INTRODUCTION

As a key figure in the development of spectral music, Tristan Murail counts amongst the most influential postwar composers in the Western classical tradition. Tellur (1977) for solo guitar is an altogether unique work in his catalogue. In view of Murail’s rather traditionalist conception of musical authorship, its combination of open intabulated notation and unusual playing techniques implies a remarkable dependency on the performer’s individual heuristics and discretion.

With this exposition, I aim to shed light on the functioning of Murail's traditional authorship through my own performance of Tellur. Its structure is inspired by elements of Goehr’s (1992) historical analysis of the work-concept. One of the developments Goehr (1992: 226, 231) associates with the establishment of the work as a regulative concept around 1800, is the separation of the composer from the performance of their music. This created two seemingly opposite necessities: a necessity for abstraction of the instrument and at the same time a necessity for an adequate realization of the work (Werktreue).

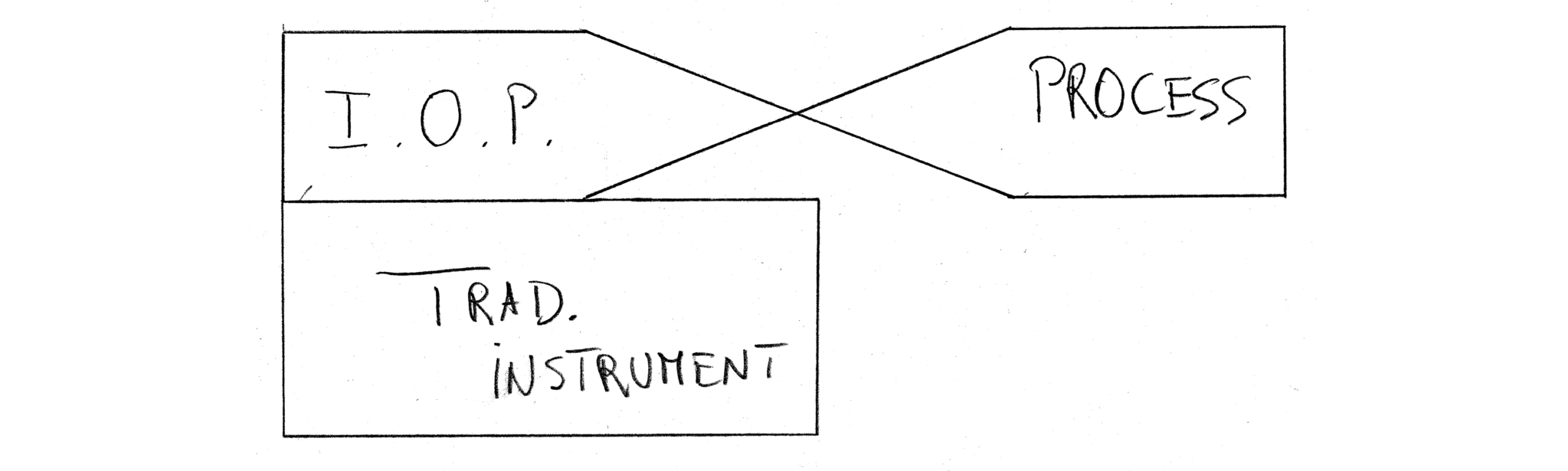

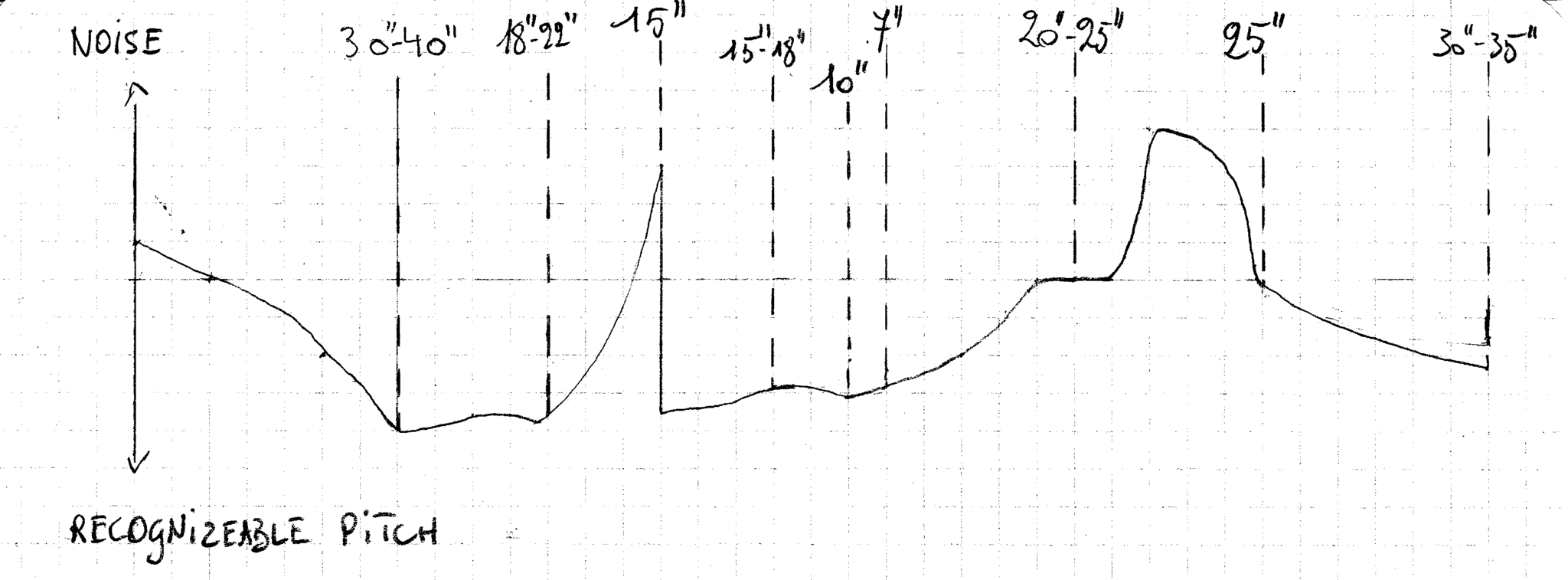

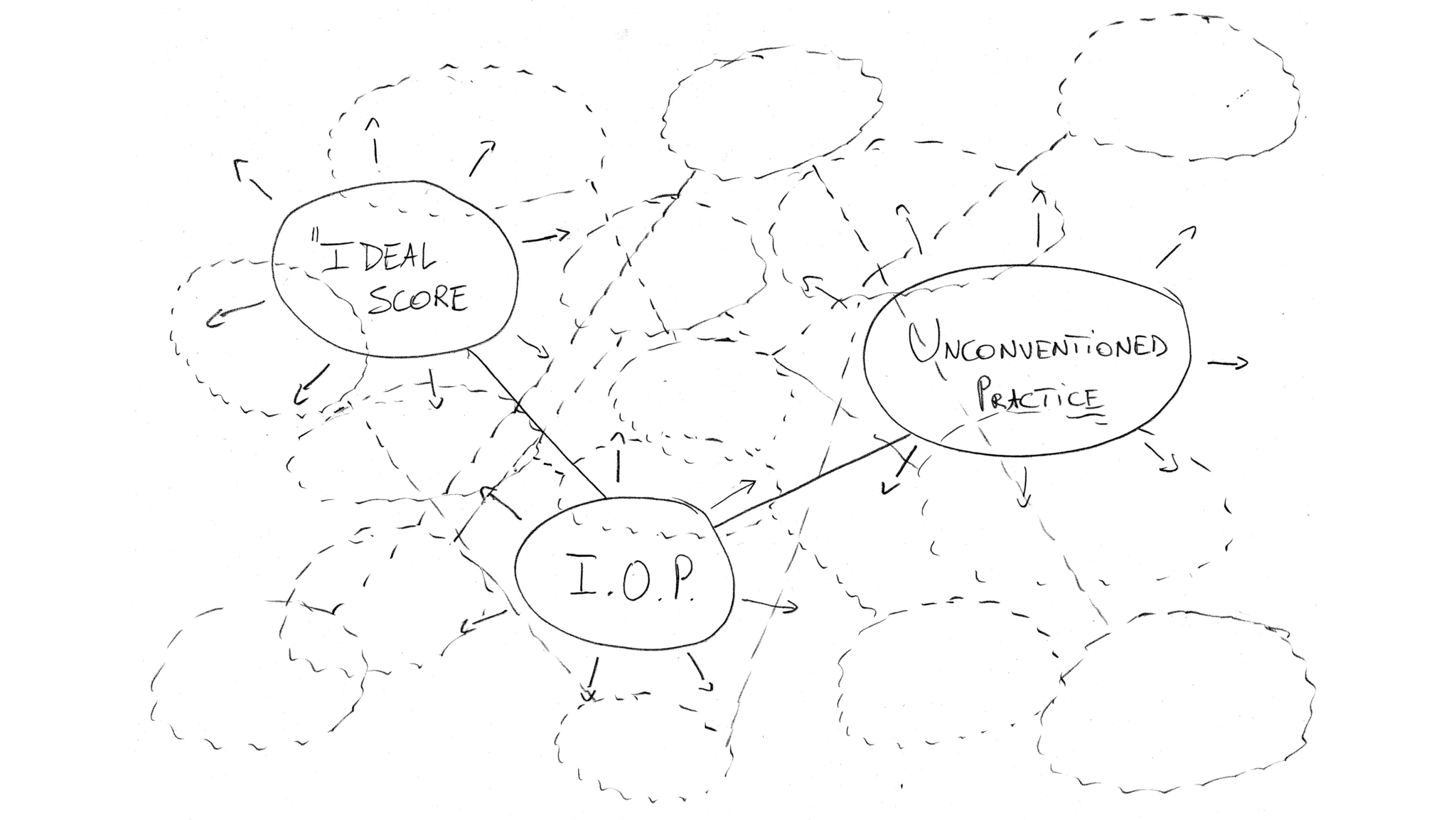

In the first part of this exposition, I use the work of Pierre Schaeffer as a point of reference to analyze the abstraction of the musical instrument in Murail’s compositional language. The insights gained from this broader analysis then inform the second part: an engagement with Murail’s ideas on authorship, namely with his concept of the ‘ideal score’. I apply this concept to the case of Tellur through historical situation and theoretical analysis. In the third part, I apply insights developed in previous parts to analyze the issue of Tellur’s ‘adequate’ realization within a performance practice that lacks functioning conventions.

At first glance, the successive parts (one to three) lead stepwise from theory to practice, reflecting a traditional paradigm long common in performance studies.[1] However, in part three, the concept of the heterotopia of the practice room opens the door to a reversal, and the movement between theory and practice becomes bidirectional.

As will become clear near the conclusion of the exposition, this narrative structure is meant to reflect the creative dynamics of the heterotopia of the practice room itself. It reflects the methodical structure of the creative process that led to my renditions of Tellur. As a consequence – and contrary to traditional academic norms – the exposition thus purposefully demonstrates a methodology before summarizing it.

A second consequence is that, as the scope of this project unfolds gradually, so do the different claims for its contribution to the fields it engages with. The two linchpins of this contribution are: 1) the recording presented on this front page (at least I hope it will be received as such); and 2) the framework of the heterotopia of the practice room itself, which crystallizes at the end of the exposition and helps illuminate some of the ‘novel’ creative decisions in the development of my rendition. On the trajectory between these two points lie two other contributions: a diagnosis of the fundamental tension between the musical thoughts of Murail and Schaeffer (in part one); and a detailed theoretical analysis that presents Tellur’s structure as a multiplication of processes (in part two).

A third consequence is specifically related to the bidirectional movement between theory and practice. This bidirectionality implies that all elements in this exposition that would traditionally be classified under musicology are at their base inextricably tied up with my experimentation on the guitar. The maxim that in artistic research there is no such thing as a-practical theory and a-theoretical practice applies to an extreme degree here, and I consider all of this publication a representation of my artistic practice.

And finally, a disclaimer: because this exposition both adheres to and subverts a traditional approach to the musical work, it both acts out deference to ‘the composer’ and, at the same time, undermines its originary authority. To allow for this ambiguity, I approach the composer like Foucault (1998) does the author: figuratively dead, but functioning. In other words, I do not claim to divine the ‘true’ intentions of the composer as a historic individual, nor do I ignore the composer altogether. Rather I look at how Tellur’s composer functions through the power relations of classical music practice.