed opportunities from composers and performers in furthering the development of this instrument in contemporary music. The focus of the research has the following question as its core. Can the electric bass be the centre of sound attention? Can it finally be lifted from the foundations of harmony into the spotlight as a solo performer? Can it finally express itself completely following the directives of a composer who is not only looking for low frequencies?

In order to answer the question of the research I decided to collaborate with a composer, Maurizio Tedde, who graduated last year at the Royal Conservatory of The Hague. “l’Autodidatta”, which lasts 7 minutes, and will be part of a suite of 15 minutes in total. The piece is composed for electric bass and electronics, with a strong chamber music synergy of both components.

I consider this work important for the collaborative aspect between composer and performer. In the first part of the research, we highlighted how the lack of collaboration between “the electric bassist” and “the composer” influenced the lack of development of the instrument in the repertoire. Now finally this collaboration takes place, giving the composers a new means of expressing his musical sensibility. I consider this as a starting point to create a process for the electric bass that is more commonly found with traditional instruments and to invite future composers to become more and more interested and comfortable to approach the electric bass.

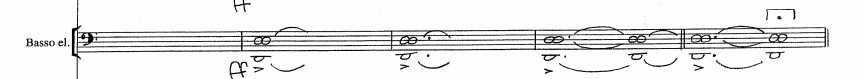

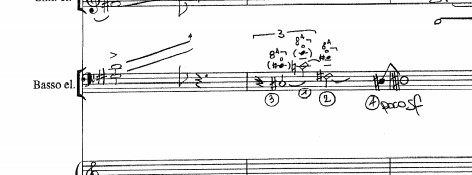

4.1)The Piece

- Bass Part

Although the soloist is the only human presence on stage, the piece comes across as a true chamber music piece. As the composer explains in the opening notes: “The hybridisation between bass and electronics passes through a listening experience. The bass guitar should be played with the electronics rather than upon the electronics. All the long sequences of grace notes cannot prescind from a listening attitude towards the electronics.” The bass part is written not with the normal pentagram but with the use of the tabs, a peculiar choice that will be explained in the chapter dedicated to the composer’s point of view.

- Electronic Part

The electronics were produced analogically in the studio Stockhausen with synthesisers and oscillators. Through these systems he found a way to “play” the electronics,giving them a human touch, with the aim of finding a sound that best suited the quality of the electric bass. Each part of the electronics were calibrated to match a certain type of sound produced by the bass. Maurizio produced hours of music and in retrospect selected only the moments that were, for him, the most suitable for the piece. After the selection Maurizio then worked with Logic and slightly modified in post production some sounds of the electronics (Reverb, Fade etc.).

The bassist will play with the electronics rather than upon the electronics, each musical intervention of the bassist will be extremely connected in both its gestural and sonic aspects. In fact the bass and the electronics will merge, and in some cases will be extremely difficult to recognize which sound is produced by the bass and which is produced by the electronics . Every sound that the bass will reproduce will have a sonic consequence on the electronics, the attack of the bass will recall a resonance of the electronics.

Here it is the videorecording of the piece:

4.2) The performers point of view

I approached the piece as if it were a chamber music piece, like approaching a musical dialogue but in a solitary way. As I listened and played the piece, I found that my technical bass abilities were not emphasized (it is not about playing an extremely rich piece of scales and arpeggios as if it were a Pastorius piece). The difficulty lies in the listening, in the immersion. In fact, the performer is obliged to establish a dialogue with the electronics, to merge with it, transforming something that may seem cold, robotic or inhuman into something rich, warm, communicative, able to instill and arouse emotions.

How to establish this relationship?

First of all by respecting the score but also by listening to one’s own sensitivity through the electronics. From there, a search for sonority and timbre delicacy begins, which hides many facets even in the execution of a simple harmonic, enriched by an expressive gesture that is decisive. The total immersion in this dialogue between two different worlds leads to a difficulty in maintaining a high level of tension in the listening but also in the performance, which can be ruined by a lack of skill or listlessness in the emission of the harmonics, or by the passivity of a beating gesture. Every single gesture may seem casual, but it becomes active and alive only through continuous listening and a continuous search for dialogue with the electronics.

4.3) The composer’s point of view

Interview with the composer, Maurizio Tedde.

L’autodidatta". With this title, you seem to want to express almost a longed-for freedom of the performer with respect to conceptual schemes imposed by the “Academy”. I also know that your musical experience started with the electric bass. Did you think of this piece more as a bass player or from a detached composer’s perspective?

I cannot say that I conceived the piece in clear polemic with the “Academy”, also because it would be a rather old polemic; the fight against the academy has become, in my opinion, the academy itself. Instead, with ‘Autodidatta’ I was trying to express a need for direct contact with the musical material and the instrument; an emotional bond with the music being played. I’m always interested in that kind of sensitivity that goes beyond technique. And then let’s say that the bass, like the guitar, is one of those instruments for which being self-taught is socially accepted, its history is already out of the “Academy”. The bass players we consider professionals are largely self-taught when you think about it. I started playing the bass guitar as an autodidact and I have continued to play it with this approach for all my life; so it is an autobiographical reference, also because I found myself approaching electronics in exactly the same way. The title, then, at least on an imaginary level, is a reference to the character of the autodidact in Sartre’s book “Nausea”.

Did you think more of this piece as a bass player or from a detached composer’s perspective?

I don’t really know how to answer that question, in the sense that I don’t think that distinction exists in my head. I always think of interpretation as a creative, compositional activity, and vice versa. It is a semantic distinction and not one of content. It’s probably no coincidence that I immediately felt the need to also be the interpreter of the piece. In the end, therefore, I did not think of it either as a bass player or as a composer, and indeed I believe that such a clear distinction could have caricatured implications. The intention was rather to create a synthesis between the two polarities, a single entity, and I think this is visible in the creative space that the performer has in this piece.

Does the choice of tabs in your writing allude to the figure of the self-taught musician who does not want to fit into an academic context?

The choice of tablature is certainly linked to the figure of the self-taught, but not only. I, for example, have always used tablature to play bass guitar even though I could read music; I found it had a more immediate relationship with the music I was playing, and it also allowed me to communicate more effectively with the other members of the band. So this is certainly important, but perhaps part of a wider reflection on notation. My intention was to create a link between two worlds that in my mind are extremely close: the world of Early music and the world of Pop music. In both, notation is very open to the interpreter, and in a certain sense interpretation is also and above all invention. The Chamber music attitude, which in my opinion unites these two realities, is a central aspect of the piece I wanted to write. I was interested in looking for that level of interaction that goes beyond what is written, that exquisitely musical level that is impossible to explain in words and that can only be built up by playing together. In the Autodidatta this chamber relationship is the unwritten semantic plane that links bass and electronics. The notation thus unites two conceptual and historical extremes that are dear to me, and lays the groundwork for the bassist’s interaction with the electronics.

Can you describe to me the compositional process of the electronic part? Did you think about the electronics from a bassist’s point of view?

I’ve never written a piece with electronics before, probably because creating sounds on the computer has never been a creative prompt for me. I’ve always needed a contact with the instrument that goes beyond the composition itself, a bond of affection. In writing L’autodidatta I therefore had to try to construct a way of composing electronics that was compatible with the music I wanted to write; I needed to “play” the electronics. Synths and analogue machines allowed me to fill the emotional void that had always kept me away from electronic sounds, precisely because I could play them, I could feel them with my fingers, I could fall in love with their idiosyncrasies, I could make the sound my own on a deeper musical level for me. In writing the piece, I therefore started from the electronics and not from the bass; for me, the bass was above all an idea of timbre, of sound, which guided me during the recording of the electronic sounds. The actual composition took place for the most part directly on the daw sequencer (logic), working afterwards on the recordings I had made in the studio. In this phase the electronic part was formed together with the bass part; I didn’t think of two distinct electronic/bass layers, I thought of them as musically interconnected.

How should the performer approach this piece? How should he relate to the electronics?

I would like my piece to stop being mine the moment someone decides to play it. Let me explain: the idea of interpretation for me is pervasive and comes close, if you like, to the concept of cover as we know it in pop music. My idea of the piece is testified by the recording I made of it, so I am not interested in seeing this idea repeated endlessly; I am interested instead in the interpreter giving his own interpretation of the piece, making it his own. For me, taking possession of a piece means first of all creating an emotional relationship with it, imagining something, filtering it through one’s own sensitivity. The relationship with electronics is always a sensitive one. It is not a solo piece conceptually, the electronics must be listened to in order to build a bond with it, rethinking one’s interpretation from all points of view and especially from the point of view of sound. Electronics is not a background, or a musical layer, electronics is not the second instrument of a duo. It is a solo piece in the sense that the bass and the electronics are not separate instruments. I had a unique sound in mind, with the bass as hybridised as possible with the electronics. A mimesis. So conceptually not a bass + electronics piece, or vice versa. If I had to advise an approach to the piece, I would say that the attitude should be that of Chamber music or a Band, not a solo recital.

Why are you one of the very few (maybe the only one) who has decided to use this instrument as a soloist?

I had never thought of it in those terms, perhaps the most plausible explanation is that they were all wiser than me! Anyway, I did not approach this piece with the prospect of creating a repertoire. Often in Contemporary music, someone who plays an instrument that does not have much space in the literature, commissions the piece from a composer with the intention of creating something new for his instrument, a new perspective. And I’m not against this approach, but in this specific case it didn’t happen that way, the explanation is probably more modest: I picked up the bass (I hadn’t played it for years) while working on the electronics, and I didn’t feel the need to add anything else. That’s all. Also, I could never have written a solo bass piece for the sake of solism. I often only listen to the first and last minute of The Doors’ ‘Light My Fire’, I’m a bit allergic to soloism and virtuosity. It’s a typically non-solo instrument that’s a soloist, yes, but soloism doesn’t necessarily carry with it a certain approach to music. I also didn’t want to recontextualise the bass historically, much less “digest” pop in a contemporary key. The choice of the bass as a solo instrument is a musical choice.

Did you have objective difficulties in finding the expressive potential of this instrument?

My intention was not to create a catalogue of the Electric Bass until its potential was depleted. Let me explain: my goal was never to explore everything that was possible with the instrument, or everything that could put the bass in a different historical light. I was interested in finding my own way of seeing the bass, the way I would like to hear it played. So I don’t think there was any resistance of the instrument or any real intention of mine to destroy it or enrich it as such. I think the piece is just one of the possible expressive potentials.

Were you inspired by any bass players for this piece? And in what way?

I can’t say if I was inspired by anyone directly for this piece, probably not, but I want to believe I was inspired by Paul Mccartney of all people, then John Cale of the Velvet Underground, Carol Kaye in Pet Sounds, Tony Visconti. But who is not inspired by Paul McCartney? In general I like bass players who have a strong sonic identity in the song, who are inside the song. Like Ringo Star with the drums.

Do you think the bass guitar will find more opportunities to express itself solo in contemporary music in the future?

I don’t see why it should not but, again, maybe I can’t see what is obvious to others. I’d like to hear some bass pieces, yes, in fact I’m planning to write more, laziness permitting. It would be nice to treat the electric bass more and more as a normal thing, since it has been a ubiquitous instrument in concerts and recordings for the last 60 years, and less and less as an exotic object from a faraway land.

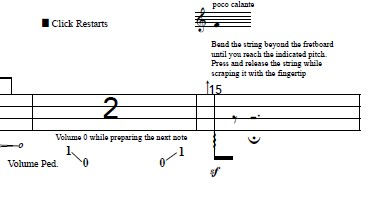

4.4) Details and Moments

In this chapter I want to explain in detail some salient moments and some particular techniques that the performer encounters in the execution of the piece:

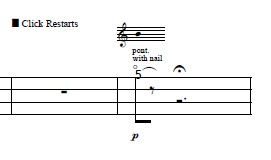

- Harmonics

In the piece, harmonics are easy to identify. In fact, there are no artificial harmonics of any kind. The real difference can be seen in the way harmonics are played. In fact, we can play harmonics in a normal way, as in measure 10 or 14.

Or in bar 8 where the composer requests to play the harmonic at the bridge by scratching with the fingertips, with a dry movement, creating a harmonic with an accent but pp.

At measure 22 the harmonic must be played with the fingernail, creating a p effect.

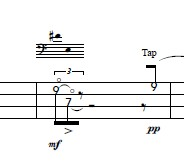

- Tapping

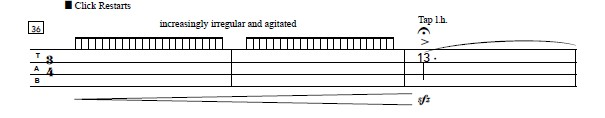

As we found in Romitelli, tapping is a percussive technique used on the fingerboard to search for a specific pitch and color directly from the fingerboard. We can find differences in the various moments in which tapping is used, either as a rhythmic feature within the pulse or as an irregular pattern which is left to the discretion of the performer. We can find a tapping at measure 36, “Increasingly irregular and agitated” tapping. The tapping follows the character and principle with which the performer should approach the piece, always in tune with the electronics.

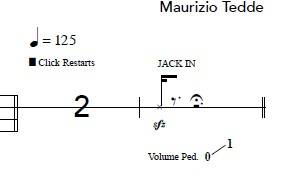

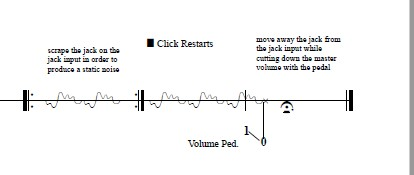

- Jack Cable

Usually the Jack Cable has a simple use, connecting the bass to the amplifier. The composer decides to give it the most important role, the opening and closing of the piece. The first bars of the piece are played with the jack in hand with the bass off, the jack is inserted at bar 4, triggering interference with the electronics and creating a white noise. At the end of the piece (bar 80) the jack is disconnected, the bassist must try to create static noise by making contact between the jack and the input of the jack itself. The noise must be irregular. In the last measure, the jack is removed from its input by lowering the master with the volume pedal, whose function we will analyze in the next paragraph.

- Volume pedal

The volume pedal is used to have control of the master at your foot.

In this way it is possible to insert the Jack with security at bar 4 (pedal at 0—> Jack insertion—> raise the master). You can create a wave effect with the volume of the bass at measure 24 and 25. It is used to not hear the attack of the note (play the note with the pedal at 0 and set it to 1 after the note is played with the right hand, measure 68). At the end of the piece, bring the volume to 0 by moving the Jack away.

- Gestures

The gesture in each playing is a variable that fluctuates depending on the interpretation of the soloist and their performance, which in turn can be influenced by various external and internal factors (personality, daily mood, location, audience, state of health etc.) . Some pieces and their orchestration lead spontaneously to a certain gestural expression, and this is the case of the piece composed by Maurizio.

A striking case can be found at the beginning of the piece, the performer has to play the G# harmonic with the bass off, with the Jack in the hand, the harmonic sounds exactly at the beginning of the electronic part, as if the performer were making a low voice dialogue request, with the bass off, and this request is granted.

However, the gesture does not only play a scenic role and a visual effect for the spectator in the room. Let’s consider the different types of harmonic emission, each particular technique is associated with a specific gesture, which leads to a precise dynamic indication, which is unequivocal in the result. As in the fingertip harmonic, the composer clearly wants a __(pp) dynamic, and with the fingertip it is impossible to go beyond that dynamic range. With the harmonic nail, on the other hand, there is a dynamic piano. In summary, the difference in gestures, even within the same technique, are crucial in obtaining a different timbre, sound and precise dynamic variations, even as subtle as it may be between piano and pianissimo. The fact that we can aspire to this meticulous exploration of timbre on the electric bass, which so far only belonged to the eyes and ears of a public accustomed to traditional acoustic instruments, makes it seem possible to follow many innovative and extremely interesting paths, both interpretatively and compositionally.

Chamber Music feeling,how?

With the simple use of click tracks. In fact, every one or two beats before each intervention of the electric bass, the metronome comes into action, thus helping the performer to relate to the electronics. The click track does not provide a perpetual guide to the musician, but only helps him in these interventions, giving him a wide margin of freedom and interpretation during the piece.

5) Conclusions

5.1) Feedback from the audience

In order to demonstrate the effectiveness of the piece, the idea is to give a live performance and ask the audience a series of very simple questions about the sincere feelings they had while listening to the piece, what motivated their choices and two questions about the figure of the electric bass in this repertoire. Obviously due the very difficult time we are experiencing with the global pandemic, any chance of a live performance of the piece both inside and outside the school before March 2021 has been cut off. So I came up with the idea of recording the piece in the studio and letting a telematic audience watch the video. I tried to simulate an audience as varied as possible: string players, classical guitarists, double bass players, wind players, pop bass players, composers,and even people outside the music world (literature professor, PhD students, dentists, neuroscientists). All united by a love of music and driven by a curiosity to hear something new. I’m convinced that the music has a totally different impact in a live performance compared to watching a video but at the same time this feedback is the result of careful listening, and therefore reliable. In the future I will have the opportunity to perform the piece live, and I will have even more opportunities to get objective feedback from future audiences.

Questionnaire

Which word describes the mood you felt while listening to the piece?

-

Surprise

-

Curiosity

-

Amazement

-

Discomfort

-

Confusion

-

Boredom

-

…

In the first question I wanted to focus on the listener’s first sensation to the sound experience. Identifying genuine feelings in a simple way. I proposed 6 different words that in some way related to positive or negative feelings, with the option of choosing a new word. The most relevant data common to all the feedback I received was the free choice of the word curiosity combined with tension, two people also chose suspension. 3 people instead turned out to be disheartened by the piece in question. 1 person felt the same sensation but with a positive meaning as I will explain in the next point.

Can you briefly explain the reason for your choice?

In the second question I asked for a brief explanation of their choices.

As requested, I received some very short answers and others more articulate.

Many of them justified the tension and suspension because of the composition where silence plays a certain role in the composition. Tension was followed by curiosity as to what the next sound the bass could produce. I quote here a feedback that sums up the concept well: " The piece is well ‘layered’. To get a sense of the texture the recording needs to be played loudly. The extremely high pitches create a kind of melody launched by the short impulses of the bass. The listener is put on hold while the curiosity to what is next is constantly stretched to the max".

As for the term discomfort, this choice is linked to the initial moment when the Jack is inserted into the bass triggering an immediate and dynamically strong reaction of the electronics, abruptly interrupting the previous silence. 1 person chose discomfort with a positive meaning, associating the music with the typical atmospheres evoked by David Lynch’s films. 3 people chose the word curiosity together with discomfort.

I received some feedbacks that I consider very important on a technical level: the first concerns the importance of careful listening with good devices (headphones or speakers) in order to enjoy the details offered by the electronic frequencies to the maximum, the second concerns a sort of lack of a beat (clicktrack) during the track that could somehow enrich the composition. Another aspect that reassures me in the role of electric bassist in this particular context is the engaging performance: in fact apparently it contributed to the tension and curiosity fuelled by the piece. One comment reads as follows: "The visible gesture of the player and not visible one of the electronics and the cause and effect relationship between these two".

What impressed you the most while listening to the piece?

All converge on the unique fusion and combination of bass and electronics, the dynamics and the different sounds and timbres that the bass can produce even using advanced techniques such as jacking at the beginning and end of the piece. Some are impressed by the performance of the performer who manages to occupy the stage with little musical material available.

Pick a number from 1 to 10 (1 being the lowest), how innovative do you consider a solo electric bassist to be in this musical context?

All those interviewed responded positively to the question, with the majority indicating 8 and two people indicating 6.

After listening to this piece, would you like to hear more electric bass pieces in the future?

Everyone thinks that this instrument has potential in the future.

5.2) Conclusions