Hanne Rekdal, flute

Kristine Tjøgersen, bass clarinet

Eira Bjørnstad Foss, violin

Tove Margrethe Erikstad, cello

Premiere recording, Bruket,

Periferien, Oslo 03.04.2019

Watch Lambert, Lambert! here:

Performed by:

Natali Abrahamsen Garner

Ditte Marie Bræin

Halvor Festervoll Melien

Norwegian Academy of Music, Oslo 01.10.2021

Director and scenography:

Tormod Lindgren

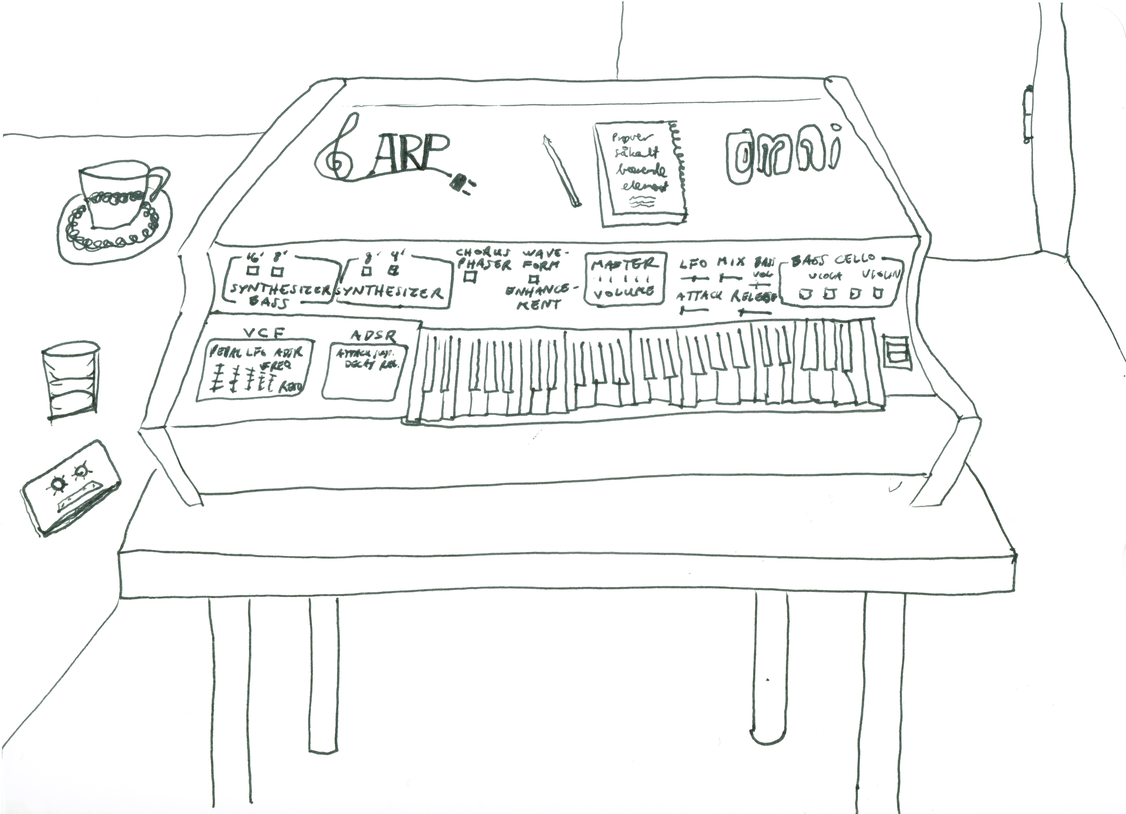

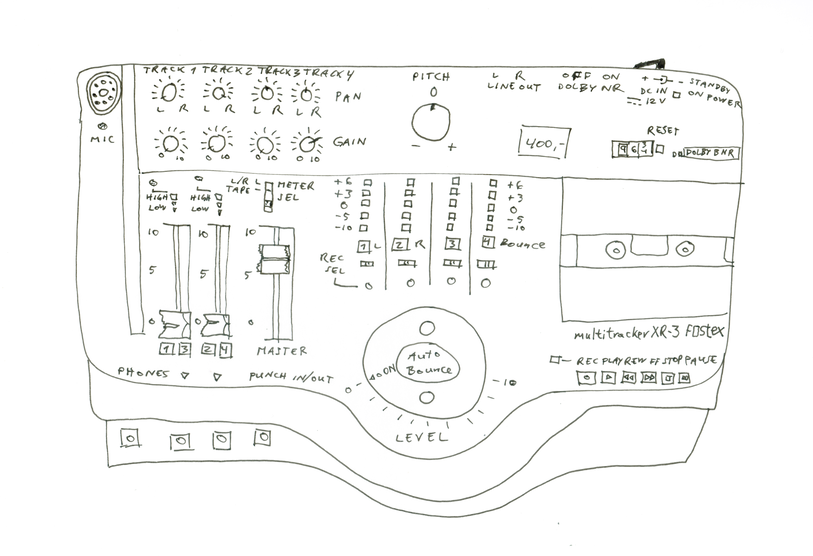

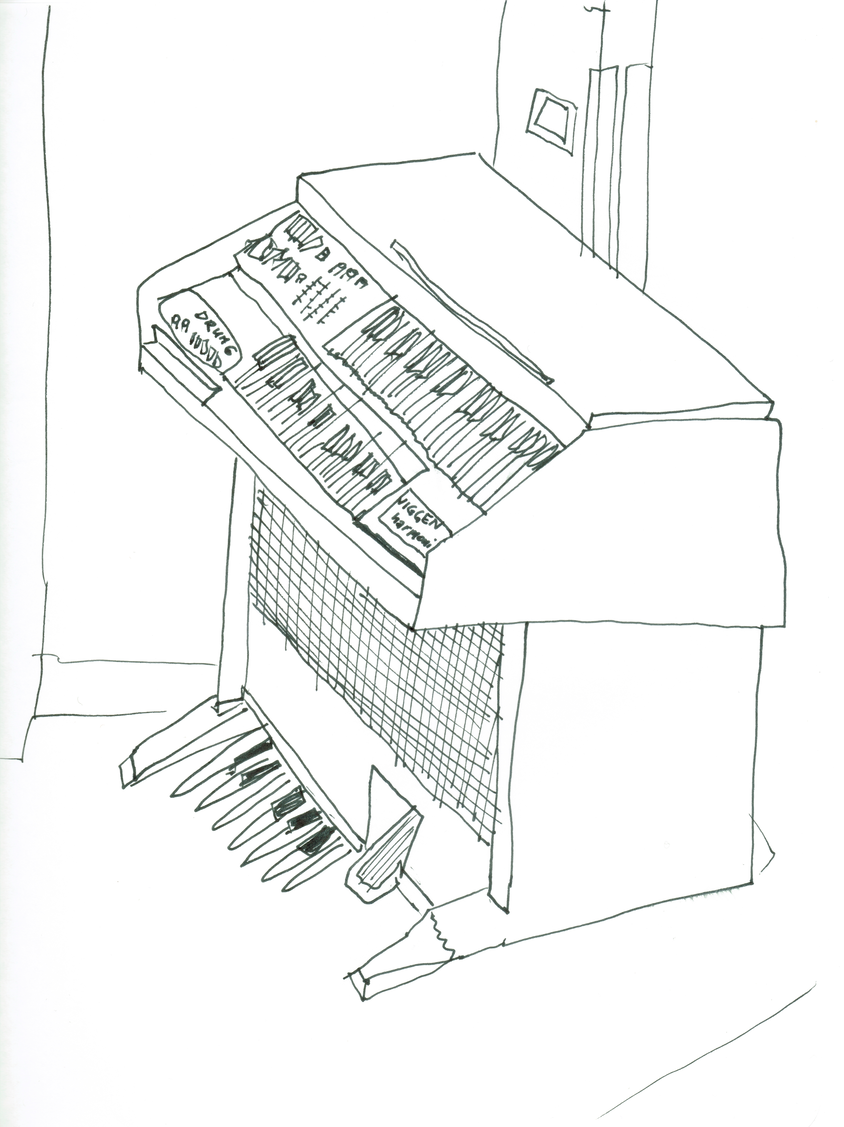

"Studio Lambert":

Fostex XR-3 four-track-studio,

ARP Omni synth,

Viggen Harmoni organ.

(Not pictured: KORG Volca Keys and MicroKorg)

MUSIC FOR THE MIND. THE CASE OF THE TRANSFORMATIONS

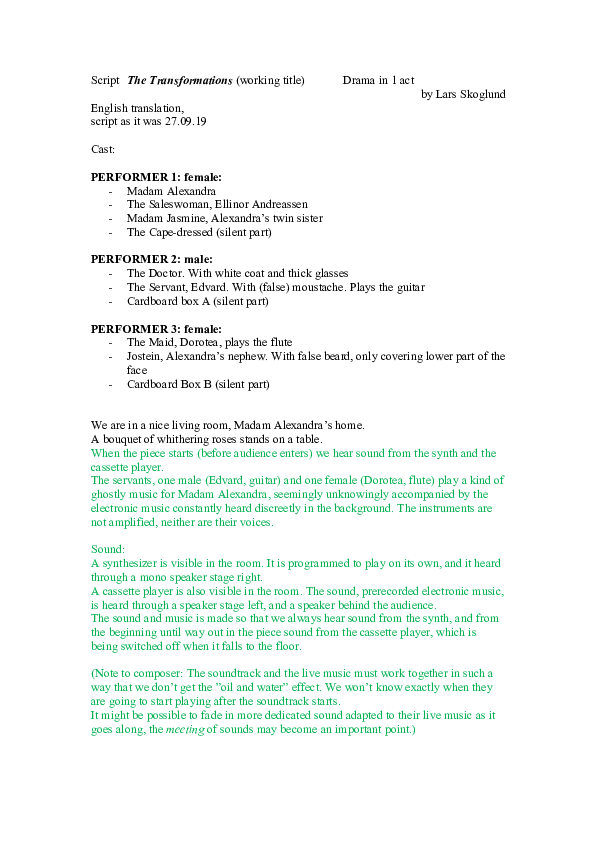

Probably the most strange – and perhaps even unplayable – piece I made during the Ph.d. period is called The Transformations. So far, it only exists as a manuscript for a play. It does, however, have several “notes to composer”, and many of those who have read it have told me how they experienced hearing their own theatre music in their imagination while reading the stage directions.

When reading the drama purely as text, the reader can imagine her or his own inner imagined music, such as in the following example, from the opening:

“Sound: A synthesizer is visible in the room. It is playing on its own, and is heard through a mono speaker stage right. A cassette player is also visible in the room. From it, we hear the sound of prerecorded electronic music through a speaker stage left, and a speaker located behind the audience.

Two servants, one male (Edvard) and one female (Dorotea) play a kind of ghostly music on guitar and flute for Madam Alexandra. Their performance, seemingly unbeknownst to them, is accompanied by the electronic music that is constantly heard discreetly in the background. The instruments are not amplified.”

In the manuscript, all music-related instructions are given in green color.

GIVING FORM TO A COLLECTION

As a composer I have worked a lot with a thematic that can be summed up in the question: What does it mean to give form to a collection?

Single sounds, detached instrument sounds, bits and pieces of recordings, sounds from nature, or from a city, or from the radio; and then this is all going to be combined and given a form where the sounds both build a whole, and still are identifiable as pieces of own realities.

I have wondered why I am attracted to working this way, and I believe that one reason is how the found material contains an energy that comes from its own life and connections. And this is something I very much want to exhibit and display.

SEARCHING FOR A FORM IN COLLECTED MATERIALS

As I was working on putting together the On Location piece, I came across the following statement by Joan Didion, which seemed to address exactly what I went through the process of trying to turn disparate lines into a narrative that can be read as a unified thread and understood by the reader:

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live.

(…) We look for the sermon in the suicide, for the social or moral lesson in the murder of five. We interpret what we see, select the most workable of the multiple choices. We live entirely, especially if we are writers, by the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images, by the “ideas” with which we have learned to freeze the shifting phantasmagoria which is our actual experience.

Or at least we do for a while.” [1]

[1] Didion, Joan: The White Album (1979), in We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live. The Collected Nonfiction. Everyman’s Library, Alfred A. Knoph, New York, London, Toronto 2006, p. 185.

JUXTAPOSITIONS. FAST FOOD FOR SLOW PEOPLE

Fast Food for Slow People is a piece that perhaps may seem like a curiosity next to the rest of the work presented in this exposition, since it does not have any audible text, but is purely instrumental. But there is still a text to it; before the premiere on a concert in Oslo in April 2019, I was asked for a program text, and decided at the last minute to hand in a strange little story I had written for my own amusement just before, and to observe how the audience would react to it in relation to the music.

This was of course a whimsical thing to do, but it also felt that I was motivated by how the piece itself is constructed, since it is all about juxtapositions.

It starts in an ensemble of four with pointillistic impulses which are overlayered with a short and slow microtonal flute melody. The ensemble then becomes layered with an electroacoustic soundtrack that sounds like robotic voices, with “solos” interweaving, made by sound from a no-input-mixer through a vocal filter, and the acoustic ensemble accompanying this with oscillating harmonies.

The second part of piece has a foreground with a pointillistic soundtrack with short metallic 1/3-tones, on top of very long ensemble multiphonics and slow harmonies, moving in pairs of flute and bass clarinet, violin and cello. I felt that the “juxtaposing” of an “outside” text was already embedded in the way the music was made. The music also often has a character of oration, with speech-like qualities in the purely instrumental music, over backgrounds that tend to “lie low”.

The program text is related to the Ideas for Stories that I present in the last part of this exposition as possible future plans. These are all texts I have some difficulty giving an account of, with their structures reminiscent of jokes without punchlines, or fables of talking animals, among other things. The abrupt cuts and omission of information point to the forms of the fragment and the miniature. There is perhaps something miniaturistic, too, in the relative lack of development in the music, with static rooms being entered, and kept going for a while. This also connects with the concept of the moment form that we can find, for example, in some of Stockhausen’s works and theorizing from the 1960’s.[1]

FORM AND TIME

Lambert, Lambert! is the final and most ambitious piece in the project. The piece is for three singers (not percussionists this time) and they alternately sing and speak. The music is all pre-recorded and, during the making of it, I had a scary experience that influenced its creation very strongly, technology-wise: My backpack with computer equipment got stolen, so I could not record digitally for a while. This made me focus exclusively on analog recording of the most basic kind: on a four-track cassette (with stereo mixdown in between on minidisc). Like the theatre composer in the story, I used two synthesizers and one drum machine. The limited resource, both in terms of how many sounds could be stacked on top of each other and in terms of what types of sounds, conceptually could use, became an advantage, rather than a problem. Accepting these limitations helped me greatly in shaping the piece.

For the production I was fortunate to collaborate with Tormod Lindgren, who both made the scenography and directed the piece. His background is in puppet theatre, and he had the very good idea to let the scenography recreate a miniature version of the world of the characters that was visible simultaneously with their full-scale realities. Since the storyline shifts in time between what is happening in the here-and-now and what is told in retrospect, this created, in a very direct and effective way, a simultaneity between memories of various near pasts and the present, in a kind of visual layering.

A table in the middle, with a small revolving stage, is the constant element that, in my opinion, gave the piece a togetherness that it needed, since it is quite dreamlike; the scenes and the monologues are sometimes border on sights or visions, but they do so while using very ordinary colloquial language.

I honestly have a hard time trying to make a résumé of the storyline in the piece, and even saying what its subject matter is. It involves some people, who are making a theatre piece about a historical figure called Lambert. One of the actors, Håkon is returning from a summer holiday trip. The lighting designer has trouble saying no to a friend who offers her apples. The theatre composer does not know how to score a central scene in the piece. Eventually we hear that somebody has broken into, and is living in, Håkon’s garage.

While I wrote the piece, I tried to plan the layout of the scenes would be, as I had done with ease in Sixty-Forty. But here, the only way to figure out what was going to come, was to write out the actual scenes. The light-mixer monologue in the opening was the start, and the whole work was written sequentially from there. It may look like a non-linear cut-up, but it was written linearly – exactly the way it is performed.

Unlike some music dramas, this piece does not have a lot of action, or dramatic content. Nobody dies or get hurt, and there is no clear message – as my director told me when we discussed it during the rehearsals. There are some elements slipped in from a grand historical drama, that some of the performers and stage workers are going to produce with their theatre group.

But fundamentally, the piece is more concerned with how life is filled with small events in the everyday. The story – or more accurately, the stories – are told in a way where their paths cross, similar to in a crime riddle, but without any violence having taken place. We gather that something is going on behind the scenes. There is probably some kind of love story between Håkon and the theatre composer, and Håkon has also left something or somebody behind. I planted little questions like this on purpose, to give the viewer something to wonder about and to sustain their interest.

Structurally, I am proud to have been able to create so much reflection in the piece following the short shouting scene where Håkon rehearses the “monologue” of his role figure Hallvard Magnus, yelling outdated abuse at Lambert, who does not appear. [1] [2] The nameless theatre composer has a hard time finding the music for this scene, and discusses her difficulties in detail.

As in Sixty-Forty and The Transformations, the performers play more than one role each (except the Håkon character, although he rehearses his part as Hallvard Magnus). In the script, the roles are assigned to the real names of the performers (like in Duke Ellington’s scores). The performer Ditte is the theatre composer and the (ex?-)girlfriend Ruth; the performer Natali is the lighting designer and Ruth’s friend Vera, who collects photographs. Their roles switch during the different time planes of the piece.

In this piece, the stories are really the fundamental element, more than the musical setting. Again, the music is more a kind of ambience and accompaniment. But I don’t cry any tears about this. I have to be very careful with how I use music to paint thought-pictures around what the characters are saying; this is really very important, because I need to make sure that their words stay open to interpretation! To choose to let the music be non-intrusive is absolutely a musical choice and decision. It is not a denial of the power of music; rather, it is an acknowledgement of the power of music!

A fun fact about how the sound of speech can be heard as music happened when I ran into a friend who had seen the piece, and referred to the opening spoken monologue about the light mixer as a song. In her memory (and she is an experienced theatre-goer) this was sung by the performer.

I wish the characters well. I am not interested in bringing out the worst in them. I am also not basing the piece on some conflict, I look for other “motors” to drive it forward, like planting questions for the viewer’s curiosity. And I had much pleasure disobeying the usual “show, don’t tell” dictum. This inversion of dramatic norms was like a guiding principle for me while developing the script.

[1] Connoisseurs of North-Norwegian humor may notice a similarity here to the story “Jo’an Peder” from the collection Vett og uvett (which would translate to something like Sense and Nonsense) by Einar K. Aas and Peter W. Zapffe, about the jealous Jo’an Peder, whose rival Direk visits their friend Løura. He stands waiting outside her house and finally calls out for Direk to come out. But then it turns out that Direk has left and went home more than one hour ago.

Aas, Einar K. og Peter Wessel Zapffe: Vett og uvett. Stubber fra Troms og Nordland. F. Bruns Bokhandels Forlag, Trondheim 1971 (first edition from 1942), p.68.

[2] Readers of Dag Solstad’s novel Shyness and Dignity will remember the long passage about how one Ibsen character “trembles slightly in his voice” in one tiny stage direction. Solstad, Dag: Genanse og verdighet (Shyness and Dignity). Roman. Forlaget Oktober, Oslo 1994, p. 7-37.

Fast Food for Slow People

Dedicated to Tøyen Fil og Klafferi

Program Text:

Suddenly the telephone rang. Nobody picked it up. Danielsen had a really bad headache now. Ulla had not written to him since that evening in Chicago. Goodness, how he missed her!

Thankfully he had the piano music. Piano music is the life, Ulla, he said laconically. He checked his e-mail.

One day the doorbell rang. A little pussycat was standing there. The cat looked incredibly sweet, but it had a language so terrible that it made him blush and cover his ears. Or he found other ways to drown out the sounds, like turning on the vacuum cleaner, although the place was as clean as possible, or he checked if the drill had battery power left. But the pussycat of course understood what he was up to, so it just waited with saying what it had to say until he stopped making noise.

A guy with a yellow cap walked by, and swung his arms wildly while leaning back at the same time. He had pulled the cap pretty low into his eyes, and it looked pretty comical. Then he stopped and had a smoke. Good that I don’t smoke, not so often at least, he thought to himself.

The sound of a trumpet filled the place. Applause was heard. This must be a recording from a concert, he thought. He recognized the music. It was The Musical Sugar Top.

Wish I was in Sweden now, he thought. Or not in Sweden, but on the way to Sweden.

Norwegian original:

Plutselig ringte telefonen. Ingen tok den. Danielsen hadde skikkelig vondt i hodet nå. Ulla hadde ikke skrevet til ham siden den kvelden i Chicago. Nei og nei, det var et savn. Heldigvis hadde han pianomusikken. Pianomusikk er livet, Ulla, sa han lakonisk. Han sjekket mailen.

En dag ringte det på. Det stod en liten pusekatt der. Katten så utrolig søt ut, men den hadde et språk som var så fryktelig at han rødmet og måtte holde for ørene. Eller han fant på andre ting for å overdøve det, som å skru på støvsugeren, enda kåken var så shina som overhodet mulig, eller han testet om det var strøm på den batteridrevne drillen. Men pusekatten gjennomskuet selvfølgelig opplegget hans, så den ventet bare med å si det den skulle si til han hadde sluttet å bråke.

En fyr med gul topplue gikk forbi, og svingte voldsomt med armene samtidig som han lente seg bakover. Han hadde trukket lua temmelig langt ned i øynene, og det så temmelig komisk ut. Så stoppet han og tente seg en røyk. Jammen godt at jeg ikke røyker, ikke så ofte i hvert fall, tenkte han. Lyden av en trompet fylte lokalet. Så hørtes applaus. Dette må være opptak fra en konsert, tenkte han. Han kjente igjen musikken. Det var Den musikalske sukkertopp.

Den som hadde vært i Sverige nå, tenkte han. Eller ikke i Sverige, men på vei til Sverige.

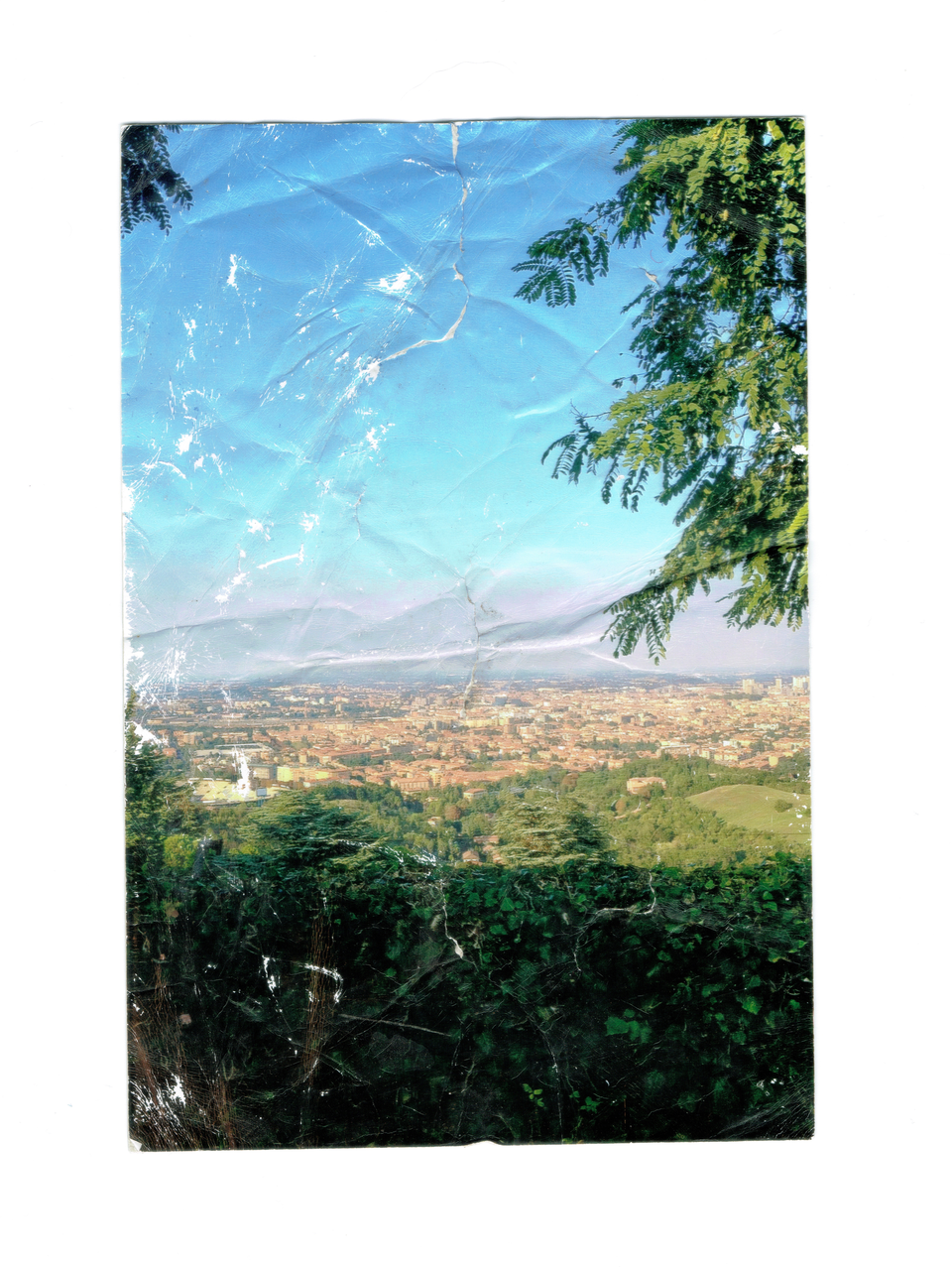

THE FOUND PHOTOS ON STAGE

In the piece Lambert, Lambert! there is a long sequence (from 20:06 to 25:46 in the video documentation) where the libretto is based on verbal descriptions of found photos from my collection. About midway through, the performer Natali Abrahamsen Garner gets up and starts throwing the actual physical pictures up in the air, so that they fall down like snow. As mentioned, I have had qualms about using the pictures in public, but I thought that this was a responsible way of including them, since they would be seen from a distance, and not displayed in individual detail (like pictures in a gallery, for instance).