I started my research with the question “what is an audience?” Through the practice, I re-iterated the question to address the audience body: if audiences are defined as collective bodies, what does that mean and how do these bodies form? And since I was conducting artistic research in the context of the genre of esitystaide, I further asked: how to address the phenomenon of the audience body in the contexts of esitystaide and artistic research? Chapter 4 exposes how I encountered these questions in practice and how the proposals made in Chapter 2.2 developed via the variety of ways audience bodies were produced and formed in my experiments. Here, in order to introduce the concept of the audience body, I will address some histories and sources that are relevant, but which are not straight-forwardly practice-based.

Terminologically, I started the research project with spectator, then quickly opted for audience, from which I have by now moved on to speak about audience bodies. Throughout my research I have been using the English word audience and the Finnish word yleisö side by side, as reciprocal translations. They are generally used in a similar way, although their etymologies and implications differ, which I will elaborate more below. Audience bodies have not to my knowledge been thematized like this before, but audiences, spectators, spectatorship and such phenomena have attracted a plethora of thinkers and artists to comment on them. I have referred here to those, which I have experienced as relevant to my research arrangements.

The production of audiences

The audience became a part of the performance. We were all like one. (An audience testimonial 5.11.2018, from Draft 8)

Audiences appear in the context of art typically as plural and temporary entities, attending artworks and events without being included in the category of authors of that specific work. So in general, the concept of the audience is based on a binary, or dualistic, model, in which the people engaged with a specific work of art are categorized into those who make the work happen and those who receive it. This dualism is intertwined with and enabled by the status of art as an institution in the contemporary Euro-American context. It has also sprouted a rich discourse with theoretical propositions, emotionally loaded opinions, political claims and experimental artworks that highlight the historical nature of the phenomenon. Personally I have found myself both attacking and defending this binary structure in different phases of my career. In the light of my research it appears (in the current paradigm of art) to be a necessary precondition for the phenomenon of the audience, as well as the key material of the artistic genre of esitystaide (which is dealt in more detail in Chapter 2.3).

The separation of an audience from the makers of an artwork is trivial knowledge to anyone who has attended artistic events, exhibitions, concerts and such. Audiences are produced in multiple ways, usually in combination, for example economically (audiences purchase or receive tickets), temporally (audiences witness the work after it has been finished or sufficiently prepared), spatially (audience is guided to an area that is reserved for them), rhetorically (they are called an audience) and so on. When the ways of producing an audience are repeated for a long enough time, they become trivial, often tacit knowledge.

While a binary structure (in which people are divided into makers and receivers) can in this way be postulated and could be defended with strong empirical evidence, the amplitude with which an audience contributes to an art work is a continuum with infinite gradients and varieties. Performative agencies and resonant potentialities are distributed in different kinds of portions in different artworks and events. In my proposition concerning the formation of an audience body, I have dealt with this through the precondition of subordination and the variable of complicity. In the context of art, the making of it procedurally predates the emergence of an audience: an artistic performance invites an audience to appear. The maker1 is the one who instigates, the audience are the ones who gather as a result. These binary dynamics are a persistent substructure of artworks, even if experimental artists attempt to overthrow any substructure they can find. However, art produces a variety of audiences and audiences submit to a variety of ways of being an audience, sometimes even within the same event. An audience may be more or less complicit in the emergence of an art work and in contrast more or less independent from its emergence. The makers of art use different tactics of differentiating audiences from themselves as well as different tactics of blurring the boundary between themselves and audiences.

Art that differs from the historical and local conventions in terms of the guidelines it gives to its audiences, stands out. Typically art which invites its audience to adopt a more active role than is conventional is considered participatory. All art requires that audiences take part, but conventional participation is rarely called participation. For example, when entering a black box theatre as in my second examined artistic part Audience Body, the convention (even at a festival which programs experimental works) is that the audience sits and watches performers who act on stage. In Audience Body performers are missing and the audience is expected to move on stage, take different objects in their hands and read them in the order and pace of their choice. This kind of work would most probably be labelled participatory. On the other hand, if I would publish the same materials as literature, it would be conventional that the reader chooses what they read and when. Whether something specific is considered participatory or not, is heavily context-related. In the 16-1700s Paris and London theatre artists could rely on their audiences to disturb the performance by commenting aloud, while in the current context of theatre, the theatre makers need to develop imaginative artistic strategies to make their audiences behave in such an unconventional way.

Thus, in the current (Western) art world, an audience is produced as an attendee category separate from the makers in ways that are determined by context-related conventions. These conventions are followed by the majority of the makers and stretched by a minority of the makers by using participatory and experimental practices, which rarely however threaten the underlying binary structure. They sculpt the nature of the convention, not its existence. This provokes a question: is this structure, supported by the current art institution, necessary, and more importantly, still up-to-date? Will our definitions of art become more malleable in the near future as structures of our societies are challenged by the environmental crisis and technological revolutions such as the (so called) artificial intelligence? Is there a post-binary? I will come back to this question in Chapter 3.2.

Philosopher Michel Foucault introduced the idea of an author function. In his proposal, an author cannot be defined as a real individual, but as a function defined as series of operations that are linked to an institutional system of discourses (Foucault 2000, 216). Foucault, addressing mainly the context of literature, writes that the author’s name characterizes a certain mode of being in the discourse; furthermore a discourse with an author’s name “must be received in a certain mode --- A private letter may well have a signer—it does not have an author; a contract may well have a guarantor—it does not have an author. An anonymous text posted on a wall probably has an editor—but not an author” (op. cit. 211). Foucault’s idea has been inspiring to me and seems to apply well to current field of art and performing arts specifically. The practice of using collective names has been common in the esitystaide scene of the Helsinki-area. It can be interpreted as a challenge to the individualistic culture of idolizing prodigies, but it does not challenge Foucault's author function. Authors may hide their faces like the masked Finnish esitystaide-group Teatterinturvajoukot (Eng. Theatre Protection Forces) from early 2000s (see Rosvot December 2005), but they too had a name. Even the pop star Prince, when changing his name to a symbol which is not included in any alphabet, or the ominously named Internet activist network Anonymous—even they have names. Foucault states that “since literary anonymity is not tolerable, we can accept it only in the guise of an enigma” (op. cit. 213). The importance of a name is coupled with the absence of the writer, in Foucault’s interpretation the writer of the modern age “must assume the role of the dead man in the game of writing”. Foucault also proposes that while authors are traditionally seen as genial creators (who are so different from others that when they speak, meaning proliferates), the author function actually produces the opposite: a reduction and limitation of meanings. Authors can thus in this framing be defined as disembodied entities whose names serve through complex procedures as signs that reduce the wealth of meanings into a controllable form.

Following Foucault, the production of authorship requires a certain mode of reception. This mode can be seen as resulting into a production of a readership, or in a broader sense, an audience. An audience could be in effect defined (at least in the contemporary condition) as those people who are involved with the work, but would not in any case be named as the authors, or in a broader sense, the makers. Hence my simplified statement: the audience are the ones who are not named. In addition, audiences function as resonators of the performative actions instigated by the authors. If the named author is a reduction that helps us with our fear of proliferation of meaning, the unnamed audience is where meanings proliferate, but our fear of disembodiment is alleviated.

On the plurality of an audience

It is a really funny word, audience, since it’s like a singular, although it’s like a plural. (audience feedback 16.2.2018, from Draft 2)

The above comment from a participant of one of my experiments hits a crucial point. Linguistics reflect embodied experience beautifully: the audience is a singular that presupposes a plurality. Audience is a condition in which we can simultaneously

1) experience an artwork as an individual person,

2) experience it together as multiple individuals and

3) experience it as a collective entity.

Grammatically, audience can be seen as an entity extending from the category of mass nouns to count nouns. Mass nouns occur typically only in the singular, while count nouns occur both in singular and plural (encyclopedia.com, accessed 27 November 2023). Audience, in most cases, is a singular noun, but we can also speak of audiences, when for example referring to different demographical groups that attend cultural events. Another relevant grammatical observation is the difference between a plurality and a collective. A plurality is the sum of its members, who are concrete individuals with a spatial and temporal location. If a plurality acquires or loses a member, it becomes a different plurality. A collective may be more than the sum of its members and is not identified simply by them, for it can remain the same, even if its membership changes (ibid.). The way the term audience is used does not self-evidently fall into either of these categories. If a theatre play is staged one specific evening and an audience attends, they are the audience of that performance regardless of their identities. This would suggest that the audience is a collective. A participant of one of my experiments wrote:

If you think about it from the performer’s perspective, they always talk about “the audience”. Like “the audience laughed”. Not like “two spectators laughed” or “seven spectators laughed”, but “the audience laughed”. The reaction of the audience is always one. “Tonight the audience liked me”. “What a tough audience”. (audience feedback 16.2.2018)

But for the purposes of an event, each specific individual taking part in the audience has an effect to how the event will take shape. Which would suggest a plurality.

The plurality or collectivity of an audience is an observation and a linguistic fact, but its thematization is also a choice with political implications. The term spectator produces an individual figure with individual experiences and agencies. An audience by comparison does have members, but they are always subordinate to the plural, collective phenomenon. Plurality carries with it relations, connections, contradictions and contaminations, whereas a spectator in comparison can remain intact. Terms that emphasize audience members as individuals are popular both in art discourse and research talk: spectator, reader, visitor etc. Before my doctoral research I also used the words spectator, participant and spectator-experiencer, the Finnish equivalent of which (katsoja-kokija) I coined in collaboration with my colleague Julius Elo in the 00s in lack of a better term. During early phases of this research I decided to direct my attention towards plurality and collectivity and individualized terminology seemed redundant.

Reading sociologist Richard Sennett and art historian Dorothea von Hantelmann offers a historical frame of reference. Von Hantelmann differentiates two ritualized forms of gathering, which enact an underlying social order. The modality of “appointments”, represented by the theatre, has developed when people lived in relatively small communities and a significant amount of the community were able to gather into the same place and time and form collective bodies. The modality of “opening hours”, represented by the museum, popularized in modern, liberal societies, where cities grew too large to be actual communities. Communities were replaced by the imagined communalism of nation states. Liberal individualism was enacted as “individualized gatherings” taking place in exhibitions. (von Hantelmann 2019, 253-54) Von Hantelmann would then regard the transition from a premodern society to the modern one as a transition from my point 3—experiencing an artwork as a collective—to point 1—experiencing it as an individual.

Sennett in turn suggests that “audience” was born through modernity, as the first metropolitan cities like London and Paris enabled gatherings of strangers who would attend the same theatre show. In Sennett’s reading, the 1900s and the subsequent individualisation of culture created the spectator, a solitary figure that replaced the collective entity, audience. So Sennett sharpens von Hantelmann’s distinction and places collective experience (point 3) to premodernity, experiencing something with others (in his terms, audiences) to early modernity in the 1800s and individual experiences (i.e. spectators) to late modernity in the 1900s. (Sennett 1977, 47-24; 205-18)

If we follow this line of thought suggesting that theatres address collective audiences and exhibitions address individual spectators, there are also genres of art that have explicitly dealt with the space in between, such as the genres of immersive theatre and game-oriented performance. For example Upotapia by the Center of Everything or Love Simulation Eve by Avatar’s Journey and Espoo City Theatre represent this approach to the plurality of audiences. Upotapia, categorized by the makers as an immersive and a game performance, took place in a large round industrial space. The makers of the work gave their audience members different tasks aimed at solving an enigma through a collective effort. The tasks created different groupings, dynamics and collaborations during the performance, invoking an active audience body with multiple fluid agencies (Upotapia 16.9.2023). In Love Simulation Eve, the theatre space was divided with fabric walls into cubicles and each audience member was guided into one of them, making them aware of the other audience members through architectural means having their experience parallel, but in private. Inside the cubicles audience members entered virtual worlds created with VR-technology and where they could slightly communicate with their neighbouring members (Love Simulation Eve 14.3.2023). These kinds of strategies often produce, reveal or at best even problematize tensions between the individual and the collective, encouraging audience members to find ways to collaborate or compete—making relational dynamics an elemental area of artistic creation in these genres. While von Hantelmann points out the link between modern liberality and the exhibition format, Adam Alston and Jen Harvie have elaborated on the alignments of immersive performances with the production of the consumer by capitalist market economy (Alston 2016, Harvie 2013).

My research addresses the way collective audience bodies are produced through an asymmetric stage-audience polarity in theatre, and how this setting has been taken as a primary material of artistic creation in the local performing arts, resulting in the emergence of the genre of esitystaide. Similarly to game-oriented performances and immersive theatre, this focus on the stage-audience polarity has led to different variations regarding the plurality of audiences.

Then there is “yleisö”, when in English it is “public” and in some other languages it is “public” and it is funny since it means “julkinen”. (audience feedback 16.2.2018)

Audience corresponds to the Finnish word yleisö, coined by the pedagogue, activist and the founder of the first Finnish-language secondary school Volmari Kilpinen (known also as Wolmar Schildt) in the 19th century. It does not refer to the audible, instead the original meaning is people in general, and the word is literally thus closer to the English word public but is not used in the same way. Instead of people in general, it refers to a group of people who witness or receive the same thing, the most simple example being people who gather to attend a theatre performance. So, in its usage, yleisö equals fairly well with the term audience. Kilpinen is also responsible for several other widely used Finnish words like taide (art), tiede (science), henkilö (a person), esine (an object), ympyrä (a circle) and suhde (relation). (Kuusi 1962, 207, 220)

This audience was produced as univocal. This is the strategy for the publics to appear, that people give feedback and you put it into one word and it is represented as the public talking. (audience feedback 16.2.2018)

The notions of the public, a public or publics are not elaborated in this research, but it is useful to at least mention them, especially due to my usage of the Finnish term yleisö. As an adjective, public points towards accessibility to all or to the whole community, in contrast to something private or esoteric. For instance this research is public in this sense—as have also most of my research experiments been. This meaning of public is to an extent present also in audiences: for example performing to family members can induce the term audience, but it is more of an exception than a rule. The nouns the public, as in the people that belong for example to a community or a nation state, and publics, as in different demographical groups, are not thematized in this study, since in my evaluation they would not contribute significantly to my perspective but would open a large spectrum of problematics and reference materials. However, the above sarcastic quote shows that to address a group of people as one in the current occidental culture is a sensitive and potentially violent gesture. Speaking of audience as a body does this, and furthermore, it does it with the sidenote of questioning the borders of individual bodies. Questioning individual self-determination challenges both the basic principles of consumerism and the politics of diversity. I have felt this gesture necessary to address the phenomena I have studied and I claim that these problematics are not merely a consequence of my questions but also part of the charged nature of the performing arts and the way they compose audiences. While all genres of art attract plural audiences, those that are typical for performing arts are characterized by bodily proximity and contemporaneity. When an audience gathers from different parts of the city into a theatre to experience a performance, with all their smells, sounds and quirks, and take the same position on their seats, it feels unproblematic to say that a collective body has formed. So these kinds of artworks evoke a more collective body than some others. These bodies are local and temporary, plural yet to an extent uniform. These bodies have renounced some of their agencies. They have to an extent accepted being treated as a collective body. A body, which is primarily not performative, but resonant.

Audience as a resonant body

There is a rich discourse regarding the modalities of audience presence in the arts. While artists have developed their idiosyncratic ways to regard or disregard the inevitable presence of an audience, scholars have proposed a variety of possible interpretations of the phenomenon. It has been theorized for example in terms of experience (Dewey 2010), contemplation (Hagman 2011), autopoiesis (Fischer-Lichte 2008), invitation (White 2013), phenomenology (Iser 1972, Wesseling 2017, Mäcklin 2018), performer’s imagination (Bredenberg 2017), feminism (Dolan 2012), synaesthesia (Machon 2011), virtuality (Kirkkopelto 2025), capitalism and neoliberalism (Sennett 1977, Harvie 2013, Alston 2016), relationality (Bourriaud 1998), ritual (Schechner 2016, von Hantelmann 2019), affect (Pais 2016) and listening (Shah 2021, Tiekso 2024). Often also the term reception is used as a general denominator and the field of reception studies has been developed especially related to literature and visual arts.

My proposal to this discourse is the audience body. The audience, in addition to being singular and plural at the same time, is also connected to listening2. As Pia Palme, an audience member of one of my experiments, articulated it:

“[...] the word audience, it comes from listening. A spectator is somebody who looks, the audience is the listener. I can hear what happens behind these walls and I can not see it. The entire idea of a perspective can be abolished from the position of hearing because you can hear everything. [...] Listening is very often experienced as penetrating, also like noise, especially unpleasant things—this would never happen if I looked at something. I can always close my eyes or turn the other way. [...] Every single person in the room influences the acoustic.” (Kucia et al. 5.4.2022)

Palme’s words reflect the nature of sound as vibration travelling in a transmission medium, such as air, water or organic tissue. Bodies are collections of matter composed of substances that function as transmission media for acoustic waves—they carry these vibrations and are penetrated by them. When bodies start to vibrate symphathetically with specific sound waves, that sound is intensified. This is resonance.

The term reception implies a message, which is sent in one location, travels through a transmissive medium and is received in another location. When replaced with resonance, the structure is transformed: the medium merges with the recipient and is moved by the message. In my terms: an audience body is complicit in the medium and is made resonate by the performative act.

Sound and listening function here as metaphors offered by the etymology of the term audience. An audience body does resonate acoustically, but it is affected and transformed also in many other ways, which, like acoustic resonance, engage their bodies in a system where energy is circulated and intensified. For example scholar Ana Pais has proposed affective resonance as the function of the audience: “---the audience has a vital function in performance: one of affective resonance that consists of an intensification and amplification of the circulation of affect. Performers feel and listen to such intensification as patterns of rhythm and felt intensities, with a whole-body listening—that is, through the felt experience of the encounter with the audience” (Pais 2016, 79). Artist-researcher and philosopher Esa Kirkkopelto positions the performing body as the mediator between a source of vibration and a resonant space. The “spectator-listener’s” body registers and shares this event with the performer (Kirkkopelto 2020, 201; 2025, 124). Within this study I will not go further into analyzing the varieties of resonance taking place in an audience body. For the purposes of my argument the metaphoric use of the term resonance is sufficient and appropriate. Resonance implies a state of heightened attunement, where for example affect, emotion, and attention form a collective body, though without the intent to act as one. The audience is a resonant body complicit to the emergence of an artwork.

John Dewey describes how an artist, when working with an artwork, sometimes steps back from the action of making (in my terms the performance), to expose themselves to the work to experience it as if as a spectator (Dewey 2010, 62-73)3. Taking this position, separated spatially and temporally from the position of performing the act of painting, is an attempt on behalf of the artist to prototype the resonances created by the work. Stepping again close to the painting and continuing painting it would return the painter to the territory of the performative. Alternatively, the responsibility for prototyping resonance can be assigned to a specific person(s) in a collective of artists, as is common in currently conventional theatre practices via the roles of the theatre director and the dramaturg. In rehearsals, the director often sits in the auditorium, tuning into and commenting the way the performance makes them feel and directing the actions of the actors based on that. The site of resonance, towards which the artistic practices of prototyping project, is the audience.

Unlike a performance, the quality of which is to make things, to explicitly take space and to change the world, resonance stays relatively unnoticed. While the existence of an audience is also partly performative and—as I will elaborate further later—audiences are complicit in the emergence of art works, their attention is not primarily directed towards themselves as an audience. Audience membership easily escapes attention, by contrast its own position is attentive. Audience does not equal resonance, but an audience is its primary carrier in the context of art. In this research, I am both interested in and actively producing events in which the attention of the audience is turned back towards themselves.

Sometimes resonance surfaces performatively in a performance; in specific moments it can be almost palpable. For example, in Nano Steps by the group Trial & Theatre the performers manipulate miniscule particles with sound, while projecting an enlarged microscopic view of the particles on a screen at the back of the stage. We, meaning the 300 audience members of the show, sit silently in the auditorium while performer En Ping Yu is making small sounds with different materials and uses a microphone to amplify them for the purposes of this particle puppetry. In one moment of silence, an audience member coughs. The particles jump on the screen. The audience notices how this involuntary sound that has emerged from us has affected the sensitive technological arrangement onstage. We laugh. Particles jump again in response. The silent resonance that has lurked there all along unnoticed and its effects on the performance become suddenly obvious. While I was just before witnessing the events onstage as if from an untouchable distance, I am now flushed by the sensation of sharing the same air with the stage, with everybody, and the same vibrations of that air hit all of our eardrums in the same instance as if we were only one body. (Nano Steps 8.8.2023) Or to place in parallel Sara Grotenfelt’s Last Hurrah, in which we, the audience, receive party hats and snake whistles as we enter the space and an instruction to blow the whistle whenever we see something we like. Normally it can be almost impossible to know what the other people are feeling. It is for the most part beyond perception or at least on unconscious perceptive levels. This hidden experiential realm is now magically heard, made into a playful soundscape and an odd feedback loop between Grotenfelt’s body and that of ours. (Last Hurrah 8.8.2022)

Or when performer Jenni-Elina Bagh self-consciously says onstage in A Prologue: “A performer has to be real and an illusion at the same time”. The sentence keeps reappearing in my thoughts and I start noticing how my mind works, partly following the happenings onstage and partly creating its own dramaturgy, with wild associations and seemingly irrelevant sidetracks, as if performing the Foucauldian proliferation of meanings. I realize: an audience member has to be awake and dreaming at the same time. (A Prologue 1.10.2022) In all these cases we as an audience resonate while the tacit qualities of this resonance appear before us as these revelatory experiences—sometimes to all of us, sometimes to some of us, sometimes to just one of us. Or one could say as well: sometimes to the whole collective body, sometimes to parts of it, sometimes just to one of its members.

When viewed from the perspective of artistic practice, the resonant nature of audience bodies can be approached through the act of tuning. The art of acting in contemporary times, a research project realized in 2008-10, defined tuning as one of the basic ingredients of the technique of acting they developed: “Tuning is a psychophysical movement or a series of movements, with which psychophysical resources are mobilized and perceptive fields are opened” (Hulkko et al. 2011, 211, my translation). In the context of my research, tuning can be defined as a way the makers calibrate the resonant transmission medium, which includes the audience body, appropriately for the specific art event at hand. Tuning is a way for the artists to prepare the audience body to function like a musical instrument. This skill is referred to by my informants in Chapter 4, Audience Body, Work-in-Progress 2. A more detailed articulation regarding the techniques of tuning audience bodies falls beyond the scope of this project, while it is arguably present throughout the practice disclosed in Chapter 4. Conversely, one could say that audiences also engage in acts of tuning their own selves to resonate with the works they encounter.

Some brief histories of audience bodies

Different media and the related genre-specific traditions have over time resulted in several parallel conventions regarding the ways audience bodies are summoned4 to resonate with artistic performances. Concurrently also the role and the tasks of the audience have been organized. While following these historically produced conventions is important for artist pedagogy and audience outreach, disturbing them produces an experimental status for the way audience bodies form and is therefore useful for artistic research. This kind of intermedial experimentality has been a key element of my own research practice. Below I will describe the way I have conceived the historical developments and scholarly contributions that are relevant and informative for my research practice.

The etymological roots of theatre are located in the sphere of spectatorship, sensory reception and spatiality, as the Greek word theatron originally meant a “place for viewing” (Online Etymological Dictionary, Accessed 7 May 2024). I emphasize the word place, since the etymology of theatre anticipates how spatiality has particularly been utilized for creating resonant audience bodies in the context of theatre. Ancient Greece and especially the city state of Athens is generally considered the birth place of the Euro-American theatre tradition. Philosopher and theatre maker Denis Guénoun addresses the way theatres were built in Ancient Greece as semicircles, in which the audience could see not only the events on stage but also each other (Guénoun, 2007, 17). The etymology of theatre along with the architectural innovation of the amphitheatre (etymologically “spectators all around”) serve as evidence to suggest that spectatorship was an integral part of the practice of theatre already two and half millennia ago. This argument can be extended to propose that the auditorium was an instrument designed to enable resonance in a collective audience body. In addition, Aristotle introduces the emotional impact of a poetic work to its recipient as its goal (Heinonen et al. 2012, 12). Along with other public activities, spectatorship was considered an integral part of citizenship (which was limited to free men). While there is a danger of anachronism, the way resonance seems to have been included in the theatrical event in Athens around 500-400 BC is not very far from the phenomenon of esitystaide I describe in this thesis.

Later on, in an encyclopedia entry Parterre (Eng. Theatre pit) from 1776, Jean-François Marmontel writes about the class-related structure of French theatre architecture of his time and its consequences on the experience of the spectator (Marmontel, 2003): the cheaper the ticket, the less comfortable the audience experience. The theatre of Marmontel’s time, similarly to the Globe Theatre in London in early 1600s, was a version of the amphitheatre, in which the wealthy elite would sit in the rows of seating encircling the round floor, or the pit, upon which the working class audience would stand (the British society and the status of theatre in it has changed, but the ticket system has been revived in the re-built Globe Theatre. I visited the Globe a couple of times during the research process, see for example Othello 29.8.2018). Marmontel introduces internal differentiations and tensions as a feature of audience bodies.

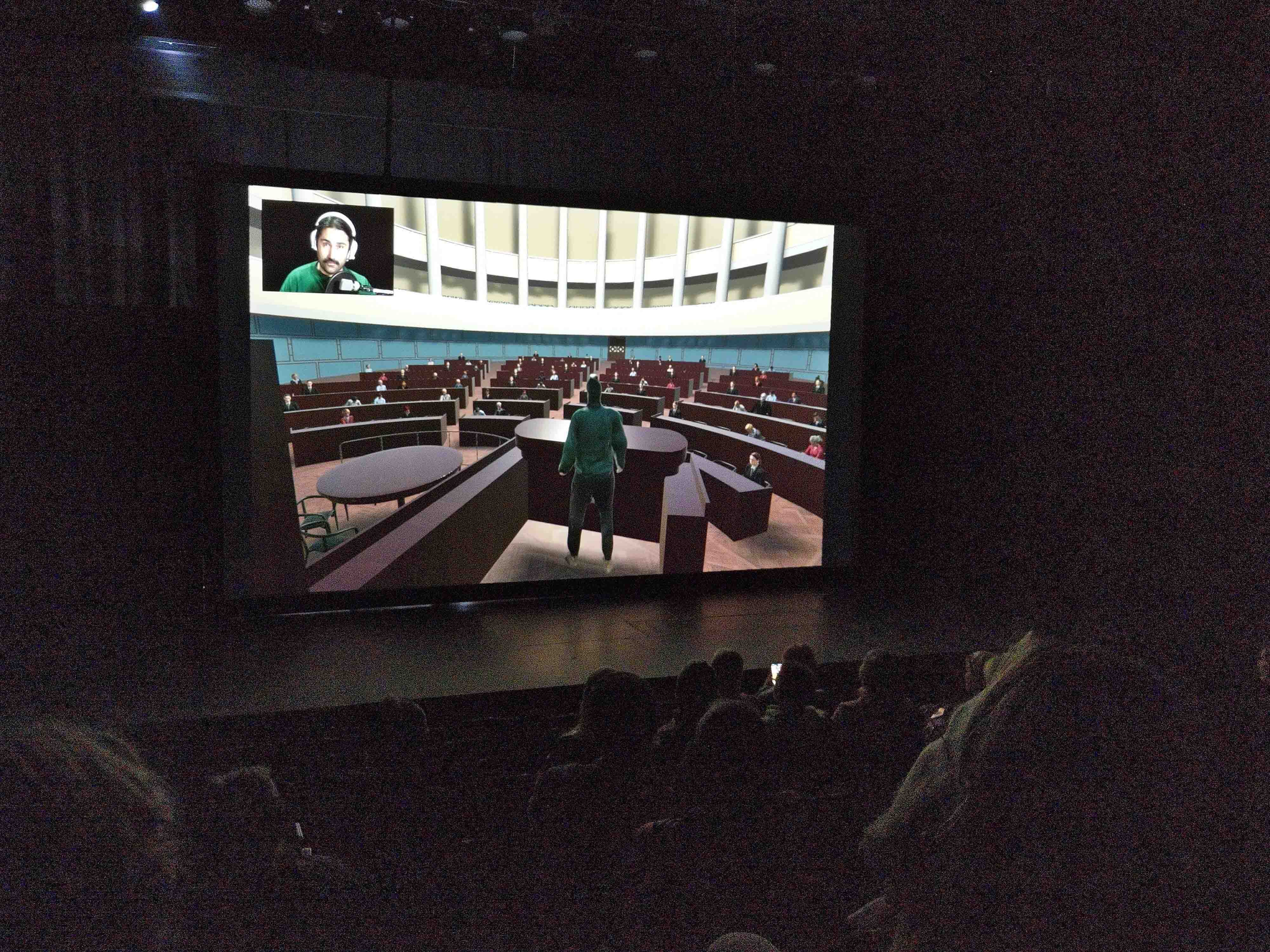

Moving on towards the next century, Erika Fischer-Lichte explains how theatre makers of the late 1700s started to experience the active participation of audiences (it was normal for example to comment the play aloud or argue in the auditorium) problematic and several changes were made regarding the position of the audience: prohibitions and sanctions were installed, the audience was left in the dark as gas lights became available and auditoriums were built in a way which made exiting the room more difficult (Fischer-Lichte, 2008, 38-39). The composition, familiar to theatre audiences of our time, was normalized: actors perform on a lit stage while the audience sits silent in rows of seats in an unlit auditorium. This change seems radical: openly active and complicit audience bodies were silenced and their resonant nature was hidden from sight. The polarity and the contrast between the performative and the resonant part of an artistic event was emphasized. In the light of the performances attended by me during this study, the conventions regarding seating and lighting have changed from 1800s to the contemporary experimental performance scene, but the requirement of silence from an audience is still a strongly defended norm even there. Exceptions do exist: for example Harold Hejazi’s Adventures of Harriharri -series superimposes the format of a multiplayer online game with the stage-auditorium-setting of a theatre. Hejazi performs via a projection of a virtual environment, where his avatar Harriharri operates. While playing Harriharri, Hejazi asks for help from the audience and encourages them to shout what he should do next (Adventures of Harriharri—episode 3 19.5.2022).

If theatre artists have emphasized spatial differentiation of the acts of making art from resonant audience bodies, in the genres of literature and visual arts temporal differentiation has been emphasized. The novel and the painting have been finalized before the audience encounters them. The finished artwork, either a unique object or a material copy of linguistic and typographical content, has been the container of art reaching across time from its making to its resonances. In a theatre audiences are limited to a specific part of the building and it is thus easily traceable where the resonant function is situated, while in a gallery or library the finished object serves as the primary proof of the fact that the making of it no longer takes place and the question is when resonance takes place. Literature sprouted from an oral tradition of telling stories and its origins are thus intertwined with those of the performing arts. The development of printing techniques enabled private reading experiences to become more and more accessible as centuries passed. Umberto Eco traces how the responsibility of the reader has increased in the history of literature: in the Middle Ages writers like Dante were conscious of the multiple possible interpretations of a text but limited those possibilities to few; in Baroque the reader was for the first time faced with a world in a fluid state requiring their own creativity; modern writers such as James Joyce purposefully left their works open for an unlimited number of interpretations and modes of resonance (Eco 1989, 5-11). Eco’s formulation echoes Sennett’s and von Hantelmann’s analyses of the time of individual liberalism with regard to art audiences.

The early 1900s brought new flavours to the resonant spectrum and several theorists have claimed a “birth of the spectator” (Wesseling 2017, e.g. 172-3) or a turn of some sort—some date it around the turn of the century, some in the 1950s-60s. Technology, politics and aesthetics all went through massive processes throughout the century. As mentioned, Sennett placed the birth of the solitary figure of the spectator in the end of 1800s (Sennett 1977, 205-218), art theorist Claire Bishop introduced the idea that historical moments, in which collectivity is in crisis in society, give rise to an avalanche of participatory art: in the European context especially the events in 1917, 1968 and 1989 (Bishop 2012, 3)—so in a way Bishop suggests three births or turns regarding the ways audience bodies were summoned. As recording techniques and other kinds of ways to mechanically reproduce art became possible also in other genres than literature, audience bodies were more scattered across the geographical terrain. Audio record players, photography, movie theatres, radio and TV broadcasts created new kinds of scattered formations. (see e.g. Benjamin 2008)

Simultaneously, the first Avant-garde movements challenged the normalized position of audiences as well as the popular functions of art. Suprematist, constructivist and ready-made works such as Kasimir Malevich’s Black Square and Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain, both from the year 1917 proposed by Bishop as a crucial point, introduced new kinds of spectatorship of visual arts via disorienting the ways a work should be encountered and anticipated the coming of minimalism after the Second World War. In the context of theatre, the role of the director was instituted, as a kind of a proto-audience-member, which increased the importance of the communication between the stage and the auditorium in theatre practices (Fischer-Lichte, 2008, 39). The way stage performances and audience bodies affected each other started to be used more consciously as an area of artistic creation. Dewey introduced the experiential paradigm in 1932 in the seminal book Art as Experience (Dewey 2010).

In 1950s and 60s a new wave of artistic styles and genres questioned the former ways of organizing audience bodies: minimalism, installation, happening and performance art demanded more from their audiences. This was noticed by scholars as well and there were several theoretical proposals regarding the transfer of agency from makers to audiences—new births of the spectator. In literature, along with semiotician Eco, literary scholar Roland Barthes (Barthes 1993) and German reception theorists like Hans Robert Jauss and Wolfgang Iser (Holub 1984; Iser 1972) emphasized the agency of the reader at the expense of that of the writer. Barthes announced the death of the author, Iser coined the concept of an implied reader. He suggested that a text always implies a type of reader and this reader typically resembles the writer. Michael Fried framed in his seminal 1967 article Art and Objecthood the inclusion of the spectator in minimalist artworks as theatre. In his view, theatre exists for an audience in a way other arts do not. Fried articulated an interesting claim: that the spectator is a part of theatre events (or in his terms situations), but not a part of art objects produced in the field of visual arts. The inclusion of the spectator in the art work meant for Fried that the work changed into theatre. (Fried 1998) Continuing from Fried’s argument, in my proposal audience bodies are organized with regard to the intensity of the contact between the performative and the resonant. In visual arts the contact is typically mediated by an object and as a result mitigated, while theatre is an art of more intense contacts5. In the context of esitystaide artworks invite audience bodies into even more intense contacts with the makers and each other through using the contact itself as a material.

The same year Fried released his article, the central figure of the Situationist International (like Fried, using the term situation, but in a more positive sense), Guy Debord, published his also seminal book La société du spectacle, advocating an active citizenship and creation of situations instead of passive spectatorship, into which capitalist society drove people in his opinion. Looking back from the age of the Internet and social media, Debord was prophetic in his diagnosis. Esitystaide could be to some extent seen as realizing Debords political ambition and a situational art form par excellence, the shortcoming being the fact that it resides as a marginal phenomenon within the institution of art (instead of emancipating masses). Later on, Dorothea von Hantelmann has proposed that an experiential turn has taken place since 1960s both in societies at large due to the change from lack to affluence and specifically in the arts (von Hantelmann 2014).

In the 70s, Richard Schechner developed the term environmental performance, referring to performances in which the stage was spatially situated all around the spectators instead of a designated stage area, diluting the protective layer around audience bodies and anticipating the genre of immersive theatre of the 2000s. In the 1980s Hans Belting and Wolfgang Kemp continued the work of Jauss and Iser by examining the possibilites of reception aesthetics in the realm of visual arts (Wesseling 2017, 50). Marco de Marinis introduced in 1987 the idea of a dramaturgy of the spectator as a part of the work of theatre artists (de Marinis 1987). In the 90’s context of visual arts, Nicolas Bourriaud coined the term relational aesthetics to account for works, which moulded social space like a sculptor would mould clay, suggesting that a new era of socially engaged art was dawning (Bourriaud 1998). If Bourriaud praised relational works for their topical relevance, Claire Bishop’s already mentioned analysis of participatory art took a more critical view on the abundance of acclaimed participatory artworks of the 90s and the 2000s. Bishop highlighted the fact that participatory works were applauded for their social value, while a critical view on their aesthetic quality was neglected. (Bishop 2012, 26-27) The complicity of audience bodies was not merely an issue of political power or social equality, but a multifaceted and complex area of artistic creation.

While experimental literature had been there to challenge the normalized positioning of the reader, that position became more acutely a subject of explicit concern through the proliferation of electronic literature. A normalized reader interface such as the book does not exist in the electronic sphere and the creation of the interface is thus considered part of the work itself. Researcher Espen Aarseth has introduced the concept ergodic literature to cover those forms of literature in which the way of reading is not trivial (Aarseth, 1997). Aarseth’s concept has been informative for my research, and especially through his brilliant wording “not trivial”—participatory performances can similarly be defined as those performances in which the position of the audience is not trivial.

In 2009 philosopher Jacques Rancière published an influential text The Emancipated Spectator, in which he criticized the attempt of the reformers of theatre practices to activate spectators. His claim was that spectating a performance is always an active process and that it is an arrogant and misguided aspiration to try to liberate spectators from an assumed passivity and evoke them to actively take part in politics. Rancière claims that spectators are already active and able and should not be considered subordinate in relation to the makers. (Rancière 2009, 11-15) My experience is that experimental theatre makers do not necessarily consider spectators passive and that Rancière makes unwarranted generalisations regarding artists and their work to validate his claims (Gareth White elaborates on this in White 2013, 20-24). However, Rancière’s text opens a space for arguments such as my proposals of resonant audience bodies and parapractice. To expand on his notion, I suggest that this resonant component of art is a polar opposite of agency, taking place anywhere within the aura of an artistic work, while residing permanently and contently within audience bodies. Therefore, while an audience body has agencies and while it does influence the active processes taking place in the work, it is in my definition not performative nor active but resonant by default. Following Rancière, this is not a value judgement—non-active does not equal not good.

2 The English word audience, as it is related to the sense of hearing or more specifically to “the act or state of hearing, action or condition of listening”. The Proto-Indo-European root au-, to which also the word aesthetic is traced, means “to perceive” (Online Etymological Dictionary, Accessed 6 May 2024).

4 The term summon from an interview with an audience member of A Reading of Audience, Olga Spyropoulou (Spyropoulou 21.12.2020, A Reading of Audience video)

5 The artist Teemu Mäki has suggested that radical proposals are more common in fine arts and poetry than in performing arts, due to the fact that performing artists are more at the mercy of their audiences (Mäki 2011).