In the practice room

1. Introduction

“Everything can be achieved by practice”.

(Periandros - tyrant of Corinth, died 587 BC).

But what does the word practice mean? There are as many ways to practise as there are possibilities to improvise a three-minute piece of music. Is practicing repeating things a hundred times, slowing things down, chopping things into small pieces, making analyses, imagining movements. Is it mental training, listening to a recording, playing lots of variations on one passage? Trying to find one specific color, singing, humming, experimenting with tempi, exaggerating dynamics, exercising how to breath well…. Is looking out of the window and letting the movements of the tree that you see, sink into your consciousness, practicing as well? Listening to the sounds that are in the room before you start playing and letting your imagination dwell? Can day-dreaming or whistling a phrase of your repertoire under the shower and enjoying that, also be called practicing? Taking or creating melodies and transforming them into something else? Pablo Picasso’s famous saying goes: “I do not search, I find”. When exercising ourselves in something creative as making music, we would like to practise – alongside skills and physical routines needed to use the instrument well – how to arrive in a state of mind where we are always a bit more likely to ‘find’ instead of ‘search’.

A full survey of ‘practising’ understandably reaches outside the scope of this research. However, there are two reasons that make a chapter on practising routines in this research report relevant and essential: 1) a major part of the research has ‘happened’ in the practice room and 2) in line with the paragraph above, in my experience we spent - in educating ourselves and our students to become skilled violinists – a lot of practice time and attention on developing repeatable precision, but in comparison much less time and energy on developing creativity, exercising how to arrive in a state of curiosity and readiness to react to whatever happens. As the heart of this research is about improvisation and finding ways to internalise harmony ‘coming from the own creativity’, it is crucial to look for ways how ‘practice’ can happen in that direction.

2. Soft skills and how to develop them

In ‘The Little book of Talent – 52 tips for Improving Skills’, the author Daniel Coyle presents the distinction between ‘hard skills and soft skills’1.

“Hard, high-precision skills are actions that are performed as correctly and consistently as possible, every time. They are skills that have one path to an ideal result; skills that you could imagine being performed by a reliable robot. Hard skills are about repeatable precision, and tend to be found in specialized pursuits, particularly physical ones. Some examples:

-

a golfer swinging a club, a tennis player serving, or any precise, repeating athletic move’

-

a child performing basic math

-

a violinist playing a specific chord

[..]

Soft, high-flexibility skills, on the other hand, are those that have many paths to a good result, not just one. These skills aren’t about doing the same thing perfectly every time, but rather about being agile and interactive; about instantly recognizing patterns as they unfold and making smart, timely choices. Soft skills tend to be found in broader, less-specialized pursuits, especially those that involve communication, such as:

-

a soccer player sensing a weakness in the defense and deciding to attack;

-

a stock trader spotting a hidden opportunity amid a chaotic trading day;

-

a novelist instinctively shaping the twists of a complicated plot;

-

a singer subtly interpreting the music to highlight emotion

[..] “

In the second list, this one could be added: ‘a violinist improvising music and in doing so, raising his awareness of harmony…This distinction is extremely appropriate and vital regarding the present research. It will be clear that improvising music asks for ‘soft skills’ (of course provided enough ‘hard skills’ being there).

The research has shown that essential ingredients in practicing soft skills are:

-

Watching the mind being flexible all the time. When you get stuck in doing the same thing, shift attention to something else2.

-

Thinking in images. Training your mind and imagination in coming up with images, atmospheres, emotions. Starting to play along with them. Building an ‘inner catalogue’ of images, emotions, atmospheres, character, that you can browse

-

Taking moments to pause, to nót play. In those moments, visualizing yourself creating something, that is preparing for the playing to come. In a fascinating workshop with actress Dinah Stabb, she explained the participants – being musicians –how actors ‘practice’ the bit of the play that ‘is not played’ – they exercise themselves in acting something that happened before the scene they are going to perform, or they rehearse by playing something that could happen after the scene they are going to perform is finished. An utterly beneficial thing to do, that can well be translated to practicing music in an improvisatory way.

-

After having played something in a way that you are ‘quite satisfied’ about, trying not to repeat that ‘successful one’ but trying to do it in a few different ways afterwards.

3. The ‘One-note game’ – about warming up and waking up the imagination

One possibility of starting improvisatory practice, can be the following game.

|

Choose one note on your violin that you find attractive, enjoyable to play. Start with this note, listen to it well and sense which notes you would like to play after it. When you have played ‘a little excursion’ come back to this one note. Create a bit of music, where you make excursions like this, always coming back to the one chosen note, this one being the ‘core’ of the piece. |

After you have done this, try to recall roughly what you just played. What did the ‘song’ you just played do to you? What emotion and what energy did it communicate? What ‘tonality’ was it in - if it was ‘freely tonal’ which ‘approximate key’ was it in? If you would you like to play a next ‘one-note piece’ in the same atmosphere and energy, do so. If you want to play a next one of a contrasting character or energy, do so. Play two or three more of those ‘pieces’ - until you feel it is time to do something else.

This game is specifically aiming at not only ‘warming up’ in the sense of fingers moving flexibly, violin technique being awakened, sound of the day being recognized, but it is also aiming at ‘waking up the imagination’ - meaning that one deliberately challenges the mind to come up with different images, to wander and move around, to ‘search’ for contrasting energies.

An elaboration of this ‘one-note game’ is the old tradition of improvising preludes.

|

Variation: with a chosen note ‘in mind’ in a pivoting role, improvise a small prelude. You can think of involving different ‘violin techniques’, rhythms, motives. |

4. Browsing through chords

In this exercise you ‘take a flashlight and go search in your inner, hidden world/knowledge of harmony’. The knowledge that you do possess, because you (might) have played so many great pieces of repertoire that are written in the enormous space of classical harmony – that is all stored somewhere inside you. The idea is that you start using chords and harmonies as ‘building blocks of lego’ and start building-in-a-playful-way with it.

|

Option 1: Choose one chord and play it out. Listen internally what could be ‘a’ next chord to follow and play that one out. Continue like this and try to recall afterwards ‘which route’ you have been taking. Pay attention to how transitions feel, what sensation do they give – do they feel natural, beautiful, sudden, awkward, bumpy or smooth? |

|

Option 2: Same as above, but for the next chord that you play, you only change one note of the previous chord. |

|

Option 3: Choose two different chords. Now find a route from chord 1 to chord 2 that sounds satisfying (For example: is there one chord that creates a natural ‘bridge’ between the two). |

|

Option 4: Search for ways to move through the cycle of fifths in both directions, by creating a suitable ‘bridge chord’. Train yourself in playing them out in an improvisatory way. For example by moving I-V-V-I I-IV-V-I through the cycle of fifths, joining them by the ‘bridge chord’. |

|

Option 5: Choose a diminished chord. Try out – first trying to imagine, then playing on the violin - different possible chords that sound natural following this diminished chord. |

In this option 5 you will recognize how diminished chords act like ‘chameleons’. They can be ‘everybody’s friend’ very easily. Enjoy the different ‘tastes’ that the various friends give to the ‘chameleon’.

Keep in mind what was mentioned in ‘Soft skills’ – when you sense the mind becomes ‘stuck’, or too thinking, or the ‘healthy curiosity and enjoyment’ are gone – move to something else and come back to this another time.

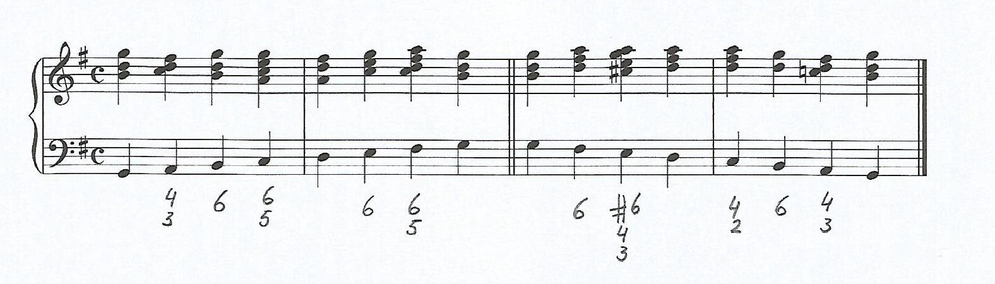

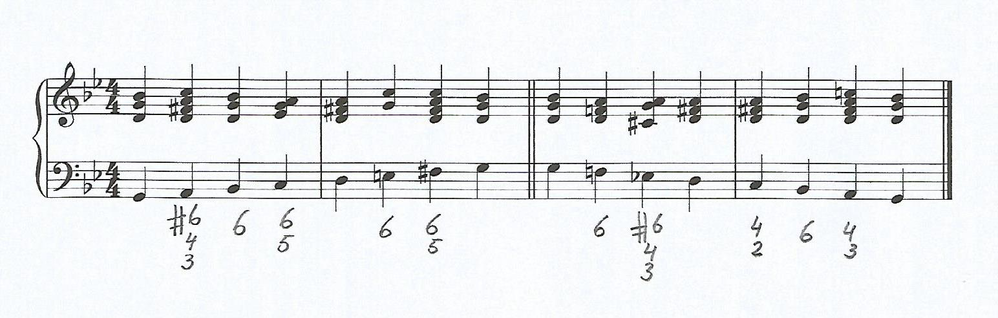

5. The rule of the octave3

|

Option 1: Choose a major scale and play it, one octave up and down. Now play it again, playing out on every tone of the scale a chord that ‘feels natural’. Try this a few times, experimenting with different options. |

A diatonic chord on each tone is in total not giving the impression of a ‘musical phrase’ very much – it feels more like ‘different bunches that do not have to do so much with each other’ (our instinct is rebelling against all the parallel fifths).

Start trying out ‘different options’, try out on which scale degrees in the bass a sixth feels good. You might arrive at ‘liking’ a sixth on all scale degrees, except on I and V.

This exercise leads to what is known as ‘the rule of the octave’. In the book ‘The rules of music – for beginning keyboard players by Vincenzo Mazzola-Vocola’ – written in Naples in 1775 this 'rule of the octave' is explained clearly. In short, it explains how our ‘classical trained ears’ for the music until ca 1870 experience the following chords to sound ‘natural’ on the scale degrees of a bass line moving up and down a scale:

The chord on the sixth scale degree on the way back poses an interesting moment. A diatonic sixth on the bass note here is not sounding 'wrong', but in the rule of the octave as presented to us, this sixth on the bass note is raised half a tone - resulting in what we nowadays call a secondary dominant.

Once you try that out you will probably ‘like it even better’ – it creates a great tension – leading tone – to the note on the fifth degree of the scale.

|

Option 2: play out the ‘rule of the octave in all twelve major keys. |

|

Option 3: Now do the same as in option 1, but in a minor scale. |

After you have gone through the same process with the minor scales, you will probably realize that minor scales offer more different possibilities. On the sixth and the seventh degree, many possibilities sound ‘pleasing to our ears’.The sixth degree on the way back poses an interesting moment again. A diatonic sixth on this sixth degree is not sounding 'wrong', but in the rule of the octave as presented to us here, this sixth degree is raised half a tone.

Once you try that out you will probably ‘like it even better’ – it creates a great tension – leading tone – to the note on the fifth degree.

|

Option 2: play out the ‘rule of the octave in all twelve major keys. |

|

Option 3: Now do the same as in option 1, but in a minor scale. |

After you have gone through the same process with the minor scales, you will probably realize that minor scales offer more different possibilities. On the sixth and the seventh degree, many possibilities sound ‘pleasing to our ears’.

Playing out the rule of the octave in different ways through different keys will make you ‘know’ the fingerboard of your violin in a totally different way!

|

Option 4: Play out the ‘rule of the octave’ in all twelve minor keys. Make variations in register, thematic material, metre. |

In the period of basso coninuo playing, in classical music the bass line used to be the leading voice. A remark with a major impact for melody-players and violinists ‘from now’, as there it is quite a ‘different view’ at the moment – we violinists tend to experience our playing and the score very much from the melody part! When performing repertoire from the above-mentioned period, in order to ‘become empathic’ with the time it was created in, it is therefore important that we can ‘also feel different in this balance’. Playing out exercises from bass lines in the way presented above, can help shifting that balance. Mazzola-Vocola makes the following remark in his dissertation:

“When the partimento descends stepwise, it can accept various accompaniments.”

The partimento being the bass line, the melody being ‘the accompaniment’.

6. Creating figured bass lines.

In the previous chapter, the basic principles of figured bass notation have been explained. To make figured bass reductions of repertoire oneselves has proven a powerful way to internalise harmony and it offers – after a figured bass reduction is made – two things: an analysis of the piece that is very much 'owned' by the player himself (not 'told from the outside) and a practical tool to improvise on and to help playing with the repertoire in a creative way.

Steps for making a figured bass reduction of a piece of repertoire:

- Listen to the music. When listening, focus on following the bass line.

- Try to sing the bass line with the recording and play it on the violin.

- Write down the bass line.

- Listen to the music again, now focusing on the harmonic progression.

- Try to play out chords with the recording (or if you know the piece well enough by ear: without the recording playing).

- Write down the numbers that correspond with the chords you hear.

Once you have created a figured bass reduction of a piece of repertoire, it is a great exercise to play it out in different ways. Doing so creates ‘active awareness’ of the ‘important moments’ in the music. It sheds a light on possible (different) ways of phrasing.

In Appendix I, a selection of (fragments of) repertoire is provided, that can serve as good ‘exercising material’ to make figured bass reductions. Figured bass reductions and some comments are presented as well.

7. Creating melodies

This research is focusing on internalising harmony for violinists. Violinists – being melody-instrument players – from nature tend to be good at inventing melodies! In order to grow in hearing harmony better and in order to become a more skilled (tonal) improviser (which will help you enhance harmonic awareness) it is also beneficial to exercise in ‘creating melodies’.

|

Option 1: Take a melody you love. Sing it and play it a few times by ear on your violin. Now improvise a short phrase that feels very close/similar to it – in sense of character, or rhythm, or movement/stillness. (Think of it as ‘playing the same melody, but with other notes’). |

|

Option 2: Think of a few melodies starting with an upbeat. Realise what the interval of the upbeat is. Improvise a short phrase starting with an upbeat of that interval. For example: play melodies starting with an upbeat of a fourth or melodies starting with an upbeat of a minor sixth (beautiful!) or with an upbeat of an octave (intense!) or with an upbeat of a ninth (even more intense - dramatic!).4 |

|

Option 3: Similar to the ‘one-note-game’ – play melodies that are ‘as flat as possible’. Explore ways to create melodies around one or two notes. Think of melodies that you know that start ‘flat’ like this (For example: theme from Beethoven Symphony nr. 7, 2nd movement, Allegretto’) and observe how composers deal with it. |

|

Option 4: Choose a sentence, think of speaking the words and improvise a melody to it. If you find it difficult to do so, you can start with the rhythm only. Then ‘colour in’ notes/pitches to this rhythm. |

|

Option 5: Choose three notes. Play melodies that are only using those notes. Become aware of how you are using rhythmic variety to build a shape or tension/release in a phrase with such limitations. |

|

Option 6: In the moments you are not practicing (on your bicycle, waiting for the bus, under the shower, when you can not sleep at night, walking through the forest, doing the dishes, cleaning up the house…), create melodies…. In your head, or humming, whistling, singing. |

In line with this last option - a quote from Jeffrey Agrell’s book5

“Shower music [..]

Your daily shower is your chance to sing your heart out and sound terrific. Feel free to sing the oldies, but use the aural enhancement to create new music as well. Sing about the day, about dirt and soap, about the feeling of hot water and being clean. Sing about a broken heart, about new love, about the sun coming up today. Make it raw, real, and raucous. Do it every day!”

8. Play-along recordings

To train yourself in tonal improvisation skills, play-along recordings are an extremely helpful tool. The equipment needed for it is nowadays completely within reach: a computer with good speakers, or an extra speaker to attach to it – and the play-along recordings themselves.

This last item is posing a small problem, as play-along recordings are still scarce when it comes to learning to improvise in a ‘classical music style’ – whether that means ‘baroque’, classical, romantic or ‘modern-tonal’. Youtube offers an amazing amount of play-along recordings: jazz, blues, tango, Latin jazz, funky. Most of the jazz play-along backing tracks come with a picture of the chord scheme. It is already an excellent ear training and a great way to ‘drink in the harmonic basis of the piece’ to listen to the backing track while just imagining, whistling, humming ‘something like an improvisation’ on top of it. Berklee online offers courses that provide many play-along possibilities for jazz musicians. For classical musicians however, there seems to be a niche here.

From the books mentioned in the bibliography, only three come with a play-along CD. The CD with Martin Erhardt’s book is very useful, but the instrumentation steers strongly in the direction of ‘early music style’ playing. The CD’s with the books by Eugene Friesen and Eduard Sarath are in a jazzy style. Pianist Bert Mooiman has made a collection of play-along tracks – 57 one-and-a-half-minute backing tracks of pendula, simple schemes and Schubert Waltzes, called ‘Improvisation minus one’ – that proved to be helpful practice material. The backing tracks are recorded on a harmonium, which results in open possibilities to play in different styles.

An easy solution for less complicated progressions here, is to provide your own backing tracks. A recording device (for example the Zoom H2N) and some basic piano skills will do the job. On the left you find examples of 'home-made backing tracks'. The good thing about self made tracks is that you can provide them in all scales, and that you can vary the tempo and metre. The drawback of self made tracks is that they will only sound as good as the limits of your own piano playing allow.

There are many different things one can do with the same play-along recorded track – and exactly that is one of the great benefits - in order to ‘keep the mind and concentration flexible’ one can vary a lot and thus learn in a more ‘soft skill’ way.

Examples and suggestions to work with play-along recordings:

|

Example 1: Put the track of a T-D track on ‘automatic repeat’ and play along a few times. For every next time that you play, decide that you will create something different, for example:

|

Taking time before a next ‘go’ and in this time, browsing your catalogue of ideas (thinking of images, or ‘listening internally’) and imagining how it would feel to be able to ‘just go and improvise in the imagined way’ is a good thing to do.

Also - listening to the track a few times - without playing - but listening so actively that you ‘listen through’ it - you listen to the track and to ‘what could have sounded with that track’ - is a strong exercise. It is wonderful to experience that you can hear ‘something very different’ every time that you listen to the exact same track.

|

Example 2: Put the track of a progression (for example the Monte sequence) on ‘automatic repeat’. Listen to the track one time or a few times. Try to play (repeat, copy) the chords on your violin without the track running. If you encounter ‘blank spots’, listen again and try again. Play the chords along with the playing track (you can play the chords arco or pizzicato). Play the track a few times and sing along bass line, voice starting on the third, voice starting on the fifth and voice starting on the tonic. Whenever you find it difficult to do – just listen! If you feel your mind becoming too ‘stuck’, sing along ‘something random’ a few times, until you enjoy doing it again. Play along the different voices on your violin. If it proves to be helpful, mention in your head the names of the chords you are playing while playing (D, G, E, A, Fis, b, G, A, D). Only if you really need this, write it down in a simple way. Without the backing track, see how far you have internalized the scheme by transposing it to different keys. Come back to the key of the track and play different melodies, registers, characters, rhythms on the sequence. |

|

Example 3: Put the track of a Schubert Waltz on ‘automatic repeat’. Choose one or several of those options:

|

Playing around with Schubert Waltzes likes this, creates a ‘close encounter’ with the composer. It might make you love Schubert even more than you already did. As pianist David Dolan put it once: “Schubert is the magician of changing the meaning of one note”. Working on the Schubert Waltzes like this makes it possible to experience that from the inside, ‘live it out’ and therefore understanding that in another way.

Similar to what is mentioned above, when working with the play-along recordings, it is important not to do the same thing too long in one go, take care of a lot of variation and watch a ‘curious, enjoying mind’ to remain ‘curious and enjoying’.

9. The art of listening

In practicing we tend to play most of the time, but it has proven how valuable it can be to spend enough time not playing as well. A major part of this ‘not-playing’ time is focusing on training ourselves in ‘enhancing the skill of listening’. It is an open door, but very true that when we are making music, it is much more about the quality of listening than about the quality of playing. How can we train ourselves to become better listeners? What different ways of listening are needed whit regard to improvising music when compared to performing already existing repertoire? A relevant and fascinating question.

Suggestions for efficient strategies here fall into three groups:

1) activities connected with listening to music that is played ‘physically’ (recordings, play-along recordings, students performing repertoire, concerts) in always different, deeper, more imaginative, more active ways.

2) activities connected with listening to music that is not ‘played physically’, meaning: listening internally to what you imagine to sound, or ‘hearing around’ music you know.

3) activities connected to listening to silence. This might sound ‘awkward’ but listening to ‘silence’ is a great way to deepen the quality of listening to sounds. Silence seems to come in ‘as many flavors’ as music sometimes.

A few remarks about these three categories of ‘enhancing-listening’ activities.

1) When listening to music that is being played, you can:

- Train yourself in focusing your attention on following certain voices or parts.

- Ask yourself always different questions when listening. For example: ‘What does the music tell you’ - what does it make you experience? More specific questions as: what moment in this music do you experience to have the most intensity? What part of the music do you particularly enjoy? Where in the music do you feel shifts in tonality? What about the thematic material that is used? Of course, there are a myriad questions that can be asked.

- Sing or hum ‘anything’ along with the music you hear. Whatever you sing or hum along can vary from being a second voice to just some ‘groaning’, to a ‘rhythmic addition’ to the score. It can be anything, as long as you enjoy doing it.

- Pause a record and ask yourself what tonality, what chord, you hear at that specific spot. Also, after pausing the recording you can take your instrument and play what you just heard or something that ‘freely represents the chord or harmony’ you just heard. Or play something that could follow what you just heard.

2) When listening to ‘music that is not being played’ – listening to music internally - you can:

- Start with the ‘volume button of the inner music on zero and turn it up’. Start with a sensation of a certain energy, emotion or image and listen what sound could come out of that, then 'turning on the volume gradually louder'. Imagine 'being like an aural google earth’, zooming in on a ‘vague’ sound-cloud and explore how you can make melodic lines or harmonies clearer and clearer.

- ‘Borrow a known piece of music from your inner library’ and listen to it in an always ‘curious’ and different way. You can pause internally at certain spots and hear vertically what harmony is sounding on that spot. You can ‘play with the music’ in a variety of ways,turning it from minor to major, diving always deeper into the rhythmic aspect of it, making extreme dynamics in the movement of the phrases.

- ‘Go cross-country’ through your inner ‘style-catalogue’, skipping from one style to another internally. For example, imagine a ‘folk/Bartok-style,‘long-note-recitativo/Gregorian chant’, ‘alla zingarese’, ‘modern/esoteric/contemplative/high, ‘minimal music-ish’, ‘brutal-with a lot of energy and dissonants’, a tango feel, ‘siciliano/berceuse’-feel, a ‘spoken feel’, like ‘speaking-singing’/scatting, a ‘romantic violin melody à la Wieniawsky or Vieuxtemps’. In order to get ideas, you can play internally what you can find ‘in the library’ that is an example of this style.

- Start with a sentence of text. Imagine how it can be spoken in different intonations, rhythms, timing, voices, characters. Listen how this could be transformed to musical phrases

3) Listening to silence is a vast story that dives deeply into psychology, awareness and ways of perception. When you listen to silence, you can:

- Listen to all the sounds that are actually there, but that you were not aware of initially (thinking it was silent)

- Listen to the bits that are in between those sounds, the bits that you do perceive as ‘silent’ and experience how you can ‘sink into’ this silence more and more. Experience what it does to you physically to do so. Observe what emotions it calls to the surface to do so.

- Exercise how you can internally create a sound that comes out of this silence so gradually that it 'does not have a start'. It is a wonderful thing to do, enjoy it. On the other hand, imagine how you could break (literally!) this silence in ‘the most shocking, abrupt’ way.

When ‘working with silence’, it is vital to keep the attention closely connected to the body, to physical experiences and to the breathing. Taking well care that the silence does not grow tension in the body and observing how relaxing more and more within the silence, results in ‘sinking into the silence’ more and more - possibly leading to a vibrating and joyful experience.

10. Jazz-influences on these practice strategies

Over the course of the research there have been encounters with jazz musicians that planted ideas, especially about practicing routines. These ideas did contribute in the development of (at least for me) ‘new’ or different practicing methods.

Suggestions and ideas that came into this research from jazz colleagues:

- If you want to ‘own’ a harmonic scheme thoroughly, the thing to do is to play it through all 12 tonalities. Transposing started to become part of new practising strategies. Pianist David Dolan emphasized that transposing is not about ‘moving everything one note up’ (for example), but it is about ‘sensing the relationships of the harmonies’ – which is ‘knowing the music’ on a deeper level.

- Jazz musicians seem to listen to, ‘drink in’, try to ‘get under the skin’ of the players before them strongly (by listening to recordings). They seem to follow up this listening by transforming what they have taken in with something new from themselves – a mixing of the identity of the ‘model’player or composer with the individual intuition and identity of the ‘learning’ player. This phenomenon is touching, because it results in music being a living language.

- Transcribing (writing out what you hear and by doing so getting in the heart of the music) seems a common thing to do in jazz education. In classical music training it is almost absent. This is understandable, as almost all our repertoire is easily available in print, but that fact makes the print become a rather static thing, ‘written in stone’, ‘coming from the outside to us’, whereas ‘writing out what you hear’ is a way to keep the ‘living quality’ of the music more existent - different people hear differently, add something personal. Transcribing a piece of music makes you know the music much more profoundly.

- 'Playing along recordings’ is something rarely done in classical music – learning from jazz musicians there seems to be on the contrary also a great benefit in playing along recordings. The physical ingredient of taking in what you hear (or: experience) at that moment makes you ‘incorporate’, ‘own’ that personal style of playing in a stronger way.

The observation that many jazz players also compose, is a ‘jealousy-creating’ fact for the classical music scene. Ideally, we would be able to enter the continuum of ‘performing music – improvising music – composing music’ much more – as was the case in classical music until approximately 1850 - and ideally we would also find ways to educate a new generation of classical musicians in that direction.

The following quote from jazz musician Edward Sarath communicates this very clearly6

“Composing and improvising are contrasting yet highly complementary modes of musical expression. Both are capable of standing on their own as rich forms of creativity. Improvisation uniquely enables a kind of real-time, spontaneous invention and interaction that is not possible through the discontinuous temporality of composition, where pieces are melded over a series of creative episodes that may span weeks or months. On the other hand, the very discontinuous temporal framework of composition is uniquely suited to another kind of expressive result – the design of rich formal architectures. As the saxophonist Steve Lace remarked, “there is a music that must be composed, there is another music that can only be improvised” (voetnoot; reference).

Engaging with both processes can greatly enhance the development of musicianship skills. Improvising can generate ideas for composition; composition can provide a kind of structural awareness that feeds back to improvisation, just to mention a few ways these practices can interact. In the earliest days of the European classical tradition, this synergistic relationship between the processes was alive and well as most musicians improvised, composed, as well as performed – which has been the case in jazz since its inception. This complementarity in classical music has sadly become lost in a “division of labor” which has prevailed in that tradition for the past century and half, where the majority of musicians specialize in performance, a distinct minority composes, and improvisation has become almost extinct. From this standpoint, a strong case could be made that jazz is more closely aligned with the artistic legacy of Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, Schubert, and Liszt than the current musicianship paradigm that is confined to performance of these (and other) masters’ works. Happily there are signs that this paradigm is beginning to change, albeit slowly, as more and more classical musicians are beginning to rediscover the gap in their artistic lives created by the absence of these core creative processes”.