Artist-researchers Pietarinen and Qureshi aim to utilize reindeer blood as a reindeer herding by-product rather than treating it as a waste product. It also examines the concept of a living design medium, in which simple living organisms (reindeer blood) can be utilized for material production, material-driven design and co-design.

Can design optimally allow chaos to form potential symbiotic relationships with natural waste? Can multidisciplinary working groups, like biochemists and artists-researchers, create a new life by equipping nature with the diversity of natural waste? There are a variety of ways to deal with waste materials. Using biochemistry techniques and biomaterials creatively can help create innovative products. All of these are highly significant questions, but it is nearly impossible to address them in this pioneering article. However, to initiate a response to these questions, this study uses reindeer herding by-products to design new patterns and to feed microbial life. Therefore, a circular process and value chain are created to maximize the reuse and recycling of industrial by-products.

Bioart plays an important role in critically challenging emerging life science applications, stimulating scientific thinking, artistic practices, and methods to create artworks to contribute to new research questions and pioneering technologies. A BioARTech Laboratory (established 2021) at the Faculty of Art and Design of the University of Lapland in Finland focuses on developing new knowledge about bio art. This laboratory seeks to develop activities that combine bioart, material study, textile art, creative research, biotechnology and science. It can be used to develop innovative design and art practice to work with nature (biology) and the non-human, such as live tissues (i.e. materials engineered by nature itself), microbes or living organisms (birds, insects, trees and blood), to bring about new design solutions and life processes. (Pietarinen et al., 2022a; Pietarinen, 2021, p. 275-284).

Vitality and Chaos with Our Trash

Reindeer are one of the main attractions for tourists visiting Lapland. Northern Finland boasts a wide variety of small businesses that make and sell products made of reindeer, with hides, antlers and bone used for souvenirs, interior textiles and clothing as well as for utility and decorative objects. Most of the tourism and design businesses in Lapland use reindeer-based materials either directly or indirectly. (Pietarinen et al., 2022b) There are aspects of culture such as reindeer herding, tourism enterprises and the use of reindeer materials in crafts that are central to Sámi cultures. In Finland, the Sámi Duodji Association nurtures the knowledge of crafting traditional Sámi handicrafts. At the Sámi Education Institute in Inari, it is possible to study Sámi handicrafts, where reindeer materials play a strong role (The Sámi Education Institute, 2023). There are also other aspects of Finnish culture that include reindeer herding and tourism. For example, products featuring reindeer are creations inspired by the Finnish world of experience: reindeer hides commonly decorate Finnish homes much like traditional rya wall rugs; souvenirs are crafted from horn and bone; shops sell a range of reindeer meat products; and live reindeer are a premier attraction provided for tourists by the experience industry. (Pietarinen et al., 2022b)

The Future Materials and Design (2022) workshop was organized by the Future Bio Arctic Design project (F.BAD II 1.7.2021-30.9.2023), held at the Faculty of Art and Design at the University of Lapland in Finland. The target group was Lapland’s textile and clothing design entrepreneurs. A total of six Lapland companies and entrepreneurs participated in a two-day workshop. The context of the workshop focused on the Lotus Blossom design method which involved free product ideation and rapid smart textile product prototyping. Moreover, it consisted of organising concepts around an overarching theme of arctic plants and green chemistry, before breaking them down into more specific sub-concepts. During the workshop, different and alternative developments as well as factors of change and surprises were observed. This led to innovative idea discussions which were not even previously taken into account. These kinds of working methods generated new scientific ideas, design thinking, artistic practices and product design. This unfinished F.BAD II process of understanding is part of the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) Future Bio Arctic Design II project in Finland (Natural Resources Institute Finland, University of Lapland, and Lapland University of Applied Sciences, 2021–23; Higgins, 1994, p. 144-145).

As a part of the workshop’s creative idling (Csikszentmihalyi et al., 2014; Pietarinen, 2019, p. 118-120; Raffaelli et al., 2023), a Blood Bar armband turned out to be a sort of wildcard of design thinking and innovation process. The main idea of the armband is that it includes a pillow, which is filled with reindeer herding biomaterial and blood; thus, it acts as a mosquito bait and a repellent at the same time. It is known that reindeer can lose up to half a litre of blood per day due to mosquitoes. Multisensory material experiences are a possible way of experiencing materials in people’s verbalisations; thus, workshop participants were not only asked to describe reindeer materials, but also to share their experiences and tell stories about reindeer. It was a matter of the diversity of trash and biophilic design—the humans’ positive responsiveness to nature, which enables the direct experience of natural elements and reminded the artist-researchers of a shared authorship. By letting the material guide us through the process and by viewing materials as something living, we allow the materials to have authorship and play an active role in the creative process (Pietarinen et al., 2022b, p. 212-227; Kanwal & Awan, 2021; Parsaee et al., 2019).

This part of the creative idling created the central research questions for Pietarinen and Qureshi: How does aterial research, a living design medium, offer a new perspective on (bio)materiality, like the relationship with animal by-products? Currently, there are roughly 200,000 more reindeer living in Finnish Lapland, a region of about (122 936 km2) in Finland, than there are people, about 18,000 (James, 2022). According to an estimation by the Reindeer Herdings´ Association (Paliskuntain yhdistys), almost 60,000 reindeer were slaughtered in Finland during the winter of 2021. About one-third of reindeer blood is used either as a raw material for feed and fertilizers or as food. Reindeer blood is used as food for dogs because it contains high-quality protein with good digestibility and is rich in iron, sodium and vitamins. Dogs tolerate the blood to a limited extent, and it is an easily perishable raw materials; therefore, the production process is a challenge that would require considerable investment (Reindeer Herders’ Associations, n.d.). Despite this, annually more than two million kilos of waste accumulates from reindeer slaughterhouses. Reindeer blood is also becoming waste because blood collection has not been organized profitably partly because of the stricter hygiene regulations. (Muje, 2019, p. 23-25; Mattila, 2019, p. 26-29; Guttorm, 2022).

Dutch designer Jalila Essaidi argued, that the push for more sustainable design solutions is misguided. She suggested that design should optimally allow chaos to form potential symbiotic relationships with our trash. She instructed designers to equip nature with the diversity of trash to work its magic faster. (Essaidi, 2021). This reminds us that the earth is a closed system and a direct contrast to the reality of man-made environments. Would political responses to public problems change if we were to seriously consider the vitality of materiality, pursuing this task by depicting reindeer blood as an actant rather than as a passive means under (non)material waste? Is it even possible to change patterns of consumption and face reindeer herding by-material (blood), not as waste? The downside is that the knowledge of intrinsically inanimate matter may be one of the impediments to the emergence of more materially sustainable modes of material research, design and consumption (Bennet, 2010, p. 9-10; Benyus 2002, p. 251-258).

Bioart describes the dialogue between art and science, which essentially involves organic matter as material and biotechnological methods as a tool of artistic expression. A living design medium incorporates simple living organisms, material-driven design and co-designing, with something having its own agency (Camere & Karana 2018, p. 570-584; Karana et al. 2015, p. 35-54). Given this motivation, Pietarinen and Qureshi, scientifically used arctic raw material (reindeer blood), as an information-rich material with specific properties to create a deeper understanding of bioart. The diversity of natural waste can be utilised by multidisciplinary working groups, such as biochemists and artists-researchers, to give nature a new tenancy to life. Through the use of animal by-products, a circular process and value chain can be created to enhance the use of industrial by-products with significant reuse and recycling potential.The philosophy behind the smartness of arctic raw materials is about seeing the unseen. The potential in the resources that we have on our doorsteps can guide our exploration of how to use, perceive, and comprehend them in more innovative, sustainable and comprehensive ways. Such as, to see things that are outside of human perception, like observing the birth of a snowflake through a microscope (Dumitriu, 2023).

Co-designing with Blood (Living Design Medium)

The main focus in Life Between Art and Blood research is on material-based design and experiments, not on product design yet. Multisensory material experiences, rapid experimentation and outlandish ideas were ways of experiencing materials in Pietarinen’s and Qureshi’s visualisations. They employed reindeer blood that had been frozen, heated, air-dried, and diluted (with water or natural oils) not only as a substance or medium but also as a topic for shared experiences using senses like smell and touch. This brought a three-dimensional, multisensory and tactile aspect to the reading of materials and familiarised artist-researchers with blood through sensory modalities such as smell and touch. (Pietarinen et al., 2022b; Karana, 2010, p. 193; Sonneveld & Schifferstein, 2008, p. 41-67).

Experiments were documented for further research that used photos as well as laboratory diaries, process notes and material-based design kept by the artist-researchers. The integration between blood structure, texture, material and form were central tools, techniques and methods for artist-researchers striving towards ABR and interdisciplinary and sustainable processes. The material-based design process formed several research questions: How could reindeer blood generate new scientific thinking, design processes and artistic practices? How could blood be applied, bound or painted as an earth oxide on different materials? Pietarinen and Qureshi present their analysis using a theoretical framework informed by bioart (Berger et al., 2020; Jain, 2014) as well as by a multidisciplinary experience of the processes (Wastl-Walter, 2016). Both bioart and textile art and design areas play an important role in critically challenging emerging life science applications, stimulating ABR and artistic practices to constantly propose new questions instead of solutions. In this sense, the results of the research are speculative design and place themselves in the field of critical design (Speculative and Critical Design, SCD) (Kääriäinen, 2021, p. 133-143; Koskinen et al., 2012).

In Vibrant Matter, the political theorist Jane Bennett shifted her focus from the human experience of things to things themselves. She examines the implications of vital materialism through discussions of commonplace things and physical phenomena, including trash. (Bennet, 2010). It seems increasingly logical to treat nature as a living entity, similar to how we see humans as individuals. The aim is ambitious because we should recognize higher intrinsic value not only to humans, but in non-human nature as well (Rauhala, 2021; Ballardini & Casi, 2020; Rauhala, 2017). Science-based information, as well as the visualisation of its artistic imagination, can be found in the nexus of art and the biological sciences. It lies in the complexity of organic life, biotechnological methods (microscopy) and living organisms/animal by-products (reindeer blood) that inspires artists to recreate it in the form of a visualisation or for the scientists to understand in scientific contexts.

Blood and rust are some of the most difficult substances to remove once they have stained a fabric. Blood is made up of liquids and solids, while rust is iron oxide and is harmful to fibres. Various means are used to get rid of both substances, such as hydrogen peroxide, rubbing bar soap, dish detergent, white vinegar, toothpaste, baking soda, salt, Coke, lemon juice and cold water. The artist-researchers goal was to attach blood firmly to the base material, like on wood, paper, glass, man-made and natural fibres and fabrics, not to remove it. Blood transferred unpredictable colours and patterns to the fabric, biting firmly into the fibre. The earthy shades of red-brown, orange and ochre were like properties borrowed from nature—an exploration of biomimicry, which means mimicking good ideas from nature and transport them into design or innovation. The strength of the colours lies in nature’s ability to combine simple materials with clever design using minimal sources. (Benyus, 2002; Kanwal & Awan, 2021; Kapsali, 2016, p. 14-15). See Figure 1.

Figure 2 illustrates that the artist-researcher (Qureshi) initially intended to use reindeer blood as the painting art material. This may reflect negative emotions and images in people’s minds outside the research context. For a layperson, the relationship with the material cannot be logical, as colour works as a metaphor. If we think about the history of the colour red and its relationship with blood, it is at the same time a source of life, passion and death. It is identified with states of alert, danger, prohibition and urgency. It is historically unstable, precious and known as a colour of marriage, mourning, grace and the underworld. The Sámi shaman drums were also painted red colour, which bears associations with life and blood. The colour red is said to be pronounced as Sámi worshipping a stone sieidi (storjunkare), which was smeared with the blood of a sacrificial reindeer. South African San Bushmen made rock paintings with a paint partly composed of eland blood. Only a few attempts have been made to study the pigment used in paintings in Finnish rock paintings. More analyses would be needed to determine if other components, such as blood, were mixed in the paint to serve as binders or for some symbolic reason. (Lahelma, 2008, p. 59-61, p. 130-131; Luho, 1971; Stahl, 1986, p. 144-45). Though it is not new in the field of art using blood or translating the artist's blood into data. Since at least the 1970s, modern and contemporary art and artists have used blood. For example, Katy Connor’s Untitled-Force (2011), Jeroen Van Loon’s Cellout.me (2015) and Tom Corby’s Blood and Bones (2013-16), open up discussions about gender identity, disease, racism and violence. In British-Indian sculptor Anish Kapoor’s work, a blood-red colour tinges and scores a wound on the surface and transforms stone, metal and canvas into blood, flesh and sensitivity—a secular relic of suffering humanity. (Connor, 2023; Corby, 2014; van Loon, 2023; Kapoor, 2022; Røstvik & MacDonald, 2019; Patoreau, 2016).

Creative idling opened a window into the blood as a material, colour and texture. To explore further, Pietarinen and Qureshi painted handprints in blood on (leather) paper to continue their investigation. Salt was then added on top to observe potential reactions. To study the changes in colour and the absorption of the blood into the wood, the artist-researchers painted the thin wood strips with diluted and non-diluted blood and left them for weeks. To go even further, they submerged several textile swatches in blood, either diluted or not. Figure 3 shows each of these instances. The goal was to first determine what the visualisation was rather than attempt to quantify chemically how each of these materials reacted to each other. The most interesting aspect of creative idling was not the patterns but their tactile and multisensory qualities. As a Finnish designer, Tapio Wirkkala states in a video documentary (2016) that the eye does not sense shape as sensitively as the sense of touch while the fingers can tell the truth (Yleisradio Oy, 2016).

Visual Traces of Cartographies

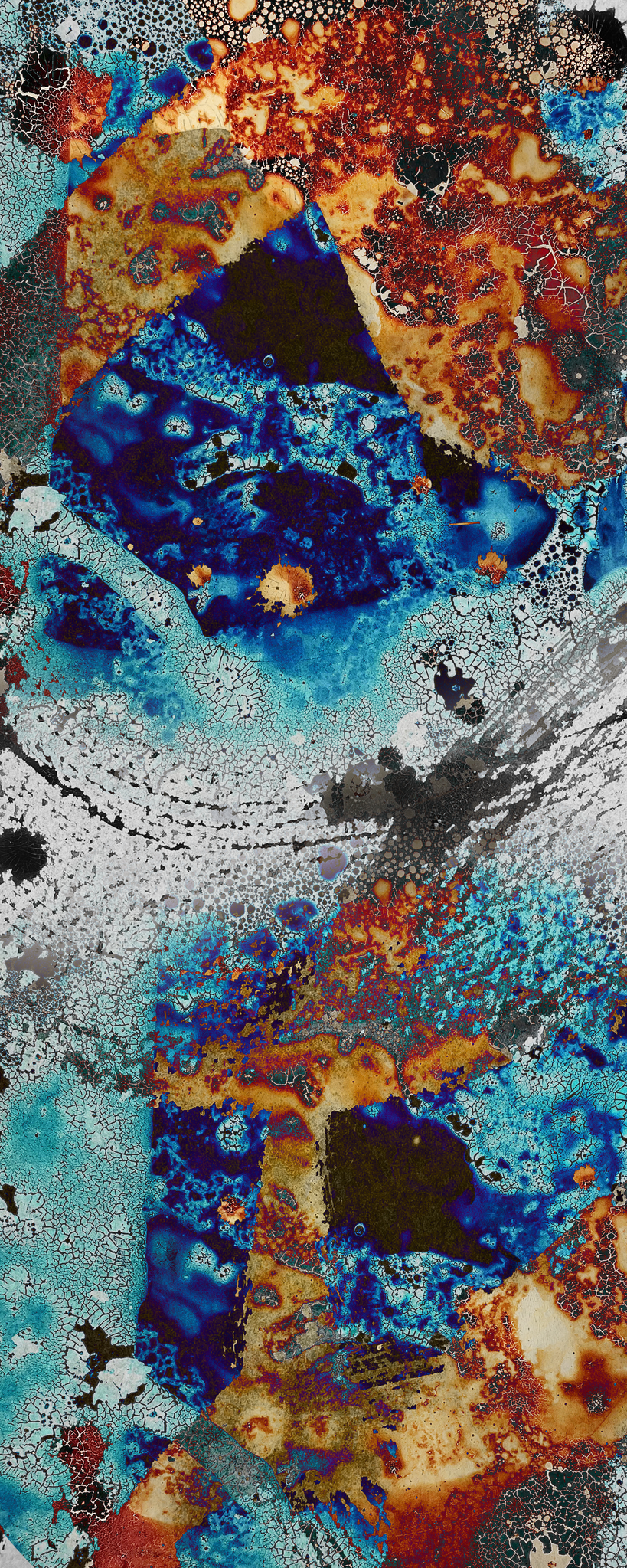

In this study, by bringing this readily available but discarded organic arctic raw-material (reindeer blood) under the scientific lens, the visual aspect became quite evident. As seen in Figure 4, upon enlargement and experimentation with the digital tools, reindeer blood provided beautiful imagery and traces of cartographies, which were then incorporated into textiles for exhibitions worldwide. The video produced using the same photos is shown in Video 1. Co-authoring identities and bioart textile installations in the National Gallery Prague, Czech Republic (2022), Entanglements South-North in Goethe-Institute, Namibia (2022) and Connectivity and Creativity in Times of Conflict conference (Method Art Track) held by the Faculty of Design Sciences of the University of Antwerp in Belgium (2023) are just starting points for a layered dialogue for identifying some logical solutions in the field of science. (Miettinen et al., 2022; van Wyk et al., 2022.)

During this process of mapping the cartographies, some interesting occurrences emerged. At first, the surface of blood textiles conveyed an idea of ice dying patterns, which, with the use of ice or snow, create vibrant and crackling surface patterns (see Fig. 4). Afterwards, without any forced intention, the results of the textile image had a clear resemblance with the works of art of one of the greatest Finnish-Lappish artists in the entire history of Finland, Reidar Särestöniemi (1925–1981). Särestöniemi developed his own specific colour expressionism based on using different materials, scratching the surface, using colours in a new way and working in a more spontaneous style based on arctic nature and the unique colours of eight seasons. For example, Huurrekoivikko (Birches in Rime Forest, 1969), oil on canvas, expresses how Särestöniemi paints birches in hoarfrost with the glimmer of the sun. A glittering lichen-covered birchbark surface in a snowy fen or forest with a cold and reddish sky on the horizon conveys the idea of winter. (Hautala-Hirvioja, 2019, p. 106-107; Särestöniemi et al., 2008, p. 89, p. 129; Aalto, 1976, p. 38). His overwhelming use of colours in his works of art depicted his passion and understanding of unusual cartographic margins.

Interestingly, reindeer blood, which was experimented without any intention of being inspired by the Lappish artists’ work, was eventually beheld as if it were a true inspiration right from the beginning of this artistic process. One possible explanation for this can be found in that unintentional and unconscious inspiration existed in the minds of the artist-researchers before it was even experimented with. Although this only emerged when it was recognized as one of the layers of the artistic process, just like Särestöniemi’s art, the work has multiple layers to convey the idea of materiality.

To begin with, the visuals show the potential boundaries and mapping of different possibilities on their own. This is one of the many prospects that can be interpreted though these textiles. All of these makings have the tendency to interpret the artistic goal. Leavy (2017, p. 517) stated that ‘All research requires interpretation; even results from statistical measures need to be interpreted.’ It is, therefore, the process of moving back and forth between layers of data that assists the artist in interpreting and answering critical research questions.

A digital printed fabric design process involves many translations that move from analogue to digital and back: translating collected data (arctic raw materials: reindeer blood, paintings, photos) via digital software into colours, images and patterns (e.g. points, lines, surfaces), planting these in a digital environment, and making these digital images material again through printing (Grant et al., 2021). What do we gain and lose in these translations? The delay and depth associated with time, space and place disappear in digital images and surfaces. The volume does not even refer to the measure of digital printed fabric, as narratives are hidden in the flatness of a painted surface. It is more of an activist approach during the process of interpretive artistic creation, as the authors of this study strive to be radical, to seek something new and to integrate natural environments, which can eventually lead to power knowledge. Additionally, this entire process can be classified as a collaborative art installation, which deals with questions of representation and their relation that involves forms, materials and practices (Dumitriu, 2019).

Creating artworks that contribute new research questions and pioneering technologies is key to the critical engagement of bioart. This can address the challenges to emergent life science research, which can identify significant findings across a broad research spectrum of life sciences. It can also stimulate scientific knowledge, artistic practices and methods for creating artwork that contributes to new research questions.

In-Between Space

Exploring the experiential qualities of reindeer blood (material) brought to the attention the role of materials in affecting our ways of thinking, including knowledge and data from ABR. Reindeer blood research has translated our subjective experiences of materials into data. It has evoked a discussion of how blood as a material could be seen as an actual correspondence before the final form-giving to an object, whether this form-giving is material or immaterial. Reindeer blood as a design tool and material places the sketches and experiments in the ‘in-between space’ between temporary and durable surface pattern designs (see Walker, 1989, p. 193-195).The workshop approached a living organism, a reindeer blood, both as a medium and as subject matter, involving it in the creation of artistic acceptance for these bioart developments and processes (Griniuk et al., 2022, p. 44-45).

Bioart as a pluralistic practice brought the artist-researchers to consider their ethical standing. This means that designing is not only about producing visual traces of microbes or surface pattern design. From the very beginning, the process expressed the relationship between the human experience and a living design medium (reindeer blood) that has its own agency. In line with contemporary trends in bioart, this offers up possibilities of source of inspiration, raw material, shared experiences, collaborative practices, cooperation and shared authorship.

Many artist-researchers, such as Pietarinen and Qureshi, are moving away from conventional materials, methods and laboratories to explore new innovations in art, design and science. For example, their work includes microbial data and art practices that work with nature and textiles (Härkönen et al., 2023; Grant et al., 2021; Kapsali, 2016, p. 15-16; Qureshi, 2022). Their artistic creations express the idea that nature is experienced via many life forms and co-creators rather than as a collection of mere objects. Consequently, the crucial question arises: What might an artist-researcher's relationship with nature be like? In the upcoming 2023–2024 workshops at the University of Lapland BioArtTech laboratory; art galleries in Rovaniemi, Finland; and conference and exhibition in Loughborough University, London, Pietarinen’s and Qureshi’s ongoing works will come to life, disseminating research concepts based on a living design medium (reindeer blood), other arctic raw materials and natural resources for bioart.

References:

Aalto, E. (1976). Reidar Särestöniemi. WSOY.

Ballardini, R., M., & Casi, C., 2020. Regulating Nature in Law Following Weak Anthropocentrism: Lessons for Intellectual Property Regimes and Environmental Ethics. Retfærd: nordisk juridisk tidsskrift,167(4), 17–38. http://hdl.handle.net/10138/328947

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press.

Benyus, J. M. (2002). Biomimicry: Innovation inspired by nature. Perennial.

Berger, E., Mäki-Reinikka, K., O’Reilly, K., Sederholm & Schmidt M (2020). Art as We Don’t Know It. First edition. Aalto University.

Camere, S., & Karana, E. (2018). Fabricating materials from living organisms: An emerging design practice. Journal of Cleaner Production, 186, 570–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.081

Connor, K. (2023). Projects. https://www.katyconnor.net/projects

Corby, T. (2014). Blood and Bones. University of Westminister. https://westminsterresearch.westminster.ac.uk/item/q2wy8/blood-and-bones

Csikszentmihalyi, M., Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Sawyer, K. (2014). Creative insight: The social dimension of a solitary moment. The systems model of creativity: The collected works of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, 73-98.

Dumitriu, A. (2019). Collaborative Journeys in Art and Biology. In A. de la Garza & C. Travis (Eds.), The STEAM Revolution (p. 97–105). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89818-6_7

Dumitriu, A. (2023). The Birth of Snowflake. https://annadumitriu.co.uk/portfolio/the-birth-of-snowflakes/

Essaïdi, J. (2021). Designers should "equip nature with the diversity of trash it needs to work its magic faster" says Jalila Essaïdi. https://www.dezeen.com/2021/11/11/dezeen-15-jalila-essaidi-designers-equip-nature-diversity-trash/

Grant, M., de Peyer, O., Imlach, H., Pietarinen, H., Bovermann, T., Yoncha, A., & Sandgren, N. (2021). High Altitude Bioprospecting, Atmospheric Encounters, https://h-a-b.net/ExpeditionsandExhibitions/atmospheric-encounters-2021

Griniuk, M., Akimenko, D., Miettinen, S., Pietarinen, H., & Sarantou, M. (2022). Multiperspective take on pluriversal agenda in artistic research. In S. Miettinen, E. Mikkonen, M. C. Loschiavo dos Santos & M. Sarantou (Eds.), Artistic Cartography and Design Explorations Towards the Pluriverse (pp. 40–54). Routledge.

Guttorm, S., (2022). Porojen teurasjätteitä menee paljon hukkaan – hyödyntäminen vaatisi mittavia investointeja (A Lot of Reindeer Slaughter Waste Is Wasted - Utilization Would Require Considerable Investments). Yleisradio (Finnish Broadcasting Company). https://yle.fi/a/3-12682063

Hautala-Hirvioja, T. (2019). Reidar Särestöniemi: Life in Lapland and Inspiration from Arctic and Northern Nature. In M. Mäkikalli, Y. Holt & T. Hautala-Hirvioja (Eds.), North As a Meaning in Design and Art (pp. 94–108) Lapland University Press.

Higgins, J. M. (1994). 101 creative problem solving techniques: The handbook of new ideas for business. New Management Publishing Company Inc.

Hoyos, C. M., & Fiorentino, C. (2017). Bio-utilization. The International Journal of Designed Objects, 10(3), 1–18. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18848/2325-1379/CGP/v10i03/1-18

Härkönen, H., Ballardini, R., Pietarinen, H., & Sarantou, M. (2023). Nature’s Own Intellectual Creation: Copyright in Creative Expressions of Bioart. NuArt Journal 4 (1 Issue) 7, 100–110. https://nuartjournal.com/pdf/issue-7/11_NJ7-Harkonen.pdf

Jain, M. (2014). Environmental Biotechnology. Alpha Science International Ltd.

James (2022, Nov 11). 10 Fun Facts about Reindeer. Finland Portrait. https://www.finlandportrait.com/facts-about-reindeer/

Kanwal, N., & Awan, U., (2021). Role of Design Thinking and Biomimicry in Leveraging Sustainable Innovation. In: Leal Filho, W., Azul, A.M., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Wall, T. (eds) Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. https://lutpub.lut.fi/handle/10024/161788

Kapoor, A. (2022). [Exhibition]. The Gallerie dell’Accademia di Venezia. Venezia, Italy. https://www.gallerieaccademia.it/en/anish-kapoor

Kapsali, V. (2016). Biomimetics for Designers: Applying Nature’s Processes and Materials in the Real World. Thames & Hudson.

Karana, E. (2010). Meanings of Materials. LAP LAMBERT, Academic Publishing.

Karana, E., Barati, B. Rognoli, V., & Zeeuw Van Der Laan, A. (2015). Material driven design (MDD): A method to design for material experiences. International Journal of Design, 9(2), 35–54. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277311821_Material_Driven_Design_MDD_A_Method_to_Design_for_Material_Experiences

King, A. (2019). Bio‐art: A fusion of biology and art both raises awareness of and challenges science. EMBO Reports, 20(7), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.15252/embr.201948563

Koskinen, I., Zimmerman, J., Bindet, T., Redstöm, J., and Wesveen, S. (2012). Design Research Through Practice. From Lab, Field and Showroom. Morgan Kaufman.

Kääriäinen, P. (2021). Muotoilu ja tiede kohtaavat materiaalikehityksessä. In Muotoilun avaimet: älykkääseen teollisuuteen ja liiketoiminnan ketterään kehittämiseen (Design and science meet in material development. In Design keys: for smart industry and agile business development). Ed. Satu Miettinen. S. Teknologiainfo Teknova Oy, 133–143.

Lahelma, A. (2008). A Touch of Red Archaeological and Ethnographic Approaches to Interpreting Finnish Rock Painting. Suomen Muinaismuistoyhdistys ry - Finska Fornminnesföreningen rf The Finnish Antiquarian Society. The Finnish Antiquarian Society.

Leavy, P. (Ed.). (2017). Handbook of arts-based research. Guilford Press.

Lewis-Williams, J.D. (2002). The Mind in the Cave: Consciousness and the Origins of Art. London, Thames & Hudson.

Luho, V. (1971). Suomen kalliomaalaukset ja lappalaiset. In Vanhaa ja uutta Lappia (Finnish rock paintings and Lappans. In Old and new Lapland). Kalevalaseuran vuosikirja 51, WSOY, 5–7.

Mattila, N., (2019). Poroteurastamon sivutuotteiden hyödyntäminen Sallan malliin (Using the by-products of the reindeer slaughterhouse in Salla’s model). In K. Majuri & K. Muuttoranta (Eds.), Poroteurastuksen kehittämisen painopisteet (pp. 27–30) (The Priorities of the Reindeer Slaughter Development). https://www.virtuaaliteurastamo.fi/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Poroteurastuksen-kehittamisen-painopisteet.pdf

McNiff, S. (2014a). Art speaking for itself: Evidence that inspires and convinces. Journal of Applied Arts and Health, 5(2), 255–262.

Muje, P., (2019). Poroteurastuksen sivutuotteet osana kestävää liiketoimintaa (Reindeer Slaughter By-Products as Part of Sustainable Business). In K. Majuri & K. Muuttoranta (Eds.), Poroteurastuksen kehittämisen painopisteet (pp. 23–26) (The Priorities of the Reindeer Slaughter Development). University of Lapland University of Applied Sciences. https://www.virtuaaliteurastamo.fi/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Poroteurastuksen-kehittamisen-painopisteet.pdf

Parasta poroa -koulutushanke (The Best Reindeer Educational Project). (2023). http://parastaporoa.blogspot.com/.

Parsaee, M. & Demers, Claude M.H. & Hébert, M. & Lalonde, J-F. & Potvin, A., (2019). A photobiological approach to biophilic design in extreme climates. Building Environment, 154, 211–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.03.027

Patoreau, M. (2016). Rosso, storia di un colore. Ponte alle Grazie.

Pietarinen, H. (2019). Textile Designers’ Travels and Northern Beauty: Marianne Strengell and Marjatta Metsovaara. Mäkikalli, M., Holt, Y., Hautala-Hirvioja, T., & Blond, A. In North as a meaning: In design and art (pp. 109–120). Lapland University Press.

Pietarinen, H. (2021). Reddish Orange – Ruskie. In Documents of Socially Engaged Art. Ed. Melanie Sarantou, Raphael Vella. In SEA. DocumentsOfSociallyEngagedArt_web.pdf (insea.org)

Pietarinen, H., Miettinen, S., & Sarantou, M. (2022a). Biotaidetta tarkasteleva laboratorio (A laboratory examining bioart). Tahiti, 12(3), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.23995/tht.121885

Pietarinen, H., Timonen, E., & Sarantou, M. (2022b). Reindeer in Sapporo and Shanghai: Materiality as a Mediator of Empathy Through Culture-Based Design. In Empathy and Business Transformation (p. 212–227). Routledge.

Qureshi, A., Sarantou, M., & Miettinen, S. (2022). Meaning-making and interpretation through personal mandalas in the context of visual literacy. Journal of Visual Literacy, 41(3–4), 247–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/1051144X.2022.2132625

Raffaelli, Q., Malusa, R., de Stefano, N. A., Andrews, E., Grilli, M. D., Mills, C., & Andrews-Hanna, J. R. (2023). Creative Minds at Rest: Creative Individuals are More Associative and Engaged with Their Idle Thoughts. Creativity Research Journal, 1-17.

Rauhala, O. (2017). Osmo Rauhala: peilitesti (Osmo Rauhala: A Mirror Test). In O. Rauhala & M. Didrichen (Eds.), Didrichen Art Museum.

Rauhala, O. (2021). Osmo Rauhala: Muista unohtaa kaikki (Osmo Rauhala: Remember to Forget Everything) [Exhibition]. Aboa Vetus Ars Nova museum.

Reindeer Herders' Association. https://paliskunnat.fi/reindeer-herders-association/

Røstvik C. & MacDonald, N. (2019). Annual Conference Blood in Modern and Contemporary Art. https://forarthistory.org.uk/conference/2019-annual-conference/blood-in-modern-and-contemporary-art/

Sonneveld, M. H., & Schifferstein, H.N.J. (2008). The tactual experience of object. In H. N. J. Schifferstein & P. Hekker (Eds.), Product Experience (p. 41–67). Elsevier. DOI:10.1016/B978-008045089-6.50005-8

Stahl, P.W. (1986). Hallucinatory Imagery and the Origin of Early South American Figurine Art. World Archaeology, 18(1), 134–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1986.9979993

Särestöniemi, R., Kokkonen, J., & Hautala-Hirvioja, T. (2008). Reidar Särestöniemi: arktisia elementtejä = arctic elements. Levin luontokeskus (Levi Nature Centre).

The Sámi Education Institute. (2023). Foundation of Skillfull Tradition. https://www.sogsakk.fi/en

van Loon, J. (2023). Cellout.me. https://jeroenvanloon.com/cellout-me/

Walker, J. A. (1989). Design History and the History of Design. Billing & Sons.

Wastl-Walter, D. (2016). The Routledge Research Companion to Border Studies (First edition.). Taylor and Francis, an imprint of Routledge.

Yleisradio Oy. (2016, October 20). Tapio Wirkkala: The man who designed Finland. https://areena.yle.fi/1-2820400