Carlo Maria Michelangelo Nicola Broschi [1] (Andria, January 24, 1705-Bologna, September 16, 1782) was one of the most famous castrati singers of the 18th century. Carlo Broschi chose the pseudonym Farinelli in gratitude to the Farina brothers, patrons who paid for his studies and maintenance for many years.

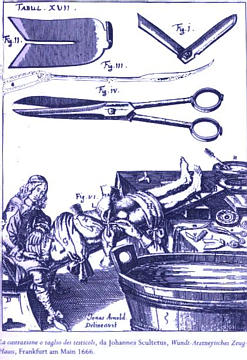

Castration[2], according to Herodotus, was a practice that dates back to 5,000 years before Christ, but without any artistic purpose, but rather torture.

“A register is a series of homogeneous sounds produced by one mechanism, differing essentially from another series of equally homogeneous sounds produced by another mechanism.” Manuel Garcia Junior

The mechanism of the castrati was totally different from the rest of the mechanisms. Being castrated before their development, they did not receive the hormonal supply of testosterone, stopping the growth of the larynx but at the same time not being able to limit the growth of other structures. They preserved a child’s voice, in a man’s body. His voice had a lot of power. In addition, they possessed large lung capacity and muscular strength. They tended to be tall and to develop a lot the ribs. This helped them to perform their vocal technique exercises better and also to have more breath control. The Castrati had the physical strength of man, their larynx and vocal cords were short and flexible, allowing them to sing with great agility. They were tall with pale, smooth skin, prone to obesity, narrow shoulders, rounded hips, lacked beards and body hair, although it was abundant on the head. However, the resonance chambers such as the rib cage and lung capacity were very large.

His family was part of the lower nobility. It is rumoured that he was castrated as a result of a fall from a horse. Farinelli [^4] was sent to a conservatory. There he received extensive vocal training, composition and improvisation lessons. For the latter, Farinelli became famous, since he enriched the works with his agile and virtuosic improvisations. Under the instruction of Nicola Porpora, he acquired a voice of marvelous beauty. His first public performance was in 1720, with the Angelica e Medoro, from Porpora. From then, he started singing female roles regularly in operas. Johann Joachin Quantz wrote: Farinelli had a penetrating, full, rich, luminous and well-modulated soprano voice, ranging at the time from A below middle C to D three octaves above middle C… Her intonation was pure, her vibration wonderful, his breath control extraordinary and his throat very agile, for which he sang the widest intervals quickly and with the greatest ease and security. The passages of the work and all kinds of melismas did not represent difficulties for him. In the invention of free ornamentation in the adagio it was very fertile. Farinelli left for Spain in 1737, where he lived for almost 25 years. His voice was used to cure King Philip V, the first Bourbon, of his melancholic depression. This had not only end up giving him power, but also the official name of prime minister. For two decades, night after night, he was asked to sing the same arias to the king. He was given the rank of knight in 1750 and was decorated with the Cruz de Calatrava. He used his power at court to persuade Ferdinand VI to establish Italian opera. He also directed the Royal College of Santa Bárbara for Children Musicians, popularly known as “Casa de los Capones”. After the accession of Carlos III, Farinelli retired in 1760 to Bologna until his death.

He was somewhere between a soprano and mezzo-soprano and stood out for his ability to improvise and make ornaments. Carlo Broschi could produce more than two hundred and fifty notes in a single breath and holding it for more than a minute. He increased or decreased the volume at will and could perform vocalizations for fourteen bars with a single intake of breath. His ability was such that some thought that in singing he hid some instrument that allowed him that quality of voice while inhaling new air. Farinelli jumped from one note to another with a precise tuning. His voice vibrated freely like that of a goldfinch and he sang the fast notes (coloratura) like nobody else.

He performed male and female opera roles. Some of the songs and operas that he performed are:

Rosell Antón, J. A. (2021). La voz del castrato Farinelli. ↩︎

Romero, S. (2016, September 15). Te contamos La Espeluznante Historia de los castrati. MuyHistoria.es. Retrieved June 27, 2022, from https://www.muyhistoria.es/h-moderna/articulo/quienes-eran-los-castrati-751434546477#:~:text=Los%20castrati%2C%20%E2%80%9Ccastrato%E2%80%9D%20en,la%20hora%20de%20entonar%20melod%C3%ADas. ↩︎

McSpadden, R. C. (1953). The castrati: Their art and Influence. ↩︎