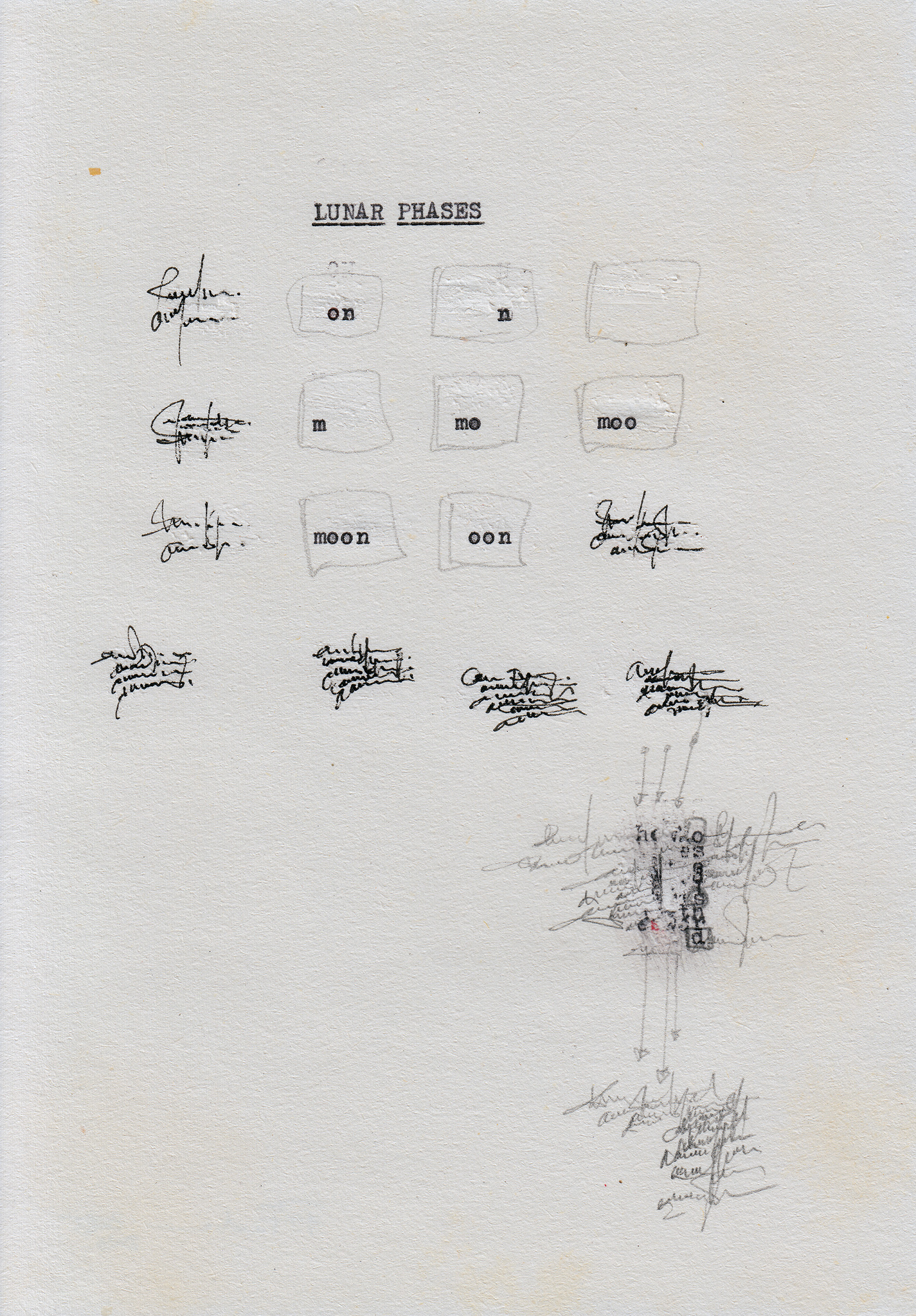

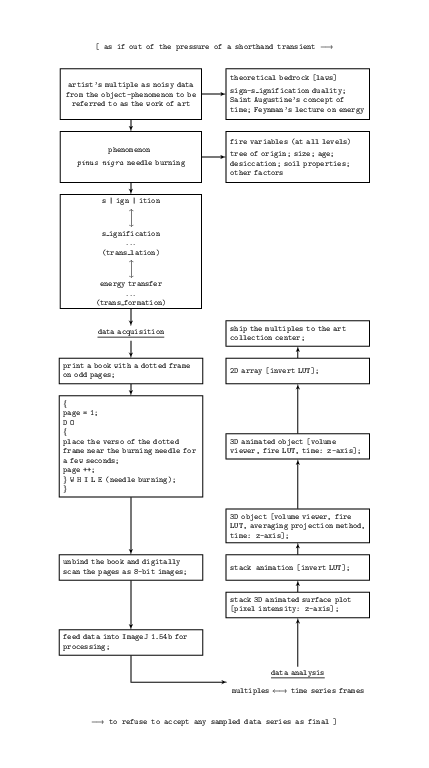

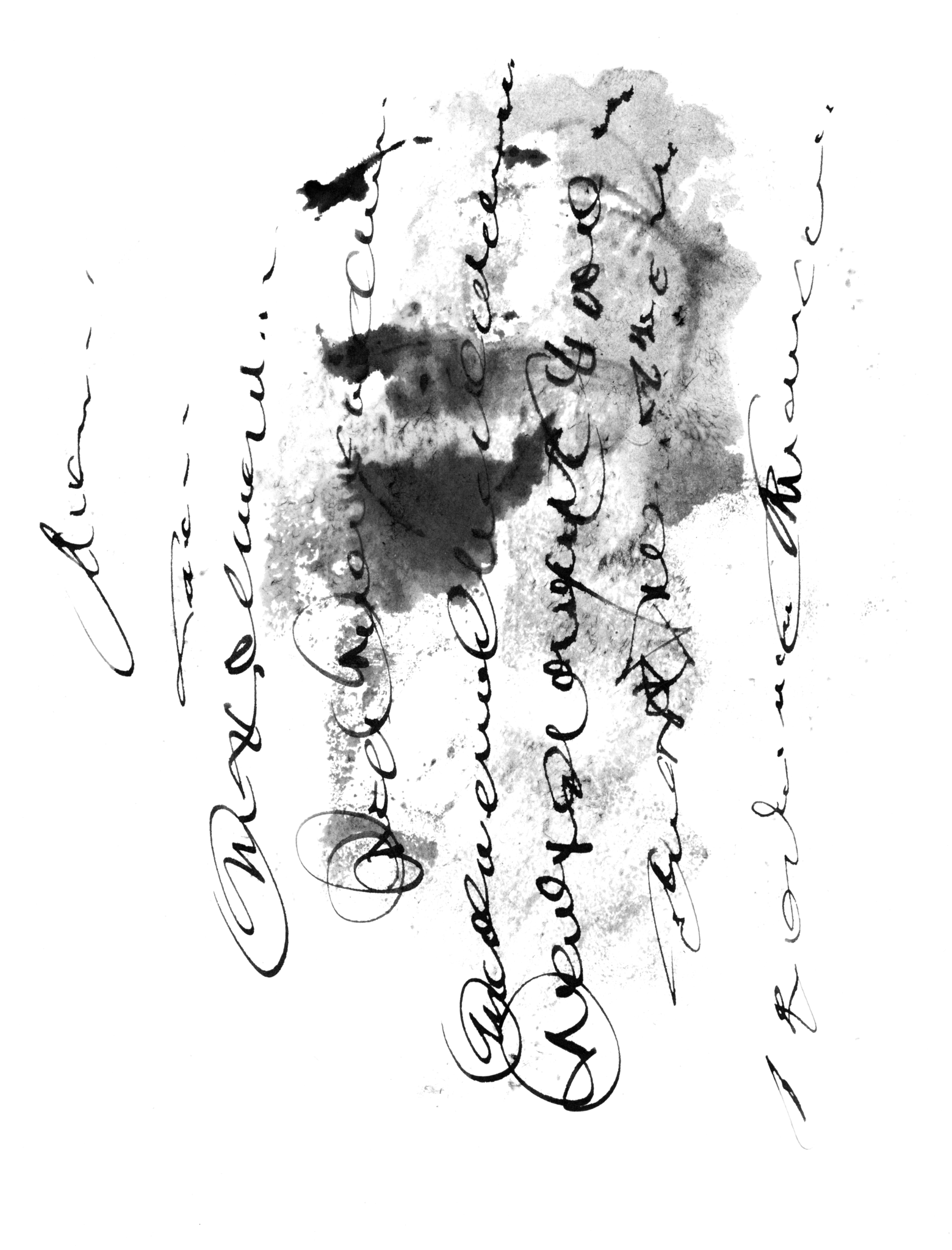

What is energy? If no one asks me, I know; if I wish to explain it to one who asks me, I no longer know. It is, indeed, nothing concrete—only a principle that governs Nature. The universe is a number split up into an endless series of smaller and smaller addends, continuously recombined or reordered according to a complex of interactions. No exception to this law is known. Following the procedure in the caption, the artist is invited to experiment with this principle by collecting energy frames from a burning Pinus nigra needle. Through a series of variations on the flame’s primordial hieroglyph, the material space of writing will be effaced, giving rise to an alphabet of fire. Paper will no longer be the site where the sign resides, but what the sign must breach. Each sign will depend on the angle of the sheet in relation to the flame, which, in turn, is affected by a network of more or less hidden variables intrinsic to the tree (size, age, desiccation, soil properties, etc.). While all of these factors impinge upon the integrity and stability of the alphabet, the amount of energy released during combustion will, to some degree, be stored in—and remain proportional to—the number of sheets used. The fire, split into signs, will establish itself as a thread between what is burning and what is about to burn, between the thought-thing and the one yet to write. The very idea of writing will once again get reified, although no one knows what energy is.

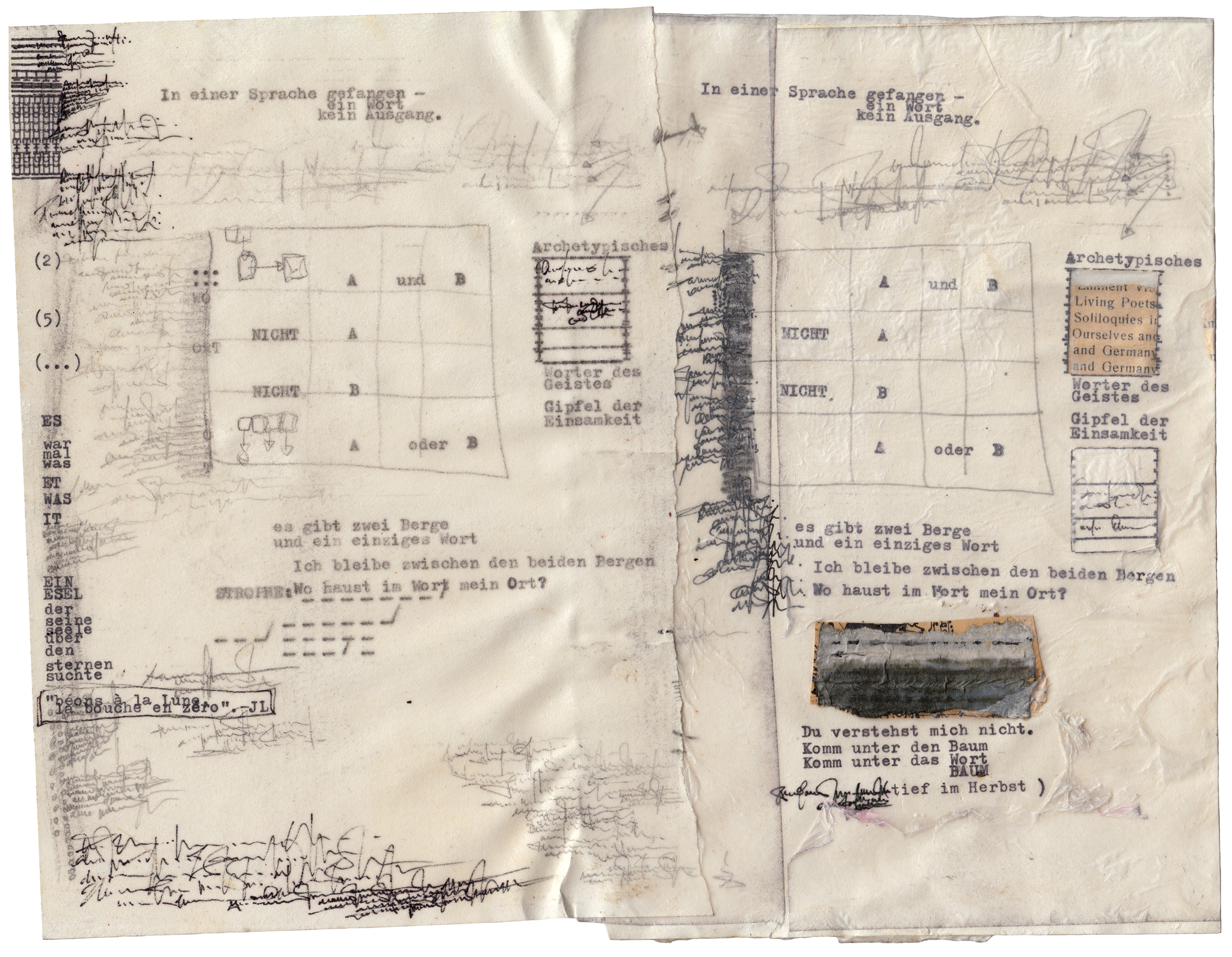

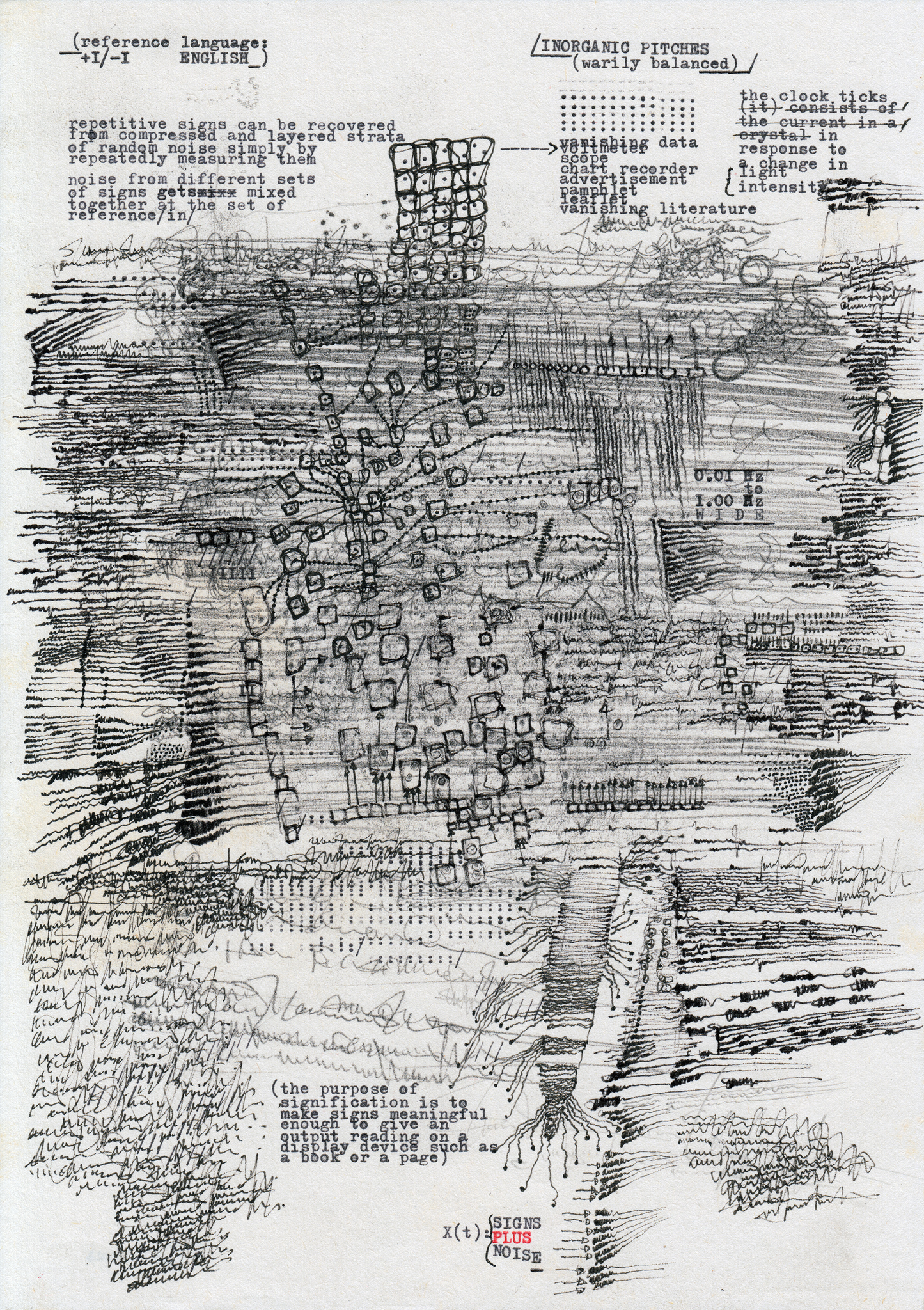

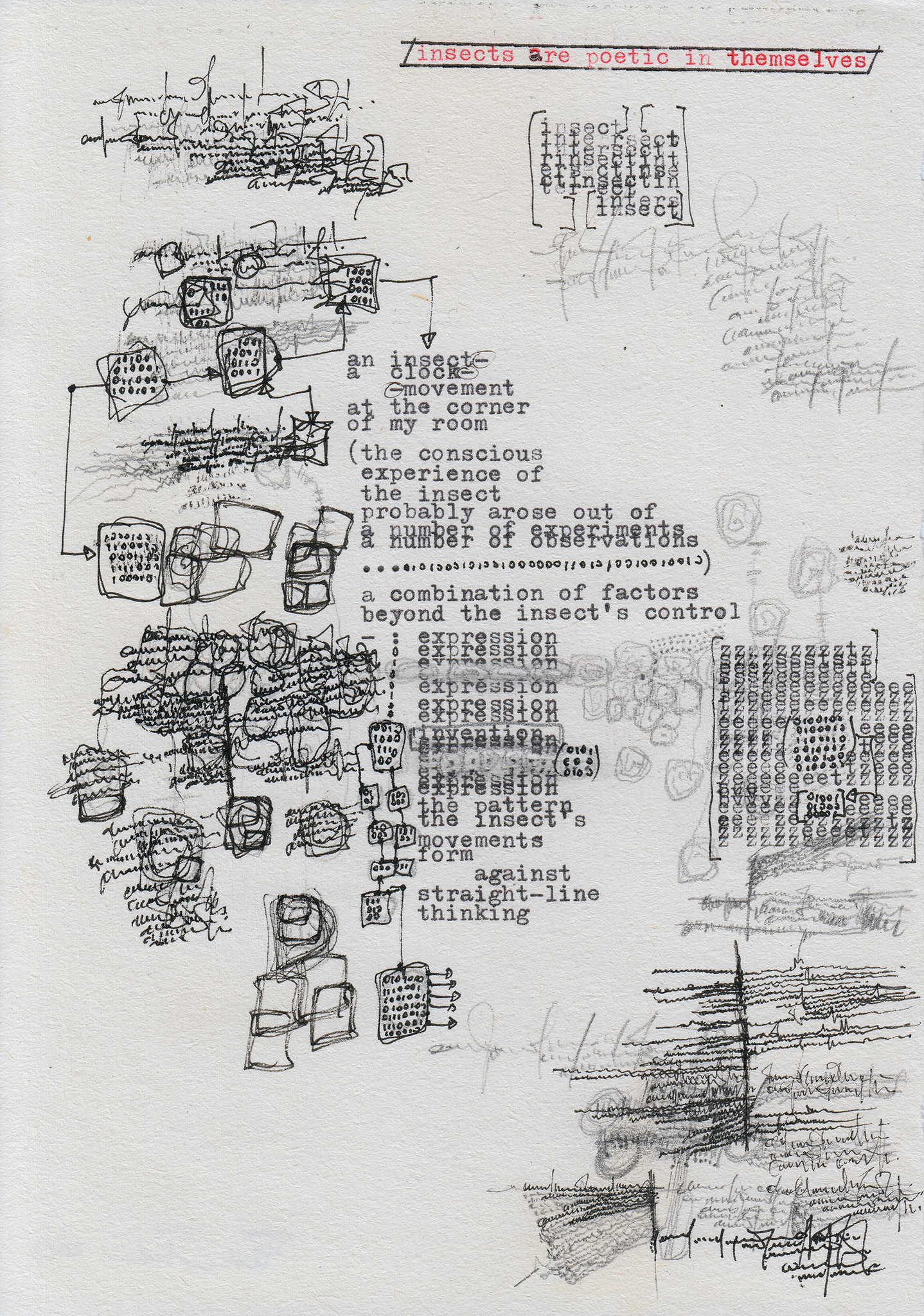

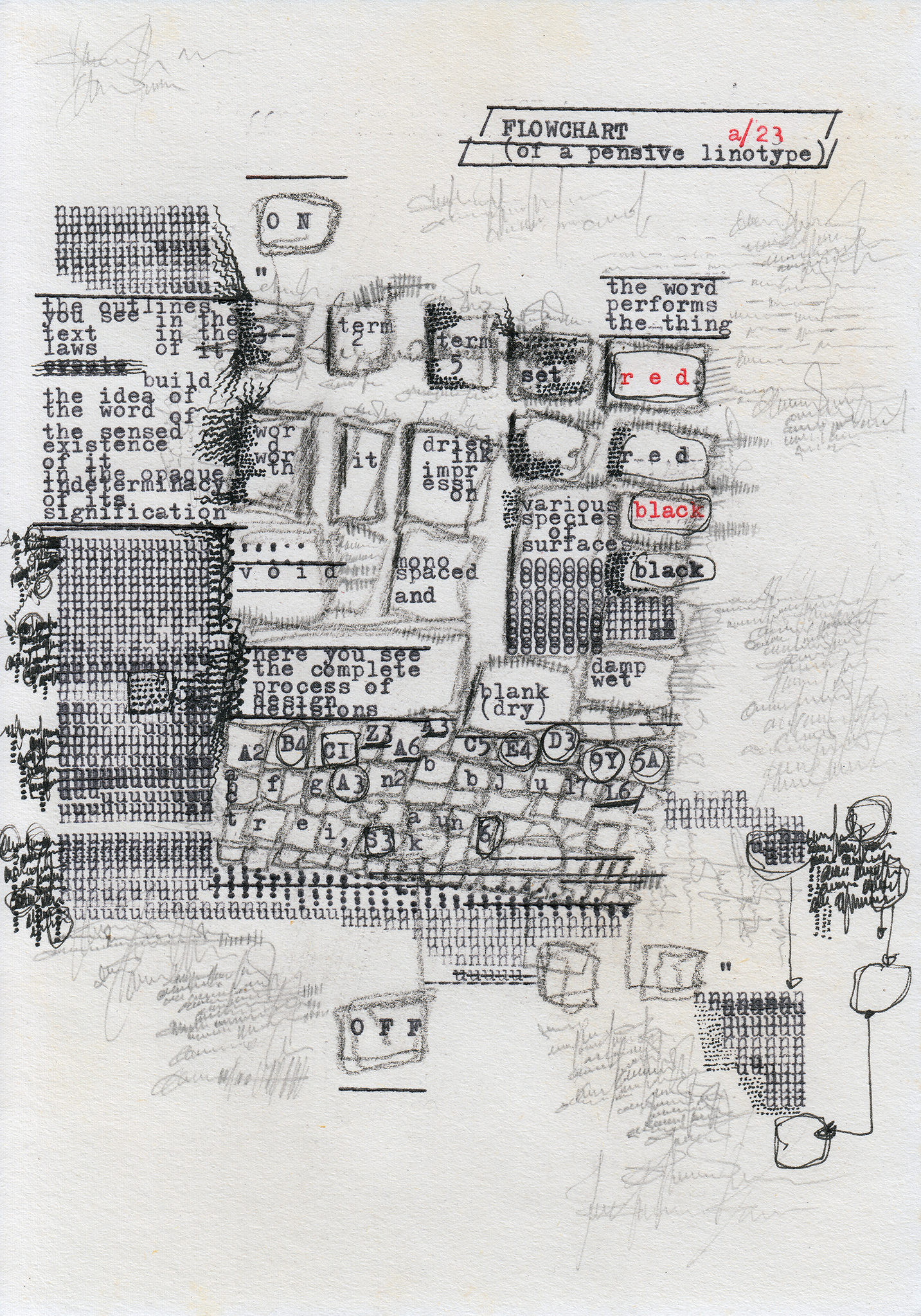

Liner Notes for a Pithecanthropus Erectus Sketchbook | Post-bop

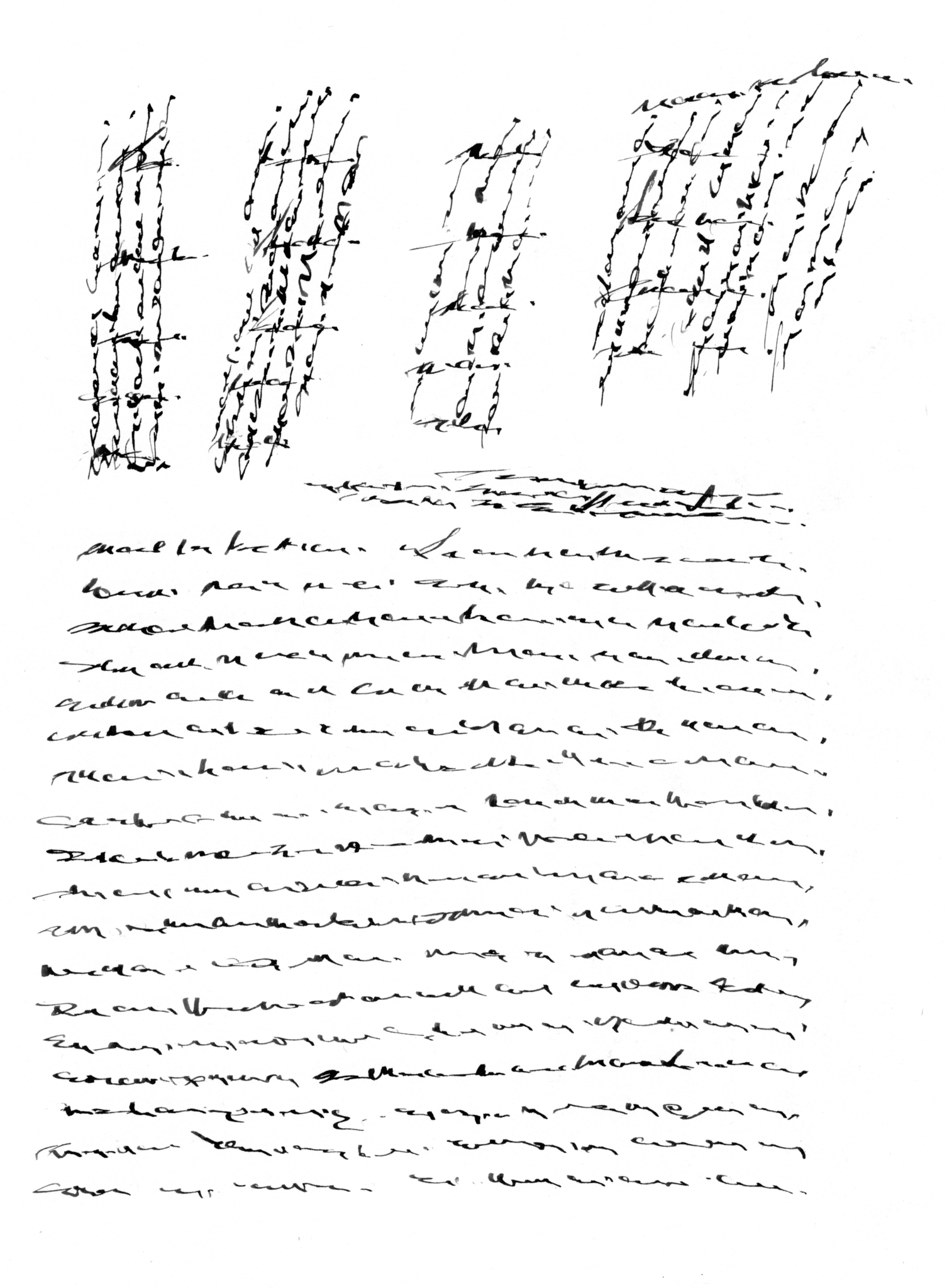

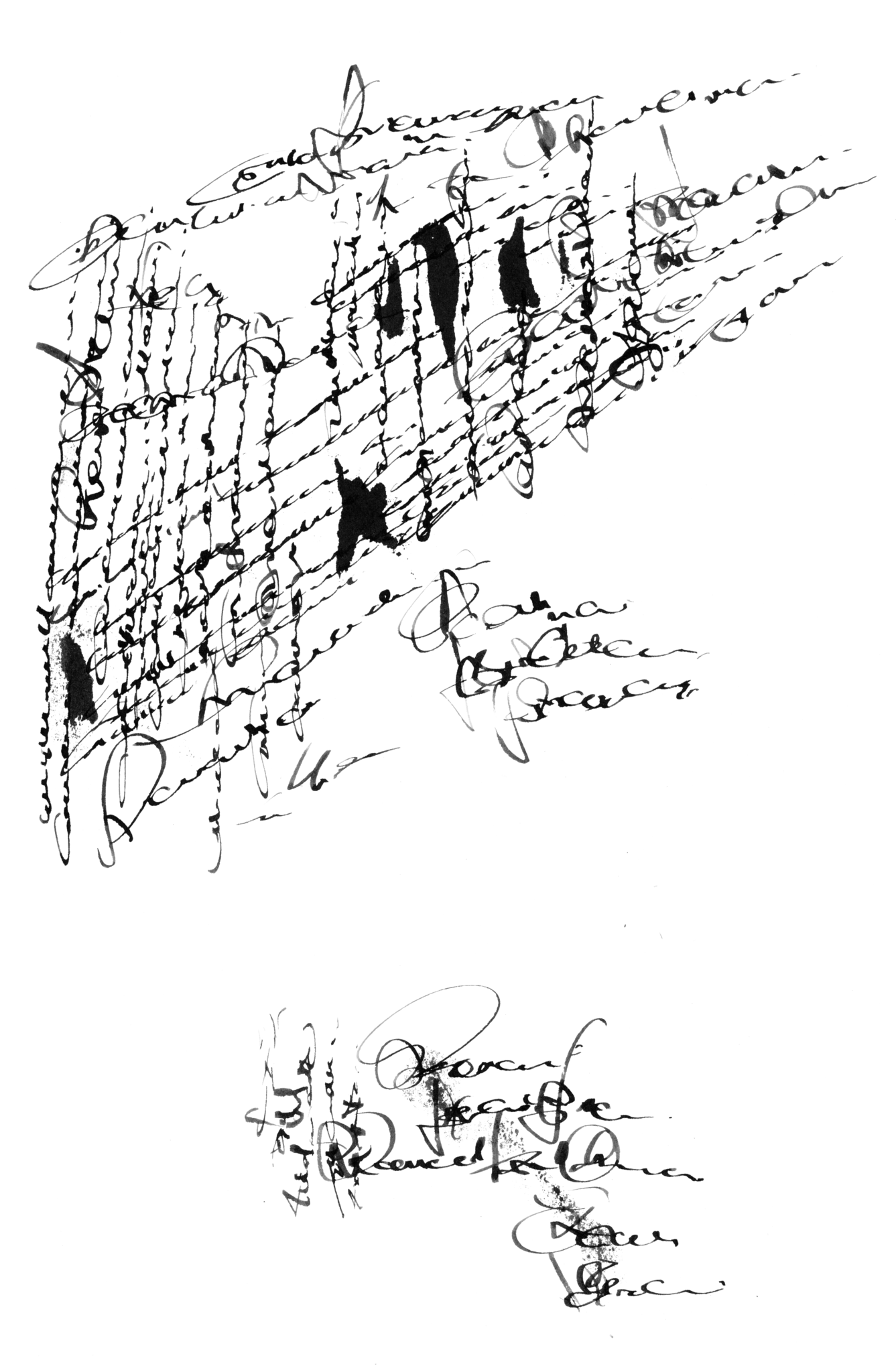

This collection of sheets is a purely asemic tone poem, sketching the mood of the first man to stand erect, taking inspiration from the musically depicted portrait given by Charles Mingus, in his Pithecanthropus Erectus.

Aiming at dealing with the story of mankind in its own way, asemic writing seemed the most appropriate choice, insisting upon semiotics, rather than idioms.

Overcome with his alleged superiority over the trees, likewise standing erect, but unmoving in the background, and over the animals, still in a prone position, man first conceived of conquering the Earth, then of eventually ruling Nature.

Given these assumptions, his sought emancipation led to solitude and self-enslaving.

As the original jazz suite, this poem can be loosely divided into four movements:

evolution, p. 11–23

superiority-complex, p. 24–47

decline, p. 48–53

destruction, p. 54–58

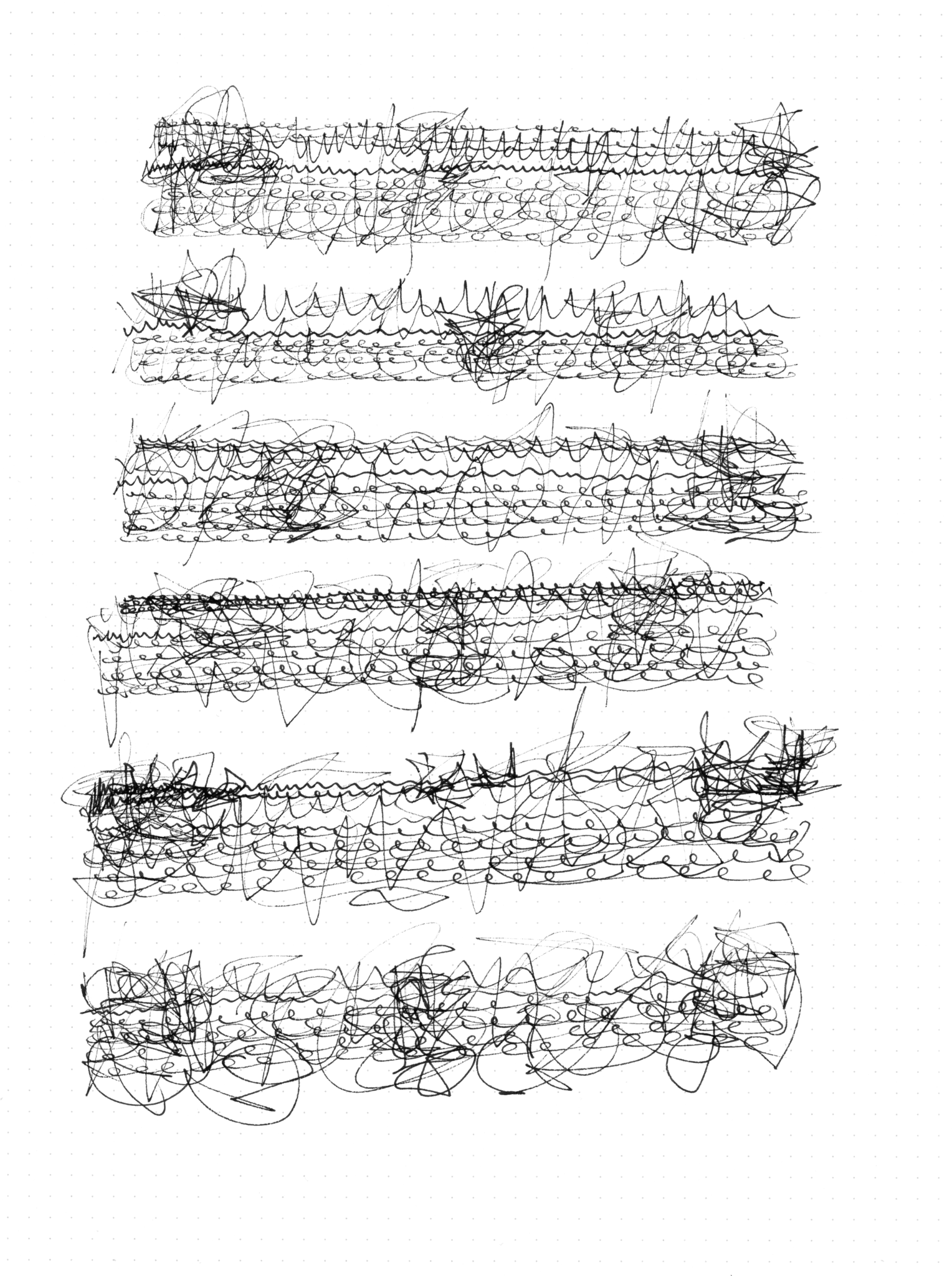

The first movement sets the elementary shapes (dots, stains, lines), which get later on, in the second movement especially, organized into more complex dynamic structures or repeated solos.

The introduction to the third movement, instead, registers a much more organic disturbance in the whole pattern. Further attempts to regain control over that first frantic signs of crisis fail.

The fourth movement is again based on the third, except that it develops into an increasing complexity ending with blank language lines, resembling those on page 28 and 29, but somehow unnaturally upwards, no longer organized into blocks.

The final, definite climax is a white fallout, an unexpressed ultimate (or even anew primordial) act.

London, Coldharbour Lane

Liner notes for a Pithecanthropus Erectus sketchbook, foreword by SJ Fowler, LN 2018, ISBN 979-8640487855 [Asemic-Eng] | buy: amazon | read: archive • watch: YouTube • download: SJ Fowler's review

«Time present and time past

are both perhaps present in time future,

and time future contained in time past»

Burnt Norton, T.S. Eliot

Let us consider this thought experiment.

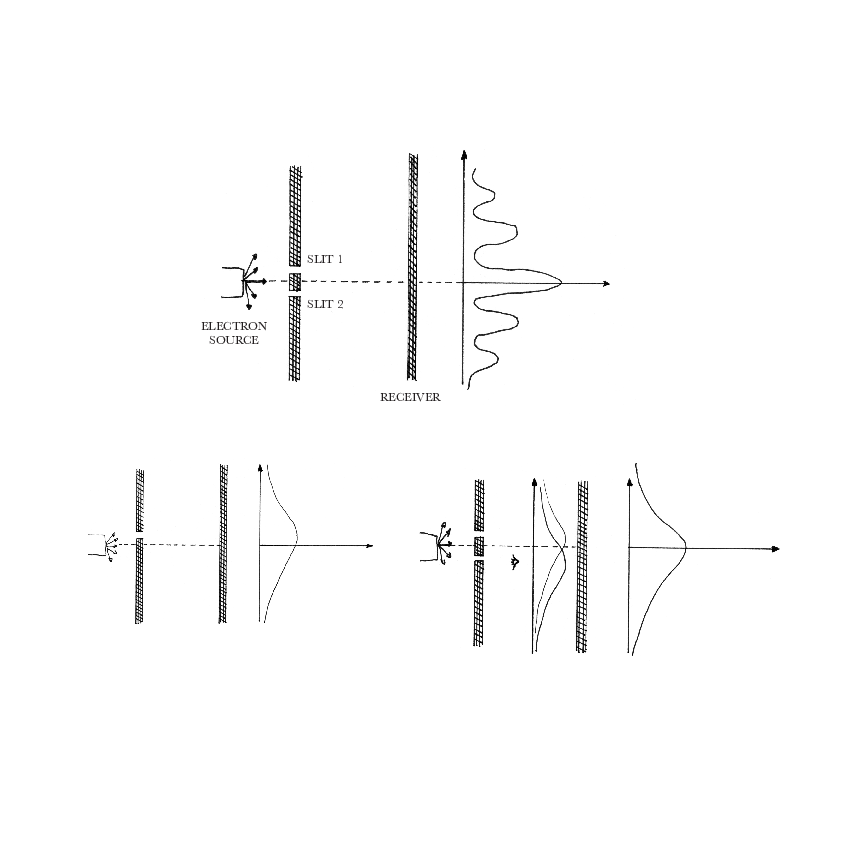

A time source, placed somewhere, generates identical instants, which we assume to be fundamental. In front of it, a plane opaque surface with two fine slits in it, behind which a receiver (time present) serves as a target.

Let us start collecting the hits on the target. The plotted curve depicts the counts.

We can now proceed to answer the question: «How does time point to the target?»

Hypothesis: instants can be divided into two classes: those that have passed through slit 1 (time past) and those that will pass through slit 2 (time future).

Were this assumption true, only those going through slit 1 would have affected the result.

Quite the opposite, both slits appear to be simultaneously open because a certain interference is exhibited: the plot is the same as that of Young’s double-slit experiment with electromagnetic waves.

Time future and time past are both perhaps present in time present.

How does such a phenomenon come about? Do instants travel as if both ways were always open? What complicated paths, back and forth, do they follow?

The passage we don’t take and the passage we take «point to one end, which is always present».

If we were to manage to close slit 2, we would actually get a smooth one-peak curve slightly shifted upward (bottom-left figure). But if we closed slit 1, we would surprisingly get the same smooth one-peak curve shifted downward.

Time future is contained in time present.

And if we peeped into either slit (bottom-right figure), tracking which one each instant goes through, we would observe, for each slit, the same curve as if the other were closed. The two curves would, point by point, add up to an overall smooth one-peak curve, centred right behind the slits.

Do we disturb time around the corner?