Introduction

Music education in the Dutch elementary schools is set in motion. In the last years more and more tendencies appear to structurally increase the amount of music lessons and improve the quality. This has culminated in the document ‘Handreiking Muziekonderwijs 2020’ which was commissioned in 2014 by the Minister of Culture and Education, Ms. Jet Bussemaker:

“The attention to music and music education given to children aged 2,5 to 12 years has grown in recent years, after decades of creeping decay. Those responsible have joined hands in many places, sharing a vision on the importance [of music education]. Parents and grandparents, specialist and generalist teachers, school and city officials, politicians, musicians and media professionals, many have come to the same conclusion: music education in the Netherlands needs a boost.

The urgency is there: if we together make the choice to work coherent and structured, we can quickly make progress and take advantage of the existing expertise and the cultural and educational infrastructure which is still there. If we do not do this together, the risk grows that the size and quality of music education is slipping [further] into a deplorable level and good music education will only be reserved for a privileged few.”

The mentioned decades of creeping decay have led to what could be called culturally neglected generations. And this has led in its turn to a now missing audience that was not educated to value music as an art form, to perceive music in a concert hall[1]. Of course a change as mentioned above is only possible with quality teachers who were educated on a high level and who are specialized in teaching children aged 4 to 12. For that reason, in my opinion, there should be a separate education for elementary school music teachers, next to the already existing Docent Muziek as offered by most Dutch conservatoires. An educated elementary school music teacher should be able to generate a curriculum for musical learning, designed for the eight grades of Dutch elementary schools, from group 1 (age 4) until group 8 (age 12), taking into account the specific situation at his of her particular school and – of course – the children in the classroom. In my opinion this is a demanding task that needs at least four years of professional education.

Here is another quote from the ‘Handreiking Muziekonderwijs 2020’:

“In the Netherlands, with all its fragmented responsibilities and mandates and sometimes only partially overlapping ambitions it is difficult to achieve a better quality of music education. In the countries around us and also for example in Scandinavia, Germany, Brazil and Venezuela we see how relatively quickly, simply and coherent proven methods are used and the number of children having high level music lessons is considerably increasing annually. This is also possible in the Netherlands.”

One of the coherent proven methods can be found in Hungary, and since decades also in many other countries all over the world, like the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, Taiwan, etc.: the Kodály method. Even though many people have a problem with the word ‘Kodály method’ because it is not a paved and unified method but rather an approach, a philosophy which knows assimilations to different countries, cultures and situations. In this document I will refer to Kodály as the Kodály-method if I actually mean the methodology of Kodály teaching. With the Kodály-philosophy in mind a concrete curriculum can be worked out adapted to the situation in which it is used. The core of the philosophy is singing:

“What is the most important prerequisite for achieving success in the study of music? - I can answer that question with a single word: singing. But I can say it over and over again three times if you like: singing, singing, singing again.”

This quote by Zoltán Kodály has a direct connection to what is said in the ‘Handreiking Muziekonderwijs 2020’:

“Now that there are so many people in the Netherlands who want to give music a bigger place in our daily lives, there is a momentum and we may – with united strength and power –

structurally improve music education in the Netherlands. The aim is to make every child - preferably through an unforgettable 'key experience' – enthusiastic for singing, music making and listening to music.”

So the good will is there to structurally improve music education in the Netherlands, based on singing. Of course enthusiasm is an important thing in musical learning, as in learning in general. But we can not plan a ‘key experience’ of an individual, we can only provide possible key experiences by striving for musical quality in the classroom – by letting the children become musicians themselves, using the instrument which they take with them all the time, which is personal and common at the same time, and through which all the people express and always have expressed themselves, their feelings and their (musical) culture: the singing voice. Having access to the own singing voice means having access to cultural heritage and culture in general[2].

Above I spoke about music education for children aged 4 to 12. But of course this is not the period where music education starts and ends. Being asked when music education should begin, Kodály answered: “Nine months before the birth of the child”. Later he refined his answer: “I would go further: the musical education of the child should start nine months before the birth of the mother”. Preschool music education and programmes like ‘Muziek op schoot’, where children and parents are learning in music together, seems actually an outcome of a comparable view.

It is very interesting that the Kodály-approach is explicitly mentioned in the “Handreiking Muziekonderwijs 2020”:

“The learning strands have to be tested by the quality and the impact of musical learning – pedagogical visions, such as the Music Learning Theory for stepwise progression in musicality, ‘Guildhall-skills’ in improvisation, the Kodály approach for developing the listening skills and singing (together), Da Capo for the combination of general musical skills and instrumental playing skills.”

The elements mentioned here, stepwise progression, improvisation, listening skills and singing (together) and the combination of general musical skills with instrumental playing skills, are in my view all part of the Kodály approach already. And even more skills should be mentioned: physical movement to experience musical structures, as taught in the Dalcroze-method[3], has entered the Kodály approach as well as composition, polyphony and awareness of musical form. So the Kodály approach is a very broad and thorough approach of musical learning.

At the same time there is a danger in the attempt to adapt the Hungarian Kodály-methodology to other (musical) contexts. For example, to what extent is it possible to ‘transport’ methodological elements of music teaching to a classroom elsewhere, without loosing the connection to the original curriculum? What will remain from the ‘original’ Hungarian Kodály methodology, and to what extent can we then still call it Kodály teaching?

I believe that only fundamental understanding of the Hungarian Kodály methodology can prevent us from calling our teaching ‘Kodály’, while it may have become something completely different. From that understanding we can ‘refind’ a comparable methodology here, in our musical context.

In 2011 the well-known psychologist Howard Gardner conducted a research by interviewing eight music teachers who call themselves ‘Kodály-teachers’. His research question is about the role of Kodály-teaching in music education: “Signature pedagogy or surrogate profession?” Two of the interviewed teachers, Sidney and Halle, express exactly what I mentioned above:

“The Kodály philosophy led to the development of a signature pedagogy that incorporates various disparate music-teaching elements into a single method of teaching music. The elements themselves are not unique to Kodály, but their use within a clearly defined method is. Interestingly, while each of the interviewed educators strongly identifies themselves as “Kodály” not one of them strictly adheres to the tenants of the methodology. Sidney, who incorporates contemporary music elements such as hip-hop in his Kodály program, states that the mother tongue of traditional Kodály (Hungarian) is not the mother tongue of his students. In contrast, Halle, whose formative teaching background was in Eastern Europe, worries that Kodály in America is “not the real Kodály.””

The danger is that some teachers so urgently would like to teach music ‘as in Hungary’ that they might think that it is easy to teach that way in another musical context by just copying single elements from single music lessons they might have observed there. But it is not a bag of tricks. The most important thing that has to be understood in my view is the depth of the connection between Hungarian folk song repertoire and the methodology as worked out in Hungary. Kodály wanted to save valuable Hungarian folk songs from being forgotten and from disappearing from the Hungarian culture. Here in the Netherlands this process has already happened: many songs are already forgotten and have disappeared from the Dutch culture.

Intermezzo

Some of those forgotten songs can be found in "Het Antwerps Liedboek", a collection of song texts without music notation. Apparently the melodies were known well enough so it was not necessary to print them. Among others, this collection belongs to the most beautiful song repertoire of the musical heritage of the Low Countries of the 16th century. At least some of these melodies and texts should be part of the song repertoire that is passed on to future generations. Of course not for reason of patriotism but for musical and esthetic reasons. The texts are often related to historic events, so also for understanding the past it could be worth singing this repertoire.

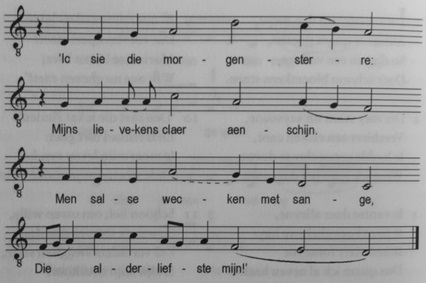

A beautiful example is the dorian song 'Ic sie die morgensterre', a love song that was first printed in 1539:

This melody was popular in the Low Countries and in Germany already in the 15th century. Many contrafacts were made throughout the 16th century and printed in different editions up to the beginning of the 20th century. But for the young generation of these days this song is lost.

Interestingly, still modal melodies appear in popular music. The song "Mad World" became a world hit in 2003, actually being a cover version of the song by Tears For Fears in 1983. Apparently people love dorian melodies, so why not teaching an old Dutch dorian melody to children in elementary school?

In the Netherlands we can speak of a pluralism of musical backgrounds when we teach a class of children. In some Dutch families singing songs belongs to daily life, but the song repertoire may be different. In other families the parents do not sing at all, and also active music listening is not a part of family life. Some children might have private music lessons in a music school, but that is not a guarantee that singing is involved. And - especially in the bigger cities - there is also a pluralism of cultural and religious backgrounds. So if we start teaching children in group 1 and 2 at the age of 4,5 to 6 (the so-called ‘Kleuters’), which song repertoire is at hand to build a methodology or a curriculum? In my view the first thing to do would be teaching music to the children: songs, singing games and folk dances, where they are the performers themselves. Of course songs that are appropriate for their age and the abilities of their singing voice. This we could call the front-end of music education. On the back-end it is us – the teachers: we have to know exactly about the musical content of that song material, concerning melodic structure, harmony, form, meter, rhythm elements, toneset, ambitus, tonality, etc. We have to choose wisely a repertoire for the children that provides further musical learning, such as aural skills, reading and writing skills, singing skills and repertoire experience. So this is about taking children and children songs seriously, also if the melodies are very very simple in the eyes of a grown-up. And this is also about quality, not only in terms of musical performance, but concerning the repertoire as well. Though there are many well-composed ‘pedagogical’ children songs, we have to be critical about the melodic, harmonic and textual quality. This is a different subject because the definition of quality is affected by (personal) taste, culture and tradition. There are songs which children love and which musicians would consider of less quality. So there must be a certain freedom of repertoire choice. And – not to forget – it is also important to incorporate songs the children come up with[4].

It is the teacher’s profession to bring all of this together to build up a song and game repertoire for group 1 and 2 which covers the development of a covering a variety of musical skills: use of the singing voice, singing in tune, development the rhythmic sense, feeling a regular beat, performing rhythm and melody, feeling the relationship between regular beat and rhythm, tempo, distinguishing high and low tones, distinguishing loud and soft, awareness of tone colour (timbre), development of inner hearing, active music listening[5].

As mentioned above, the analysis of song repertoire is the fundament of a responsible choice for reaching musical goals. Looking at the song collections frequently used in Elementary schools in the Netherlands it is intriguing that none of them has ordered the featured songs by musical content. The most famous one, ‘Eigen-wijs’, orders the songs according to the eight groups of Dutch elementary schools: songs for group 1&2, 3&4, 5&6 and 7&8. Then some topics are chosen to subdivide each set of songs, such as singing game, instruments, autumn, Sinterklaas, Christmas, Winter, Spring, animals, Summer, from countries far away or ‘shivering’. There are also some uncategorized songs in the collection. At the end of the book there is an alphabetical index. So if a teacher is searching for a song in the minor key or for a three-note song or for a song with a small range or for a song with a certain rhythm pattern there is no indication given. Of course a song collection is not a method. And of course Eigen-wijs is a good source for repertoire. But the teacher has to know exactly why a certain song is chosen because music lessons are not separate lessons where you just sing a bunch of random songs. It is an education in music, so the lessons are connected to each other. And with every song and game the children learn musical elements providing long-term learning. Every song and game contains a deeper musical layer as a preparation for next steps in developing particular musical skills. So there is a (practical) need for a song and game collection which is ordered by musical content and educational goals.

[2] This does not mean that instrumental teaching is completely abandoned from music education. But singing is a prerequisite in its own term for instrumental education.

[4] So no musical style is actually excluded. In the biografies of most children schools are the only place where they have the chance to step out of their socialization to learn things that are not offered at home. And schools have also a responsibility to pass through cultural and musical heritage to future generations. Also musical styles belonging to popular music are not excluded and could be part of the curriculum. But the most important reason should be a musical one: because it serves musical learning goals and because it is a song of good musical quality. It is not only one particular musical style on which we should build a whole curriculum, because the world of music is so much broader than what for example pop music has to offer. To put it in a rather polemic way: we do not teach children to read and write language with the goal to finally only read comic strips. We also want them to be able to also access literature and poetry.