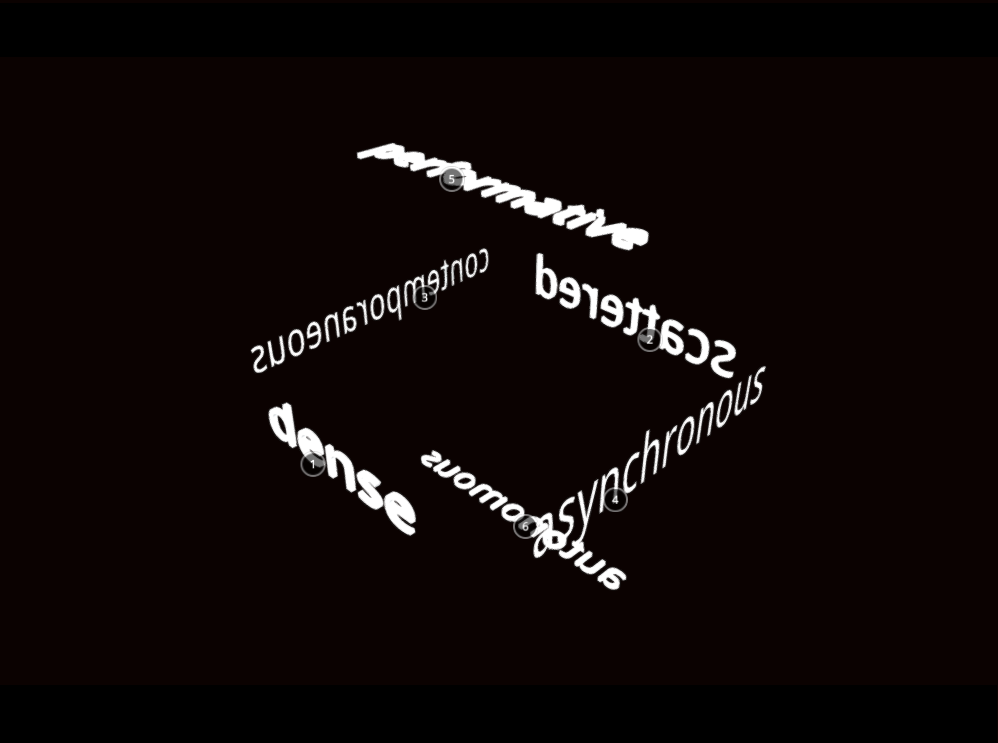

The different formations of audience bodies are linked to conventional aesthetics of different topical artistic genres. Audience bodies invoked by literature are typically scattered (not in the same space), asynchronous (not at the same time) and fairly autonomous (only lightly complicit to the appearance of the artwork). Audience bodies invoked by fine arts are typically dense (in the same space), asynchronous and a bit less autonomous. Audience bodies invoked by theatre are typically dense (in the same space), contemporaneous (at the same time) and performative to some extent (the members of the audience body become visible to each other and they have an effect on the artwork itself).

Subordination to a performance

In the occidental context of art, an audience is invoked by a performative act. It may be the voice of a street performer inviting passers-by to watch or the opening of a ticket sale for a theatre season. Procedurally, a performance comes first and attracts the attention of an audience to come and perceive it. This order is due to the difference in preparation—the makers of an artwork and its audience differ in the amount of preparation they engage in. The asymmetric relation between those who are more prepared (the makers) and those who are less prepared (the audience) continues throughout the event as the resonant position of the audience demands from them a deferral of action. An audience body abstains from excercising much of the agencies it would have at its use would it not identify as an audience body. Agency is replaced by resonance.

An audience is dependent on the performative and self-interested acts seeking their attention. Joan Didion claims that writing is an “aggressive, even a hostile act”, “a tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the writer's sensibility on the reader's most private space” (Didion 2021, 45-46). Almost echoing Didion’s words, Antti Nylén states that “all speech and use of language—and especially literature—is produced by an agitated and loaded mind.” The writer is an “obnoxious character who barges in front of by-passers, tries to stop them and make them into recipients of the message.” (Nylén 2018, 140-41, my translation) I would generalize this proposal to include all acts of making art. They invade, colonize and insist on attracting attention. They do not accept things as they are and offer themselves as the change. Resonance by contrast is an acceptance of these aggressions and a way to extend their zone of influence and life span. For example, in Selfie Concert, performance artist Ivo Dimchev walked onstage like a seemingly distracted diva and started to sing in a heavenly voice. He then told the audience that we should take selfies with him constantly, at least three of us at a time, or else he would stop performing. Dimchev took hold of the audience and dominated it with sovereignty with this simple gesture and his powerful charisma (Selfie Concert 4.2.2020).

An audience is thus procedurally subordinate to a performance, even if there is a complex power structure at play at the same time. Procedural subordination does not imply a value judgement. This dynamic is regulated by the distribution of complicity between the makers and the audience. The makers are always the most complicit with regard to the appearance of an art work, while the degree of complicity of the audience varies. If the complicity of the audience grows far enough, the precondition of subordination, and simultaneously the phenomenon of audience, evaporates. Beyond the limits of an audience body lie the agential realms of community, ritual participation and artistic makership. If an audience body would start to identify itself as a ritual community, it would gain so much agency and responsibility that it would lose its subordinate relation to the performance.

Gathering

An audience body is by default plural. This plurality is created through an act of gathering. This act is paradoxical since it results in a (partial) renunciation of the participants’ possibility to act. Gathering is here understood in a wide sense, following Dorothea von Hantelmann’s use of the term. Von Hantelmann calls the formation of audience bodies in theatre, based on the format of an appointment, collective gatherings and their formation in galleries, based on the format of opening hours, individualized gatherings (Hantelmann 2019, 254). In the framework of this research, all forms of art gather people to attend specific artworks, but the density and synchronicity of the audience bodies gathered vary according to the chosen media. The more scattered and asynchronous the audience body, the thinner our experience of its existence can be. The more conscious the members of an audience are of each other, the more embodied their collectivity. Due to this, performing arts are the genres where audience bodies are most actual and available to be perceived and experienced.

During the research process, the prohibition of onsite gatherings due to Covid-19-epidemic in 2020 emphasized the effects of audience bodies gathering in actual places and their radical difference from gatherings in remote formats. In my case, the performance Odd Meters by Mikko Niemistö in September 2020 was revelatory. After living six months more or less in a lockdown it was stunning to experience Niemistö’s body sweating, gasping for breath, exhausting itself almost at an arm’s length before us and resonating in our masked collective body. (Odd Meters 2.9.2020)

Also performances for an audience of one fit within this inclusive definition of gathering. An exception to the rule would be artworks which are truly attendable by only one person in total—and even they may be haunted by the inexistent plurality of their audience.

Resonance

When a sound source sends a vibration through a transmission medium such as living tissue, this medium may start to resonate: to re-sound, sound again, sound back. The same would apply for other kinds of vibrations such as electromagnetic waves or emotional reactions. If a collective body is formed and it reserves some of its agencies to be attentive to a performance, it is open for potential resonances. The energy that would otherwise be used for action is deferred and instead the body is offered as a material basis for resonances that are a consequence of the performance attended.

Researcher Gunnar Bäck also uses the term energy to account for the way audiences condition performances and proposes that “the expectations of the spectators possess a tangibility that approaches materiality. They “charge” the scene and form what can be called an energy field, to which the actor must find an approach: he can only touch his audience when he “responds” to their expectations” (Bäck 1992, 27, my translation). My view is that the energy field is layed out and charged through the active submission of the audience. Resonance does not imply a total disappearance of agency, rather it is an underlying modality that defines an audience body. A resonant body is under the influence by choice. It is not merely an independent, distanced receiver of a message but through being a transmissive medium it merges with the message, becoming at the same time an accomplice and a victim, a semi-ignorant para-artistic conspirator.

Liminoid dramaturgy

Audience bodies are loose and temporary composites, joined by their members for the duration of an artwork. Participation to these temporary bodies requires a suspension of self-determined behaviour. One has to let go of individual choice to some extent. Another feature of taking part in audience bodies is the expectation of a transformation. Taking part suggests a wish to experience something unexpected, impressive or powerful; to be changed by the experience. If this expectation or desire would decrease, the complicity of the audience would decrease as well.

The process, in which audience bodies gather, persist and disperse, can be described well with the conceptual frame of liminality. It was introduced in relation to rites of passage by folklorist Arnold van Gennep in early 1900s, developed further by anthropologist Victor Turner in 1960s and utilized in the context of performance studies by Richard Schechner. Turner presents van Gennep’s theory like this: rites of passage are composed of three dramaturgical phases—preliminality, liminality and postliminality. A participant of a rite first separates from the everyday life of the community, enters an ambiguous liminal state outside of society and then is reincorporated into the society transformed. (Turner 2007, 106-10) While audience membership does not typically carry a weight comparable to rites of passage, it follows a similar dramaturgical structure, in the central phase of which social rules that govern the everyday are partly suspended. Tom Selänniemi, who has studied the phenomenon of tourism using Turner’s ritual theory, explains how Turner calls these kinds of light-weight liminal experiences quasiliminal or liminoid (Selänniemi 1999, 277). Richard Schechner adds that in general liminal activities are compulsory, liminoid ones voluntary, categorizing art as liminoid (Schechner 2016, 120). Thus I have termed the temporal progression of a liminoid experience liminoid dramaturgy. I have also used the term ritualesque to account for the “light” liminality at play in an audience body.

Samuli Laine’s and Reality Research Center’s Nurture guided the sole audience member through an experience of being breast-fed by the artist. The preliminoid phase consisted of waiting in the corridor, entering the performance space and being instructed by the performer of how the performance would progress. It also contained some preparatory actions such as taking off my shoes and washing my hands. Then I took his artificial nipple in my mouth and entered the liminoid with my eyes closed, drifting into other-worldly realms composed of bodily sensations, remembrances, imagination and intimacy. Then the performer would escort me back with a postliminoid dramaturgy of returning to my performative everyday self with my social roles and conformist behaviour. We discussed the experience a bit and I put my shoes back on, redressed my outdoor clothing and the stepped out of the room. (Nurture 22.11.2021)

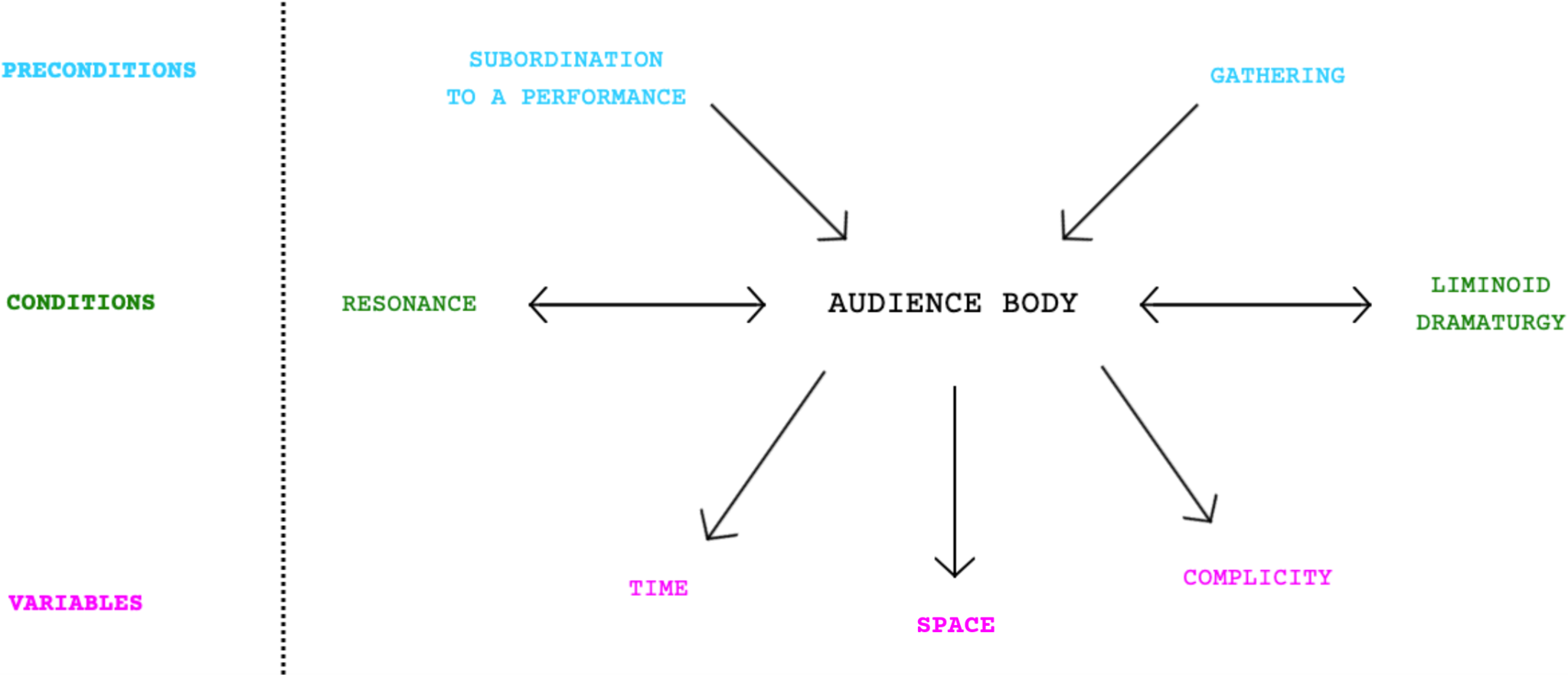

This system of differentiating audience bodies is based on a multipolar and cubic structure that is composed of three variables stretching between three pairs of opposites, represented by six faces of the cube (visualized in the link opening from the image below). Each of these pairs forms one dimension of the cubic structure, situating any audience body somewhere on an axis which contains the gradients of that particular variable. Any position in the cubic structure is not in a general sense more valued than other positions; they are however different in quality. This rejection of ontological differences between forms of art is akin to Philip Auslander’s definition of liveness, which addresses the temporal and spatial varieties, as well as varieties in the distribution of agency, in live situations (Auslander 2023, e.g. 27-35). Due to the difference in quality positions can become differently valued when viewed from a specific angle. For example, the positions that are most valuable to my work are those which create more actual, perceptible and intense audience bodies. The faces of this metaphorical cube are flexible and porous: there are no pure examples of any extremity of the system, though some examples may illustrate well the far sides of the variables.

Click the image below for the 3D diagram. Clicking the numbers in the diagram opens short descriptions.

Two faces of time

An audience body can be contemporaneous or asynchronous with itself. A contemporaneous audience body is composed of members who attend an artwork at the same time. This is typical for all forms of performing arts and live broadcasts. Philip Auslander elaborates on how early television challenged theatre as a new form of liveness, specifically due to the contemporaneity of performances and their reception: “Unlike film, but like theatre, a television broadcast is characterized as a performance in the present” (Auslander 2023, 36). Contemporaneity affords an audience experiences of its collective embodiment, resulting in different types of group behaviour and social control. For example choreographer Mia Habib gathered a large and versatile group of non-male performers to realize a simple repetitive choreography All—A Physical Poem of Protest in the town of Jyväskylä in Central Finland. It took place outdoors, on a rainy October evening. The performers, who were of different ages, repeated simple patterns of movement in a circular form. I was struck by the realization that the audience body, of which I was a member, had gathered just to experience this repetition, standing persistently in the dark and rainy square with our aging bodies witnessing the endless movements of those other aging bodies. (All—A Physical Poem of Protest 1.10.2022)

Asynchronous audience bodies attend the same work at different times. This is typical for example for exhibiting works of fine art, literature and the majority of internet-mediated art. Asynchrony affords the members of an audience a possibility to make individual choices with less social pressure, for example with regard to the amount of time they use to attend the work. Simultaneously, it compromises the coherence of an audience as a body and can make it very difficult for the members of the audience to experience the presence of the collective body before which the work is placed. Still, asynchronous collective audience bodies can also be experienced due to appropriate artistic choices on behalf of the makers and/or parapractical experience on behalf of the audience. The fifth episode of In Search of Lost Time 2017-2027, a long series of performances by Aleksi Holkko and Hanna-Kaisa Tiainen staging Marcel Proust’s magnum opus piece by piece, was realized in 2021 during the Covid-19-epidemic in the format of a letter to be opened and read in any graveyard. It was built to be experienced at any time after one had received the letter by post. However, the expectation of the makers seemed to be that the audience would experience it during some weeks or months in the spring 2021, shortly after receiving the letter. I opened the letter three years later, in 2024 and yet my experience of an audience body was not compromised, I still felt I was a part of it. (In Search of Lost Time, part 5) In comparison, gustaf broms performed untitled (worlds of becomings) for 40 hours in a commercial space on a shopping street in Turku in September 2023. I visited the space several times during those 40 hours, at different times of the day and night. Sometimes I was there alone, sometimes there were others, sometimes it attracted the attention of drunken teenagers passing the site. Some people would just glance at it, some would stop to watch through the window, some would come in, some would stay for hours. (untitled (worlds of becomings) 7.-8.9.2023) Both these examples enable also synchronization. The longer the duration of the availability of the work, the more asynchronous audience bodies it affords. If the duration is years, centuries or even millennia, the experiential variety within the audience body can be extensive, as its members may live in completely different circumstances.

Two faces of space

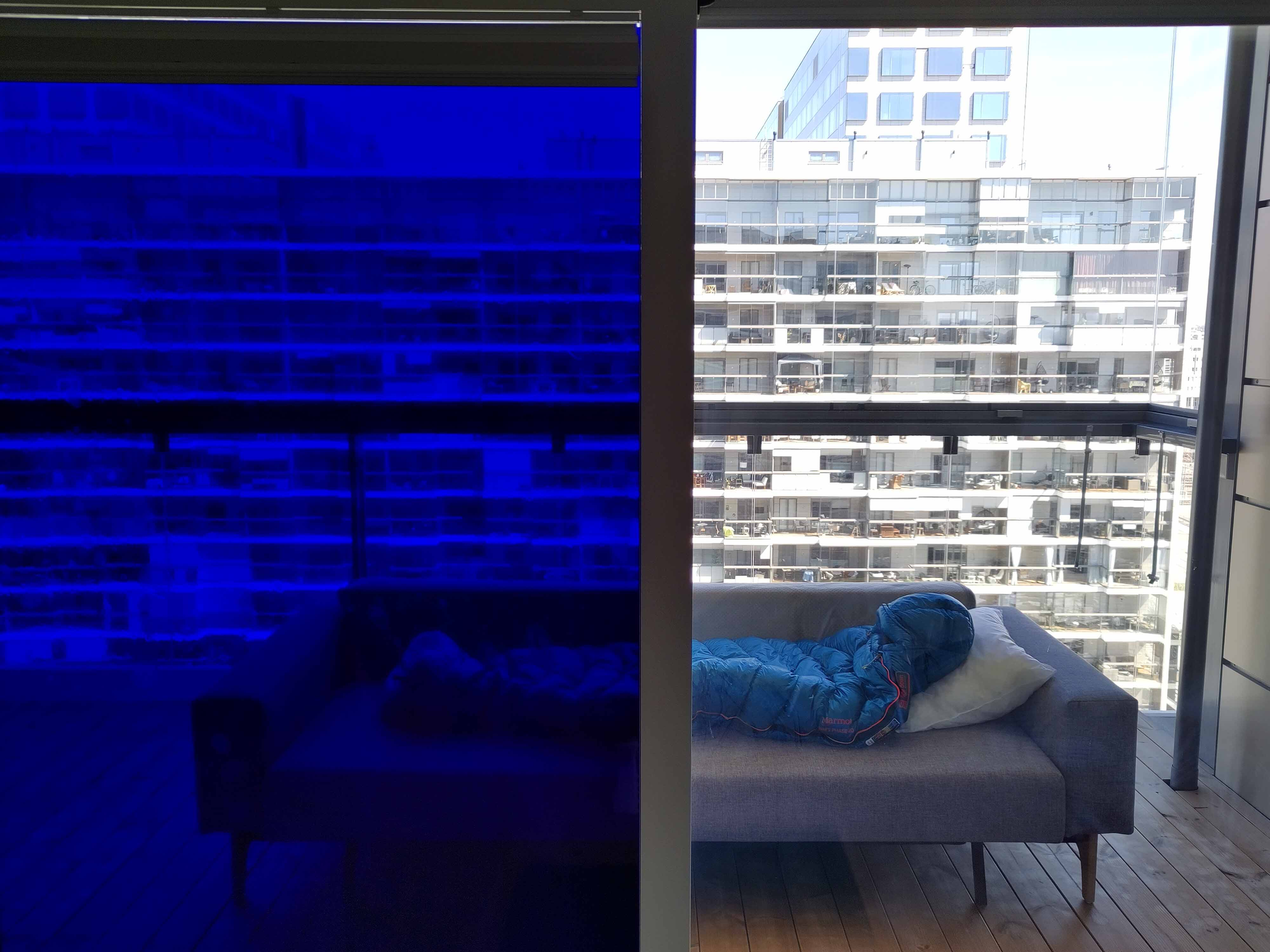

An audience body can be spatially dense or scattered. A dense audience body is composed of members who attend an artwork in the same place. This is typical for performing arts as well as to exhibition practices of fine arts. Like contemporaneity, density affords an audience experiences of its collective embodiment, as well as perceptual alignment: the access to the same environment, with all its sensuous qualities, enables experiential connections between audience members. For example artist duo Biitsi built their performative installation Silver Medal into an apartment in connection with the shopping center Tripla in Helsinki. The work dealt with aging, memory loss and family ties. The apartment was furnished with artworks donated to Biitsi by their friends as well as documentation of the artists making art with their aging relatives. The windows were coated with blue film, creating a eerie and calm atmosphere to the room. Audience members could book a 30 minute visit and each timeslot was open for few members. The audience body thus was (or the audience bodies were, depending on interpretation) temporally stretched out over several days, combining formats of opening hours and appointment. What forged an audience body together was the designed space that they were able to visit. (Silver Medal 19.5.2022)

Scattered audience bodies attend the same work in different places. This is typical for example within the genres of literature, film, television, recorded music and internet/social-media-based art. Like asynchrony, scattering affords the members of an audience body individuality and less social pressure. It also compromises the coherence of an audience as a body. If scattering is coupled with contemporaneity, as with broadcast television, the audience body can be aware of its own presence even if the other members are not within their range of perception. Performances that summon scattered audience bodies proliferated during the pandemic. For example Ontroerend Goed’s TM was realized as multiple simultaneous interview meetings between a performer and an audience member in a video call application. A ticket for the same show could be purchased from several theatres that were situated in different countries, creating a multinational audience body situated across continent(s). In the end the audience members were made aware of each other's contemporaneous presence as a collective audience body by showing the faces of all participants on the screen view of the conference call (TM 22.4.2021).

Two faces of complicity

An audience body can be more or less complicit to the emergence and endurance of an artwork, ranging from the minimally complicit autonomous audience body to the highly complicit performative one. Complicity requires contact between a performative act and an audience body—through contact the agents of the performance can be influenced by the resonance taking place in the audience body. The less contact there is between the making of the work and other ways of attending it, the more autonomous both modalities are with respect to each other. The resonances within an audience body do not in this case reach the process of making (although they might be part of a bigger cycle of resonance and affect the following works by the same makers). The more the resonances emerging within the audience body are able to affect the process of making, the more performative the audience body becomes. If the performativity of the audience grows strong enough, their function as a resonant body becomes compromised and they may lose their ability to identify as an audience. This is a balance with which artists often engage: they wish the audience to resonate with their work without compromising the subordinate position of the audience body (or their experience of safety). The criminal implications of the term complicity refer to the controversial nature of safety in the context of art. Contemporary occidental art is prone to destabilizing and disturbing the audience to achieve an effect; the elements of danger and non-normativity are necessary for its relevance. To be completely safe and conformist would strip it of its attraction and relegate it into the category of entertainment; to threaten the safety of the audience body excessively would also eventually situate it beyond the definition of art.

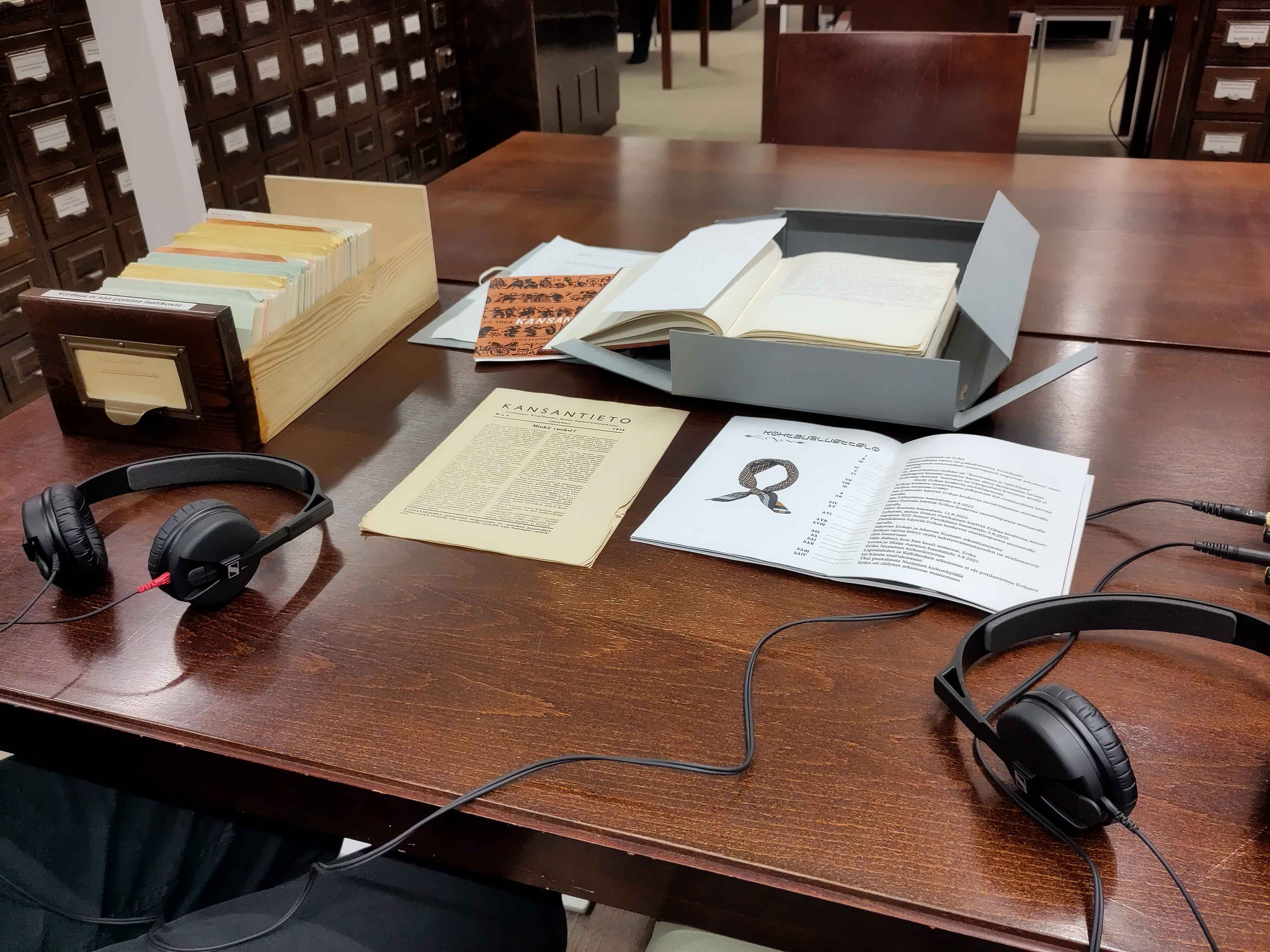

The complicity of an audience body is minimal when they have no effect on the formation of the work, do not engage in a dialogue of any kind with the work or its makers and they need to do a minimum amount of physical, affective or intellectual labour to take part. The audience body is then autonomous—it is as free as possible from the resonant, interdependent feedback loop between performers and their audience. This would be the case for example with conventional television shows that prioritize entertainment values. On a more general level, for example the genres of literature and film demand a low amount of complicity from their audiences. Artworks of these genres can exist regardless of whether audience bodies are formed or not—they are almost independent from the resonance of actual audience bodies, even if potential and imagined audience bodies may affect the creative process of the makers. This low-level complicity, along with enduring materials or reproductability, affords audiences access to artworks from different ages, as well as the possibility to revisit the works. For example Simon Vicenzi’s FROM THE DEAD AIR ORGY: On the Nature of Things was presented in the programme of the Mad House Helsinki during the pandemic as a partially live video feed via the Internet. Some parts of the work had been filmed in advance, while others took place and were filmed live, contemporaneous to airing it. My experience of attending it as an audience member was troubled by my knowledge of this fact. I knew that it was not all live, but I could not distinguish the parts that were. I did not understand the reason for the contemporaneity of the audience body as it did not seem to give any extra value to the experience. What was the point of my presence and why could it not only have been attended like any film? It seemed like my complicity was asked for but it did not actualize in any way. (FROM THE DEAD AIR ORGY: On The Nature of Things 12.10.2021) Emil Santtu Uuttu’s The Lovely Daughter Erika—Notes on a Name took place in the archive of the Finnish Literature Society. It could be experienced either alone or together with another person. The audience members were guided to a table, upon which there was an audio player and an archive folder. The work consisted of an audio play, which included printed and archival materials found in the folder as well as a video epilogue. If Vicenzi’s work would exist even if we were not there to attend it, Uuttu’s would not, which rendered us complicit. I had no means to affect the video feed in any way, but the materials in the folder needed my input to perform the work. Also, the dynamics between myself and the other audience member next to me became a part of the experience of the work. And yet, there was something literature-like in the work. Like a book, the work was what it was and it could not fail one day and succeed on another (which would be the case with a live performer). (The Lovely Daughter Erika—Notes on a Name 6.11.2023)

The complicity of audiences increases when we move towards contemporaneous and dense formations of audience bodies, like the two bodies sitting next to each other in the Finnish Literature Society's archive. When an audience appears in a theatre—with all its members in the same place at the same time—they are inevitably complicit, regardless of the quality of their engagement, since the performers can feel the resonance taking place in the audience body. Similarly, if the work is participatory, the complicity of the audience body increases. When contemporaneity, density and participatory aesthetics are combined, the complicity of an audience body is high. This would be the case with performing arts that experiment with the role of their audience. Complicity affords both the makers and the audience an intensified experience.

In DOWN BEAT BEAT DOWN BEAT DOWN DOWN BEAT by the artist duo Mean Time Between Failures the performers offer their audience bubble gum at the beginning of the performance. They also have some themselves and encourage us to have more when we need during the performance. Everyone chews on their gum throughout the show, creating a collective choreography of jaw movement, saliva production and humour. In a later part of the event the performers ask us to place our chewed gums on their naked skin. The audience body takes part in performing the series of gum actions. Our bodily liquids on the bodies of the performers render us inevitably complicit on a very material level. (DOWN BEAT BEAT DOWN BEAT DOWN DOWN BEAT 11.5.2024)

Participation can be defined as the disclosure of the complicity of an audience. If we take a theatre play as an example where audience is seated silently in a non-lit auditorium, their presence has a strong effect on the events on stage. However, the audience members would not most likely consider the work participatory, since this form of complicity is trivial and almost unnoticeable due to its conventionality. If a light is then directed towards the auditorium, the complicity of the audience is disclosed and the work becomes participatory. If we are then asked to chew on a gum and press it on the skin of the performer, our participation is placed on display in an unpretentious way and the audience body is rendered performative. The non-disclosure of complicity is also related to an expectation of anonymity. Anonymity protects audiences from becoming aware of or performing their complicity as well as from compromising their resonant function. One can be totally anonymous when listening to the radio at home, quite anonymous when sitting in a dark auditorium and partly anonymous when witnessing a performance in a fully lit gallery where the faces of everyone are visible. It is very rare that the names of audience members are used or publicized in some way.

To conclude

Contemporaneity, density and complicity enable the appearance of audience bodies. The more asynchronous, scattered and non-complicit an audience is, the less it can be experienced or even conceptualized as a body. The thinner the force that binds it together the more imagination is required from us to believe in its existence. Because of this, the phenomenon of audience bodies has a special relationship to performing arts. If, on the other hand, an audience becomes so complicit, that its subordinate relation to the performance becomes compromised, the asymmetricity and tension characteristic to an esitys/beforemance evaporates and as a result the audience body changes into something else.

The Finnish genre of esitystaide/beforemance art is linked to complicity in a fundamental way. In my framework, performances claim territories of reality through invasive acts. When they are conceived as components of beforemances, with resonant audience bodies as their polar counterparts, this conquest turns into complicity.