At least one thing we can be certain of in these uncertain times is that octopuses have beautiful gardens.

This exhibition is part of my PhD research that explores the line between art and everyday life. For me, artistic research is about using art to experiment and discover (hopefully the unexpected), in my case, to find about how art and life connect, how they overlap, and what the edges and boundaries that seem to divide them look and feel like. In the early days of my research, I imagined a line separating art and life like a line drawn on the ground, like something to be stepped over. It soon became something more like an invisible barrier to be broken through until I found myself walking along it, a bit like a balancing act. And now I am aware that as a practising artist I am constantly moving in and out, from art to life, and back again. And though I had originally asked the question about whether there is a line between art and life, it has become clear that my intention has never been to define that line and decide what lies on each side. I prefer to blur and confuse the borders, to muddy the waters between tools and ornaments, art objects and functional objects, playing or doing something for real, the ordinary and special, overlooked and noticed. My intention is to debunk the concept of a line that separates and divides and show that nothing is as simple as it might first appear. In 1959 Allan Kaprow coined the term happenings to denote a type of art event or situation that explored and blurred the line between art and daily life. He wrote numerous essays and one, rather playfully, includes clearly set out instructions on how to blur art and life. It begins with the instruction that “The line between the happening and daily life should be kept as fluid and perhaps as indistinct as possible.”[9] His investigations explored the idea of daily life as something performed and he makes the following observation, “When you do life consciously, however, life becomes pretty strange – paying attention changes the thing attended to – so the happenings were not nearly as lifelike as I had supposed they might be”.[10] As I think about the line between art and life, I am aware of the contradictions and the resulting ambiguities, and how something special can become ordinary and then special again. The line between art and life is fluid and flexible, tangible and then intangible, visible and invisible, and rather than separating, it traverses and links, joins together, creating new spaces and revealing new ways of seeing. This is similar to what happens when I walk and when my awareness shifts and slides into and out of what I see, notice, remember, think and feel.

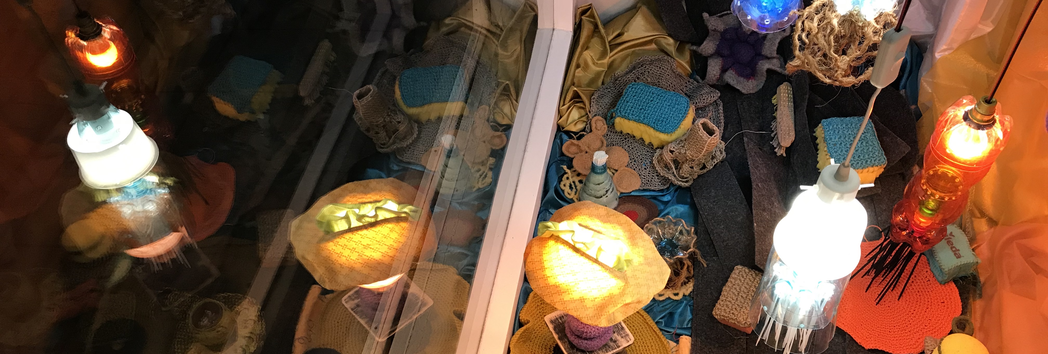

I stand at my window with the octopus’s garden and look in. I spent three days in the relatively narrow windowsill space (300 cm x 88 cm) setting up An Octopus’s Garden of Silly Delights. I suspended the mesh from which to hang the lamps, draped the shimmery lining fabric and hung the electrical cords and felted containers. I laid the “sea floor” made from leftover dark grey carpeting and sewn into jaggedly undulating sections, and arranged the doilies, the sponges, brushes and table lamps on the windowsill. All this work was interrupted by having to climb in and out through the gap between the jewellery display cases to go outside to see how it looked from outside. Sometimes I feel that looking is underrated. Sometimes I would like to sit like an anthropologist in my umpire’s chair and just look and observe.[11]

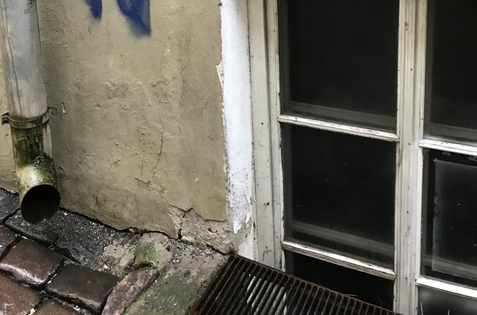

Shown like this my work keys into the existing practice of window dressing. And though there is no competition, it does vie for attention with the other galleries, cafés and shops on this street. My window is like a shop window, like a seasonal Christmas or Easter display, it’s like a handicraft stall, yet it is none of these. Like them it is always accessible, but I also like to think that it is accessible in another sense. Having used easily available, lowly materials like fabric remnants, leftover plastic, yarn, bits of rope, I want to show that anyone can do this. The cut edges, visible stitches, cable ties and straightforward placement of objects on top of and next to one another demonstrate simple, everyday techniques. It is my attempt to show that when I make art (I consider the installation of work in this window part of my practice) it can be indistinguishable from non-art tasks like setting a table, mending a pair of shoes or hanging up fairy lights. However, one of the differences between ordinary tasks and making art is that art need not be useful in an everyday, practical or functional sense, but what it does do is allow me to ask questions – nonsensical or silly questions like “What if octopuses had gardens and they looked like this? What if octopuses made things, crocheted, stitched, glued and cobbled together strange objects or lamps from leftover plastic containers?

It has been snowing, so although beautiful, sometimes the footpath is slippery and sometimes walking in the soft snow is like walking across shifting sand. In places it even has the colour of sand.[12] I can see the footprints ahead of me and though I might be the only one on this street now, I know that other people have walked here before me. As I walk, I think about Adrian Tchaikovsky’s octopuses and how we could learn from them. In his novel Children of Ruin there is an entire civilisation peopled by octopuses.[13] Their living conditions are becoming cramped and they are constantly fighting with one another, both physically and mentally. But unlike humans they are fluid in their allegiances and even in their principles. There will be an argument, with positions being upheld and argued but not necessarily by the same individuals throughout the confrontation. The argument remains fixed but the individual octopuses are easily convinced and change sides quite effortlessly. The colours changing and moving across their bodies express their emotions visibly, and this means they can’t hide their feelings from each other. This means they can’t waste time trying to conceal, lie, obscure, supress, deceive or feign.

As I try to imagine a utopian future, I ask what it would be like if people were more like these octopuses.[14] Not fixed in categories, not having to have an opinion and then stick to it. We are led to believe that having principles and sticking to them is important. We follow the news, develop opinions, we take a stand and hold firmly onto this position. But what if we loosen, become loose, loosen our ideas and opinions, and become floppy, flexible and fluid, and like Tchaikovsky’s octopuses, effortlessly find ourselves arguing for the other side. How about we step off the merry-go-round for a moment to look around to see things differently and to think differently. Rosi Braidotti talks about thinking differently and I admit this walk is heavily influenced by her nomadic theory. It provides me with an approach that moves through and across established categories and helps me to understand the blurring of boundaries. Her theory, inspired by nomadic people and cultures, is actually a way of thinking, one that questions and defies fixed conventions and established approaches.[15] It is a kind of mental ability that is flexible and fluid, that moves from “one set of experiences to another [with a] quality of interconnectedness. ”[16] And because the nomad is on the move, in a state of transit, the view is constantly changing – nothing is fixed for long, because as Braidotti says, “The nomad’s relationship to the earth is one of transitory attachment and cyclical frequentation”.[17] And how about we laugh a bit. This might help humanity regroup and reconsider. But if emulating octopuses sounds too far-fetched then maybe we can look to humans of the past. Janet Wolff, for example, paraphrases the idea about writers in the seventeenth century for whom “it was common, and in no way shameful to write for commission on political matters, and moreover, to change one’s allegiance without apology.”[18] I’d like to live in a world where admitting mistakes and changing one’s mind was easier. Hanna Guttorm, writing about how not to lose hope when faced the difficulty of living in a complicated, unjust world suggests “we need to try. Try harder” but then, mid-thought she makes a U-turn and ends the line with, “maybe softer”.[19] Let’s try softer. For me, this is an example of thinking differently. I am so used to the idea of trying harder and it has never occurred to me that the opposite might also be an option.

A few streets away from my octopus’s garden a couple of enterprising curators have come up with a solution to the current closure of galleries and have set up a temporary gallery going by the name of “1. märts” in an empty shop on Väike Karja Street. I accidently went to their recent opening as I was walking home after my first day of setting up my exhibition. [20] It was taking place on the street outside the closed shop. I was stopped by a friendly “Hello!” as I stormed past with long rolls of cardboard under one arm and offered a cup of hot mulled wine. I like it when ordinary everyday life collides with less ordinary moments, such as when I went to buy milk from the local shops and ended up in the funny little shoe shop next door to the convenience store and came home with milk and a nice pair of boots. This collision on Väike Karja Street was a smooth one, between hurrying home after a tiring day and finding myself, with no effort on my part, no debating whether I should go, whether I could be bothered and who would be there, what I would wear, and would I know anyone and so on, and being suddenly at an exhibition opening.

There are a number of established art galleries in the old town, all closed, but some have adjusted their exhibitions with 24-hour spotlights and re-positioned the work and video screens, thus taking into the consideration the viewer on the street. As I walk to my octopus’s garden, I pass Draakon Gallery and I look in. [21] The gallery has large windows onto the street. There is an interesting and eclectic collection of various objects on the windowsill, large painting-like works made of hanging strips are spot-lit and seem to be arranged for maximum visual effect from the street. A strange red spot-lit shaggy coated figure stands before a large picture of a zebra. At the back there is a shelf with what look like toys and maybe board games.

I walk on, anticipating the first view of my window. Everything in my window is fine, nothing has fallen over, and all the lights are still working, which is a relief because replacing the bulbs will be an event in itself, since I will have to open the jewellery cabinet, remove all the jewellery, climb in and over the work, change the bulbs and then retreat in a way that nothing is disturbed. Mind at rest, I keep walking.

What I find especially exciting about art is that it doesn’t have a responsibility to be or do anything. Art is free and isn’t required to fix or solve anything. It can tell the truth or not. It can make things clearer or blurrier. It can organize or mess things up. It can make things happen or not. And as art critic Hal Foster suggests, artists can take a bad thing and make it worse.[22] Maybe it’s useful to know that a bleak future is always a possibility and maybe it is good to imagine that and think through what it might be like. Art can present or suggest options for the future, but these don’t have to be viable options. They can even be stupid suggestions. It’s good to have all the options on the table, and to have the freedom to consider obviously bad or inappropriate solutions…if we want. It is possible that it is precisely the hare-brained schemes and utopian visions that will revitalise our ways thinking and seeing the world. In 1917, Shklovsky wrote about how art can cause us to see things we might not otherwise notice simply because they are familiar.[23] He illustrates his idea with a quote from Tolstoy’s diary. Tolstoy is cleaning and describes his movements as habitual and unconscious to the point where he can’t remember if had already dusted the sofa, or not. Because he couldn’t remember, it was the same as if he had not. Shklovsky continues, “And so, in order to return to our limbs, in order to make us feel objects, to make a stone stony, man has been given the tool of art.”[24] So to make us feel things, to impart the sensation of things as they are perceived and not as they are recognised, art uses different tactics to makes objects unfamiliar by what he calls estrangement, or as it is also translated “defamiliarization” and “making strange”,[25] which aims to interrupt the smooth flow of automatised perception and allow us to see things, as if for the first time. For me, as I walk, it is the unfamiliar situation caused by the pandemic that heightens my awareness and that helps me to see things, including art, differently.

I continue walking. Hobusepea Gallery has an exhibition with minimalist grey and white paintings on the walls.[26] This exhibition doesn’t communicate directly with the viewer on the street and even though the paintings are spot-lit I feel like someone with a bad seat in a theatre, where I can’t see the stage head-on. This gallery has a downstairs exhibition space in the cellar but the blind in front of the only window that provides a view down into the cellar space is drawn and all I can do is imagine what the work down there looks like. A couple of doors down at HOP Gallery the exhibition is a slide show that faces directly towards the street.[27] It’s clearly visible and the voiceover coming from a speaker directed into the street is audible. The slide show with its richly contrasting black and white photographs of such things as a merry-go-round, a decorative sculpture in a well-tended garden and the sky with bits of trees peeking into the frame, is set deep in the space, thus turning the black box of the gallery into part of the work.

I double back. I want to see how my window looks when approaching from the other side. It looks fine, and I take a left turn. A little further on there are a number (four, I think) of empty shops with displays. They are part of a series, since they all have the same A4 information sheet with something about a fairy tale Christmas in the Old Town and in larger letters it says, “The street as an art gallery”. The text also has the maker’s name and their ideas. The displays are visually connected by their predominant use of white shapes and forms, and striking lighting. They are bright and cheerful looking. I am not sure whether these windows are intended as art, or is it design, or something else. I suppose the title “The street as an art gallery” is a clue, but these also look like shop window displays, except that the products for sale are missing. There is no enticement to buy, nothing to want, nothing to own. All I can do is look. This sets me off thinking about categories, whether it’s important to identify or label what these are. What difference does it make if I know these displays are art. And what difference does it make if I look at them as if they were art.

One problem in the world is inequality; this is one aspect of the current dystopia. There is currently talk of certain people in positions of power unfairly jumping the queue to be vaccinated, [28] ]and countries arguing about supplies and which vaccine, and so on. Meanwhile, countries like Moldova, the poorest in Europe, can’t afford any vaccines.[29] Where is the fairness in that? Now, imagine a place of equality, maybe it’s in the octopus’s garden or maybe it’s on this windowsill behind my computer screen that I can see as I write here in my flat. It’s a place where everything is equal. I don’t mean that everything is the same or that they aren’t distinguishable from each other. I also don’t mean that we can see them all equally well at the same time or that all of them are even visible. But what if we look at them is if they all have equal value? To help us imagine this, let’s look with the eyes of someone who is drawing.

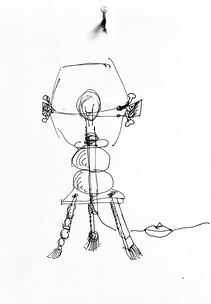

I am sitting at my desk and beyond it is a windowsill with objects on it and beyond that the window. My eye and pencil follow the multiple lines of reflected light along the rim of the glass as it curves down and becomes the side of the glass. On its way it meets the upward curve of the plastic horse’s tail that gently rises to meet the horse’s rump. Almost directly at the point where the tail and hindquarters join, a vertical line shoots straight up to describe the side of a bottle of eyedrops directly behind the horse. These lines not only describe the edges of the glass, the horse and the bottle but they also define the borders of the negative space created by these objects, as well as the side of the pot of pencils, the glassy smoothness of the Alvar Aalto vase and beyond it the tiny triangle of window frame, with its lines of cracked paint. [30] And this negative space is not empty. Short, subtle lines describe the texture of the linen cloth covering the windowsill and a strong dark line marks the edge of the shadow made by the vase. The way the line morphs and changes as I draw is like the transitions in and out of art and everyday life. It’s similar to the way my thoughts move, slide, jump and overlap each other as I am walking.

I keep walking in anticipation of what the other windows along this street have to show me. The windows of an antique shop, with its eclectic array of objects neatly arranged on glass shelves, attracts me. A space in the centre of the shelves makes it possible to see into the depths of the shop, where the shopkeeper sits behind a counter. It looks cosy and the window display looks a like a hard version of my own window exhibition. While I have soft crocheted containers, sponges and doilies, here there are painted ceramic and wooden objects, glass and metal, some decorative, some functional, cluttered together creating a story of nostalgia and longing for the past. It is a world in itself.

The lines in the drawing I described distinguish between one thing and another, but lines are also used to create distinctions and categories, which need not be a bad thing, but they can also determine whether one thing is better or worse, higher or lower, than another. For example, fine art is considered higher than folk art or handicraft (even the name ‘fine art’ suggests this), novels are higher in the hierarchy than comic books, and of course the worse thing is when some people are regarded as more important or valuable than others. This is where I want to blurt out that this is all nonsense, and that maybe we should forget hierarchies. Jacques Rancière, together with the 19th century French teacher and educational philosopher Joseph Jacotot, claim that “all people are equally intelligent”.[31] Hah! Take that hierarchy! In his essay “The Emancipated Spectator” Rancière talks of the gap between teacher and pupil, actor and audience as something that people attempt to bridge, yet because of the initial problem of thinking of it as a gap, it is never possible.[32] The idea of bringing someone ‘up’ to your level of knowledge means you do not believe that you already are on the same level, and in the case of the teacher and the student that gap is precisely what defines the traditional teacher-student relationship. Is it possible that the more we look at and focus on the differences the deeper and wider the gulf becomes. Rancière and Jacotot also claim that equality is something that is “neither given nor claimed, it is practiced, it is verified”.[33] Do they mean ‘just do it’, as the slogan for a well-known sportswear brand encourages us to do? Jacotot and Rancière propose that equality is a departure point and not a destination [34] and I guess that means we should start living as if we are already equal. I believe that is how the people in the octopus’s garden are already living.

I could try to apply a different way of seeing to my octopus’s window and see, not objects, lamps, brushes, doilies, etc. but lines. I see the edges of the objects, the edge of the yellow doily is fuzzy and since it’s made of threads of woollen yarn my eye can follow either the edge or the in-and-out textured surface of the crocheting. From where I am standing I see that the doily is overlapped by a strange brush made from a used shampoo bottle and has bristles made from rope, the edge of the bottle is smooth and curves down to be interrupted by the lines of the wiggly rope, then it jumps to the line made by the rough edge of the pottery cup, which is intersected by the white dribble of glaze down the side that meets the short lines of cracks in the clay and glaze. These lines are joined by the dotted lines made by the rough texture of the clay as it protrudes through the glaze…there are so many different types of line on this one object. If I look for lines and allow my eye to run along them the objects recede and become surfaces and vessels for lines.[35]

The next window is that of a café. It’s closed and therefore dark inside but there are plenty of little lights, both in the window itself and deep within the café. As much as I can see, the décor is sumptuous and old-fashioned, with heavy drapes and tablecloths, candlesticks and decorations. I can’t really see in, but this only adds to the allure. Like the antique shop this is a view into another world, and I am reminded of Mr. Tumnus’ home as depicted in the film The Lion, the Witch and The Wardrobe.[36] Narnia, where Mr. Tumnus lives, is in another world quite different to our world and their homes and everyday objects have developed in a different way; they are unfamiliar, yet still recognisable. As an installation, this café would not be out of place in an art gallery or museum.

The fact that the streets are empty of people, that the cafés and restaurants are only serving takeaway food and drinks, that there are no tourists, and consequently there are increasingly less shops operating in the Old Town, only adds to the appeal of these windows. Shop windows, unlike the windows of a home, studio, office or factory or other workplaces, are specifically intended for us to look in. Shop owners want us to notice and to look, desire and ultimately want things enough to buy them. But these windows are different. There is less to see and buy, less to tempt and distract us, so I am free to just look, and look in whatever way I like and to imagine.

Having walked along the quiet empty street behind St. Nicholas’ church (now a museum and consequently closed), I come to a restaurant. It also has an installation in the window. It takes up quite a lot of room, but since there are no customers, this probably isn’t a problem. The installation is a table set for diners and has mannequins dressed in long flamboyant party dresses sitting around it. It’s a little surprising, a little over the top, but it creates a rich and enticing image. The lights are on and the restaurant is open. In the background, behind a counter, a well-lit waiter is folding napkins or polishing spoons or doing whatever waiters do when there are no customers. I usually look at art alone, so being the only one on the street looking in is quite appropriate. The waiter doesn’t appear to see me, and I continue to watch the folding or polishing or whatever they are doing. It’s like a performance and I am the audience.

Now, let’s imagine a game of football, but this game is a little different to normal football because the players, like our arguing octopuses, change sides during the game. They do this smoothly and unnoticeably and they may swap sides many times. Their allegiances, like those of the octopuses, change. In one moment, they are working hard to get the ball in one direction, but then the next they aim in the other direction towards the other goal. In a game like this the focus would shift away from the teams because the goals would be the winners or losers, and individual players could focus, not on winning or losing, but the game itself, on the beauty of the passes, the way the ball moves across the grass and the way the players manage to control the ball. It would also focus on teamwork, but it would be a completely different kind of teamwork to what we are used to. Playing exclusively for one team need not be the only way to play. Arguing for the other side, would not only be useful from the point of view of understanding and possible empathy, but it would also put the ideas, arguments and any resulting solutions centre stage, not the individuals (and their egos).

Not far from this restaurant is another art gallery.[37] There are spotlights aimed at clay mask-like pieces on the walls and at the far end of the gallery a well-lit wall and floor section of clay. In front of this stands a camera on a tripod. I think someone is making a film of the drying clay. I am a witness to process art. I keep walking. Around the corner there is a café with a bench and purple cushions squashed up against the window. I take a photo and then notice my own reflection on the glass. I watch it as I move back and forth changing the composition of the reflected image. The waiter was a performer in the restaurant and now here I am, also a performer or maybe a participant in participatory art.

I’m very close now to the Tallinn Art Hall. The exhibition in the Art Hall itself upstairs is not available to me because the windows are too high but the Art Hall Gallery on street level is well lit, and I can see the work in the front room.[38] There are paintings on the walls, but the most dominant part is a large pink wall painted to look like brickwork that is angled and takes up most of the space. This pink wall is echoed by a stack of what look like printed sheets of the same pink brickwork on the floor of the gallery.

One thing that windows do is equalise. I don’t mean in a way that makes things bland or all the same or indistinguishable, but it makes what is behind the glass a single entity. The individual objects are framed by the window, the frame, the windowsill and the glass. For example, the contrasts between the objects in my Octopus’s Garden of Silly Delights are lessened. The differences between the fuzzy hand-crocheted items adjacent to things made of wood and string or shiny plastic PET bottles, cut so the scissor marks are visible, are softened by the window. There is a sense that rather than looking at separate objects it’s like looking at a picture. There also tends to be one angle we look from and that too makes it like a painting. In a similar way, the fact that the galleries, shops and cafés are closed has an equalising affect, so that everything can more easily be looked at with the same eye or filter; in this case the eye is that of the viewer.

I walk home.

A couple of days later I again walk past the restaurant with the well-dressed mannequins and am shocked to see that they are headless. How did I miss that? I’m not shocked because they don’t have heads, but surprised that I didn’t notice this the first time. How could I be so unobservant? I call myself a visual artist and yet sometimes I don’t see things. What looked the other day like a playful installation with customer replacements in the form of those mannequins could now be interpreted to mean something far more sinister. Today, it is a completely different exhibition.

Art and artmaking is ever hopeful, like the optimistic pursuit of utopias. It’s also like walking, where we put one foot in front of the other taking, one step after another, the next work, the next drawing, the next text or article, the next application, even the next thought will be better than anything I have ever made or drawn or written or thought or walked before. I am always hopeful, otherwise I wouldn’t be doing this. One reason we might look to artists and the way they work is not because they are special (they’re no more special than anyone else) but because many of them know and have experienced the contradictions of living and working in a world where their work is both overvalued and undervalued, useful and useless, worth lots of money and worth nothing. There are times when I feel I have nothing to lose and feel quite bold, other times I want to play by different rules, or no rules at all. Being told something is impossible ignites me. Flexibility and fluidity and playing differently with different aims and expectations can be an asset. Let’s continue coming up with new worlds, new utopias, be they octopus’s gardens, fictitious worlds accessed through wardrobes, equality as prescribed by Jacotot and Ranciere, places where you can’t buy anything, unlikely football games or just different ways of looking at the world and art and non-art. Most importantly let’s not evaluate or decide too quickly whether any of our ‘silly’ utopian ideas are good, possible or practical, in the same way that we shouldn’t judge an artwork, performance or written work before it is finished. Let’s put these crazy ideas into practice and then with the cool observing eye of the anthropologist sitting high on her umpire’s chair watch and see what unfolds and happens next.

In

a world on the brink of ecological disaster;

a world coming to terms with a deadly virus;

a world where belligerent and inflammatory politics endeavours to entice and control us;

a world where big tech sees and knows more than we’d like;

a world where narcissism and lying seem to be accepted ways to behave;

I present to you

[12] Friedrich Nietzsche instructs us to “Sit as little as possible; do not believe any idea that was not born in the open air and of free movement — in which the muscles do not also revel”. He also wrote, “We [meaning himself] do not belong to those who have ideas only among books, when stimulated by books. It is our habit to think outdoors – walking, leaping, climbing, dancing, preferably on lonely mountains or near the sea even when the trails become thoughtful”. What a delightful image to imagine Nietzsche, a “serious” philosopher “leaping, climbing and dancing”! Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo / Complete Works, Volume Seventeen. (New York: Macmillan, 1911) <https://archive.org/details/TheCompleteWorksOfFriedrichNietzschevol.17-EcceHomo> [accessed 23 June 2020]

[13] Adrian Tchaikovsky, The Children of Ruin (London: Macmillan, 2019).

[14] There is much to learn from non-humans. I would like all creatures, living and non-living, to be on an equal footing, because as Rosi Braidotti repeatedly states, “We are in this together, but we are not the same”. Thinking as a Nomadic Subject lecture, Institute for Cultural Inquiry, Berlin, 7 Oct 2014,

<https://www.ici-berlin.org/events/rosi-braidotti/> [accessed 10 April, 2021]

[15] Rosi Braidotti, Nomadic subjects: embodiment and sexual difference in contemporary feminist theory (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994).

[16] Braidotti, p. 5.

[17] Braidotti, p. 25.

[18] Janet Wolff, ‘The Social Production of Art’ (London: McMillan, 1994) p.27. (citing Diana Laurenson, (ed), ‘The Writer and Society’ in The Sociology of Literature (London : Paladian, 1972) p.105–116.

[19] Hanna Guttorm, ‘Coming Slowly to Writing with the Earth, as an Earthling’, RUUKKU - Studies in Artistic Research,15 (2021) <https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/934067/934068> [accessed 16 June 2021]

[20] Henrik Rakitin, Laguna (Tallinn: 1. märts Gallery, 4.01–12.02.2021).

[21] Erki Kasemets, Karl Marx loomariigis / Karl Marx in the animal Kingdom (Tallinn: Draakon Gallery, 15.12.2020–30. 01.20).

[8] Ulvi Haagensen (and Aksel Haagensen), Octopus’s Garden of Silly Delights / Kaheksajala iluaed täis totakaid hõrgutisi (Tallinn: A-Gallery, 6.01–27.02.2021).

[11] An image inspired by the film Kitchen Stories, dir. by Bent Hamer, (BOB Film Sweden AB, Bulbul Films Svenksa Filminstitutet, 2003) where Swedish efficiency researchers come to study Norwegian men in the hope of optimizing their use of their kitchens.

[36] The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, dir. by Andrew Adamson (Walt Disney Pictures, Walden Media, 2005).

[37] Olesja Katšanovskaja-Münd, Hetkes olemise jäljed / Traces of Existence in a Moment (Tallinn City Gallery, 13.11.2020–17.01.2021).

[38] Benjamin Badock and Kaido Ole, Varblane peos / A Sparrow in the Hand (Tallinn: Art Hall Gallery 19.11–24.01.2021).

[9] Allan Kaprow, ‘The Happenings are Dead: Long Live the Happenings! (1966)’, in Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1993), p. 59.

[10] Allan Kaprow, ‘Performing Life (1979)’, in Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1993) p. 195.

[22] Hal Foster, ‘Culture Now: Hal Foster’, 2015. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Esm21k-zW_w&t=1304s> [accessed 15 March 2020]

[23] Viktor Shklovsky, ’Art as Device’ in Theory of Prose, trans. by Benjamin Sher (Dalkey Archive Press, 1991), <https://doubleoperative.files.wordpress.com/2009/12/art-as-device.pdf> [accessed 23 June 2021]

[24] Shklovsky, p. 6.

[25] Ben Ehrenreich, ‘Making Strange: On Victor Shklovsky’, in The Nation, 5 February 2013 [accessed from https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/making-strange-victor-shklovsky/]

[26] Mall Paris, Lõpmatus / Infinity (Tallinn: Hobusepea Gallery, 16.12.2020–01.01.2021).

[27] Sirja-Liisa Eelma, Postkaart viies pildis / Postcard in Five Stills (Tallinn: HOP Gallery, 18.12.2020–02.02.2021).

[28] Martin Farrer, ‘Calls to stop wealthier people ‘queue jumping’ Covid-19 vaccine jab wait list’, The Guardian, 11 December 2020 <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2020/dec/11/stop-queue-jumpers-drug-makers-urged-not-to-sell-covid-19-vaccine-privately-in-australia> [accessed 2 February 2021]

[29] Paula Erizanu, ‘Here in Europe’s poorest country we have no vaccine to argue over’, The Guardian, 28 January 2021< https://www.theguardian.com/world/commentisfree/2021/jan/28/here-in-europes-poorest-country-we-have-no-vaccine-to-argue-over> [accessed 2 February 2021]

[30] The lines fulfil multiple functions simultaneously, reminding me of Rosi Braidotti’s observation that “It is as if some experiences were reminiscent or evocative of others; this ability to flow from one set of experiences to another is a quality of interconnectedness that I value highly.” Braidotti, p.5.

[31] Kristin Ross, ‘Translator's Introduction’. The Ignorant Schoolmaster: Five Lessons in Intellectual Emancipation (California: Stanford University Press, 1991), p. xix.

[32] Jacques Rancière, ‘The Emancipated Spectator’ in The Emancipated Spectator (London: Verso, 2009).

[33] Ross, p. xxii.

[34] Ross, p. xix.

[35] These lines are like all the unseen lines that surround us in our everyday lives and I am reminded of Tim Ingold’s description of the environment around people as a “zone of entanglement”. Tim Ingold, 'Bindings against boundaries: Entanglements of life in an open world' in Environment and Planning A Vol. 40, Issue 8, 2008, pp. 1796–810.