Introduction

A station in the aesthetics of art is Edward Munch's The Scream (1893-1910). In a way it expresses completely the historical and aesthetic path of its social, political and artistic frame. "There is no God now, no tradition, no habits or customs – just poor man in a moment of existential crisis, facing a universe he doesn’t understand and can only relate to in a feeling of panic. [...] This is what distinguishes modern man from post-Renaissance history up until that moment: this feeling that we have lost all the anchors that bind us to the world"1. The Scream contains the human voice, but the work as a painting is silent. Then: How is this scream translated in music?

"In almost all of Wagner’s mature operas, situation arises in which a character screams”2.

In Strauss’s Elektra, offstage screams are heard during Klytämnestra’s death.

In Schoenberg’s music, the scream “transformed into a most important aspect of the vocal technique” of Sprechstimme3.

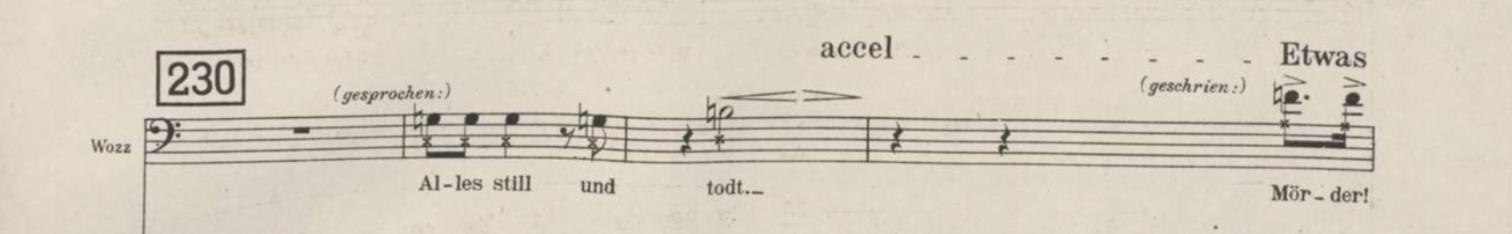

In Berg's Wozzeck (1925), the antihero screams to himself "Mörder" ("murderer") when he realises that he killed his wife.

In the throe of the 20th century, the melodic vocal lines were no more ends in themselves. Beauty was not only found in the Folk Voice, but also through “non-musical sounds”. Saturation was to be more and more appreciated4, affecting and "devaluing" the Italian bel canto, contributing at the same time to the use and development of new techniques.

"The term extended vocal techniques was coined during the 1960s' to delineate vocal techniques beyond established Western singing practices, especially bel canto"5.

Innovative artistic movements during the 20th century, mainly in the field of literature, acted as precursors of the deliberate musical use of a wider spectrum of vocal sounds. Main components that initially gave the space for experimentation were the text, its visual structure - in other words the score - and the performer himself/herself. Both, extended vocal techniques and performance art are traced back to futurism, dadaism and lettrism6.

The Precursors

Futurism: Filippo Tomaso Marinetti Zang Tumb Tumb (1914)

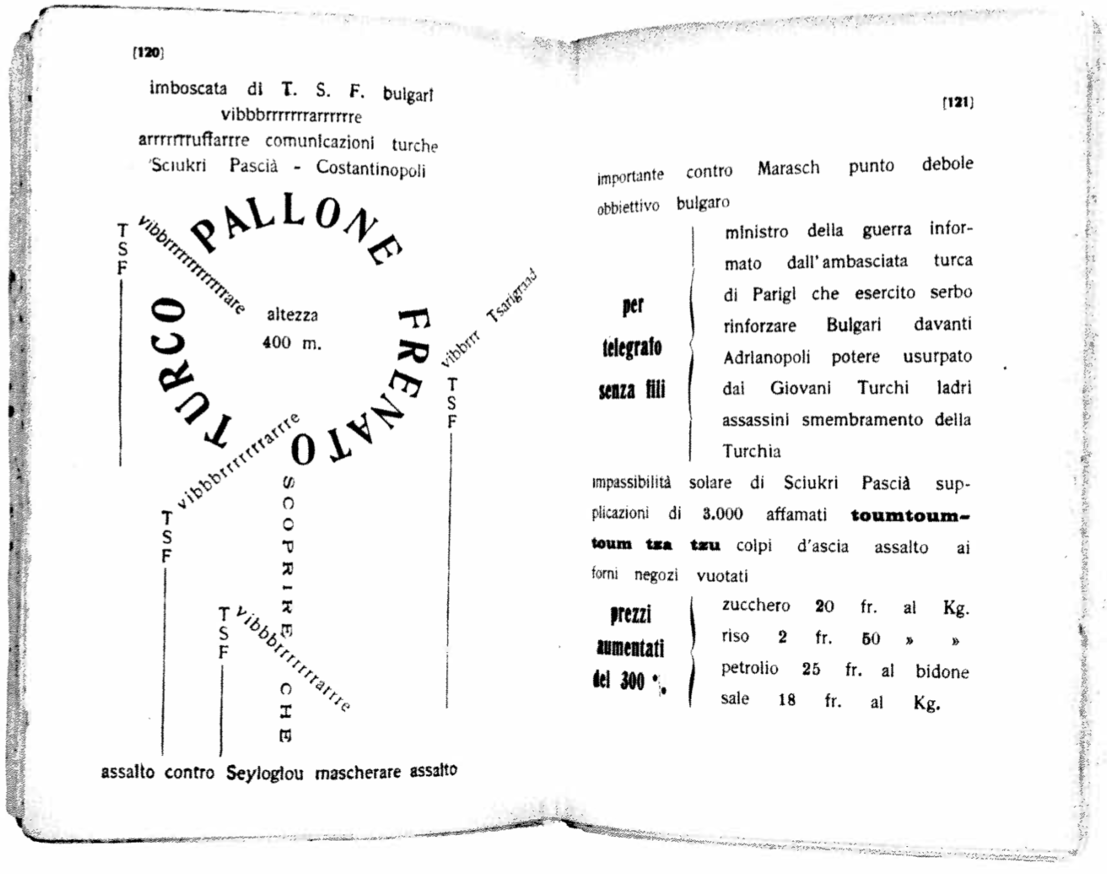

Between the years 1912-1914 in Italy, the writer, poet, theorist and founder of Futurism, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944), published an innovative form of verbal and visual poetry. The work/novel Zang Tumb Tumb, is one of the most important early examples of sound poetry.

The poem narrates “the story of the siege by the Bulgarians of Turkish Adrianople in the Balkan War, which Marinetti had witnessed as a war reporter. The dynamic rhythms and onomatopoetic possibilities that the new form offered were made even more effective through the revolutionary use of different typefaces, forms and graphic arrangements and sizes that became a distinctive part of Futurism. […] As an extended sound poem it stands as one of the monuments of experimental literature with its telegraphic barrage of nouns, colours, exclamations and directions pouring out in the screeching of trains, the rat-a-tat-tat of gunfire, and the clatter of telegraphic messages”7.

The visual structure translated into sounds and the recitation of the poet highlighted the musical aspect of language, creating this way a bridge between literacy, musical composition and an early attempt of performance.

Dadaism: Kurt Schwitters Ursonate (1922-1932;)

Dadaists were questioning the role of art, its relation to nature and its non-sense, reacting to the social and political upheavals. In Germany, the forty-minute phonetic poem developed during a decade by the artist Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948), was to be of a great importance. Ursonate (1922-1932;) was between pure sound and articulated language8.

Kurt Schwitters was acknowledged as the founder of performance art, touring and performing his own works around Europe9. His poetic/musical work consisted of four parts: rondo, largo, scherzo and presto with cadenza. Schwitters commented: “I do no more than offer a possibility for a solo voice with maybe not much imagination. […] As with any printed music, many interpretations are possible. As with any other reading, correct reading requires the use of imagination10. [...] Consistent poetry is made of letters. Letters have no idea. Letters as such have no sound, they offer only tonal possibilities, to be valuated by the performer. The consistent poem weighs the value of both letters and groups”11.

Schwitters, developing the idea of futurists, invented a sound poem with non-existent words, which was related to music as a structured combination of pitches, vowels, consonants and rhythms.

Lettrism : Jean - Isidore Isou

The turn to the screams as an element of beauty and the use of extended vocal sounds came with Lettrism in France, around 1945. The movement's founder, Romanian immigrant theorist, poet, novelist, dramaturge, film director and visual artist Isidore Isou, proposed a new conception of poetry entirely reduced to the letter while understating all semantics. New letters, sounds and works did not carry any meaning, but were created only for the sake of Art.

“By focusing on the sound and the visual dimension of the words, the lettrists expanded their movement through hypergraphs, in which artists used not only Latin letters, but all known alphabets and signs, as well as invented symbols. […] Lettrism is an engine of interstitial transformation of the word and the letter, using a full radicalism in the field of acoustic experimentation through the use of nonverbal sounds of human production such as coughing or sneezing”12.

Lettrists' poetry was considered also vocal music with a rejected notion of pitch.“New” sounds or letters, voice distortion, different kind of screams, noise combinations and any sounds that the human body can produce anticipated the future movements of performance art. In relation to music: “This new song is based on the spontaneous and natural human voice, opposite to the expressive singing of popular or emphatic music of lyric singing. Moreover, its original subject matter, which is the letter, is embed in poetry”13.

Berg's indication "geschrien"("screamed") on bar 233 of Act III, Scene IV.

Wozzeck realises he killed his wife and screams "Murderer to himself" .

Techniques in the music of the movie and the interview:

different kind of screams in various ranges, heavy breathing, coughing, nasal sounds, tongue click, muting sound with hands, throat guttural and lips sounds,

Wagner's indication "schreiend" ("screaming")in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Act II, Scene IV.

A neighbor screams after David attacks Beckmesser.

Interview with Isidore Isou

Fragment from the documentary film Around the World with Orson Welles (St. Germain des Pres, 1955).

Explains and presents how Lettrtists created and used the new sounds they included in their poetry and performance.

Kurt Schwitters performing Ursonate,(05/06/1932, Frankfurt)

innovative vocal techniques in the sound poem:

- use of pitch and its constant change

- heavy use of consonants

- tongue trills

- falsetto

- use of rhythmical motives

- consciously structured musical phrases

Filippo Marinetti narrating.

Innovative vocal techniques in the sound poem:

- imitation of bombs' sounds

- extreme tempo of recitation

- heavy use of consonants

- whisper

- laughter using falsetto

- tongue trills

- throat sounds similar to whimper