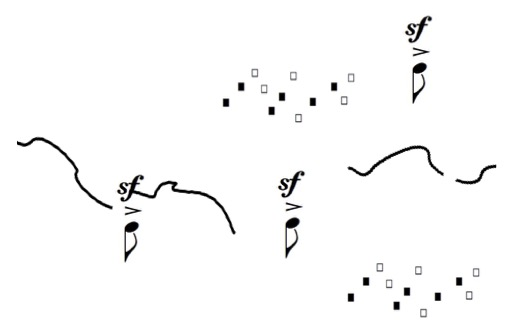

- Timbres — The uncertain, fragmentary beginning of this section gradually becomes more continuous and definite. Experiments with pure tone and breath tones, the intervening percussion and extended techniques led to a choice of fluctuating colours, and alternation between the hesitant and firm, the piercing and muted.

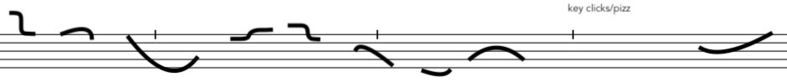

- Tonalities — The score here suggested a meandering, stepwise movement of pitched and unpitched runs through a wide pitch range.

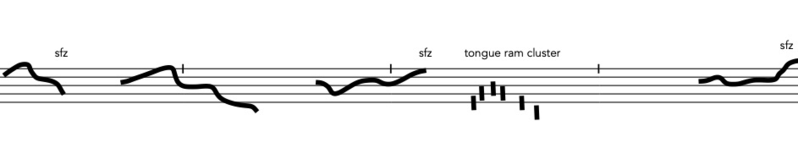

- Techniques and functionality — I chose normal and breath tone runs, interspersed with single and clustered tongue rams, half tones, pizzicato, phenomes, key clicks, flutters (open and closed), jet streams, trills, glissandi, and sforzandi. The microphone was essential to pick up the microsounds.

- Interpretative challenges — Conveying ambiguities, hesitance, agilities; becoming energized and driven. The shapes of the graphic notation directed technique decisions and flow.

- Transcription — The structures for this improvised section fundamentally followed the shaping given in the violin score, with flute techniques inserted, such as tongue ram clusters and percussion. I followed, and attempted to reflect, the text on the screen with tempo, volume and cascades of notes, incorporating a sense of multiplicity through rapid pitch changes and successive techniques.

Section 3:

Score notes: ‘Very static and quite dry’.

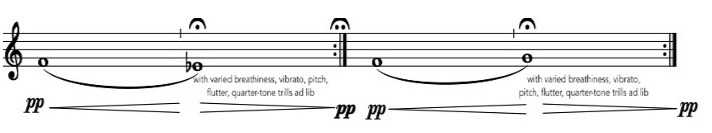

Violin score Flute transcription

- Timbres — A clear flute tone, at times shadowy, light, and dry worked best. I aimed for an emphasis on pianissimo and lightness, until the steadiness and firmness of the last gesture of ‘walking’ quavers.

- Tonalities — A rather static tonality, with gestures of repeated notes, trills, pizzicato and sustained notes. Pitches largely remained within the lower middle range of the alto (concert pitch B3 to F#5).

- Techniques and functionality — Much of this section includes harmonizer processing, better activated with clear flute tone. The screen becomes highly complex, with many juxtapositions of colour, shapes and text.

- Interpretative challenges — The harmonized repeated notes with interspersed sustained notes suggested alternating movement and stillness, somewhat flittery at times but more grounded within a space of multiple pitches and implied characters. Nothing is particularly direct. A feeling of floating, of anticipating something emerged, which became more focused with an increasing sense of familiarity (quotidian) towards the end of the section.

- Transcription — The notes of the violin score were transposed to fit the alto flute (down a 5th to match violin pitch).

Section 4:

Score notes: ‘Fast and furious, progressively more frantic, adding new material’

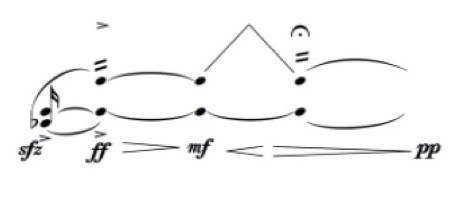

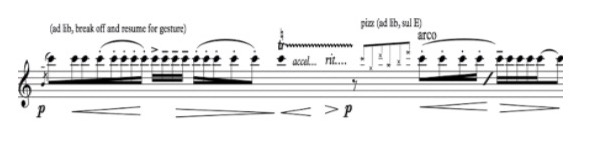

Violin score (opening gesture) Flute transcription

- Timbres — This section demanded a clear, intense tone, and a wide, frequently changing dynamic range.

- Tonalities — The fully notated gestures are often angular and clipped, over a wide and frequently changing pitch range.

- Techniques and functionality — Wide intervals, accents, ornaments, pizzicato, and flutter combine with rapid tempo and increasing textural complexity in the sounds and images.

- Interpretative challenges — The short, notated figures become increasingly frantic and entangled, amongst tumbles, collisions, and apparent disconnections. Devising the order of cells, repetitions and spacing focused on this build-up of freneticism, whilst a sense of connected lines needed to be gradually established and developed.

- Transcription — The violin notation was transposed to fit the alto flute.

Section 5:

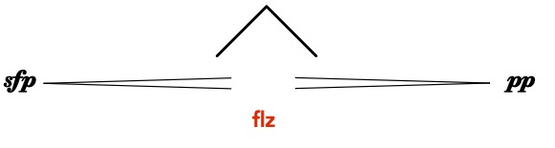

Score notes: ‘Slow, ritualistic’

Violin score Flute transcription

- Timbres — I experimented with timbres and pitches to reflect stability and a sense of ritual, aiming for an open, reflective, meditative tone and atmosphere with momentary flutters and fluctuation. A firmness of tone worked best and was clearly picked up by the computer actions.

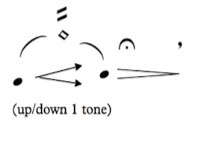

- Tonalities — This section consists of two-note phrases rising or falling by a tone, occasionally interrupted with varied breath techniques and changing to higher or lower pitches. Computer replay of these gestures created mild dissonance at times.

- Techniques and functionality — The long tones, flutter and alternative fingerings created sounds that worked well as triggers and were easily captured and replayed.

- Interpretative challenges — Serenity and composure was achieved through a steadiness of breath and attention to slow inhale/exhale actions. In this section, repetition invoked a sense of dwelling and knowledge of place, of familiarity and coming together.

- Transcription — This transcription involved pitch choices and timbral choices, as shown above.

Score notes:

‘Initially very fragmentary stepwise motion […] gradually add light pizz. groups, sforzandos’

Making Place is interactive, with sound-processing, text, and visual animations being generated by the performer’s instrumental sound. The score requests casually snapped photographs (5) and sound recordings (5) to insert into the program. Many field trips to the walk location occurred for this collection, as weather patterns and lockdown restrictions fluctuated. The walk itself is easy and repeated visiting kindled familiarity and an intense awareness of minutiae in this place, of invigorated listening and looking, of inhabiting and feeling. From a multitude of photos taken, final choices were based on colour definition and contrast that would prove most effective on the screen. Sounds were less evident, as there were few on this track since it meanders around through open grasslands, isolated forests, and abandoned or inexistent stations.

Of the five sound recording sources, the most elusive and capricious was the wind. The area around Ballarat is renowned for incessant wind, but on several occasions, there was almost none, on others it was so strong as to be unrecordable (in a ‘casual’ fashion). Finally, a beautiful mild wind occurred in the forest, appearing as gusts in the tops of the eucalypt trees, coming down towards us behind a small wooden shelter and passing into a huge pine tree before disappearing into nothing. The same pattern repeated and repeated, creating an intense feeling of place, that felt rather like in the centre of a carefully spatialized electroacoustic performance! Birds were sometimes plentiful in the forest, and sometimes absent. Parrots and even golden whistlers were seen and heard, but kookaburras and magpies dominated the scene with their distinct and sometimes raucous calls. Frogs, footsteps, and the gate completed the recordings, encompassing sounds from the start, middle and end of the track.

Back at home, listening to the recordings recalled the vibrancy and intensity felt in the space. The forest birds so familiar and so beautifully resonant; the dense and incessant call of the frogs only heard in the grassland swamps; the relentlessness of the footsteps suggesting isolated human movement on the track; the latch and creaks of the gate recalling wide-open fields; the shifts of the wind as it changed velocity, potency, and direction. The transferal of environmental sound to digital media emphasized the ‘ephemeral and volatile character of a soundscape’ (Bass and Rebelo 2014), through a clarity of sonic articulation, a distillation of location ambience. Each sound began to influence my approach to the piece, to invite new sonic effects, and to modify my ideas of the improvisations.

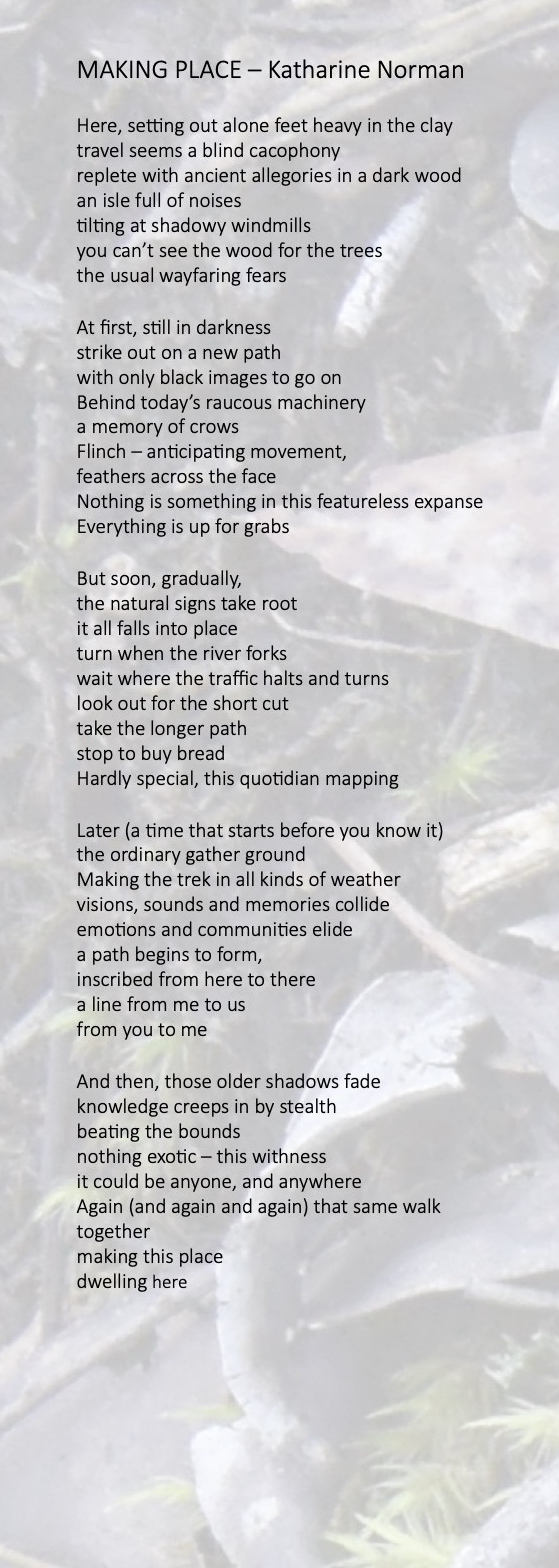

The poem’s five stanzas correspond with the five sections of the score. Norman’s evocative text takes us through an imaginary, yet highly recognizable walking experience filled with shadows, sounds, feelings, shifting images, and memory triggers. It appears on the screen line by line in a variety of forms as the piece progresses. I already know this text, but now I am applying it to a different space and different connections begin to appear. Through the poem I am now imagining the walk in a familiar place, in the Australian countryside, emphasizing the centrality of the quotidian. It describes a place I want to be, feelings I have felt many times, associations that spike the imagination within an undulating and compelling flow. My interpretation and place making was driven by this text as words and meanings became sources for notations, techniques choices, and sonorities in the live flute part. These sounds, in turn, gradually formed and vivified this feeling of a place comprising multiple entities and sensations.

The instrumental score was initially written by Norman for piano in 2013, and a version for solo violin was later written by Norman in 2015. The similarity of range and capabilities of violin and flute meant that I chose to base my flute score on the violin version, with reference to the piano part and sound. Significant changes were made in some sections (for example, in Section 1 where pitch changes, and breath and tongue techniques reflected flutistic capabilities), and simple transpositions were made in others (for example, in much of Section 3). In each case, the instrumental sound effects and sonorities were crucial to decisions.

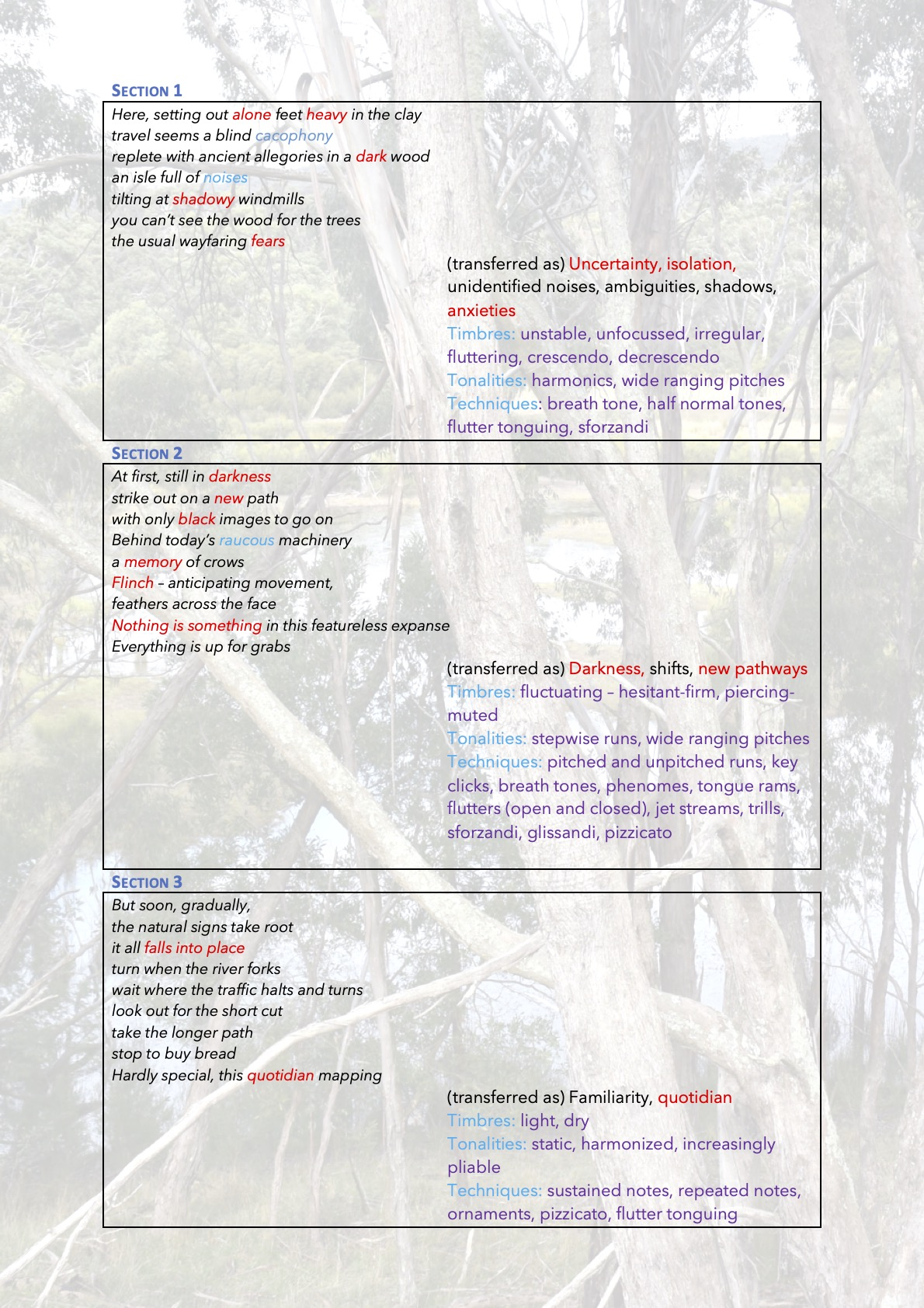

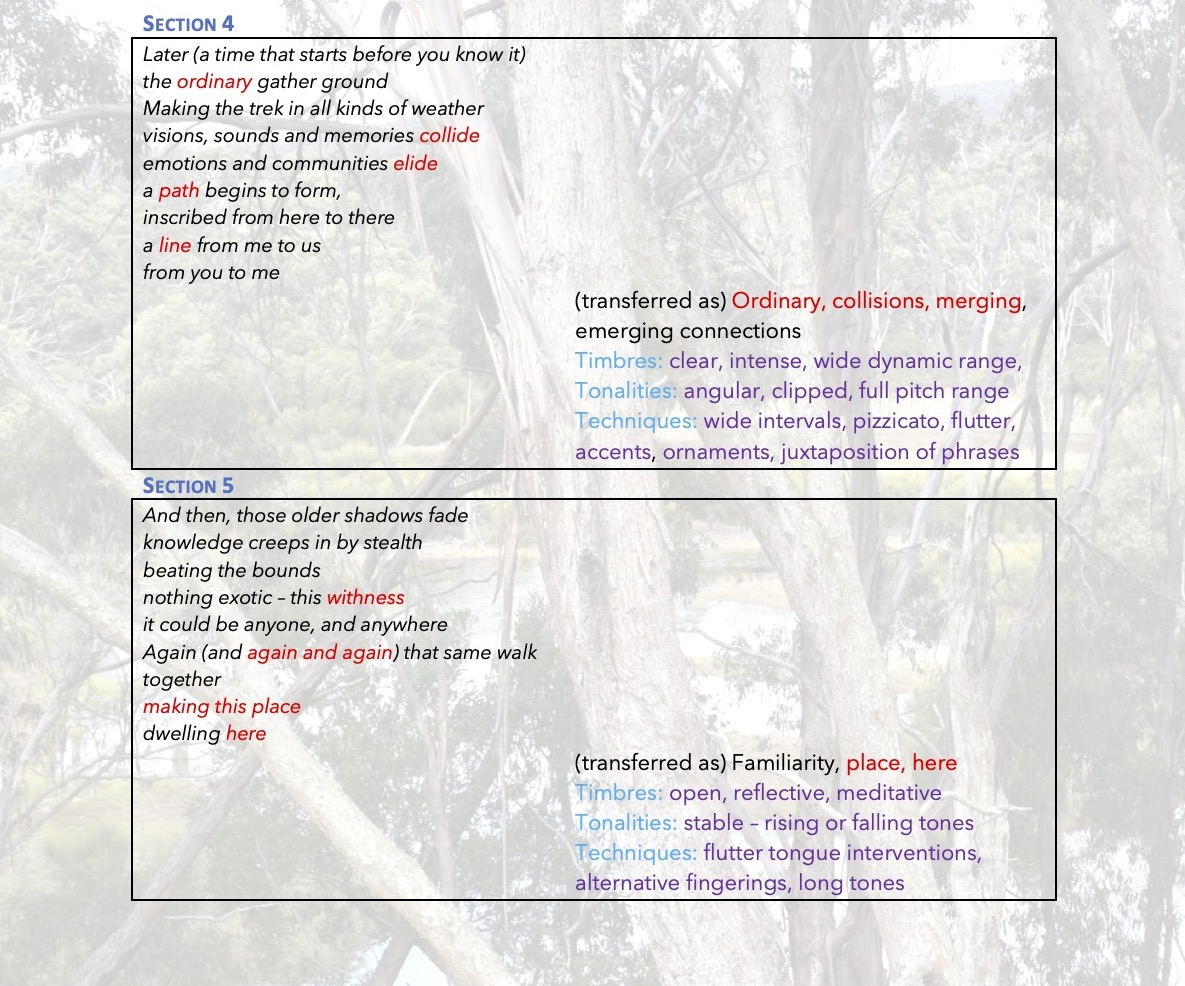

As I began to re-interpret the score for alto flute, four main elements emerged as problematic content to explore: timbre, tonalities, techniques, and functionality with the screen and software. These categories were applied to experimental notation and improvisation procedures. Further questions related to interpretation of the work, extracting meaning from the text, the sound and image processing, and understanding the positioning of the flute. Defining the links between the text and musical choices became critical in these initial stages. In a visual representation (see below), I traced my responses to text as they might translate into the music. Red text in the poem is used for ‘key words’ that signify mood or character, blue text is for sound references, purple text is for playing ideas/aesthetic realization, and green signifies quotidian and resolution.

Having revealed these relationships, experimentation with various options for each section occurred. I searched for timbres to reflect the text, tonalities that related to the score notation, techniques reflective of an apposite aesthetic, and interactive functionality that allowed the piece to operate. Examples of outcomes follow, showing excerpts of score instructions, violin notation, transcribed flute notation, and comments on process.

- Timbres — Experiments with breath tone gestures, harmonics, still, and interrupted sonorities, closed and open embouchure flutter tonguing, and various volume levels. All of these were used at various times, creating discrete gestures across the section.

- Tonalities — Use of varied pitches, harmonic sweeps, multiphonics.

- Techniques and functionality — Experiments with focused tone and breath tone, combinations of pure tone harmonics. The microphone proved essential to activate the screen.

- Interpretative challenges — Developing shadowed, veiled gestures that acquire strength (monolithic character) from tonal and timbral interventions; engaging with soundscape as layers of sounds built up and faded away.

- Transcription — Finding these ‘monolithic events’ proved to be quite difficult. The piano plays huge, loud chords and the violin plays idiomatic double-stopped gestures. Experimenting around on the flute I looked for gestures of equal strength, finally choosing a variety of harmonics, multiphonics, breath tones and effects such as flutter tonguing. Adding reverberation gave these a significant resonance and intensity. I discovered that pure tone, rather than breath or fluttering tone triggered sharper screen imaging and animation. As the texture was built up with capturing and replay of flute gestures this became less important, and some more veiled sounds could be incorporated. The notated gesture seen above was freely modified in these ways in response to what was happening in the electronics throughout the section.

- Timbres — The uncertain, fragmentary beginning of this section gradually becomes more continuous and definite. Experiments with pure tone and breath tones, the intervening percussion and extended techniques led to a choice of fluctuating colours, and alternation between the hesitant and firm, the piercing and muted.

- Tonalities — The score here suggested a meandering, stepwise movement of pitched and unpitched runs through a wide pitch range.

- Techniques and functionality — I chose normal and breath tone runs, interspersed with single and clustered tongue rams, half tones, pizzicato, phenomes, key clicks, flutters (open and closed), jet streams, trills, glissandi, and sforzandi. The microphone was essential to pick up the microsounds.

- Interpretative challenges — Conveying ambiguities, hesitance, agilities; becoming energized and driven. The shapes of the graphic notation directed technique decisions and flow.

- Transcription — The structures for this improvised section fundamentally followed the shaping given in the violin score, with flute techniques inserted, such as tongue ram clusters and percussion. I followed, and attempted to reflect, the text on the screen with tempo, volume and cascades of notes, incorporating a sense of multiplicity through rapid pitch changes and successive techniques.

- Timbres — A clear flute tone, at times shadowy, light, and dry worked best. I aimed for an emphasis on pianissimo and lightness, until the steadiness and firmness of the last gesture of ‘walking’ quavers.

- Tonalities — A rather static tonality, with gestures of repeated notes, trills, pizzicato and sustained notes. Pitches largely remained within the lower middle range of the alto (concert pitch B3 to F#5).

- Techniques and functionality — Much of this section includes harmonizer processing, better activated with clear flute tone. The screen becomes highly complex, with many juxtapositions of colour, shapes and text.

- Interpretative challenges — The harmonized repeated notes with interspersed sustained notes suggested alternating movement and stillness, somewhat flittery at times but more grounded within a space of multiple pitches and implied characters. Nothing is particularly direct. A feeling of floating, of anticipating something emerged, which became more focused with an increasing sense of familiarity (quotidian) towards the end of the section.

- Transcription — The notes of the violin score were transposed to fit the alto flute (down a 5th to match violin pitch).

- Timbres — This section demanded a clear, intense tone, and a wide, frequently changing dynamic range.

- Tonalities — The fully notated gestures are often angular and clipped, over a wide and frequently changing pitch range.

- Techniques and functionality — Wide intervals, accents, ornaments, pizzicato, and flutter combine with rapid tempo and increasing textural complexity in the sounds and images.

- Interpretative challenges — The short, notated figures become increasingly frantic and entangled, amongst tumbles, collisions, and apparent disconnections. Devising the order of cells, repetitions and spacing focused on this build-up of freneticism, whilst a sense of connected lines needed to be gradually established and developed.

- Transcription — The violin notation was transposed to fit the alto flute.

- Timbres — I experimented with timbres and pitches to reflect stability and a sense of ritual, aiming for an open, reflective, meditative tone and atmosphere with momentary flutters and fluctuation. A firmness of tone worked best and was clearly picked up by the computer actions.

- Tonalities — This section consists of two-note phrases rising or falling by a tone, occasionally interrupted with varied breath techniques and changing to higher or lower pitches. Computer replay of these gestures created mild dissonance at times.

- Techniques and functionality — The long tones, flutter and alternative fingerings created sounds that worked well as triggers and were easily captured and replayed.

- Interpretative challenges — Serenity and composure was achieved through a steadiness of breath and attention to slow inhale/exhale actions. In this section, repetition invoked a sense of dwelling and knowledge of place, of familiarity and coming together.

- Transcription — This transcription involved pitch choices and timbral choices, as shown above.

The above notation-based enquiries combined in reality with early rehearsal processes and, as ideas became more clearly defined, rehearsals with the electronics began. These sessions highlighted transformations created by real-time electronics, in particular, the sonic alterations and activation of recorded sounds and live flute sound. The images were shown on the screen with varying intensity through the piece, activated by both my live flute sound and the software; the recorded sounds, processed and activated by the software, gradually became embedded in my response to the piece, as dialogue and convergence. The proportions of the piece are actually controlled by the computer system. The performer’s input as trigger to sounds and image animation allows the piece to progress, but the text gives the cues for when to move on throughout and tempos are arranged around this. The following overview shows phases of performance preparation as they occurred sequentially, the trials and choices of material and functionality, as the ‘place’ of Making Place gradually took shape. Of course, this process was cyclical, with reviews and adjustments occurring throughout.

(i) Interpreting and clarifying notation: choosing alto flute.

The choice of alto flute was partly to differentiate this version from my first (for concert flute), but also to explore a different range of colours and techniques characteristic of this instrument. Considerable time was spent exploring the distinctive tonal possibilities of each section, and the impact of these on interpretation. Notation was developed that accentuated the rich lowness of the alto, the easy and flexible production of breath sounds and percussion, and the varieties of overtones and harmonics present in the sound. The opening, for example, became quite static, with notes incorporating various amounts of airiness, vibrato and articulations that were intended to heighten the sense of setting out, of uncertainty, and shadowiness. The improvisatory pathways of section two were projected as hesitant but increasingly rushed, with a focused tone broken up by the more ambiguous sounds of muffled articulations, key clicks, tongue rams, trills, and tremolos. The visual effect of the lines on the score strongly influenced the running passages of this section, prompting speed and disruptions throughout. As the following composed section was transposed to fit the alto, priorities of articulation (more tenuto), and duration (a broadening and sense of spaciousness and, at times, heaviness) arose. The composed gestures of section four can be played in any order, with optional repeats at the performer’s discretion. The tone and motion of the alto here seemed to add a rather scuttling sense to these short, harried motifs, and an awkwardness in the quick register and dynamic changes. I chose to emphasize this characteristic, particularly later in combination with the computer capturing and replay. The final meditative section of repeated pairs of notes sometimes suggested unstable pitches and sometimes a firmness of tone that hinted at a peaceful resolution. Gentle dissonances created through the electronics signified this coming together of disparate parts. Low pitch choices and slow inhale/exhale motions added to this sensation of serenity and revelation of an awareness of place.

(ii) Working with the electronics: an intermingling of recorded sounds, images, text, and live flute

The electronics in this work consist of a system that activates screen images and sounds through live interactive processing of animation, text, and audio. The music score can be adapted for any instrument/s, and a 64-bit Mac OSX app can be pre-loaded with the performer’s field recordings and images. Performers are encouraged to use quickly snapped photographs and informally recorded sounds from the environment of a familiar walk. The performance instructions state:

The piece is interactive, in that the performer’s actions influence and in many cases trigger texts and other visual animations. These in turn influence the left/right panning of various sounds or sound processing, and when sound processing is switched on or changed. Audio ‘triggers’ from the performer are through amplitude (volume) levels and none are defined by pitch. There is no need to try and co-ordinate with or respond to audio processing in any ‘direct’ manner. More often it’s a case of building textures by varying materials and increasing or decreasing your activity — in particular in sections 2 and 4 of the piece (Norman 2017).

In rehearsals, my position as co-creator and performer merged as I became familiar with the workings of the interactivity and the need to trigger electronic effects with the playing. I used both a stand microphone and headset microphone, which worked well for a variety of effects. My sound technologist and I worked together to achieve improved transitions and balance, dealing with contingencies as they arose, most often with software vagaries (for example, simultaneous recording, playing, activating, and processing of sound). Successful pick-up of the flute sounds was dependent on choices of dynamics and tone qualities, and physical positioning — for example, pizzicato and tongue rams required very close microphone, while sustained notes or clusters of harmonics more space and resonance. The strength of sforzandi in the meandering pathways of Section 2 also became essential elements to progress the piece, and the increasing complexities and loudness of Section 4 propelled the screen into a frenzy of colour and text. Refinement of physicality and tonal projection concurrently increased awareness of the intensity and moderation of the live flute sound and various kinds of tension and path-turning through the piece.

The intermittent presence of pre-recorded sounds activated with seeming randomness, created a certain tension, a mimesis, perhaps, that provoked memories of walks, and memories of place. At times these seemed to enact a dialogue with the playing, at others they created an ambience or sensation that transferred to the playing, and sometimes they seemed to sit outside, creating a layer of their own. The opening would sometimes play the frog calls, at other times the footsteps, birds or wind; in the performance it happened to be the wind and gate noises that started the piece. Each time a different atmosphere seemed to be set, emphasized by the poetic text and equally random visual effects of the processed photos. I found that I chose the sound units of Section 1 to reflect the way the piece started, choosing strong but quite static notes, at times interrupted by flutter, wide vibrato, harmonic swings, or breath tones, depending on the intensity of the capture and replay of the live flute occurring at the time. The insistent frog calls heard in Section 2 provoked an increasingly frenetic mood that reflected the anxiety of the darkness and uncertainties of the text. Timbral changes to the live flute sound, capturing and replaying at various pitches, and the harmonics generated in Section 3 implied multiple presences, dialogues with the invisible, and inhabited but unpredictable surroundings. This sense of dialogue drew out a preference for a more delicate tone, softly disappearing sustained tones and spikily articulated pianissimo notes. The sound of the kookaburras in this section felt a little disturbing, adding, to me, a sense of the outside, a different view.

The photographs were unrecognizable as the ‘things’ I had photographed (until the end section), as they were transformed into beautiful colours and animated abstract shapes. I became immersed in this audio-visual world, a space of indefinite responses and surprising entities, driven on by the text and changing images and shapes. I found that there was a ‘turning towards the inside’, an intimacy that was expressed through breath, tempi, and sonorities reflective of the changing spaces and places of the walk. When the images appeared as stills towards the end of Section 5, I strove for a meditative, ritualistic mood with the repeated breath-like pairs of notes, themselves captured and replayed at various pitches, creating in me a compelling connection to place and feelings of understanding and arrival.

(iii) Rehearsing the performance

Having assembled the work, rehearsed, and explored performance ideas, a personal vision of the piece had emerged. Diverse elements felt assimilated into the journey, and rehearsals now worked to develop flow, anticipating the emergence of ecstasis. Moving from notated sections to improvised sections developed a natural flow, eased by a sense of freedom in interpretation and enjoyment in the playing. Uppermost in my mind was the practising of the epoché — the feeling of ‘doing’; attending to awareness in the moment, what I see, hear, feel, and do in performance. In situating the performance as an epoché exemplar my aim was to consider it with a certain amount of pre-reflective objectivity, aligned to Merleau-Ponty’s notion that ‘reflection is distancing or objectifying sensation and confronting it’ (Merleau-Ponty 2009: 280). I did not wish to over-practise this. I wanted to transition to performance sensations through the flow of musical material, whilst imagining how to keep the event separated. These short sessions became something of a mind-game as I stepped outside the habitual rehearsal frame, where connections of experience and sensations seemed to exist on a different sphere, and observation moved to a more external perspective. Surprisingly, I found the beginnings of an intense clarity in this, one that I hoped would emerge fully with the actual performance.

Next page| The Epoché