Integration and development of jazz drum soloing

Borut Rampih

Student number: 3265447

Research supervisor: Jarmo Hoogendijk

Teachers: Eric Ineke, Felix Schlarmann, Stefan Kruger

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my teachers, Eric Ineke, Felix Schlarmann, and Stefan Kruger, as well as my research supervisor Jarmo Hoogendijk for their help, patience, insight, knowledge, and inspiration.

Last but not least, I would like to thank my family and my girlfriend. Without you, all of this would not be possible. Thank you from the heart!

Preface

When applying to study at the Royal Conservatory’s master of music program, I was faced with a tough choice – What to base my research on. Music is an incredibly vast field of many different areas of interest, from the ones about music as a skill (Theory and harmony, technique, ear-training, musicality, arranging… ), to psychology ( the art of performing, practicing techniques and methods, methods of coping with anxiety and stress, memory…), to the business side of music ( networking, recording and selling your product, making yourself into a brand, copyright laws, organization…). To make a choice, I had to look at what attracted and captivated me the most in music and what drove me to persevere in studying it all these years.

Ever since I became interested in music, I was fascinated with performers’ energy, emotion, and abilities to unite with one another in creating it. After learning more and discovering jazz and improvised music, I became fascinated by the individualistic and personal aspects of music. Usually, with the rest of the band supporting him, an individual would step into the spotlight to play his solo.

What is a solo? A question that may have as many answers as there are people. One definition is that a solo is a musical performance given by one person alone or musical performance in which one person is given special attention (Cambridge Dictionary, n.d.). That may be so, but there is so much more to the act of playing a solo. Often using the harmonic and melodic structure of the piece being performed and also its mood and atmosphere, the artist spontaneously composes his view of the moment as it presents itself to him.

There are innumerous points of view when it comes to soloing. Displaying technical proficiency and theoretical knowledge, expressing your thoughts and emotions, your view of the world and life, social interactions, your hero’s and influences, etc., while telling a story to the audience. Through that story, perhaps even without realizing it, you are exposing yourself as you are, with all your goals, desires, fears, and experiences. . Because of the search for ones-self, individuality while simultaneously sharing the experience with others, the fear, self-consciousness, and anxiety of being put in the spotlight, the freedom of expression, and storytelling, I decided to devote my research to the art of drum soloing.

Drum books are mostly populated with technical and independence exercises, comping ( accompanying another instrument) and interpretation advice, different rhythm patterns, reading charts, etc. However, very little information is available on drum soloing. Usually only mentioned on a few pages per book, the information consists mostly of a handful of more or less useful phrases you might use, a short transcription, and an analysis of it. The usual advice is to copy what you hear and like. Looking at other research papers and articles, they usually focus on one specific drummer and their style, not on general methods of drumming and absorbing other drummer’s language or developing your own. That further motivated me to research drum soloing.

My research question is: “how to integrate the playing of the masters into my own vocabulary and how modern drummers that I admire developed the classic language to fit their own style. I am also interested in finding and developing exercises that would help with technique, confidence, fluidity, creativity, and expression on the drumset.

Methodology

I will go over some of jazz drumming’s most influential figures from the bebop era, analyze their playing and try to find methods and exercises to integrate their playing into my own vocabulary. I will review my thought process with working with this material in the past, try to expand on it, and reflect on the mistakes I have made in my approach. I will also try to find certain phrases and look at how drummers developed them over the years and made them their own.

I will choose a drummer that I like, focusing on solos played with sticks, and transcribe a few of their solos. From each solo, I will choose a couple of phrases they play and try to play my own solo using a variation of those phrases. I will analyze their playing as well as how my playing changes with incorporating their approach.

I will try to present my process mostly by including transcribed material of the solos and exercises and my thoughts, analysis of the thought processes that were used as well as technical or coordination difficulties that I had to overcome to play them. As it is challenging, if not impossible, to represent a person’s touch, feel, sound and articulation only by notes on the paper, I will try and present the transcriptions and exercises by video recording myself playing them.

History

“You should check out the history” – This is probably the most common reply I have heard in regards to the question of how should I begin, approach, and develop my jazz drum soloing both when starting with jazz drumming and also throughout all the years developing my skills.

There are two schools of thought on how one should approach this: Either you look at a modern drummer you like and ask yourself the question of what he listens to and which drummers influenced him the most, or you try to start at the beginning of the art and work your way to the present day. No matter which method you choose, the process usually involves listening to as much music from the chosen drummer as possible so that his style, phrasing, and sound are “in your ear,” as well as transcribing his solos and comping and trying to play them as close to the original as possible and then moving on to another drummer.

This is the process that I was involved in throughout my career, and it seemed to work well until I noticed that I kept asking myself a series of questions all the time. “Why is it that I can play a transcription of a drummer perfectly, but when the times comes for my solo, I feel uncomfortable, without ideas, perceive myself as boring, etc., “Why is it that I seem to forget all the “licks” and phrases learned from a transcription so quickly?”, “How is this going to help me develop my own sound, ideas, and identity?”. Those are only a few of the many questions I started to ask myself regularly.

When I found myself in a musical situation where I could play the transcribed material verbatim (the tempo, feel, form, etc., of the played tune, was similar), it all worked out. The problem was that those moments were rare. More often than not, I found myself in unfamiliar, uncomfortable situations where I could not rely on the similarities of an already transcribed solo to help with improvisation.

“Stealing” phrases

“A plagiarist steals from one person. A true artist steals from everybody.”(Pablo Picasso, n.d.)

During my research, I have clearly noticed how drummers were using literal phrases from one another. It is unclear whether they were acts of paying tribute or homage to a fellow drummer, the fact that they were, of course, heavily influenced by one another, playing in the same genre and collectively developing the language of jazz or all of the above. The fact remains that we can find phrases of the masters played today with minimal or virtually no development.

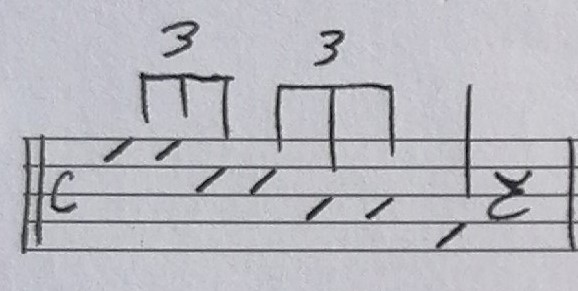

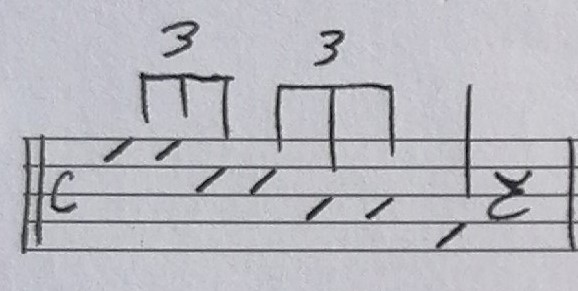

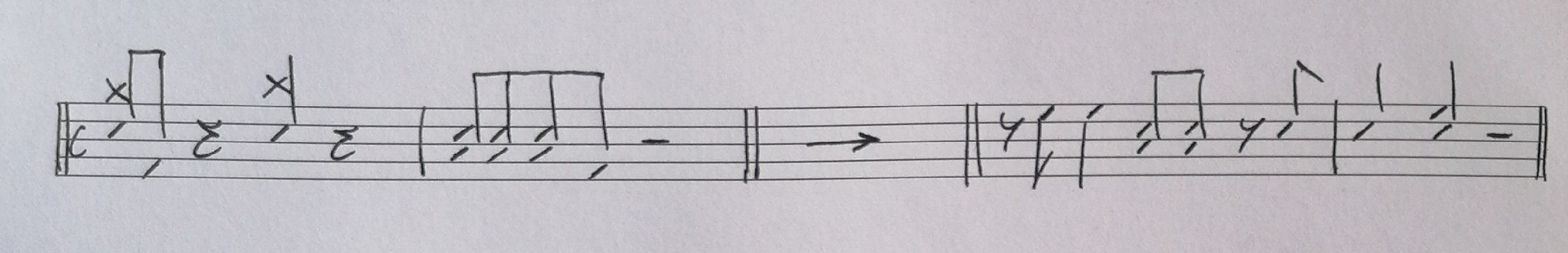

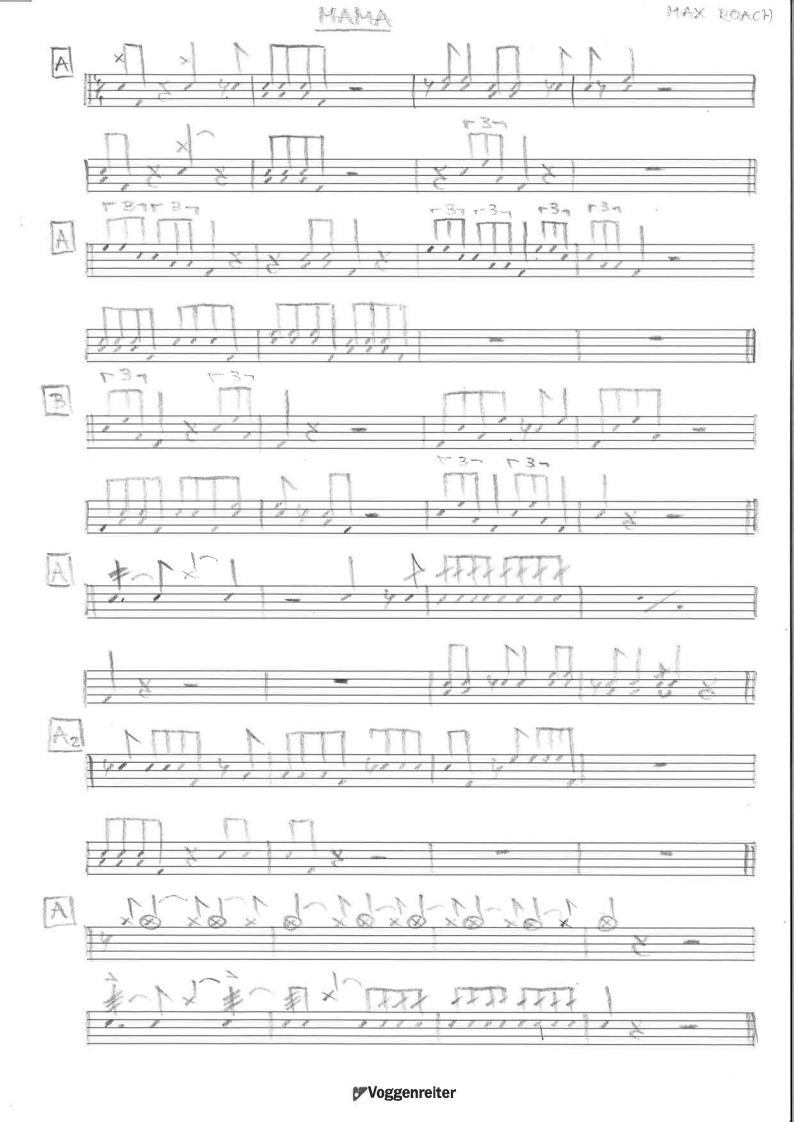

For example, a Max Roach triplet phrase from “Mama”:

played double-time by Ralph Peterson Jr. (Brecker - El Nino, 2007, 09:45)

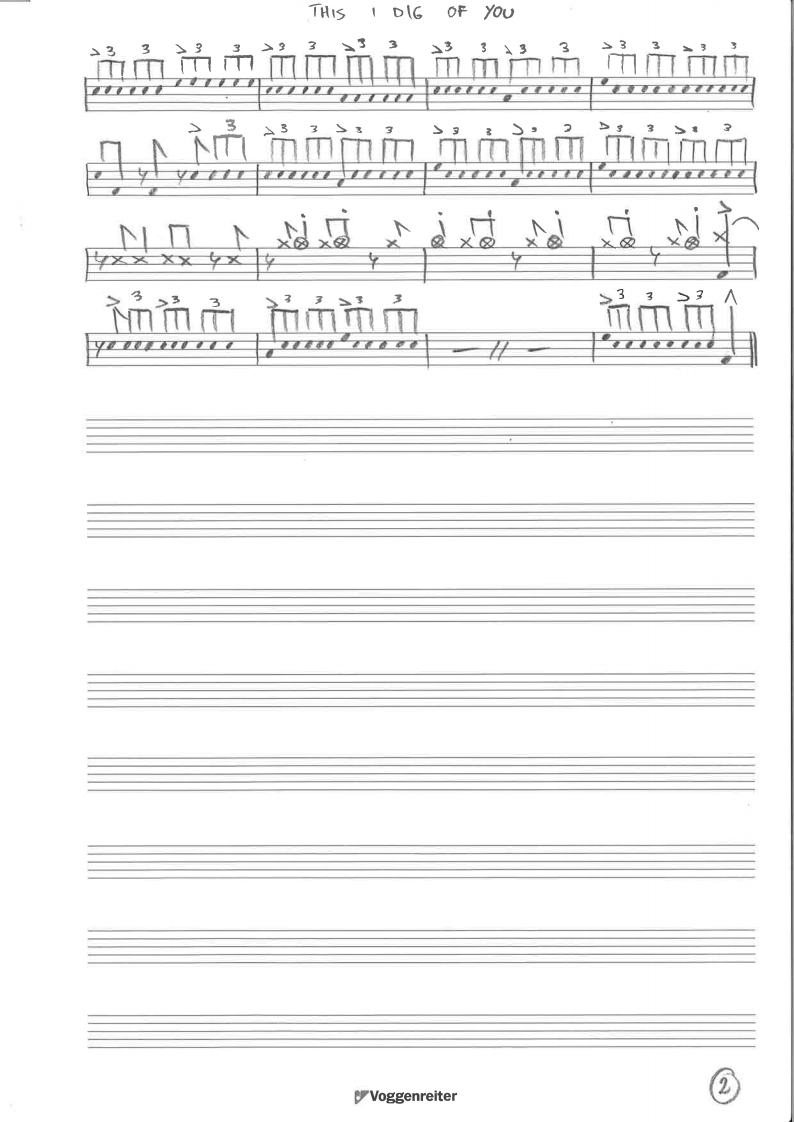

or the hi-hat phrase from the same transcription:

Played a year earlier by Art Blakey from measure 10 of the second page in the transcription “This I dig of you”

“There was no two rappers who rapped the same in the 80’s” (Dogg, 2015, 01:25)

Watching a rap/hip-hop interview, I was reminded of an interesting term called “biting.” The term describes the act of taking someone else’s material and style and deceitfully presenting it as your own. It was against the law in the traditional days of hip-hop, and rappers made a conscious effort not to sound like other artists. (Rhymes, 2016).

“Hip-hop values originality over any other quality; as a rapper, you are nothing if you are not yourself.” (Pigeons, 2016, para. 1).

The idea applies to every music genre and every art form, so it resonated with me, and I started thinking how every drummer I value has his own sound, presence, and expression. Max roach, Art Blakey and Elvin Jones, to name a few, all play the same instrument but make it sound unique and instantly recognizable. When I listen to drummers like Kendrick Scott, Bill Stewart, and Brian Blade, it is clear that this concept does not apply only to historical drummers.

Like Eric Ineke mentioned in the interview, even though you can hear where the phrases come from, the “theft” does not rob you of or define your own identity. Ralph Peterson Jr., in the above example, uses the same phrase as Max Roach has and countless drummers before him (albeit in a slightly different orchestration), but that does not make him Max Roach. The fact further solidified the importance of sound, touch, flow, character, etc., in soloing.

I have lived by the words of the famous drummer Tony Williams. He said that drumming is an evolutionary pattern and that one should first spend a long time doing what other great drummers were doing and not search for their own sound too quickly. (Williams, as cited in Riley & Thress, 1994, p 5). The question – “when will I be ready to start searching for my own style?” arose naturally but was repressed, perhaps using the quote as an excuse, to an undetermined time in the future. While I still believe in the validity of the quote, I think my approach was wrong. I believed that mere copying of what the masters were doing was enough, but now I see that I should have spent more time trying to integrate their vocabulary, concepts, and ideas into my own, and through that eventually develop my own style and sound.

Developing phrases

There are many ways to develop phrases.

- Taking a phrase from a drummer and changing the orchestration

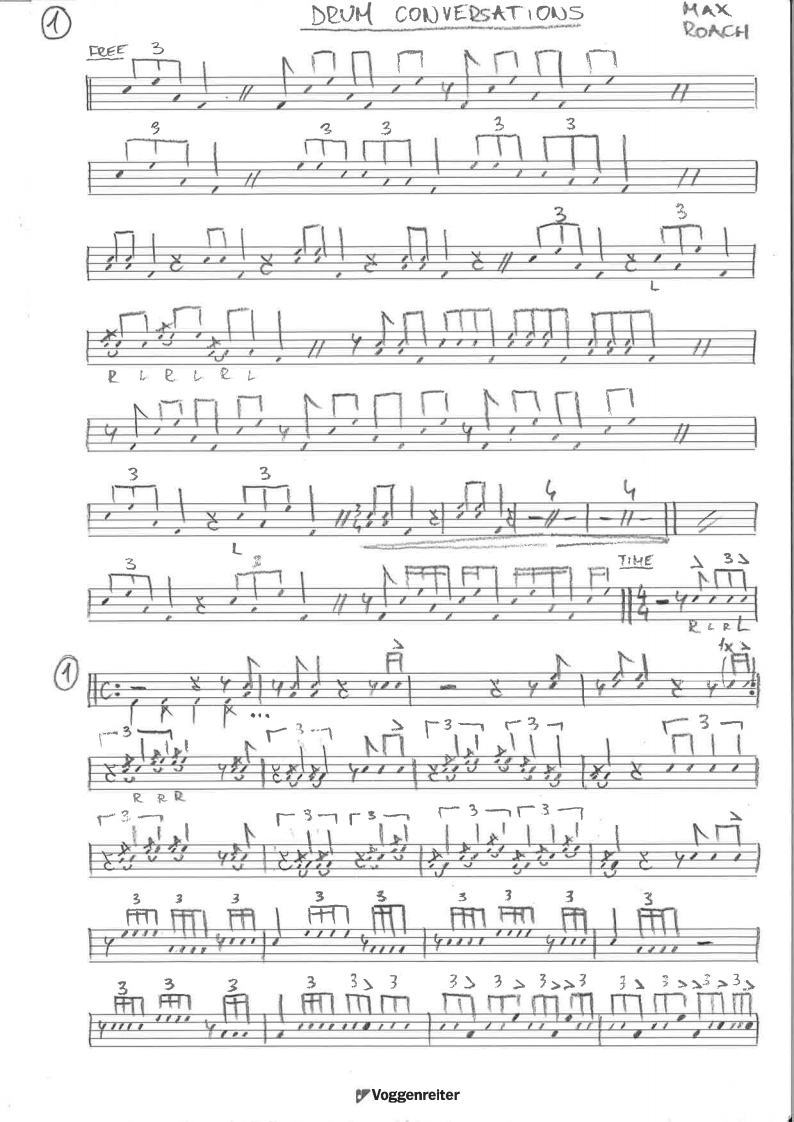

For example, I took a phrase from page five of Max Roach’s Drum Conversation Drumconversation1:

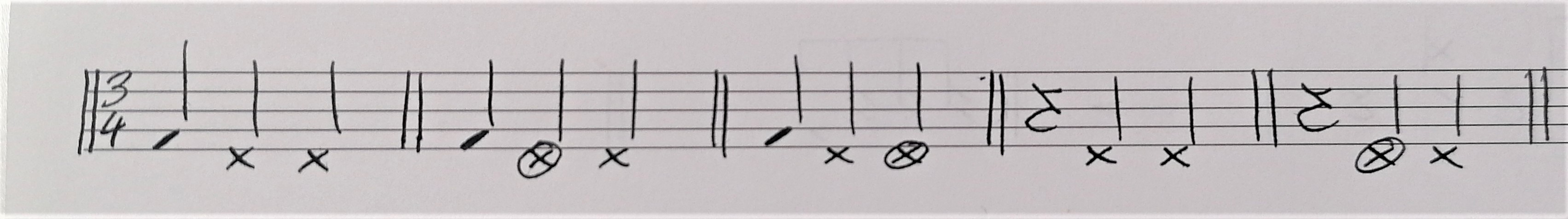

I changed the orchestration first to include cymbal hits combined with the bass drum. Then I changed the last 4 sixteen-notes and moved them to the toms. Then I added the 3/4 hi-hat pattern.

The pattern already seemed more interesting and “modern,” utilizing the whole set and an ostinato hi-hat pattern. I wanted to develop it further and make it more intense, so I took the phrase’s first five notes - made the phrase into a sixteen-note phrase in groups of five with the same ostinato pattern. That changed an ordinary phrase to an over-the-bar phrase.

I then changed the ostinato hi-hat pattern to match the “new” phrase. Next, I orchestrated the right hand to change a drum with every repetition. For the last step, I added accents to every second sixteenth-note of the right hand.

Video: MaxvariationphraseVid

- Changing the rate/adding or removing notes

For example, in the classic Max Roaches phrase from “Mama”:

I decided to change the rate to eight-notes to get a 7-note grouping over-the-bar phrase.

Video: MaxsevenVid

If you wanted a more “normal” resolution, the solution would be to add a bass drum at the end of the phrase (or in the middle!). Similarly, by removing a note, the phrase will become a grouping of 6 eight-notes.

- Using your knowledge of the drummer and the motion

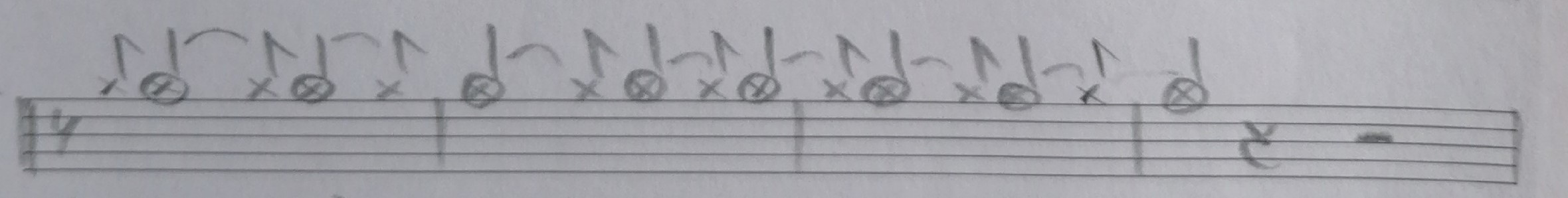

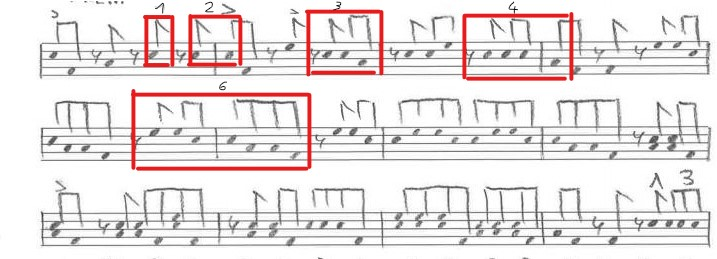

For example, I saw a live video of Gregory Hutchinson, where he played a phrase in the solo of Hide & Seek I wanted to replicate.(Gregory Hutchinson-Hide & Seek(Solo)- Live @ the Jerusalem Theater 3June2009 1080p, 2009, 01:27-01:29)

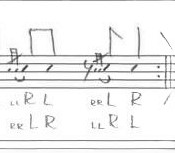

From the transcriptions I made, I knew that Gregory likes to use six-stroke rolls. Listening and watching the solo, I noticed that the motion of the phrase was from the tom to the snare and back, then right, to the floor tom.

I started the phrase on the tom and played a six-stroke roll in triplets, with the accents on the first and last note (Rllrrl). Now I needed to go right, so I played a variation of that phrase from the snare to the tom and floor tom ( Rlrrll).

Since I needed to get back and didn’t like to cross hands awkwardly, I removed the last note (L) and replaced it with a bass drum.

I noticed that my phrase was longer than his, so I needed to shorten it. The first part remained the same; in the second figure, I kept only the notes 3,4 and 5 starting on the floor tom.

Video: HutchvariationVid

Fast: HutchvariationfastVid

I do not presume that my phrase is anything like what Gregory played, yet I believe it has a similar energy and effect. I have also gotten at least two phrases out of it that I can manipulate.

- Using the rudiments

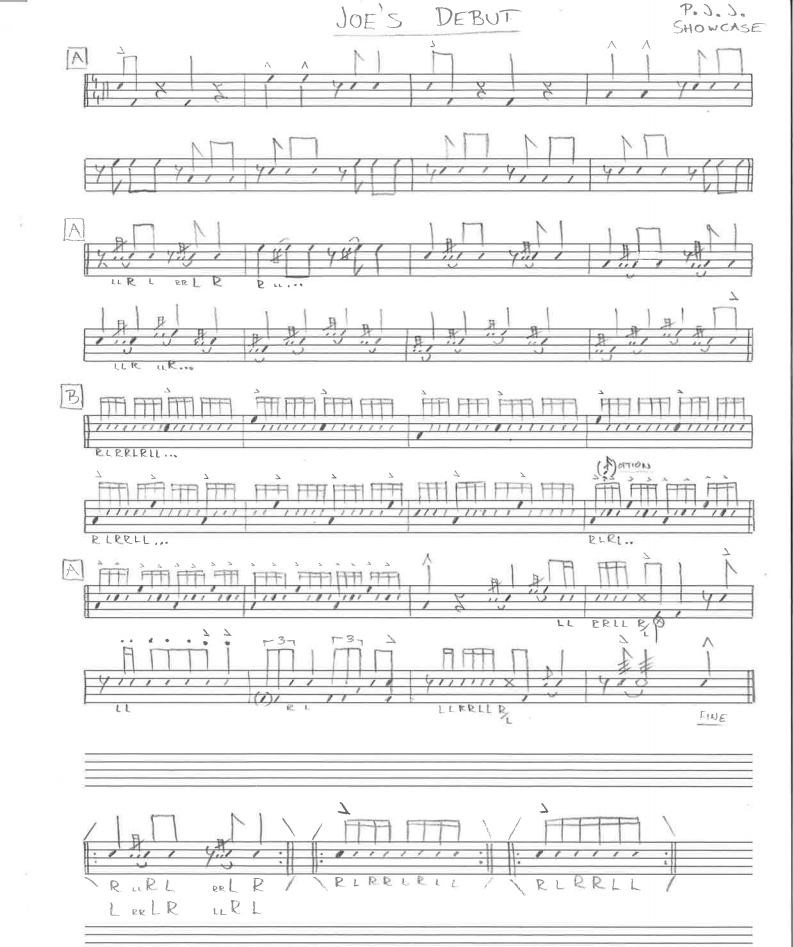

For example, taking the second rudiment in Alan Dawson’s rudimental ritual(Dawson & Ramsay, 1998, pp. 11–23), the single drag, a rudiment often used by Philly Joe Jones (bar 9 of Joesdebut).

We can change the first right hand to a stick-on-stick shot. Changing the second and fourth eight-note to the bass drum gives the rudiment momentum, and the phrase sounds interesting if we orchestrate the second group of eight-notes around the set.

Changing the second half ( eight-notes 3 and 4) of the phrase to triplets around the set, we come to the phrase Gregory Hutchinson played in bars 7 and 8 of Wonderfulwonderful1.

Note on variations and transcriptions

As stated in the methodology section, my original plan was to choose a few phrases that I like the most out of each transcription. With those phrases, I would experiment, change their orchestration, spacing, dynamics, etc. and use them to play a solo.

For example, here i play variations on the solo of “Mama” by Max Roach: MamaVariationsVid

While working with the material, practicing the transcriptions, choosing phrases, and playing variation solos, I kept noticing a couple of things:

-

Through the process of practicing a solo, I found myself (because of technical, coordination, or melody-related difficulties) experimenting with and playing many of the variations naturally.

-

Since I wanted to give every phrase a chance, the process of experimenting with phrases that I didn’t feel connected to became tedious and unproductive. As Eric Ineke explained in the interview, the phrases did not fit my playing.

-

I ran into mostly the same problems that I outlined in the history section (forgetting phrases, thinking in terms of “licks,” lack of sound/idea development…)

Because I was repeating the same process that I have always had with the same drawbacks, I decided to change my methodology.

Reviewing my notes, sourcebooks and looking at all of the transcribed material, I started thinking of what made all these drummers different and what made them similar. I found that I was missing the bigger picture. What was it that made all these drummers unique? It was their sound, their approach to soloing, the concepts they developed, their thought process.

I realized that if I succeeded in memorizing and copying all of their phrases, I would ultimately just be a copy of them, and that was not my end goal.

“Anybody can play. The note is only 20 percent. The attitude of the motherfucker who plays it is 80 percent.”(Miles Davis, n.d.)

Transcriptions definitely have tremendous value. John Riley explains in his book The Jazz Drummer’s Workshop that: “By moving from approximations of another person’s phrases (consisting only of things you could already do) to the actual material (which is often very foreign), you’ll gain a deeper musical sensibility and become more actively involved in accelerating your growth.”(Riley, 2004, p. 30) He also explains that: “The process of transcribing is beneficial on many levels. First, it improves your listening and concentration skills. Second, it provides new vocabulary. And third, transcribing improves your reading and writing skills. Plus, you can manipulate and permutate transcribed material, merging ideas from different sources more easily than things learned by ear.”(Riley, 2004, p. 31). The added benefit, I have found, is that transcribing complete solos gave me a deeper understanding of the drummer’s story “arc” - How the drummers build and develop the emotional high and low points of the solo.

After transcribing a couple of solos, getting over all of the technical challenges, and getting to know the drummer’s language more, I started thinking and experimenting with his thought processes and concepts. Questions like how does he sound, his phrasing, tuning, touch on the instrument, spacing, how often does he repeat certain phrases, what phrases instantly “click” with me, how does he begin and end his solo, his soloing “arc,” how conscious is he of the form/melody, etc., all gave me valuable insight into his playing.

Next, I would improvise solos of my own using his approach, but rather than thinking about what phrases he used, trying to copy whole parts of his solo, etc. I started thinking more in terms of the above questions, and that became the main focus of my development.

Soloing

Kenny Clarke

For the purpose of starting my research, Kenny Clarke was an obvious choice. While not really known for his drum solos, he is one of the great drum innovators and a basis for all the drummers of the bebop style and beyond.

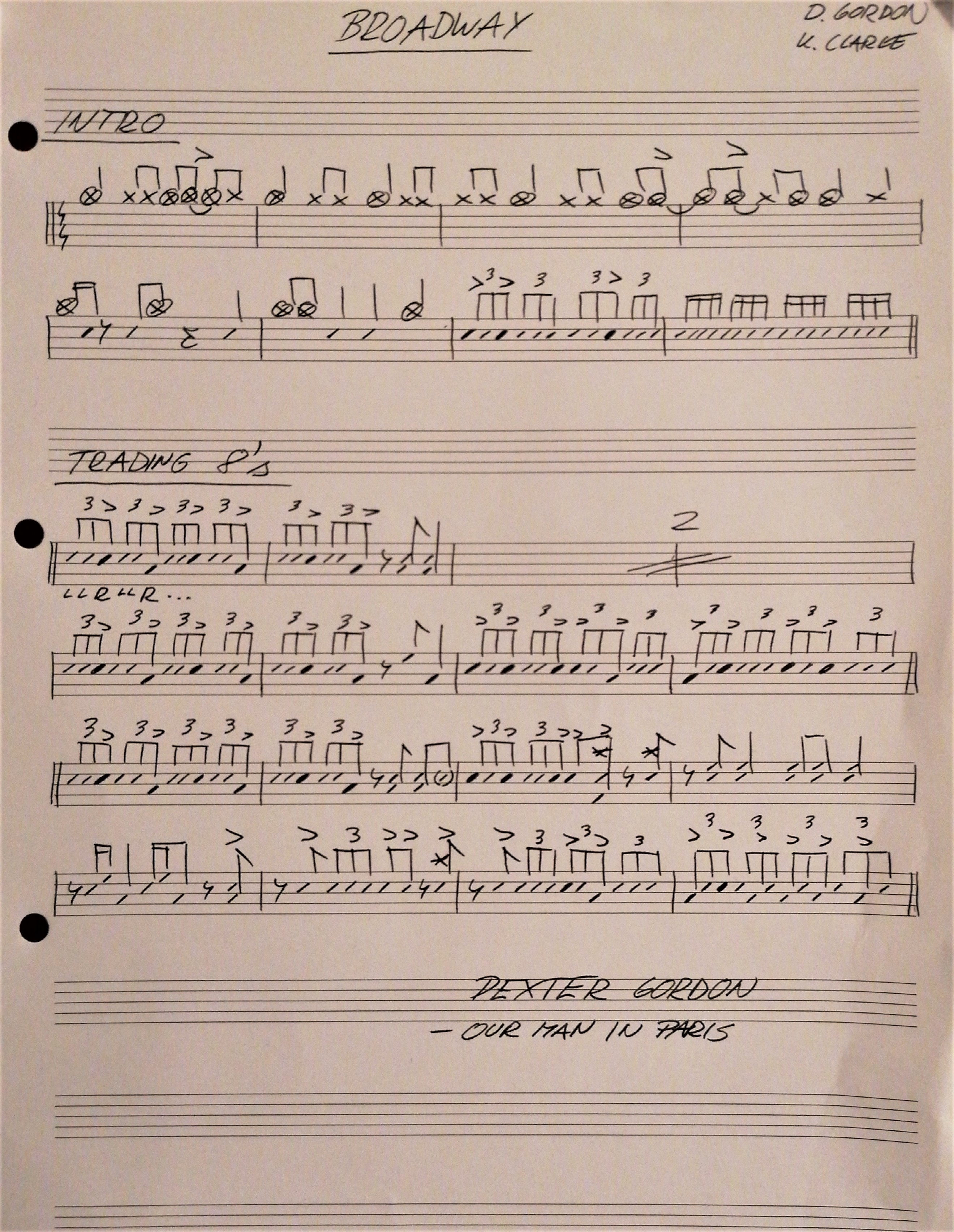

“Broadway” (Gordon, 1963)

- Transcription: Broadway

- Video: BroadwayVid

Analysis:

Kenny opens the tradings with a great question-and-answer phrase. Apart from small changes in the orchestration, the phrase is repeated for almost the whole solo. Both concepts (staples in jazz music in general) are heavily used and developed by Max Roach( see Max Roach).

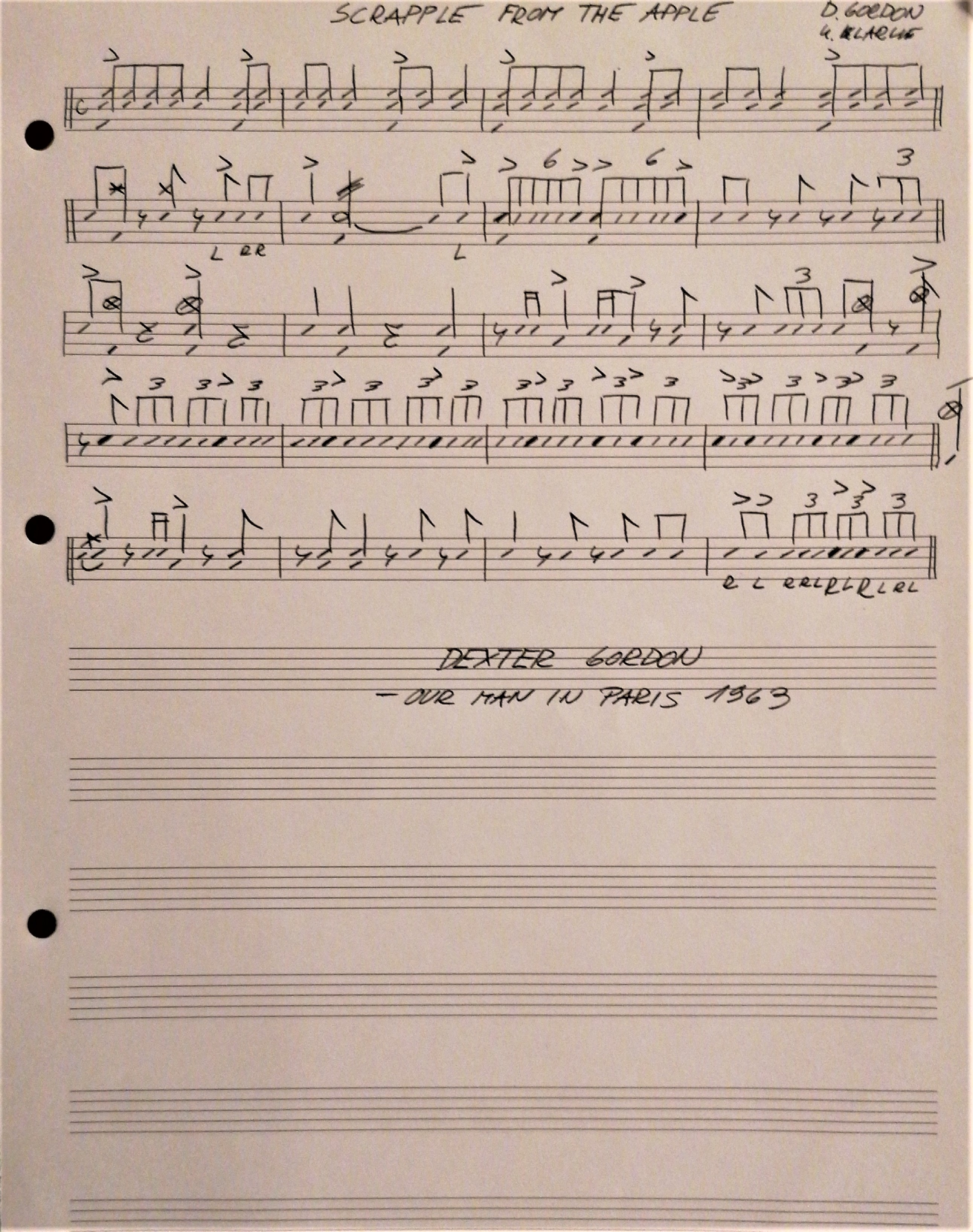

“Scrapple from the apple” (Gordon, 1963)

- Transcription: Scrapple_from_the_apple

- Video:ScrappleVid

Analysis:

In the first trading ( first four bars), Kenny sticks to one idea throughout and supports the accents with the bass drum in unison ( a tool used frequently by Bill Stewart).

In the second trading, bars 2 and 3 ( bars 6 and 7 in the transcription) show apparent use of rudiments, namely the closed and the six-stroke roll. The rudimental concept was developed heavily by Philly Joe Jones, and both the concept and the phrases are used today to great effect by drummers like Kenny Washington and Gregory Hutchinson ( see respective entries).

He opens his solo in the B-section with the famous “Mop Mop” phrase (Coleman Hawkins - Boff Boff (Mop Mop), 1943) - used often to open a solo or as a clear ending of the solo. Bars 5-8 of the B-section (13-16 in the transcription) work as the solo climax before the final trading. Kenny plays a flurry of triplets with various accents, used heavily by Art Blakey, Max Roach, Roy Haynes, among others.

While it was not apparent to me until recently ( as I started practicing playing melodies extensively), it is worth noting that the solo, for the most part, very closely follows the melody.

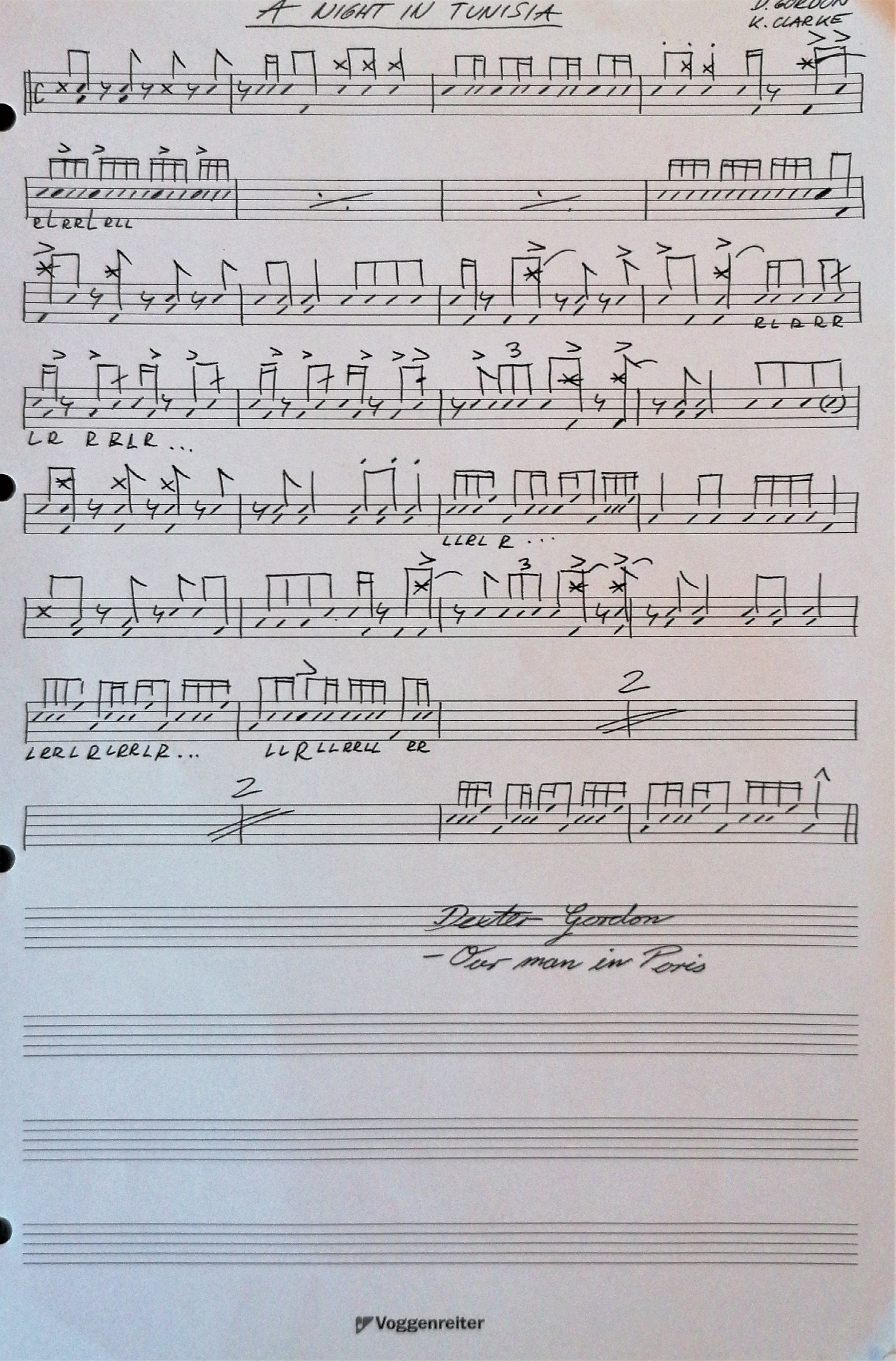

“A night in Tunisia” (Gordon,1963)

- Transcription:Anightintunisia

- Video: AnightintunisiaVid

General thoughts:

It is fascinating to see and hear how Kenny Clarke has influenced virtually every bebop ( and modern!) drummer in one way or another - from general concepts of his playing to his literal phrases. Worth noting is also the fact that he sings out loud every phrase that he plays. He very clearly settles the argument of why we should study history, and it would be fascinating to research who he was influenced by.

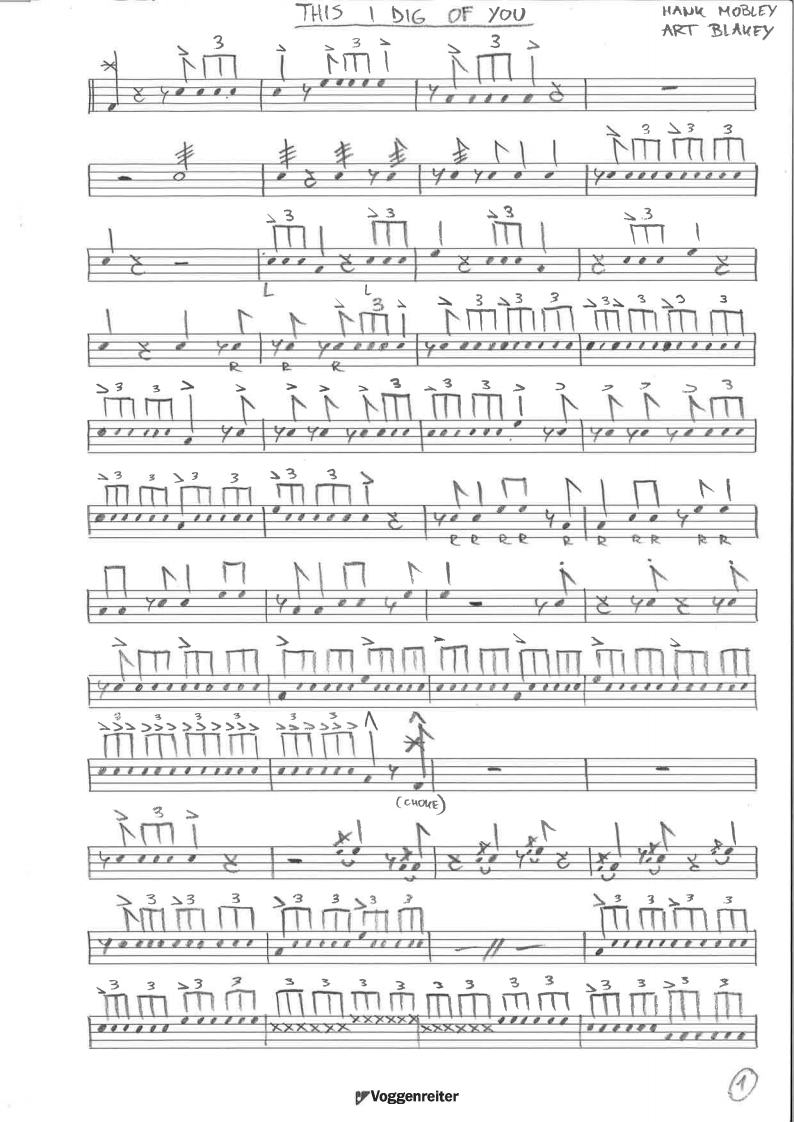

Art Blakey

“This I dig of you” (Mobley, 1960)

Transcription: Thisidigofyou1

Video: ThisidigofyouVid

Analysis:

This classic and deceptively simple solo starts powerfully with a crash and a “3 over 4” phrase around the toms followed by a bar and a half of a break - a very effective tool that captures the listener’s attention. Next, Art plays his signature closed rolls using both hands. After another section of triplet phrases, the solo pics up in energy and sets the tone for almost the whole solo. Worth noting is that until this point ( perhaps throughout the solo), he is “feathering” the bass drum (Playing on all four beats). He is building in intensity and mostly repeating similar combinations of eight notes (that he either plays as a syncopated 3 over 4 phrase or as single eight notes on the off-beats) and triplets. He begins his second chorus with a flurry of rimshots followed by chocking a cymbal as the section’s climax. After the barrage, two whole measures of rest are welcome. He follows with flams organized as quarter-note triplets around the drums (a technique that is heavily used by Max Roach) before once again building a wall of sound with the triplets. To change the texture, he orchestrates one of the sections on the rims of the drums and by going to the hi-hat (again using a phrase that Max Roach often used). The solo is intense from start to finish. The flurry of triplets acting like a carpet of sound, contrasted by the occasional silence ( similar to the triplet roll between the toms and the bass drum that Elvin Jones regularly played with a similar effect (Jones, 1978).

While not technically very difficult, the speed and the sheer intensity in his playing made it challenging and helped my single-strokes.

Concepts:

-

Committing to a phrase, repeating and building it, playing the same phrase with a different texture to surprise the listener.

-

Using rests as contrast

-

Creating a “carpet” of sound

Max Roach

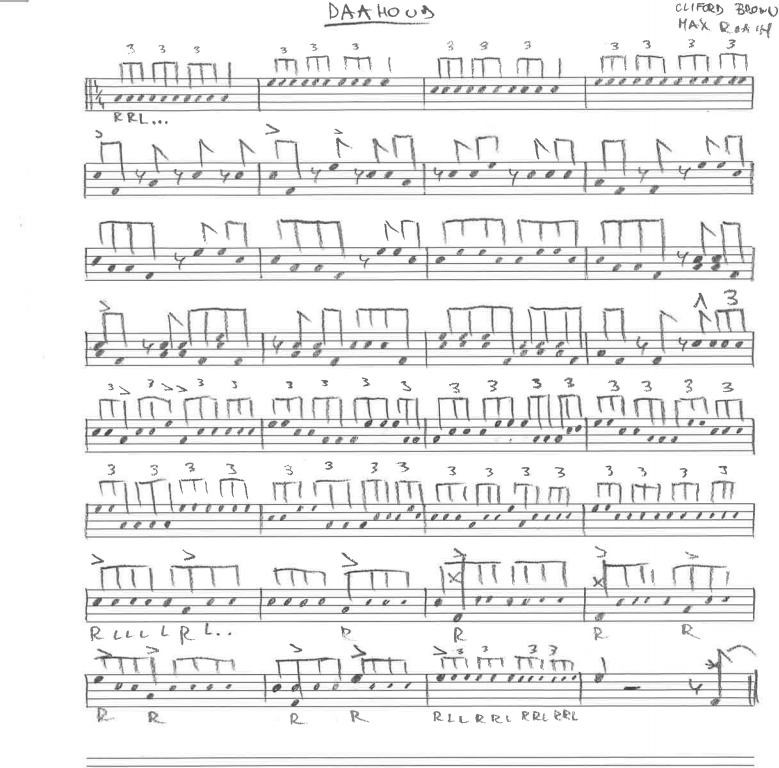

“Mama” (Roach, 1961)

Transcription: Mama1 , Mama2

Video: MamaVid

Variations: MamaVariationsVid

Analysis:

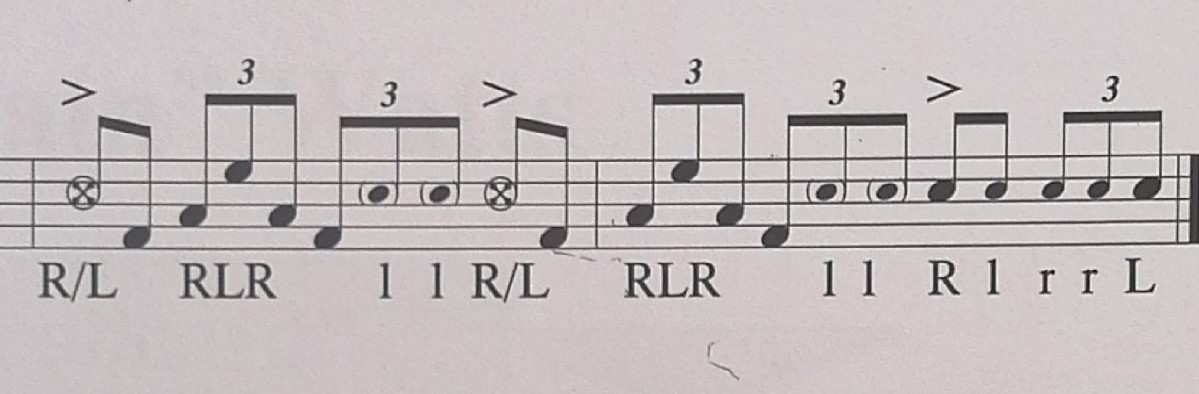

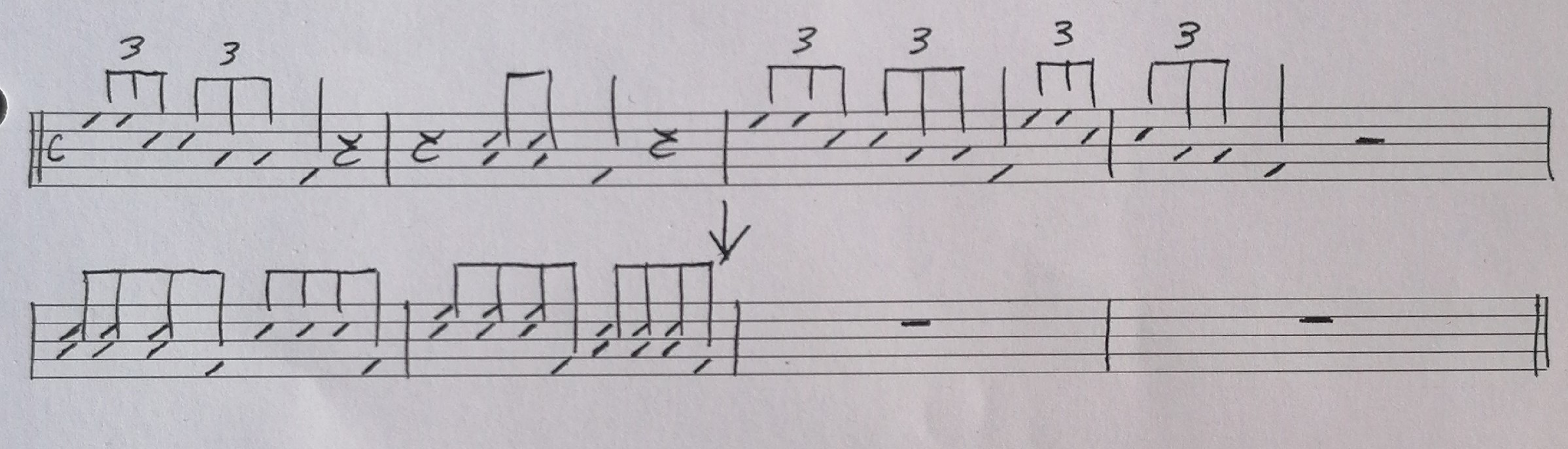

Max begins his solo over a walking bass line with a question-and-answer phrase. It is amazing how clear and multi-faceted his realization of the concept is.

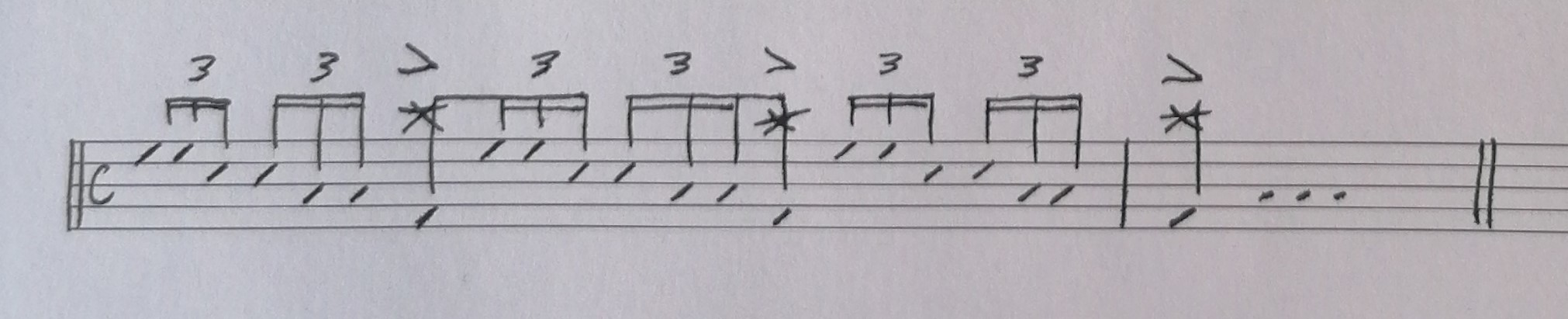

For example, we can look at this concept as a one bar question-and-answer:

Question and answer as a two-bar phrase:

As a four-bar phrase:

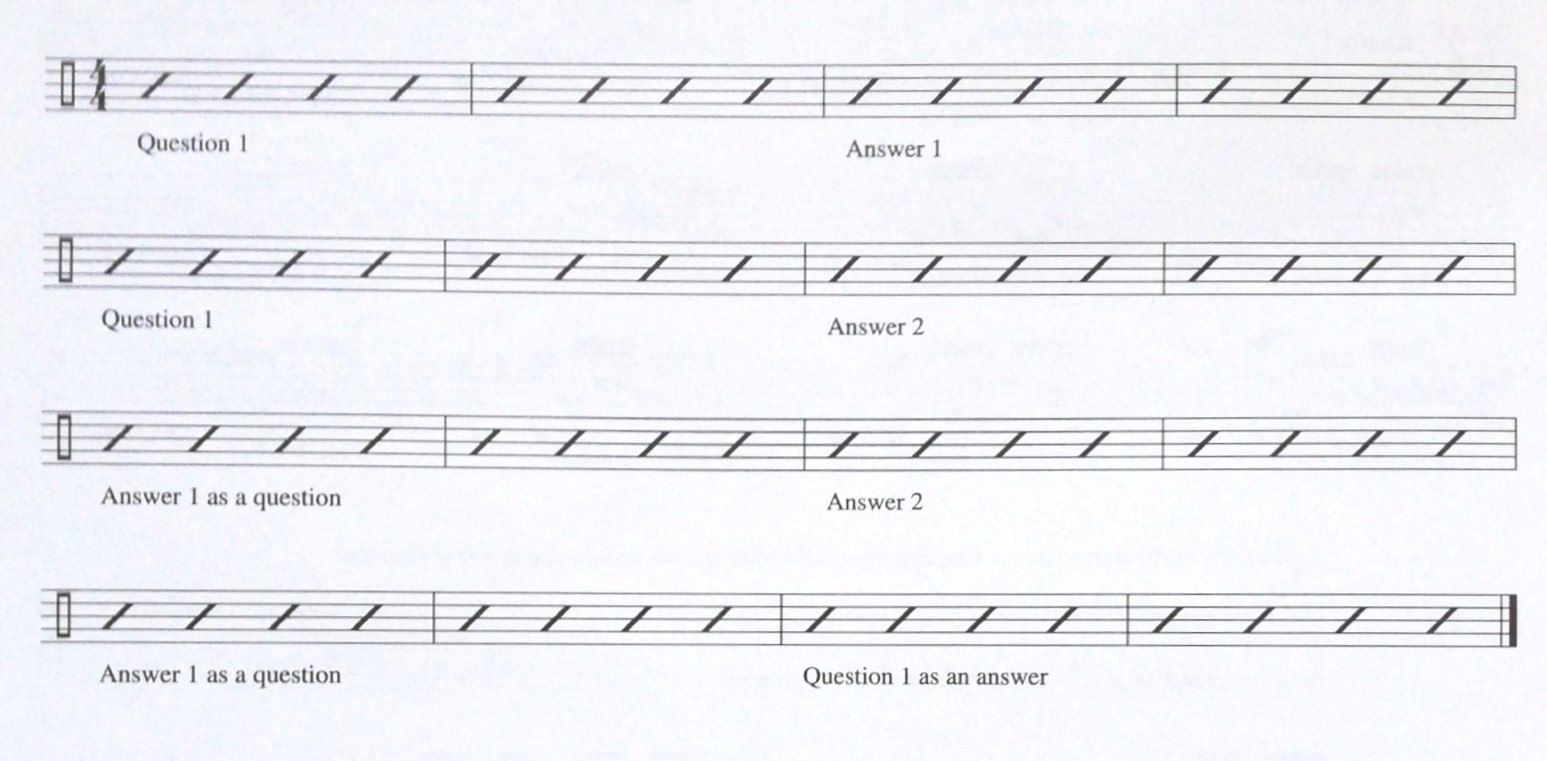

John Riley provides a great framework as well as phrases for developing question-and-answer ideas:

Experimenting with the question-and-answer approach: QuestionandanswerVid

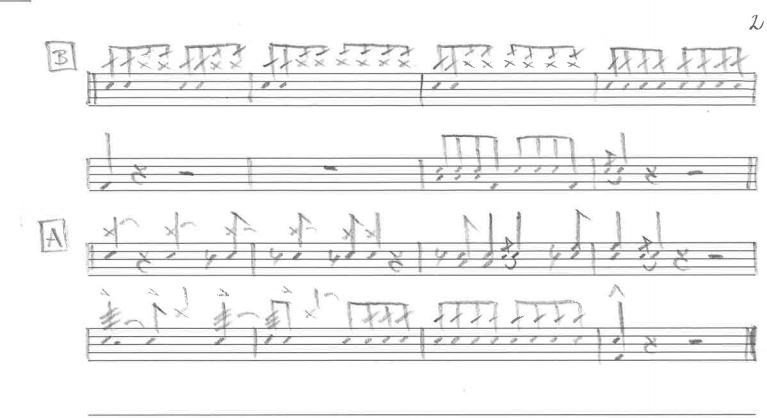

“Daahoud” (Roach, 1954)

Transcription: Daahoud

Video: DaahoudVid

Analysis:

It is interesting how Max builds density and tension - increasing the number of eight-notes played, playing both hands together on the snare and the toms before moving to the triplets (bars 5-16):

Blazing fast triplets played around the set is another staple of Max Roach’s playing (bars 17-24). While “only” single strokes technique-wise, the fast tempo and the ability to flow fluidly around the set was a challenge.

John Riley was of great help with explaining how Max thinks and uses elegant movements and always moving to the new drum on the easy hand. (John Riley Drum Clinic: CLASSIC SOLO PHRASES: MAX ROACH Triplet Phrase, 2014)

Both John Riley’s page on Cross-sticking Combinations in Beyond Bop Drumming(Riley, 1997, p. 60), as well as Thomas Lang’s lesson(Thomas Lang: Applying Technique On The Drum-Set - Drum Lesson (Drumeo), 2015, 07:50), helped me with speed, control, and fluidity needed to play this transcription.

Before the end, Max fills the space between the tom and cymbals hits with straight eighth-notes on the snare drum with the left hand. Playing this type of figure with a weak hand makes it significantly harder and shows technical skills, and creates a special sound. Figures like this with the weak hand were used a lot by Philly Joe Jones.

He ends the chorus with the triplet phrase he began with, rounding out his solo.

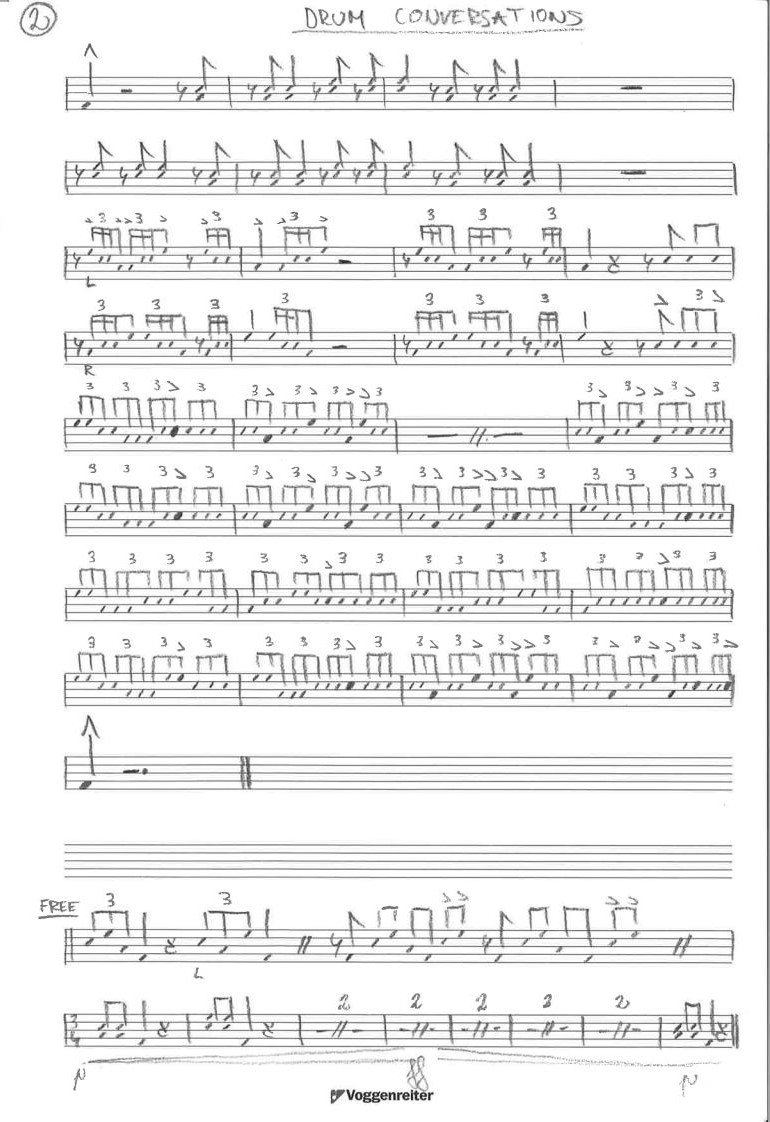

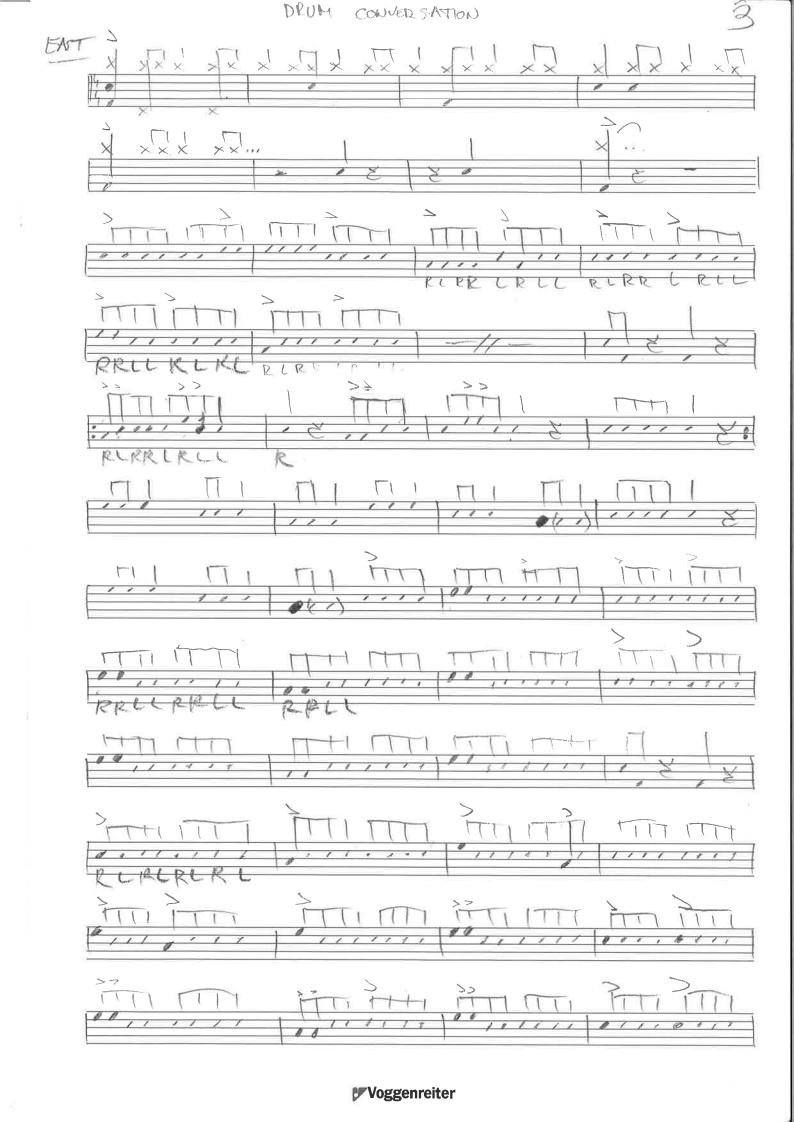

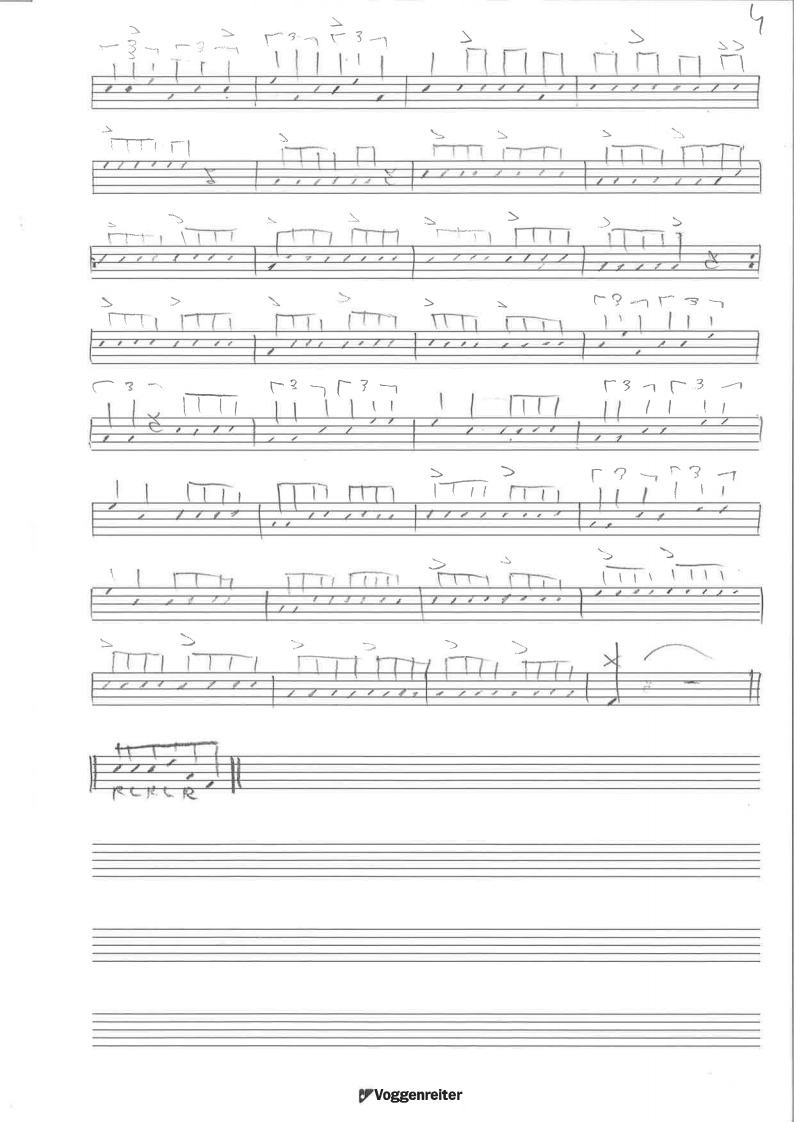

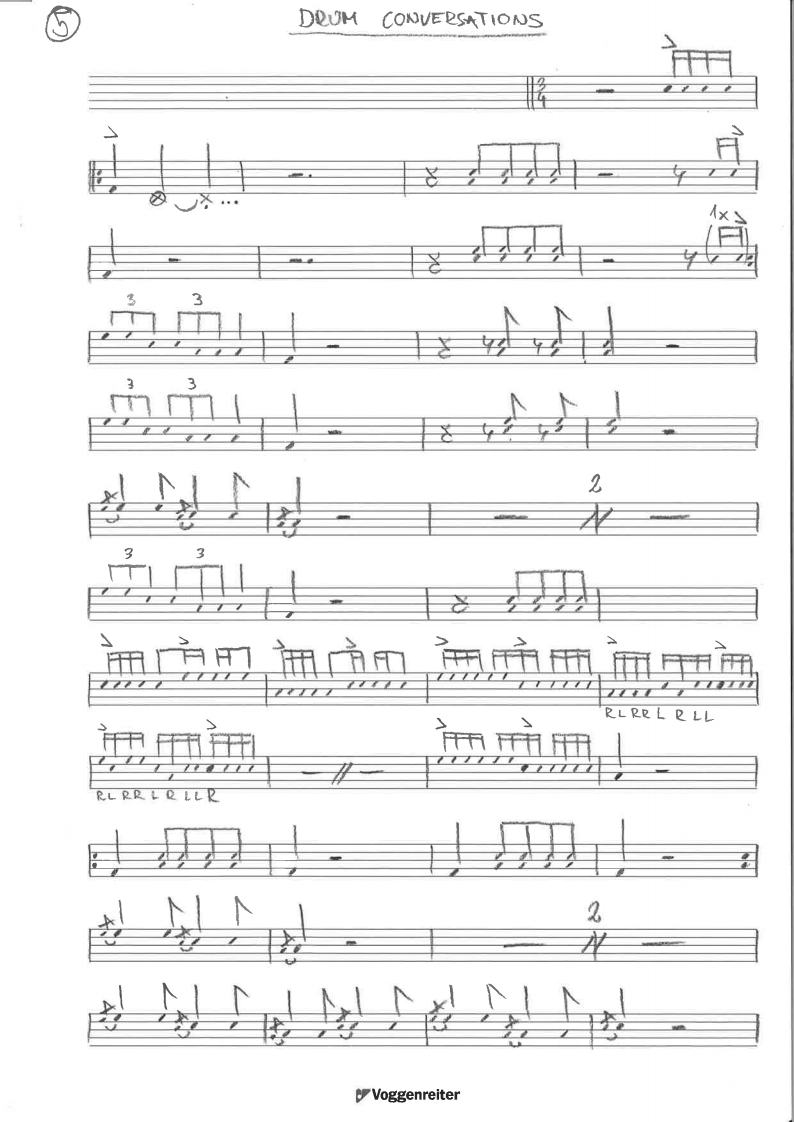

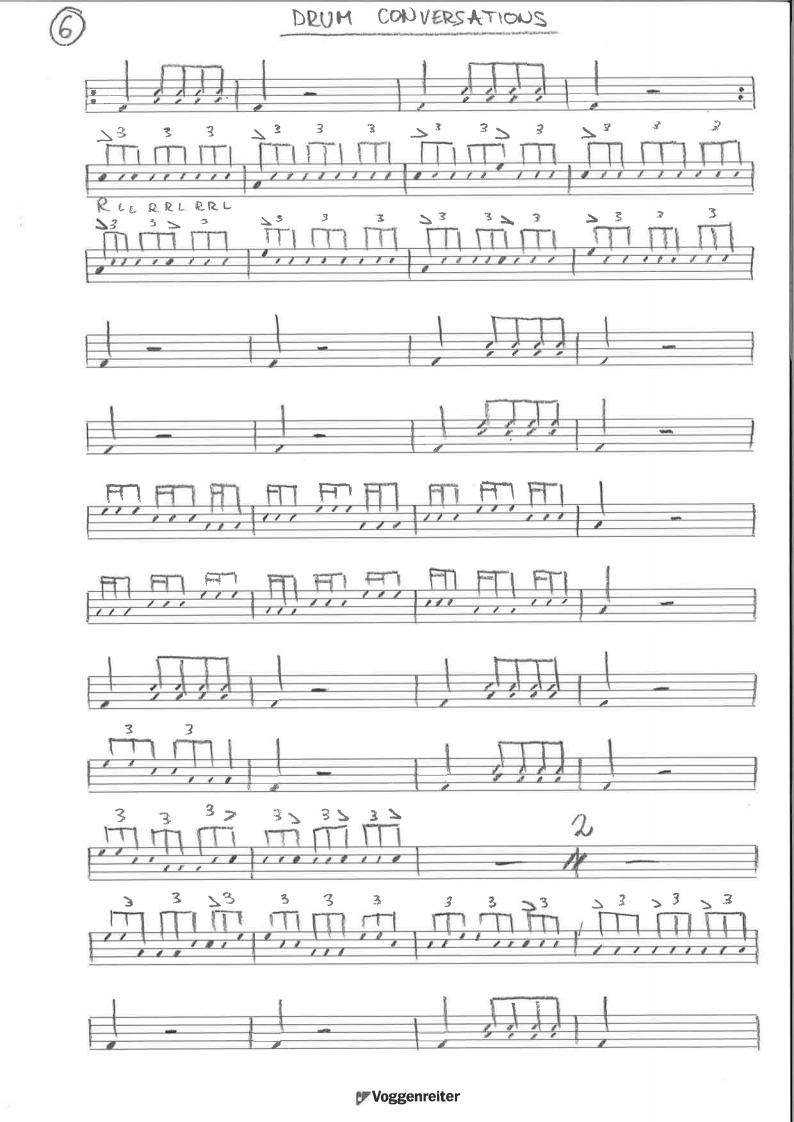

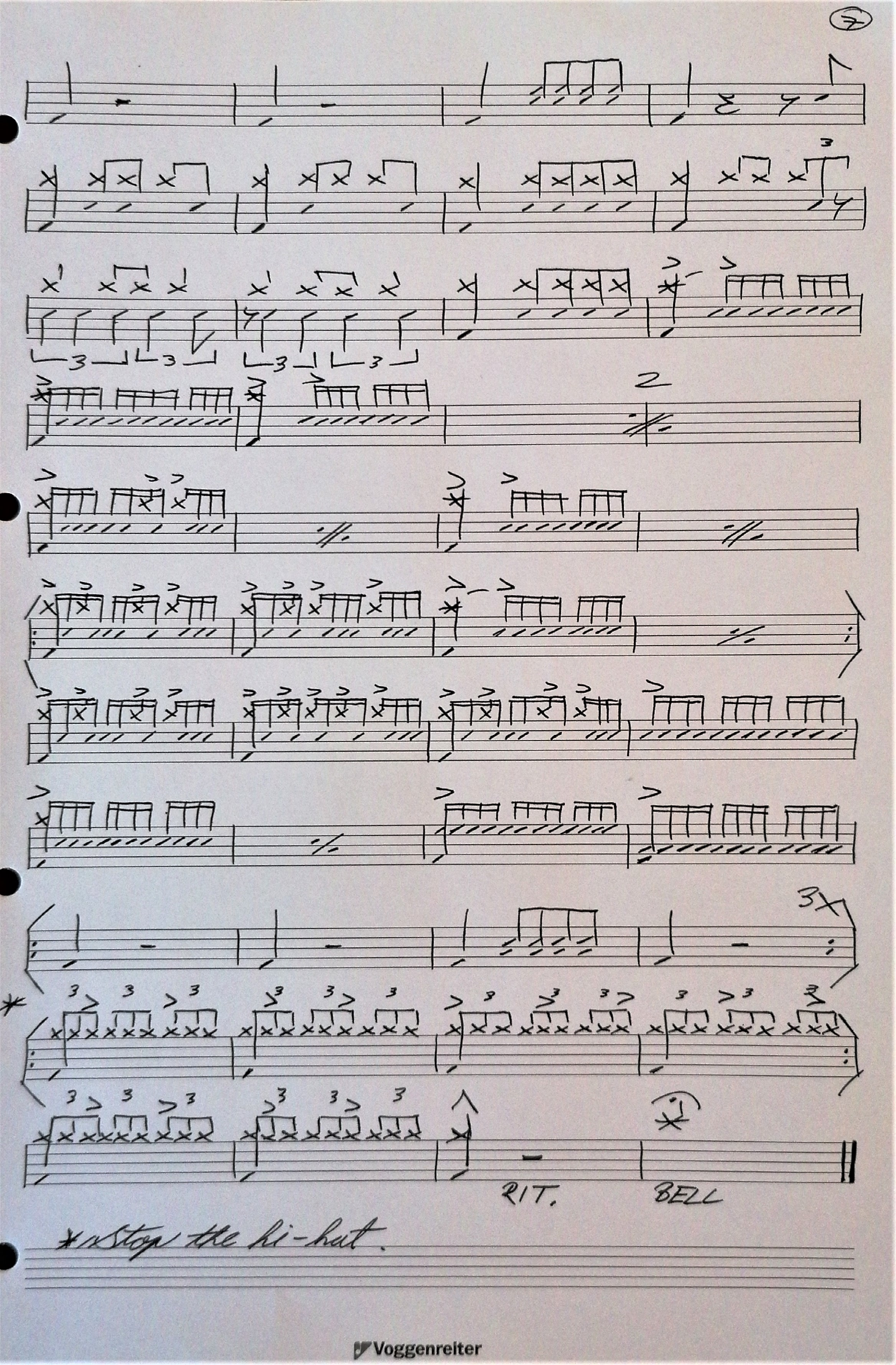

“Drum Conversation” (Roach, 1984)

Transcription: Drumconversation1

Video recorded from transcription: Drumconversation5

Video: DrumconversationVid

Analysis:

This epic solo piece for the drumset has it all from playing free dynamics, different tempos to different ostinato patterns. The ostinato hi-hat pattern in the last segment (pages 5,6,7) was fascinating to me because it brings a completely new dimension to the instrument, and Max was one of, if not the first drummer I could find to use the hi-hat in that way.

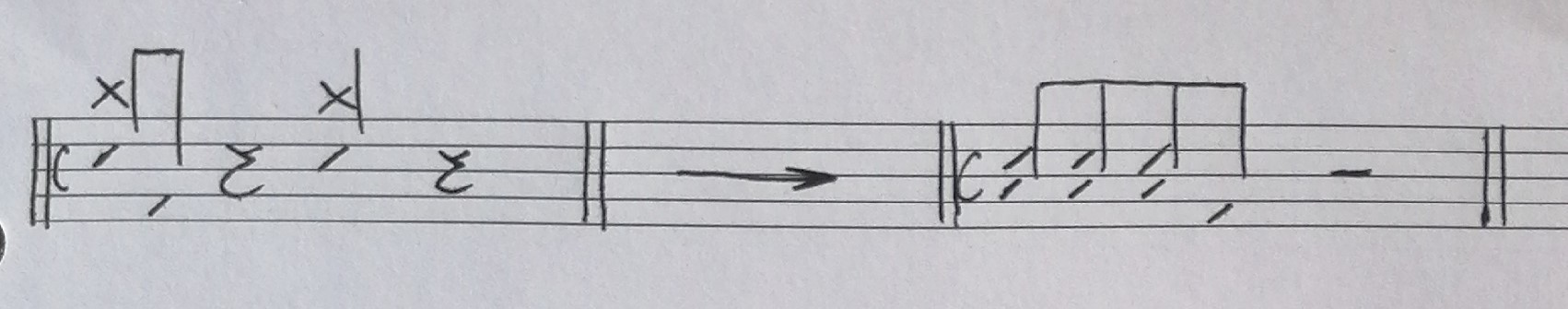

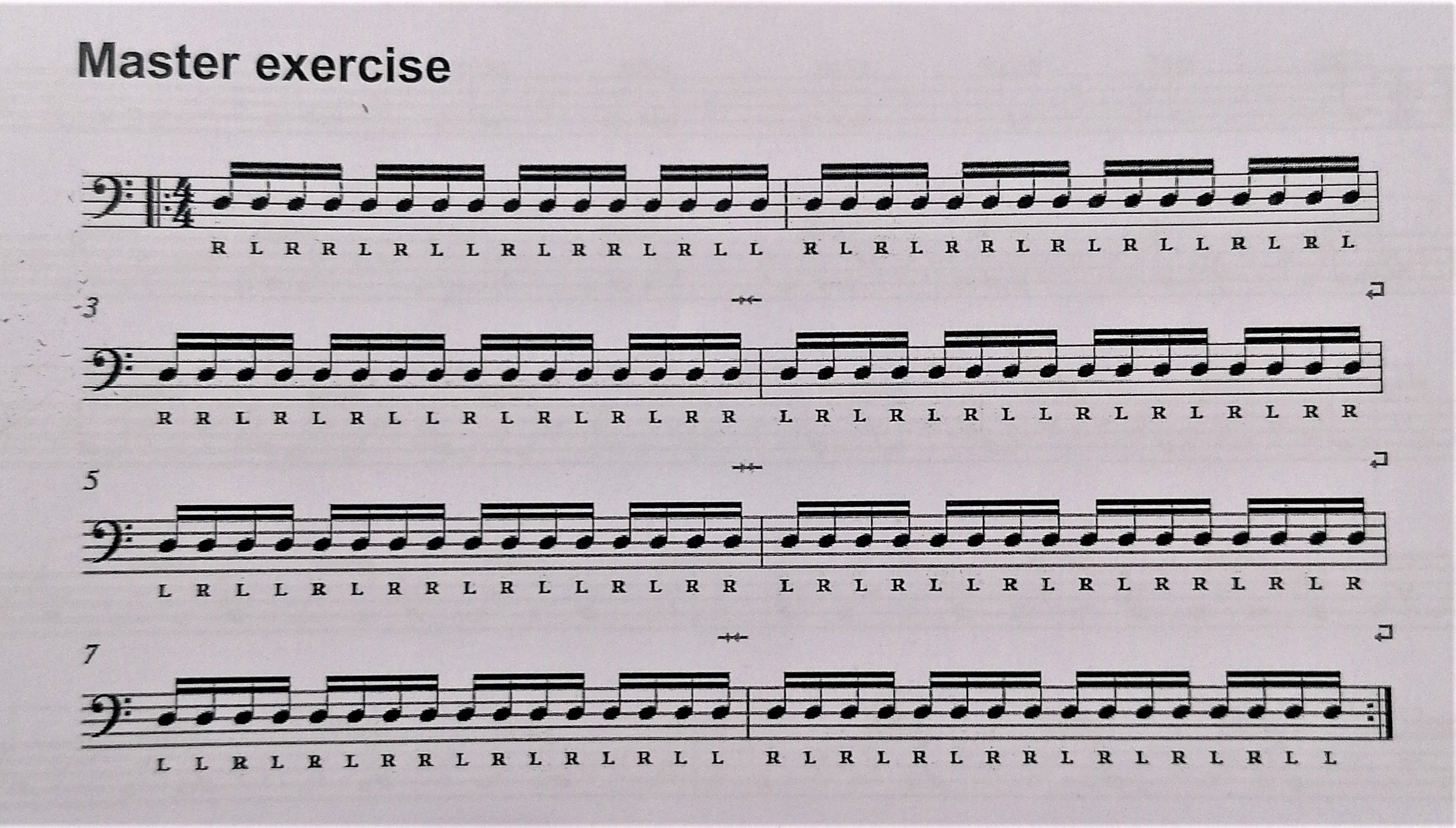

To get comfortable with the hi-hat pattern, I practiced The Master exercise:

With different hi-hat patterns:

Omitting the anchor of the bass drum (patterns 4 and 5) makes the exercise significantly harder but adds more freedom in soloing by allowing the use of the bass drum.

Modern drummers that have expanded this ostinato hi-hat concept include:

Bill Stewart(Bill Stewart - Joe Henderson - John Scofield: Recorda Me - Relaxin at Camarillo, 2021, 15:08)

Antonio Sanchez(Antonio Sanchez: Drum Solo I, 2014)

It is interesting to add how influential Max Roach was also to drummers of other genres. For example John Bohnam clearly paying tribute to Max in the opening of his solo on Moby Dick (Led Zeppelin Moby Dick Full, 2012, 01:07)

As Geoff Clapp mentioned in the interview, trying to play jazz phrases in other genres, for example, with James Brown recordings, is a good way to practice them and makes them easier to relate to and “funky.”

Another suggestion of integration would be to mix genres and drummers. For example:

| Styles (4 bars) | Example |

|---|---|

| Genre 1 | Funk |

| Drummer 2 | Max Roach |

| Genre 2 | Latin |

| Drummer 3 | Philly Joe Jones |

General thoughts:

The soloing style and concept of Max Roach can be summarised as follows:

-

Call and response/question and answer concept. Though this concept is found in most drummers and musicians, Max makes it very clear and easy to identify.

-

Composition. It is truly remarkable how Max invented his own drumming language. Using a minimal collection of phrases, he molds and shifts them around to tell a story. Whether it is his solo drumming concerts or playing in a group, his solos always sound like a composition - organized, logical, melodic.

-

Using rests. Max uses rests to a great effect. He leaves a lot of space in his playing, making his drumming sound open and giving the listener a chance to really understand what he is saying.

-

Repetition. Repeating ideas and developing them. Returning to the same idea after a while.

-

Ostinato and the use of the hi-hat. Using the hi-hat as an active voice in soloing(Concept developed greatly by Mel Lewis, Roy Haynes, Jack Dejohnette, etc.)(Riley, 1997, p. 8)

Max Roach’s drumming is interesting because of its clarity, musicality, and compositional identity, but at the same time, it has its flaws. Using his language and concepts can cause you to sound too “boxy.” Like Geoff Clapp commented in the interview, his playing is very A, B, C, D. Very one-dimensional and straight-forward for modern times. I have found that the right way for me to use his material is to use the concepts and phrases in conjunction with other material. To choose phrases that can be worked on in more than one way ( for example, 3-beat phrases, across the bar phrases, etc.), to use other “tools” (like Tony Williams did with the hi-hat, etc.) or to alter the phrases to make them more interesting and less one-dimensional (see developing phrases).

Tony Williams

“Max is my favorite drummer. I don’t know if I’ve ever said this clearly and plainly, but Max Roach was my biggest drum idol. Art Blakey was my first drum idol, but Max was the biggest.”(Mattingly, 1998, p. 79)

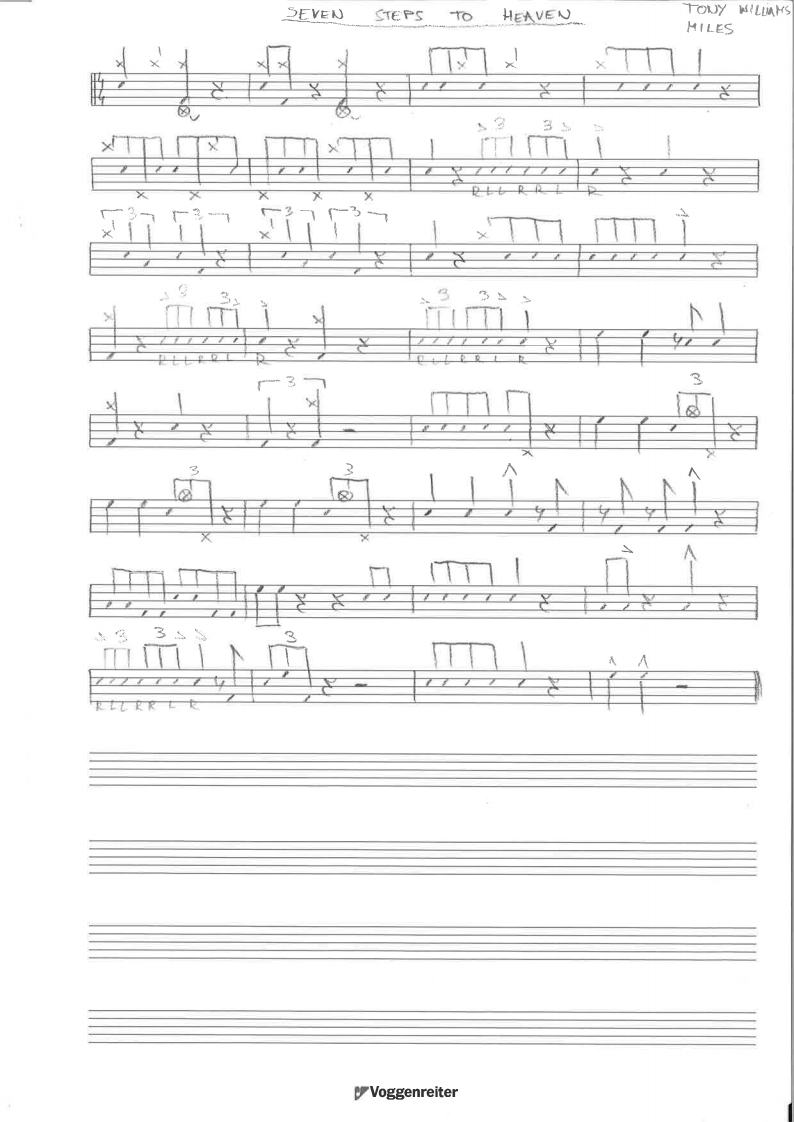

I never really understood this quote. How can that be? He sounded nothing like Max Roach to me. Looking at his playing through the eyes of concepts, the influences are clearer. Art Blakey was a clear influence in terms of groove, power, and sheer energy. Looking at the solo of Seven Steps To Heaven, his first recorded solo:

“Seven steps to heaven” (Davis, 1963)

Transcription: SevenStepstoHeaven

Video: SevenStepstoHeavenVid

Apart from the few similarities phrase-wise, for example, the six-stroke roll in bar 7, one could hardly conclude that Max Roach heavily influenced this solo. However, looking at the solo from the perspective of concepts and tools, there is a clear influence. The clear question and answer motive, the repetition of phrases (albeit changing more rapidly than with Max), the rests between phrases ( punctuating the phrases, letting them breathe), the controlled sound and conviction by which they are played, etc. His playing is very deliberate, controlled, and melodic, and his understanding of storytelling is very mature for such a young age (17!).

Tony also actively uses the hi-hat in his playing (with the foot: bars 5 and 6, with hands: bar 20), truly using the drums as one instrument.

John Riley also explains how Tony took Max Roach’s triplets organized in groups of four (last line in Drumconversation1 and developed them. (Riley, 1997, p. 47)

Tony shows a clear direction on how to improve and build upon the concepts presented by Max Roach.

Philly Joe Jones

“Joe’s debut” (Jones, 1959)

Transcription: Joesdebut

Video: JoesdebutVid

Analysis:

Philly Joe begins the solo calmly as if taking a breath, starting with a classic jazz phrase inspired by “Mop Mop”(Coleman Hawkins - Boff Boff (Mop Mop), 1943). He repeats the phrase twice before beginning to build tension with eight-notes around the drums which he repeats for four bars. In the second A-section, he builds tension by adding ruff’s (a drum rudiment - one of his “signature” sounds), the first 2 per bar, then four ruffs per bar.

For the entire B-section, he changes the rate from eigh-notes to sixteen-notes - building his solo. Worth noting is his use of paradiddles instead of single-strokes ( I have rarely heard Philly Joe use single-strokes when there is an option for double-strokes or paradiddles, etc.). I was not used to playing paradiddles without accents (if we look at the second bar of the B-section, usually we would play accents on all 4 beats, Philly Joe makes this phrase difficult by omitting accents except the ones one beat 1 and 3). He proceeds to build tension by adding more accents in the phrase until the resolution and the high point of the solo in bar 3 of the last A-section.

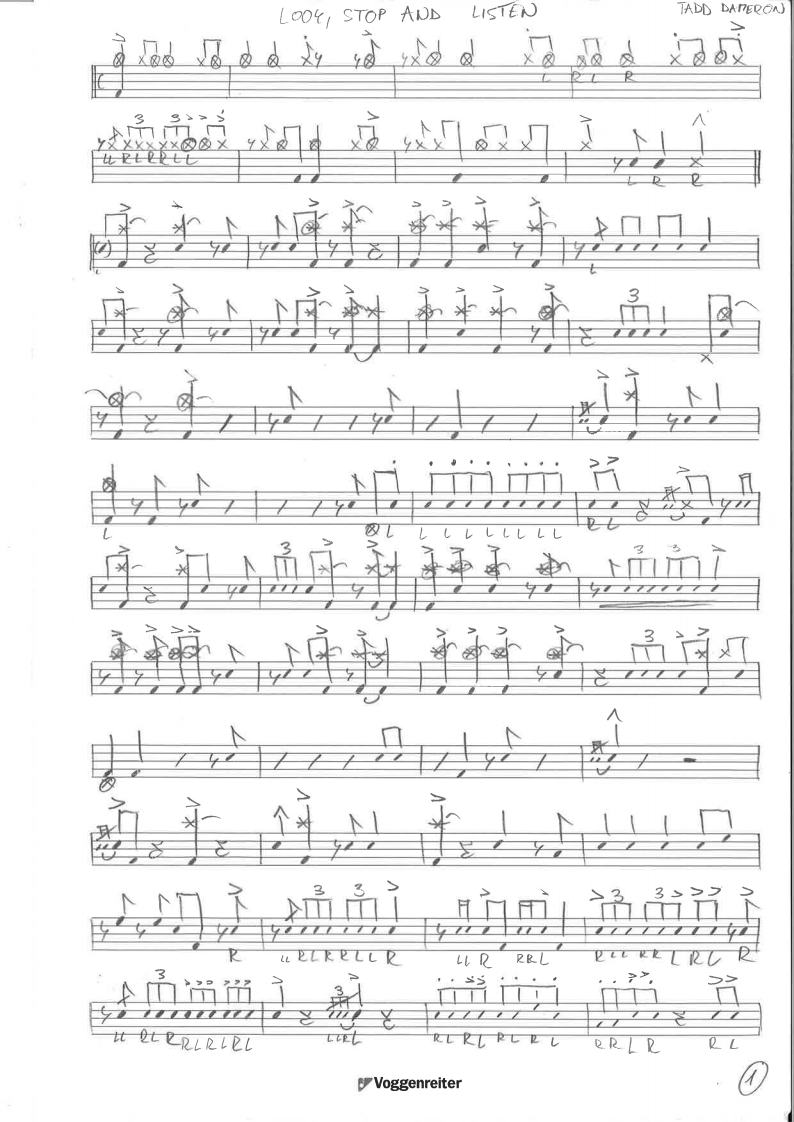

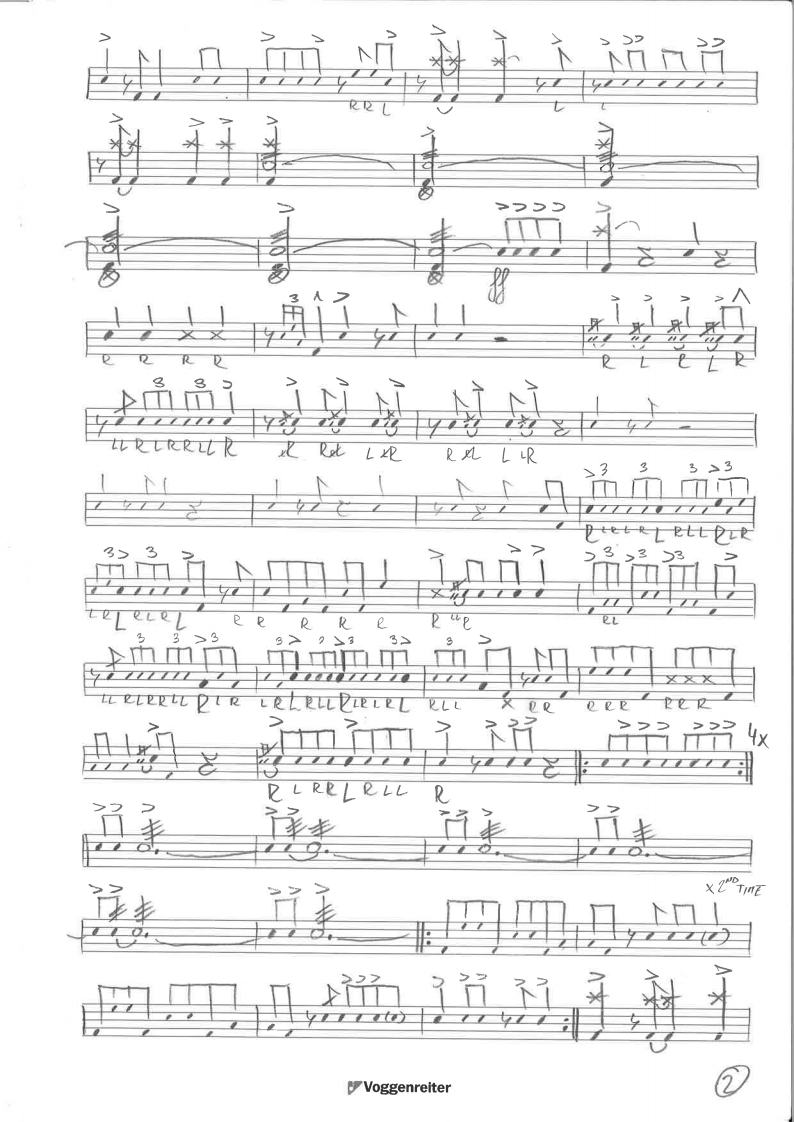

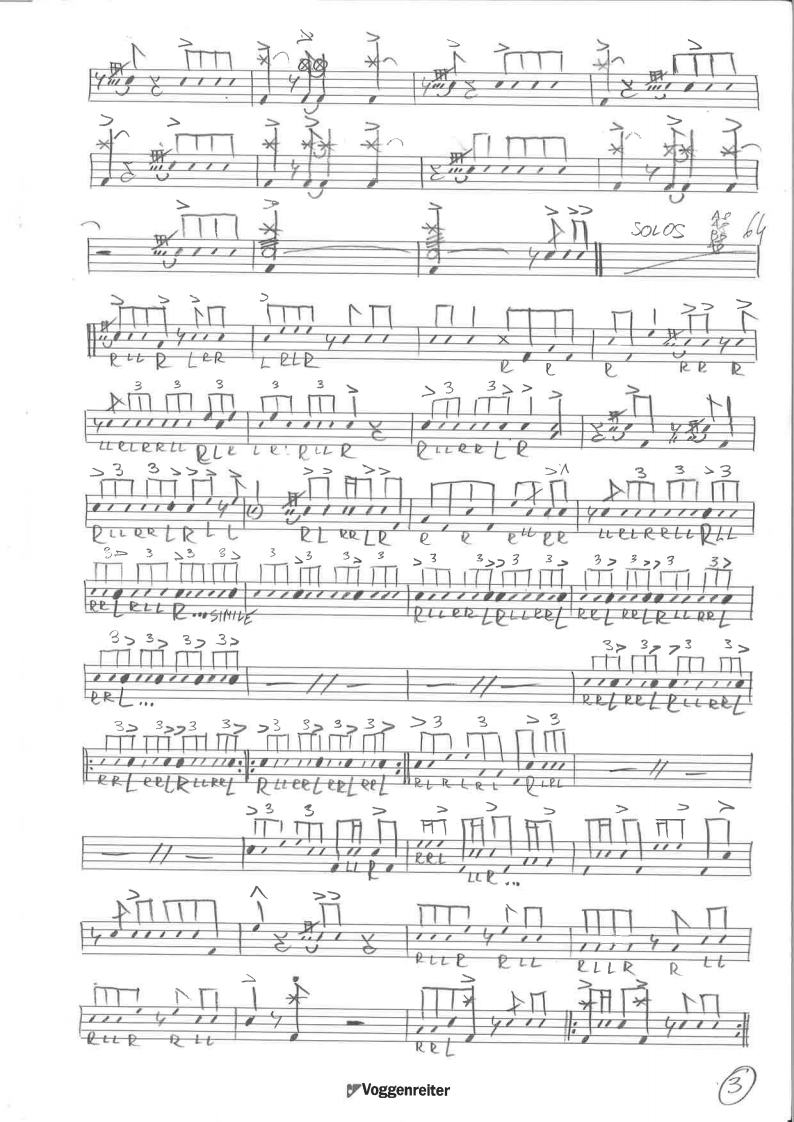

For the last A-section, he returns to the ruff’s combined with double-stroke rolls and stick-on-stick shots (also one of the classic sounds associated with Philly Joe and Roy Haynes). In bar 5, I noticed a subtle change in phrasing (for example, the eight-notes in bars 5-8 seem to be played with a very “straight” feeling, whereas those in bar 5 seem to be more “loose” and swinging.) I noticed similar phrasing changes, for example, in bar 24 of A night in tunisia played by Kenny Clarke. We can find a similar change in the eight-notes at the end of line 8 of the second page of Philly’s solo on Look stop and listen.

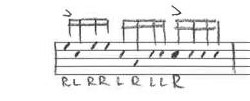

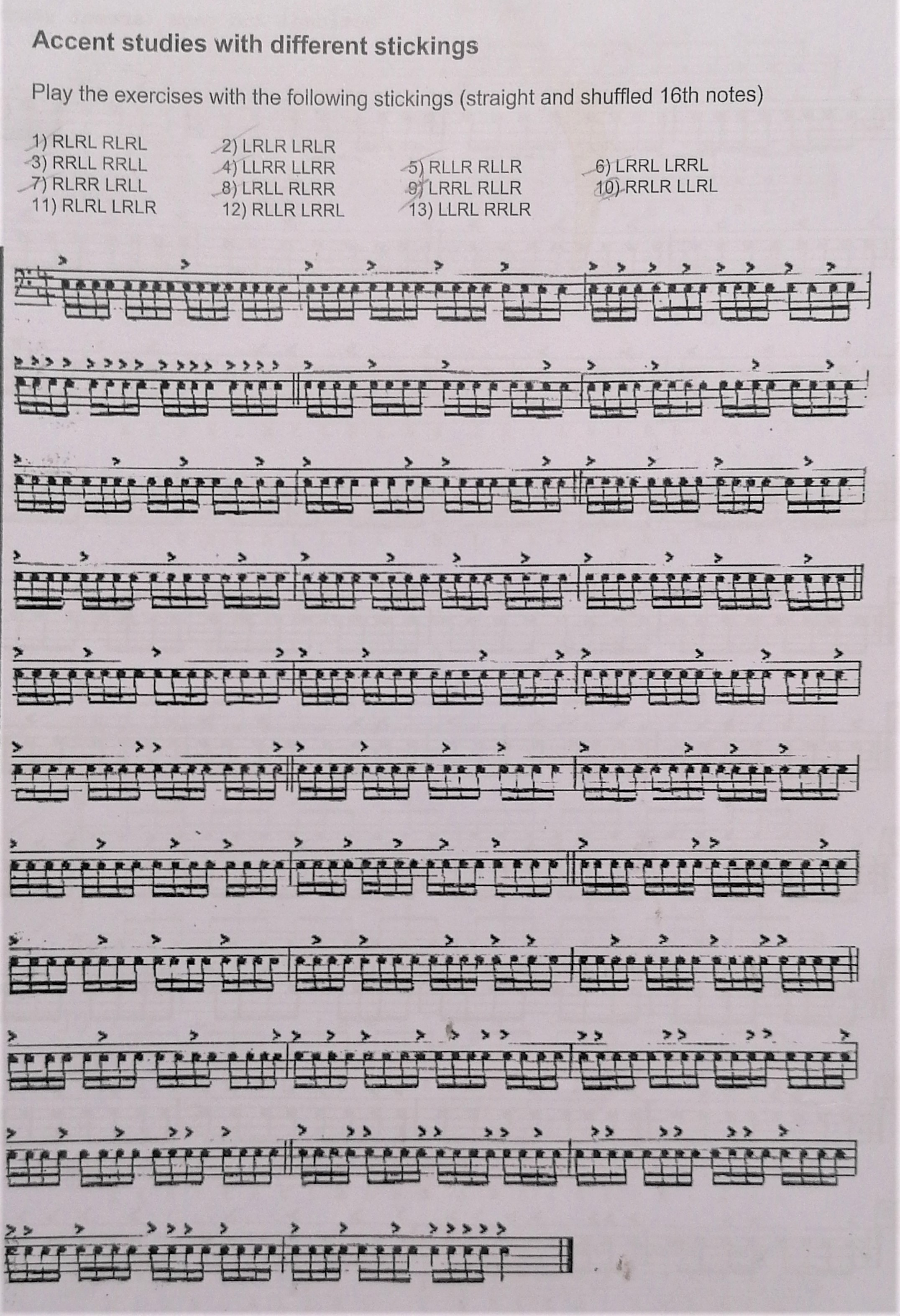

To practice the change between the “straight” and “swing” phrasing, I practiced Accent studies with different stickings:

I practiced the page changing the phrasing every 4 bars, and eventually expanded that to change phrasings every 2nd and later every bar. Since the page deals with practicing accents with different stickings, I have gone through a lot of variations of hand changes quickly and effectively.

To end his solo, Philly Joe played an interesting triplet phrase leading with double bass drum hits and finished the solo with a closed-roll.

I believe that Philly’s solo does not follow the melody here but focuses more on the rudiments, building, and developing the “arc” of the solo.

“Look stop and listen” (Dameron, 1962)

Transcription: Lookstopandlisten1

Video:LookstopandlistenVid1

LookstopandlistenVid2

This epic solo contains almost all of the language and phrases that Philly Joe Jones ever played. It is no wonder that it is in the curriculum as one of the pieces to transcribe and play at the Royal Conservatoire in Den Haag. To prepare, I practiced the Rudimental Ritual (Dawson & Ramsay, 1998, pp. 11–23). Worth noting is that Philly Joe studied Tadd Dameron’s compositions extensively (evident by how he foreshadows what the band will play, sets up sections, etc.). I would encourage everyone to transcribe and play it as it contains almost all of the information about Philly Joe Jones.

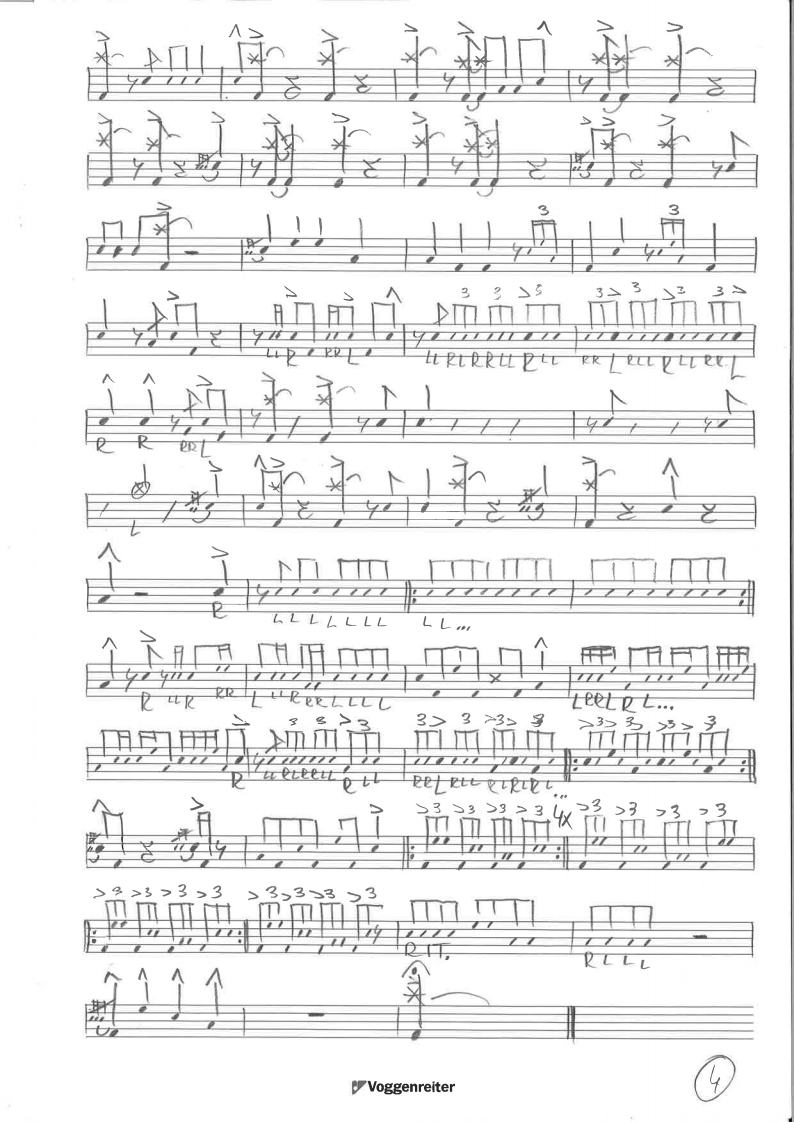

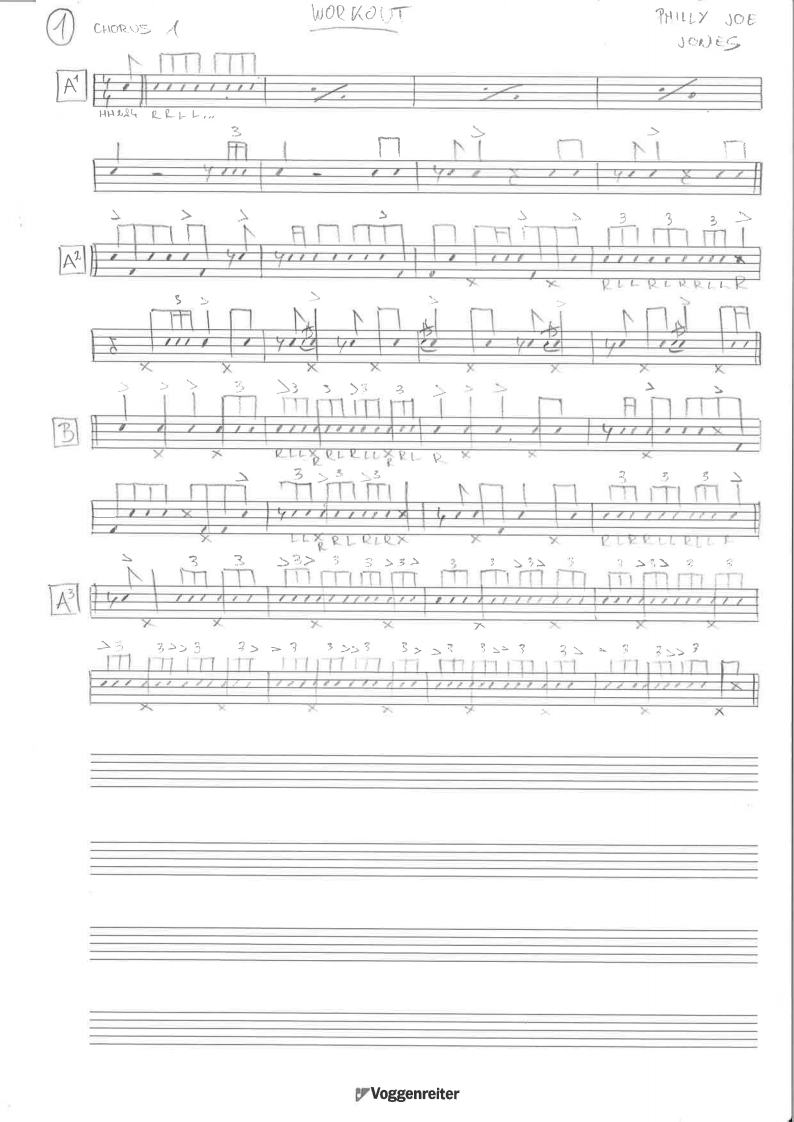

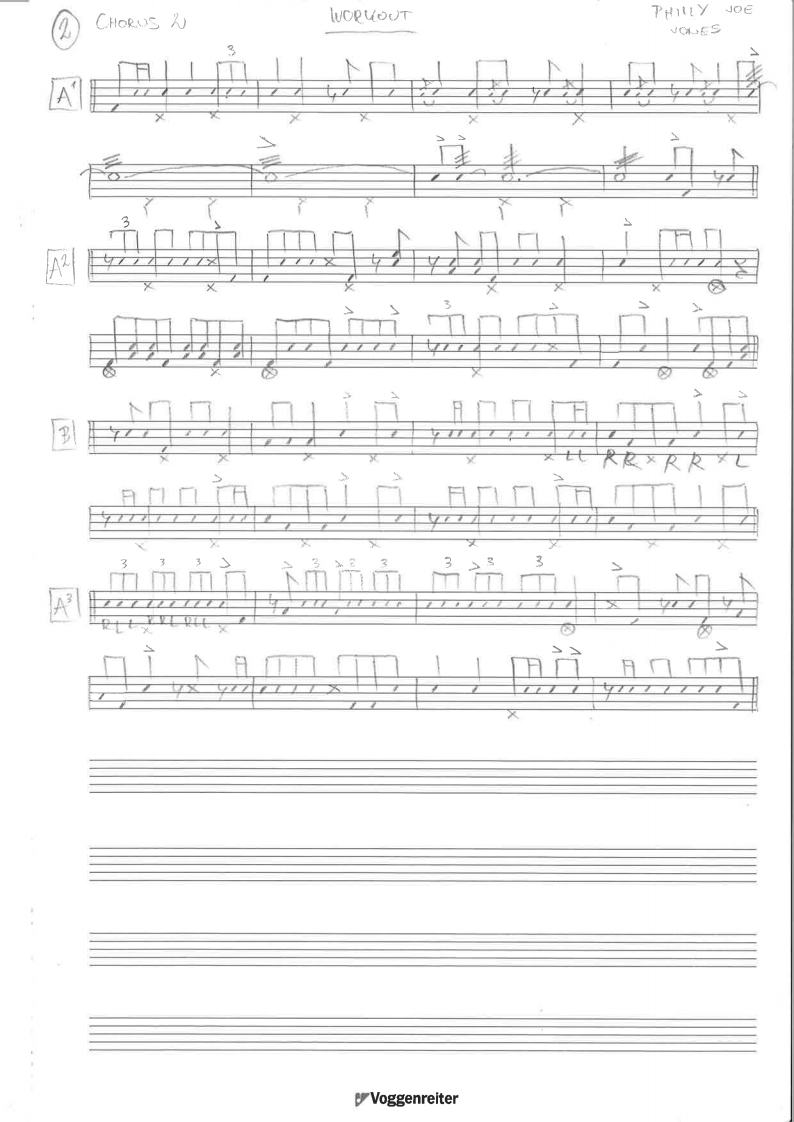

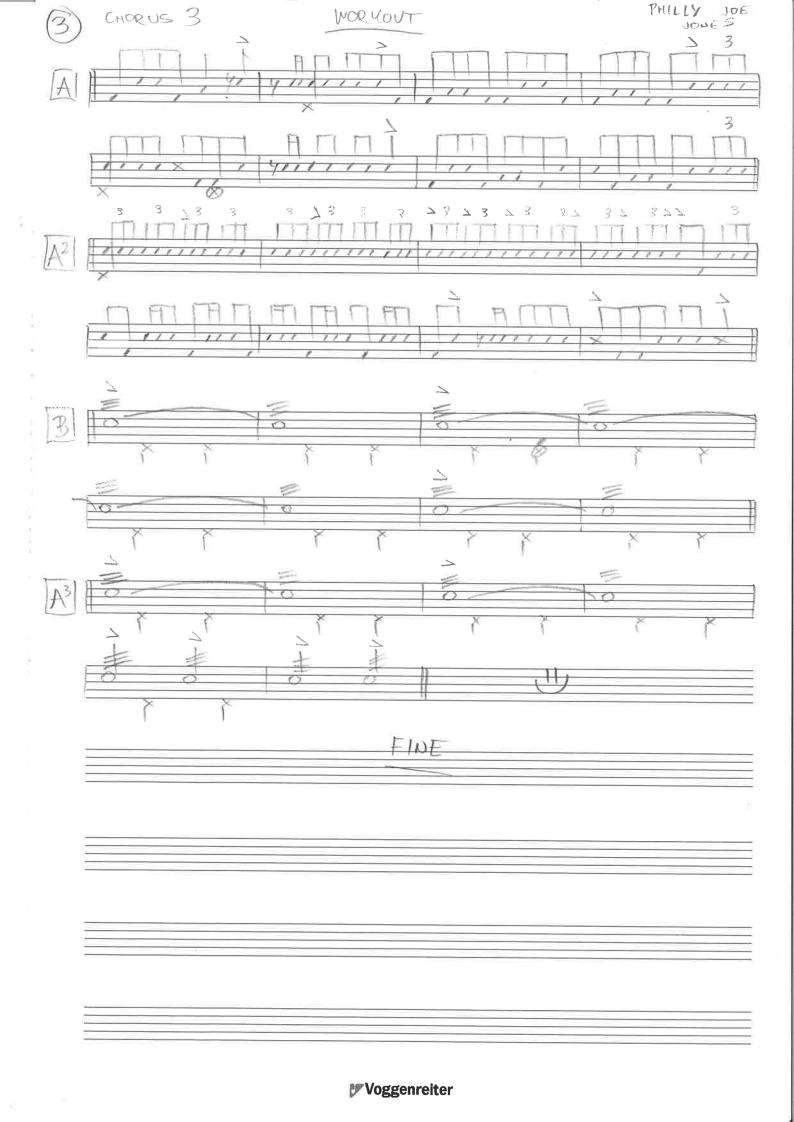

“Workout” (Mobley, 1962)

Transcription: Workout1

I decided to include Workout because it showcases how Philly Joe dealt with a melody using the rudiments since the whole solo closely follows the melody. Worth noting is also his beginning of the solo using double-strokes, the changes of his soloing in different sections, and his use of the closed-roll.

General Thoughts:

The soloing style and concept of Philly Joe Jones can be summarised as follows:

-

Rudimental druming. Philly Joe’s style revolves around the use of rudiments and techniques, which he uses melodically.

-

Repetition. He would often repeat phrases for 4 bars or longer before moving to a second phase.

-

Playing the melody. Usually, his solos closely follow the melody.

Philly Joe Jones is a great resource for discovering the basic techniques and vocabulary of drumming via rudiments and phrasing. Eric Ineke commented in the interview on his great swing feeling, his “dirty/street feel,” as well as his similarities with Kenny Clarke. While a great drummer to research for all the techniques and a great feel, his concept is not without drawbacks. I found that I often fall into the trap of playing too mechanically and thinking in terms of “licks” (patterns or phrases that he played) while playing with the rudimental concept. The other problem is that it is instantly recognizable - as soon as you start a phrase with a flam or a ruff, it practically screams Philly Joe Jones. The solution to this problem is to think and play with the melody in mind first, not focusing on specific phrases that Philly played and only using the rudiments to reinforce and aid that melody or use the rudimental approach to showcase technique or to help build the melody to its climax.

Modern drummers that actively employ a rudimental way of playing include Kenny Washington and his student Gregory Hutchinson:

Kenny Washington

For example, his tradings and solo on the tune “Four” (Miller, 1990).

Transcription: Four1

Video: FourVid

Gregory Hutchinson

For example, in his solo on the tune “Jet stream”(Bernstein, 1995)

Video: JetstreamVid

or on the tune “Wonderful, Wonderful” (Goines, 2007)

Transcription: Wonderfulwonderful1

Video: WonderfulwonderfulVid

It is interesting to see how Gregory uses playing time and comping as a solo tool ( 3rd trading/bar 17). To practice this fast comping and especially the second bar on beats 4 and 4and, the lessons of Todd Zuckermann at Drumeo(The Mystery Of Ghost Notes, 2019) as well as a section on uptempo studies by John Riley(Riley, 1997, pp. 23–29) were invaluable.

All three solos show the same rudimental approach from using and developing the concept to literal phrases that Philly Joe Jones played, upgraded with more advanced orchestrations over the whole set, active use of hi-hat, etc. Even though they are rudimental, they are still deeply rooted in melody.

Roy Haynes

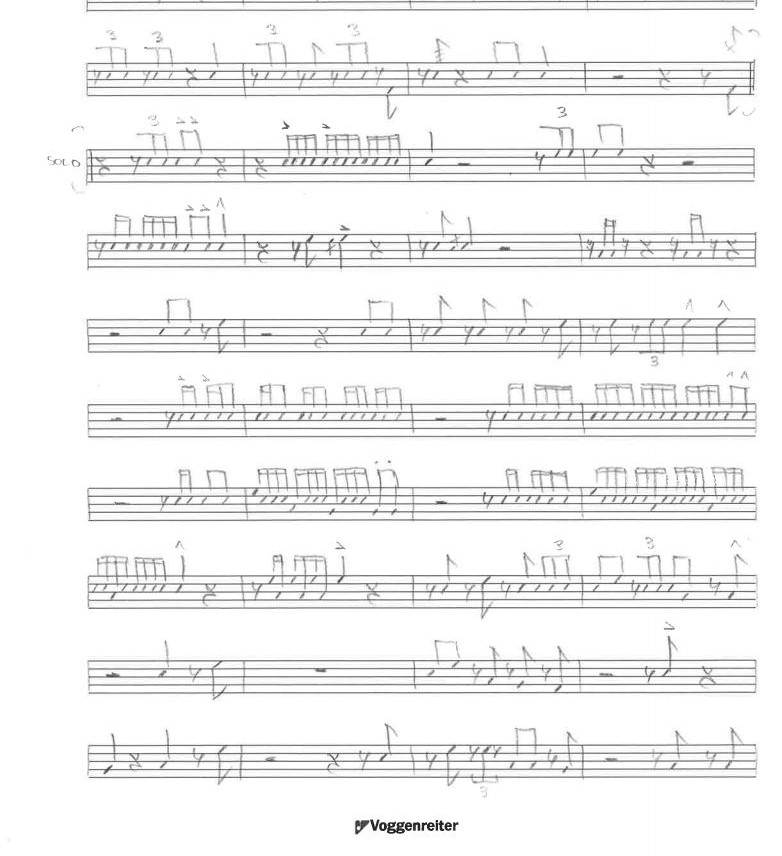

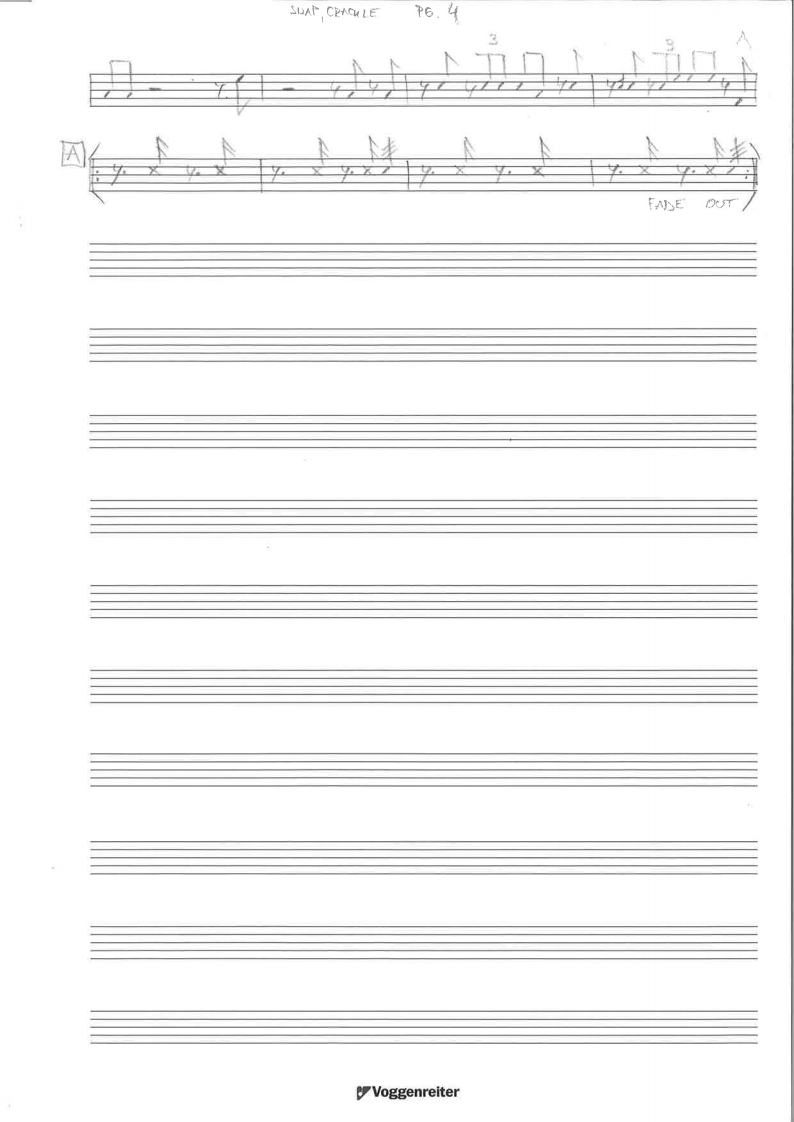

“Snap crackle” (Haynes, 1962)

Transcription: Snapcrackle1

Video: SnapcrackleVid

I have decided to include “Snap Crackle” because it showcases Roy Haynes’s attributes well. The thing that attracts me the most is his sharp, well-controlled sound and phrasing (part of the reason he got the nickname “snap, crackle, pop”). Eric Ineke commented in the interview that his sound and playing are more staccato, compared to the phrasing of Philly Joe or Kenny Clarke. When playing eight-notes and sixteen notes, his phrasing is more “straight” and in front. In contrast, I found that his triplets are really laid back, open and wide. Playing the triplets so wide helps to punctuate and define them. When practicing his triplet phrasing, I have found that I have to consciously exaggerate the spacing between the notes, which has helped me become more aware and in control of where I place the notes - in turn making my triplets “sing” more.

He plays the solo accompanied by a bass line. Similarly to Max Roach’s solo on Mama or, for example, on Gregory Hutchinson’s solo on McThing (Greg Hutchinson - McThing (Live In Montreal 1995 w. Christian McBride ).Mp4, 2011, 02:37), we can observe the space they leave in their playing for the bass to come through and shine.

Roy’s playing is also very melodic and deliberate. He plays notes that are very melody-oriented (for example, the last two lines on the first page), and he has a strong sense of the call-and-response concept.

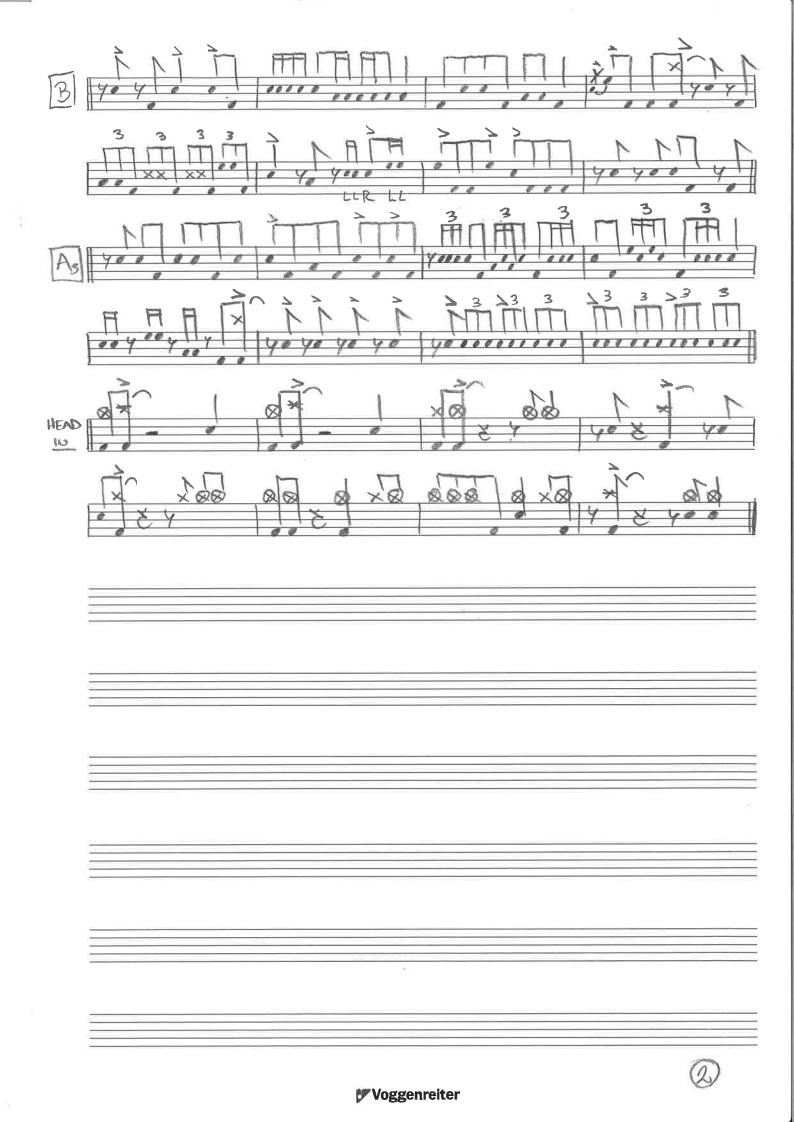

“In walked Bud” (Haynes, 1958)

Transcription: InwalkedBud1

Video: InwalkedBudVid

Roy Haynes starts after the bass solo, beginning his solo quietly as not to take away from the bass solos atmosphere. In the first chorus, Roy chooses only to play the melody, interpreting it on the drum-set, again showing his melody-oriented approach. This concept of playing literal melodies was greatly expanded upon by Ari Hoenig (Jazz Drumming Delight: Ari Hoenig When The Saints Go Marching In JazzHeaven.Com Video Excerpt, 2011), even tuning his drums to pitches to help with the melody. After I experimented with playing and singing the melody of the song out loud while simultaneously playing the solo, I noticed that I tend to focus less on playing “licks,” and my solos become more logical, connected, and interesting.

Inspired by Jeff Hamilton’s rendition of Caravan (Bag Show 2013 Jeff Hamilton Caravan. Drums Solo Batterie, 2015), I experimented with playing literal melodies: CaravanVid

In the second chorus, Roy expands and builds his solo. He uses the hi-hat as a separate voice ( bar 2 of A2), with his iconic phrases: use of sixteen-notes (bar 2 of the B-section), his stick-on-stick triplets ( bar 5 of the B-section), and sixteen-note triplets (bar 3 of A3). He ends the solo with accented triplets leading to the head ( similar to Kenny Clarke, Art Blakey, etc.)

General thoughts:

The soloing style and concept of Roy Haynes can be summarised as follows:

-

Melody oriented. Roy takes the melody of the tune or creates melodies with rhythms when playing his solo.

-

Staccato phrasing. His tight sound, in conjunction with his phrasing, adds a new element to playing drums.

-

Using the whole instrument. He involves the hi-hat as an active voice much more than other drummers when comping and soloing.

To practice playing the melodies, I started to play just the literal melody with no ornamentation on the snare drum, gradually incorporated the bass drum, and later orchestrated it over the drum-set. I also sang the melody of the tune when listening and playing solos, as well as sang the solos themselves (inspired by the way Kenny Clarke singes his solos while he is playing them).

Because of his melodic approach, loose comping style, phrasing, and the use of the whole instrument in innovative ways, Roy Haynes is often referred to as the “father of modern drumming” (Drummer, 2020).

Modern drummers that actively employ a melodic way of playing include Bill Stewart and Brian Blade:

Bill Stewart

For example, his playing on the tune “Recorda me” (Joe Henderson Jazzfestival Bern 1998, 2014, 46:25-48:50). Video: RecordameVid

Bill eases into his solo by playing just the song’s rhythm for a full chorus before altering it! He follows the melody closely, usually incorporating the “hits” or accents in the melody into his solo. His melodic variations on the toms and his use of over-the-bar phrases are a great way to observe how melodic drumming can be evolved.

Brian Blade

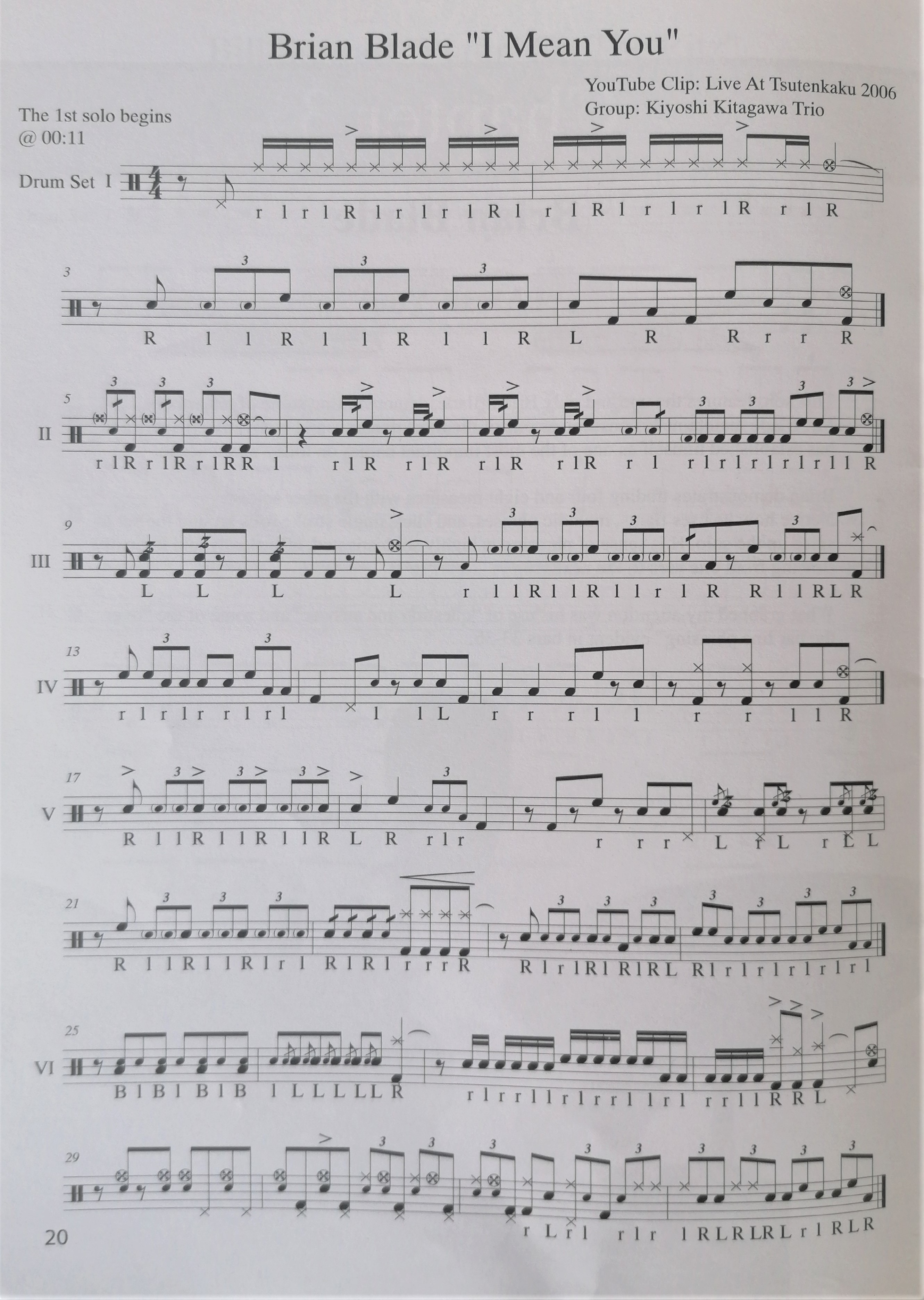

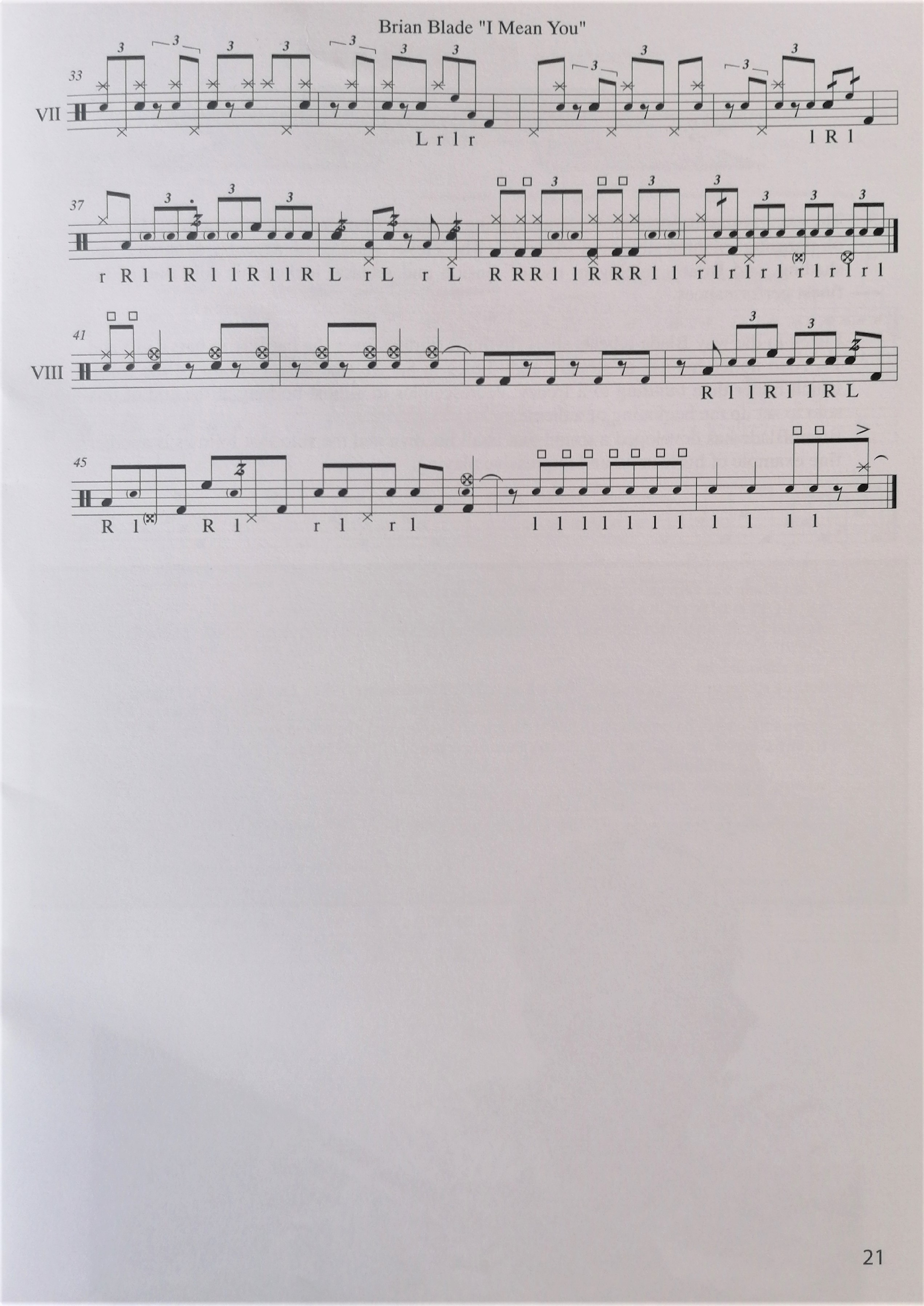

For example, in the tradings on the tune “I mean you” (Kitagawa, 2006).

Transcription:Imeanyou1 (Milenković, 2011, p. 20)

Video:ImeanyouVid

In the soloing or Brian Blade, we can observe similar concepts. Playing simple phrases and focusing on creating melodies around the drums.

Both solos show how melodic drumming, in conjunction with rudiments to support them, is a solution to solving Max Roach’s “boxy” linear problem as well as Philly Joe’s more mechanical and “lick” oriented rudimental problems.

Dynamics

The other tool I noticed both drummers greatly employ is that of dynamics. Looking at the history, I can’t say I find dynamics in terms of crescendos or rapidly changing dynamics from p to FF from one phrase to another. In history, dynamics are more present in terms of accented and unaccented notes rather than being consciously used as a tool. There are notable exceptions, of course, for example, the last line on page 2 of Max Roach’s Drumconversation.

Inspired by the soloing of both players as well as with Mark Guiliana’s lesson on Drumeo where he talks about dynamics (Mark Guiliana: Exploring Your Creativity On The Drums (FULL DRUM LESSON) - Drumeo, 2018), I started practicing and making a conscious effort to include dynamics into my soloing.

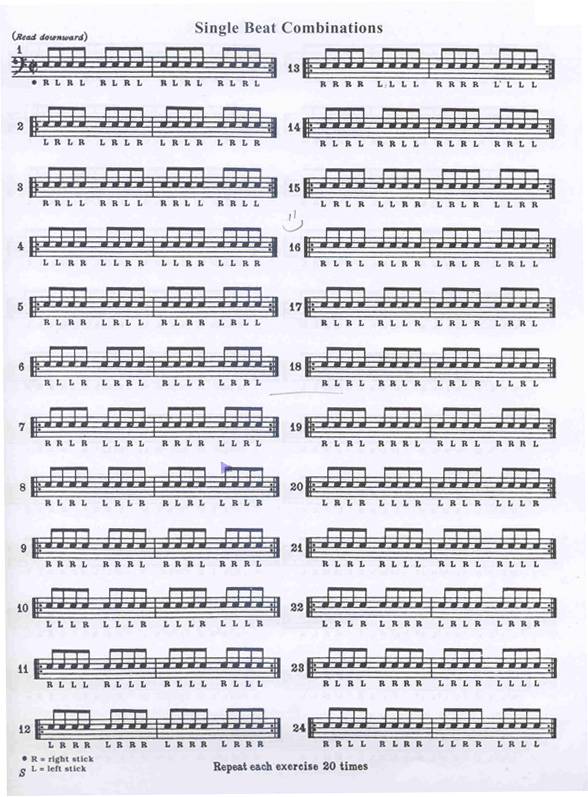

To practice dynamics, I included it into my daily practice routines. For example, when practicing Stick Control:

I practiced each system 20 times. For the first 10 repetitions, I would change dynamics every two bars (bars 1 and 2 - pp, bars 3 and 4 ff, etc.). For the last 10 repetitions, I would build a crescendo from pp to ff for the first 5 repetitions, then a decrescendo for the last 5 before moving to a new system.

Also helpful was a lesson by Max Roach of playing all four limbs simultaneously and doing a crescendo and decrescendo with one of them. (Stanoch, n.d.)

Setting limitations

One of the ways to spark creativity is to limit yourself. Practicing, I often limited myself deliberately to see how many variations and melodies I could come up with.

Some limitation ideas:

- Playing only on the snare.

- Playing the B-part of a song on the cymbals.

- Playing by using only toms and the bass drum without using rudiments.

- Practicing leaving as much space between notes as possible.

Here I experiment with playing a solo only on the snare and hi-hat played with the foot:

Video: LimitationssoloVid

A note on video recording

Starting my research, I planned to experiment with my findings in live concerts and jam sessions. Because of the situation, I resorted to video recordings, and that has had unexpected benefits.

On the one hand, it simulated the pressure of a live concert or recording session. The second benefit was that I had had an opportunity to observe myself playing on a level that I had never before been able to. That resulted in changes to my playing. For example, it made me aware of how high my ghost notes were and helped me redefine my ideas on touch and volume. It helped with my posture by realizing that my snare drum was positioned too low etc.

I can wholeheartedly recommend video-recording yourself practicing to everyone.

Conclusion

Researching drum soloing, I have tried to explain and describe a process that generally develops organically. It develops through trial and error, listening, experimentation and experience.

Through my process of choosing, transcribing, and analyzing the solos of the master drummers of the bebop era, I have successfully identified their fundamental concepts and ideas that permeate every drum solo. These concepts include the Call and response/question and answer concept, the rudimental concept, and the melodic concept. I have also successfully identified several tools or minor concepts that help create and develop creative and interesting drum solos. The tools include repetition, developement of a phrase, using rests, creating a “carpet” of sound, composition, phrasing, sound, dynamics,etc.

By focusing on and practicing the concepts and tools in isolation, I have gained valuable insight and knowledge of each element, as well as finding and designing exercises that aid with their development, thus helping me with the process of integrating the playing of the masters into my own vocabulary and developing my soloing.

I have also shown how each of the master drummers inspired today’s modern drummers and how they took their ideas and concepts, integrated them into their own playing, and developed them to a new level.

Starting my research, one of my goals was to hopefully trace some of the phrases of the masters and see how they changed to fit the modern style of drumming. Surprisingly, I could not find a clear developmental method, usually finding that the phrases have remained unchanged and are still used in the same manner as they were, albeit with minor orchestration changes.

I hope that my findings can help other drummers and students develop their own soloing and creativity, as much as they have helped me.

Appendix

Interviews

“Eric Ineke”

I have interviewed Eric Ineke, a Dutch jazz legend and my professor at the Royal Conservatoire The Hague.

“Geoff Clapp”

I have interviewed Geoffrey Clapp, a versatile master drummer based in New Orleans.

References

Antonio Sanchez: Drum Solo I. (2014, January 17). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved February 22, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zd8OgyyTnEw

Bag Show 2013 Jeff Hamilton Caravan. Drums solo Batterie. (2015, March 11). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved January 6, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uvwCwLuPxP4

Bill Stewart - Joe Henderson - John Scofield: Recorda Me - Relaxin at Camarillo. (2021, February 3). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved November 11, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lS72s7Pff8E

Busta Rhymes - on “biting” in hip hop; Chance The Rapper - BURN conference, pt. 2 (Popkiller. pl). (2016, October 4). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved December 22, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K4tZcktiqIA&t=301s

Cambridge Dictionary. (n.d.). 2. a musical performance was given by one person alone, or a musical…. Learn more. Retrieved May 17, 2020, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/solo

Chapin, J. (2002). Advanced Techniques for the Modern Drummer: Coordinated Independence as Applied to Jazz and Be-Bop, Vol. 1 (Book & CD-ROM) (PAP/COM ed.). Alfred Music.

Coleman Hawkins - Boff Boff (Mop Mop). (2013, July 6). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved March 1, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HddiVFhhtSQ

Dawson, A., & Ramsay, J. (1998). The Drummer’s Complete Vocabulary As Taught by Alan Dawson: Book & Online Audio (Pap/Com ed.). Alfred Music.

Drummer, M. (2020, May 9). Roy Haynes: The Hippest Of The Hip. Modern Drummer Magazine. Retrieved May 12, 2020, from https://www.moderndrummer.com/2009/12/roy-haynes-2/

Elvin Jones: Drum Solo -1978. (2018, March 7). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved January 19, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=msbg4iaW5nE

Greg Hutchinson - McThing (Live In Montreal 1995 w. Christian McBride ).mp4. (2011, July 15). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved January 10, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2qbkczu5g9Y

Gregory Hutchinson-Hide & Seek(solo)- Live @ the Jerusalem Theater 3June2009 1080p. (2009, June 28). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved January 25, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9ZjcoJm60pI

Jazz Drumming Delight: Ari Hoenig When The Saints Go Marching In JazzHeaven.com Video Excerpt. (2011, August 18). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved January 6, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9m4UJQbGUH8

Joe Henderson Jazzfestival Bern 1998. (2014, January 18). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved December 27, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KmY4r0dhEDs&t=2933s

John Riley drum clinic: CLASSIC SOLO PHRASES: MAX ROACH Triplet Phrase. (2014, September 12). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved November 2, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QuVJYMdjB-0

Led zeppelin moby dick full. (2012, November 25). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved February 14, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r9-42mu1D9Y

Mark Guiliana: Exploring Your Creativity On The Drums (FULL DRUM LESSON) - Drumeo. (2018, April 26). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved October 7, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5A0fw7-HKYE&t=3525s

Mattingly, R. (1998). The Drummer’s Time: Conversations with the Great Drummers of Jazz. Hal Leonard Corporation.

Michael Brecker - El Nino. (2007, August 19). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved January 16, 2021, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Wem-GMT9NYA

Milenković, D. (2011). The Magnificent 7. Self-published.

Miles Davis. (n.d.). Www.Goodreads.Com. Retrieved April 21, 2020, from https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/822979-anybody-can-play-the-note-is-only-20-percent-the

Pablo Picasso. (n.d.). Quotefancy. Retrieved January 5, 2021, from https://quotefancy.com/quote/884436/Pablo-Picasso-A-plagiarist-steals-from-one-person-A-true-artist-steals-from-everybody

Pigeons, P. (2016, August 25). The Fine Line Between Biting and Paying Homage. Complex. Retrieved December 22, 2020, from https://www.complex.com/pigeons-and-planes/2016/03/rap-biting-paying-homage/lyrics

Reed, T. (1996). Progressive Steps to Syncopation for the Modern Drummer (Ted Reed Publications) (32042nd ed.). Alfred Music.

Riley, J. (1997). Beyond Bop Drumming: Book & CD (Manhattan Music Publications) (Pap/Com ed.). Alfred Music.

Riley, J. (2004). The Jazz Drummer’s Workshop: Advanced Concepts for Musical Development. ModernDrummer.

Riley, J., & Thress, D. (1994). The art of bop drumming: Book & online audio (manhattan music publications) (Illustrated ed.). Alfred Music.

Royal Conservatory Den Haag, Kruger, S., & Schlarmann, F. (n.d.). Royal Conservatory jazz department KonCon DRUMBOOK. Self-published.

Snoop Dogg - ALL THESE RAPPERS SOUND THE SAME? BEEF Or Nah? + Kendrick Lamar - 2015 Whoo Kid. (2015, May 20). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved December 22, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5bMBIBKPPm4

Stanoch, D. (n.d.). A lesson with Max Roach. Modern Drummer - Jazz Drummer’s Workshop. Retrieved October 11, 2020, from https://davidstanochschoolofdrumming.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Max-Roach-Transparent-Sound-Article-Modern-Drummer.pdf

Stone, G. L. (2009). Stick Control: For the Snare Drummer. George B. Stone.

The Mystery Of Ghost Notes. (2019, January 23). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved December 4, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RUI5C5O5maE

Thomas Lang: Applying Technique On The Drum-Set - Drum Lesson (Drumeo). (2015, May 9). [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved October 20, 2020, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Tia3nieOu0o

Wilcoxon, C. (1945). 10300202 - The All-American Drummer. Ludwig Masters.

Wilcoxon, C. (1979). Modern Rudimental Swing Solos for the Advanced Drummer. Ludwig.

Discography

Bernstein, P. (1995). Signs Of Life [ALBUM]. Criss Cross.

Byrd, D. (1956). Byrd’s Word [ALBUM]. Savoy.

Brown, C. and Roach, M. (1954). Clifford Brown & Max Roach [ALBUM]. EmArcy.

Brown, R. (1997). Live at Scullers [ALBUM]. Telarc.

Dameron, T. (1962). The Magic Touch [ALBUM]. Riverside.

Davis, M. (1957). Bags’ Groove [ALBUM]. Prestige.

Davis, M. (1957). Walkin’ [ALBUM]. Prestige.

Davis, M. (1957). Cookin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet [ALBUM]. Prestige.

Davis, M. (1958). Relaxin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet [ALBUM]. Prestige.

Davis, M. (1959). Workin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet [ALBUM]. Prestige.

Davis, M. (1961). Steamin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet [ALBUM]. Prestige.

Davis, M. (1963). Seven Steps To Heaven [ALBUM]. Columbia.

Goines, V. (2007). Love Dance [ALBUM]. Criss Cross.

Gordon, D. (1963). Our Man In Paris [ALBUM]. Blue Note.

Haynes, R. (1959). We Three [ALBUM]. New Jazz.

Haynes, R. (1960). Just Us [ALBUM]. New Jazz.

Haynes, R. (1962). Out of the Afternoon [ALBUM]. Impulse!.

Henderson, J. (1992). Lush Life: The Music of Billy Strayhorn [ALBUM]. Verve.

Hubbard, F. (1963). The Artistry of Freddie Hubbard [ALBUM]. Impulse!.

Jones, P.J. (1959). Drums Around the World [ALBUM]. Riverside.

Jones, P. J. (1959). Showcase [ALBUM]. Riverside.

Jones, P.J. (1960). Philly Joe’s Beat [ALBUM]. Atlantic.

Jones, P.J. (1971). Trailways Express [ALBUM]. Black Lion.

Kitagawa, K. (2006). Live At Tsutenkaku [DVD]. Atelier Sawano.

Miller, M. (1990). From Day to Day [ALBUM]. Landmark Records.

Mobley, H. (1960). Soul Station [ALBUM]. Blue Note.

Mobley, H. (1961). Roll Call [ALBUM]. Blue Note.

Mobley, H. (1962). Workout [ALBUM]. Blue Note.

Monk, T. (1958). Misterioso [ALBUM]. Riverside.

Redman, J. (1995). Spirit of the Moment – Live at the Village Vanguard [ALBUM]. Warner Bros.

Redman, J. (1998). Timeless Tales [ALBUM]. Warner Bros.

Redman, J. (2000). Beyond [ALBUM]. Warner Bros.

Redman, J. (2009). Compass [ALBUM]. Nonesuch.

Roach, M. (1961). Percussion Bitter Sweet [ALBUM] Impulse!.

Roach, M. (1984). Long as You’re Living [ALBUM] Enja.

Rollins, S. (1957). Saxophone Colossus [ALBUM]. Prestige.

Transcriptions

“Scrapple from the apple”

“A night in tunisia”

Media

“Scrapple from the apple video”

“A night in Tunisia video”

“Gregory Hutchinson variation”

“Mama Variations”